Final Report

Prepared by

Merger review in

digital and technology markets:

Insights from national case law

Viktoria H.S.E. Robertson

Competition

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Directorate-General for Competition

E-mail: comp-publications@ec.europa.eu

European Commission

B-1049 Brussels

[Catalogue number]

Merger review in

digital and technology markets:

Insights from national case law

Final report

(17 October 2022)

LEGAL NOTICE

The information and views set out in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily

reflect the official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the

data included in this study. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf

may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein.

More information on the European Union: https://european-union.europa.eu/index_en

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2022

Catalogue number: KD-04-22-317-EN-N

ISBN: 978-92-76-60451-8

DOI: 10.2763/847448

© European Union, 2022

Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.

The reproduction of the artistic material contained therein is prohibited.

Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers

to your questions about the European Union.

Freephone number (*):

00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11

(*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some

operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you).

Author: Viktoria H.S.E. Robertson

Professor and Head of the Competition Law and Digitalization Group at the Vienna University of

Economics and Business; Professor of International Antitrust Law at the University of Graz

Abstract

This Report contains an independent expert study on the national assessment of horizontal

and non-horizontal mergers in digital and technology markets. It analyses the substantive

assessment of digital and technology merger cases from selected EU Member States as

well as from a former Member State, the United Kingdom, against the background of the

growing concern about the market power of Big Tech. The Report identifies theories of

harm repeatedly relied upon in the national decisional practice, sets out remedies adopted

to address these competition concerns, and draws conclusions therefrom for merger

assessment in Europe.

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

2

Table of contents

Executive summary .......................................................................................................... 5

I. Introduction: Purpose and organisation of the Report ........................................ 11

II. Case selection ......................................................................................................... 14

1. Legal background ......................................................................................................... 14

2. Jurisdictions covered by the analysis .......................................................................... 14

3. Case selection criteria ................................................................................................... 15

4. Identification and analysis of cases .............................................................................. 18

III. A short primer on the law and economics applicable to digital merger control . 20

1. The nature of digital mergers....................................................................................... 20

2. Digital mergers and conglomerate theories of harm ................................................. 21

3. Digital mergers and digital ecosystems ....................................................................... 24

4. The appropriate legal framework for assessing digital mergers .............................. 25

IV. National digital and technology merger cases in selected EU Member States

and the UK: Quantitative insights ....................................................................... 28

V. National digital and technology merger cases in selected EU Member States

and the UK: Qualitative insights and mapping the theories of harm ................ 34

1. Horizontal theories of harm ......................................................................................... 34

i. Non-coordinated effects: Loss of an actual competitor.............................................. 35

a. Specificities of the theory of harm ................................................................................ 35

b. NCAs applying the theory of harm in digital and technology mergers ................... 35

c. Discussion ......................................................................................................................... 42

ii. Coordinated effects ..................................................................................................... 45

a. Specificities of the theory of harm ................................................................................ 45

b. NCAs applying the theory of harm in digital and technology mergers ................... 45

c. Discussion ......................................................................................................................... 45

iii. Loss of a potential competitor – non-coordinated or coordinated effects ................. 46

a. Specificities of the theory of harm ................................................................................ 46

b. NCAs applying the theory of harm in digital and technology mergers ................... 46

c. Discussion ......................................................................................................................... 49

iv. Other horizontal theories of harm .............................................................................. 50

a. Specificities of the theory of harm ................................................................................ 50

b. NCAs applying the theory of harm in digital and technology mergers ................... 50

c. Discussion ......................................................................................................................... 52

2. Vertical theories of harm .............................................................................................. 52

i. Non-coordinated effects: Input foreclosure ................................................................ 53

a. Specificities of the theory of harm ................................................................................ 53

b. NCAs applying the theory of harm in digital and technology mergers ................... 53

c. Discussion ......................................................................................................................... 59

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

3

ii. Non-coordinated effects: Customer foreclosure......................................................... 61

a. Specificities of the theory of harm ................................................................................ 61

b. NCAs applying the theory of harm in digital and technology mergers ................... 61

c. Discussion ......................................................................................................................... 63

iii. Other non-coordinated effects .................................................................................... 64

a. Specificities of the theory of harm ................................................................................ 64

b. NCAs applying the theory of harm in digital and technology mergers ................... 64

c. Discussion ......................................................................................................................... 65

iv. Coordinated effects ..................................................................................................... 66

a. Specificities of the theory of harm ................................................................................ 66

b. NCAs applying the theory of harm in digital and technology mergers ................... 66

3. Conglomerate theories of harm ................................................................................... 66

i. Non-coordinated effects: Foreclosure ........................................................................ 66

a. Specificities of the theory of harm ................................................................................ 66

b. NCAs applying the theory of harm in digital and technology mergers ................... 67

c. Discussion ......................................................................................................................... 72

ii. Coordinated effects ..................................................................................................... 73

a. Specificities of the theory of harm ................................................................................ 73

b. NCAs applying the theory of harm in digital and technology mergers ................... 73

iii. Other effects ................................................................................................................ 73

a. Specificities of the theory of harm ................................................................................ 73

b. NCAs applying the theory of harm in digital and technology mergers ................... 73

c. Discussion ......................................................................................................................... 74

4. Theories of harm largely absent in the decisional practice ....................................... 74

i. Building and reinforcing a digital ecosystem ............................................................. 74

ii. Data advantages ......................................................................................................... 77

iii. Concentration and abuse of dominance ..................................................................... 79

5. Remedies ........................................................................................................................ 80

i. Structural remedies..................................................................................................... 81

ii. Behavioural remedies: access and interoperability ................................................... 82

iii. Further types of behavioural remedies ....................................................................... 83

iv. Discussion ................................................................................................................... 86

6. Prohibition decisions ..................................................................................................... 88

VI. Conclusions ............................................................................................................ 91

References ...................................................................................................................... 94

Table of legislation and soft law documents ................................................................. 99

European Union legislation ................................................................................................... 99

National legislation ................................................................................................................ 99

European Union soft law ....................................................................................................... 99

National soft law .................................................................................................................. 100

Table of cases ............................................................................................................... 101

Australia ............................................................................................................................... 101

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

4

Austria .................................................................................................................................. 101

Bulgaria ................................................................................................................................ 101

China ..................................................................................................................................... 101

Cyprus ................................................................................................................................... 101

Czechia .................................................................................................................................. 101

Estonia .................................................................................................................................. 102

European Union ................................................................................................................... 102

France ................................................................................................................................... 103

Germany ............................................................................................................................... 103

Greece ................................................................................................................................... 104

Hungary ................................................................................................................................ 104

Ireland ................................................................................................................................... 104

Italy ....................................................................................................................................... 105

Malta ..................................................................................................................................... 105

Netherlands .......................................................................................................................... 105

Poland ................................................................................................................................... 105

Portugal ................................................................................................................................ 105

Romania ................................................................................................................................ 105

Singapore .............................................................................................................................. 106

Slovenia ................................................................................................................................. 106

Spain ..................................................................................................................................... 106

Sweden .................................................................................................................................. 106

United Kingdom ................................................................................................................... 106

United States ........................................................................................................................ 108

List of figures ............................................................................................................... 109

Annex I: 97 national cases on digital and technology mergers, coded by outcome . 110

Annex II: 69 particularly relevant national cases on digital and technology

mergers, coded by theories of harm ................................................................... 115

Annex III: Concise summaries of 69 national cases on digital and technology

mergers ............................................................................................................... 120

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

5

Executive summary

In the present Report, I provide an independent expert study on the assessment of

horizontal and non-horizontal mergers in digital and technology markets, commissioned

by the European Commission. I analyse the substantive assessment of digital and

technology merger cases from selected European Union (EU) Member States as well as

from a former Member State, the United Kingdom, against the background of the growing

concern about the market power of Big Tech. Due to the one-stop-shop principle

contained in the EU Merger Regulation 139/2004, it is possible that national merger

control and EU merger control may not be as aligned as the law and practice on anti-

competitive agreements and abuses of a dominant position. While this can give rise to

inconsistencies, it can also represent a learning opportunity to allow for best practices on

digital mergers to emerge.

I organised the Report as follows: After an introduction setting out the purpose of the

Report (Chapter I), I provide an insight into the way in which the national cases that

constitute the basis for this Report were selected (Chapter II). Then, I give a brief

overview of the law and economics applicable to digital mergers (Chapter III). Chapter

IV contains first quantitative insights from the analysis of 97 national cases. Chapter V

contains the main body of the Report and provides qualitative insights from the in-depth

analysis of 69 national digital and technology merger cases in selected EU Member States

and the United Kingdom. It focuses on theories of harm relied upon and remedies adopted

by national competition authorities. Chapter VI concludes. The Annex contains a list of

all 97 national cases analysed for this Report (Annex I), as well as a detailed coding of

69 national cases as concerns the theories of harm addressed and the remedies adopted

(Annex II). Annex III contains concise case summaries of the 69 national cases on digital

and technology mergers.

The present Report is based on a selected number of national merger cases in digital

and technology markets. Case selection criteria included the jurisdiction in which the

case was decided (EU Member State or United Kingdom), the relevant timeframe (1

January 2015 to 31 December 2021), and the digital or technology nature of the case. In

order to identify the latter, criteria such as lists of digital companies, NACE codes and

the relevant market of a case were relied upon (Chapter II).

While digital mergers are often associated with Big Tech, the digitalisation of all

aspects of business and private life has meant that digital markets and digital mergers

have proliferated. Digital platforms are building ever more comprehensive digital

ecosystems, and the question arises whether merger control is flexible enough to meet the

new anti-competitive threats that digital mergers bring with them (Chapter III).

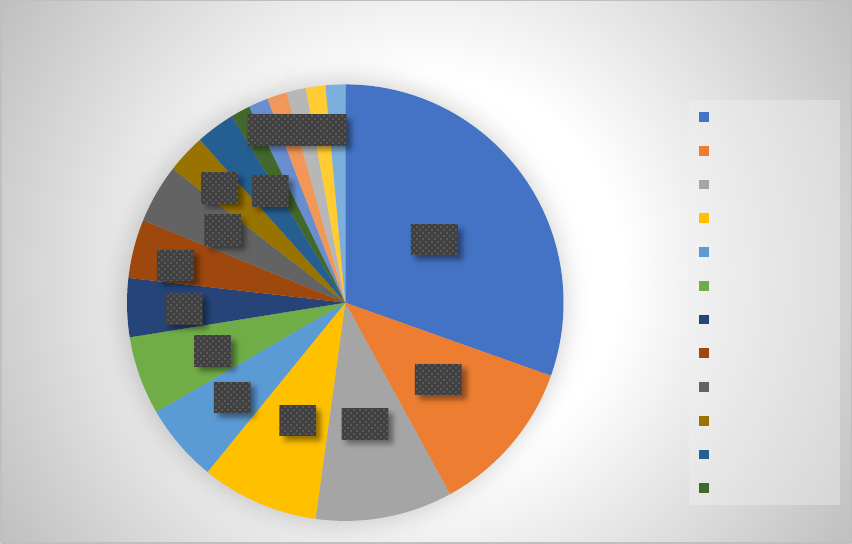

97 national digital and technology merger cases from 19 different EU Member States

and the United Kingdom, from the time period 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2021,

were assessed for the present Report (Chapter IV). A number of quantitative insights

can be drawn from this analysis. Of the 97 cases identified, 74 were unconditionally

cleared (65 in phase 1, 9 in phase 2), 15 cases were cleared subject to conditions (10 in

phase 1, 5 in phase 2), 6 concentrations were prohibited, one was withdrawn following

the national competition authority voicing serious competition concerns, and in one case

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

6

merger control was found to be inapplicable. The ratio of unconditionally cleared to

conditionally cleared or prohibited mergers already provides a first indication that most

digital and technology mergers are understood to be unproblematic by national

competition authorities.

Of the 97 cases identified, 69 cases were selected for an in-depth analysis – including

all cases that were conditionally cleared, reached phase 2, or were prohibited or

withdrawn. Based on their relevance for this Report, a number of unconditionally cleared

cases were also included in this sample. It is notable that of the 69 mergers, 30 cases (i.e.,

over 40%) exclusively assessed horizontal effects. A further 18 cases assessed horizontal

and vertical effects, while 5 cases only assessed vertical effects. 8 cases assessed

horizontal and conglomerate effects, 3 cases assessed vertical and conglomerate effects,

and 2 cases only assessed conglomerate effects. A total of 3 cases assessed horizontal,

vertical and conglomerate effects.

67%

9%

11%

5%

6%

1%

1%

97 national merger cases, by outcome

Unconditional clearance in phase 1

Unconditional clearance in phase 2

Conditional clearance in phase 1

Conditional clearance in phase 2

Prohibition

Withdrawal

Non-applicability

44%

26%

12%

4%

7%

4%

3%

69 national merger cases,

by theories of harm

Only horizontal theories of harm

Horizontal and vertical theories of harm

Horizontal and conglomerate theories of

harm

Horizontal, vertical and conglomerate

theories of harm

Only vertical theories of harm

Vertical and conglomerate theories of harm

Only conglomerate theories of harm

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

7

Of the 6 cases in which concentrations were prohibited, all cases assessed horizontal

effects, and in addition, 4 assessed vertical foreclosure effects. None assessed any

conglomerate effects. Of the 16 cases in which concentrations were conditionally cleared,

8 only related to horizontal effects and 2 only related to vertical effects. 2 further cases

related to horizontal and vertical effects, while 2 cases only related to vertical and

conglomerate effects. 2 conditional clearances related to conglomerate effects only. These

quantitative insights highlight that while conglomerate theories of harm have taken centre

stage in discussions about digital mergers, the merger practice across the European Union

is either still lagging behind these theoretical insights – or horizontal effects continue to

represent the number one concern in digital merger control.

69 national digital and technology merger cases in selected EU Member States and the

United Kingdom were relied upon for an in-depth, qualitative analysis. These cases

cover 17 different jurisdictions. To allow for more detailed insights, theories of harm were

categorised along the lines of horizontal effects (loss of an actual competitor, loss of a

potential competitor, coordinated effects, other horizontal effects), vertical effects (input

foreclosure, customer foreclosure, other vertical non-coordinated effects, coordinated

effects) and conglomerate effects (foreclosure, other conglomerate effects). It was notable

that a total of 51 cases raised issues related to the loss of an actual competitor on the

relevant market, and 9 of these mergers were cleared subject to conditions, 4 were

prohibited and one was withdrawn. Where the clearance of a merger was subject to

commitments, the latter sometimes played a role again in later cases (Just Eat/La Nevera

Roja, ES 2016). It was seen how digital markets can differ from country to country,

depending on the success of individual national platforms (e.g., see the analysis of

eBay/Adevinta in the UK, Germany and Austria, all 2021). The presence of Big Tech

companies such as Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta or Microsoft was repeatedly held to

constitute an important factor when concluding that a digital acquisition by a non-Big

Tech company did not raise competition concerns. In already concentrated online

markets, NCAs would sometimes welcome a merger because it could mean that the

market would not tip. Multi-homing by users or customers was equally seen as a ‘natural’

remedy against market tipping.

The loss of a potential competitor was brought up in 6 cases, of which 5 came from

the UK. Recently, this theory of harm was tested both before Austrian and UK courts in

the merger of Meta/Giphy (AT 2022; UK 2022). The concern here was that the acquisition

could stifle potential competition between Meta (formerly: Facebook) and GIF library

Giphy for advertising clients, as Giphy had rolled out a promising advertising service

prior to the acquisition that allowed it to monetise its services – and that could have

competed with Meta’s display advertising. While the UK Competition Appeal Tribunal

upheld the national authority’s prohibition of the merger on substance, the Austrian

Supreme Cartel Court upheld the Austrian Cartel Court’s conditional clearance of the

same concentration.

Input foreclosure was the most relied-upon vertical theory of harm in all cases

analysed. 27 cases related to this type of concern. The Swedish Swedbank

Franchise/Svensk Fastighetsförmedling case (SE 2014) about online property portal

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

8

Hemnet led to the first Swedish prohibition of a merger, also due to a concern about input

foreclosure. The Slovenian merger of Sully System/CENEJE (SI 2018) was only cleared

after commitments, as the authority was concerned that there might be input foreclosure

related to both online advertising through search engines and online price comparison. In

several cases, however, the national competition authorities concluded that vertical input

foreclosure was not a credible theory of harm based on the low market shares post-merger

and/or the competitive constraint expected from competitors that would remain active on

either the upstream or the downstream markets.

Customer foreclosure was assessed in 11 national cases. In CTS Eventim/Four Artists

(DE 2017), the German authority prohibited an acquisition based on the finding that it

would (also) have further strengthened customer foreclosure. In a further case involving

CTS Eventim (AT 2019), the Austrian authority was concerned that, post-merger, the

merged entity could engage in customer foreclosure by providing its ticketing services at

above market prices to companies outside of the CTS Eventim group. This concentration

was cleared subject to conditions. The presence of a sufficient number of competitors on

one of the relevant markets was regularly seen as a factor that could mitigate vertical

effects. Low turnover was also sometimes seen as hindering a company’s ability to

foreclose competitors.

In terms of other vertical theories of harm, the Czech authority was concerned that,

post-merger, comparison shopping site Heureka.cz could ask Rockaway’s online shops

to collect excessive amounts of data about their users, data that could then be used in the

interest of Rockaway Capital’s businesses (Rockaway Capital/Heureka, CZ 2016). In a

number of cases, the national authority also considered whether the acquirer would have

access to commercially sensitive information about competitors post-merger

(esure/Gocompare.com case, UK 2015; Sully System/CENEJE, SI 2018; Sanoma/Iddink,

NL 2019; Uber International/GPC Computer Software, UK 2021).

Conglomerate foreclosure was by far the most frequently relied-upon conglomerate

theory of harm, assessed in 15 cases. In Rockaway Capital/Heureka, the Czech authority

was concerned that, post-merger, comparison shopping site Heureka.cz would give

preferential treatment to online businesses already controlled by the acquirer (CZ 2016).

Bundling strategies combining the previously separate offerings of target and acquirer

were also regularly assessed, with a view to identifying whether or not this type of

strategy would actually be beneficial to the market. In one case, the waning importance

of an offline market meant that no harm was seen in a likely online/offline bundle (Axel

Springer/Concept Multimédia, FR 2018). Advanced Micro Devices/Xilinx (UK 2021) was

one of only two cases that exclusively focused on conglomerate effects, with no

conditions imposed. In Delivery Hero (EL 2022), an acquisition in the area of online food

platforms was only cleared subject to conditions based on conglomerate competition

concerns.

Notably, any detailed consideration of digital ecosystems remained largely absent

from the theories of harm examined in the 69 merger cases that were analysed in-depth.

While Meta/Kustomer (DE 2022) outlined conglomerate concerns related to the

strengthening of a digital ecosystem through the acquisition, the national authority

ultimately cleared it unconditionally. Competition concerns in today’s digital markets

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

9

may arise not so much because of well-defined competition issues arising in specific

relevant markets, and perhaps not even because of every single small merger that is

completed. Instead, competition concerns related to digital platforms can arise from the

combined effects of these mergers in multi-sided markets with strong network effects,

with a great many markets concerned. Furthermore, data advantages that are acquired

through a merger also require careful consideration. Data capabilities – relating to both

personal data and non-personal data – are central to success in many digital markets and

can therefore also represent a significant competitive advantage to digital platforms

operating across a diverse set of markets. In recent years, multiple aspects of access and

use of data as well as of data integration and data protection have come into play in digital

merger cases. What matters now is to consolidate the lessons learned from these analyses

in order to develop a coherent approach to assessing data aspects in digital merger control.

Finally, a more coherent interaction between merger control and abuse of dominance

in digital markets also seems like a promising avenue in order to make competition law

an even more useful tool to grasp competition concerns in digital mergers.

15 national cases involved remedies that addressed the competition concerns raised

by the national competition authority. A small number of national cases included

structural remedies, namely the divestiture of parts of a business (e.g., Dante

International/PC Garage, CZ 2016; Pug/StubHub, UK 2021; Adevinta/eBay Classifieds

Group, UK 2021). In terms of behavioural remedies, these were found much more often.

First of all, in terms of access and interoperability remedies, such were required in a

number of cases (e.g., CTS Eventim/Barracuda Holding, AT 2019; Sanoma/Iddink, NL

2019; NS Groep/Pon Netherlands, NL 2020; Meta/Giphy, AT 2022). Licenses were also

among proposed remedies that could be categorised as a sort of access remedy

(Schibsted/Milanuncios, ES 2014; not accepted in Blocket/Hemnet, SE 2016). Secondly,

a broad range of other types of behavioural remedies could be observed, including the

promise not to impose exclusivity obligations on trading partners (e.g., Just Eat/La

Nevera Roja, ES 2016; CTS Eventim/Barracuda Holding, AT 2019;

Glovoappro/Foodpanda, RO 2021), the promise not to gather excessive data (e.g.,

Rockaway Capital/Heureka, CZ 2016), or the commitment not to discriminate between

trading partners (e.g., Sully System/CENEJE, SI 2018; Meta/Giphy, AT 2022). Only two

cases on conglomerate concerns included a remedy; in Rockaway Capital/Heureka (CZ

2016), the acquirer proposed to include a clear link between Heureka.cz and other

Rockaway Capital activities on the website, and committed not to discriminate against

independent sellers. In Delivery Hero (EL 2022), the acquirer committed not to bundle

food-ordering services with restaurant-reservation, and not to use data from a platform

for targeted advertising on another absent the users’ consent.

A total of 6 concentrations were prohibited. Overall, the picture on prohibitions of

digital mergers is rather straightforward: apart from the special Hungarian case based on

media law (Magyar RTL Televízió/Central Digitális Média, HU 2017), all prohibitions

related to the loss of an actual competitor (plus, in one case, vertical customer foreclosure)

or the loss of a potential competitor plus vertical input foreclosure. This shows that

horizontal theories of harm continue to be regarded as the most credible threat to

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

10

competitive markets, also in digital environments, despite topical research showing that

conglomerate (and vertical) effects resulting from digital mergers merit closer scrutiny.

In Europe, national merger cases in digital and technology markets have proliferated

in recent years. The comparison carried out in this Report has found that the analysis by

national competition authorities still very much runs along the traditional lines of

horizontal – vertical – conglomerate effects. For the future, it could be useful to frame

theories of harm more in line with the complex and interrelated market realities that we

find in the digital environment, and thereby obtain a clearer view of the three issues that

have, so far, only been assessed in a smaller number of national cases: digital ecosystems,

data advantages and the interaction of mergers with abuse of dominance. A review of the

national decisional practice on digital and technology mergers against the background of

the European decisional practice, such as the one carried out in this Report, may be a good

starting point for further developing merger control in Europe and beyond in order to

enable it to fully capture the anti-competitive effects that certain digital mergers are

capable of producing.

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

11

I. Introduction: Purpose and organisation of the Report

(1) The present Report reviews digital

1

and technology

2

mergers in selected European

Union (EU) Member States and in the former EU Member State of the United

Kingdom and assesses the theories of harm that were identified by national

competition authorities (NCAs) in such cases. By focusing on the developing

decisional practice in digital and technology mergers at the national level, the

Report intends to provide a broad basis for the Commission’s reflection in relation

to the review of digital and technology mergers.

(2) The Call for Tenders requires that the expert advice should cover the following

issues:

(i) an identification of theories of harm devised in the decisional practice

and the concrete risks identified by NCAs,

3

and

(ii) an identification of remedies adopted by NCAs to solve these competition

concerns.

(3) Theories of harm are here understood as ‘hypothes[e]s about how the process of

rivalry could be harmed as a result of a merger’.

4

Depending on the type of merger

under investigation, a theory of harm may relate to horizontal effects, vertical

effects or conglomerate effects.

(4) I was commissioned by the European Commission to provide the expert Report

sought by its Call for Tenders, and hereby present my Report.

(5) In preparation of this Report, I have reviewed:

• the decisional practice on digital and technology mergers of NCAs of selected

Member States of the EU as well as of the United Kingdom as a former EU

Member State,

• the decisional practice of the European Commission on digital and technology

mergers,

• relevant guidance on digital and technology mergers, and

• relevant academic literature.

(6) Based on a review of hundreds of cases from all EU jurisdictions plus the United

Kingdom, I compiled a sample of 97 national merger cases from 19 jurisdictions

that I coded by outcome. Of these, I ultimately selected a sample of 69 national

cases from 17 jurisdictions for an in-depth analysis (for case selection criteria, see

Chapter II below). The Report categorises these national cases based on the types

of competition concerns that arose in digital and technology mergers

(‘mapping’). For each type of concern, I provide a general overview of the

relevant issues, give a quantitative assessment of national cases relating to the type

of concern, and then provide a more detailed qualitative analysis. In terms of the

1

For a definition of what includes digital mergers, see para (19) below.

2

For a definition of what includes technology mergers, see para (20) below.

3

The term NCA is here understood within the meaning of Article 35 of Regulation 1/2003, meaning that

certain national courts (eg, the Austrian Cartel Court) will also be regarded as NCAs for the purposes of

this Report.

4

Competition & Markets Authority, Merger Assessment Guidelines (CMA129, 18 March 2021) para 2.11.

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

12

qualitative analyses, I describe the concrete conduct, strategy or behaviour

concerned in the most relevant national cases identified, and include references to

the relevant case law and decisional practice from a comparative perspective. In

addition, for each issue and relevant illustrative case, I provide an indication of

the outcome of the merger review conducted at the national level. Competition

concerns identified by NCAs are examined and put into the context of both the

European Commission’s decisional practice and academic research on digital and

technology mergers.

(7) Where commitments or other remedies were adopted or imposed, I describe,

where available, the type of measure adopted, the main terms, ancillary

requirements, enforcement mechanisms, and duration.

(8) Concerning theories of harm, the Call for Tenders provides that the Report should

include both horizontal and non-horizontal theories of harm. As regards horizontal

theories of harm, a focus of the Report lies on identifying whether NCAs’

assessment of the mergers included competitive concerns because the buyer

viewed the target as a potential threat and bought it to either discontinue the

target’s innovation (‘killer acquisition’)

5

or incorporate it into its own portfolio

(‘zombie acquisition’). It is also assessed to what extent the importance of

acquiring data through a merger was considered by NCAs.

(9) As regards non-horizontal theories of harm, the focus of the Report lies on

identifying whether NCAs’ assessment of the mergers included competitive

concerns because of vertical or conglomerate effects that the mergers could entail.

Here, possibilities include the risk of foreclosing (potential) competitors in

various ways, eg through the degradation of interoperability or refusal to supply.

(10) The Report is structured as follows: Chapter II gives an insight into the way in

which national cases were selected, as these constitute the basis for this Report.

Chapter III sets the scene by providing an overview of the law and economics

applicable to digital mergers as discussed in the academic literature. Chapter IV

contains quantitative insights from the analysis of 97 national digital and

technology merger cases in selected Member States of the EU and in the United

Kingdom. Chapter V contains qualitative insights from the analysis of 69 national

digital and technology merger cases in selected Member States of the EU and in

the United Kingdom. It discusses various theories of harm and how they were

applied in national cases, and links them to the European decisional practice.

Chapter VI provides concise conclusions.

(11) In Annex I, I provide an overview of those 97 national cases that I consider

particularly instructive for this Report, coded by the outcome of the case. In Annex

II, I provide a list of those 69 cases that I found to be most relevant for the present

Report based on the case selection criteria (Chapter II), and each case is coded

5

On this term, which was coined in relation to mergers and acquisitions in the pharmaceutical industry, see

Colleen Cunningham, Florian Ederer & Song Ma, ‘Killer Acquisitions’ (2021) 129 Journal of Political

Economy 649.

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

13

based on the theories of harm employed in that decision. In Annex III, I provide

concise summaries of those 69 merger cases.

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

14

II. Case selection

(12) The following sets out the way in which national cases were selected for this

Report.

1. Legal background

(13) Based on the one-stop-shop principle of the European Union Merger Regulation

(Article 21 EUMR),

6

EU merger control under the auspices of the European

Commission exclusively applies to mergers that come within the jurisdiction of

the EUMR. Article 3 EUMR foresees turnover-based thresholds to decide on the

Commission’s jurisdiction.

(14) Under Article 4 para 5 EUMR, merging parties whose merger would be notifiable

in at least three Member States may make a reasoned submission asking the

Commission to review the merger. This has occurred in digital mergers.

7

Referrals

from NCAs (Article 22 EUMR) can equally lead to the European Commission

assessing a merger, as has occurred in digital markets.

8

In the case of an Article

22 EUMR referral, the Commission can review the merger with respect to the

markets of the referring Member State(s).

9

(15) While the EUMR relies on different turnover thresholds in order to separate

notifiable mergers from those that do not come within the purview of EU merger

control, some national merger control regimes – such as the Austrian

10

and

German

11

one – have introduced additional transaction value-based thresholds

that require the notification of a merger if the acquirer’s payment for the target

exceeds a certain amount.

2. Jurisdictions covered by the analysis

(16) The literature on digital and technology mergers is frequently focused on cases at

the level of the European Union,

12

or compares the EU and US approaches to

digital mergers.

13

While this focus is justified based on the overall importance of

6

Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the control of concentrations between

undertakings (EUMR) [2004] OJ L24/1.

7

Eg, see European Commission Decision of 3 October 2014, COMP/M.7217 – Facebook/WhatsApp.

8

Although this is a rare occurrence, the recent Meta/Kustomer merger was assessed in parallel by the

European Commission, following an Article 22 EUMR referral from Austria, and by the German

Bundeskartellamt; see European Commission Decision of 27 January 2022, M.10262 – Meta/Kustomer;

Bundeskartellamt, Meta/Kustomer (B6-21/22, 11 February 2022).

9

See European Commission, Commission Guidance on the application of the referral mechanism set out

in Article 22 of the Merger Regulation to certain categories of cases [2021] OJ C113/1, para 11 fn 12.

10

§ 9 para 4 Cartel Act, Austrian Federal Law Gazette I 61/2005 as amended.

11

§ 35 para 1a Act against Restraints of Competition, German Federal Law Gazette I 2013/1750 as

amended.

12

Marc Bourreau and Alexandre de Streel, ‘Digital Conglomerates and EU Competition Policy’ (CERRE

Report, March 2019); Tristan Lécuyer, ‘Digital Conglomerates and Killer Acquisitions – A Discussion of

the Competitive Effects of Start-Up Acquisitions by Digital Platforms’ (N° 1-2020) Concurrences 42.

13

Yong Lim, ‘Tech Wars: Return of the Conglomerate – Throwback or Dawn of a New Series for

Competition in the Digital Era?’ (2020) 19 Journal of Korean Law 47, 57 (speaking of ‘data-driven network

effects’). Sometimes, the UK’s approach to digital mergers is incorporated into the analysis: Anne C. Witt,

‘Who’s Afraid of Conglomerate Mergers’ (2022) 67 Antitrust Bulletin 208.

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

15

these two jurisdictions, it nevertheless risks overlooking important developments

in national merger control in EU Member States and misses out on obtaining a

broader picture on digital merger control. With the present Report, I intend to

bridge this gap by analysing digital and technology merger cases from a wider

scope of jurisdictions within the European Union, including the United Kingdom

as a former Member State.

3. Case selection criteria

(17) Cases analysed were chosen based on the following criteria:

(a) the jurisdiction in which the case was decided (EU Member State or United

Kingdom),

(b) the timeframe in which the decision was rendered (1 January 2015 to 31

December 2021), and

(c) the digital or technology nature of the markets analysed in the case.

(18) The timeframe of the Report spans 7 years, from 1 January 2015 to 31 December

2021, with a particular focus on cases emerging over the past five years. This is

due to the fact that digital mergers have proliferated during that time. Furthermore,

the premise is that the most recent cases can give the most profound insights into

adaptations in the substantive merger analysis. A small number of cases were

included that were decided prior to 1 January 2015 or after 31 December 2021,

due to a particular interest in the analysis that was carried out therein.

(19) Digital merger cases can be enormously varied. This is due to several factors.

First of all, a large number of traditional in-person services are moving online.

Second, digital platforms are intensifying their conglomeration strategies,

meaning they are moving into very varied markets ranging from movie production

to restaurant guides. In order to establish which cases should be regarded as

‘digital’ and thus assessed for this Report, a number of selection criteria were

established from multiple angles:

a) Did the case include a well-known digital platform operator? Companies in

this category included Adobe, Alphabet, Airbnb, Amazon, Apple, Activision

Blizzard, Booking.com, Deliveroo, eBay, Facebook, Google, Intuit, Meta,

Microsoft, Netflix, PayPal, Rakuten, Salesforce, Spotify, and Uber. In order

to compile this list, both the Forbes ‘Top 100 Digital Companies’ list

14

and

European case law

15

were relied upon. The focus was on digital services

14

Forbes, Top 100 Digital Companies <https://www.forbes.com/top-digital-companies/list/3/#tab:rank>.

Telecoms were excluded for the purposes of this Report.

15

In particular, decisions related to Big Tech were regarded as relevant. Big Tech is here understood as the

GAFAM companies, ie Google (Alphabet), Apple, Amazon, Facebook (Meta) and Microsoft.

Meta (formerly Facebook): European Commission Decision of 27 January 2022, M.10262 –

Meta/Kustomer (NACE M.73.1 - Advertising, J.62 - Computer programming, consultancy and related

activities, J.61.9 - Other telecommunications activities, J.63.12 - Web portals; Article 8(2) with conditions

& obligations; referral from Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Iceland, Italy, Ireland, the Netherlands,

Portugal and Romania – Germany carried out its own investigation); European Commission Decision of 3

October 2014, COMP/M.7217 – Facebook/WhatsApp (NACE M.73.1 - Advertising, J.62.09 - Other

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

16

rather than hardware, although several digital platform providers have moved

into offering hardware as well. These cases are covered by the ‘technology’

category (see below).

b) What was the NACE code related to the case? NACE codes that were

included in the digital category were identified through a comprehensive case

search of all the Big Tech mergers that the European Commission has

investigated to date.

16

NACE codes that were understood to be particularly

relevant included ‘web portals’, ‘computer programming activities’, ‘data

information technology and computer service activities, J.61.9 - Other telecommunications activities;

Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition; assessed under Article 4(5) EUMR).

Alphabet (formerly Google): European Commission Decision of 17 December 2020, M.9660 –

Google/Fitbit (NACE J.62.01 - Computer programming activities, C.26.4 - Manufacture of consumer

electronics, J.58.2 - Software publishing, J.63.12 - Web portals; Art. 8(2) with conditions & obligations);

European Commission Decision of 23 February 2016, M.7813 – Sanofi/Google/DMI JV (NACE C.21 -

Manufacture of basic pharmaceutical products and pharmaceutical preparations, C.32.5 - Manufacture of

medical and dental instruments and supplies, Q.86.9 - Other human health activities; Article 6(1)(b) Non-

opposition); European Commission Decision of 13 February 2012, COMP/M.6381 – Google/Motorola

Mobility (NACE C.26.30 - Manufacture of communication equipment, J.61 - Telecommunications, J.61.20

- Wireless telecommunications activities; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition); European Commission Decision

of 11 March 2008, COMP/M.4731 – Google/DoubleClick (NACE M.73.1 – Advertising; Article 8(1)

Compatibility).

Apple: European Commission Decision of 6 September 2018, M.8788 – Apple/Shazam (NACE M.73.1 –

Advertising, J.62 - Computer programming, consultancy and related activities, J.63.1 - Data processing,

hosting and related activities, web portals, J.63 - Information service activities; Article 8(1) Compatibility;

referral from Austria, France, Iceland, Italy, Norway, Spain and Sweden); European Commission Decision

of 25 July 2014, COMP/M.7290 – Apple/Beats (NACE C.26.4 - Manufacture of consumer electronics,

J.58.29 - Other software publishing; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition).

Microsoft: European Commission Decision of 21 December 2021, M.10290 – Microsoft/Nuance (NACE

J.62 - Computer programming, consultancy and related activities; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition);

European Commission Decision of 5 March 2021, M.10001 – Microsoft/Zenimax (NACE J.58.21 -

Publishing of computer games; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition); European Commission Decision of 19

October 2018, M.8994 – Microsoft/GitHub (NACE J.62.01 - Computer programming activities, J.63.1 -

Data processing, hosting and related activities, web portals; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition); European

Commission Decision of 6 December 2016, M.8124 – Microsoft/LinkedIn (NACE J.62 - Computer

programming, consultancy and related activities, J.63.12 - Web portals; Article 6(1)(b) with conditions &

obligations); European Commission Decision of 4 December 2012, COMP/M.7047 – Microsoft/Nokia

(NACE C.26.3 - Manufacture of communication equipment; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition); European

Commission Decision of 10 February 2012, COMP/M.6474 – GE/Microsoft/JV (NACE J.62 - Computer

programming, consultancy and related activities; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition); European Commission

Decision of 7 October 2011, COMP/M.6281 – Microsoft/Skype (NACE J.63 - Information service

activities; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition) (upheld in Case T-79/12 Cisco Systems and Messagenet v

Commission, ECLI:EU:T:2013:635); European Commission Decision of 18 February 2010,

COMP/M.5727 – Microsoft/Yahoo! Search Business (NACE J.63.1 - Data processing, hosting and related

activities, web portals; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition). Most recently, Microsoft has announced its

acquisition of game developer Activision Blizzard, and a merger filing can be expected in this case: Pietro

Lombardi and Samuel Stolton, ‘Microsoft heads for second big EU showdown — this time over gaming’

Politico (24 January 2022) <https://www.politico.eu/article/microsoft-activision-eu-showdown-video-

game/>.

Amazon: European Commission Decision of 15 March 2022, M.10349 – Amazon/MGM (NACE J.59 -

Motion picture, video and television programme production, sound recording and music publishing

activities; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition).

16

On these, see footnote 15 above.

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

17

processing, hosting and related activities’ and ‘computer programming,

consultancy and related activities’.

17

c) Was the relevant market relied upon in the case related to digital markets?

The following keywords were used as an indicator: AdTech, API, app,

application, cloud computing, display advertising, internet, Internet of

Things/IoT, marketplace, online advertising, online betting/gaming, online

communication services, personalised advertising, platform, price

comparison, software, wearable.

d) Exclusion criteria: Cases involving traditional media were excluded, unless

they primarily related to social media. Broadcasting and pay-TV cases were

also excluded.

(20) Technology merger cases were included as an additional category of cases. The

following selection criteria were established from multiple angles:

a) Did the case include a well-known high-tech company? Companies in this

category included AMD, Broadcom, Cisco, Dell, Ericsson, Huawei, IBM,

Intel, Lenovo, LG Electronics, NEC, Nintendo, Nvidia, NXP

Semiconductors, ON Semiconductor, Oracle, Qualcomm, Samsung, SAP,

Taiwan Semiconductor, Xiaomi, and ZTE. In order to compile this list, the

Forbes ‘Top 100 Digital Companies’ list,

18

the Thomson Reuters ‘Top 100

Global Tech Leaders’ list

19

and European case law

20

were relied upon. The

17

In particular, the following NACE codes were identified (if appearing in more than one case, the NACE

code is set in italics):

C.21 - Manufacture of basic pharmaceutical products and pharmaceutical preparations

C.26.3 - Manufacture of communication equipment

C.26.4 - Manufacture of consumer electronics

C.32.5 - Manufacture of medical and dental instruments and supplies

J.58.2 - Software publishing

J.58.21 - Publishing of computer games

J.58.29 - Other software publishing

J.59 - Motion picture video and television programme production, sound recording and music publishing

activities

J.61 - Telecommunications

J.61.20 - Wireless telecommunications activities

J.61.9 - Other telecommunications activities

J.62 - Computer programming, consultancy and related activities

J.62.01 - Computer programming activities

J.62.09 - Other information technology and computer service activities

J.63 - Information service activities

J.63.1 - Data processing, hosting and related activities, web portals

J.63.12 - Web portals

M.73.1 - Advertising

Q.86.9 - Other human health activities

18

Forbes, Top 100 Digital Companies <https://www.forbes.com/top-digital-companies/list/3/#tab:rank>.

19

Thomson Reuters, Top 100 Global Tech Leaders <https://www.thomsonreuters.com/en/products-

services/technology/top-100.html>.

20

AMD: European Commission Decision of 30 June 2021, COMP/M.10097 – Advanced Micro

Devices/Xilinx (NACE C.26.1 - Manufacture of electronic components and boards; Article 6(1)(b) Non-

opposition).

Broadcom: European Commission Decision of 23 November 2015, M.7686 – Avago/Broadcom (NACE

G.46.52 - Wholesale of electronic and telecommunications equipment and parts, C.26.11 - Manufacture of

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

18

focus was on hardware required for digital services. It is noteworthy that

digital platforms found in the ‘digital’ category are also often producers of

the technology they rely on, meaning they may also be considered high-tech

companies.

b) What was the NACE code related to the case? NACE codes that were

included in the technology category were identified through a case search of

important technology mergers that the European Commission has

investigated to date.

21

NACE codes that were included in the technology

category included ‘manufacture of communication equipment’, ‘manufacture

of consumer electronics’, ‘manufacture of electronic components’,

‘wholesale of electronic and telecommunications equipment and parts’ and

‘wholesale of computers, computer peripheral equipment and software’.

22

c) Was the relevant market relied upon in the case related to high-tech

markets? The following keywords were used as an indicator: chips, hardware,

patent, and semiconductor.

d) Exclusion criteria: Cases involving technology not directly relevant to

digital markets were excluded. Telecommunications operators were also

excluded.

4. Identification and analysis of cases

(21) Based on the selection and exclusion criteria set out above, a large set of cases

from across EU Member States and from the United Kingdom could be identified

electronic components, N.77.4 - Leasing of intellectual property and similar products, except copyrighted

works; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition); European Commission Decision of 12 May 2017, M.8314 –

Broadcom/Brocade (NACE C.26.3 - Manufacture of communication equipment, C.26.11 - Manufacture of

electronic components; Article 6(1)(b) with conditions & obligations); European Commission Decision of

12 October 2018, M.9054 – Broadcom/CA (NACE J.62.01 - Computer programming activities, C.26.11 -

Manufacture of electronic components; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition); European Commission Decision

of 30 October 2019, M.9538 – Broadcom/Symantec Enterprise Security Business (NACE J.62.01 -

Computer programming activities; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition).

Intel: European Commission Decision of 20 May 2021, M.10059 – SK Hynix/Intel’s Nano and SSD

Business (NACE C.26.2 - Manufacture of computers and peripheral equipment; Article 6(1)(b) Non-

opposition); European Commission Decision of 14 October 2015, M.7688 – Intel/Altera (NACE C.26.1 -

Manufacture of electronic components and boards; Article 6(1)(b) Non-opposition).

Qualcomm: European Commission Decision of 18 January 2018, M.8306 – Qualcomm/NXP

Semiconductors (NACE C.26.3 - Manufacture of communication equipment, J.62.09 - Other information

technology and computer service activities; Article 8(2) with conditions & obligations).

21

On these, see footnote 20 above.

22

In particular, the following NACE codes were identified (if appearing in more than one case, the NACE

code is set in italics):

C.26.1 - Manufacture of electronic components and boards

C.26.11 - Manufacture of electronic components

C.26.2 - Manufacture of computers and peripheral equipment

C.26.3 - Manufacture of communication equipment

G.46.52 - Wholesale of electronic and telecommunications equipment and parts

J.62.01 - Computer programming activities

J.62.09 - Other information technology and computer service activities

N.77.4 - Leasing of intellectual property and similar products, except copyrighted works

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

19

based on literature research,

23

database research

24

and outreach to colleagues from

various jurisdictions. This sample was selected after careful consideration of the

selection criteria, of the need to represent a multitude of jurisdictions, of the date

of the decision, of the case’s relevance for digital and technology markets, and of

the Report’s particular interest in cases in which remedies were adopted. From

hundreds of cases reviewed, a sample of 97 cases was derived that were

considered particularly relevant based on the factors set out above, and full text

decisions for all these cases were obtained. All relevant full text decisions are

supplied to the Directorate General for Competition together with this Report. A

list of the 97 NCA decisions identified as particularly relevant can be found in

Annex I. While this list is quite extensive, it can only represent a sample and does

not aim to be comprehensive. Rather, the intention is to represent a wide range of

digital and technology merger cases that showcase the types of cases encountered

in these sectors from a wide range of jurisdictions.

(22) The 97 decisions considered particularly relevant were then coded based on the

type of outcome that the case led to (i.e., cleared/cleared with

conditions/prohibited/withdrawn/non-applicability; phase 1/phase 2). Where a

case led to an outcome in both phase 1 and 2, only the phase 2 outcome was

included. All decisions which led to conditional clearance, a phase 2 investigation,

a prohibition or a withdrawal were selected for an in-depth analysis. A further 38

cases with unconditional clearance in phase 1 were also analysed in depth, based

on the case’s importance and the language capabilities of the expert and her

collaborators. This led to an in-depth analysis of a total of 69 cases. Annex II

provides a list of these 69 cases that identifies the theories of harm employed in

those cases. Annex III provides a concise summary of all those 69 national cases

that were considered particularly relevant for the purposes of this Report.

(23) The 69 national cases that were considered particularly relevant for the purposes

of this Report were then analysed in detail as concerns

(i) the competitive concerns raised by the NCA,

(ii) the theories of harm assessed by the NCA, and

(iii) the remedies (if any) imposed by the NCA or agreed upon between the

merging parties and the NCA.

(24) Where mergers gave rise to cases in multiple jurisdictions, such cases were

particularly focused on for comparative purposes.

23

See, especially, Daniel Mândrescu (ed), EU Competition Law and the Digital Economy: Protecting Free

and Fair Competition in an Age of Technological (R)Evolution (XXIX FIDE Congress 2020).

24

This was carried out on the Caselex.eu platform.

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

20

III. A short primer on the law and economics applicable to

digital merger control

(25) In digital and technology markets, conglomerate and vertical mergers are

increasingly coming into the focus of merger control. Conglomerate mergers are

mergers that occur between companies that are not competitors on the same

relevant market, while vertical mergers are mergers that occur between companies

that are in a vertical relationship, eg as suppliers or customers.

25

Together, these

types of mergers will be called non-horizontal mergers to distinguish them from

horizontal mergers, i.e. mergers between companies active on the same relevant

market.

26

(26) The reason for this renewed interest in non-horizontal mergers can be seen in the

specific characteristics that dynamic, digital markets display and that have an

influence on how digital companies compete.

27

This interest in digital mergers

was only heightened by the unprecedented ‘buying spree’ on which a number of

digital platforms embarked over the past years,

28

leading to noteworthy digital

mergers that were not necessarily considered horizontal and yet understood to be

possibly harmful to competition by the public.

29

1. The nature of digital mergers

(27) Big Tech is increasingly diversifying its portfolio, creating digital ecosystems

with varied offerings for consumers. Over the past few years, the European

Commission alone has investigated well over a dozen Big Tech mergers

30

as well

as an important number of technology mergers, for example in the area of

25

European Commission, Guidelines on the assessment of non-horizontal mergers under the Council

Regulation on the control of concentrations between undertakings (Non-horizontal Merger Guidelines

2008) [2008] OJ C265/6, paras 2-5, 91. The US Vertical Merger Guidelines encompass both vertical

mergers as under the European definition, as well as vertical issues that arise in mergers of complements,

ie conglomerates; US Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission, Vertical Merger Guidelines

(30 June 2020) 1.

26

On the nature of horizontal mergers, see European Commission, Guidelines on the assessment of

horizontal mergers under the Council Regulation on the control of concentrations between undertakings

(Horizontal Merger Guidelines 2004) [2004] OJ C31/5, para 5; US Department of Justice and Federal Trade

Commission, Horizontal Merger Guidelines (19 August 2010) 1.

27

For an introduction, see Viktoria H.S.E. Robertson, ‘Antitrust Law and Digital Markets’ in Heinz D.

Kurz, Marlies Schütz, Rita Strohmaier and Stella S. Zilian (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Smart

Technologies: An Economic and Social Perspective (2022) 432.

28

Alex Sherman and Lauren Feiner, ‘Amazon, Microsoft and Alphabet went on a buying spree in 2021

despite D.C.’s vow to take on Big Tech’ (22 January 2022) CNBC

<https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/22/amazon-microsoft-alphabet-set-more-deals-in-2021-than-last-10-

years.html>.

29

Eg, see Cecilia Kang and David McCabe, ‘F.T.C. Broadens Review of Tech Giants, Homing In on Their

Deals’ New York Times (11 February 2020); David McCabe and Jim Tankersley, ‘Biden Urges More

Scrutiny of Big Business, Such as Tech Giants’ New York Times (16 September 2021); Kiran Stacey, James

Fontanella-Khan and Stefania Palma, ‘Big tech companies snap up smaller rivals at record pace’ Financial

Times (19 September 2021); Richard Waters and Leo Lewis, ‘Why gaming is the new Big Tech

battleground’ Financial Times (21 January 2022).

30

For a comprehensive list of these cases, see already footnote 15 above.

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

21

semiconductors.

31

Digital and technology mergers are not restricted to Big Tech,

however. Another trend that can be noted at the merger stage is that more and

more services and retail activities are (also) moving online, something that can be

seen in travel agency services,

32

in the sale of books and household goods,

33

in

digital property listings

34

or the renting of bicycles through mobile applications,

35

as well as in online betting and gambling.

36

2. Digital mergers and conglomerate theories of harm

(28) In merger control, horizontal mergers are traditionally viewed as a bigger threat

to competition than vertical or conglomerate mergers. This is also how the

European Commission frames the issue in its 2008 Non-Horizontal Merger

Guidelines.

37

The 2021 Merger Guidelines by the UK’s Competition & Markets

Authority highlight that over 80% of its merger investigations in phase 1 relate to

horizontal mergers.

38

In this assessment, however, digital market environments

with their specific market characteristics may be a game-changer.

39

(29) In digital markets, mergers often defy traditional categorisations because a merger

may at the same time be a vertical merger (where the data from an acquired start-

up serves as an additional input), a conglomerate merger (where an aspect of an

acquired start-up complements the offerings of the acquiring platform) and a

horizontal merger (where an aspect of an acquired start-up already competes with

the acquiring platform’s offerings).

40

(30) After a considerable conglomerate merger wave in the 1960s and 1970s,

41

conglomerate mergers have today returned to the forefront of antitrust debate.

31

For a comprehensive list of these cases, see already footnote 20 above.

32

Office of Fair Trading, Web Reservations/Hostelbookers.com (ME/6062/13, 2 August 2013).

33

Autorité de la concurrence, Fnac/Darty (16-DCC-111, 27 July 2016).

34

Bundeskartellamt, Axel Springer/Immowelt (B6-39/15, 20 April 2015); Competition & Markets

Authority, ZPG/Websky (ME/6690/17, 29 June 2017); Autorité de la concurrence, Axel Springer/Concept

Multimédia (18-DCC-18, 1 February 2018).

35

Autoriteit Consument & Markt, NS Groep/Pon Netherlands (ACM/20/038614, 20 May 2020).

36

Eg, see Malta Competition and Consumer Affairs Authority, GVC Holdings/Ladbrokes Coral Group

(COMP-MCCAA/4/18, 21 March 2018); Competition and Consumer Protection Commission, Stars

Group/Sky Betting & Gaming (M/18/038, 18 June 2018); Competition and Consumer Protection

Commission, Flutter Entertainment/Stars Group (M/20/001, 12 May 2020).

37

European Commission, Non-horizontal Merger Guidelines 2008, para 92.

38

Competition & Markets Authority, Merger Assessment Guidelines 2021, para 1.10.

39

On these characteristics, see also Lear, ‘Ex-post Assessment of Merger Control Decisions in Digital

Markets’ (9 May 2019) 3 ff.

40

For instance, in the recently cleared Microsoft/Nuance acquisition, the European Commission identified

and assessed ‘horizontal overlaps between the activities of Nuance and Microsoft in the markets for

transcription software’, a ‘vertical link between Microsoft’s cloud computing and Nuance’s downstream

transcription software for healthcare’, ‘conglomerate links between Nuance's transcription software

products and a number of Microsoft’s products’ and the ‘use of data transcribed with Nuance’s software’;

European Commission Decision of 21 December 2021, M.10290 – Microsoft/Nuance; European

Commission, ‘Mergers: Commission approves acquisition of Nuance by Microsoft’ IP/21/7067 (21

December 2021).

41

Eg, see Everette Macintyre, ‘Statement on Conglomerate Mergers and Antitrust Laws’ (2 December

1966)

<https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/683731/19661202_macintyre_conglome

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

22

This comeback, it has been argued, is due to the competitive characteristics found

in digital markets, as well as the platform business model popular in that market

environment and the network effects specific to some of those markets.

42

(31) In the 1970s, several theories were advanced on the reasons for conglomerate

mergers. Of these, some still appear relevant in order to understand the intentions

behind digital conglomerate mergers, in particular the market power theory and

the resource theory.

43

Under the market power theory, digital platforms move into

adjacent markets in order to strengthen their stronghold on the initial market.

Under the resource theory, the resources that digital platforms readily have

available allow them to move into adjacent markets with relative ease.

44

(32) In addition, multiple authors have identified factors that specifically explain the

reasons for digital conglomeration that go beyond how conglomerate mergers of

the 1960s and 1970s were understood.

45

These factors directly relate to possible

theories of harm under a substantive merger analysis. Lim (2020), for instance,

argues that while digital conglomeration continues to serve the goal of

diversification, this is ultimately ‘pursued more in fear of displacement rather than

business cyclicality’.

46

(33) Conglomerate mergers in the digital age can bring about a multitude of benefits

for the acquiring platform and its customers, but these benefits can at the same

time constitute new barriers to entry for innovators. On the supply-side, Bourreau

and de Streel (2019) find that the modular design of many digital products allows

digital platforms to make use of their resources for a variety of different purposes,

leading to significant economies of scope. Resources can relate to hardware,

software or data,

47

for instance. On the demand-side, digital platforms can benefit

from consumption synergies that consumers enjoy in multi-product ecosystems.

48

This can directly benefit consumers while at the same time locking them into a

particular digital ecosystem and thereby, in the long run, softening competition.

(34) While tying and bundling are generally recognised as possible anti-competitive

effects of conglomerate mergers, and thus a possibility to be assessed in the

merger review,

49

Bourreau and de Streel (2019) argue that ‘the specific

characteristics of the digital industries may change the effects of conglomerate

diversification and affect the balance between pro- and anti-competitive effects’.

50

They propose that tying and bundling, also through digital ecosystems, need to be

focused on in digital merger control as a particular barrier to entry for innovating

rate_mergers_and_antitrust_laws.pdf>. Conglomerate mergers were then addressed by the 1968 US Merger

Guidelines; US Department of Justice, Merger Guidelines (1968), section III.

42

Lim (n 13) 48.

43

Bourreau and de Streel (n 12) 6 ff.

44

Bourreau and de Streel (n 12) 7 (containing further references).

45

See, in particular, Bourreau and de Streel (n 12); Lim (n 13).

46

Lim (n 13) 55 (containing references to that effect).

47

On the particular importance of data for the analysis of conglomerate mergers, see also Lim (n 13) 57

(speaking of ‘data-driven network effects’); Lécuyer (n 12) 47.

48

Bourreau and de Streel (n 12) 9-13.

49

See European Commission, Non-Horizontal Merger Guidelines 2008, para 93.

50

Bourreau and de Streel (n 12) 13.

Merger review in digital and technology markets: Insights from national case law

23

newcomers.

51

Particular issues they draw attention to include the softening of

competition through increased differentiation and platform envelopment,

whereby ‘a dominant platform enters a new market pioneered by an entrant

platform and forecloses the new entrant’.

52

Here, the issue from a competition law

point of view is that once another company’s product is incorporated into the

buyer’s digital ecosystem, network effects may be able to further strengthen its

market power.

53

Platform envelopment has been described as a possible point of

entry for digital platforms that does not involve ‘offer[ing] revolutionary

functionality to win substantial market share’.

54

(35) While so-called portfolio effects already worried competition authorities in non-

digital cases,

55

digital conglomerates may rely on product proliferation in a

targeted way as a deterrence strategy to keep potential entrants out of the market.

56

Furthermore, digital conglomerates may sometimes act as a gatekeeper for access

to users as well as for access to products and services,

57

a fact that merger control

needs to bear in mind. Where a digital conglomerate keeps an essential component

to itself, access remedies may be appropriate.

58

(36) Pre-emption of potential competitors has been identified as an important driving

force behind digital platforms that buy promising start-ups.

59