Working Paper No. 698

$29,000,000,000,000: A Detailed Look at the Fed’s Bailout by Funding Facility

and Recipient

by

James Felkerson

University of Missouri–Kansas City

December 2011

The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by

Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to

disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals.

Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit,

nonpartisan, independently funded research organization devoted to public service.

Through scholarship and economic research it generates viable, effective public policy

responses to important economic problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in

the United States and abroad.

Levy Economics Institute

P.O. Box 5000

Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-5000

http://www.levyinstitute.org

Copyright © Levy Economics Institute 2011 All rights reserved

1

ABSTRACT

There have been a number of estimates of the total amount of funding provided by the Federal

Reserve to bail out the financial system. For example, Bloomberg recently claimed that the

cumulative commitment by the Fed (this includes asset purchases plus lending) was $7.77

trillion. As part of the Ford Foundation project “A Research and Policy Dialogue Project on

Improving Governance of the Government Safety Net in Financial Crisis,” Nicola Matthews and

James Felkerson have undertaken an examination of the data on the Fed’s bailout of the

financial system—the most comprehensive investigation of the raw data to date. This working

paper is the first in a series that will report the results of this investigation.

The extraordinary scope and magnitude of the recent financial crisis of 2007–09 required

an extraordinary response by the Fed in the fulfillment of its lender-of-last-resort function. The

purpose of this paper is to provide a descriptive account of the Fed’s response to the recent

financial crisis. It begins with a brief summary of the methodology, then outlines the

unconventional facilities and programs aimed at stabilizing the existing financial structure. The

paper concludes with a summary of the scope and magnitude of the Fed’s crisis response. The

bottom line: a Federal Reserve bailout commitment in excess of $29 trillion.

Keywords: Global Financial Crisis; Fed Bailout; Lender of Last Resort; Term Auction Facility;

Central Bank Liquidity Swaps; Single Tranche Open Market Operation; Term Securities

Lending Facility and Term Options Program; Maiden Lane; Primary Dealer Credit Facility;

Asset-backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility; Commercial

Paper Funding Facility; Term Asset-backed Securities Loan Facility; Agency Mortgage-backed

Security Purchase Program; AIG Revolving Credit Facility; AIG Securities Borrowing Facility

JEL Classifications: E58, E65, G01

2

INTRODUCTION

There have been a number of estimates of the total amount of funding provided by the Federal

Reserve to bail out the financial system. While the Fed at first refused to provide data on its

bailout, the Congress—led by Senator Bernie Sanders—ordered the Fed to provide an

accounting of its actions. Further, Bloomberg successfully pursued a Freedom of Information

Act suit for release of detailed data. That resulted in a “dump” of 25,000 pages of raw data.

Bloomberg has recently claimed that the cumulative “spending” by the Fed (this includes asset

purchases plus lending) was $7.77 trillion. However, the reports have not been sufficiently

detailed to determine exactly what was included in that total.

We have conducted the most comprehensive investigation of the raw data to date. We

find that the total spending is actually over $29 trillion. This is the first of a series of working

papers in which we will present our results. We hope that other researchers will compare these

results with their own, and are providing detailed break-downs to aid in such comparisons.

The extraordinary scope and magnitude of the recent financial crisis of 2007-2009

required an extraordinary response by the Fed in the fulfillment of its lender of last resort

function (LOLR). The Fed’s response did not disappoint; it was truly extraordinary. The

purpose of this paper is to provide a descriptive account of the Fed’s response to the recent

financial crisis. In an attempt to stabilize financial markets during the worst financial crisis since

the Great Crash of 1929, the Fed engaged in loans, guarantees, and outright purchases of

financial assets that were not only unprecedented (and of questionable legality), but

cumulatively amounted to over twice current U.S. gross domestic product. The purpose of this

paper is to delineate the essential characteristics and logistical specifics of the veritable

“alphabet soup” of LOLR machinery rolled out to save the world financial system. We begin by

making a brief statement regarding the methodology adopted in developing a suitable method

with which to measure the scope and magnitude of the Fed’s crisis response. The core of the

paper will follow, outlining the unconventional facilities and programs aimed at stabilizing (or

“saving”) the existing financial structure. Only facilities in which transactions were conducted

are considered in the discussion (some facilities were created but never used). The paper will

conclude with a summary of the scope and magnitude of the Fed’s crisis response. In later

working papers we will continue to provide more detailed analysis of the spending.

3

METHODOLOGY

The explicit objective of LOLR operations is to halt the initiation and propagation of financial

instability through the provision of liquidity to individual financial institutions or financial

markets; or both. At any given moment in time, the available supply of ultimate liquidity is

determined by the actions of the Fed and the U.S. Treasury. As the LOLR to solvent financial

institutions, the Fed has traditionally found it satisfactory to accomplish its LOLR responsibility

through conventional channels. The conventional tools are threefold. When acting as the LOLR,

the Fed can increase the availability of liquidity by lending directly to institutions through the

discount window; transactions of this nature are conducted at the initiative of participants. It can

also make the terms upon which it lends to institutions more generous by decreasing the rate it

charges for borrowing or lengthening the repayment period for loans. In recent years, however,

preoccupation with control of the money stock has shifted emphasis from measures conducted at

the initiative of the borrower to those undertaken at the initiative of the Fed. This new line of

thinking holds that the provision of liquidity in times of crisis should be executed through the

medium of open market operations. This line of thought argues that the market mechanism will

efficiently allocate liquidity to those who have the greatest need during times of heightened

demand. And so this third method has come to dominate in Fed actions.

In response to the gathering financial storm, the Fed acted quickly and aggressively

through conventional means by slashing the federal funds rate from a high of 5.25 percent in

August 2007 to effectively zero by December 2008. The Fed also decreased the spread between

its primary lending rate at the discount window and the federal funds rate to 50 basis points on

August 17, 2007, as well as extending the term from overnight to up to 30 days. On March 16,

2008, the Fed further reduced the spread to 25 basis points and extended terms up to 90 days.

However, the efficacy of the Fed’s conventional LOLR tools had little appreciable effect during

the initial stages of the recent financial crisis. Moreover, the period of moderation brought about

by such measures was of relatively short duration. These actions largely failed to ameliorate

rapidly worsening conditions in opaque markets for securitized products such as mortgage

backed securities (MBS).

In an attempt to counter the relative ineffectiveness of its conventional LOLR tools, the

Fed designed and implemented a host of unconventional measures, unprecedented in terms of

size or scope and of questionable legality. The goal of these unconventional measures was to

4

explicitly improve financial market conditions and, by improving the intermediation process, to

stabilize the U.S. economy as a whole. The authorization of many of these unconventional

measures would require the use of what was, until the recent crisis, an ostensibly archaic section

of the Federal Reserve Act—Section 13(3), which gave the Fed the authority “under unusual

and exigent circumstances” to extend credit to individuals, partnerships, and corporations.

1

In an attempt to halt growing financial instability, the Fed ballooned its balance sheet

from approximately $900 billion in September 2008 to over $2.8 trillion dollars as of today.

Figure 1 depicts the weekly composition of the asset side of the Fed’s balance sheet from

January 3, 2007 to November 10, 2011. As is clearly indicated in the graph, the Fed’s response

to events of that fateful autumn of 2008 resulted in an enlargement of its balance sheet from

$905.6 billion in early September 2008 to $2,259 billion by the end of the year—an increase of

almost 150 percent in just three months! This initial spike in the size of the Fed’s balance sheet

reflects the coming online of a host of unconventional LOLR programs, and depicts the extent

to which the Fed intervened in financial markets. The graph also depicts the winding down of

unconventional tools starting in early 2009. However, the decrease was of short duration, as the

focus of the Fed shifted from liquidity provisioning to the purchase of long-term securities—

which, as of November 10, 2011, comprise approximately 85 percent of the Fed’s balance sheet.

Figure 2 shows the structure of Fed liabilities over the same period. Casual inspection of

the graph indicates the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet was accomplished entirely through

the issuance of reserve balances, creating liquidity for financial institutions.

Before moving on to an analysis of the characteristics of each of the facilities

implemented by the Fed in its bailout, a methodological note is in order. We have elected to

adopt a twofold approach to measuring the scale and magnitude of the Fed’s actions during and

since the financial crisis. The composition of the Fed’s balance sheet is expressed in terms of

stocks; that is, it reflects the Fed’s asset and liability portfolio at a moment in time. However,

the provision of liquidity in the form of reserves by the Fed in the purchase of assets manifests

itself as a flow. The outstanding balance of assets and liabilities held by the Fed adjust as

transactions are conducted. This is simply a definitional outcome of double-entry accounting.

When private sector economic units repay loans or engage in liquidity-absorbing transactions,

1

With the passage of Dodd Frank, the Fed must now make extraordinary crisis measures “broad based.” What

exactly “broad based” connotes remains to be seen.

5

the Fed’s balance sheet shrinks. Conversely, when private sector agents participate in liquidity-

increasing transactions with the Fed, the Fed’s balance sheet increases in size.

The changing composition and size of the Fed’s balance sheet offers great insight into

the scope of the Fed’s actions since the crisis. As new, unconventional programs were initiated,

they represented a new way for the Fed to intervene in the financial system. Furthermore, given

that many of the programs were specifically targeted at classes of financial institutions or

markets, and later at specific financial instruments, we are able to identify the markets or

individual financial institutions that the Fed deemed worthy of “saving.” To account for changes

in the composition of the Fed’s balance sheet as transactions occur and are settled, we shall

report two variables referencing the weekly influence of an unconventional facility on the

Figure 1 Fed Assets, in billions, 1/3/2002-9/28/2011

Source: Federal Reserve H.4.1 Weekly Statistical Release and other Fed Sources

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

3500

1/3/2007 1/3/2008 1/3/2009 1/3/2010 1/3/2011

Allothercategories

OtherAssets

CBLS

AIA/ALICO

MaidenLane's

CPFF

TALF

OtherCreditExtensions(includes

AIGRCF)

AMLF

6

Figure 2 Fed Liabilities, in billions, 1/3/2002-9/28/2008

Source: Federal Reserve H.4.1 Weekly Statistical Release and other Fed Sources

composition and size of the asset side of the Fed’s balance sheet: the weekly amount

outstanding (stock), and the weekly amount lent (flow). The amount outstanding adjusts due to

the repayment process, but fails to capture the entire picture. The whole image emerges when

we include the weekly amount lent. As will be seen, many of the unconventional actions taken

by the Fed were the result of a targeted response to a particularly traumatic event. Given that the

respective facilities reflect different terms of repayment, and that initial usage of a crisis facility

after an adverse shock was large, the amount outstanding will often increase to a high level and

remain there until transactions are unwound. This is captured by the aforementioned “spike” in

the Fed’s balance sheet. Considering the disparity between lending and repayment, special

emphasis will be placed on the peak dates for the amounts lent and outstanding since such time

periods were often associated with excessive turmoil in financial markets. However, this leaves

us with a dilemma: How are we to measure the magnitude of the Fed’s bailout?

Our attempt to capture the magnitude of the Fed’s bailout is informed by the idea that

when the Fed operates as LOLR, it interrupts the normal functioning of the market process

‐3500

‐3000

‐2500

‐2000

‐1500

‐1000

‐500

0

1/3/2007 1/3/2008 1/3/2009 1/3/2010 1/3/2011

TotalCapital

Otherliabilities

OtherDeposits

ForeignOfficialDeposits

SFA

TGA

Otherdepositsbydepository

institutions

TermDeposits

ReverseRepos

7

(Minsky 1986). To provide an account of the magnitude of the Fed’s bailout, we argue that each

unconventional transaction by the Fed represents an instance in which private markets were

incapable or unwilling to conduct normal intermediation and liquidity provisioning activities.

We exclude actions directed at the implementation of monetary policy, or what have been

identified as the conventional tools of LOLR operations. Thus, to report the magnitude of the

bailout, we have calculated cumulative totals by summing each transaction conducted by the

Fed. It is hoped that reference to the changing composition of the Fed’s balance sheet and

cumulative totals will present both a narrative regarding the scope of the Fed’s crisis response as

well as inform readers as to the sheer enormity of the Fed’s response.

To sum, there are three different measures which we will report; each of which is

important in capturing a different aspect of the bailout. First, there is the size of the Fed’s

balance sheet at a point in time—the total of its assets and liabilities. That tells us how much

ultimate liquidity the Fed has provided; it also gives some measure of the risks to the Fed (for

example, by looking at its stock of risky assets purchased from banks). Next, there is the flow of

lending over a period, as a new facility is created to deal with an immediate need for funds.

Spikes will indicate particular problems in the financial sector that required the Fed’s

intervention. Finally, there is the cumulative total of all the funds supplied by the Fed outside

“normal” monetary policy operations, which gives an idea of the scope of the impact of the

global financial crisis.

The Facilities (or the Big Bail)

Several times, the Fed has issued public statements arguing that its crisis response machinery

was implemented sequentially and consists of three distinct “Stages.” Each “Stage” can be

broadly viewed as a response to the evolution of the crisis as it proliferated through financial

markets. The characteristics of each facility within the different “Stages” were largely

conditioned by a more or less shared set of objectives.

2

The presentation of the Fed’s response

as sequential responding to events is useful for the categorization of the unconventional LOLR

operations. The rationale for and purpose of the programs initiated during the different “Stages”

is indeed chronologically associated with economic events. However, this approach has a major

shortcoming in that it does not take into account actions on the part of the Fed directed at

2

See Bernanke 2009 or Sarkar 2009 for an account of this classification scheme.

8

specific institutions. We have chosen to adopt the “Stages” approach due to its merit as a

narrative explaining the Fed’s response to major events over the course of the crisis, and

included the support provided by the Fed to specific institutions that occurred within the period

of time with which a “Stage” is identified. Within each “Stage,” we shall present the individual

facilities in chronological order.

Stage One: Short-Term Liquidity Provision

Crisis facilities associated with Stage One were addressed at the provision of short-term

liquidity to solvent banks and other depository institutions as well as to other financial

institutions (Bernanke 2009). Facilities mobilized under the auspices of Stage One were aimed

at “improving aggregate liquidity and also the distribution of liquidity across financial

intermediaries” (Sarkar 2009). Sarkar (2009) and Bernanke (2009) identify the objectives of the

Stage One facilities as being consistent within the intent of the Fed’s traditional LOLR mandate.

The Term Auction Facility (TAF) was announced on December 12, 2007. The TAF was

authorized under Section 10B of the FRA and was “designed to address elevated pressures in

short-term funding markets” (Federal Reserve 2007). Historically, depository institutions have

obtained short-term liquidity during times of market dislocation by borrowing from the discount

window or borrowing from other financial institutions. However, the “stigma” associated with

borrowing from the discount window led many depository institutions to seek funding in

financial markets.

3

Given pervasive concern regarding liquidity risk and credit risk, institutions

resorting to private markets were met with increasing borrowing costs, shortened terms, or

credit rationing. To address this situation, the TAF provided liquidity to depository institutions

via an auction format. The adoption of an auction format allowed banks to borrow as a group

and pledge a wider range of collateral than generally accepted at the discount window, thus

removing the resistance to borrowing associated with the “stigma problem.” Each auction was

for a fixed amount of funds with the rate determined by the auction process (Federal Reserve

2008a, p. 219). Initially, the auctions offered a total of $20 billion for 28-day terms. On July 30,

2008, the Fed began to alternate auctions on a biweekly basis between $75 billion, 28-day term

loans and $25 billion, 84-day credit. The TAF ran from December 20, 2007 to March 11, 2010.

3

It is believed by many, including the Fed, that discount window borrowing attaches a “stigma” to the borrower.

Evidence of its usage is often interpreted as a position of financial weakness, and may result in additional pressures

from creditors or inability to find counterparties.

9

Both foreign and domestic depository institutions participated in the program. A total of 416

unique banks borrowed from this facility. Table 1 presents the five largest borrowers in the

TAF. As for aggregate totals, 19 of the 25 largest borrowers were headquartered in foreign

countries. The top 25 banks, all of which borrowed in excess of $47 billion, comprised 72

percent of total TAF borrowing. Of the 416 unique participants, 92 percent borrowed more than

$10 billion. Of the $2,767 billion borrowed by the largest 25 participants, 69 percent ($1,909.3

billion) was borrowed by foreign institutions. The Fed loaned $3,818 billion in total over the

Table 1 Top Five TAF borrowers, in billions

Parent Company Total TAF

loans

Percent of total

Bank of America Corporation $260 7.3%

Barclays PLC (United Kingdom) 232 6.1

Royal Bank of Scotland Group PLC

(United Kingdom)

212 5.5

Bank of Scotland PLC (United

Kingdon)

Wells Fargo

181

154

4.7

4.2

Source: Federal Reserve and GAO

run of this program. As shown in Figure 3, peak monthly borrowing occurred in January 2009 at

$347 billion; while the peak amount outstanding was, in early March 2009, at approximately

$493 billion. The last auction held for this facility occurred on March 8, 2010 with loans

maturing on April, 8 2010. All loans are said to have been repaid in full, with interest, in

agreement with the terms of the facility.

10

Figure 3 TAF, weekly amounts outstanding and lent, in billions

Source: Federal Reserve

As an additional response to “pressures in short-term funding markets,” the Fed opened

up currency swap lines with foreign central banks called the Central Bank Liquidity Swap Lines

(CBLS) (Federal Reserve 2007). With the CBLS, two types of credit arrangements were created

under the authorization of Section 14 of the FRA. Dollar liquidity swaps were arrangements that

allowed foreign central banks to borrow dollars against a prearranged line of credit. The CBLS

are structured as a repo contract in which the borrowing central bank would sell to the Fed a

specified amount of its currency at the exchange rate prevailing in foreign exchange markets.

Simultaneously, the participating foreign central bank would agree to buy back its currency on a

specified date at the same exchange rate at a market-based rate of interest. The first swap lines

were set up in December 2007 with the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Swiss National

Bank (SNB). Over the course of the crisis, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) would

also open up liquidity swap lines with numerous other foreign central banks. The facility ran

0

100000

200000

300000

400000

500000

600000

AmountOutstanding

AmountLent

11

from December 2007 to February 2010 and issued a total of 569 loans.

4

Figure 4 presents the

percentage of total borrowing by foreign bank counterparties. Table 2 presents total borrowing

by each foreign central bank. Peak monthly lending occurred in October 2008 at $2.887 trillion.

Figure 5 shows the peak outstanding, reaching its high in December 2008 at $583.13 billion and

peak weekly lending occurring in mid October 2008 at $851.286 billion. In total, the Fed

Table 2 CBLS borrowing by foreign central bank, in billions

Borrower Total Borrower Total

European Central Bank $8,011.37 Sveriges Riksbank (Sweden) $67.2

Bank of England 918.83 Reserve Bank of Australia 53.175

Swiss National Bank 465.812 Bank of Korea (South Korea) 41.4

Bank of Japan 387.467 Norges Bank (Norway) 29.7

Danmarks Nationalbank

(Denmark)

72.788 Bank de Mexico 9.663

Source: Federal Reserve

lent $10,057.4 billion to foreign central banks over the course of this program as of September

28, 2011. Thus far, all transactions were repaid in full, in accordance with the terms of the swap

agreements.

4

It should be noted that on June 29, 2011, the Fed extension of the swap lines through August 1, 2012 (Federal

Reserve 2011a). As November 10, 2011, $1.96 billion remains outstanding.

12

Figure 4 Foreign central bank borrowing by percentage

Source: Federal Reserve

As it became apparent that existing conventional and nonconventional LOLR operations

were failing to adequately allocate liquidity, the Fed announced on March 7, 2008 that it would

conduct a series of term repurchase transactions (ST OMO) expected to total $100 billion. These

transactions were 28-day repo contracts in which primary dealers posted collateral eligible

under conventional open market operations. The Fed is authorized to engage in open market

transactions by Section 14 of the FRA, and such operations are to be considered a routine part of

the Fed’s operating toolkit. However, we have chosen to include these transactions as part of the

Fed’s unconventional LOLR response, since their explicit purpose was to provide direct

liquidity support to primary dealers. In 375 transactions, the Fed lent a total of $855 billion

dollars. Peak monthly transactions occurred in the months of July, September, and December

2008 at $100 billion, consistent with the level of lending the Fed had expected. As these

transactions were conducted on a schedule, the amount outstanding quickly peaked on April 30,

2008 at $80 billion and remained at that level until the facility was discontinued on December

30, 2008. All extant primary dealers participated. Of these 19 institutions, nine were

headquartered in foreign countries.

EuropeanCentral

Bank

80%

Bankof

England

9%

SwissNationalBank

4%

BankofJapan

4%

AllOthers

3%

13

Figure 5 CBLS weekly amounts lent and outstanding, in billions

Source: Federal Reserve

Table 3 presents the five largest program participants; all of which were foreign

institutions. Transactions conducted with the five largest participants would comprise 65 percent

of the program total. As indicated in Figure 6, 77 percent ($657.91 billion) of all transactions

were conducted with foreign-based institutions.

Table 3 Largest five ST OMO participants, in billions

Participant Total Percent of

total

Credit Suisse (Switzerland) $259.31 30.3%

Deutsche Bank (Germany) 101.03 11.8

BNP Paribas 96.5 11.3

RBS Securities (United Kingdom) 70.45 8.2

Barclays Capital (United Kingdom) 65.55 7.8

Source: Federal Reserve

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1400

1600

12/12/2007 12/12/2008 12/12/2009 12/12/2010

Amountoutstanding,inbillions

Amountlent,inbillions

14

To supplement the aid provided to investment banks through the ST OMO and address

widening spreads in repo markets that were having an adverse impact on the allocation of

liquidity, the Fed announced on March 11, 2008 that it would extend its Treasury lending

program to “promote liquidity in the financing markets for Treasury and other collateral and

thus to foster the functioning of financial markets more generally” (Federal Reserve 2008a).

This nonconventional expansion of a conventional program was named the Term Securities

Lending Facility (TSLF) and began conducting auctions on March 27, 2008.

5

The Fed instituted

a two-fold classification scheme for eligible collateral under the TSLF. Schedule 1 collateral

was identified as “federal agency debt, federal agency residential-mortgage-backed securities

(MBS), and non-agency AAA/Aaa-rated private-label residential MBS” (Federal Reserve

2008a). Schedule 2 included agency collateralized-mortgage obligations and AAA/Aaa-rate

commercial-mortgage-backed securities, in addition to Schedule 1 collateral. In addition to the

TSLF, the Fed announced the TSLF Options Program (TOP), to facilitate access to liquidity in

funding markets during periods of elevated stress, such as quarter-ends, on July 30, 2008. The

Figure 6 Single Tranche Open Market Operations percentage by country

Source: Federal Reserve

5

It needs to be noted that the Fed routinely engages in overnight lending of Treasury securities. Following the Fed's

lead, we include transaction undertaken as part of the TSLF as part of the Fed's crisis response.

Switzerland, 37%

France,11.3%

Germany,

11.8%

United Kingdom,

16.5%

Japan, >1%

United States,

22.9%

15

TOP allowed participants to purchase the right but not the obligation to borrow funds if it

became necessary. The TSLF and TOP facilities are important as they mark the first use by the

Fed of the powers given under Section 13(3) of the FRA.

Eighteen primary dealers participated in the TSLF program, while only 11 accessed the

TOP facility. Of the 18 participants that took part in the TSLF, TOP, or both, eight were foreign

institutions. Table 8 presents the five largest TSLF participants, while Figure 7 shows that 51

percent of total borrowing was undertaken by foreign-based institutions. Figure 8 indicates that

86 percent of total borrowing was done by the nine largest program participants. Figure 9 shows

Table 8 Five largest TSLF and TOP participants, in billions

Borrower Totals Borrower Total

Citigroup Global Markets $348 Credit Suisse (Switzerland) $261

RBS Securities Inc. (United

Kingdom)

291 Goldman, Sachs & Co. 225

Deutsche Bank Securities

(Germany)

277

Source: GAO and Federal Reserve

that the week ending September 10, 2008 was the largest in terms of lending ($110.848 billion)

and the week ending October 1 the peak for amount outstanding ($235.544 billion). The Fed

lent $1,940 billion through the TSLF and another $62.3 billion under TOP for a cumulative total

of $2.0057 trillion. All loans are said to have been repaid on time in full, with interest, within

the terms of the program.

16

Figure 7 TSLF/ TOP borrowing by country

Source: GAO

Figure 8 TSLF percentage by participants

Source: GAO

It is also during Stage One that the first instance of the Fed offering assistance to a

specific institution appears. Throughout early-to-mid March 2008, Bear Stearns was

experiencing severe liquidity funding problems as counterparties refused to enter into

transactions with it, even for assets of unquestionable quality. Problems in securing access to

liquidity resulted in Bear informing the Fed on March 13 that it would most likely have to file

UnitedStates

49%

UnitedKingdom

21%

Germany

12%

Switzerland

16%

France

2%

Citigroup

15%

CreditSuisse

11%

DeutscheBank

12%

GoldmanSachs

10%

MerrillLynch

8%

MorganStanley

5%

RBS

12%

UBS

5%

Barclays

8%

Allothers

14%

17

for bankruptcy the following day should it not receive an emergency loan. In an attempt to find

an alternative to the outright failure of Bear, negotiations began between representatives from

Figure 9 TSLF, weekly amounts lent and outstanding, in billions

Source: Federal Reserve

the Fed, Bear Stearns, and J.P. Morgan. The outcome of these negotiations was announced on

March 14, 2008 when the Fed Board of Governors voted to authorize the Federal Reserve Bank

of New York (FRBNY) to provide a $12.9 billion loan to Bear Stearns through J.P. Morgan

Chase against collateral consisting of $13.8 billion. This bridge loan was repaid on Monday,

March 17 with approximately $4 million in interest. This temporary measure allowed Bear to

continue to operate while courting potential buyers. On March 16, J.P. Morgan agreed to a

provisional merger with Bear Stearns. Subsequent negotiations formulated the structure of J.P.

Morgan’s acquisition of Bear Stearns. The purchase of Bear was accomplished when the

FRBNY ($28.82 billion) and J.P. Morgan ($1.15 billion) funded a special purpose vehicle

(SPV), Maiden Lane, LLC (ML I), which purchased Bear’s assets for the approximate market

value of $30 billion. Authorization to conduct the transaction was provided by Section 13(3) of

the FRA. Maiden Lane, LLC would repay its creditors, first the Fed and then J.P. Morgan, the

0

50

100

150

200

250

3/27/2008

4/27/2008

5/27/2008

6/27/2008

7/27/2008

8/27/2008

9/27/2008

10/27/2008

11/27/2008

12/27/2008

1/27/2009

2/27/2009

3/27/2009

4/27/2009

5/27/2009

6/27/2009

7/27/2009

Amountoutstanding,inbillions

Amountlent,inbillions

18

principal owed plus interest over ten years at the primary credit rate beginning in September

2010. The structure of the bridge loan and ML I represent one-time extensions of credit. As one-

time extensions of credit, the peak amount outstanding occurred at issuance of the loans.

As the Fed endeavored to prevent the disorderly failure of Bear Stearns over the

weekend of March 15

th

, it was also laying the groundwork for implementing a standing credit

facility to assist primary dealers. The Fed officially announced the Primary Dealer Credit

Facility (PDCF) on March 16, 2008 in an attempt to prevent the effects of the Bear Stearns

situation from disrupting markets. The PDCF would function essentially as a “discount window

for primary dealers” and provide a nonmarket source of liquidity that would ease strains in the

repo market (Adrian, Burke, and MacAndrews 2009). Authorized by Section 13(3) of the

Federal Reserve Act, the PDCF would lend reserves on an overnight basis to primary dealers at

their initiative. PDCF credit was secured by eligible collateral, with haircuts applied to provide

the Fed with a degree of protection from risk. Initial collateral accepted in transactions under the

PDCF were investment grade securities. Following the events in September of that year, eligible

collateral was extended to include all forms of securities normally used in private sector repo

transactions. In addition, the Fed approved loans to the United Kingdom-based subsidiaries of

Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, and Citigroup. The PDCF issued 1,376 loans

totaling $8,950.99 billion. Shown in Figure 10 below are the peak weekly amounts outstanding

and lent, occurring on September 26, 2008 at $146.57 billion and $728.643 billion respectively.

6

Table 9 lists the five largest borrowers from the PDCF. Figure 11 captures the heavy usage of

6

Since the PDCF issued overnight loans, Figure 10 should be read carefully. The amount outstanding reflects only

loans for one day, while the amount lent includes the total of loans for a week.

19

Figure 10 PDCF, weekly amounts lent and outstanding, in billions

Source: Federal Reserve

the PDCF by the largest borrowers. As the graph shows, the five largest borrowers account for

85 percent ($7,610 billion) of the total. Eight foreign primary dealers would participate in the

PDCF, borrowing just six percent of the total. The PDCF was closed on February 1, 2010. All

loans extended in this facility have been repaid in full, with interest, in agreement with the terms

of the facility.

Table 9 Five Largest PDCF borrowers, in billions

Borrower Total

Merrill Lynch $2,081.4

Citigroup 2,020,.2

Morgan Stanley 1,912.6

Bear Stearns 960.1

Bank of America 638.9

Source: Federal Reserve

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

Amountlent

Amountoutstanding

20

Figure 11 PDCF, borrowing by institution

Source: Federal Reserve

In its involvement with American Insurance Group (AIG), the Fed again acted as LOLR

to a specific institution. Confronted by the possibility of the voidance of millions of personal

and business insurance products, the Fed took steps to ensure AIG’s survival through several

targeted measures. To provide AIG with space to create a viable plan for restructuring, the Fed

provided AIG with a revolving credit facility (RCF) on September 16, 2008, which carried an

$85 billion credit line; the RCF lent $140.316 billion to AIG in total. To assist AIG’s domestic

insurance subsidiaries acquire liquidity through repo transactions, a securities borrowing facility

(SBF) was instituted. Cumulatively, the SBF lent $802.316 billion in direct credit in the form of

repos against AIG collateral. As a further step in addressing AIG’s problems maintaining

liquidity and staving off capital pressures, an SPV, Maiden Lane II, LLC (ML II), was created

with a $19.5 billion loan from the FRBNY to purchase residential MBS from AIG’s securities

lending portfolio. The proceeds received by AIG in the sale of its residential MBS portfolio

were used to repay the SBF and terminate that program. To address the greatest threat to AIG’s

restructuring—losses associated with the sizeable book of collateralized debt obligations

(CDOs) on which it had written credit default swaps (CDS)—another SPV, Maiden Lane III,

LLC (ML III), was funded by a FRBNY loan to purchase AIG’s CDO portfolio. The purchases

by ML III totaled $24.3 billion.

MerrillLynch,

23.3

Citigroup,22.6

Morgan

Stanley,21.4

BearStearns&

Co.,Inc.,10.7

Bancof

America

SecuritiesLLC,

7.1

Goldman,Sachs

&Co.,6.6

BarclaysCapital

Inc.,4.6

Allothers,3.8

21

As part of AIG’s divestiture program, the Fed conducted transactions on December 1,

2009 in which the FRBNY received preferred interests in two SPVs created to hold the

outstanding common stock of AIG’s largest foreign insurance subsidiaries, American

International Assurance Company (AIA) and American Life Insurance Company (ALICO). On

September 30, 2010 an agreement was reached between the AIG, the Fed, the U.S. Treasury,

and the SPV trustees regarding the AIA/ALICO transactions to facilitate the repayment of

AIG’s outstanding obligations to the United States government. AIG, the Treasury, and the

FRBNY announced the closing of the recapitalization plan announced on September 30, 2010,

and all monies owed to the RCF were repaid in full January 2011. Section 13(3) of the FRA was

invoked to conduct each facility providing AIG direct assistance. Table 10 lists the specific total

dollar amount for facilities providing AIG with assistance and the amount outstanding as of

November 10, 2011.

Table 10 Facilities providing AIG with assistance, in billions

Facility Total Amount outstanding as of

11/10/2011

RCF $140.316 $0

SBF 802.316 0

Maiden Lane II 19.5 9.336

Maiden Lane III 24.3 18.049

Preferred Interests in AIA/ ALICO 25 0

Source: Federal Reserve

Stage Two: Restart the Flow of Credit by Direct Purchases of Assets

The second stage of actions taken by the Fed represent an even larger departure from

conventional LOLR operations when the Fed, in an attempt to circumvent the inability (or

unwillingness) of financial institutions to engage in the intermediation process, chose to extend

loans directly to support what were viewed as critical credit markets. The goal of the Fed in this

stage of the bailout was to restart the flow of credit to households and businesses by buying

assets in exchange for the most risk-free and liquid of assets—reserves.

The Fed’s first foray into supporting key credit markets occurred in the aftermath of

Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy. On September 1, 2008, the Reserve Primary Fund, the oldest

money market mutual fund (MMMF) in the U.S., lowered its share price below $1 and “broke

the buck.” As a response to the uncertainty regarding the value of positions in MMMFs,

investors scrambled to withdraw funds. During the week of September 15, investors withdrew

22

$349 billion. The total withdrawn in the following three weeks amounted to an additional $85

billion (Financial Crisis Inquiry Comission 2011, p. 357). To meet withdrawal requests, many

mutual funds were forced to sell assets, triggering increased downward pressure on asset prices.

The creation of the AMLF was an attempt to forestall the liquidation of assets by funds, and

therefore prevent further deflation in asset prices. The Fed responded to this series of events

with a facility targeting the MMMF market.

The Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility

(AMLF) was designed to extend nonrecourse loans to intermediary borrowers at the primary

credit rate. On the same day the AMLF loan was issued, intermediaries used these funds to

purchase high quality asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) issued by MMMFs. The indirect

process adopted was necessitated by “statutory and fund-specific limitations,” which prevented

the MMMFs from borrowing directly from the Fed. The primary intention of the AMLF was to

allow MMMFs to fund themselves by issuing ABCP to be purchased by intermediaries, with the

larger goal of the program being to provide liquidity in the broader money markets (Federal

Reserve 2009a, p. 53). The AMLF was announced on September 19, 2008 and executed by the

Federal Reserve Bank of Boston (FRBB). All loans were fully collateralized and borrowers and

intermediaries were subject to eligibility requirements. To ensure that the AMLF was being

used in accordance with its stated purpose, the Fed would later require MMMFs to provide

proof of material outflows prior to selling ABCP under the AMLF program (Federal Reserve

2009b). The authorization for the AMLF program would again come from Section 13(3) of the

FRA.

Two institutions, J.P. Morgan Chase and State Street Bank and Trust Company,

constituted 92 percent of AMLF intermediary borrowing; see Table 11. Over the course of the

program, the Fed would lend a total of $217.435 billion. As can be seen in Figure 12, peak

weekly lending and amount outstanding reached their apex on the week of Sepember 25, 2008

at $88.6 and $152.1 billion on October 2, 2008 respectively. The nine largest sellers of ABCP

are listed in Table 12. Funds

23

Table 11 AMLF buyers of ABCP, in billions

Parent Company Total AMLF

borrowing

Percent of

total

J.P. Morgan Chase $114.4 51.3%

State Street Bank and Trust Company 89.2 41.1

Bank of New York Mellon 12.9 5.9

Bank of America 1.6 0.7

Citigroup 1.4 0.7

Source: Federal Reserve

Figure 12 AMLF, weekly amounts lent and outstanding, in billions

Source: Federal Reserve

selling in excess of $10 billion comprised roughly 58 percent of overall ABCP sales. All loans

are said to have been repaid in full, with interest, in agreement with the terms of the facility. The

AMLF was closed on February 1, 2010.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

Amountoutstanding,inbillions

Amountlent,inbillions

24

Table 12 Nine largest sellers of ABCP under AMLF program, in billions

Fund Family Seller Total AMLF

sales

Percent of

Total

Reserve Funds $19 8.9%

J.P. Morgan Chase 18 8.1

Dreyfus 17 7.6

Columbia Funds 15 6.9

Barclays 13 5.9

Wells Fargo 12 5.6

BlackRock 12 5.5

Federated 10 4.7

Morgan Stanley 10 4.4

All others 92.01 42.4

Source: Federal Reserve

Despite providing support to the MMMFs through the AMLF so as to prevent

redemption requests from having a disruptive effect on debt markets, MMMFs showed little

inclination to resume their purchases of commercial paper (CP). Uncertain about counterparty

credit risk and their own liquidity risk, MMMFs shifted their portfolios toward more secure

assets, such as U.S. Treasuries (Anderson and Gascon 2009). As a consequence of the “flight to

safety” by market participants, credit markets essentially “froze up,” stalling the flow of credit

to households and businesses. To address this disruption, the Fed announced the Commercial

Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) on October 7, 2008. This facility was authorized under Section

13(3) of the FRA and was designed to improve liquidity in CP markets. The program was

structured to operate through an SPV since the CPFF’s logistics fell outside the Fed’s traditional

operating framework. The SPV provided assistance by purchasing highly rated ABCP and

unsecured U.S. dollar-denominated CP of three month maturity from eligible issuers. To

manage credit risk the Fed attached fees to program participation, collecting $849 million from

program participants, according to the Fed’s website.

A total of 120 unique institutions took part in this facility. The top ten borrowers (each

borrowing in excess of $20 billion) account for 64.3 percent ($473.9 billion) of all borrowing—

see Table 13 and Figure 13. The cumulative total lent under the CPFF was $737.07 billion. Peak

lending occurred during the first week of operations at $144.59 billion, and the largest amount

outstanding occurred on January 22, 2009 at $348.176 billion; see Figure 14. The CPFF was

suspended on February 1, 2010 and all loans are said be paid in full under the terms and

conditions of the program.

25

Table 13 Top ten CPFF borrowers, in billions

Borrower ABCP Unsecured CP Issuer total Percent of

CPFF total

UBS (Switzerland) $0.0 $74.5 $74.5 10.1%

AIG 36.0 24.0 60.2 8.2

Dexia SA (Belgium) 0.0 53.5 53.5 7.3

Hudson Castle 53.3 0 53.3 7.2

BSN Holdings (United Kingdom) 42.8 0.0 42.8 5.8

The Liberty Hampshire Company 41.4 0 41.4 5.6

Barclays PLC (United Kingdom) 0.0 38.8 38.8 5.3

Royal Bank of Scotland Group

(United Kingdom)

24.8 13.7 38.5 5.2

Fortis Bank SA/NV 26.9 11.6 38.5 5.2

Citigroup 12.8 19.9 32.7 4.3

Source: Federal Reserve

Figure 13 CPFF borrowing by institution

Source: GAO

Despite the CPFF and AMLF being implemented to improve conditions in credit

markets, pervasive uncertainty resulted in rising credit standards. At the time, it was believed

that upwards of 70 percent of banks tightened standards (Federal Reserve 2009c, p. 8). Financial

innovation in the credit intermediation process over the 20 years preceding the crisis had

resulted in the development of an “originate and distribute” model in which pools of loans were

packaged by lenders and sold as fixed income products. The sale of securitized ABS products

UBS

10%

AIG

8%

Dexia

SA

7%

HudsonCastle

7%

BSNHoldings

6%

TheLiberty

Hampshire

Company

6%

BarclaysPLC

5%

RoyalBankof

ScotlandGroup

5%

FortisBankSA

5%

Citigroup

5%

Allothers

36%

26

allowed lenders to move long-term (and illiquid) loans off their balance sheets and, in the

process, collect immediate profits and funding with which to make new loans. To confront

gridlock in ABS markets, and to increase the flow of credit throughout the U.S. economy, the

Fed announced the creation of the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) on

November 25, 2008. Operating similarly to the AMLF, the Fed provided nonrecourse loans to

eligible borrowers posting eligible collateral, but for terms of five years. Borrowers then would

act as an intermediary, using the TALF loans to purchase ABS. These ABS were required to

have received a credit rating in the highest investment-grade category by two approved ratings

agencies and would serve as collateral for the TALF loan. The ABS categories eligible for

issuance under the TALF included: auto loans, student loans, credit card loans, equipment loans,

“floor-plan” loans, insurance premium finance loans, small business loans fully guaranteed by

the U.S. Small Business Association, servicing advance receivables, and commercial mortgage

loans. Authorization to conduct the TALF was provided under Section 13(3) of the FRA.

Figure 14 CPFF weekly amounts lent and outstanding, in billions

Source: Federal Reserve

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

10/23/2008

11/23/2008

12/23/2008

1/23/2009

2/23/2009

3/23/2009

4/23/2009

5/23/2009

6/23/2009

7/23/2009

8/23/2009

9/23/2009

10/23/2009

11/23/2009

12/23/2009

1/23/2010

2/23/2010

3/23/2010

Amountoutstanding,inbillions

Amountlent,inbillions

27

Although the Fed terminated lending under the TALF on June 30, 2010, loans remain

outstanding under the program until March 30, 2015. The Fed loaned in total $71.09 billion

through this program. Significantly smaller in size than other emergency lending programs, the

TALF’s peak in terms of amount lent occurred the weeks beginning June 4, 2009 at $10.72

billion, and after suspending operations, the amount outstanding peaked at $48.19 billion on

March 18, 2010; see Figure 15. Of the total 177 borrowers, those borrowing over $2 billion

constituted 58 percent ($41.24 billion) of total borrowing; see Figure 16. The top five largest

borrowers are depicted in Table 14, and comprise 41.7 ($29.6) percent of total borrowing.

Figure 17 presents the allocation of TALF loans by asset category. As of November 10, 2011,

almost 15 percent of loans ($10.571billion) remain outstanding. No collateral has yet to be

surrendered due to default on payments.

Table 14 Top five TALF borrowers, in billions

Borrower Total

Morgan Stanley $9.3

PIMCO 7.3

CalPERS 5.4

Arrowpoint Capital 4.0

Angelo Gordon & Co. 3.7

Source: GAO

Figure 15 TALF weekly amounts lent and outstanding, in billions

Source: Federal Reserve

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

3/19/2009 3/19/2010 3/19/2011

Amountoutstanding,in

billions

Amountlent,inbillions

28

Figure 16 TALF borrowing by institution

Source: GAO and Federal Reserve

Stage Three: Purchases of Long-term Securities

The final stage of the Fed’s bailout is composed of the purchase of long-term securities in an

attempt to support the functioning of credit markets (Bernanke 2009). Policy actions associated

with this stage are the purchase of agency MBS and subsequent rounds of Quantitative Easing;

the latter of which, while unconventional, is well-known to monetary policy theory and in

practice, most noticeably by the example afforded by the Bank of Japan’s monetary policy

Figure 17 TALF lending by asset category, percentage and total, in billions

Source: Federal Reserve

Morgan

Stanley

13%

PIMCO

10%

CalPERS

8%

ArrowpointCapital

6%

AngeloGordon

andCo.

5%

Metropolitian

WestAsset

Management,LLC

4%

Belstar

Group

4%

WexfordCapital

4%

BlackRock

4%

Allothers

42%

Auto,12.79

Commercial

Mortgage,

12.07

CreditCard,

26.31

Equipment,

1.61

Floorplan,3.89

Premium

Finance,1.98

Servicing

Advances,1.31

SmallBusiness,

2.15

StudentLoan,

8.97

29

from the 1990s onward. Stage Three programs involve the “expansion of traditional open

market operations support to the functioning of credit markets through the purchase of long-

term securities for the Fed's portfolio” (Federal Reserve 2011b). Operations falling under this

stage consist of the purchase of two types of medium- and-long-term securities: agency MBS

and U.S. Treasury securities. As the purchase of Treasuries represents a weapon from the

monetary policy arsenal, and therefore is not associated with LOLR operations, we will consider

only the Fed’s purchase of MBS in this section.

The Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) facility was authorized by Section 14

of the FRA. It was created to stabilize the price of MBS, as well as to “increase the availability

for credit for the purchase of houses, which in turn should support housing markets and foster

improved conditions in financial markets more generally” (Federal Reserve 2008b). As of July

2010, the Fed purchased some $1,850.14 billion in MBS via open market operations conducted

by the FRBNY. However, as the Fed was making purchases, it was simultaneously conducting

sales—with net MBS purchases by the Fed at $1,250 billion. Figure 18 indicates that the Fed’s

MBS holdings peaked at $1,128.67 billion on June 23, 2010. The highest weekly purchases

occurred for the week beginning April 12, 2009, when the Fed made gross purchases of $80.5

billion. All transactions were conducted with primary dealers for MBS of three maturities: 15,

20, and 30 years—with the purchase of 30-year MBS comprising 95 percent of total purchases.

Table 15 presents the top five sellers of MBS to the Fed. Figure 19 shows that the top 5 sellers

accounted for 61.0 percent ($1.145) of total MBS purchases. Of the 16 program participants, the

9 foreign primary dealers constituted over half (52 percent) or $964.53 trillion of MBS sellers.

This relationship is expressed in Figure 20.

Table 15 Top five sellers to MBS program, in billions

Seller Total

Deutsche Bank Securities $293.325

Credit Suisse 287.26

Morgan Stanley 205.71

Citigroup 184.95

Merrill Lynch 173.57

Source: Federal Reserve

30

Figure 18 Weekly MBS purchases and amounts outstanding, in billions

Source: Federal Reserve

Figure 19 Sales to MBS program by institution, in billions

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

12/31/2008 12/31/2009 12/31/2010

Amountheld,inbillions

Amountpurchased,inbillions

DeutscheBank

16%

CreditSuisse

15%

MorganStanley&

Co

11%

Merril

Lynch

10%

Citigroup

9%

GoldmanSachs&

Co.

9%

J.P.Morgan

8%

BarclaysCapital

7%

UBS

5%

BNPParibas

4%

Allothers

6%

31

Source: Federal Reserve

Figure 20 MBS percentages purchases by country

Source: Federal Reserve

SUMMARY

When all individual transactions are summed across all unconventional LOLR facilities, the Fed

spent a total of $29,616.4 billion dollars! Note this includes direct lending plus asset purchases.

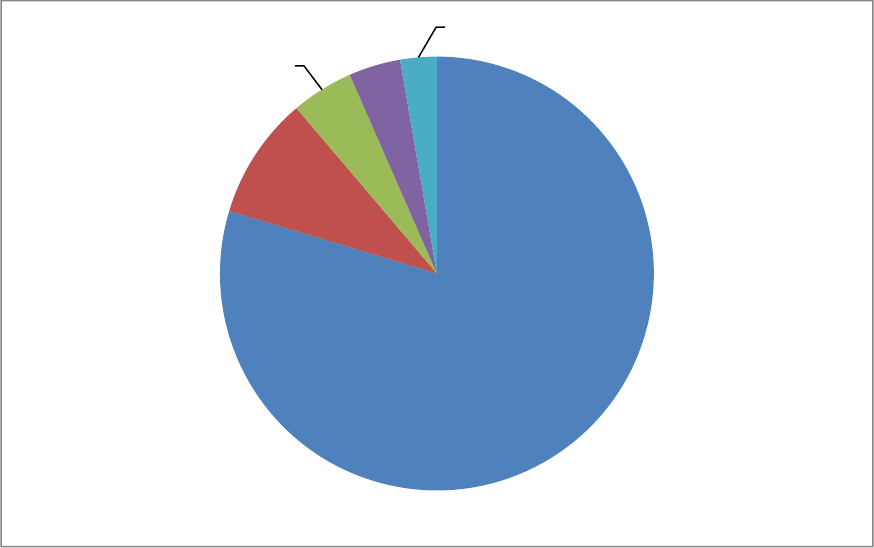

Table 16 and Figure 21 depict the cumulative amounts for all facilities; any amount outstanding

as of November 10, 2011 is in parentheses below the total in Table 16. Three facilities—CBLS,

PDCF, and TAF—would overshadow all other unconventional LOLR programs, and make up

71.1 percent ($22,826.8 billion) of all assistance.

Germany

16%

Switzerland

20%

UnitedKingdom

10%

France

4%

Canada

0%

Japan

2%

UnitedStates

48%

32

Table 16 Cumulative facility totals, in billions

Facility Total Percent of

total

Term Auction Facility $3,818.41 12.89%

Central Bank Liquidity Swaps 10,057.4

(1.96)

33.96

Single Tranche Open Market Operation 855 2.89

Terms Securities Lending Facility and Term Options

Program

2,005.7 6.77

Bear Stearns Bridge Loan 12.9 0.04

Maiden Lane I 28.82

(12.98)

0.10

Primary Dealer Credit Facility 8,950.99 30.22

Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual

Fund Liquidity Facility

217.45 0.73

Commercial Paper Funding Facility 737.07 2.49

Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility 71.09

(10.57)

0.24

Agency Mortgage-Backed Security Purchase Program 1,850.14

(849.26)

6.25

AIG Revolving Credit Facility 140.316 0.47

AIG Securities Borrowing Facility 802.316 2.71

Maiden Lane II 19.5

(9.33)

0.07

Maiden Lane III 24.3

(18.15)

0.08

AIA/ ALICO 25 0.08

Totals $29,616.4 100.0%

Source: Federal Reserve

Figure 21 Facility percentage of bailout total

Source: Federal Reserve

The cumulative total for individual institutions provides even more support for the claim

that the Fed’s response to the crisis was truly a bailout (of unprecedented proportions) and was

TAF

13%

CBLS

34%

STOMO

3%

TSLF/TOP

7%

BearStearns

(Bridge

Loan,MLI)

<1%

PDCF

30%

AMLF

1%

CPFF

3%

TALF

<1%

MBS

6%

AIG(RCF,

SBF,MLII,

MLIII,

AIA/ALICO)

3%

33

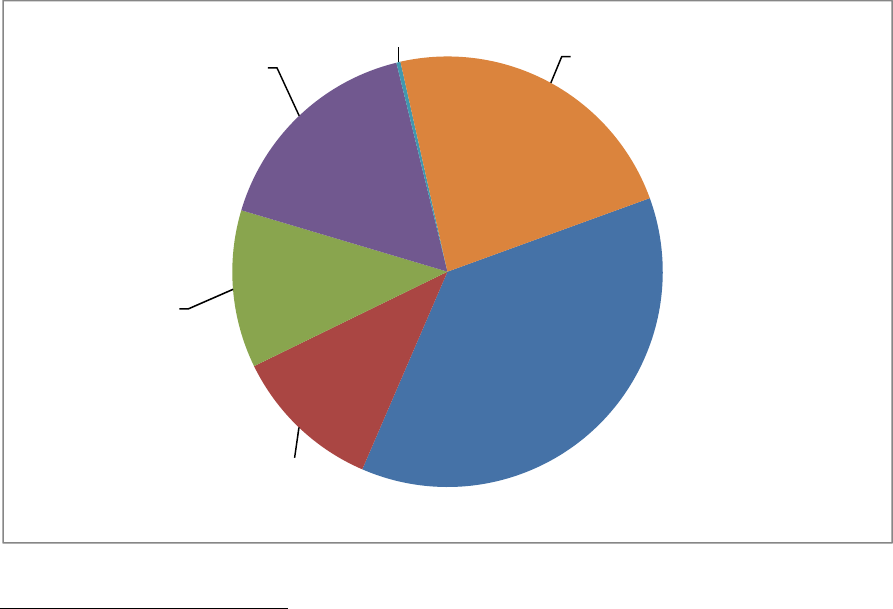

targeted at the largest financial institutions in the world. If the CBLS are excluded, 83.9 percent

($16.41 trillion) of all assistance would be provided to only 14 institutions. Table 17 and Figure

22 display the degree to which a few Too Big To Fail institutions received the preponderance of

support from the Fed. We note in passing that the six largest foreign-based institutions would

receive 36 percent ($10.66 trillion) of the total bailout.

Table 17 14 largest participants (excluding CBLS), in billions

Participant Total Percentage of

total

Citigroup $2,654.0 13.6%

Merrill Lynch 2,429.4 12.4

Morgan Stanley 2,274.3 11.6

AIG 1,046.7 5.4

Barclays (UK) 1,030.1 5.3

Bank of America 1,017.7 5.2

BNP Paribas (France) 1,002.2 5.1

Goldman Sachs 995.2 5.1

Bear Stearns 975.5 5.0

Credit Suisse (Switzerland) 772.8 4.0

Deutsche Bank (Germany) 711.0 3.6

RBS (UK) 628.4 3.2

JP Morgan Chase 456.9 2.3

UBS (Switzerland) 425.5 2.2

All others 3,139.3 16.1

Totals $19,559.00 100%

Source: Federal Reserve

Figure 23 Total participation by institution, excluding CBLS, in billons

Source: Federal Reserve

UBSAG

(Switzerland)

2%

RBS

(UK)

3%

MorganStanley

12%

MerrillLynch

13%

JPMorgan

Chase

2%

GoldmanSachs

5%

DeutscheBank

AG(Germany)

4%

CreditSuisse

(Switzerland)

4%

Citigroup

14%

BNPParibas

(France)

5%

BearStearns

5%

Barclays(UK)

5%

BankofAmerica

5%

AIG

5%

Allothers

16%

34

CONCLUSION

The Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 is remarkable for a number of reasons. On one hand,

it represents the explosion of the idealistic vision of efficient financial markets in which

financial innovation and deregulation had conquered the eternal bugbear of financial instability,

and resulted in a golden age called the “Great Moderation.” On the other hand, it exposed the

lengths to which central banks worldwide—the Fed being perhaps the best example—would act

to save the existing financial order, helping to preserve especially the largest and most powerful

institutions. We will never know what might have happened had there not been such a strong

intervention. The best we can do is study the methods through which central banks prevented

what surely would have been financial Armageddon. This short paper makes a first attempt at

doing just that.

This is the first of what we intend to be a series of working papers on the Fed’s bailout.

In this one, we have focused on an accounting of the funds spent, by facility. We have also

tallied how much the largest institutions received. Finally, we have indicated where foreign

institutions have received substantial help, including both foreign central banks as well as

private banks. In subsequent papers we will provide more detail on some of the Fed’s actions,

and will also discuss implications concerning such matters as risks to the Fed and Treasury of

losses due to the Fed’s expenditures, as well as matters related to Congressional oversight and

accountability of the Fed.

35

REFERENCES

Adrian, T., Christopher R. Burke, and James J. McAndrews. 2009. “The Federal Reserve’s

Primary Dealer Credit Facility.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Current Issues

15(4):1-10.

Anderson, R.G. and Charles S. Gascon. 2009. “The Commercial Paper Market, the Fed, and the

2007-2009 Financial Crisis.” The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 91(6):589-

612.

Bernanke, B.S. 2009. “The Crisis and the Policy Response.” Speech at the Stamp Lecture,

London School of Economics, London, England, January 13, 2009.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2009. 95

th

Annual Report.

Federal Reserve. 2007. “Federal Reserve Actions.” Federal Reserve press release, December

12, 2007.

________. 2008a. “Federal Reserve Actions.” Federal Reserve monetary policy release, March

11, 2008.

________. 2008b. Federal Reserve monetary policy release, November 25, 2011.

________. 2009a. 95

th

Annual Report. June 2009.

________. 2009b. Federal Reserve monetary policy release, January 30, 2009.

________. 2009c. The January 2009 Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending

Practices. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

________. 2011a. Federal Reserve monetary policy release, June 29, 2011.

________. 2011b. “Credit and Liquidity Papers and the Balance Sheet.” Federal Reserve

Monetary Palicy, November 4, 2011.

Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. 2011. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report.

Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office.

Minsky, H.P. 2008. Stabilizing An Unstable Economy. McGraw-Hill Inc. Originally published

1986.

Sarkar, Asani. 2009. Liquidity Risk, Credit Risk, and the Federal Reserve’s Response to the

Crisis. Staff Report 389, Federal Reserve Bank of New York.