WEALTH

SOLUTION

Bringing Structure to

Your Financial Life

THE

Steven Atkinson, Joni Clark, Eric Golberg & Alex Potts

Afterword by DR. HARRY M. MARKOWITZ,

Recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences

WEALTH

SOLUTION

Bringing Structure to

Your Financial Life

THE

Steven Atkinson, Joni Clark, Eric Golberg & Alex Potts

Afterword by DR. HARRY M. MARKOWITZ,

Recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences

Copyright © 2011 Loring Ward

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the

prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain noncommercial

uses permitted by copyright law.

IRN: R 10-239

First edition

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011920405

ISBN: 978-0-615-43722-4

For his friendship, his courage and his passion

for empowering investors through education,

this book is dedicated to the memory of

Gordon Murray.

Foreword

e rst step toward achieving true nancial success is understanding an

important fact: Being rich is not the same as being wealthy. Being rich,

for many, means living an extravagant lifestyle and accumulating all the

latest luxuries that money can buy in the moment. Being wealthy, by

contrast, means setting specic, meaningful goals for yourself and your

family and then making smart nancial decisions to accumulate assets

over time and achieve those key life goals.

is book is about being wealthy.

e authors wrote it to show the steps that many of today’s most successful

families have taken to build, grow and maintain their wealth—and lead

lives that are both highly enjoyable and deeply meaningful. For these

families, the foundation of their success is Structured Wealth Management.

At its core, Structured Wealth Management is an approach to managing

wealth that takes into account the full range of challenges and

opportunities that today’s families face and coordinates their entire

nancial lives so that everything works in concert to solve those challenges

and capture those opportunities. It brings together investment strategies

rooted in proven academic research with methods for addressing the key

investment concerns that today’s families must face.

If you wish to be truly wealthy, Structured Wealth Management is the key

to making that happen. On the pages that follow, you’ll discover the

framework that will empower you to achieve all that is important to you

and your family, along with ways to implement this framework that will

help ensure a lifetime of nancial success.

An entrepreneurial history

How do I know that Structured Wealth Management works? e answer

is simple. Since 2003, I have used it to help clients achieve their most

important goals and dreams. It has become my mission to provide

families the Structured Wealth Management knowledge and tools they

need to determine the very best life that they truly want for themselves

and then help them make it a reality.

My desire to help others make smart decisions about their nances

actually began well before I ever considered becoming a nancial

advisor; it started when I was a young undergraduate student majoring

in engineering. My family never had a lot of money to spare, so to

make ends meet, I took a job at a local pizzeria that I soon learned was

struggling. I helped the owners improve the business substantially—so

much so that they asked me to manage its business model. Once I saw

the economic potential, I realized that I could do much better for myself

by starting up my own pizzeria than I could by continuing down the

engineering path. So, with a trusted partner, that’s exactly what I did.

Our pizzeria venture was a big hit. So big, in fact, that we opened 32

more stores across Ohio during the next six years. As we expanded,

however, I noticed that many of the franchise owners and managers

would approach me with requests to stretch out loan terms, borrow

money, or postpone paying franchise fees. eir need for help always

stemmed from the same thing: a poor nancial decision they had made

that put them in bad shape. Going backward nancially is obviously

bad, but so is spinning your wheels—going to work every day and

failing to increase your net worth isn’t much better. So I began to help

them with their nances to move them and the company in the right

direction. I gured that if I helped them to be proactive with their

money and showed them how to make better decisions, they wouldn’t

end up coming to see me after something had already broken. My help

included everything from business nancials to investing and retirement

planning, funding tax liabilities, securing the correct insurance, and

business succession planning. I didn’t get paid for my advice. I did it

so my people would be protected nancially, be happier, and have good

lives for themselves and their families.

From Wall Street to independence

In the late 1990s, after a short stint in the dot-com world, I decided it

was time to move on and sell my company. Helping people as a nancial

advisor seemed an obvious next step. After going back to school and

earning nancial degrees, I became certied as a nancial planner, got a

job as a stockbroker at a big Wall Street rm and prepared to help people

achieve their nancial dreams.

I was in for a very rude awakening. I learned that Wall Street’s priorities

were not aligned to work in the clients’ best interests. Instead, I was

supposed to sell the clients those products that made the most money

for my employer. It was all about the rm—not the client. It didn’t

matter if it was a 70-year-old trying to preserve wealth or a 40-year-old

trying to aggressively grow wealth—the investment options given to me

by the corporate oce were the same. Why? Because those were the

investments that were most protable for the rm, I remember thinking,

“is is crazy. It’s a hoax!” I couldn’t imagine not doing the right thing

for clients all day long and then coming home to my wife and children

and feeling good. ese clients put their trust in me to be able to provide

what was right for them.

I started looking for another approach—as an independent advisor. I

immediately saw that the independent advisor’s alignment was the

complete opposite of Wall Street’s. As an independent, I would focus

on the client’s needs—the client would be the boss, not the big parent

company with an agenda. My job would be to listen and nd all the best

solutions for each client. Not the best solutions for a parent company,

but the best for the client who is trying to achieve his or her biggest

dreams. I realized that was exactly what I was looking for—and I made

the switch.

Today, I combine an independent approach with the Structured Wealth

Management process to help guide clients with not just their investments,

but also wealth enhancement, wealth protection, tax mitigation, estate

planning, retirement planning and charitable giving. In short, I help

them make smart decisions in all areas of their nancial lives. e need

for this comprehensive approach is vital today. e decisions we make

about our money aect not just ourselves, but also our families, our

communities and the world around us. We all have to be good stewards

of our wealth so that it can do the most good for the people we care

about most. We cannot aord to let these assets wither away due to bad

decision making.

is book will show you how to be that good steward and use your

wealth to build the life you want, which is why I’m extremely honored

to have been asked to write this foreword. I encourage you to read on so

you can learn how I help clients every day to achieve their true nancial

well-being. I wish you success in all your endeavors as you journey down

the road to nancial success.

— J G, CFP®

Acorn Financial Services

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

A Framework for Financial Success ................................................1

Chapter 2

e Key Challenges Facing Today’s Investors ................................7

Chapter 3

e Structured Wealth Management Solution ............................. 15

Chapter 4

e Investment Planning Process: An Overview .........................25

Chapter 5

Markets Work ................................................................................29

Chapter 6

Risk & Return Are Related ...........................................................51

Chapter 7

Diversify with Structure ................................................................ 65

Chapter 8

Building and Implementing Your Investment Portfolio ..............83

Chapter 9

Invest for the Long Term ...............................................................93

Chapter 10

Advanced Planning and Trusted Advisory Relationships..........107

Chapter 11

Putting It All Together ................................................................121

Chapter 12

Selecting the Right Advisor .........................................................129

Afterword .....................................................................................141

About the Authors ........................................................................143

Acknowledgements ...................................................................... 147

Chapter 1

A Framework for Financial Success

“Being rich is having money; being wealthy is having time.”

— H W B

A few years ago, a friend who worked as an executive at a huge

technology rm in Silicon Valley found herself in a dismal nancial

situation — facing an enormous tax bill on stock option gains that,

for a variety of reasons, never found their way to her bottom line.

Suddenly, instead of enjoying a well-earned retirement, replete with

sunny vacations to exotic places and free time to spend with friends

and family — she was forced to continue working for many more

years in order to help rebuild the wealth that she never should have

lost in the rst place.

Her story is troubling and all too common, even for sophisticated,

educated investors. We’ve seen too many similar nancial missteps

over the years. Too many investors never reach their most important

goals — not because they aren’t smart or don’t make the eort, but

because they don’t use a successful plan to help them get there. As a

result, they end up compromising not just their own futures, but the

futures of their families.

Our goal is to give you the tools you need to make smarter nancial

decisions — and avoid the mistakes that too often trip up investors.

We are committed to making sure that investors have everything

they need to achieve all that is important to them and their

loved ones.

Chapter 1: A Framework for Financial Success — 3

If you’re like the vast majority of investors today, you could use such

tools and guidance. Saving and investing to reach your nancial

goals can often seem like a huge challenge. And chances are, you’re

at least a little uncertain about whether the decisions you’re making

with your money in a variety of key areas — from investing for

retirement to minimizing taxes to paying for a child’s college tuition

— are the right decisions.

You are the reason why we’ve written this book. It will give you an

actionable framework to help you make better, wiser, more informed

decisions in all areas of your nancial life.

To get started, we need to acknowledge an important fact. It’s become

harder than ever to navigate through the increasing complexity of our

nancial lives and ensure that we are making consistently smart moves

with our money. Achieving major nancial goals was challenging

enough even before the so-called “Great Recession” and the tremendous

upheaval in the nancial markets in recent years. In the wake of those

historic events, many investors feel more confused and uncertain about

their futures and how to get back on the right track.

When we rst sat down together to discuss the idea of writing a

book to help investors, it was in late December 2009 — the tail

end of a decade that saw the worst 10-year return for the Dow

Jones Industrial Average since the 1930s. During that time, many

investors watched their hard-earned savings plummet in value.

Many questioned their approach to saving, spending and investing,

and worried that they would have to delay or forgo some of their key

life objectives such as a comfortable retirement, or leaving a legacy

to their children. is fear that many investors experienced during

the worst of the recent downturn is not easily forgotten — and has

left many wondering how to get back on track and stay there over

the long run.

2 — The Wealth Solution

But if that’s the reality today, it’s important to recognize another

fact: ere is a process that can enable you to cut through all the

confusion and noise, simplify your nancial life and help ensure

that you’re making the smartest possible decisions about your

money consistently — day in and day out. What’s more, it’s a

prudent, time-tested process based on empirical evidence about how

the nancial markets operate, a process used by some of the most

successful families in America to manage their wealth.

is process — called Structured Wealth Management — is what this

book is all about. As you’ll discover, Structured Wealth Management

is a fundamentally dierent method for managing your nancial life

from those used by other investors (including most nancial advisors

and investment professionals). It is designed to help you solve

your biggest nancial issues — including investments, taxes, estate

planning, wealth preservation and protection, and charitable giving.

Structured Wealth Management: An Overview

Structured Wealth Management is a dened and disciplined process

that consists of a number of closely connected steps. We’ll explore

this process in greater detail in the following chapters. For now, it’s

helpful to understand three main characteristics:

• Structured Wealth Management is consultative. Structured Wealth

Management helps you identify and clarify the specic nancial

goals that are truly important to you — those that hold the most

meaning and will have the greatest impact for you and your

loved ones. By beginning with this step, all your future nancial

decisions can be made “with a purpose” — that is, within the

context of your key objectives. is method is distinctly dierent

from other approaches, in that it steers you to make decisions based

not on events in the markets or the economy but on the steps you

should take to further your progress toward your unique goals.

Chapter 1: A Framework for Financial Success — 3

2 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 1: A Framework for Financial Success — 5

Wealth management should not be concerned with picking

hot stocks or trying to beat the overall market. Instead, wealth

management blocks out the “noise” by encouraging investors to

answer an extremely powerful question: What should I be doing

with my money to provide the life I want most?

is approach to wealth management tangibly puts tremendous purpose

behind your nancial decisions. Your timeframe and perspective are

immeasurably broadened, and you no longer have to worry about what

the stock market is doing today or this month or even this year. You are

no longer thinking tactically, but strategically. Your plan is based around

a desired long-term outcome — not on beating the market or simply

guarding your wealth from short-term losses.

• Structured Wealth Management is comprehensive. Many

investors focus only on one aspect of their nancial lives — often

their investment portfolios or 401(k) accounts. Of course, smart

investment choices are crucial to achieving long-term nancial

goals such as a secure retirement. But for nearly all of us, there are

other vital issues that need to be addressed to make our goals come

to fruition. Depending on your circumstances, these needs could

range from saving for future college tuition costs to helping aging

parents meet health care needs to providing for children and heirs

to supporting your favorite non-prot organizations and causes.

Unlike many approaches to nancial planning, wealth management

addresses the full range of nancial-related issues that investors and

their families face. What’s more, it ties all those various pieces and

moving parts together seamlessly, so that the components of your

nancial life — investments, insurance, wills and trusts and so on

— always work together as eectively as possible to achieve the

meaningful goals you’ve set.

4 — The Wealth Solution

• Structured Wealth Management is rooted in facts, data and analysis.

Based on decades of nancial data and research, this rational and

practical approach helps investors avoid making rash, emotional

decisions that could derail their plans and make it harder for them

to reach their goals. For example, many investors in the wake of

the nancial crisis of 2008 and 2009 became fearful of investing in

the nancial markets. But we know from history that markets have

tended to work in the long run — despite the occasional crisis.

In order to fully take advantage of Structured Wealth Management

and make the most of its benets, we encourage you to work in

partnership with a nancial advisor who uses the type of approach

we outline in this book.

e reason is simple: Successfully managing all the key aspects of your

nancial life is a complex process — one that can require a great deal

of time and attention to detail to get right. In our experience, we’ve

seen that most investors lack the time, knowledge or desire needed

to manage their wealth. As a result, we have found that investors

tend to end up in much stronger nancial shape when they enlist

a professional whose job is to stay acutely focused on their clients’

nancial lives and the Structured Wealth Management process at all

times. is is not to say that it is impossible to implement Structured

Wealth Management on your own and have a better nancial life.

But this process will be so time consuming and requires such extensive

knowledge and specialization, it is not very practical for the majority

of investors. We believe it makes sense for your wealth management

eorts to be as successful as they possibly can — and that working

in partnership with the right kind of nancial advisor oers a much

surer and smoother path to achieving your nancial goals.

Chapter 1: A Framework for Financial Success — 5

4 — The Wealth Solution

Why You Need Structured Wealth Management

e term “wealth management” may seem a little o-putting if you

don’t think of yourself as particularly wealthy. e truth is, you don’t

have to be among the super-rich to make the wealth management

process a successful and important part of your nancial life. Quite

the contrary. We all face numerous nancial goals, challenges and

choices, from paying for today’s bills to funding goals that might be

decades away to leaving a lasting legacy. ese concerns won’t solve

themselves or go away if you ignore them. Indeed, by disregarding

them, you’re simply asking for someone else to make the decisions

about how and where your money is used.

If you don’t want to be dependent on or beholden to others,

you need to eectively manage the money you do have. Wealth

management’s aim is to help you make smart, rational choices about

your nances so that you can control your own destiny and build

the life you want for yourself and your family. is approach makes

wealth management entirely applicable to your life — regardless of

whether you have $100,000 or $20 million. It is designed to help

address issues that almost all of us will have to face at some point in

our lives. So ask yourself: Do you want to create a plan to address

those issues structurally, or do you want to leave it all to chance?

We think the answer is obvious. You have an obligation to make

wise choices about your wealth and do all you can to avoid frittering

it away. e reason: Your wealth can create a world of good — for

yourself, your spouse, your children, grandchildren, and beyond. So

whether or not you “feel” wealthy isn’t the point. In the end, your

assets can be a tremendously positive force in many, many lives. But

you have to take proper care of them to make all that happen.

We’d like to show you how.

6 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 2

e Key Challenges Facing

Today’s Investors

To understand how Structured Wealth Management may help you achieve

nancial success, it’s necessary to rst recognize the most signicant issues

aecting investors today.

Chances are you’re nding it more challenging than ever these days to

wrap your arms around your increasingly complex nancial life and

make good sense of the entire picture. But the sooner you determine

where you are now and where you want to be in the future, the sooner

you can set out to build a plan that tackles the major issues that impact

your life.

For more than two decades, we have worked closely with hundreds

of top nancial advisors who together serve thousands of investors.

Our experience helping advisors help their clients achieve their most

important nancial goals has taught us that investors today share six

major concerns:

Concern 1: Preserving Wealth in Retirement

How are you going to grow and preserve your wealth so that you have

the money required to meet your needs and fulll your goals — not just

today, but for decades to come?

It’s a huge question — one that investors are asking themselves more

and more. e vast majority, regardless of their level of wealth, are

concerned about preserving their wealth so they will have enough

money throughout retirement.

6 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 2: The Key Challenges Facing Today’s Investors — 9

is makes perfect sense. Few of us want to be forced to downsize our

lifestyles. And yet, many investors are not nancially positioned to max-

imize their chances of maintaining their lifestyles during retirement —

especially when you consider the challenges that today’s pre-retirees and

retirees must contend with. For example:

• Ination’s impact. Rising prices can decimate your purchasing

power, savings and your ability to preserve wealth throughout your

golden years. Assuming the long-term historical annual ination rate

of around 3%, an annual xed income of $100,000 would be worth

just $86,000 in ve years and only about $40,000 in 30 years. e

same purchase that would cost $100,000 today would soar to more

than $240,000 in 30 years. And if ination runs at a much higher

rate than normal for an extended period — a real concern given the

huge amount of government spending that has occurred in recent

years — the goal of wealth preservation and income replacement

throughout retirement could become even tougher to achieve.

• Rising life expectancies. anks to continued advances in health

care, American seniors are living 50 percent longer than they were in

the 1930s. According to the Centers for Disease Control, a 65-year-

old can now expect to live another 18 years, on average.

1

For a 65-year-

old married couple, there’s a 58% chance that one of them will live to

90 and a 29% chance that one will reach 95.

2

While that is certainly

good news, it also means that you must make your money last much

longer or risk running out of money before you die.

• Soaring health care costs. e cost of health care has been rising at

a much faster pace than the overall rate of ination in recent years. is

should be of particular concern to aging investors who are more likely

than younger Americans to consume substantial amounts of health care

goods and services. What’s more, Medicare might only cover about

50% of a typical retiree’s medical expenses. Consider that seniors age 65

and over spend an average of $4,888 per person annually for deductibles,

copayments, premiums and other health care costs not covered by

insurance, according to the most recent National Health Expenditure

Survey.

3

at amount is more than two times the amount spent by

8 — The Wealth Solution

average non-elderly adults. And the largest expenditures occurred

among those 85 and older. According to the Employee Benet

Research Institute (EBRI), a retired couple age 65 would need

approximately $338,000 to have a 90% chance of covering their

out-of-pocket health care expenses in retirement.

4

• A weakened Social Security system. It’s no secret that Social

Security has long been in trouble, but a look at the numbers is

particularly sobering. Under current assumptions, Social Security

trust fund expenses are expected to exceed income from taxes some

time around 2016. By 2024, those expenses are expected to exceed

income from taxes plus interest income, and the trust fund is

expected to be exhausted by 2037, according to EBRI.

5

• e diminished role of pensions. Retirement has become a largely

self-funded venture, as evidenced by the fact that just 32% of

workers today participate in some type of dened benet (pension)

plan. at’s down from a full 84% in 1980, according to EBRI.

ese days, the majority of workers (55%) participate in dened

contribution plans — 401(k)s and the like.

6

• Taking care of kids and parents. According to the Pew Research

Center, one out of every eight Americans, ages 40 to 60, is raising

a child while also caring for at least one aged parent at home. In

addition, roughly 7 to 10 million Americans are caring for their

aging parents from a long distance away.

7

_________________________

1 Center for Disease Control and Prevention, “National Vital Statistics Reports,” Vol. 56, No.

10, 2008

2 American Academy of Actuaries, 2008.

3 “National Health Expenditure Data: Personal Health Care Spending by Age Group and

Source Of Payment, Calendar Year 2004,” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

4 “Savings Needed for Health Expenses in Retirement: An Examination of Persons Ages 55

and 65 in 2009,” June 2009, Vol. 30, No. 6, Employee Benefit Research Institute, 2009

5 “The Basics of Social Security Updated with the 2009 Board of Trustees Report,” July 2009,

Employee Benefit Research Institute

6 EBRI Databook on Employee Benefits, updated April 2010, Employee Benefits Research Institute

7 “From The Age of Aquarius to the Age of Responsibility,” Pew Research Center, 2005.

Chapter 2: The Key Challenges Facing Today’s Investors — 9

8 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 2: The Key Challenges Facing Today’s Investors — 11

e end result: Too many investors saving for retirement today face a

higher level of uncertainty about their future prospects than their parents

and grandparents did. In the wake of that uncertainty, you simply have

to be smarter, plan better and question many of the assumptions long-

held by previous generations and many in the nancial services industry.

We believe that traditional “rules of thumb” advice such as needing 70%

of your working income during retirement cannot be taken as gospel

anymore. Your retirement plan needs to reect the realities of the world

today and going forward. In chapters ve through nine, we will explore

how you can position your portfolio to capture the growth and

profits that the nancial markets generate, while minimizing downside

risk through proper portfolio allocation and ongoing risk maintenance

and rebalancing.

Concern 2: Minimizing Taxes

You’ve probably heard the adage that “it’s not what you make, it’s what

you keep that counts.” Not surprisingly, mitigating income taxes is a

major concern for most investors. No one enjoys paying taxes and in-

come taxes are typically the most obvious and onerous taxes investors

face. In addition, mitigating estate taxes and capital gains taxes also

ranks high on the list of many investors’ concerns.

Such concerns are well founded, as taxes can signicantly erode your ability

to grow and preserve wealth. From 1926 through 2009, for example,

stocks as represented by the S&P 500 Index, gained 9.8% annually.

After taxes, however, that return fell to just 7.7%. Bonds’ 5.4% annual

return dropped to a mere 3.4% once taxes were taken into account.

In real terms, a $1 investment in stocks back in 1926 would have grown,

before taxes, to $2,592 at the end of 2009 — but just $510 on an after-

tax basis.

8

ere’s cause for additional concern. Taxes during the past decade or

so have been hovering at relatively low levels — but may be set to rise.

Trying to predict tax code changes is a risky bet, of course. But you

need to be aware that higher taxes across the board could be on their

way — and at the very least, build exibility into your plan so you can

10 — The Wealth Solution

make adjustments should your tax situation change. e good news:

You can take steps to minimize the taxes you pay and keep more of what

is yours by using a variety of wealth management techniques, such as

tax ecient investment vehicles and smart asset location strategies that

will be explored later.

Concern 3: Eective Estate and Gift Transfer

e ancient Chinese adage that “wealth never survives three generations”

seems equally applicable today. A major concern for many investors is

ensuring that their heirs, parents, children and grandchildren are well

provided for in accordance with their wishes. And yet, our experience

is that most investors don’t have an estate plan — and many of those

who do, have outdated plans. Even more troubling: 65% of all American

adults don’t even have a will, according to a 2009 Harris Interactive study.

9

Many investors don’t take the appropriate actions in this key area of

their nancial lives because they assume they don’t possess enough

wealth to necessitate an estate plan. Regardless of your net worth, the

ability to ensure that your assets go to where you want them to has

numerous and important potential implications — from being able to

help a child or grandchild go to college to ensuring the continuity of a

family-owned business to simply avoiding probate. Take college tuition,

for example. College education expenses have risen at a rate of more than

5% annually during the past decade, according to the College Board.

10

at means a child born today could need over $220,000 to attend a

four-year public college in 2028 — more than triple today’s college costs.

Passing on wealth and using it to benet your heirs as you see t doesn’t

happen automatically — it requires the implementation of the right

strategies for your goals and situation. As you’ll see later, those strategies

might include everything from correct titling of assets to smart gifting

strategies and trusts designed to provide maximum benets to a spouse,

family members or charities.

_________________________

8 Morningstar, Inc. 2010

9 www.lawyers.com/understand-your-legal-issue/press-room/2010-Will-Survey-Press-Release.html

10 “Trends in College Pricing 2009,” The College Board

Chapter 2: The Key Challenges Facing Today’s Investors — 11

10 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 2: The Key Challenges Facing Today’s Investors — 13

Concern 4: Wealth and Income Protection

A signicant number of investors today are worried about keeping

wealth safe from potential creditors, litigants, children’s spouses and

potential ex-spouses, as well as from catastrophic loss. ey also want to

be sure that their loved ones are protected in the wake of major health

problems or other unforeseen events. Certainly many professionals

(such as attorneys and physicians), business owners and entrepreneurs

need to focus on protecting their hard-earned wealth. And in today’s

highly litigious culture, nearly everyone needs to consider the possibility

of having their wealth unjustly taken from them. Increasingly, investors

are realizing the importance of confronting some tough and potentially

uncomfortable questions:

• WhatwouldhappenifIwasthevictimofafrivolouslawsuit?

• Whatwouldhappenifoneofmychildrenmarrieda“golddigger,”

then divorced and was sued for a large sum?

• Whatwouldhappenifoneofmychildrenwasinanaccidentinmy

car or someone suered an injury in my home?

• Whatifamajordisabilitypreventedmefromworkingandgenerat-

ing an income for my family?

• WhatifIendupneedingtoliveinanursinghomeorrequirehome

health care services?

Wealth management strategies aimed at wealth protection can motivate

creditors to settle, mitigate the possibility of being sued or minimize the

nancial impact of a judgment. Various trusts and business structures

can work eectively in this area. Trusts and insurance can also play a role

in protecting your wealth and income from an unexpected hardship.

We’ll examine some of these strategies in Chapter 10.

Concern 5: Charitable Gifting

Helping to facilitate and increase the eectiveness of their charitable

intentions is also very important to many investors. From direct gifts

to formal gifting structures like donor advised funds and private family

foundations, many investors are looking to ensure that their money is

12 — The Wealth Solution

being used by their chosen charities to generate the maximum impact

on the social and economic issues they care about most.

Simultaneously, these investors want to make sure that their philan-

thropic goals don’t conict with or endanger their own nancial futures

and their ability to secure a comfortable retirement for themselves and

leave a legacy for their families.

Concern 6: Finding High-Quality Financial Advice

Many investors have long been concerned about working with capable

nancial professionals. It’s little wonder. For decades, much of the nancial

services industry has been driven by a sales-oriented culture that stressed

pushing products instead of providing comprehensive wealth manage-

ment services.

is concern reached a peak during the market downturn of 2008 and

2009 fueled by enormous market volatility, the revelation of the largest

Ponzi scheme in history, and the fact that the largest investment rms in

the world suered tremendous losses from bad investment decisions they

made on their own behalf. All of this created a signicant and still-grow-

ing sense of dissatisfaction in and distrust of the nancial services industry

among many investors. Consider the following from a 2008 Survey:

• 81percentofinvestorssaidthattheyplannedtotakemoneyaway

from their current advisor.

• 86percentofinvestorsplannedtotellotherinvestorstoavoidtheir

advisor.

• Amere2percentplannedtorecommendtheiradvisortootherinvestors.

11

We recognize that many of you are looking for guidance and assistance

in managing your nancial life. With that in mind, we’ve included a

chapter in this book to help you nd professionals who oer objective

advice and who would act as a true duciary on your behalf. e good

news is that during the past decade or so, more and more advisors have

begun implementing a true wealth management process and acting as

_________________________

11 Prince and Associates, 2008

Chapter 2: The Key Challenges Facing Today’s Investors — 13

12 — The Wealth Solution

duciaries to their clients. If you choose to work with an advisor, you

may nd great benet in using the guidelines and best practices in

this book.

You most likely share at least some or possibly all of the aforementioned

nancial concerns. Each one is a sizable challenge on its own — and

taken together, they present you with a potentially enormous hurdle on

your path to a comfortable, secure and meaningful nancial life. is

is where the wealth management process brings tremendous value. By

helping you develop integrated solutions to these concerns and creating

a plan that strikes the optimal balance between them, you can simplify

your nancial picture and achieve greater overall nancial success than

you could by dealing with these challenges on a case-by-case basis.

14 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 3

e Structured Wealth

Management Solution

As you’ve seen, the nancial challenges you face may be sizable and

complex — and they can aect every facet of your life. To address them,

you need a disciplined process that will allow you to consistently make

the prudent decisions that will help you achieve your most important

goals. Without this approach, you may needlessly put your future and

your family’s future at risk.

We believe that the most eective way for most investors to address the

many challenges they face is by adopting a comprehensive Structured

Wealth Management process. Indeed, that’s exactly what many of today’s

most successful families are doing.

But what exactly do we mean by comprehensive Structured Wealth

Management? e term “wealth management” has become a buzzword

in recent years. Financial advisors of all types are now calling themselves

“wealth managers” and claiming to oer wealth management services.

Unfortunately, many of these advisors are wealth managers in name only

— after all, the title “wealth manager” sounds much more impressive

than “stockbroker.”

We believe that wealth management is not a term open to interpretation

or multiple denitions. In order to benet from true wealth

management, you need to make sure you’re actually bringing together

wealth management professionals who possess the capabilities and

expertise to address your biggest nancial challenges and goals.

14 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 3: The

Structured Wealth Management Solution

— 17

16 — The Wealth Solution

Structured Wealth Management Dened

At its core, Structured Wealth Management encompasses each specic area

of your nancial life (i.e. tax planning, estate planning, risk management,

etc.) employing professionals who have expertise in these specic areas.

e wealth management process stands in stark contrast to how most

investors operate today. e vast majority of investors tend to address

nancial goals like college and estate planning on an ad hoc basis — treating

these issues as separate concerns. ese investors neglect to understand

that the complex scope of issues they face are often deeply interconnected

and must be managed in a coordinated manner. Usually, issues are dealt

with only as they arise, and typically just enough information is gathered

to implement the particular solution to the problem at hand.

Structured Wealth Management should be thought of as a detailed

blueprint guiding all your decisions, ensuring that they all work together

in a coordinated manner.

Structured Wealth Management accomplishes this in three ways:

1. Using a consultative process to gain a detailed understanding of

your deepest values and goals. is process helps ensure that your

wealth is utilized to pursue your key life objectives.

2. Employing customized solutions designed to t your specic needs

and goals beyond simply investments. e range of services and

tools involved in crafting wealth management solutions might include

insurance, estate planning, business planning and retirement planning.

3. Delivering these customized solutions in close consultation with

other professional advisors. is enables investors to work closely

— and in a coordinated manner — with trusted advisors to identify

potential issues, implement solutions and regularly monitor your

overall nancial situation. Such advisors oer valuable expertise,

perspectives and analysis that can help investors avoid making

irrational decisions that jeopardize their nancial goals.

Broadly, this process incorporates all the main components of wealth

management:

• Investment planning allocates your assets based on goals, return

objectives, time horizons and risk tolerance and is the foundation

upon which a comprehensive wealth management solution is created.

• Advanced planning addresses the entire range of nancial needs

beyond investments in four primary areas: wealth enhancement,

wealth transfer, wealth protection and charitable gifting.

• Trusted advisory relationships are created by assembling and managing

a network of experts who will be involved in providing solutions to a

variety of nancial issues where they have specialized expertise.

To organize your thinking and approach to wealth management, you

can use this formula:

Structured Wealth Management = investment planning +

advanced planning + trusted advisory relationships

Investors rarely take this type of coordinated and comprehensive approach

with their nances. is can lead to problems that may jeopardize the

nancial health of their families, their businesses and themselves. is is

why wealth management is so important: It enables you to see the big

picture at all times and make decisions within this framework instead of

focusing on only one aspect.

Incorporating a Structured Wealth Management approach requires

you to think through the full range of the nancial challenges you

and your family face, and develop optimal solutions that work in a

coordinated manner. Whether you act as your own wealth manager or

work collaboratively with a professional wealth advisor, you will gain a

tremendous advantage over other investors who take a less disciplined,

ad hoc approach to managing their nancial lives.

Chapter 3: The

Structured Wealth Management Solution

— 17

16 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 3: The

Structured Wealth Management Solution

— 19

18 — The Wealth Solution

e Wealth Management Consultative Process

e Wealth Management Consultative Process is a formal series of ve

structured steps, which are typically conducted as meetings:

1. e Discovery Meeting. is rst step is to help you uncover and

clearly identify your true nancial goals — the things you want and

need most out of life. e overarching goal of the Discovery Meeting

is to understand your unique situation — your key goals and values

— and identify the challenges you face in achieving what is most

important to you. Once these goals are established and understood,

your optimal plan can be designed.

2. e Investment Plan Meeting. At this meeting, the wealth manager

presents a detailed series of investment recommendations designed

around the information uncovered during the Discovery Meeting.

A well-crafted investment plan can help ensure that your investment

decisions are based on rational analysis, which can help you avoid

making long-term investment decisions based on emotional respons-

es to short-term or one-time events. Each investment plan should

include these seven important areas of discussion:

• Your long-term goals, objectives and values. Long-term goals

can consist of anything from early retirement to purchasing a new

home to achieving nancial independence. ese goals are the

bedrock upon which your investment plan will be based.

• e expected time horizon for your investments. Your time

horizon consists of the period of time your portfolio is expected

to remain invested. For example, a 65 year old retiree should plan

for a potential time horizon of at least 25 to 30 years.

• A denition of the level of risk that you are willing and able to

accept. It is important for you to understand the amount of risk

you are willing and able to tolerate during your investment time

horizon. In designing your portfolio, your advisor will help you

determine both your nancial risk tolerance (the amount of loss

you might have to absorb in order to meet your goals) and your

emotional risk tolerance as well (the amount of loss that you can

accept without acting on your emotions by changing your prede-

termined asset allocation).

• e rate-of-return objective and asset classes that will be used.

Your advisor will help to identify the specic return/risk proles

of each potential portfolio, and use these proles as the frame-

work to determine your asset allocation.

• e investment methodology that will be used. We rmly be-

lieve that investors are best served by accepting a market rate of

return and using low-cost investment vehicles in order to try and

achieve that return.

• A rebalancing plan. You also will need to establish the means for

rebalancing and making periodic adjustments to the portfolio as

needed. Rebalancing your portfolio will help ensure it maintains

the desired risk and return parameters.

• Monitoring and reporting methods. Your goals won’t remain

static over time — they’ll change as your life changes. at’s why it’s

important to regularly monitor your portfolio and ensure it reects

where you are today and where you want to be down the road.

3. e Mutual Commitment Meeting. It’s important that you con-

sider the proposed investment plan thoroughly before committing

to work with a wealth manager. After you have reviewed the plan

carefully, this meeting will allow you to ask any questions or voice

concerns you have about the plan and decide whether to move ahead

with implementation.

4. e 45-Day Follow-up Meeting. is meeting allows your wealth

manager to help you understand and organize the nancial docu-

mentation involved in working together. It’s also an opportunity to

review any initial concerns and questions.

Chapter 3: The

Structured Wealth Management Solution

— 19

18 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 3: The

Structured Wealth Management Solution

— 21

5. Regular Progress Meetings. Regular Progress Meetings focus on

reviewing the steps you’ve taken toward meeting your various goals

and making any necessary adjustments based on changes in your

personal, professional or nancial situation.

e Discovery Meeting and Total Investor Prole

As noted above, one reason why wealth management can be so eective

in addressing investors’ needs is because of the Discovery Meeting, which

is focused on helping you identify your most important nancial goals.

e reality is, you simply cannot solve the complex and sometimes

conicting issues you face until you position your nancial assets around

the values, needs, goals and issues that are most signicant to you.

e Discovery Meeting enables you to identify all that is truly important

to you in seven key areas of your life. In working with an advisor, there

must be a close and thorough understanding between you in these seven

areas — an understanding that goes well beyond the simplistic aspects of

a typical investment review. Your answers to the types of questions below

will enable you to develop a holistic, all-encompassing picture of your

life goals so that your assets can be positioned appropriately:

1. Values. What is truly important to you about your money and your

desire for success, and what are the key, deep-seated values underlying

the decisions you make to attain them? When you think about your

money, what concerns, needs or feelings come to mind?

2. Goals. What do you want to achieve with your money over the long

run — professionally and personally, practically and ideally?

3. Relationships. Who are all the people in your life who are important

to you — including family, employees, friends, perhaps even pets?

4. Assets. What do you own — from your business to real estate to

investment accounts and retirement plans — and where and how are

your assets held? Conversely, what do you owe to lenders, and what

continuing obligations do you have (to family, charities, etc.)?

20 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 3: The

Structured Wealth Management Solution

— 21

5. Advisors. Whom do you rely upon for advice, and how do you feel

about the professional relationships you currently have?

6. Process. How actively do you like to be involved in managing your

nancial life, and how do you prefer to work with your trusted

advisors?

7. Interests. What are your passions in life — including your hobbies,

sports and leisure activities, charitable and philanthropic involve-

ments, religious and spiritual proclivities, and children’s schools

and activities?

If you have a spouse or partner, he or she should be equally involved in

this discussion. It’s not uncommon for couples to have diering values,

priorities or interests. Such dierences need to be recognized and

accounted for so that you have a better understanding and appreciation

of each other — and so that the plan you create can be eective in

meeting your collective goals.

Your wealth manager can then use that information to create a Total

Investor Prole that will serve as a roadmap — a guide so that every

nancial decision you make supports what you want most from life (see

Exhibit 3.1).

If, like many investors, you currently work with one or more nancial

advisors, you are probably aware that most use some type of fact-nding

process in the rst meeting. However, you may also have noticed that

these questions usually focus entirely on your investable assets and net

worth. In contrast, note that only one of the seven categories that make

up wealth management’s Total Investor Prole concerns assets. Six of

the seven are focused on helping you (and your wealth manager) better

understand who you are as a person. By engaging in this Discovery

Process and using the insights learned from it to create a personalized

prole, your wealth and all the choices you make about it become

perfectly aligned with the life you want to build for yourself, your

family and those you care about most.

20 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 3: The

Structured Wealth Management Solution

— 23

22 — The Wealth Solution

Exhibit 3.1: The Total Investor Profile

Assets

Goals

Advisors

Process

Relationships

Interests

Values

You

Of the seven categories that make up the Total Investor Prole, we

believe the most important is the one representing your values.

Values are one of the core motivations for everything we do in our lives,

and have a profound impact on every important decision we make,

from what we choose to do for a living to whom we marry to how we

spend our free time — in short, who we are as people. For example, if

you’re a parent you probably value your children above almost every-

thing else in the world. As a result, you want to protect them, to educate

them well and to set them onto a smooth path in life. Financially

speaking, one of the things you may want to do is build an adequate

college fund for your children’s education. is is a common goal.

But underlying that goal is the fundamental value of loving your

children. Values run the gamut from the basic — such as security,

nancial freedom and not having to worry about paying the bills —

to deeper such as family, community, faith and reasons for being.

As important as values are, however, most of us are not particularly

good at articulating them. e Discovery Meeting step can therefore

bring substantial advantages to the process of managing wealth

eectively by helping you uncover and clarify your core values.

One way to go about this is to ask yourself: “What is important to me

about money?”

Let’s say that your rst answer is “Security.” You would then want to ask

yourself, “Well, what is so important to me about security?” You might

decide that the answer is “Knowing that I can take care of my family.”

You would then ask, “What is important to me about taking care of my

family?” You would continue uncovering your values in this way until

there is nothing more important to you than the last value you stated. At

that point, you will have uncovered your single most important value.

While this is straightforward on the surface, it’s important to realize that

it takes perseverance to drill down to your most important value. Most

of us simply don’t spend a lot of time thinking about the issue. at is

why the best results occur by having a collaborative conversation about

values with an advisor.

In the following chapters, we’ll explore each of the three

main components of wealth management — investment plan-

ning, advanced planning and trusted advisory relationships — in

more detail. Armed with this information, you’ll be ideally

positioned to bring solutions to your nancial issues and achieve your

biggest goals.

Chapter 3: The

Structured Wealth Management Solution

— 23

22 — The Wealth Solution

24 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 4

e Investment Planning Process:

An Overview

Investment planning is the foundation of a properly Structured Wealth

Management plan. While not everyone needs to worry about minimizing

estate taxes or eective charitable giving strategies, all investors need to

position their nancial capital to provide them with the money they

need to live comfortably — both today and in the future. Without a

well-developed and carefully maintained investment plan, investors risk

not achieving their goals and failing to live the lives they want most.

For those reasons, chapters ve through nine of this book are devoted

to the investment planning process. Over the course of the next ve

chapters, you will learn (or be reminded of) the key principles used by

highly successful investors to guide their decisions. For example:

1. Beating the market is virtually impossible. Most active money

management strategies — such as stock picking and timing the

markets — have consistently failed to add value or give investors an

edge over the long term. is has held true in both bull and bear

markets throughout history. In fact, nancial markets operate in

ways that make it extraordinarily tough for investors to beat them

consistently.

2. Owning a broadly-diversied portfolio of stocks is a prudent

approach to investing. e power of capitalism and free markets

mean that it is not unreasonable for investors to expect stock prices

to gradually rise over time.

24 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 4: The Investment Planning Process — 27

3. Risk and Return are Related. Academic evidence suggests that there

are at least three types of risk worth taking. e rst is market risk:

Stocks have outperformed bonds over time. e second is size risk:

Shares of small companies have outperformed large-company stocks

over time. e third is value risk: Value stocks (those with high book-

to-market ratios) have generally outperformed growth stocks (those

with low book-to-market ratios) over time. By taking these risks,

investors may potentially generate stronger returns in their portfolios.

4. Structured diversication can reduce volatility and enhance

wealth. It’s impossible to know with certainty when an asset class

will outperform all others and when it will underperform. Structured

diversication — owning a mix of assets that have dissimilar price

movements and overweighting equities and small and value company

stocks — helps ensure that your portfolio is not over-exposed to any

single asset class that is performing poorly at a given moment. e

result: Your portfolio should experience more consistent returns from

year to year instead of more dramatic swings in value — which, in

turn, could enable your investments to build greater wealth for you

over the long run.

5. Building an ideal portfolio depends on each investor’s risk

capacity, risk tolerance and investment preferences. Building

a portfolio that is right for you will depend on your goals, income

needs and time horizon. You’ll also need to consider factors such

as your feelings about market volatility, your reaction to potential

declines in the value of your portfolio, and the types of investments

and asset classes that you prefer to own in pursuit of your objectives.

6. A disciplined long-term perspective is the key to staying on

track and realizing your key nancial goals. Once your portfolio

is created, let it do its job. at means staying invested instead of

trying to time market movements, avoiding unnecessary trading

and shutting down the many emotional and behavioral reactions to

economic and market developments that can lead to costly mistakes.

26 — The Wealth Solution

It also requires a system of regular portfolio rebalancing to ensure

that your portfolio’s desired risk/return characteristics remain in

place. Investors can maintain their disciplined approach by taking

advantage of resources such as investment policy statements to help

stay on track.

Some of the information contained in the following chapters will no

doubt be familiar — while some may surprise you. By the end, we

believe you will understand what it takes to build and maintain an

investment plan that maximizes your chances of achieving your goals.

Chapter 4: The Investment Planning Process — 27

26 — The Wealth Solution

28 — The Wealth Solution

56%

of intermediate fixed income

managers

underperformed the Barclays

Intermediate Government/

Credit Bond Index

Chapter 5

Markets Work

Few things are more exciting to investors than the prospect of beating

the market. If you can pick the right stocks and navigate your way

successfully in and out of various market sectors at the right times, or

nd money managers to do the job for you, you’ll generate outsized

returns that will get you to your goals faster and help you achieve the

lifestyle you desire. Not to mention that you’ll get to brag to your friends

and associates about the fortune you’re making.

It’s a wonderful and highly-appealing idea. Unfortunately, it suers

from a fatal aw: History suggests that it’s virtually impossible for even

experienced money managers to beat the market consistently. We believe

that by attempting to do so, you could put your nancial dreams, goals

and wealth at greater risk.

We realize that this probably isn’t the rst time you’ve been told that

your chances of beating the market are extremely slim. We nd that

most investors understand and believe this on some level. But beating

the market is such a tempting proposition that they often forget. And

when the markets run into trouble — as they did in recent years —

there’s always a resurgence of the idea that “things have changed” or “it’s

dierent this time,” which causes many investors to look for ways to try

and outperform the market as a whole.

Very few sources of information that investors access — such as nancial

advisors, the media and even academics — take the time to explain how

nancial markets work. In this chapter, we’ll show you not only that the

28 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 5: Markets Work — 31

markets are incredibly dicult to beat, but also why that’s the case —

regardless of whether we’re in a raging bull market or a volatile bear market.

Our point is not simply to show that investors’ attempts to beat the

market are largely futile. We believe that you don’t need to beat the

market to enjoy success as an investor. In fact, we think that the alternative

approach — capturing the overall rates of return oered by the market’s

major asset classes — may help put you in a stronger position to address

the major challenges you face and achieve the meaningful goals you’ve

set for yourself, as part of the wealth management consultative process.

e Case Against Active Management

Who wouldn’t want to outperform the market? Certainly many

investors and money managers devote a great deal of time and energy

trying. But all the long-term historical data boil down to one inescapable

conclusion: Trying to outperform the stock market’s overall rate of

return by actively trading stocks or engaging in market timing — has

seldom succeeded over the long run.

Consider some of the most recent evidence from what has become a

huge body of research over the years:

• Active management fails over short periods. A recent study by Standard

& Poor’s Index vs. Active Group (SPIVA) found that the S&P 500, the

well-known unmanaged index of large U.S. stocks, outperformed 62

percent of actively managed large-capitalization mutual funds during

the ve years through 2010. Meanwhile, the S&P Small Cap 600,

an unmanaged index of small U.S. stocks, performed better than 63

percent of actively managed small-cap stock mutual funds during that

period. e results were even more dramatic among non-U.S. stocks.

e S&P 700, an unmanaged index of international shares, beat 82

percent of actively managed international stock funds (See Exhibit 5.1).

30 — The Wealth Solution

Exhibit 5.1: Active Mutual Fund Manager 5-Year Performance

from 2006 – 2010

Active Money Managers Have Difficulty Beating the Market

56%

of intermediate fixed

income managers

underperformed the

Barclays Intermedi-

ate Government/

Credit Bond Index

62%

of large-cap

managers

underperformed

the S&P 500

Index

63%

of small-cap

managers

underperformed

the S&P SmallCap

600 Index

82%

of international

managers

underperformed the

S&P700 Index

Source: Standard and Poor’s Index Versus Active Group, March 2011 (For the period 1/05 – 12/09)

Indexes are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses

associated with the management of an actual portfolio. The fund returns used are net of fees,

excluding loads. Returns are based upon equal-weighted fund counts. The data assumes

reinvestment of income and does not account for taxes or transaction costs. The risks associated

with stocks potentially include increased volatility (up and down movement in the value of your

assets) and loss of principal. Bonds are subject to risks, including interest rate risk which can

decrease the value of a bond as interest rates rise. Investing in foreign securities may involve

certain additional risks, including exchange rate fluctuations, less liquidity, greater volatility,

different financial and accounting standards and political instability. Past performance is not a

guarantee of future results.

Additionally, the majority of actively managed funds in seven common

equity categories underperformed their various benchmark indices

during the ve years through December 2010 (see Exhibit 5.2).

Chapter 5: Markets Work — 31

30 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 5: Markets Work — 33

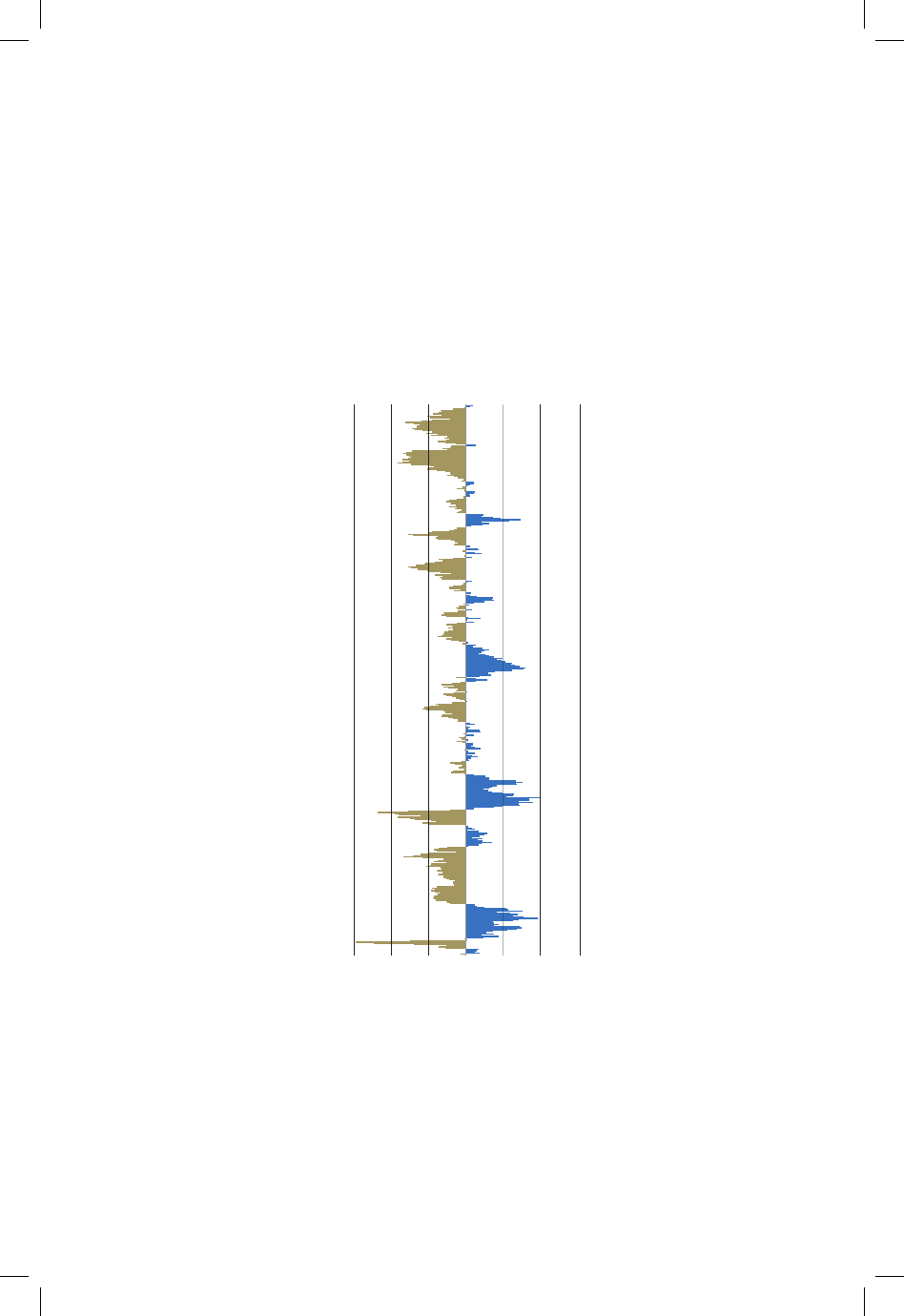

Exhibit 5.2: Percentage of Active Public Equity Funds that

Failed to Beat Their Indices

(January 2006 – December 2010)

US Large

Cap

US Mid

Cap

US Small

Cap

Global International International

Small

Emerging

Markets

62%

78%

63%

60%

82%

24%

90%

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Equity Fund Category

% of Active Funds that Failed to

Outperform Benchmark

Source: Standard & Poor’s Indices Versus Active Funds Scorecard, March 2011. Index used for

comparison: US Large Cap — S&P 500 Index; US Mid Cap — S&P MidCap 400 Index; US

Small Cap — S&P SmallCap 600 Index; Global Funds — S&P Global 1200 Index; International

— S&P 700 Index; International Small — S&P Developed ex. US SmallCap Index; Emerging

Markets — S&P IFCI Composite. Data for the SPIVA study is from the CRSP Survivor-Bias-Free

US Mutual Fund Database.

32 — The Wealth Solution

Exhibit 5.3: Percentage of Active Managers Who Outperform Due to Skill

Universe of Active Mutual Fund Managers 1975-2006

0.6% Outperformed their

Benchmark Due to Skill

• Activemanagementfailsoverlongperiods.In a 2008 research study

12

— perhaps the most comprehensive ever performed — a team of

professors used advanced statistical analysis to evaluate the performance

of active mutual funds. ey looked at fund performance over a 32-

year period, from 1975-2006.

e study concluded that after expenses, only 0.6% (1 in 160) of

active mutual funds actually outperformed the market through the

money manager’s skill (see Exhibit 5.3). e study concluded that this

low number “can’t eliminate the possibility that the few [funds] that

did were merely false positives.” In other words, they were just lucky.

Recent research, conducted by Eugene Fama of the University of

Chicago and Kenneth French of Dartmouth, further supports these

ndings of luck versus skill.

13

In their research, they found that

managers of actively managed funds, as a whole, possess only enough

skill to cover their trading costs. Fama and French conducted 10,000

_________________________

12 Barras, Laurent, Scaillet ,Wermers, and Russ, “False Discoveries in Mutual Fund Performance:

Measuring Luck in Estimated Alphas” (May 2008).

13 Fama, Eugene F. and French, Kenneth R., Luck Versus Skill in the Cross Section of Mutual Fund

Returns (December 14, 2009). Tuck School of Business Working Paper No. 2009-56 ; Chicago

Booth School of Business Research Paper; Journal of Finance, Forthcoming. Available at SSRN:

ssrn.com/abstract=1356021

Chapter 5: Markets Work — 33

32 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 5: Markets Work — 35

simulations of the eect of luck on fund returns and found that, “e

challenge is to distinguish skill from luck. Given the multitude of

funds, many have extreme returns by chance.”

Despite the existence of these lucky few outliers, Fama and French

concluded that very few fund managers have superior enough skills to

beat their indices, once costs were taken into consideration.

e research is further evidence that the majority of strong performing

managers are simply lucky rather than skillful traders and that top-

performing managers are unlikely to noticeably outperform large

index funds in the future.

e inability of active money managers to beat their respective market

indices isn’t limited to stocks. As seen in Exhibit 5.4, the vast majority

of active xed-income managers — close to 100% in some instances

— have failed to outperform their benchmarks.

34 — The Wealth Solution

Exhibit 5.4: Percentage of Active Fixed Income Funds that Failed to

Beat Their Indices

January 2006 – December 2010

Government

Long

Government

Intermediate

Government

Short

Investment-

Grade Long

Investment-

Grade

Intermediate

Investment-

Grade Short

National

Muni

68%

68%

75%

70%

56%

97%

86%

CA Muni

98%

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Fixed Income Category

% of Active Funds that Failed to Outperform Benchmark

Source: Standard & Poor’s Indices Versus Active Funds Scorecard, March 2011. Index used for

comparison: Government Long — Barclays Capital US Long Government Index; Government

Intermediate — Barclays Capital US Intermediate Government Index; Government Short — Barclays

Capital US 1-3 Year Government Index; Investment Grade Long — Barclays Capital US Long

Government/Credit; Investment Grade Intermediate — Barclays Capital US Intermediate Government/

Credit; Investment Grade Short — Barclays Capital US 1-3 Year Government/Credit; National Muni

— S&P National Municipal Bond Index; CA Muni — S&P California Municipal Bond Index. Data for

the SPIVA study is from the CRSP Survivor-Bias-Free US Mutual Fund Database. Barclays Capital data,

formerly Lehman Brothers, provided by Barclays Bank PLC.

e evidence leads to three conclusions: 1) Historically, it has been extremely

dicult for most active management strategies to outperform the market

over short periods such as ve years, 2) Most active managers have also failed

to outperform the market over long periods and 3) A successful investment

experience is not dependent on outperforming the market.

ese points are especially important to keep in mind. After all, many of

your most important goals in life are a decade or more away — such as

ensuring that you have enough money to see you through a retirement

that could last twenty or thirty years or even longer.

Chapter 5: Markets Work — 35

34 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 5: Markets Work — 37

What About Bear Markets?

Some investors believe that while active managers will always have a

tough time beating the market when times are good, active managers’

market-beating abilities will be revealed during bear markets when lots

of negative trends are hurting the market. Stock pickers and market

timers, the argument goes, can use their intelligence and insight to

sidestep the worst stocks with the poorest prospects or avoid entire asset

classes and sectors that stand to get pummeled during a downturn.

Unfortunately, for these active managers, the research shows otherwise. For

evidence, we only have to look as far back as 2008 — the year of the Great

Recession, that saw U.S. stocks (as represented by the S&P 500 Index)

plummet 37 percent in the wake of the worst global nancial crisis since

the 1930s. at year, actively managed funds as a group underperformed

the S&P 500 by an average of 1.6 percent (see Exhibit 5.5). SPIVA also

found similar results in 2003 when it reviewed the performance of actively

managed funds during the 2000 to 2002 bear market.

Exhibit 5.5: Active Manager Performance During the 2008 Bear Market

Average U.S.

Equity Fund

Manager

Underperformed

S&P 500 by

1.67%

Source: Standard and Poor’s Investment Service, May 2009. Indexes are not available for direct

investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management

of an actual portfolio.. The data assumes reinvestment of income and does not account for taxes

or transaction costs. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

36 — The Wealth Solution

Why Has Active Management Failed So Often?

e case against active management is compelling. Yet many investors

have a dicult time accepting the facts. It’s extremely tempting to think

that if we make smart investment decisions we can outperform the

market — or nd a hard-working, brilliant money manager or advisor

who can do the job for us. After all, just because many active managers

have struggled to beat the market in the past doesn’t mean that someone

won’t be able to do so in the future, right? If you can nd that manager

and give him or her all your money today, you’ll be rich in no time.

We understand how powerful and motivating that idea can be when

making investment decisions. To be honest, there’s nothing we’d like

better than to nd a manager who could beat the market year in and

year out for decades and make us fabulously wealthy, too.

e problem with this thinking is that the nancial markets operate

in ways that make beating them extraordinarily dicult, even for the

world’s smartest managers. Specically, there are ve challenges that

active managers face in trying to outperform the overall market:

Challenge 1: Success Requires Predictive Ability

Wall Street and the popular nancial press want you to believe that

in order to make money in the market, you need to invest based on

what’s about to happen. at’s the message sent out every day by market

strategists, brokers, analysts, mutual fund managers and the media —

predict the future accurately, and you’ll score big.

In truth, there is no crystal ball when it comes to investing your money.

No one can accurately forecast market movements on a consistent basis

over the long term. Why? Because we’re talking about the future, and the

future is by its very nature and denition unknowable. We simply cannot

know with certainty the future direction of the economy, stock prices

or the myriad events and developments that will occur that will have an

impact on the markets.

Chapter 5: Markets Work — 37

36 — The Wealth Solution

Chapter 5: Markets Work — 39

Ah, but what about the countless PhDs and other experts on Wall Street

who devote their time to sizing up economic and market developments

and using their insights to make predictions? Surely they must have an

ability to gauge the future that the rest of us lack?

For the answer, consider the following Wall Street predictions for where

the S&P 500 would stand on December 31, 2008:

Morgan Stanley ...................................................... 1520

Merrill Lynch ........................................................... 1525

A.G. Edwards ......................................................... 1575

Wachovia Securities .............................................. 1590

JP Morgan Chase .................................................. 1590

Bank of America Securities .................................... 1625

Goldman Sachs ...................................................... 1675

Citigroup ................................................................. 1675

Strategas Research Partners ................................... 1680

For the record, the S&P 500 ended 2008 at 903.

14

In other words, none

of these highly experienced rms, with access to a wealth of resources and

information was able to predict even the down direction of the market

that year.

Or take something as seemingly simple as predicting how the broad

economy is going to do. As the New York Times noted in a May 5, 2009

article, “Amazingly enough, Wall Street’s consensus forecast has failed to

predict a single recession in the last 30 years.”

15

e media’s track record is equally abysmal. One of the most famous

examples is Business Week’s August 13, 1979 cover story, “e Death of

Equities.” e article inside reached the conclusion that “e death of

equities looks like an almost permanent condition — reversible someday,

but not soon.”

38 — The Wealth Solution