Oregon Health Authority

Pharmacy Benefit Managers

Poor Accountability and

Transparency Harm

Medicaid Patients and

Independent Pharmacies

August 2023

Report 2023-25

November 8, 2023 - An update to this

report can be found in footnote twenty

on page 16.

Billions of dollars are spent on Medicaid. It is important the state take steps to ensure the program is run

efficiently and effectively to better serve people in Oregon. The current structure lacks transparency and is too

complex to efficiently measure value. The State should change the current model and enact legislation that

focuses on patient protections, pharmacy protections, and increasing transparency in the prescription drug supply

chain. Making these changes will help ensure the Medicaid program is getting good value for pharmacy benefits,

people have access to the same medications, and Oregonians have access to community pharmacies.

Why this audit is important

•

Prescription drugs reduce the need

for medical services and improve and

extend life. While efforts to lower

drug prices have targeted

manufacturers, there is growing

interest in reviewing the influence of

pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs).

•

The largest PBMs in the U.S. control

80% of the market share and are

vertically integrated with the largest

health insurance companies and

pharmacies. Vertical integration

poses risks to drug affordability and

decreases access to medications.

•

CCO patients do not have access to

the same medications under the

current model. Moving to another

CCO could result in patients needing

to go through the burdensome prior

authorization process.

•

Adopting leading practices will

improve pharmacy access, improve

transparency in the prescription drug

process, and potentially save

taxpayer dollars.

What we found

1. The current structure of Medicaid PBMs is too complex for the State

of Oregon to efficiently measure value

. The prescription drug process

in Medicaid involves multiple entities including sixteen CCOs

(Coordinated Care Organizations), six PBMs, hundreds of

pharmacies,

multiple drug manufacturers, wholesalers, pharmacy administrative

organizations, OHA, and the Department of Consumer and Business

Services, among others. (pg.

6)

2. Oregon’s regulation of PBMs is limited and fragmented. Other states

have meaningful legislation targeted at patient protections,

pharmacy protections, and transparency. PBM reforms are bipartisan

policy efforts to limit unfair practices, which can hurt community

pharmacies and limit access for people. Other states are also

adopting different PBM models for Medicaid, making it easier for

governments to provide effective oversight. (pg.

14)

3. Pharmacy reimbursements vary significantly depending on the

drugs,

pharmacy type, and PBM. Pharmacies often lose money when filling

certain prescriptions. We found that national chains, some of which

are owned by PBMs or PBM parent companies, were reimbursed

twice the amount independent pharmacies were for selected drugs.

(pg.

20)

4. OHA does not ensure sufficient transparency and compliance from

PBMs. While OHA has improved CCO contract language, more needs

to be done to ensure high-

risk areas are monitored appropriately and

contract provisions are comprehensive. (pg. 28)

rebate

Audit Highlights

Oregon Health Authority, Pharmacy Benefit Managers

Poor Accountability and Transparency Harm Medicaid Patients and

Independent Pharmacies

What we recommend

We made 2 recommendations to OHA and 7 to the Legislature. OHA agreed with all of our recommendations. The

response can be found at the end of the report.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 1

Introduction

Prescription drugs reduce the need for medical services and improve and extend life. The ever-

increasing cost of prescription drugs in the U.S. is a topic of national interest. The high price of

medications can reduce consumers’ access and contributes to higher spending, straining both state and

federal budgets. From 2009 to 2018, national spending on prescription drugs in the Medicaid program

increased from $18 billion to $32 billion.

The prescription drug system in the U.S. is complex, involving many entities. While some of the efforts

to decrease drug prices in recent years have targeted drug manufacturers, there is growing public

interest in assessing the role, value of, and significant power and influence held by third-party

organizations known as pharmacy benefit managers.

Pharmacy benefit managers are influential within the U.S. health care

system

The supply of prescription drugs starts with drug manufacturers, who develop and manufacture

medications. Some of the largest drug manufacturers in the world include Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly,

Pfizer, and AbbVie. Drug manufacturers then sell medications to wholesale distributors, who resell

those drugs directly to pharmacies or collective groups who pool resources and negotiate on their

behalf.

1

The final step in the supply chain happens when pharmacies fill and dispense medications to

consumers.

Involved in many of these processes are third-party companies known as pharmacy benefit managers

(PBMs). Today’s PBMs have emerged as powerful intermediaries between insurers, manufacturers,

pharmacies, and governments, though historically they were created as simple claims processing

administrators. Within this paradigm, the three largest PBM’s control 80% of the U.S. prescription

market as seen in Figure 1.

Private sector insurers first started covering high volumes of prescription drugs for health plans in the

1960s. When this happened, insurers had challenges in managing the overall increase in claims. Early

PBMs were initially created to ease the administrative burden of insurers. Over time, the role of PBMs

has expanded significantly.

In the decades after their initial creation, PBMs leveraged new technologies as they emerged to

streamline and simplify administrative processes, like creating real-time electronic claims processing

and efficient pharmacy communication methods. PBMs also began to offer new services over time to

insurers, like mail order, pharmacy networks, and clinical consulting, among others. In the 90’s, drug

manufacturers began acquiring PBMs, which created conflict of interest concerns. The Federal Trade

Commission ordered the manufacturers to divest the businesses and started a trend of mergers and

acquisitions within the PBM industry. Some of the current responsibilities of PBMs include:

• Processing and paying prescription drug claims;

1

The term collective groups is used in this report to refer to the combination of pharmacy services administration organizations

and group purchasing organizations. A definition of these entities, as well as a full glossary of terms, can be found in Appendix A.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 2

• Creating a preferred drug list, which is a list of prescription drugs a health plan will

cover for its beneficiaries;

• Negotiating prices and rebates with drug manufacturers;

• Contracting with pharmacies and collective groups who negotiate on behalf of

pharmacies to create pharmacy networks; and

• Drug utilization reviews, which analyze the prescribing, dispensing, and use of

medications.

Certain PBM practices create risks for private insurers and federal and state health

programs

PBMs have merged with other entities to remain competitive and to increase their revenue streams.

Today, the largest PBMs are vertically integrated with the largest health insurance companies and retail

and mail order pharmacies.

2

Some of these large PBMs are contracted to provide pharmacy benefits for

many of Oregon’s coordinated care organizations in Medicaid.

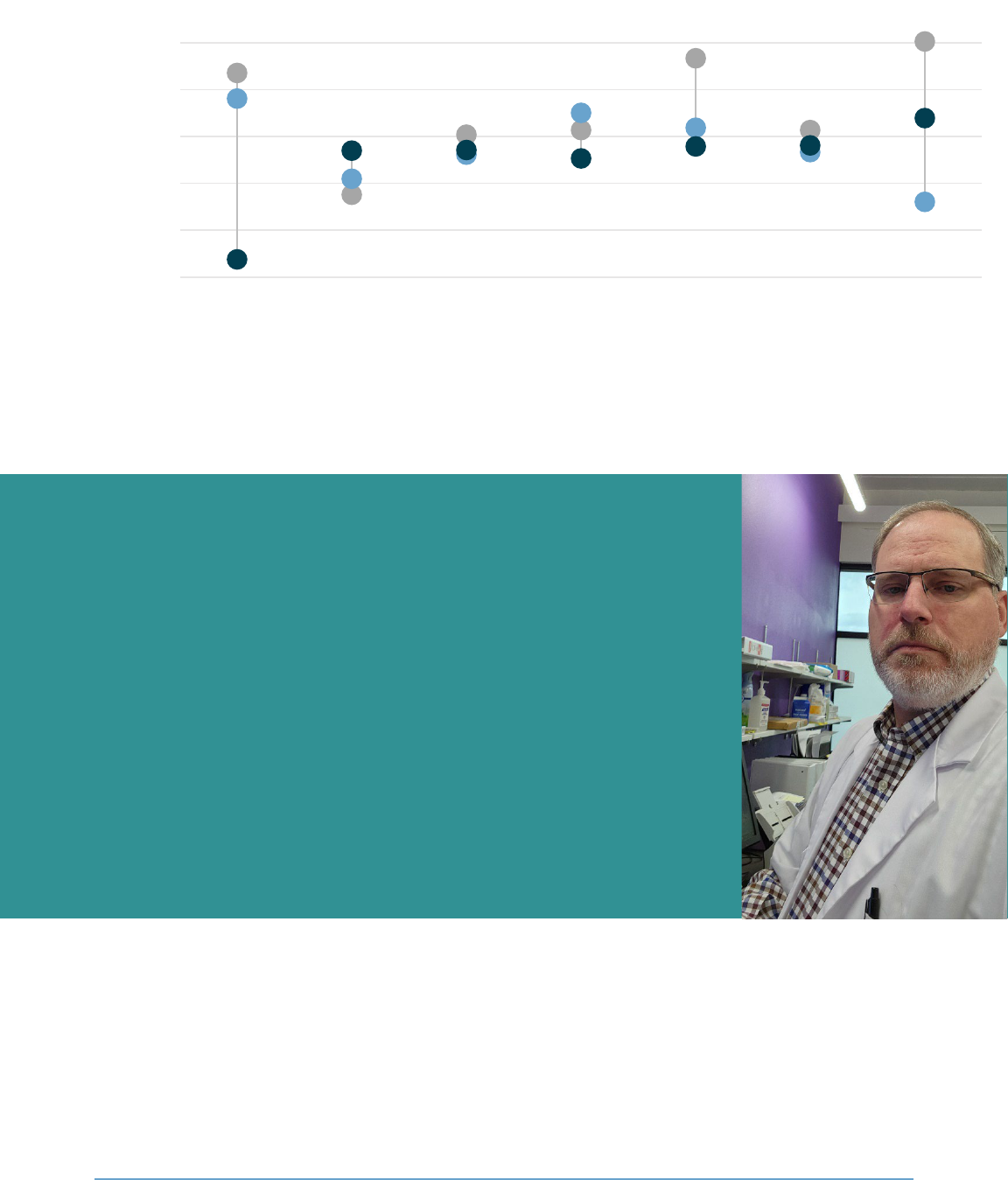

Figure 1: Three companies make up 80% of the 2020 market share of claims for PBMs

Source: Health Industries Research Companies

PBMs have considerable influence on which drugs are covered by insurers and can require consumers

to get certain prescriptions filled at a specialty or mail order pharmacy, which the PBM may own. CVS

Health, a vertically integrated system, noted in recent financial statements the rebates they receive

from drug manufacturers often depend on whether the PBM places their drugs on a health plan’s

preferred drug list. Vertical integration in the pharmaceutical system poses risks of decreased

consumer access to medications and affordability to everyone, not just those receiving Medicaid

benefits.

2

Vertical integration in health care refers to the mergers and acquisitions of companies that offer diversified services and/or

products across a continuum of health care services.

CVS Caremark

34%

Express Scripts

25%

Humana 8%

Prime Therapeutics 6%

MedImpact 4%

All others 3%

OptumRx

21%

The United States is the only developed country that uses PBMs for its public health programs.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 3

Figure 2: A hypothetical example of a patient who receives care from vertically integrated entities

Source: Auditor created based on CVS and subsidiary information

PBMs are involved in many aspects of the prescription drug supply chain, and because of that, there is

a risk that reported cost savings may not be accurately reflected. For example, a manufacturer lists the

price of a drug at $10. The PBM tells the insurer they can negotiate a discount on the drug, but then

the list price goes up to $25. The PBM negotiates with the manufacturer to get the price back down to

$10 and can then report to the insurer that they saved $15 on that prescription, when the cost did not

actually change from $10. Depending on the contract a PBM has with an insurer, they may get to keep

a portion of the rebates, or discounts, received from drug manufacturers.

The deals PBMs negotiate with insurers, manufacturers, pharmacies, and other entities are often

considered trade secret information and do not have to be shared. This opaque system makes it

impossible to understand the actual costs of prescription drugs and has garnered attention at multiple

levels of government.

In 2022, the Federal Trade Commission announced it would launch an inquiry into PBMs, requiring them

to provide information and records regarding business practices owing to the lack of transparency and

size of the largest PBMs. The inquiry will target high-risk PBM practices, such as:

• Fees and clawbacks charged to unaffiliated pharmacies;

3

3

Practice of charging co-payments to consumers for certain prescription drugs that exceed the cost of medicines, with the

difference required to be returned to the PBM by the pharmacy.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 4

• Methods to steer patients toward PBM-owned pharmacies;

• Potentially unfair audits of independent pharmacies;

• Complicated and opaque methods used to determine pharmacy reimbursements;

• The prevalence of prior authorizations and other administrative restrictions;

• The use of specialty drug lists and related specialty drug policies; and

• The impact of rebates and fees provided by drug manufacturers on preferred drug

list design and the costs of prescription drugs to payers and patients.

Spread pricing is another high-risk area. Spread pricing has been cited as costing governments,

pharmacies, and patients more money for the delivery of prescription drugs. Spread pricing occurs

when a PBM keeps the difference between what is charged to the health plan and what is reimbursed

to a pharmacy. For example, an insurer agrees to pay a PBM $100 for a prescription, but the PBM’s

contract with the pharmacy states it will reimburse the pharmacy $75. If the PBM keeps the $25

difference, this is considered spread pricing. Health plans often do not know the amounts reimbursed

to pharmacies, as PBMs would consider that information proprietary. At least 11 states have banned

spread pricing in their Medicaid programs. In Oregon, CCOs and their PBMs are permitted to split the

spread, depending on their contracts.

Figure 3: Spread pricing happens when PBMs keep the difference between what is paid to health plans and

pharmacies

Some contracts with PBMs state the difference will be split between them. In the example above, both

the insurer and PBM would each keep $12.50 if the difference were split evenly. Oregon’s Medicaid

program allows PBMs to operate under either a pass-through contract or a model where the PBM and

CCO each receive a portion of the spread, known as a pay-for-performance contract. While spread

“Although many people have never heard of pharmacy benefit managers, these

powerful middlemen have enormous influence over the U.S. prescription drug

system.”

Lina M. Khan, Federal Trade Commission Chair

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 5

pricing poses risks, there are other transactions outside of the claims payment process possibly

affecting costs at the pharmacy level and PBM revenues. There are additional fees PBMs can receive

from insurers, pharmacies, and drug manufacturers that are considered proprietary information, which

makes it even more challenging for Medicaid programs to truly understand the actual cost of pharmacy

benefits.

Medicaid, the largest and most complex government program in

Oregon, uses PBMs for most pharmacy benefits

Across the nation, Medicaid programs and public employee health plans are evaluating their

relationships with PBMs due to concerns about the complexity of the process, transparency, and rising

costs. Medicaid is a government program providing health care coverage to low‐income adults,

children, pregnant people, the elderly, and people with disabilities. It is financed through federal and

state funding and is administered by each state.

Figure 4: Oregon spends more on Medicaid than any other program

Source: Auditor-created based on the State of Oregon 2020 Financial Condition Report

In 2020, Oregon spent more on the Medicaid program than it did on any other area, including education,

transportation, and public safety combined.

4

As of January 2023, about 1.4 million people in Oregon

receive Medicaid benefits. In 27 counties in Oregon, more than one-third of the population receives

Medicaid benefits.

The federal government estimates national Medicaid expenditures will increase to over $1 trillion by

2028; state officials estimate the cost of health care in Oregon will grow faster than the state’s

4

State of Oregon 2020 Financial Condition Report

Medicaid

32%

Education

19%

Other

15%

Unemployment

13%

Human services

10%

Transportation

5%

Public safety

5%

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 6

economy. Due to the size and dollar amounts flowing into this program, it is important the state take

steps to ensure the program is run efficiently and effectively to better serve people in Oregon.

Figure 5: In most Oregon counties, one-in-three people received Medicaid benefits in 2022

Source: OHSU’s Office of Rural Health

The Oregon Health Authority administers Medicaid in Oregon

Oregon’s Medicaid program, also known as the Oregon Health Plan, is administered by the Oregon

Health Authority (OHA).

5

OHA’s 2021-23 biennial budget is over $32 billion with 5,100 full-time

employees across seven divisions. OHA works closely with other state and local agencies, as well as

Tribal governments, to provide services and health care to people in Oregon.

Medicaid is the largest program under OHA and accounts for 68% of the agency’s budget. OHA’s Health

Systems Division oversees the Medicaid program and sets guidelines regarding eligibility and services in

accordance with federal requirements.

The Oregon Department of Human Services also oversees some Medicaid-funded programs that

provide care to clients in their own homes or communities. These programs serve eligible, low-income

individuals. Although the department operates some pieces of Medicaid, ultimate state responsibility

for the program falls to OHA.

Six PBMs provide pharmacy benefits for all 16 of Oregon’s Coordinated Care

Organizations

Oregon uses both fee-for-service (FFS) and coordinated care models to deliver services. The FFS

model is the more straightforward of the two: a Medicaid client visits a health care provider, the

5

Oregon Health Plan coverage also includes the Children’s Health Insurance Program, Reproductive Health Equity Act, Cover All

Kids, and the Cover All People programs.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 7

provider bills OHA directly for approved services, and OHA pays the provider. About 10% of Medicaid

clients in Oregon are FFS.

6

Figure 6: Coordinated Care is a more indirect payment system than FFS

The coordinated care model involves coordinated care organizations, or CCOs. A CCO is a network of all

types of health care providers (physical, behavioral, and dental care providers) who work together in

their local communities to serve people who receive coverage under Medicaid. CCOs focus on

prevention and helping people manage chronic conditions. Oregon currently has 16 CCOs providing

coverage across the state.

Figure 7 shows a simplified version of the complex relationships PBMs, CCOs, OHA, and other entities

have in the Medicaid prescription drug system. A more complete chart that accurately depicts these

complex relationships can be found in Appendix B.

6

Mental health drugs are carved out from coordinated care benefits, even if the person is enrolled in a CCO. This 10% only

includes people not enrolled in a CCO.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 8

Figure 7: Medicaid PBMs operate in a complex environment involving many different entities

Source: Auditor-created, simplified model of Oregon’s PBM structure based on information from OHA and the Congressional

Budget Office. See also Appendix B

for a comprehensive flowchart of Oregon’s pharmaceutical supply chain.

OHA pays CCOs predetermined rates, known as capitated payments, every month for each Medicaid

client for covered services. CCOs receive these payments no matter how many or how few services a

Medicaid client uses in a month. In 2023, the average capitated payment is $507.90, but rates vary

among CCOs, age ranges, and other factors.

CCOs pay providers and subcontractors, like PBMs, for services rendered and send encounter data to

OHA. This data shows the services provided to clients and helps set future rates for capitated

payments. Medicaid patients do not have out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs, even if they have

additional health insurance, which is always billed first. Figure 8 lists the 16 CCOs, their PBM

subcontractors, and the number of people enrolled as of January 2023.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 9

Figure 8: CCOs currently contract with six entities who provide pharmacy benefits

CCO PBM(s)

7

January 2023 enrollment

Advanced Health MedImpact 27,204

AllCare MedImpact 61,884

Cascade Health Alliance MedImpact 25,520

Columbia Pacific OptumRx 35,344

Eastern Oregon Navitus (Oregon Prescription Drug

Program)

71,475

Health Share Multiple

8

427,339

InterCommunity Health Network OptumRx 80,126

Jackson Care Connect OptumRx 62,681

PacificSource- Central CVS Caremark 73,117

PacificSource- Columbia Gorge CVS Caremark 16,841

PacificSource- Lane CVS Caremark 89,098

PacificSource- Marion/Polk CVS Caremark 140,073

Trillium Community Health-

Southwest

Envolve Pharmacy Solutions 35,874

Trillium Community Health- Tri-

County

Envolve Pharmacy Solutions 38,381

Umpqua Health Alliance MedImpact 36,797

Yamhill Community Care Providence 34,778

FFS N/A 129,230

Total 1,385,762

Source: OHA PBM and Medicaid enrollment information

Pharmacy benefits continue to be a large spending category for CCOs

OHA estimates about 14% of each monthly capitated payment sent to CCOs is for prescription drugs. It

is important to note this estimate does not include drugs given in a hospital setting or drugs

administered by physicians. Mental health drugs are also excluded, as they are paid under the FFS

model, even if the person is enrolled in a CCO.

9

In 2021, about 11.8 million Medicaid prescriptions were

dispensed at pharmacies, and CCOs reported spending $767 million on prescription drug benefits, while

FFS drug expenditures were $208 million.

10

Generic drugs are the most prescribed medications, but specialty drugs make up a disproportionate

share of total expenditures. There is no single agreed-upon definition of a specialty drug between PBMs

and insurers. Definitions vary, but can include high-cost medications, drugs that require special

handling, availability limited to certain pharmacies, and drugs that treat rare diseases. Some generic

drugs can cost $2 or less, while some specialty drugs can cost over $100,000 per prescription. Generics

7

Some CCOs have changed PBMs in the past five years. Figure 7 reflects the CCO-PBM relationships as of January 2023.

8

Health Share has multiple subcontractors, each with their own pharmacy benefit relationship. These include OHSU, Providence,

Kaiser, CareOregon, OptumRx, and Legacy/Pacific Source.

9

Per OAR 410-141-3855, mental health drugs in Standard Therapeutic Classes 7 and 11 are carved out from coordinated care

benefits. Providers bill OHA directly for these medications.

10

The total amount paid does not reflect any rebates received that would reduce the total amount spent. FFS and CCO claims

are both subject to federally mandated rebates.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 10

are typically lower priced than brand name drugs, but the cost of generics has also been rising. Figure 9

demonstrates the disparate share specialty drugs have on total drug expenditures at one CCO.

Figure 9: Two thirds of Medicaid prescription drug spending is for specialty and brand name drugs, despite

comprising only 5% of claims

Source: OHA and PBM data

The amount of prescription drugs claims is increasing because the prevalence of chronic conditions has

increased with the aging of the U.S. population and because new therapies and generic drugs have

become more available. In the past several decades, the country has seen large growth in medications

treating common conditions, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, anxiety, and depression.

However, the number of generic drugs may not increase as much as brand and specialty drugs in the

future due to the likelihood of newer brand and biologic drugs and the current extensive use of

generics. Biologic drugs are complex and harder to manufacture than traditional prescription drugs.

Figure 10 details some of the most expensive drugs, in total, CCOs paid for in 2021.

0.4%

5%

90%

33%

33%

20%

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Specialty drugs

Brand drugs

Generic drugs

% Claims % Spending

Specialty drugs make up less than 1% of prescriptions but are one-third of total prescription drug spending.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 11

Figure 10: CCOs spent more on Humira than any other drug at pharmacies in 2021

Brand name(s) Conditions treated

11

Claims Amount

Humira Crohn’s disease, ulcerative

colitis, plaque psoriasis

7,991 $53 million

Biktarvy HIV 8,178 $29 million

Mavyret Hepatitis C 2,072 $27 million

Lantus, Basaglar

Kwickpen, Toujeo

Diabetes 71,038 $26 million

Trikafta Cystic fibrosis 912 $22 million

Stelara Crohn’s disease, ulcerative

colitis, plaque psoriasis

947 $20 million

Trulicity Type 2 diabetes 21,249 $18 million

Enbrel Plaque psoriasis, rheumatoid,

and psoriatic arthritis

2,626 $15 million

Eliquis Deep vein thrombosis 27,757 $14 million

Humalog Type 2 diabetes 42,706 $13 million

Source: OHA, the Food and Drug Administration, and Drugs.com

The average cost per prescription for more expensive drugs in Figure 10 ranges from $300 to $24,000.

Conversely, the most dispensed drugs — like albuterol sulfate, omeprazole, and ibuprofen — have an

average cost per prescription of $3 to $35.

Understanding the true cost of prescription drugs is difficult. Costs are often obscured by

nondisclosure agreements throughout the distribution chain. For example, wholesale acquisition cost is

the drug manufacturer’s list price to wholesalers; however, this is typically not the actual price paid.

The average wholesale price is the published list price for drugs sold by wholesalers to retail pharmacies

and is used as a starting point for negotiations.

Drug cost inputs are not always available and determining actual prices paid is difficult without access

to confidential information. Many negotiated drug prices are proprietary and known only to the parties

involved in the transaction. Drug manufacturers do not provide public information on how they set the

list price and have often not been required to explain changes in a drug’s list price.

12

PBMs add an

additional layer of complexity, as the prices paid to drug manufacturers and reimbursements to

pharmacies are also considered proprietary information. States are required to invoice manufacturers

for rebates on covered drugs for Medicaid. OHA has full visibility of the net cost of drugs under FFS, but

not in coordinated care. While increased transparency in prescription drug prices may not directly

lower costs, it will help policymakers better understand which prescription drugs and which portions of

the supply chain are cost drivers.

Oregon has placed an emphasis on drug manufacturers, but PBMs have received less

scrutiny

In 2018, the Oregon Legislature enacted the Prescription Drug Price Transparency Act. Housed in the

Department of Consumer and Business Services (DCBS), the act established the Task Force on Fair

11

Other conditions may be treated with these medications.

12

House Bill 2658 requires drug manufacturers to report to DCBS specific information on price increases for certain medications.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 12

Pricing of Prescription Drugs. The task force was directed to create a strategy for understanding the

pieces of the pharmaceutical supply chain and make recommendations to the Legislature to bring more

transparency. The task force made 15 recommendations, one of which focused on PBMs.

13

As of the

time of this report, only one of the recommendations has been fully implemented, one is partial, and 13

have not been implemented, which includes the PBM-focused recommendation.

After the recommendations were made, the task force was disbanded, and the Prescription Drug Price

Transparency Program took over at DCBS. The program compiles specific cost and price information

from manufacturers and health insurers and issues yearly reports on their findings.

14

However, most

efforts are focused on drug manufacturers.

Oregon is one of a handful of states in the country with a Prescription Drug Affordability Board. The

board was established in 2021 to protect stakeholders within Oregon’s health care system from the

high costs of prescription drugs. The board studies the prescription drug distribution and payment

system in Oregon and looks at policies adopted in other states and countries with the goal of lowering

the list price of prescription drugs for people in Oregon. The board releases two yearly reports detailing

its findings and recommendations.

15

One report is targeted to OHA and the Legislature, and the other is

an informational report on the generic drug marketplace.

DCBS is the regulator of the insurance industry in Oregon and is

charged with registering PBMs. Starting in 2013, PBMs must be

registered to conduct business in the state and renew annually.

While DCBS can also investigate complaints lodged against

PBMs for several reasons, staff noted complaints in the last few

years have been minimal and there have not been any

significant investigations aimed at PBM misconduct to date.

DCBS reported receiving 123 PBM complaints from 2015 – 2022

and three so far in 2023. Most of these complaints were closed

with no action determined to be needed, according to DCBS’s interpretation of Oregon or federal

statutes. Pharmacists we spoke to say the complaint process is onerous and ineffective; they have

stopped lodging complaints unless they are particularly egregious.

Current statutes define PBMs as organizations contracting with pharmacies on behalf of an insurer

offering a health benefit plan, a third-party administrator, or the Oregon Prescription Drug Program.

16

DCBS does not consider Medicaid PBMs to fall under the current definition; therefore, they are not

subject to most statutory requirements and go unregulated by DCBS. The Legislature should add

Medicaid PBMs to the definition in ORS 735.530.

13

Task Force on Fair Pricing of Prescription Drugs report

14

DCBS Prescription Drug Price Transparency reports

15

DCBS Prescription Drug Affordability Board Reports

16

ORS 735.530

Examples of PBM complaints DCBS

can investigate

• Maximum allowable cost violations

• Pharmacy auditing violations

• Fraud

• Patient steering

• Anti-gag clause violations

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 13

Prescription drugs are important for patients’ health and wellbeing, warranting

government regulation

The Federal Trade Commission enforces non-criminal antitrust laws in the U.S. to prevent and eliminate

anticompetitive business practices, including monopolies.

17

However, there are certain industries where

monopolies are allowed and are regulated for the public good, like utilities. Utility companies hold

natural monopolies over certain service areas. These natural monopolies provide greater efficiency and

economies of scale. To compensate for this, the government heavily regulates them to protect

consumers. Government agencies currently regulate utility companies for prices charged to customers,

budgetary processes, construction of new facilities, services offered, and energy efficiency programs.

These monopolies provide critical services that heat homes, water crops, and make economy

sustaining industry possible.

Utilities are essential to people’s wellbeing and a similar argument can be made for prescription drugs.

Patients need critical or lifesaving prescription drugs to treat high blood pressure, heart disease,

asthma, diabetes, mental illness, among many other conditions. Without these prescriptions, patients

would have a lower quality of life and possibly live shorter lives. Because a handful of PBMs control

most of the market and vertical integration has become more prevalent, there is a possibility the

industry is at risk of anti-competitive practices. Given the necessity for medications and their overall

importance to the public good, there is a need for reasonable government regulation.

“This unfair squeeze by PBMs on independent pharmacies in

Oregon and throughout the country poses a direct threat to

these community mainstays’ ability to stay open for their

patients who count on them for quality local service.”

-

Ron Wyden, United States Senator (Oregon)

Source: Image courtesy of www.wyden.senate.gov

As part of our strategic effort to provide real-time auditing services, we provided timely information to

Oregon’s Legislature in September 2022 and February 2023, as seen in Appendix C. Real-time auditing

focuses on evaluating front-end strategic planning, service delivery processes, controls, and

performance measurement frameworks before or at the onset of significant program or public policy

implementations by state agencies.

17

Investopedia What Is a Monopoly? Types, Regulations, and Impact on Markets A monopoly is a market structure where a single

seller or producer assumes a dominant position in an industry or a sector. Monopolies are discouraged in free-market economies

as they stifle competition and limit substitutes for consumers.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 14

Audit Results

Prescription drug prices have become a major concern across the U.S. In 2021, Oregon spent

approximately $767 million a year on retail prescriptions for Oregon Health Plan CCOs. While there have

been state and federal efforts to control drug prices, these efforts have primarily focused on drug

manufacturers while PBM risks, including a lack of transparency, have largely been overlooked. Other

states have passed meaningful legislation requiring more accountability from PBMs that have brought

more transparency to the prescription drug supply chain. To date, there has been some PBM reform

legislation proposed in Oregon, but more should be done.

This audit identified areas of concern including the current structure of Medicaid PBMs in Oregon and

OHA’s monitoring controls over CCOs and their contracted PBMs. The current structure lacks

transparency and is overly complex — as a result, it is difficult to determine the value provided to the

program and to people in Oregon. Transparency and accountability are obscured by nondisclosure

agreements and proprietary information. The current system does not support local community

pharmacies, which are a critical component of health care for all people in Oregon, not just those

receiving Medicaid benefits.

Oregon’s Legislature should follow leading practices in other states and create a universal preferred

drug list for Medicaid, require PBMs to act as fiduciaries, prioritize fair pharmacy reimbursements,

require PBMs to disclose cost information, and adopt a new PBM structure in Medicaid.

We also found PBM provisions in the CCO contracts have been strengthened, but OHA’s monitoring

controls are not sufficient to determine compliance and do not cover high-risk areas. Oregon has an

opportunity to regulate PBMs to increase the value they provide to the Medicaid program by adopting

leading practices to improve pharmacy access, improve transparency in the prescription drug process,

and potentially save taxpayer dollars.

Oregon’s Medicaid program cannot assess the public benefit of

hundreds of millions paid to pharmacy benefit managers

Regulation of PBMs in Oregon is limited and fragmented. DCBS monitors PBMs operating in the

commercial insurance space but not in Medicaid. Medicaid PBMs are subcontractors of CCOs, and OHA

does not have direct supervision over them. Statutory changes are needed in order to provide the

state with direct oversight of all PBMs.

Other states have passed laws increasing protections for patients and community pharmacies related

to PBMs. Some of these protections include uniform preferred drug lists, fair pharmacy

reimbursements, increased transparency, and changes to state Medicaid PBM models. We recommend

Oregon’s Legislature consider addressing all of these factors, to the benefit of the many Oregonians

who rely on prescription medications.

Oregon has been slow to address PBM reforms, falling behind many other states that

have passed significant PBM legislation

Policymakers across the country are taking different approaches in tackling rising prescription drug

costs. Other states have focused efforts on PBM reforms, while Oregon continues to focus primarily on

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 15

drug manufacturers. Oregon took some early steps to reduce prescription drug costs, but progress

since then has been minimal compared to other states

One early step Oregon took was the creation of the Oregon Prescription Drug Program (OPDP), which

is administered by OHA. OPDP was established in 2003. Currently, the program purchases prescription

drugs, reimburses pharmacy claims, creates a standard preferred drug list, and operates a prescription

discount card program.

18

One of OPDP’s goals is to ensure the most effective drugs are available at the

best prices to the insurers who use the program. OPDP eventually joined Washington State and formed

a consortium in 2006, expanding the purchasing power of the program. In 2022, the State of Nevada

joined the consortium and expansion to other states continues to be explored.

Currently, the program administers pharmacy benefits for 13 different institutions and programs across

three states, including the State Accident Insurance Fund, Oregon Health and Sciences University, and

the State Hospital and covers over 225,000 lives just within Oregon. CCOs can also choose OPDP to

administer pharmacy benefits; however, only one has chosen to do so.

In 2019, legislation was passed stating PBMs could not prohibit a network pharmacy from offering

delivery of prescription drugs to consumers. In the same bill, the Legislature prohibited PBMs from

restricting or penalizing a network pharmacy from informing a customer of the difference between

their out-of-pocket cost and the pharmacy's retail price for the drug. This was implemented in Oregon

after several other states had passed similar legislation. Many other states are currently making inroads

to dealing with spread pricing and PBM transparency issues as well. Although the Legislature has

demonstrated bipartisan interest in reforming PBMs, other issues have taken priority, including the

pandemic and several natural disasters.

The pharmaceutical industry also has strong lobbying power in the Oregon Legislature and has donated

more than $600,000 to various campaigns and funds over the past five years. The pharmaceutical

supply chain is very complex and can be difficult to understand. Since pricing and cost information can

be considered proprietary, policymakers do not have enough information available to enact meaningful

change for some issues.

There are three main areas other states have focused their PBM legislation on: patient protections,

pharmacy protections, and transparency. With the national spotlight currently focused on both drug

manufacturers and PBMs, Oregon’s Legislature made some progress during the 2023 session. Bills were

passed requiring PBMs to report some information to DCBS, pharmacy retroactive fees and payment

reductions were restricted, and recurring surveys of pharmacy dispensing costs were implemented.

While these are improvements, the Legislature should do more to protect patients and community

pharmacies.

18

ArrayRx is Oregon’s prescription discount card program, which has no income restrictions or membership fees, and is available

to anyone living in Oregon.

Oregon’s PBM legislation

In the last 10 years, 28 PBM reform bills have been introduced, but only seven have passed.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 16

Oregon’s PBM structure and current statute limit patient protections for prescriptions

A preferred drug list is a list of prescription drugs covered under a health plan. Health plans use

preferred drug lists to negotiate drug rebates and encourage providers to prescribe those medications

.

Uniform preferred drug lists support administrative simplicity for providers and consistent drug

coverage for patients.

Currently, Oregon has 16 different CCOs with multiple preferred drug lists. Having multiple preferred

drug lists in Medicaid creates challenges for patients, providers, and OHA. If people move to an area

with a different CCO, the prescription drug they previously took may or may not be on the new CCO’s

preferred drug list. If a person is prescribed a medication not on the list, extra steps need to be taken

before the individual can obtain their prescription.

For example, a person who lives in Coos Bay takes a blood pressure medication that works well for

them and was prescribed by their doctor. The person moved to Clackamas and now has a new CCO,

PBM, and preferred drug list. The original blood pressure medication might not be covered on the new

list. If this happens, the person might have to try new medications first, that may not work as well, or

the provider and patient will have to start the prior authorization process, which can be burdensome to

both patients and providers.

1920

PBMs will often move drugs on and off their preferred drug list depending on research and market

conditions. Frequent changes to covered drugs are burdensome, especially when changes are not

uniform across the state. In 2018, the Oregon Health Policy Board recommended alignment of the

preferred drug lists for FFS and CCOs to the Legislature but it was never implemented. Figure 11 shows

many other states have adopted this leading practice in their Medicaid programs. To bring consistency

to patients, Oregon’s Legislature should mandate a uniform preferred drug list for Medicaid. A standard

prior authorization process would be easier to implement under a uniform preferred drug list.

19

Prior authorization requires prescribers to receive pre-approval for prescribing a particular drug for that medication to qualify

for coverage under the terms of the pharmacy benefit plan. Prior authorization processes can differ among CCOs.

20

OAR 410-141-3850 requires CCOs to provide continued access to services when a Medicaid recipient moves from another CCO.

This rule does not apply to a Medicaid recipient who has a gap in coverage following disenrollment due to failure to respond to

mail from OHA that was sent to the recipient’s prior address. Under the existing model, there remains different access to

prescription drugs for Medicaid recipients depending based on where they live.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 17

Figure 11: Many states have adopted policies for uniform preferred drug lists for all or some drug classes in

Medicaid coordinated care

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

Another patient protection other states have implemented is requiring PBMs to act as a fiduciary.

Fiduciaries are organizations acting on behalf of another person or entity, with a duty to preserve good

faith and trust, putting their client’s interests ahead of their own. Fiduciaries are legally and ethically

bound to act in the best interest of the people they serve.

Several states require all PBMs operating within the state, including commercial and Medicaid PBMs, to

sign contracts that include fiduciary clauses. According to these clauses, not only will the PBM act in

the best interest of the insurer they subcontract with, but they will also act in the best interest of the

beneficiaries of the insurer. This helps ensure the PBM will act in their self-interest only if the act does

not harm or reduce value to the program or the person. State Insurance Commissions are typically the

oversight body in states that have adopted this leading practice.

Pay-for-performance contracts create confusion and obstacles to transparency

CCOs may choose between contracting with OPDP or selecting a different PBM to provide services, as

they almost all have. CCOs might choose to use a different PBM, rather than OPDP, because they offer

other insurance plans outside of Medicaid that they already have a contracted PBM for. If CCOs choose

to use a different PBM, they can decide between two contract types: pass-through or pay-for-

performance. A pass-through contract states the PBM will pass through any negotiated manufacturer

States with fiduciary clauses

California, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, New York,

Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Vermont.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 18

savings, like discounts or rebates, to the CCO. Under this model, administrative fees for each claim paid

to the PBM by the CCO are typically higher. When CCOs choose a pay-for-performance contract, the

PBM passes through rebates and usually sets a much lower administrative fee; however, the PBM will

share a quarterly payout, based on performance, with the CCO. This payout is based on two key

factors: negotiating drug discounts from manufacturers worth more than the amount stipulated in the

contract and paying a smaller per-claim dispensing fee to pharmacies than the fee stipulated in the

contract.

Determining rebate pass-through is more complicated in a pay-for-performance model. Auditors

examined aggregate rebate data for both contract models. The pass-through contracts were clearer to

understand, while pay-for-performance aggregate rebate and discount totals were difficult to

determine. By requiring all PBM contracts to be pass-through, OHA could increase transparency for

dispensing fees and drug rebates and improve its own ability to review and monitor these contracts.

Low or unfair reimbursement rates have been attributed to a decline in local, sole

proprietor pharmacies, a critical component of the state’s health care system

Pharmacies are a critical element of health care and are important in promoting health outcomes, but

the number of independent, smaller pharmacies in many parts of Oregon has been dwindling. Closures

have been driven in part by low or unfair reimbursement rates, making it difficult for these pharmacies

to stay open and retain staff. Some PBMs pay pharmacies about a dollar more for dispensing

prescriptions in underserved areas, but this increase likely does not cover operating costs for the

pharmacy. Dispensing fees paid to pharmacies under FFS are much higher. Taking legislative action to

protect reimbursement rates is a critical step in keeping pharmacies open to the benefit of all

Oregonians, not just those on Medicaid.

“When people truly need help, they come to the

most accessible health care professional in their

community... we serve over 3,000 square miles as

the only local providers. People literally drive hours

to get our help; whether it’s antibiotics, pain

medications following surgery, flu or covid

vaccinations, diabetic medications, or professional

advice on complex medication situations. The

services we provide are real and valuable!”

-

John Murray, Rph, independent pharmacy

owner in Heppner, written legislative

testimony in support of House Bill 3013 in

2023

Pharmacists are ideally positioned in their respective communities to address gaps in care by

collaborating with other health care providers, which can help eliminate health disparities. A 2016 study

found as the availability of pharmacies in a given area increased, hospital readmissions for people in

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 19

Oregon 65 or older decreased.

21

In the U.S., it is estimated medication nonadherence is associated with

125,000 deaths, 33%-69% of medication-related hospitalizations, and $100 to $300 billion in health

care services annually.

22

Pharmacists can help improve medication adherence and management of

chronic diseases and potentially reduce costly hospital readmissions.

The number of local and independent pharmacies has been falling across the nation. Pharmacy closures

disproportionately affect Black and Latino communities. Closures have also negatively impacted

Oregon’s rural communities, which have higher barriers to accessing medications.

23

Sixteen counties in

Oregon are below the national average for community pharmacies per 10,000 people, as shown in

Figure 12.

Figure 12: Sixteen Oregon counties are below the national average for community pharmacies

Source: Auditor analysis of Portland State University Population Center data, pharmacy data from the Oregon Board of

Pharmacy, and the National Institute of Health

Although the map shows that many rural counties are in line with national averages, the ratio mapped

does not consider the geographic size of a county. Some rural counties are over twenty times larger

geographically than their urban counterparts while most have far fewer than a twentieth of the

population. This means rural counties with only one or two pharmacies serving a large geographic area

can have a pharmacy to resident ratio in line with national averages. But the nearest pharmacy to many

residents still may be hours away. Fewer pharmacies in any given area translate to longer drive times

and increased wait times at existing pharmacies. Mail order pharmacies can be helpful to those in

21

Journal article- Pharmacy density in rural and urban communities in the state of Oregon and the association with hospital

readmission rates

22

Medication adherence generally refers to patients taking their medications as prescribed and as long as prescribed.

23

Journal article- Independently Owned Pharmacy Closures in Rural America

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 20

remote areas, but do not provide the same in-person care as community pharmacies. Sometimes there

are issues with timely deliveries, which can be critical for people on certain medications.

Low or unfair reimbursement rates have been cited as a key factor for pharmacy closures. A national

study in 2020 found the average cost for pharmacies to dispense each prescription was over $12.

24

Most of this cost is to support employment of pharmacists and technicians. Pharmacists report

inconsistent reimbursements make it challenging to adequately staff and resource retail pharmacies.

Pharmacists we interviewed noted there are some prescriptions they lose money on, some they make

a little profit on, and a small number they make a significant amount of profit on. PBMs can set

pharmacy reimbursement rates, which can vary significantly between drugs and pharmacy types.

Figure 13: CCOs reported spending $767 million on prescription drugs in 2021

Source: OHA publicly reported financial data

Other states have provisions in statute to address this issue. For instance, Kentucky prohibits PBMs

from reducing the amount reimbursed on a claim to effective rates; other states require the use of

National Average Drug Acquisition Costs as a basis for reimbursement when available. Arizona requires

PBMs to disclose the methodology for maximum allowable cost lists to provider pharmacies. Oregon

has no such provisions in statute. In some states these middlemen have been removed entirely from

their Medicaid coordinated care programs.

We analyzed 316,755 Medicaid claims to assess how pharmacy reimbursements may vary. Of the claims

we tested, 69% were far below the $12 average cited in the 2020 study. In our testing, more frequently

dispensed drugs — like metformin and omeprazole — tended to have much lower estimated pharmacy

profits than less frequently dispensed medications. For the 13 drugs tested, the average estimated

profit was $7.16 per claim, which likely is not enough to cover labor and other operating costs.

24

See the 2020 Cost of Dispensing Study commissioned by national pharmacy associations.

$226

$506

$523

$658

$698

$989

$251

$642

$649

$767

$949

$1,191

Emergency room

Mental health

Hospital- outpatient

Prescription drugs

Hospital- inpatient

Physician/professional services

$0 $1,200

●2019 ●2021

in millions

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 21

Overall, our analysis shows pharmacy reimbursements vary significantly between drugs, pharmacy

type, and PBM, as shown in Figures 14, 15, and 16. Pharmacies often lose money when filling certain

prescriptions and pharmacists have reported patients are sometimes turned away if a prescription will

cost the pharmacy too much money. In 2021, pharmacies dispensed over 12,000 acetaminophen

(Tylenol) prescriptions and, on average, made only $0.35 on each prescription. Pharmacies also

dispensed almost 71,000 albuterol sulfate prescriptions with a total estimated loss of over $1.3 million

or about $19 lost per prescription filled. Albuterol sulfate is an important lifesaving drug used to treat

breathing conditions due to asthma and allergies and is one of the most commonly dispensed

medications in Medicaid.

Figure 14: Pharmacy reimbursements vary widely between selected prescription drugs in 2021

Drug Number of

claims tested

Dollar amount

tested

Estimated total

pharmacy

profit/loss

Estimated average pharmacy

profit/loss per claim

Acetaminophen

(Tylenol)

12,178 $28,349 $4,269 $0.35

Albuterol Sulfate 70,955 $2,766,642 -$1,315,643 -$18.54

Amoxicillin 13,608 $51,462 $35,067 $2.58

Basaglar 45,767 $16,790,230 $219,619 $4.80

Biktarvy 6,195 $20,369,308 $192,792 $31.12

Budesonide and

Formoterol

Fumarate Dihydrate

14,924 $4,079,910 $865,952 $58.02

Buprenorphine and

Naloxone

26,101 $3,766,875 $1,238,829 $47.46

Eliquis 17,743 $8,457,352 $48,779 $2.75

Flovent 12,868 $3,357,669 $56,127 $4.36

Humira 3,947 $26,178,519 $25,836 $6.55

Metformin 26,184 $124,781 $62,680 $2.39

Omeprazole 47,812 $176,185 $117,167 $2.45

Trulicity 18,473 $15,267,881 $716,139 $38.77

Total 316,755 $101,415,163 $2,267,613

Source: Auditor analysis of OHA and PBM 2021 claims data and Oregon average acquisition cost data

Potential monopoly power may be putting patients and independent

pharmacies at risk

Pharmacies made profits on certain drugs, but those amounts vary widely and likely do not cover the

operating and overhead expenses incurred by the pharmacy. We found local, independent pharmacies

are more likely to be reimbursed less for prescriptions than national chain pharmacies. Figure 16

highlights the reimbursement disparity between pharmacy type and some name brand drugs per

prescription, like Humira and Biktarvy. For both drugs, the estimated profits for national chain

pharmacies are more than three times the amount that independent pharmacies made.

The Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America encourages states to adopt policies that promote access to

life saving medicine such as albuterol sulfate.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 22

In our testing, we estimate independent pharmacies, on average, are reimbursed less than national

chain pharmacies for most of the 13 drugs tested. For example, for each Eliquis prescription dispensed,

independent pharmacies lost on average about $3, whereas national chains made over $5. As we only

tested a small portion of pharmacy claims, we cannot conclude other drugs would show these same

disparities.

Figure 15: Medicaid PBMs consistently reimbursed pharmacies significantly below average acquisition cost

for more than 70,000 albuterol sulfate prescriptions in 2021

Source: Auditor analysis of OHA and PBM 2021 claims data and Oregon Average Acquisition Cost data

Figure 16: Estimated pharmacy profits for some brand name drugs differ significantly depending on

pharmacy type

Source: Auditor analysis of OHA and PBM 2021 claims data and Oregon Average Acquisition Cost data

-$32

-$24

-$17

-$14

-$13

-$9

($35)

($30)

($25)

($20)

($15)

($10)

($5)

$0

PBM 1 PBM 2 PBM 3 PBM 4 PBM 5 PBM 6

$58

$53

$27

$23

$7

$58

$48

$103

$45

$64

$61

$33

-$15

$48

$121

($25)

$0

$25

$50

$75

$100

$125

Budesonide Buprenorphine Humira Trulicity Biktarvy

Independent

National chain

Specialty/mail order

On average, the estimated profits for national chain and specialty/mail order pharmacies are more than

twice the amount independent pharmacies receive.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 23

Figure 17: National and specialty/mail order pharmacies were reimbursed more than independent

pharmacies for most drugs tested

Source: Auditor analysis of OHA and PBM 2021 claims data and National and Oregon Average Acquisition Cost data

Long wait times, low pharmacy density, and unfair pharmacy reimbursements pose access issues for all

people in Oregon, not just Medicaid patients. Oregon’s Legislature should enact legislation prioritizing

fair and consistent reimbursement for community pharmacies.

“A little over a month ago our pharmacy got a desperate call from a woman from Madras. It was late

on Friday and her husband had been prescribed... a critical medicine to keep him out of the hospital.

She went to the only chain pharmacy open in town and they told her it would be Monday before

they could fill it. You see, both Bi-Mart and Hometown drugs had closed. Their pharmacy business

was booming but their reimbursements were too low to stay open. The remaining chain pharmacy in

town was so overwhelmed their wait times were measured in days. She called two chain pharmacies

in Redmond and could not get anyone to answer the phone. Again, reimbursements are too low to

keep adequate staffing, even to answer the phone. Then she called us. We told her to come right

away as it was close to closing and when she arrived, we quickly filled the prescription. She had lots

of questions and health care concerns, as she had not been able to speak to a pharmacist since

Hometown drugs had closed. When she left it was 30 minutes after closing and we felt happy that

we had helped someone in need that day. I then checked my reimbursement and found that I got

paid $26 below my acquisition price for that drug. This is not the value of the service we provided

that night. Independent pharmacies, in particular, have an important value to their communities, and

they should be paid fairly for that value.”

-

Kevin Russell, RPh, MBA, BCACP, Director of pharmacy at Prescryptive Health, oral

legislative testimony in support of HB3013 2023 regular session

Other states require PBMs to disclose certain information to better assess their value and

increase transparency

A lack of transparency in PBM processes has led many states to implement laws requiring PBMs to

disclose certain pricing and cost information. Information disclosed includes aggregated data on

($3.50)

($1.50)

$0.50

$2.50

$4.50

$6.50

Eliquis Acetaminophen Omeprazole Metformin Flovent Amoxicillin Basaglar

● Independent ● National chain ● Specialty/mail order

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 24

rebates, payments, and fees collected from drug manufacturers and pharmacies. Prior to 2023, PBM

reporting requirements have been established in 16 other states.

25

Figure 18: Before 2023, other states have passed laws requiring greater reporting for PBMs

Source: National Council of State Legislatures

To better understand this complex and often opaque system, policymakers should have information

available to them to make informed decisions and help determine whether PBMs and other key players

are providing benefits and delivering good value to Oregonians. Figure 19 compares Oregon to other

states that require PBMs to report certain financial information. Oregon’s initiatives were only recently

adopted in the 2023 session, but the Legislature should require PBMs to report admin fees and spread

pricing retained, as well as collecting de-identified data.

Figure 19: Oregon lacks some of the aggregated PBM transparency initiatives adopted in other states

OR CT GA IN IA LA MI MN MT NV NH NY TX UT VT VA WI

Drug rebates from drug

manufacturers or other

sources

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

Drug rebates passed though

and/or retained

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

Admin fees from health plans ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

Admin fees from pharmacies ● ● ● ● ● ●

Admin fees from drug

manufacturers

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

All admin fees retained ● ● ● ● ● ●

Spread pricing retained ● ● ● ● ●

Data collection ● ● ● ●

Public reporting ● ● ● ● ● ●

25

In the 2023 session, the Oregon Legislature passed Senate Bill 192, which requires PBMs to submit some information annually

to DCBS.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 25

Source: States’ legislative websites

To illustrate the importance of capturing pricing information from PBMs, Figure 20 highlights how

reimbursement prices can vary dramatically. For Trulicity, a medication used for the treatment of type

2 diabetes, reimbursements resulted in estimated pharmacy losses of $58.82 per prescription to

estimated pharmacy profits of $53.29 per prescription.

Figure 20: Pharmacy reimbursement rates are inconsistent among PBMs in Medicaid

Drug NDC Month PBM Number

of units

Average Oregon

acquisition cost per unit

Estimated pharmacy

profit/loss

Prescription 1 Trulicity 2143380 Apr-21 PBM 1 2 $404.31 ($58.82)

Prescription 2 Trulicity 2143380 Apr-21 PBM 2 2 $404.31 ($16.58)

Prescription 3 Trulicity 2143380 Apr-21 PBM 3 2 $404.31 $9.57

Prescription 4 Trulicity 2143380 Apr-21 PBM 4 2 $404.31 $19.50

Prescription 5 Trulicity 2143380 Apr-21 PBM 5 2 $404.31 $53.29

Source: Auditor analysis of OHA and PBM 2021 claims data, NDC lists, and Oregon Average Acquisition Cost data

We analyzed CCO and PBM data for aggregate dispensing fees, administrative fees, drug rebates, and

other fees or payments received between 2017 and 2021. In aggregate, PBMs reported paying less in

dispensing fees to pharmacies than what CCOs reported paying to the same PBMs for dispensing fees,

for a difference of $612,000.

Drug rebate information was also analyzed but was not clear enough to make reasonable estimates and

rebate totals were less than our expectations. For example, aggregate drug rebates received in 2021

were reported to be about $7 million while CCOs reported spending over $700 million in pharmacy

benefits. Information was not confirmed with outside sources and there are likely other PBM revenue

sources we did not analyze. The difficulty with our analysis further provides evidence the system is

extremely complicated, and OHA does not have enough resources to reasonably determine whether

Medicaid PBMs are acting in the best interest of the program and patients under the current model.

States are switching PBM models to exert better control over Medicaid prescription drug

programs

Oregon’s Medicaid program currently uses a multiple PBM model. All 16 CCOs have the choice to

contract with OPDP to administer pharmacy benefits, or the CCOs can choose to contract with their

own PBM. In this model, CCOs pay their PBMs from capitation payments received from OHA. PBMs are

typically responsible for paying and processing pharmacy claims, developing or supporting the CCO’s

preferred drug list, negotiating with network pharmacies for lower price guarantees, and contracting

with drug manufacturers for drug rebates. This model has some tradeoffs.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 26

Pros: Current model Cons: Current model

•

Easier for CCOs to coordinate care

across pharmacy and medical benefits

•

Limited monitoring and knowledge of

PBM activities by OHA

• Drug rebates, which can lead to lower

costs, are not maximized

• Health equity concerns for members who

do not have consistent access

• Does not leverage purchasing power and

economies of scale

In an FFS model, prescription drug benefits would be administered by OHA. Pharmacy claims would be

processed by the contracted pharmacy benefit administrator, who currently performs those duties for

FFS claims. In this model, a uniform preferred drug list would be more efficient to implement,

prescribers would benefit from uniformity, and pharmacies would have more consistent

reimbursements

. West Virginia calculated $54.4 million in actual savings during the first year of their

transition to FFS.

26

While there is potential for cost savings, some states, like Florida,

27

have

determined a move to this model would be more costly.

Pros: FFS Cons: FFS

•

Potential decrease in capitation costs

• Potential increase in federal drug

rebates, which could lower costs

• Reimbursement consistency

• Increased transparency: State has

greater control of plan design and would

streamline monitoring efforts

• Statewide consistency in pharmacy

benefits administration

• Uniform formulary and coverage criteria

•

Leverages economies of scale

•

Requires development of IT solutions for

CCOs to access real-time pharmacy

claims and drug utilization for care

coordination

• Additional claims processing could strain

current IT infrastructure

• Potential loss of provider tax revenue

• Potential negative impacts to 340B

providers

28

A single PBM model has been used in other states to contract with one PBM for Medicaid coordinated

care or public employee health plans. For many health plans, Medicaid is not the only line of business,

and may include private insurance or Medicare. Health plans typically contract with one PBM for all lines

of business, and a move to a single PBM model may require plans to have contracts with multiple PBMs,

which could reduce some operational efficiency

. There is also a possibility some plans could withdraw

from Medicaid. In this model, Oregon could have some flexibility to maintain certain pharmacy

revenues, depending on the program structure, whereas an FFS model would not offer this kind of

flexibility.

26

See West Virginia’s 2019 Pharmacy Savings Report

27

See Florida’s 2020 PBM Pricing Practices in Statewide Medicaid Managed Care Program Report

28

Medicaid’s 340B program requires participating drug manufacturers to provide outpatient drugs to participating pharmacies

and entities at significantly reduced prices. State Medicaid programs are prohibited from billing manufacturers for rebates on

discounted medications under this program.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 27

Pros: Single PBM Cons: Single PBM

•

Potential decrease in capitation costs

• Increased transparency: Allows the state

to set contract parameters and would

streamline monitoring efforts

• Flexibility in pharmacy provider

reimbursements

• Uniform formulary and coverage criteria

• Leverages economies of scale

• Potential to preserve 340B pharmacy

revenues, depending on structure

•

Potential opposition from health plans

• Potential decreases in efficiency at the

health plan level, due to multiple lines of

business

• Potential loss of provider tax revenue

A PBM reverse auction is an online, competitive bidding process states can use to select a PBM to

manage prescription drug benefits. An auction starts with an opening bid and PBMs submit lower

counteroffers during multiple rounds of bidding. States achieve savings by forcing PBMs to offer the

same contract terms but at a lower price than their competitors. Reverse auctions have been known to

generate significant savings in various governmental procurements. New Jersey used a reverse auction

to select PBMs for public employee health plans and estimates the state will save $2.5 billion in drug

spending between 2017 and 2022.

29

While reverse auctions can lower costs for states, bid costs should

not be the only factor to consider. There is a risk PBMs might push cost savings to the pharmacy level,

which could result in low or unfair pharmacy reimbursements and ultimately exacerbate pharmacy

access issues. OHA staff reported several other risks relating to these types of procurements. For a

reverse auction to be successful it is essential that all requirements be clearly defined and

communicated. Any contract OHA considers should include pharmacy protections to ensure adequate

pharmacy access is available to all Medicaid patients.

Pros: Reverse auction Cons: Reverse auction

•

Potential cost savings

• Leverages free market competition

• Ability to define contract requirements

bidders must meet

•

Less flexible and additional costs may be

incurred with change orders

• Provider uncertainty between contract

terms

• Upfront procurement costs

In recent reports, the Prescription Drug Affordability Board and the Prescription Drug Price

Transparency Program mention centralized prescription drug purchasing programs. A centralized

prescription drug purchasing program would allow Oregon to privatize, standardize, and condense drug

programs currently run by multiple state insurers to improve cost-effectiveness while retaining

oversight, control, and accountability. This would also increase buying power by aggregating the

covered lives of those insurers and programs.

A few states currently have designated agencies that coordinate the purchase of drugs for state-run

facilities and programs. Programs in Washington and Louisiana purchase drugs related to certain

conditions like hepatitis C. Massachusetts’s program administers pharmacy services for corrections,

29

See the National Academy for State Health Policy’s article on PBM reverse auctions.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 28

developmental services, mental health, among others, but does not extend to Medicaid or state

employee insurers. One state that currently has a comprehensive purchasing program for all state

insurers and state-run facilities is California. In 2019, California’s governor consolidated the drug

purchasing of all state-run programs including the California Public Employees’ Retirement System,

Medicaid, and the California Corrections Department. The California Legislative Analyst’s Office has

estimated that the state could save “hundreds of millions of dollars” per year and the Governor’s office

estimates the savings at $150 million per year just for the state’s coordinated care entities. Using the

examples of other states, the legislature should explore establishing a state prescription drug

purchasing program to leverage lives covered and save tax-payer dollars.

OHA’s CCO contracting practices are not sufficient to ensure PBM

transparency and compliance

Moving to a single PBM or FFS structure will streamline OHA’s monitoring efforts and increase

transparency and efficiency; however, there are improvements OHA can implement in the meantime to

address high-risk areas such as rebate pass-through and spread pricing.

OHA relies on CCOs for monitoring and verification of PBM compliance. PBMs are subcontractors of

CCOs, and OHA does not have direct visibility into their performance, however CCO contracts allow

OHA to review records and information from the CCOs and any of their subcontractors. While OHA

improved CCO contracts in 2020 by adding PBM-specific requirements, more needs to be done to

ensure high-risk areas are monitored and contract provisions are enforced.

OHA made some improvements, but comprehensive contract provisions are still

needed

Prior to 2020, OHA’s contracts with CCOs had no PBM-specific requirements. Beginning in 2020, the

agency made significant improvements by adding certain terms to the CCO contracts. If a CCO chooses

to not use OPDP for pharmacy benefits, they must contractually require their chosen PBM to do the

following:

30

All contracts

• Pass through all rebates and other monies PBMs receive from drug manufacturers;

• Permit the CCO to perform an annual audit to ensure its PBM is compliant with

contractual requirements and is market competitive;

• Cooperate with the CCO to obtain a market check which clearly identifies data

used to compare to the PBM’s current performance;

• Renegotiate the contract if the market check determines the PBM’s performance is

1% behind the current market in cost savings;

• Make an attestation of financial and organizational accountability and a

commitment to the principle of transparency; and

• Provide full, clear, complete, and adequate disclosure to the CCO and OHA on the

services provided and all forms of income, compensation, and other payments

received or expects to receive under the subcontract with CCO.

30

This list is not all-inclusive. To see the full contract provisions, see OHA’s website.

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 29

Pass-through contracts

• Pass through all costs so payments made to a pharmacy by the PBM agree to the

amounts the CCO paid to the PBM;

Pay-for-performance contracts

• PBM shares a portion of discounted drug costs and dispensing fees with CCOs,

based on over-performance of agreed upon performance measures.

Contracts permit CCOs to perform an annual audit of their PBMs. This optional provision does not

specify areas to be audited, which leaves it open to interpretation. Mandating CCOs to obtain a yearly

independent audit of high-risk areas could help give OHA reasonable assurance contract terms are

being met. It should be noted performing an annual audit does not replace a CCO’s responsibility for

ongoing monitoring of its PBMs.

OHA has the authority to employ a variety of sanctions on CCOs, but often opts for a more

collaborative approach. OHA reported examples of providing technical assistance, instead of corrective

action, to CCOs for instances of noncompliance. While cooperative, this method may not ensure timely

accountability. Without well-defined and communicated escalations steps, it may be difficult for OHA to

proactively enforce contract compliance. OHA should add specific contract language or reference

procedures that will go into effect if CCOs and PBMs are found to be out of compliance. A move to a

single PBM or FFS model would make monitoring easier for OHA.

The Barbara Roberts Human Services building, headquarters of the Oregon Health Authority | Source: Gary Halvorson, Oregon

State Archives

Oregon Secretary of State | Report 2023-25 | August 2023 | page 30

OHA performs minimal monitoring of CCOs and PBMs

OHA’s process for monitoring CCO contracts is coordinated by the agency’s quality assurance team.

Most contract deliverables are received by the quality assurance team and then sent to subject matter

experts within OHA for review. For PBM-specific deliverables, the subject matter experts are OPDP

staff.

31