King George the III was twenty- ve years

old in 1764. Although not an absolute monarch,

he wielded considerable power over the world’s greatest empire. Some thought

that the young king put his con dence in the wrong people. “We must call in bad

men to govern bad men,” he explained.

Deeply in debt a er the French and Indian War, the King’s advisors proposed

two unpopular revenue measures for the colonies: e Sugar Act of 1764 and the

Stamp Act of 1765.

e Sugar Act included a customs duty paid by merchants. It was unwelcome but

not unfamiliar. e Stamp Act was something new, a direct, internal tax that

a ected most colonists. Former Prime Minister William Pitt had known better.

When the idea was proposed to him a few years earlier he had declined “to burn

[his] ngers with an American Stamp Act.” Now nearly every piece of paper in the

colonies would require a revenue stamp. ere was a restorm of protest.

School children know what happened next: the debate about “taxation without

representation,” the birth of the Liberty Tree and the Sons (and Daughters) of

Liberty, the role of James Otis, Samuel Adams, and John Hancock. e story is

familiar but not the back story. e events of 1765, two hundred and y years

ago, started a complex debate about the principles of government, the importance

of individual rights, and the identity of colonists as “Americans.”

I

Road to Revolution:

The Stamp Tax Crisis of 1765

2

In 1760 a Boston newspaper reported on the

lavish coronation of King George the ird.

A Tale of Two Cities

King George III in coronation robes

National Portrait Gallery, London

is bucket, owned by merchant John Rowe, was used

to ght the re of 1760. Boston’s Rowe’s Warf still bears

his name. Boston Fire Historical Society

Many local ministers preached sermons

on the Boston re as well as the small pox

epidemic. Some saw them as warnings to

repent. Boston Fire Historical Society

Boston 1760–1765

A great re engulfed the town of Boston in 1760. Raging for three

days it destroyed 174 houses, 175 shops and le 220 families

homeless. Lacking re insurance many were wiped out nan-

cially. e re was followed in 1764 by a devastating small

pox epidemic.

Victory in the French

and Indian War (the

North American phase

of the Seven Years War)

brought celebration but

also economic recession.

Merchants had grown

rich supplying British

forces. Now, some

began to struggle.

Tax collectors, like

Samuel Adams, showed

leniency.

London 1760–1765

“ e King’s herb woman” began the coronation proces-

sion, “with her six maids, two and two throwing sweet

herbs.” e Queen’s garment,” the richest thing of this

kind ever seen,” was “valued at one hundred thousand”

pounds.

Ironically George’s realm faced a staggering debt. In

1763, with success in the Seven Years War, Britain

emerged as the greatest world power. By one estimate

its debt reached 122.6 million pounds that year on an

annual budget of eight million.

e young king pressed his ministers for revenue.

three

s

n-

3

Taxing Matters

“

That a Revenue be raised in Your Majesty’s

Dominion in America defraying the expenses of

defending, protecting and securing same...”

Preamble to the Sugar Act 1764

Among colonial ports, Boston was

locked in the deepest recession

when news arrived of two revenue

measures, the Sugar Act of 1764,

and Stamp Act of 1765.

Sugar Act, 1764

e Sugar Act especially damaged

Boston merchants. Many depended

on the importation of molasses –

produced by slave labor in the West Indies

– for the production of rum. By 1750 Mas-

sachusetts exported two million gallons per

year. While the Sugar Act reduced the cus-

toms duty on imported molasses, a crack

down on smuggling brought a sense of

harassment to Boston merchants. It also

produced a sharp decline in trade.

Stamp Act, 1765

e Stamp Act was a formidable document –

13,000 words, in 63 sections, each marked

by a Roman numeral. It seemed that nearly

every piece of paper required a stamp: real

estate transactions, wills and other legal doc-

uments, newspapers, broadsides, almanacs,

bills of sale, liquor licenses, even playing cards.

e courts could not open without them nor

would ships be allowed to sail. Omi-

nously the penalty for making coun-

terfeit stamps was death “without

bene t of clergy.”

A two pence stamp

Courtesy of the Bostonian Society

e Virginia House of Burgesses

was in session when the Stamp

Act was announced. Patrick

Henry became famous for his

vehement protest. He may have

been in uenced by arguments

circulated by Samuel Adams

against the Sugar Act the previ-

ous year. Henry said that colo-

nial legislatures, not Parliament,

had the right to levy taxes — a

theme that resounded across the

American colonies. Patrick Hen-

ry Memorial Foundation

Taxation with Representation

In 1755 the Massachusetts Assembly approved a Stamp Tax to fund the French and

Indian War. Designs are described in this proclamation: a schooner with the motto,

“Steady : Steady,” a Pine Tree with the words “Province of the Massachusetts,” and

a cod sh with the words, “Staple of the Massachusetts.” ere was some grumbling

but acceptance because the tax was approved by the Massachusetts legislature.

Massachusetts Archives

Ruminations on the Sugar Act

New Englanders consumed a million and

a quarter gallons of rum each year – the

equivalent of four gallons for every man

woman and child. Rum also played a

central role in the African slave trade.

d

o

h

a

p

A

two

pe

nce stam

p

4

The View from

King Street

“

My temper does not incline

to enthusiasm.”

Lieutenant Governor

Thomas Hutchinson

More than any other o cial in

Boston, omas Hutchinson

came to personify unpopular

British policies.

Thomas Hutchinson

At the time of the Stamp Act omas Hutchinson

served simultaneously as lieutenant governor and

chief justice. His brother-in -law Andrew Oliver was

designated as Stamp Tax agent. Privately, Hutchinson

counseled against the Stamp Act but publicly defended

Parliament’s authority to tax the colonies. Out of step

with a growing democratic spirit, Hutchinson became

a lightening rod. “He was never able to empathize with

people who were not, as he was, part of the establish-

ment,” wrote his biographer Bernard Bailyn.

omas Hutchinson hoped to suppress dissent. His mind ran toward

“ rmness not subtlety” wrote Bernard Bailyn. “He didn’t understand

people who were sensitive to what power was because they had

never been able to share in it.” Massachusetts State House Arts

Collection

Located on the former

“King Street,” the Boston

Town House (now the

Old State House) was the

seat of British govern-

ment in Massachusetts.

e lion and unicorn

symbolized royal power.

Arguing before Chief Justice omas

Hutchinson, whom he resented

personally, James Otis rallied opin-

ion against the “writs of assistance,”

broad search warrants issued to

restrict smuggling during the French

and Indian War. Later he protested

“taxation without representation.”

Brilliant but unstable, Otis eventually

withdrew from public life.

Massachusetts State House Arts

Collection

A Talent for Making Enemies

When Hutchinson, who was not a lawyer,

accepted the position of Chief Justice, he

angered the Otis family. e position had

been promised to James Otis, Senior, father

of “patriots” James Otis and Mercy Otis

Warren.

James Otis reportedly pledged to “set

the whole province in a ame” a er

Hutchinson’s appointment as Chief

Justice. Library of Congress

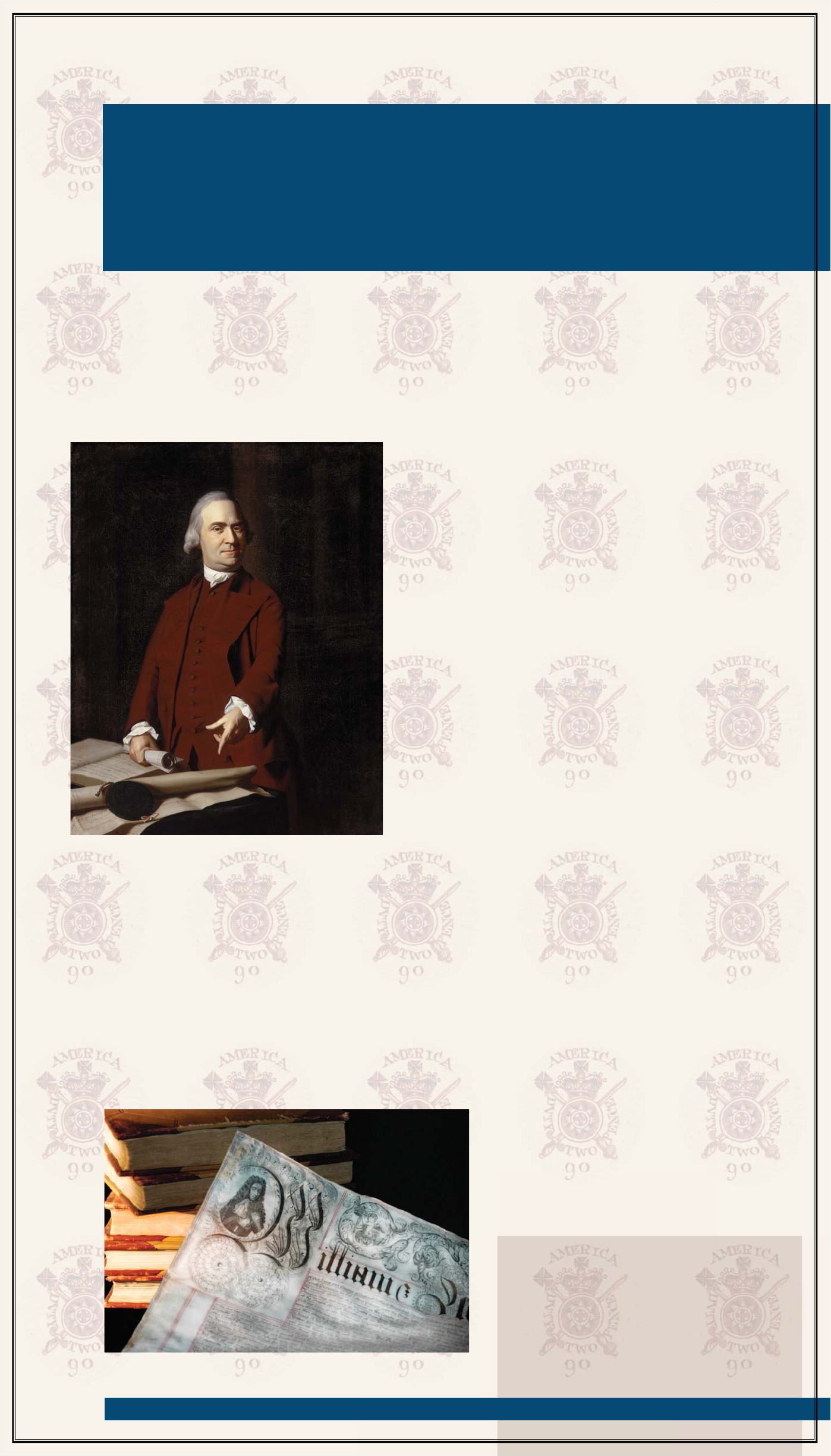

Samuel Adams by

John Singleton Copley.

Museum of Fine Arts,

Boston

Mercy Otis Warren later wrote “melo-

dramas” satirizing the role of omas

Hutchinson. Museum of Fine Arts

The Adams Family

Samuel Adams father, Deacon Samuel

Adams, was active in establishing a

“land bank.” Farmers could borrow

paper money against the value of their

land. Hutchinson favored “hard money,”

gold and silver. He campaigned to destroy

the bank and Deacon Adams was ruined

fi nancially. His son Samuel inherited

debts and lawsuits.

HthihpdtppditHiidtd

5

e Commonwealth Museum’s Revolution

Gallery displays a facsimile of an

eighteenth century printing press.

The View From Chase

and Speakman’s Distillery

“

I was very cordially and respectfully treated by all

present. We had punch wine, pipes and tobacco,

biscuit and cheese etc.” John Adams describing a

meeting at Chase and Speakman’s

Wealthy colonial mer-

chants like omas

Hutchinson tended to

accept British policy.

People of the “middling

sort” were struggling

through hard economic

times.

A soon to be famous Elm tree was visible from the meeting place of the

Loyall Nine. Old Boston Taverns and Tavern Clubs, by Samuel Adams

Drake and Walter K. Watkins

The Loyall Nine

In a counting room at Chase and Speakman’s Distillery,

overlooking a prominent Elm tree, a group began meet-

ing to discuss the new taxes, and organize protests.

Although not wealthy they were substantial citizens.

Two distillers and a sea captain had been shut down for

smuggling. A newspaper editor, Benjamin Edes, would

become a master propagandist. ey called themselves

the “Loyall Nine.” Although not a member, Samuel

Adams attended their meetings.

Several members of the Loyall Nine had been

accused of smuggling. is Parliamentary re-

port from 1751 concluded “e ectual remedies

must be found to keep the British trader in

North America within bounds.” With histor-

ical hindsight, perhaps more thought should

have been given to this issue. Massachusetts

Archives

The Boston Gazette

and Country Journal

Benjamin Edes was a

member of the Loy-

all Nine. With partner

John Gill he produced

an in uential newspaper that challenged British policy. e Boston

Gazette and Country Journal began a drumbeat of criticism against

the Stamp Act and helped de ne issues for general readers. Printers

feared that the added expense of the tax could actually put them out

of business. In an early version of social media

they also printed broadsides and announcements

that attracted crowds to demonstrations and

protests.

e Boston Gazette and Country Journal encouraged

Stamp Tax protests. Massachusetts Historical Society

What’s in a Word? Caucus

Today the word caucus represents a political faction. Possibly the

word originated in Boston during this period. Political clubs were

forming, often representing economic interests. The Caulkers Club

met in the North End, the town’s center for shipbuilding. (Wood-

en ships used caulking between planks to prevent leaks.) The term

“caucus” may be derived from the name of this group.

AsoontobefamousElmtreewasvisiblefromthemeetingplaceofthe

6

The View from the StreetThe View from the StreetThe View from the Street

“

In the fray many were much bruised and

wounded in their heads and arms some

dangerously.” Account of Pope Night,

Evening Post, November 11, 1764

e Stamp Tax crisis brought

disadvantaged groups into

the political process in ways

that were unsettling to British

colonial o cials.

The Outsiders

In the eighteenth century they were called

the “people out of doors,” to signal that they

were outsiders in the political process. e

“people in doors” made policy. At the top

were respectable artisans, “the butcher, the

baker, the candlestick maker,” according to

historian Alfred Young. Below them was an

angry group of unemployed dockworkers,

sailors, transients, and the very poor. ey

were receptive to the idea that British pol-

icies were responsible for their plight and

ready to protest, even violently, whatever

needed protesting.

is painting depicts one of the “leather apron” men who

worked with their hands and were called “mechanics” during

the eighteenth century. Later Samuel Adams convinced some

to give up their leather aprons as part of a boycott of British

goods. Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

Pope Night in Boston

Library of Congress

Pope Night

November 5th was called

Pope Day in Boston. It

echoed the annual celebra-

tion of Guy Fawkes Day

in England when a plot by

Catholic dissidents to blow

up Parliament was foiled.

at evening North and

South End gangs carried

e gies of the Pope and the

devil before descending

on each other with rocks,

sts, and clubs. In 1764 a

child was killed when run

over by a cart. Samuel

Adams thought that these

energies could be put to better use and introduced

himself to the leader of the South End gang.

Henry Knox by Gilbert Stuart

Museum of Fine Arts

is petition from the Massachusetts

legislature to King and Parliament

protests the Stamp Act’s burden on the

poor. e rural population will have

di culty traveling “forty to y miles”

to the “metropolis” to buy stamps.

“Besides it was found that this tax lay

heaviest on the poor sort, and those

least able to bear that or any other

tax.” Massachusetts Archives

Youthful Indiscretions

For a time in the 1760’s Henry Knox, hero of the

American Revolution and President Washington’s

Secretary of War, was a lieutenant in the South

End gang.

7

The View from

Samuel Adams Study

“

This we apprehend annihilates our Charter

Rights to govern and tax ourselves.”

Samuel Adams, on the Sugar Act, 1764

To omas Hutchinson he

was the “Grand Incendiary.”

Others have dubbed him

the “Father of the American

Revolution.” Samuel Adams

came to prominence during

the Stamp Tax crisis.

Samuel Adams by John Singleton Copley

Adams is dressed simply be tting his democratic values and Puritan

ancestry. He points to the 1691 province charter. Adams alleged many

British violations of the charter particularly its provisions for taxation.

He also holds instructions from Boston Town Meeting to its delegation

in the General Court. e original charter is on display in the Com-

monwealth Museum Treasures Gallery. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Samuel Adams

He preferred to be called Samuel, or Mr. Adams, not the

more diminutive “Sam.” Yes, he inherited a malt business

but Adams was no businessman. at is not to say that

he was impractical. He had a genius for organization and

propaganda. Adams cra ed arguments to appeal to each

segment of the population and developed innovative

methods to spread his message from Boston, to other

Massachusetts towns, to the thirteen American colonies,

and London itself.

A Theory of the Case

Most people did not like taxes but Samu-

el Adams put the issue into a moral con-

text. “Taxation without representation”

was not merely unpleasant but a denial

of self-government. People who had no

role in making decisions for themselves

were reduced to the status of slaves.

Adams saw that British e orts to stop

dissent would further erode rights.

Admiralty courts in Halifax – trying

violations of the Sugar and Stamp Acts –

undermined the tradition of trial by jury.

Royal governors dismissed unruly legis-

latures elected by the people. Adams

predicted that British troops would be

called in one day.

Detail of the 1691 “William and Mary Charter” shown in Copley’s portrait

of Samuel Adams. Commonwealth Museum Treasures Gallery

Taxachusetts?

In the seventeenth century Massachusetts had the highest

taxes among the American colonies. An interest in edu-

cation was one reason. In a world historic experiment,

the Puritan government mandated the establishment

of public schools. People approved taxes through town

meeting or through representatives elected to the “General

Court.”

8

Locke wished to justify the “Glorious Rev-

olution” of 1689 that replaced King James

II with a limited constitutional monarchy.

He described the “state of nature” before

government was established. ere were

natural rights, most importantly “life,

liberty, and property.” Natural law protected them and could

never be breached. To protect rights and improve living condi-

tions people formed a government with limited powers through

a social contract. If a ruler violated rights revolution was justi ed.

ese ideas, particularly the concept of “natural rights” and

“natural law” were re ected in the rhetoric of the Stamp Tax

crisis. Rowdy mobs chanted “Liberty, Property, and No Stamps.”

Where did you get those ideas, Mr. Adams?

e Puritan eet, with agship Arbella, arrived to es-

tablish the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. W.F.

Halsall, An Elementary History of Our Country, by

Eva March Tappan

Samuel Adams combined the moral outlook of seventeenth

century Puritans with an eighteenth century belief in rights

and limited constitutional government.

Samuel Adams was deeply conscious of his Puritan ancestry.

English Puritans fought a civil war against the King and aris-

tocracy, seeing them as corrupt and repressive. e lingering

in uence of Boston’s Puritan founders helps explain Massa-

chusetts’ role in events leading to the American Revolution.

Old South Meeting House

Samuel’s father “Deacon Samuel

Adams” had a profound in uence.

He had a malt business but was

deeply religious and active in the

Old South Meeting House. He was

also a skilled politician who taught

his son the art of retail politics by

visiting taverns and political clubs.

e Commonwealth Museum Treasures Gallery displays

the 1691 Province Charter. Massachusetts Archives

Deacon Adams and friends discussed issues

surrounding the province charter. Granted

by King William and Queen Mary in 1691, it

had a frame of government and rules for gov-

erning. Young Samuel Adams learned that the

document was important for protecting rights.

He called it our “Magna Carta.” Legalistic

arguments, based upon the charter, were

central to Adams message.

Harvard College

Library of Congress

Puritans founded Boston Latin

School and Harvard College.

Adams was an alumnus of both.

At Harvard Samuel studied history

and modern political theory. Like

many, he was deeply in uenced

by the writings of John Locke and

other Enlightenment thinkers.

Green Dragon Tavern Old Boston Taverns

and Tavern Clubs, by Samuel Adams Drake

and Walter K. Watkins

Above all, Samuel Adams was a true

democrat who valued the opinion of

common people. He frequented taverns

to gauge public sentiment and worked

to establish an elected government

responsive to the will of the people. In

contrast to many revolutionaries he did

not seek personal power.

John Locke

Library of Congress

9

Liberty!

“

Armed with axes – the British soldiers made a

furious attack upon it...foaming with malice

diabolical, they cut down a tree because it bore

the name of Liberty.” Essex Gazette, 1775, after

British evacuation of Boston

For Samuel Adams August 14, 1765 was a day to

be remembered and celebrated. It began with an

episode of street theater.

Birth of the Liberty Tree

At Boston Neck, the one road into town, visitors were stopped

in a playful manner to check for stamps. Soon an e gy of

stamp agent Andrew Oliver was hung from the branches of

the Elm tree near Chase and Speakman’s Distillery. Decora-

tions included a large boot with a devil peeking out, a refer-

ence to Lord Bute one of the King’s ministers.

Later in the evening a rougher crowd gathered, cut down the

e gies and paraded them past the Town House. ey be-

headed the e gy of Andrew Oliver, demolished a building

thought to be the potential stamp o ce, and vandalized Oli-

ver’s home. Oliver resigned as stamp agent the next morning.

Stamp Tax protesters hung e gies in Massachu-

setts and other colonies. Marchand Archive

is announcement

by the Sons of Liberty

summoned Andrew

Oliver to appear be-

fore the Liberty Tree

to resign a second

time as stamp agent.

Massachusetts His-

torical Society

Sons of Liberty

In the British Parliament, Isaac Barre opposed the Stamp

Act. A veteran of the French and Indian War he was sym-

pathetic to Americans. Although he did not originate the

phrase, Barre called American dissidents “Sons of Liberty.”

As their support grew, the Loyall Nine began issuing state-

ments under that name. Barre Massachusetts is named for

Isaac Barre.

“A number of Spirited papers I have of Edes and

Gill to stir up the S...of L...and procure an elec-

tion next May.” is letter to omas Hutchin-

son from Judge John Cushing uses an abbrevia-

tion for the phrase “Sons of Liberty.” Perhaps it

was not politically correct to spell out the name.

February 2, 1766, Massachusetts Archives

Where was the Liberty Tree?

Offi cially named the “Tree of Liberty”

the old Elm was located at the corner of

today’s Boylston and Washington Streets in

downtown Boston. It was the site of many

demonstrations until chopped down by

British soldiers before evacuating Boston.

Isaac Barre.

Brooklyn Museum

Today, markers identify the site of Boston’s Liberty Tree.

b

s

O

f

t

t

M

t

Crossing the Line

“

Liberty and Property ... the Usual Notice of their

Intention to plunder and pull down a house.”

Governor Francis Bernard describing the chant

of Boston mobs

10

On the evening of August 26,

1765 a mob destroyed the

home of Lieutenant Governor

omas Hutchinson, one of

the most elegant buildings in

North America.

e attack on omas Hutchinson’s home

National Park Service © Louis S. Glanzman

Destruction of Hutchinson’s Home

Bent on total destruction and forti ed

with alcohol, angry protesters broke down

the front door with axes, ripped paneling

and wainscoting from walls, proceeded to

destroy inner walls, furniture, and paint-

ings, and carried o silver and clothing.

Hutchinson’s notes for a history of Massa-

chusetts were scattered and mud stained.

( e notes, discolored with mud, remain in

the vaults of the Massachusetts Archives.)

Seeking compensation, Hutchinson submitted this meticulous list of

damages. In addition to personal property he claims reimbursement

for “a plain lawn apron” for Susannah, a maid, and a “new cloth

coat” for “Mark negro.” A er a delay, Hutchinson was reimbursed

by the legislature. Massachusetts Archives

Ebenezer Mackintosh — Captain of

the Liberty Tree

Shoemaker Ebenezer Mackintosh, the

leader of the South End gang, was arrest-

ed a er the destruction of Hutchinson’s

home. Samuel Adams secured his release

but may have had second thoughts. Mack-

intosh was given a blue and gold uniform

as “Captain of the Liberty Tree” but sur-

rounded by more

respectable Sons

of Liberty in later

peaceful demonstra-

tions.

Mackintosh also participated in the

Boston Tea Party before moving to

Haverhill, New Hampshire. is his-

torical marker highlights other events

in his life. New Hampshire Depart-

ment of Transportation

is is the only contemporary

drawing of Hutchinson’s coun-

try home. Milton Historical

Society

Hutchinson’s Country House

Thomas Hutchinson also had a country

home in Milton overlooking the Nepon-

set River Valley. The home no longer stands but “Governor Hutchinson’s

Field” remains as conservation land. Close by is the birthplace of Presi-

dent George Herbert Walker Bush. Like Thomas Hutchinson, Bush is a

descendant of Puritan dissident Anne Hutchinson. Other Anne Hutchin-

son descendants include Franklin Roosevelt and Mitt Romney.

Seeking compensation, Hutchinson submitt

ed

this meticulous list of

thi

s

11

Reaching Out

Samuel Adams advocated a Stamp

Tax Congress to unite the colonies

and a boycott of British goods to gain

the attention of London merchants.

“

There will be a necessity of stopping in a

great measure the importation of English

goods.” Samuel Adams to Massachusetts’

agent in London Dennys DeBerdt

The Stamp Tax Congress

e Stamp Tax Congress was a Massachusetts initiative.

In June 1765 the House of Representatives voted to

contact each colonial legislature with the idea. Delegates

met in New York in October. Petitioning the King and

Parliament, Congress maintained that taxation without

representation was a violation of basic rights and that

Admiralty courts trying o enders in Halifax were illegal.

Christopher Gadsden of South Carolina captured the

spirit: “ ere ought to be no more New England men,

no New Yorkers... but all of us Americans.”

e Stamp Tax Congress met in New

York’s City Hall on Wall Street. Later

known as Federal Hall, it was the site

of President Washington’s inaugura-

tion. Library of Congress

James Otis played a prominent role in debates

but was showing signs of instability. Returning

to Boston he challenged British Prime Minister

George Grenville to resolve the issue by ghting

it out, one on one, on the oor of the House of

Commons. He died in dramatic fashion when

struck by lightening. Wichita Art Museum

For a time British businessman Richard Jackson rep-

resented Massachusetts’ interests in London. Alarmed

by news of the Stamp Tax Congress, he warns:

“I cannot express my concern for what has happened

in America, God knows what the Consequences will

be, sure I am that the Congress of the Americans

will weaken the power of their friends here to service

them.” Massachusetts Archives

Non-Importation

Samuel Adams realized that London merchants

were vulnerable to the boycott of English goods

and worked to persuade merchants in Boston,

New York and Philadelphia to stop imports.

Two hundred New York merchants, 400 Phila-

delphia merchants, and 250 Boston merchants

joined. British exports to the colonies quickly

declined by 14% and many English merchants

began to panic.

This 1770 article in the

Boston Gazette uses the

phrase “Daughters of

Liberty.”

Women played a signifi cant

role in the boycott by discourag-

ing neighbors from buying Brit-

ish goods and substituting home

made products. In 1765 many

Boston women agreed not to

serve lamb in order to increase

the production of wool.

12

Merchant Prince

“

The town has done a wise thing this

day. They have made this young

man’s fortune their own.” Samuel

Adams to his cousin John, on the

occasion of John Hancock’s election

to the Massachusetts legislature,

1766

In November 1765 John

Hancock, reputedly Boston’s

wealthiest merchant, publicly

sided with Samuel Adams in

opposition to the Stamp Tax.

Taking a Stand

John Hancock observed attacks on the homes of

Oliver and Hutchinson with concern. He did not

wish to be next. Yet he had genuine sympathy for

the poor and a desire for popularity. Privately

he had written to his London agents protesting

the Stamp Act. In November 1765 he signed a

non-importation agreement. Not yet married, he

wrote a note in his letterbook to document his

stand for future Hancock children. “It is the

united Resolution & Determination of the people

here not to Carry on Business under a Stamp.”

John Hancock by John Singleton Copley. Museum of Fine Arts,

Boston

John Hancock’s Beacon

Hill Home. Its destruction

during the nineteenth

century stimulated the

historic preservation

movement.

While Hancock’s Boston

home no longer stands,

visitors can see the child-

hood home of his wife

Dorothy Quincy (in the

city of Quincy.) It became

a meeting place for Han-

cock and other patriots

before the revolution.

Quincy Sun Photo/Robert

Noble

Pope Day 1765

November 1 was the date for implementation

of the Stamp Act. In Boston the stamps were in

storage at Castle William (now Castle Island.) It

was too dangerous to unload them. On October

31st, during the season of Pope Day, John Han-

cock made a dramatic public statement. Samuel

Adams had organized a “Union Feast” bringing

together members of the North and South End

gangs, with respectable politicians and merchants,

“with Heart and

Hand in owing

Bowls and bumping

Glasses.” John Han-

cock paid the tab

and never looked

back.

In 1758 young John Hancock signed

a merchants’ petition protesting

taxes. Notice the curlicues under the

signature. It is not yet the famous

version on the Declaration of

Independence but Hancock is work-

ing on it. Massachusetts Archives.

House of Hancock

His benefactions were many, including maintenance of Boston

Common, provision of fi rewood and food for the poor, and

donating Boston’s fi rst fi re engine. In the depressed economy of

1765 he offered loyal workers a chance to have their own branch

store under the name “House of Hancock” with a 50/50 profi t

sharing agreement. Four clerks accepted the offer. Possibly this

was America’s fi rst business franchise.

13

Repeal

“

The expectation of a rupture with the colonies...has

struck the people of Great Britain with more terror

than they ever felt for the Spanish Armada...It was this

terror...which rendered the repeal of the Stamp Act,

among the merchants at least, a popular measure.”

Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Cause

of the Wealth of Nations

The Merchants of London

At eleven o’clock on the morning of March

17, 1766 London merchants boarded y

coaches and traveled as a caravan to the

House of Lords. at morning they had ap-

proved a petition to King George III to accept

Parliament’s vote repealing the Stamp Act.

e following day the twenty-seven year old

king agreed. Reports of violent protest across

colonial America, the impossibility of un-

loading stamps, and the damaging boycott of

British goods had been decisive.

Celebration

News of repeal reached

Boston with the arrival

of the brigantine Harri-

son, on May 16th. London

merchants had sent word on one of John Hancock’s

ships. It was a piece of luck. Many thought that Han-

cock was responsible for repeal. Perhaps he thought

so himself. ere was universal rejoicing. Church bells

pealed, and guns red. John Hancock paid for re-

works on Boston Common and for the release of every

person in debtors’ prison. He set out casks of Madeira

wine in front of his Beacon Hill home.

An eighteenth century English coach.

Broadside announcing repeal

New York Historical Society

Afterword

e joy was short lived because Parliament quickly ap-

proved the Declaratory Act reiterating its right to tax

the colonies. e Stamp Act crisis was a beginning,

not an end. It de ned the issues that would lead to the

American Revolution, “taxation without representa-

tion” and the need for a democratic government that

would protect rights. During the crisis several gures

stepped out of the provincial shadows and onto the

historical stage. ey presented a world-view that is

still revolutionary today.

What’s in a word? Boycott

Samuel Adams used the term Non-Importation Agreement.

The word ‘boycott” originated in Ireland in 1880 when

tenant farmers used this strategy against estate agent

Charles C. Boycott to protest high rents.

An eighteenth century brigantine.