We Draw

the Lines!

Exploring redistricting, its connection to the

US Census, and its importance in maintaining

democracy in America.

An Inquiry lesson for

11

th

and 12

th

grade teachers:

Should voters choose the politicians or

should politicians choose the voters?

Acknowledgments

This lesson is the product of a collaborative partnership between the

Los Angeles County Office of Education and the Sacramento County Office of

Education.

Without the following individuals’ expertise and guidance, this document would not

have been possible:

Project Facilitation and Oversight

Los Angeles County Office of Education:

Michelle Herczog, Ed.D.

Coordinator III, History-Social Science

Sacramento County Office of Education:

Frank Pisi

Director, History-Social Science

Module Author:

Adam Wemmer

US History, AP US Government and Politics, Honors Economics

Pacifica High School, Garden Grove Unified School District

Instructor/Professor,

California State University, Long Beach

California Redistricting

CENSUS 2020

Shoul

d Voters Choose the Politicians or Should Politicians Choose the voters?

CA United States History and Geography Standards:

● 11.11: Students analyze the major social problems and domestic policy issues in

contemporary American society.

11.11.7. Explain how the federal, state, and local governments have responded to demographic and

social changes such as population shifts to the suburbs, racial concentrations in the cities, Frostbelt-to-

Sunbelt migration, international migration, decline of family farms, increases in out-of-wedlock births,

and drug abuse.

CA Principles of Democracy Standards

● 12.2: Students evaluate and take and defend positions on the scope and limits of rights and

obl

igations as democratic citizens, the relationships among them, and how they are secured.

○ 12.2 3. Discuss the individual’s legal obligations to obey the law, serve as a juror, and pay taxes.

○ 12.2. 4. Understand the obligations of civic-mindedness, including voting, being informed on civic

issues, volunteering and performing public service, and serving in the military or alternative service

.

● 12.5: Students summarize landmark U.S. Supreme Court in

terpretations of the Constitution

and its amendments.

○ 12.5.1. Understand the changing interpretations of the Bill of Rights over time, including interpretations

of the basic freedoms articulated in the First Amendment and the due process and equal-protection-of-

the law clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

● 12.6: Students evaluate issues regarding campaigns for national, state, and local elective

offices.

○ 12.6.4. Describe the means that citizens use to participate in the political process (e.g., voting,

campaigning, lobbying, filing a legal challenge, demonstrating, petitioning, picketing, running for political

office).

○ 12.6.5. Discuss the features of direct democracy in numerous states (e.g., the process of referendums,

re

call elections).

○ 12.6.6. Analyze trends in voter turnout; the causes and effects of reapportionment and redistricting, with

speci

al attention to spatial districting and the rights of minorities; and the function of the Electoral

College.

Common Core ELA Reading Literacy Standards:

● Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

○ 7. Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse formats and media, including visually and

quantitatively, as well as in words.

CA History/Social Science Analysis Skills:

● Chronological and Spatial Thinking

○ Students use a variety of maps and documents to interpret human movement, including patterns of

domestic and international migration, changing environmental preferences and settlement patterns, the

frictions that develop between population groups, and the diffusion of ideas, technological innovations,

and goods

CA Redistricting

1

Teacher Introduction:

“We the people” of the United States directly elect one member to the U.S. House of Representatives,

and each state is guaranteed at least one House member and two U.S. Senators. During the drafting of the

Constitution, the Great Compromise produced the current bicameral structure for the U.S. Congress, with

states equally represented in the Senate (with two senators regardless of population or geographical size),

while representation in the House would be allocated proportionally based on each state’s population. Because

of this arrangement, today larger states like California have significantly more representatives (53) compared

to states with smaller populations, such as Wyoming and Vermont, with just one representative each.

Determining each state’s representation in Congress is the main reason the federal government

conducts the Census, a nationwide population count that occurs every ten years as required by Article I,

Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution:

"Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States ... according to their

respective Numbers ... . The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first meeting of the

Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years."

The Census Bureau (an agency within the Department of Commerce) conducts the census by

counting all persons living in U.S. residential structures, including citizens, legal residents, long-term visitors,

and the undocumented. After the census is completed, important shifts in political and economic power occur.

States gaining population stand to gain power in presidential elections, per the Constitution’s Article II

Section 1 rule that electoral vote totals represent “the whole Number of Senators and Representatives” per

state. Given the constitutional power of the House to initiate revenue bills and impeachment proceedings, one

could also make the case that the population of each state amplifies Congress’s enumerated (stated)

powers. Furthermore, census data is used to determine the distribution of roughly $1.5 trillion dollars in yearly

federal funds, including federal grants-in-aid to the states for education, health care, and other income

security programs. States with bigger populations are generally eligible for more federal dollars, whereas

states with declining populations can lose federal money.

Since political and economic power are at stake with each census, both the methodology of the

census and the results are often contested. After the 1920 census, Congress failed to pass a

reapportionment act (which allocates changes in the number of House seats to the states) due to disputes

over whether urban populations had been properly counted. More recently, in 2018 the Trump administration

announced plans to include a citizenship question on the 2020 census, which had not been asked since

1950. California (and some other states) challenged this proposed question in federal court, arguing it was

designed to intimidate census participants, leading to inaccurate data on the size of the state’s population. An

undercount could cost California billions in federal dollars, but also seats in Congress, and with that fewer

electoral college votes in future presidential elections. With the 2020 census now completed, for the first time

in its history California is projected to lose a House seat and will be represented by 52 House members

beginning with the 2022 midterm Congressional elections.

CA Redistricting

2

Background on Redistricting:

The process of redistricting that follows the census, and the unique way California conducts this

process is the focus of this lesson. Article I Section IV of U.S. Constitution granted the Congress authority

for establishing federal rules on the “manner” of Congressional elections, but states are given the authority for

creating their own legislative boundaries following the census:

“The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in

each State by the Legislature thereof”

In 1929 Congress fixed the total number of House seats at 435, where it remains to this day. States

showing significant population increases after the census generally pick up seats in the House, whereas states

with declining populations (and even stable populations or minimal growth relative to other states) can lose

seats in the House. Therefore, Congressional elections, unlike those for the President and the Senate, involve

a process known as redistricting. After the 435 House seats are apportioned (allocated) to the states following

the census, the states have the responsibility for “mapping” or creating new legislative districts, and these

districts apply to Congressional and state level legislative races held over the next decade. In 2021, every

U.S. state will engage in a redistricting process that will be used in electoral contests starting in 2022.

On the surface, redistricting may appear to be a neutral process, but with the development of political

parties after the Constitution’s ratification, it did not take long for state level politicians to find ways to draw

districts for political ends. In 1812 Massachusetts Elbridge Gerry used his influence as governor to have his

state’s congressional districts redrawn to strengthen the Democratic-Republican party’s majority in the

legislature. One of the unusually shaped districts resembled a lizard, hence the emergence of the term

“gerrymandering”. This particular district, and the controversies surrounding gerrymandering, are featured in

this lesson.

Supreme Court rulings also set guidelines states must respect during the redistricting process,

including protections against malapportionment, the creation of unequally sized districts and/or using

discriminatory practices in creating districts. During the civil rights movement, the Supreme Court spoke to

this controversy, by ruling that the 14

th

Amendment’s “equal protection” clause required states use similar

sized populations in districts to protect the “one person, one vote” principle [see Baker v. Carr (1962) and

Reynolds v. Sims (1964)]. These rulings halted racially discriminatory practices such as creating districts

with smaller numbers of whites alongside districts with larger numbers of African Americans, effectively

diluting the voting power of the state’s Black population. Today all legislative districts (both state legislatures

and congress) must have roughly the same amount of people to ensure citizens are equally represented. With

our nation’s population growth, today each House district represents roughly 711,000 persons, and state level

legislative districts must be equal in population size to the others in that state.

Supreme Court rulings on redistricting also involve the role of the federal Voting Rights Act (1965).

Intended to eliminate Jim Crow era voting restrictions such as literacy tests, by 1990 the focus of the Voting

Rights Act was it’s enforcement provisions and whether “majority-minority” districts would be permitted.

These were districts with equal populations, but where concentrations of minority populations (usually African

American) were concentrated. In Shaw v. Reno (1993) and again in Miller v. Johnson (1999), the Supreme

court ruled that gerrymandering based solely on racial data (so-called “racial gerrymandering”) was

unconstitutional. In other words, race can be one factor in creating electoral districts, but it cannot be the sole

factor used in creating districts. Another provision of the Voting Rights Act that has come under scrutiny is

whether states with a history of voting discrimination (known as “covered jurisdictions”) should still be

required to submit plans to the U.S. Justice Department for “preclearance” before any changes in voting laws

can take effect. In Shelby County v. Holder (2012), the “preclearance” provision of the Voting Rights Act was

held to be outdated, which gave states more latitude in creating new voting laws and new district boundaries.

In Evenwel v. Abbott (2016), states were given discretion in defining the total population (including children,

prisoners, and non-citizens living within a district boundary) used in creating legislative boundaries.

CA Redistricting

3

Finally, in 2018 the Supreme Court looked at the issue of partisan gerrymandering - districts

deliberately drawn to advance the interests of one political party over the other. In Gill v. Whitford (2018) the

Court reviewed a gerrymandering plan initiated by the Republican legislature in Wisconsin, but ruled the

absence of a clear formula to determine what constitutes partisan gerrymandering meant (at this point) that no

constitutional violation was present. This does not mean controversies over partisan gerrymandering have

subsided, and the Court’s ruling suggested an openness to revisit this issue. This type of gerrymandering is

the focus of second part of this lesson, and ending partisan voter discrimination is the subject of several bills

in the current US Congress (including the Biden administrations proposed “For the People Act”)

In most states today redistricting is inherently a political process since state legislatures and the

governor are involved in creating and approving new electoral boundaries. Our current political environment

is also characterized by high rates of party-line voting (or “partisanship”) combined with historic rates of

negative polarization (negative views of the other party). This is partly why ¾ of US states are controlled by

just one party, with 23 states currently having Republican Party control of the legislature and the

governorship, and in 15 states the Democratic Party has control of both the executive branch and the

legislative branch. In almost every case, this makes the redistricting process even more intensely partisan, as

the majority party attempts to protect and gain political advantages by redrawing district lines to advance their

interests and please their voters. Computer mapmaking technology, access to voter registration records, and

the widespread availability of various other types of voter data has enabled the process to become even more

refined and perhaps even more partisan.

One reform proposed to address partisan gerrymandering (and its effects like party polarization and

congressional gridlock) is removing the power of redistricting from elected officials. After recent decades with

historic rates of incumbent re-election, and growing concerns about partisan voter discrimination, 13 U.S.

states now assign at least some responsibility for drawing election boundaries to redistricting commissions.

In those states either parts of the redistricting or the entirety of the redistricting process are removed from

elected officials, and usually public hearings and citizen involvement are part of the process. Like voting itself,

this is designed to give citizens more oversight and input into who represents them. In 2008, after a record

number of California incumbents (current officeholders) won re-election, California voters used the initiative

process to move redistricting for the state Assembly and the state Senate to an independent redistricting

commission. In 2010 this commission’s power was expanded by voters with another initiative to cover the

boundaries for congressional races in the state. The 2020 California Citizens Redistricting Commission -

its role, process, merits and drawbacks - is the subject of the second half of this lesson.

Whether redistricting is done by elected officials or by independent commissions, states set most of the

criteria for mapping legislative districts, subject to Supreme Court rulings and federal law. Criteria used by

states include contiguity (keeping areas within a district connected), compactness (keeping residents living

near each other together in districts), protecting communities of interest (keeping groups with a common

political, social, or economic interest together), and some states require keeping local political boundaries

(counties, cities, towns, etc.) together when creating legislative districts. While district lines are generally

required to be “contiguous” in most states, they are not necessarily required to be “compact” (geographically

concentrated), so some “gerrymandered” districts are only held together only by a single street and can stretch

for hundreds of miles. This is part of the reason the controversy over redistricting is likely to continue past

2020, and several of these districts are featured in this lesson.

2020 was certainly a pivotal election year in the U.S., with a presidential race, congressional elections,

and a national census all occurring simultaneously, something that occurs only once every 20 years! Now it

looks like 2021/2022 could be even more impactful, with the census data, 2020 election outcomes, and the

various types of state redistricting methods shaping the political landscape that will influence the next

generation of U.S. politics.

CA Redistricting

4

Student Vocabulary Terms

Reapportionment is the process of determining how many Congressional seats each state receives after the

U.S. census.

Redistricting is the actual redrawing of districts that is done within each state.

Gerrymandering is the manipulation of the redistricting process for political gain; this is also known as

partisan gerrymandering or partisan redistricting

incumbent: the current officeholder; “incumbency” refers to the power of office holders to retain their seats at

high rates, in part due to gerrymandering

safe-seat: legislative districts (Congressional or state legislature) without meaningful 2-party competition

Packing: Placing as many voters of one type in a district to minimize the number of elections they can

influence elsewhere (this contributes to voter “wastage”, a term critics of gerrymandering use to explain the

larger than normal and unnecessary margins of victory that are deliberately created in packed districts)

Cracking: Spreading voters of one type into multiple districts where they will comprise minority blocs less

likely to influence elections; like packing, it is another type of partisan gerrymandering, which critics see as a

modern form of voter discrimination.

gridlock: the inability of Congress to produce meaningful legislation due to excessive partisanship

party polarization: ideological divisions that contribute to partisan divisions in Congress; negative

polarization refers to negative feelings toward the other political party

Proposition 11 (2008): a.k.a. the “Voters First Act”, this proposition passed by voters in 2008 placed the

power to draw State Assembly and State Senate Districts in a Citizens Redistricting Commission, as opposed

to the state legislature

Proposition 20 (2010): known as “The Voters First Act for Congress”, this initiative extended the power to

draw electoral boundaries for the U.S. House of Representatives to the Citizens Redistricting Commission.

California Citizens Redistricting Commission: created after passage of Proposition 11, this 14 member

commission has responsibility for drawing state legislative district boundaries. The Commission is made up of

5 members of the Democratic Party, 5 members of the Republican Party, and 4 members of neither Party.

CA Redistricting

5

PART I. Anticipatory Set

What do you know about the U.S. census? Do you know how the census is connected to

representation in Congress?

PART II. An Introduction to Redistricting and Gerrymandering

A. Redistricting and the Census: After completion of the national census, states gaining population can gain

seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, while states losing population can lose seats in the House.

Congressional reapportionment is the process of redistributing House seats to reflect national population

changes. Since 1960, states with growing populations (mainly Sunbelt states in the South and Southwest)

have generally gained seats, while states with declining populations (mostly Midwestern and Northeastern

“Rustbelt” states) have generally lost seats. Use the map below for the following questions.

Congressional Reapportionment: 1960-2010

1. Which regions and states gained the most seats in Congress between 1960-2010?

2. Which US regions and states lost the most seats in Congress between 1960-2010?

3. In which direction did political representation shift from 1960-2010? What was the reason for this?

CA Redistricting

6

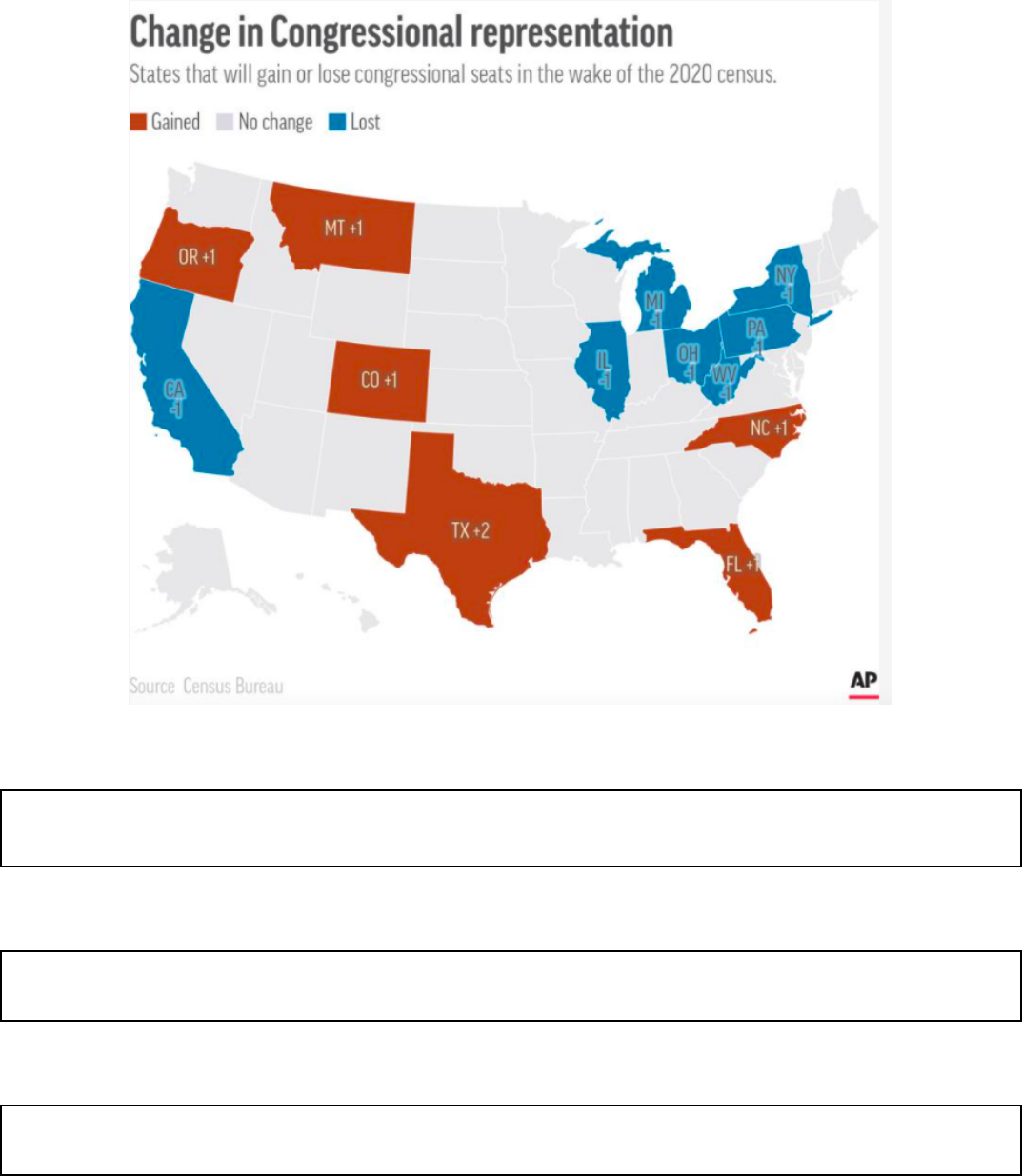

B. Reapportionment and the 2020 Census: The recently completed 2020 census will change the number of

Congressional seats allocated to certain U.S. states, and also the amount of electoral votes (a combination

of state’s total House members plus Senators) they will have in the 2024 presidential election . While most

states' total population increased from 2010-2020, only states significantly gaining or losing population relative

to other states see changes in the size of their Congressional delegation and electoral vote total (this is why

most states are “No change” in the map below). Use the map to answer the following questions:

1. Which states will gain representation in Congress following the 2020 census? Which states will lose at least

one Congressmen based on the 2020 census?

2. States gaining House seats also gain electoral votes in the 2024 presidential election. Why is that, and

which U.S. state benefited the most?

3. For the first time in its history, California is poised to lose a seat in the House. How does this fit with the

population trends you identified in Part A? How could losing representation in Congress affect California?

CA Redistricting

7

C. Gerrymandering: Election boundaries are redrawn by the states the year following the census, and they

are often designed to give advantages to incumbents (the current officeholders), especially from the party in

power in the state legislature. Many of these districts are drawn in unusual shapes for political purposes,

known as “gerrymandering,” in honor of a district created over 200 years ago to benefit Massachusetts

politician Elbridge Gerry. Since most states use partisan legislators (Democratic or Republican elected

officials) in redistricting, politicians have an incentive to design districts to help themselves and/or their party.

This leads to high rates of re-election in both the U.S. Congress and in U.S. state legislatures, which is one

reason most countries do not have elected officials involved in drawing their own election boundaries. Refer to

the political cartoon in the following questions.

1.What is gerrymandering and why do state officials

gerrymander districts?

2. Why do you think most countries avoid having

politicians create legislative district boundaries?

This political cartoon, drawn by Elkanah Tisdale in 1812,

shows a Massachusetts legislative district drawn to benefit

Elbridge Gerry looking similar to a salamander. This was done

to boost the political fortune of Gerry and the Democratic Party

in the state.

CA Redistricting

8

D. Packing and Cracking: Sometimes during the redistricting process the majority party will intentionally

create a district or districts “packed” with voters of the other party. This shows that gerrymandering is not just

about creating comfortable seats for the majority party, but also to give the opposite party as few of those as

possible. After the 2010 census, some Republican (or G.O.P.) controlled states created Democratic-leaning

African American Congressional districts. While this virtually guarantees a “safe-seat” for a Democrat, by

concentrating Democratic support in fewer locations across the state it increases the likelihood that outlying

districts will elect Republicans by spreading more G.O.P voters into the other districts. Use the map below of

North Carolina’s 13 Congressional districts created after the 2010 census, with its 3 black-majority districts

(NC-1, NC-4 and NC-12) for the next questions:

1. Using the top map in the image above, why would the Republican controlled legislature in North Carolina

create three Democratically leaning “safe seats”?

2. In 2012 the three “packed” districts in North Carolina all elected Democrats, with all 10 other districts in the

state electing Republicans; this despite Democrats winning 50.6% of total House votes statewide in 2012.

According to the bottom two state maps in the image above, what would happen if Democrats controlled the

redistricting process? What if an independent, or non-partisan, commission controlled the state’s redistricting?

3. Some of these “packed” districts in North Carolina stretch hundreds of miles around geographically

disconnected African American communities. Why might this be another problem with gerrymandering?

CA Redistricting

9

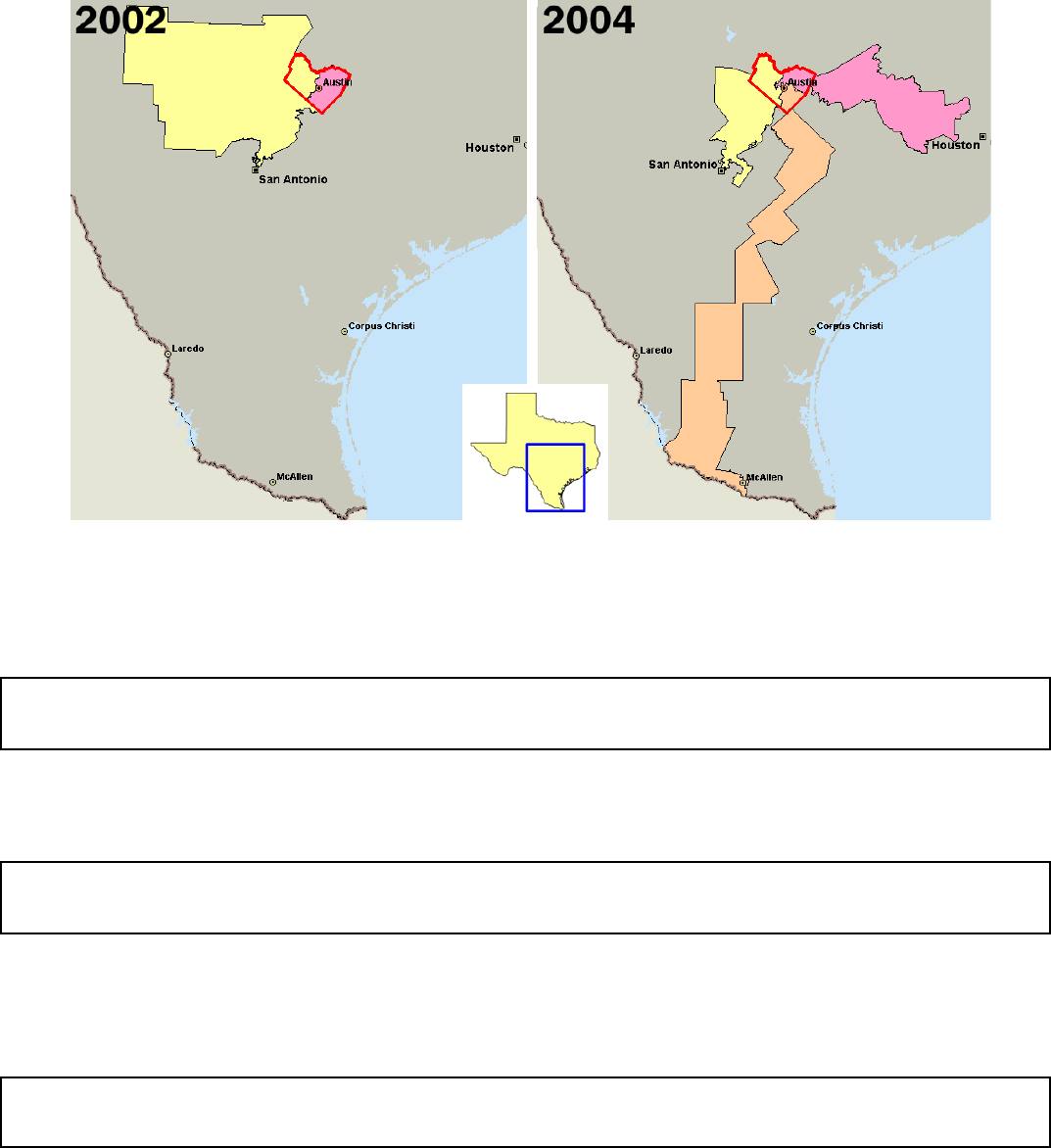

Cracking is the other major type of partisan or party based gerrymandering. With computer mapping

technology and greater access to voter information databases, it is easier than ever for determined state

policymakers to create partisan districts. Since the 1990s, several states have effectively produced districts

across the entire state without meaningful 2-Party competition. In 2004 a redistricting plan in Texas led to

intense court battles after the Republican controlled legislature redrew several Congressional boundaries to

increase the size of the states’ G.O.P. delegation. By “cracking” a district that encompassed the Democratic

leaning city of Austin, lawmakers were able to divide this community into 3 new districts. Republican

candidates won each of these 3 districts in the next election. Use the map below for the next questions:

U.S. congressional district covering Austin and parts of Travis County, Texas (outlined in red) in 2002, left, and 2004,

right. After the 2004 Republican redistricting plan took effect, the voting power of the Democratic residents of the

district was diluted by distributing its residents among three new majority-Republican districts.

3. What happened to the residents in the Democratic leaning district in the Austin area after the 2004 Texas

redistricting plan took effect?

4. In 2002,

2 years before the Republican redistricting plan took effect, Texas Democrats won 17 of the 32 House

seats, or 53% of the total in the state, despite Republicans winning the statewide congressional vote 53% – 44%.

What does this suggest Democrats did when they controlled redistricting in Texas?

5. As a result of party-based redistricting, Congressional Quarterly estimates that less than a quarter of the

435 House seats are competitive (elections where the Democratic and the Republican candidates are within

10% of each other in the election results). With most districts now “safe seats” for incumbents, winning

candidates typically receive over 60% of the vote. How are both packing and cracking connected to this?

CA Redistricting

10

E. Political and Economic Consequences: David Daley, Senior Fellow at electoral reform group FairVote,

documented some of the impacts of partisan redistricting after the 2010 census. Following low Democratic

voter turnout and frustration with President Barack Obama, Republicans won 700 new state legislative seats

that year. This allowed the GOP to control the redistricting process in states representing 193 House districts

(or 44% of the 435 total House seats). In 2012, the first election using these newly drawn districts, Democratic

candidates won 1.4 million more popular votes nationwide than Republicans, but the G.O.P. came away with

33 more House seats. In seven states where Republicans gained control of both the legislature and the

governorship in 2010, they received 16.7 million votes to the Democrats 16.4 million votes in 2012, and in

these seven states Republicans won 73 of the 107 House seats.

1. In the seven states mentioned above, Republican candidates received a slight majority of the

statewide vote in Congressional races (50.4% to 49.6%) but won 68% of the House seats in those

states. In that same 2012 election cycle, a similar pattern was seen in states with Democratic Party

control over redistricting. In Maryland, for example, Democrats won a slight majority of the statewide

popular vote but won 7 of the 8 House seats in the state. How can we explain both major U.S. political

parties winning seats in Congress far in excess to their popular vote percentages?

In 2010 Republicans came to power at the state level in Pennsylvania and gained the power to redraw the

state's Congressional districts. In 2012 Pennsylvania Democratic House candidates won 83,000 more votes

than Republican House candidates statewide (or 50.5% of the total), but Republicans won 13 seats to the

Democrats 5 seats. One district drew attention for its unusual shape, the 7th district outside Philadelphia, also

known as the “Donald Duck kicking Goofy” district. Use the two maps below for the next question

Pennsylvania’s 2012 Congressional map, with 5 Democratic districts (Blue), and 13 Republican districts (Red), and its

infamous 7th district outside Philadelphia, aka the “Donald Duck kicking Goofy” district. The 7th was rated as the 4th most

gerrymandered district in the US by the Washington Post given its lack of compactness and geographical spacing.

2. What is a concern with partisan gerrymandering represented by each map above?

CA Redistricting

11

Gerrymandering can also be problematic from a governing standpoint. By increasing the geographical

distance of a district, it can be harder for legislators to know their constituents compared to a legislator from a

more compact or “contiguous” district. More so, if a legislative district is concentrated with voters of one

party, those districts' representatives will likely govern in a more partisan or ideological manner, which can

perpetuate Congressional gridlock (the inability to reach the compromise needed to pass laws). In the 2013

federal budget shutdown, many Republican legislators who voted to continue the shutdown represented

heavily conservative leaning, mostly white districts. Similarly, in districts composed mainly of African American

voters, the “left of center” Democrats who represented these districts generally opposed cuts in federal

spending. Both divisions played a role in perpetuating the budget stalemate.

3. In terms of the ability to govern effectively, identify one problem associated with gerrymandering.

Then, identify a positive outcome more competitive Congressional races might bring.

Scholars also cite gerrymandering as a leading cause of growing polarization in Congress. In gerrymandered

districts the real competition is often the primary election to represent the party in the November general

election. In districts without meaningful 2 party competition, the winner of the primary is almost guaranteed to

win the November general election. This has led to a new term, “getting primaried”, where a

Congressperson with an ideology or record seen as too moderate is targeted for defeat by groups both

outside and inside the party (often backed by millionaires and billionaires who contribute money to

SuperPACs who can fund issue ads and campaign mailers urging their defeat).

4. How might gerrymandering also contribute to growing levels of political polarization in Congress?

Evidence also suggests allowing partisan mapmakers to create districts gives them an incentive to include or

exclude wealthy interests. In Detroit, Michigan’s 14th district (largely African American and working class), the

new General Motors plant and Faygo Soda headquarters - where many of 14th’s residents work - are drawn

outside the 14th district’s boundaries. Instead, these headquarters are included in the wealthier and whiter

surrounding district. According to FairVotes David Daley, this means “there will be no easy campaign cash

and no famous constituency for the member of Congress from the 14th.” Similarly, the old Detroit Tigers

baseball stadium and the vacant Silverdome (where the NFL’s Detroit Lions used to play) are drawn inside

the 14th district, while the new Ford Field (where the Lion’s currently play) and the new Comerica Park (where

the Tiger’s now play) are drawn outside the 14th district despite being walking distance from most points

inside the 14th district. This leads to less tax revenue coming into the 14th district as well.

5. What economic consequences may also exist with partisan gerrymandering?

CA Redistricting

12

-

-

-

-

III. Reforms

A. Two Approaches to Redistricting: Imagine a U.S. state with 30 people in it: 12 are gold party members

and 18 are blue party members. How might you divide these people into 3 equally populated voting districts

with 10 voters each?

Sample State District Map #1: In the first example blue party representation is maximized by placing 6 blue

voters with 4 gold voters, yielding 3 blue representatives.

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

1. In Sample State District Map #1, each of the districts has ten people, but the blue party wins all three

seats (or 100% of the representation possible) with only 60% of the eligible voters. What do we call

this type of redistricting?

State District Map #2: Now create 3 equally populated districts that maximize Gold party representation.

Remember, you need 10 squares per district, the squares must connect, and number the squares 1-3 to show

where you placed blue and yellow voters (hint: you should be able to make 2 yellow districts and 1 blue

district using the same data, and “yellow” voting district 1 is done for you)

1- Gold

1- Gold

1 Blue

1 Blue

Blue

1- Gold

1- Gold

1 Blue

Blue

Blue

1- Gold

1 - Gold

1 Blue

Blue

Blue

Gold

Gold

Blue

Blue

Blue

Gold

Gold

Blue

Blue

Blue

Gold

Gold

Blue

Blue

Blue

2. In State District map #2, what technique(s) did you use to maximize Gold Party representation?

CA Redistricting

13

Now draw the most competitive districts you can using the same voter data.

State District Map #3

Gold

Gold

Blue

Blue

Blue

Gold

Gold

Blue

Blue

Blue

Gold

Gold

Blue

Blue

Blue

Gold

Gold

Blue

Blue

Blue

Gold

Gold

Blue

Blue

Blue

Gold

Gold

Blue

Blue

Blue

3. How many seats did the blue party win in this map? How many did the Gold Party win? How does this

compare to the outcomes in Sample Map #1 and State District Map #2?

B. Taking Informed Action:!"#$!%&'%!(#)*+,!-%)./,.!0,11(2'3.,1/30!'3.!-,,3!&#$!,'-(!/%!/-!%#!.#4!/%*-!%/2,!

5#1!(#)!%#!%'6,!/35#12,.!'7%/#38!9'36!%&,!5'7%#1-!:,;#$!51#2!<=!>!/3!%,12-!#5!$&/7&!-&#);.!:,!?1/#1/%/@,.!/3!

71,'%/30!;,0/-;'%/+,!./-%1/7%-!A<!:,/30!%&,!2#-%!/2?#1%'3%!5'7%#1!'3.!>!:,/30!%&,!;,'-%!/2?#1%'3%B8

_____ Keeping county/city boundaries together inside districts

_____ Compactness/geographical size of the district (not stretching hundreds of miles if possible)

_____ Keeping “communities of interest” together in districts (racial, economic, cultural, religious, etc.)

_____ Contiguity (keeping areas within districts connected to each other)

_____ Partisanship/party affiliation of the voters in the district (the most common factor currently used)

1. Briefly explain your rankings. Did they align with how most states conduct redistricting?

CA Redistricting

14

C. Should Gerrymandering end? A growing number of politicians in both parties have come to believe that

gerrymandering should be ended. Use the quotes below for the next question:

“Most estimates are that, of the 435 House seats, fewer than 50 are genuinely competitive. Most members

now sitting in House seats know that the outcome of the next election in their district will be in the favor of

their party or the other. In other words, you can predict the party outcome now because of the way

redistricting has occurred. The Republicans have been most successful at this, the last time around for

redistricting, because they controlled more State legislatures after the 2010 election, the last Census year.

Democrats, in the past, did much the same...We all know that in our country we have an embarrassingly

low level of participation in elections... This gives hugely disproportionate influence to the most activist, the

most ideological, the most rigid, and the most uncompromising persons in their parties, on both sides....”

- George Mitchell, former Democratic Senator from Maine, 2013

“Gerrymandering is about politicians picking the voters rather than the voters picking the

politicians...They've gotten so smart with the technology to know exactly how to draw the district lines so

that they get the perfect Democratic district and the perfect Republican district. You now have to now be so

far to the left to win the Democratic district, and so far to the right to win a Republican district, that when

they go to work and get to the Capitol and try to work together, they can't.”

- Arnold Schwarzenegger, former Republican Governor of CA, 2017

1. What are some of the different reasons Democrat George Mitchell and Republican Arnold

Schwarzenegger give for ending partisan gerrymandering?

2. Several U.S. states have already removed at least some of the power to draw election boundaries

from elected officials. The U.S. Congress is also seriously considering legislation that would place new

federal regulations on gerrymandering. Yet, many who have concerns about gerrymandering also feel

it should not be the job of the federal government to tell the states how to create their election

boundaries. This means a variety of reform proposals, including:

● Putting term limits on members of Congress to reduce high incumbency rates

● Establishing uniform federal criteria for states to use in creating their districts

(compactness, contiguity, keeping “communities of interest” together, etc.)

● Having state Independent Redistricting Commissions create legislative boundaries

At this point, which of these reforms would you favor and why? Which would you oppose and why?

CA Redistricting

15

D. California’s Independent Redistricting Commission: Some states - including California - now use

independent redistricting commissions to create their legislative districts. As of 2017, however, only 13 states

(including Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, New Jersey, and Washington) use this process. In November

2008, California voters passed Proposition 11, authorizing the creation of the Independent Citizens

Redistricting Commission to draw state legislative district lines, taking the job out of the hands of the

California Legislature, and transferring it to the citizens. In 2010, the VOTERS FIRST Act added the

responsibility of drawing Congressional districts to the Commission. This commission now draws the 120

state legislative districts (80 for the State Assembly, 40 for the State Senate) as well as California’s U.S.

Congressional districts.

1. What did CA voters decide in 2008 and in 2010 regarding the issue of redistricting? Did their choice

match any of your preferences in the question before this?

The 2020 Citizens Redistricting Commission: Every ten years, after the federal government publishes

census information, California must redraw the boundaries of its Congressional, State Senate, and State

Assembly districts. The Voters FIRST Act authorized the creation of an independent Commission of 14

members, which include five Democrats, five Republicans, and four who are either registered without, or

“independent” of, any political party other than the Democrats and Republicans. For approval, new district

boundaries need votes from three commissioners of the largest party, three from the second largest, and three

of the commissioners from neither party. You may refer to https://www.wedrawthelinesca.org/ for additional

information about the redistricting process underway in California.

2. How are citizens and different political party members involved in California’s redistricting process?

Competitiveness: Studies by the Public Policy Institute of California and Ballotpedia show that California now

has some of the most competitive districts in the nation, creating opportunities for new elected officials

. In the

event that voters did not like the maps drawn by the commission, the maps may be overturned by public

referendum (a public vote), and in the event that a map is overturned, the California Supreme Court appoints a

new group of voters to create a new map. The California Constitution also now requires that districts be

contiguous, and mandates that "[districts] must ... preserve the geographic integrity of cities, counties,

neighborhoods and communities of interest." Districts must also "encourage compactness”, with State Senate

and Assembly districts nested within each other where possible. (All About Redistricting, 2015)

3. Review your informed action criteria from the question in Part II above. Do any of the criteria used in

California match your top rankings? What does the research on election competitiveness suggest

about California’s approach?

CA Redistricting

16

.

4. Using the infographic above, what are some of the ways citizens can directly participate in California’s

redistricting process?

CA Redistricting

17

E. Defining Community: Finally, the California Citizens’ Redistricting Commission conducts a series of public

meetings after the commissioners are selected, allowing voters up and down the state to review how they

define “community” in their area, offer suggestions to the Commission on how to “draw their community” into

legislative district maps, and offer testimonials (either written and in-person) to the Commissioners. Here is

an example of a testimony taken from the website of the Commission (https://www.wedrawthelinesca.org/)

I live in an area called Oak Knoll Valley. The neighborhood is bounded between Highway 9 on the

west and Sunnyside River on the east side. There are approximately 8,000 residents in Oak Knoll

Valley and it is primarily a residential area with some areas zoned for commercial and mixed use

especially along the river.

The languages spoken in Oak Knoll Valley are primarily English and Spanish with some residents

speaking Vietnamese and Mandarin. While most residents go outside our community for shopping and

employment, they tend to stay here for their socializing, religious activities, and recreation. The Oak

Knoll Regional Center provides a variety of activities and is a real hub of the community.

Across the river is the town of River Glen which is like our community as it is mostly residential. We

are in the same school district and the high school which Oak Knoll students attend is in River Glen. It

would make sense that we would be included in the same legislative or Congressional district.

On the other side of Highway 9 is Gold City which is primarily an industrial and commercial area. Most

of the residents live in multi--

-

family apartment buildings and many of them are new to the area. Gold

City is part of a different school district than Oak Knoll. While Gold City is in close proximity to Oak

Knoll, we have less in common than we do with River Glen.

1. How would you define your “community” to the Commission? Does it extend beyond the city

boundaries as the voter above suggests?

2. What if California did not have an independent redistricting commission, and elected officials divided

your community for partisan political purposes? Now revisit the initial question in the lesson, “Should

Voters Choose their Politicians or Should Politicians Choose their voters?

3. Raise your voice! Now that you’ve learned about redistricting and have identified your community, visit

www.drawmycacommunity.org to let the California Citizens Redistricting Commission know about YOUR

Communities of Interest!

CA Redistricting

18

●

EXTENSION ACTIVITY: What do the actual Congressional districts look like in our state? What about a

neighboring state? Use GovTrack to help see what they look like and answer the questions that follow:

Are all the

districts in your

state similar in

shape?

Do you notice

any

irregularities?

Are any districts

more oddly

shaped than

others?

Other

Observations

Resources

● Congressional Quarterly/CQ Roll Call (info.cq.com)

● We Draw the Lines CA (wedrawthelines.ca.gov/)

● FairVote (www.fairvote.org/)

● All About Redistricting (redistricting.lls.edu/)

● McGhee, Eric; Krimm, Daniel (September 2012). "Test-driving California's Election Reforms". Public

Policy Institute of California.

● Hrabe, John (July 18, 2012). "10 California U.S. House races ranked 'most competitive' in country".

CalWatchdog.

● King, Tyler (Aug. 16, 2012). "2012 competitiveness in California state legislative elections". Ballotpedia

● Ingraham, Christopher (May 15, 2014) “America’s most gerrymandered districts” Washington Post

● Click Here for the six criteria that the California Citizens Redistricting Commission must consider

when drawing lines.

CA Redistricting

19