This paper was written by a panel of

independent and academic human

rights researchers and activists

in the Philippines under the Civic

Futures initiative. It was supported

by the Fund for Global Human

Rights and Active Vista Center Inc.

and edited by Paulynn Sicam.

About the Authors

(in order of the chapters)

Marc Batac is a peacebuilder, organizer,

researcher, and political science graduate

of the University of the Philippines-Diliman.

He is currently aliated with Mindanao-based

Initiatives for International Dialogue and previously

with the Global Partnership for the Prevention of

Armed Conflict-Southeast Asia. He co-authored

“An Explosive Cocktail – Counter-terrorism,

militarization and authoritarianism in the

Philippines” (2021), and has written for Al Jazeera,

Just Security, and IPI Global Observatory.

The Ateneo Human Rights Center (AHRC) is a

Manila-based university institution engaged in

the promotion and protection of human rights.

Founded in 1986, its mission is to respect, protect

and promote human rights through engagement

with communities and partner organizations,

human rights training and education, research,

publication, curriculum development, legislative

advocacy, and policy initiatives on human rights.

Ray Paolo J. Santiago is the Executive

Director of the AHRC and the Secretary-

General of the Working Group for an ASEAN

Human Rights Mechanism. He is active in

litigation involving cases aecting vulnerable

groups, particularly women, children, urban

poor, and peasants. He has been a member

of the Ateneo Law Faculty since 2003.

Marianne Carmel B. Agunoy is the Internship

Director of the AHRC and coordinator for

student formation of the Ateneo Law School.

Maria Paula S. Villarin is a sta lawyer

at the AHRC and program manager of

the Working Group for an ASEAN Human

Rights Mechanism.

Maria Araceli B. Mancia is a project

assistant at the AHRC.

Mary Jane N. Real is feminist and human rights

advocate. She was a founding Co-Lead of Urgent

Action Fund for Women’s Human Rights Asia and

Pacic (UAF A&P), and in various capacities,

she has been involved in setting up and running

initiatives and organizations to support activists

and their movements worldwide.

Jessamine Pacis is a researcher, writer, and digital

rights advocate. She works mostly in the areas of

privacy and data protection and has participated

in projects related to digital labor, cybercrime, and

freedom of expression. She has a bachelor’s degree

in Broadcast Communication and Juris Doctor

credits from the University of the Philippines.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following organizations, human rights defenders, and academe, including

those not listed for their safety and security, for their review and feedback on rst draft of the research:

Foundation for Media Alternatives (FMA)

iDefend

KARAPATAN

Karl Arvin F. Hapal - Assistant Professor

College of Social Work and Community Development

University of the Philippines, Diliman

National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL)

No Box Philippines

Philippine Alliance of Human Rights advocate (PAHRA)

Resbak

Ria Landingin, Lunas Collective

Ritz Lee Santos III

The Women’s Legal and Human Rights Bureau, Inc., (WLB)

2 |

ACC ASEAN Coordinating Council

ACMM ASEAN Center of Military

Medicine

AFP Armed Forces of the Philippines

AHW Alliance of Health Workers

AMLC Anti-Money Laundering Council

AML/CTF Anti-Money Laundering and

Counter-Terrorist Financing

APG Asia/Pacic Group on Money

Laundering

ASEAN Association of Southeast

Asian Nations

ASG Abu Sayyaf Group

ATA Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020

ATC Anti-Terrorism Council

CA Court of Appeals

CAFGU Citizen Armed Force

Geographical Units

CBCP Catholic Bishops’ Conference

of the Philippines

CHED Commission on Higher Education

CHR Commission on Human Rights

COIN Counterinsurgency

COMELEC Commission on Elections

COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease 2019

CPP Communist Party

of the Philippines

CSO Civil Society Organization

CT Counterterrorism

CVE Countering Violent Extremism

CTED Counter Terrorism Executive

Directorate

DDB Dangerous Drugs Board

of the Philippines

DDB-DIAL Dangerous Drugs Board Drug

Information Action Line

DepEd Department of Education

DFA Department of Foreign Aairs

DILG Department of Interior and

Local Government

DND Department of National Defense

DOH Department of Health

DOJ Department of Justice

DOLE Department of Labor and

Employment

DSWD Department of Social Welfare

and Development

ECQ Enhanced Community Quarantine

EJK Extrajudicial Killing

FATF Financial Action Task Force

FICS Funders Initiative for Civil Society

FGHR Fund for Global Human Rights

FLAG Free Legal Assistance Group

GCQ General Community Quarantine

GRP Government of the Republic

of the Philippines

GWoT Global War on Terror

HRC UN Human Rights Council

HSA Human Security Act of 2007

HVT High Value Target

IATF-EID Inter-Agency Task Force on

Emerging Infectious Diseases

ICAD Inter-agency Committee

on Anti-Illegal Drugs

ICC International Criminal Court

ICJ International Commission

of Jurists

Abbreviations and Acronyms

3 |

IDADIN Integrated Drug Abuse Data

and Information Network

IHL International Humanitarian Law

IHRL International Human Rights Law

IID Initiatives for International

Dialogue

IP Indigenous People

IS/ISIL Islamic State/Daesh

ISP Independent Service Providers

JTF Joint Task Force COVID-19

KWF Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino

LGU Local Government Unit

MAG Medical Action Group

MECQ Modied Enhanced Community

Quarantine

MGCQ Modied General Community

Quarantine

MILF Moro Islamic Liberation Front

MNLF Moro National Liberation Front

NADPA National Anti-Drug Program

of Action

NADS National Anti-Drug Strategy

NAP COVID-19 National Action Plan against

COVID-19

NAP P/CVE National Action Plan on

Preventing and Countering

Violent Extremism

NAF COVID-19 National Task Force Against

COVID-19

NBI National Bureau of Investigation

NDF/NDFP National Democratic Front

of the Philippines

NDRRMC National Disaster Risk Reduction

and Management Council

NGO Non-Government Organization

NICA National Intelligence

Coordinating Agency

NPA New People’s Army

NPC National Privacy Commission

NPO Non-Prot Organizations

NSA National Security Adviser

NSC National Security Council

NTC National Telecommunications

Commission

NTF-ELCAC National Task Force to End Local

Communist Armed Conflict

NUPL National Union of

Peoples’ Lawyers

OHCHR Oce of the High

Commissioner for Human Rights

OPAPP Oce of the Presidential

Adviser on the Peace Process

OSG Oce of the Solicitor General

PAHRA Philippine Alliance of Human

Rights Advocates

PCO Presidential Communication

Oce

P/CVE Preventing and Countering

Violent Extremism

PDITR+V Prevent-Detect-Isolate-

Treat-Reintegrate plus

Vaccinate strategy

PNA Philippine News Agency

PNP Philippine National Police

PTV People’s Television Network

PWUD Persons Who Use Drugs

SC Supreme Court

SEC Securities and Exchange

Commission

TFPSA Terrorism Financing Prevention

and Suppression Act of 2012

TSP Telecommunications Service

Providers

UN United Nations

UNJP UN Joint Program

on Human Rights

UNODC UN Oce on Drugs and Crime

UNOCT UN Oce of Counter-Terrorism

WHO World Health Organization

4 |

Contents

5 |

6

Introduction

11

Counterinsurgency, Red-Tagging & The

‘War on Terror’: A War against Deliberation

and Dissent, A War with No End

61

The Eect of the Philippine

‘War on Drugs’ on Civic Space

122

Big Brother’s Grand Plan: A Look

at the Digital Security Playbook

in the Philippines

155

Conclusions: Redening Civic Space and

Building New Pathways of Resistance

85

Not Safe: Securitization of the

COVID-19 Crisis and its Impact

on Civic Space in the Philippines

Introduction

In May 2020, a global review of

the future of civic space

1

led by the

Funders Initiative for Civil Society

(FICS) found that over the last

two decades, a rapidly expanding

oppressive state and transnational

security interests and architecture,

characterized by three-fold

tactics of a “security playbook”

— the proliferation and misuse

of counterterrorism and security

laws, policies and measures;

communication and information

technologies; and toxic security

narratives – has emerged as a

dominant driver of shrinking civic

space in the decade ahead.

2

1 CIVICUS denes civic space as “the place, physical, virtual, and legal, where people exercise their rights to freedom

of association, expression, and peaceful assembly… A robust and protected civic space forms the cornerstone of

accountable, responsive democratic governance and stable societies”. On the other hand, FICS denes it as “the physical,

digital, and legal conditions through which progressive movements and their allies organize, participate, and create change”

and OHCHR denes it as “the environment that enables civil society to play a role in political, economic and social life. In

particular, civic space allows individuals and groups to contribute to policy-making that aects their lives, including how

it is implemented.” For a more critical discussion of the concept of shrinking space see the ‘Conclusions: Redening Civic

Space and Building New Pathways of Resistance’.

2 Ben Hayes and Joshi Poonam, ‘Rethinking civic space in an age of intersectional crises,’ Funders Initiative for Civil Society

(May 2020). https://global-dialogue.org/rethinking-civic-space/

3 For this paper, we use the OHCHR denition of civil society as “individuals and groups who voluntarily engage in forms of

public participation and action around shared interests, purposes or values that are compatible with the goals of the UN: the

maintenance of peace and security, the realization of development, and the promotion and respect of human rights”. This

denition goes beyond registered NGOs to encompass movements, unions, informal groups, journalists, bloggers, academics,

individual citizens engaging in participation or activism including through protest, on or oline dissent, and direct action.

Governments, at times aided by corporations,

far right, and religious conservative movements,

use this security playbook to create a hostile

environment for civil society actors working to

promote democracy and human rights and to

demand accountability from the most powerful

actors in our societies.

For the most part, civil society

3

and people’s

movements, and their supporters, have largely

taken a reactive and defensive posture that, while

critical to protect activists, has been insucient

to safeguard their civic space. There is huge space

for improvement of collaboration for a cohesive,

eective, and long-term response to counter this

trend at the transnational, regional, and domestic

levels. To address this gap, FICS and the Fund

for Global Human Rights (FGHR) launched Civic

Futures, an initiative to help tip the scales in favor

of civil society, by mobilizing the philanthropic

community to equip civil society and movement

actors to work together and across multiple issue

areas in pushing back against the overreach of the

powers of national security and counterterrorism.

by Marc Batac and the Civic Futures – Philippines Research Team

6 |

The Philippines was one of the areas identied

where the security playbook is used to restrict

civic space, suppress dissent, and target diverse

movements, and where opportunities may exist

to disrupt, reform, and—over the long-term—

transform the situation.

4

Independent and

academic human rights researchers and activists

in the Philippines, with the support of the Fund

for Global Human Rights and Active Vista,

formed a research team to better understand

how the transnational security architecture

and the use of the security playbook manifest

in the national context, and the kind of support

local and national civic actors need to address

this eectively.

Methodology and Limitations

The scope of this research is ambitious, so

a sequenced approach was envisioned. This

rst phase is a desk study that sets a baseline

of information and analyses on the dierent

aspects of this security architecture and its

impact in the Philippines. The research was

designed as a collaborative study among

a team of researchers, with each one focused

on specic and dierent aspects of the security

architecture and its impact in the Philippines.

The research team conducted an extensive

review of scholarly work and existing policy

documents, followed by a validation workshop

with various groups representing the diverse

geographic, sectoral, and ideological spectrum

of civil society in the Philippines.

4 Aries Arugay, Marc Batac & Jordan Street, ‘An Explosive Cocktail – Counter-terrorism, militarization and authoritarianism

in the Philippines’, Initiatives for International Dialogue and Saferworld (June 2021). https://iidnet.org/an-explosive-

cocktail-counter-terrorism-militarisation-and-authoritarianism-in-the-philippines/

A second phase will develop an approach to

engage and involve grassroots and local groups

in a follow-up process to ll in information gaps

in the rst phase, and to support a collective

and candid reflection and analyses of existing

civil society approaches to counter the closing

of civic space. This sequenced approach with

engagement among grassroots communities is

set to ensure that the research, its methodologies

and approaches, will not simply remain a scholarly

undertaking, but more importantly, contribute

directly towards strengthening movements and

nurturing civic space in the Philippines.

7 |

Scope

This study focuses on areas where the impact of

securitization on civic space are most apparent,

and where the Philippine government has waged

contiguous wars in the name of “security”: the

“War on Terror”, the “War on Drugs”, and the

“War on COVID-19”. This study primarily covers

the six-year administration of President Rodrigo

Duterte (2016-2022), but it also touches on

the administrations of previous presidents

and emerging developments under President

Ferdinand Marcos Jr. While President Duterte

played a key role in escalating the war rhetoric

and setting an atmosphere of impunity, this trend

preceded his administration, and the actors

that enabled this security playbook go beyond

Duterte. This inquiry is therefore relevant even

under the new Marcos Jr. administration which,

in many ways, has not altered the policies and

practices of the Duterte government that are

repressive of civic space. Rather, it has continued

the security playbook of its predecessor.

This study focuses on

areas where the impact of

securitization on civic space

are most apparent, and where

the Philippine government has

waged contiguous wars in the

name of “security”: the “War

on Terror”, the “War on Drugs”,

and the “War on COVID-19”.

Through a desk study, the research panel

aimed to provide an analysis of:

1. the nature and harmful impacts on civic

space of the misuse or abuse of security

laws and policy measures, information and

communication technologies, and narratives

used to justify repressive acts under the broad

mantle of national security in the Philippines;

2. the landscape of actors and initiatives

working at the intersection of security

and civic space; and

3. the outliers and new actors developing

alternatives, and potential entry points

and strategies for countering and reversing

these harms.

In the rst chapter on the “War on Terror”,

Marc Batac dives deep into the impact of

counterinsurgency and counterterrorism

on civic space across dierent presidential

administrations in the Philippines. The

chapter traces the long history of both the

counterinsurgency and counterterrorism

approaches, which have evolved and become

entangled with each other over the years.

These mixed militarized approaches to address

internal armed conflicts were wielded by

various administrations, including the Duterte

government, drastically contributing to the

shrinking of civic space in the country. It has

legitimized the practice of “red-tagging”,

which has become a serious threat to silence

civil society by labelling its members “enemies

of the State”. This chapter, as well as the other

chapters, demonstrates how the government

has employed legal means or subverted legal

norms to repress and undermine strategies of

dissent and deliberation, including human rights

activism, humanitarian work, and peace building.

8 |

In the second chapter, the Ateneo Human Rights

Center looks back at former President Rodrigo

Duterte’s “War on Drugs” and its detrimental

repercussions on the defense of human rights.

It provides a comprehensive account of how

the drug war, anchored on collective fear and

shame, harmed not only drug personalities

targeted for extrajudicial killings, but also human

rights defenders and activists who came to

their defense. The legal and moral space for

civil society to carry out its activism for human

rights has become much narrower in the context

of this drug war, normalizing the government’s

securitized response to the drug problem and its

consequent clamp down on civic space. As the

chapter describes, the popularization of Duterte’s

violent anti-drug rhetoric impacted civic space

through the “dangerous ction” that human rights

defenders are drug coddlers and crime enablers.

In the third chapter, on the “War on COVID-19”,

Mary Jane Real probes the securitized response

of the Philippine government to the COVID-19

health crisis. The chapter demonstrates the

links between the Philippine government’s

highly militarized and securitized pandemic

response and the shrinking civic space in

the country. In this context, the government

stretched what could be deemed acceptable

and non-acceptable by the public as far as the

curtailment of their fundamental freedoms is

concerned. The government stressed the need

to safeguard the public’s human right to health

and asserted that consequent violations of their

freedom of expression, freedom of peaceful

assembly, and other rights is essential for the

upkeep of civic space, and necessary to keep

the public safe. Further posing the pandemic

not only as a health risk, but also as a security

threat became a justication for the curtailment

of fundamental freedoms and a cover for

the persistent human rights violations being

committed with impunity in the country.

Finally, in the fourth chapter, Jessamine Pacis

focuses on securitization in digital spaces and

threats related to the use of information and

communications technology that crosscut

these “three wars”. The chapter on information

technology and the media describes the

Philippine government’s digital security

playbook, which uses legal and technical

structures to quell dissent through surveillance,

censorship, and securitized responses to

disinformation. It brings together analyses of the

war narratives peddled by the government that

paved the way for its increasing restrictions on

civic space as activism for human rights spread

rapidly into the digital terrain, especially during

the COVID-19 crisis. Through the proliferation

of the use of digital tools for surveillance and

censorship and attempts to silence independent

sources of information in traditional and social

media, President Duterte was able to control the

narrative that justied the vilication of activists

and those critical of the government.

The research team’s ultimate goal is to ensure

that civil society thrives in conditions that are

free from unjustied limitations brought about

by narrow and injurious concepts of “security”

as dened and weaponized by a few at the top—

by elites, governments and corporations—and to

nurture civic spaces in order to facilitate creative

and humane solutions to our common societal

problems. The team aspires to generate debates

to redene conceptions of “security” and “civic

space” to reflect the needs, potentials and

aspirations of all peoples, especially those

who are most aected.

Therefore, beyond naming the problem and the

incentives and motivations that underpin this

oppressive security architecture, the research

team aims for this study to inspire grassroots

organizations and their movements to deepen

and transform their strategies of resistance

against the government’s security architecture,

and create new pathways to protect and

expand civic space.

9 |

Towards this, all four chapters identify civil

society and community responses that point to

alternative and feminist practices and meanings

of security, and analyze potential challenges

and entry points under the new Ferdinand Marcos

Jr. presidency and beyond. Batac documents

alternative feminist and peacebuilding paths

to addressing the armed insurgency, such as

the indigenous people-led convergence Lumad

Husay, and other multi-sectoral initiatives for

independent spaces for deliberation and citizens’

agenda on peace and security. AHRC maps

various eorts to push back on the drug war,

such as RESBAK and Nightcrawlers, and their use

of their craft and art to shed light on and engage

the dehumanizing narratives underpinning the

drug war, and eorts on changing policy away

from approaches focused on incarceration,

and rehabilitation towards harm reduction and

public health. Real celebrates the emergence

of community platforms of care amidst the

pandemic, such as the tide of community

pantries and mutual aid, and the virtual-based

initiative Lunas Collective – both volunteer-

and women-driven. Finally, Pacis cites hashtag

campaigns reclaiming online spaces and

shedding light on misogyny and abuse, and

civil society-led cyber incident responses

to cyberattacks, among others.

Rather than being denitive and exhaustive,

this research from the rst phase is intended to

serve as a compilation of think pieces to inform

and prompt further analysis and strategizing.

There are more alternative pathways towards

change, and ideas and practices of security in

many activist and civil society spaces than the

research team could possibly map and document

in a few months. Ultimately, our hope is that

this study will be received within the Philippine

people’s movement and civil society, rst, as

a love letter for their courage, fortitude and

ingenuity; and second, as an invitation to join

and handhold in a shared and renewed journey

of hope, solidarity and reimagining.

Our hope is that this study

will be received within the

Philippine people’s movement

and civil society, rst, as a

love letter for their courage,

fortitude and ingenuity; and

second, as an invitation to

join and handhold in a shared

and renewed journey of hope,

solidarity and reimagining.

10 |

Counterinsurgency,

Red-Tagging & The

‘War on Terror’: A War

against Deliberation

and Dissent, A War

with No End

Marc Batac

11 |

I. Introduction

The Philippines has experienced decades of

armed conflict involving a number of dierent

movements with distinct grievances and

aspirations, including self-determination

struggles (notably the Cordillera and Moro

Muslim movements) and a long-running

communist armed insurgency. While the violence

peaked in the late 1960s and into the 70s and

80s, the underlying conflicts have deep-seated

causes going back to the Spanish colonial era

and continued by post-colonial, oligarchic

governments. Civilian approaches to internal

conflicts, such as peace agreements with some

armed groups, increased social services and

some structural and policy reforms, have been

welcome developments. However, the continuing

unequal access to development and socio-

economic and political life, the culture of impunity

within government and across society, and the

dominance of military and autocratic approaches

to quell grievances and dissent, undermine and

even reverse any incremental progress achieved

through peace talks and policy reforms.

This paper does not seek to delve into all existing

internal conflicts and counterinsurgency (COIN)

strategies in the Philippines, rather it is focused

on the evolution and mixing of the government’s

counterinsurgency and counterterrorism (CT)

approach to the Communist Party of the

Philippines-New People’s Army (CPP-NPA). It is

focused on the conflict with the CPP-NPA as an

analytical jump-o point, for two reasons. First,

the repressive government policies, narratives

and behavior that animate and sustain recent

trends of red-tagging, political violence and

overall erosion of civic space in the country,

are underpinned, shaped and sustained by

pernicious security narratives about the

supposed threat from the so-called “communist-

terrorist groups.” And second, the fusion of COIN

and CT rhetoric can be better understood and

observed alongside the development of the

Philippine government’s relationship with

and reaction to the CPP-NPA.

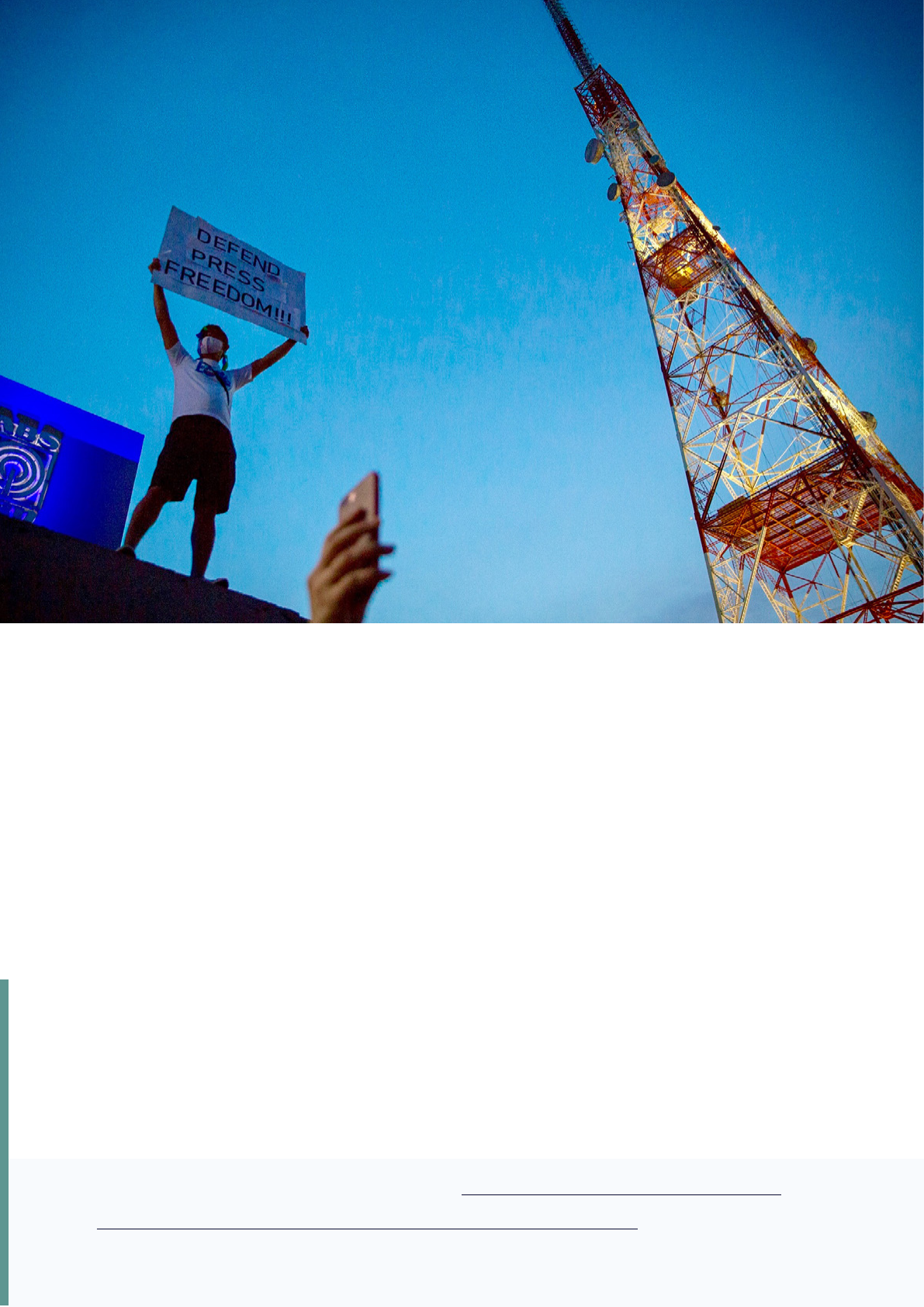

Source: IndustriALL Global Union,

Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Philippines protests, Global Day

of Action against red tagging.

12 |

In this chapter, I argue, rst, that the long-

standing COIN framework has blurred the

distinction between combatants and non-

combatants; and that despite attempts at

peacebuilding and civilian approaches, the

government’s COIN approach has relegated

politically negotiated settlement as secondary

only to the military and war-making approach.

Second, despite the failure of COIN to nd

a resolution to the armed conflict, it has

been revived as a CT strategy due to the

confluence of interests among international

and domestic actors.

Third, mixed COIN-CT measures are then

wielded not only against combatants but also

against perceived supporters and sympathizers,

activists, legal cause-oriented groups, and the

broad civil society. This has led to sustained

state-enabled red-tagging, harassment and

various forms of violations of human rights

and freedoms of citizens and communities,

and the overall shrinking of civic, deliberative

and peacebuilding spaces in the country.

Fourth, I take special note of the invisible

impact of COIN-CT measures on feminist

peacemaking and peacebuilding approaches,

and humanitarian work in conflict areas.

I propose that there is a need to further unpack

and expand our understanding of civic space

to include peacemaking and peacebuilding

strategies. And nally, building on the call

of various critical scholars to go beyond

“human rights-compliant counterterrorism,” I

identify and analyze distinct but non-mutually

exclusive responses and forms of resistance and

alternatives from civil society and communities.

This research paper is not intended to be an

exhaustive mapping of pathways, but rather

an invitation for people’s movements, civil

society and allies to further discuss how else

we can make militarist, misogynistic COIN-

CT approaches superfluous and unneeded,

and reflect on what alternative and feminist

narratives and practices of safety and security

are there or are being born.

This undertaking will require us to take a

historical look at the interplay between the

military and the civilian leaders in shaping the

country’s security needs and approach. In doing

so, we will analyze how this dynamic aects the

ebbs and flows of the peace process and shapes

the government’s security playbook and military

strategy, and, in turn, how this security playbook

impacts two important elements of functioning

democracies — deliberation and dissent.

13 |

II. In Focus: the Philippine Government’s

Mixed Counterinsurgency and

Counterterrorism Approach

1 DSWD, ‘DSWD, AFP formalize partnership to strengthen delivery of programs and services for Filipinos in conflict areas,’

(19 July 2019).

2 See the next chapter on War on Drugs.

3 Rappler, ‘NTF-ELCAC releases P16 billion to 812 ‘NPA-free’ barangay’ (13 July 2021).

4 PNA, ‘Senate OKs nat’l budget including NTF-ELCAC’s P10.8-B’ (1 December 2021).

5 Karapatan, ‘“Military pork barrel:” Karapatan flags DILG’s funds for NTF-ELCAC,’ (10 November 2021).

At the outset, it is important to identify

and dene the core policy features

enabling the current government’s

counterinsurgency and counterterrorism

approaches, particularly against the

CPP-NPA. Annex I maps the breadth

of the Philippines’ security policy

architecture and the various actors

involved, including those specic

to COIN and CT. For this section,

we will focus on two elements.

First, a core feature of the government’s

existing COIN and CT strategy is

the so-called “whole-of-nation

approach” to ending the communist

armed insurgency, instituted through

President Rodrigo Duterte’s Executive

Order No. 70 (EO 70) s. 2018. EO 70

also created the National Task Force to

End Local Communist Armed Conflict

(NTF-ELCAC). Operationally, what

this does is, rst, it formalizes and

integrates the AFP’s role in the delivery

of basic social services

1

and, second,

it mobilizes and provides incentives for

various government units, especially

local governments, to use the metrics

of military success rather than of

peace and prevention.

Similar to President Duterte’s Oplan

Tokhang

2

, the NTF-ELCAC’s Support

to the Barangay Development Program,

which grants aid or reward for local

government units (LGUs) that have

been “communist-cleared”, has

provided corrupt incentives for local

chief executives and local governments

to take short-cuts in addressing the

local dimensions of the armed conflict,

favoring primarily active warfare, lethal

force and punitive approaches over

peace and development approaches.

3

The NTF-ELCAC had an approved

budget of P19.1 billion in 2021, P622.3

million in 2020, and P522 million in

2019. For 2022, the NTF-ELCAC has

an approved budget of P10.8B, from

its proposed P29.2B budget.

4

According to the human rights

watchdog, Karapatan, Regions 7, 10, 11,

12, and 13 — which received the biggest

chunk of the fund for the NTF-ELCAC’s

Barangay Development Program,

were the same regions where the most

number of politically motivated killings

and arrests occurred from the start of

President Duterte’s term in July 2016

until June 2021. As many as 206 out of

the 414 cases of politically-motivated

extrajudicial killings transpired in these

regions, while 322 out of the 487

political prisoners who were arrested

during the Duterte administration

were arrested in these same regions.

5

Case study continued on next page >>>

14 |

The other important key feature is the

move from propaganda and labeling

of the CPP-NPA as ‘communist terrorist

groups’ to formal designation and

proscription. This reframing of the

CPP-NPA from ‘insurgents’ to ‘terrorists’

is important because it enables the

mobilization of the full extent of state

resources and power to undermine the

legitimacy and restrict the activities not

only of the armed movement but also its

perceived mass bases of support. In the

past decade, the Philippines adopted

two laws that are primarily aimed at

these: (1) the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA)

of 2020

6

, which superseded the Human

Security Act (HSA) of 2007

7

, and (2)

the Terrorism Financing Prevention and

Suppression Act (TFPSA) of 2012

8

.

6 Republic Act No. 11479 (3 July 2020).

7 Republic Act No. 9372 (6 March 2007).

8 Republic Act No. 10168 (18 June 2012).

9 Rappler. ‘DOJ formally seeks court declaration of CPP-NPA as terrorists,’ (21 February 2018).

10 Under the new counter-terrorism law, the Anti-Terrorism Council (ATC), comprised of Cabinet ocials of mostly retired

generals, is empowered to unilaterally designate as ‘terrorists’ individuals and organisations, and to authorise the arrest

and detention of a person suspected of being a ‘terrorist’ – powers that are [ordinarily] reserved for the courts.

11 Rappler, ‘Supreme Court upholds with nality most of anti-terror law’ (26 April 2022).

In February 2018, the Department of

Justice (DoJ) sought to declare the

CPP-NPA as “terrorist” organizations

under the then operational HSA.

9

Following delayed progress in the courts

or, more accurately, the lack of sucient

proof for the legal designation of the

CPP-NPA as terrorists, the government

took a new tack: it changed the law. It

passed the ATA which transferred from

the judiciary to the executive branch

the power to designate individuals or

communities as “terrorists,” making

the latter immediately liable to be

arrested without warrant or charges

and be detained for up to 24 days.

10

In December 2020, the Anti-Terrorism

Council (ATC) designated the CPP-

NPA as “terrorist organizations,

associations or groups of persons.”

In June 2021, it also designated the

National Democratic Front (NDF), the

ocial representative of the CPP-

NPA to the peace talks, as a terrorist

organization. Despite an unprecedented

37 petitions against the ATA, in April

2022, the Supreme Court (SC) upheld

most of the new anti-terrorism law

as constitutional, including the ATC’s

power of designation.

11

15 |

III. The Evolution of

Counterinsurgency and

Counterterrorism in

the Philippines, and the

Confluence of Interests

of the Actors

While strategies and operation plans to address

internal security threats and insurgencies have

changed under each president — from Cory

Aquino and Fidel Ramos’ Oplan Lambat Bitag,

to Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s Bantay Laya,

Benigno ‘Noynoy’ Aquino III’s Bayanihan, and

Duterte’s Kapayapaan and Kapanatagan — these

strategies have common features. Andreopoulos,

et al. enumerates common jargon and terms

used across administrations, such as “holistic,”

“whole-of-nation” or “people-centered”

approach, and identies a common claim of

purportedly “mobilising the entire governmental

bureaucracy” alongside various sectors and

stakeholders to transform provinces influenced

by the communist insurgency as “peaceful

and ready for further development” but are,

in fact, “designed as an ‘end-game strategy’

to denitively eradicate the insurgency.”

12

12 George Andreopoulos, Nerve Macaspac and Em Galkin, ‘“Whole-of-Nation” Approach to Counterinsurgency and the

Closing of Civic Space in the Philippines’, California: Global-e Journal, University of California Santa Barbara, 14 August

2020, Volume 13, Issue 54.

13 Ibid.

Due to the diculty in defeating guerilla-style

insurgencies, the government and its military have

targeted activists, people’s organizations and civil

society groups perceived to be providing forms

of support to the armed movement, regardless

of the existence of actual proof; labeled them

as communists and terrorists as part of a wider

“war of hearts and mind” to undermine the

legitimacy and movements of their “enemies”;

and in the process, made no distinction between

armed combatants and civilians.

13

This is how

the slippery slope or, more accurately, the logic

of COIN starts with targeting armed rebels, then

targeting activists and radicals, and eventually

leads to the repression of civilian spaces for

discourse and dissent.

…the logic of COIN starts

with targeting armed rebels,

then targeting activists and

radicals, and eventually

leads to the repression

of civilian spaces for

discourse and dissent.

16 |

A. The Conflict between the Philippine

Government and the CPP-NPA: From

Marcos to Aquino

Since 1969, the Government of the Republic

of the Philippines (GRP), through the Armed

Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and the Philippine

National Police (PNP), has been battling the

Communist Party of the Philippines-New People’s

Army-National Democratic Front (CPP-NPA-

NDF or CNN), a clandestine movement waging

a guerrilla war “aiming to win the majority of the

population to seize state power and implement

a programme of reforms called ‘national

democracy with a socialist perspective.’”

14

The AFP, in particular, considers itself a

“vanguard of the modern state and a bulwark

against communist subversion.”

15

The Martial Law regime under the dictator

President Ferdinand Marcos was one of the

most vicious periods of counterinsurgency

and violence.

16

The declaration of martial rule

was, in fact, predicated on responding to the

rebellion of the CPP-NPA and the Mindanao

Independence Movement.

17

14 Jayson Lamchek, ‘Human Rights-Compliant Counterterrorism: Myth-making and Reality in the Philippines and Indonesia’,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2019), Eng, doi: 10.1017/9781108588836, p. 81. See also Dominique Caouette,

‘Persevering Revolutionaries: Armed Struggle in the 21st Century, Exploring the Revolution of the Communist Party of

the Philippines,’ Cornell University (2004); Armando Liwanag (Jose Maria Sison), ‘Brief Review of the History of the

Communist Party of the Philippines’; Kathleen Weekley, ‘The Communist Party of the Philippines, 1968–1993: A Story

of Its Theory and Practice,’ University of the Philippines Press (2001).

15 Aurel Croissant, David Kuehn, and Philip Lorenz, ‘Breaking With the Past?: Civil-Military Relations in the Emerging

Democracies of East Asia’, East-West Center, 2012.

16 Jubair Salah, ‘Bangsamoro, ‘A Nation Under Endless Tyranny’, Islamic Research Academy, 1st edition (1984). p. 134. The

Marcos dictatorship’s ill-treatment of the Bangsamoro people is highlighted by his encouragement of the creation of the

Ilaga, a Christian paramilitary group. Together with the Philippine Army, they were responsible for multiple massacres of

the Bangsamoro people, such as the Manili Massacre in 1971 and the Malisbong Masjid Massacre of 1974. It was also during

his term, particularly in 1968, that the infamous Jabidah Massacre occurred where at least 60 Muslim Filipinos undergoing

military training were killed.

17 Proclamation No. 1081, s. 1972.

18 Patricio N. Abinales, ed. ‘The Revolution Falters: The Left in Philippine Politics after 1986’. 1st ed. Cornell University Press (1996).

The downfall of the Marcos dictatorship in 1986

and the change in government headed by President

Corazon Aquino (1986-1992) saw the return of

formal democracy and the opening up of political

space. During that period, the CPP–NPA was split

between the ‘rearmists’ who insisted on pursuing

the Maoist principle of protracted war, and the

‘rejectionists’

18

who looked towards the non-

violent, political and legal contestation of power.

The Aquino administration introduced massive

constitutional reforms to democratize the political

space and introduce checks to state power,

including the founding of an independent National

Human Rights Commission. Aquino explored peace

negotiations with various armed groups, including

the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the Moro

National Liberation Front (MNLF), the Cordillera

People’s Liberation Army, and the CNN.

17 |

However, the Aquino administration was viewed

by many as “weak and fractious.” It was wracked

by several coup attempts staged by disaected

military ocers.

19

Peace talks with the CPP–NPA

collapsed in January 1987, and thereafter, the

Aquino government announced that it had given

the AFP “a free hand in waging all-out war”

against the NPA.

20

The subsequent COIN war was

underpinned by the US strategy of ‘low-intensity

conflict’, particularly its emphasis on civic action,

propaganda and psychological warfare.

21

Under

this framework, the AFP developed its “Broad

Front Strategy” that targeted the “mass base

support systems” of the CPP–NPA instead of

the regular NPA combatants which, in practice,

meant and included targeting legal, cause-

oriented organizations.

22

Despite the opening up

of political space, human rights violations soared,

especially those committed by the military and its

paramilitary forces — primarily the Citizen Armed

Force Geographical Units (CAFGU) — and the

vigilante groups they employed in the context

of COIN against the CPP–NPA.

23

19 US State Department, ‘Previous Editions of U.S. Bilateral Relations Fact Sheets/Background Notes - Philippines (10/00),’

archived content. Accessed 17 July 2022.

20 Justus M. Van der Kroef, ‘Aquino and the Communists: A Philippine Strategic Stalemate?’, World Aairs Vol. 151, no. 3

(1988): 117–29.

21 Lamchek (2019), p. 84.

22 McCoy A (2011), p. 239.

23 Anja Jetschke, ‘Human Rights and State Security: Indonesia and the Philippines’, University of Pennsylvania Press (2011),

pp. 171–98; David Kowalewski,‘Vigilante Counterinsurgency and Human Rights in the Philippines: A Statistical Analysis’

(1990) 12 Hum Rts , pp. 246–64; McCoy (2011), pp. 433–51.

24 Miriam-Coronel Ferrer, ‘Philippines National Unication Commission: National consultations and the ‘Six Paths to Peace’’,

Accord Issue 13 (December 2002). Accessed 17 July 2022.

25 Republic Act No 1700 (Anti-Subversion Act); Republic Act No 7636 (repealing the Anti-Subversion Act).

26 Republic Act No 7941 (Party-List System Act).

B. Ramos Administration:

The Fork in the Road

The Ramos Administration (1992-1998) pursued

a major shift to politically negotiated settlements

with armed groups, along with a program of

“national reconciliation.” Ramos, a retired military

general, was Vice Chief-of-Sta of the AFP under

Marcos until 1986 when he joined rebel military

and police ocers in the attempted coup-d’état

that resulted in the People Power Revolution that

booted out the dictator.

The Ramos administration revived the peace

talks with the MILF, the MNLF and the CNN,

established a National Unication Commission

and the Oce of the Presidential Adviser on

the Peace Process (OPAPP). It also signed into

law a general conditional amnesty covering all

rebel groups.

24

It was also under Ramos’ term

that Congress repealed the Anti-Subversion Act,

which had previously made mere membership

in the CPP illegal.

25

The Party List System Law

was also enacted, allocating 20 percent of

the seats in the House of Representatives to

representatives of marginalized sectors as

provided in the 1987 Constitution.

26

Moreover,

Ramos championed a 15-year AFP modernization

program that introduced security sector

reforms meant to transform the military

into a professionalized armed force.

18 |

During this period, there was a “dramatic decline

in military encounters between government and

rebel forces and a decline in casualties related to

COIN operations against the NPA, and although

human rights violations were still observed in

militarized zones, there was a notable decline

in most categories.”

27

The Commission on

Human Rights (CHR) cited “improved human

rights awareness in the military, which it attributes

to its human rights training programs for military

ocers and its practice of providing AFP

promotion panels with ‘certicates of clearance’

on ocers’ human rights performance.”

28

While the Ramos period was far from perfect,

it was a fork in the road in reimagining the

relationship between the Philippine state and the

communist armed movement, and in transforming

the Philippine security establishment towards

greater civilian oversight over the military.

This period allowed for “political space within

the state for left-wing activist organizations

sharing the ‘national democratic’ ideology

and programme of reforms of the NDF”

29

,

and for a real chance for a civilian approach

and a peaceful resolution to the armed conflict

through a politically negotiated-settlement.

27 Lamchek, J (2019), p. 62, citing Amnesty International.

28 U.S. Department of State Country Report on Human Rights Practices 1994 - Philippines, published 30 January 1995.

Accessed 17 July 2022.

29 Lamchek, J (2019), p. 61.

In the next section, I will discuss two episodes in

the post-1986 era where COIN took ascendancy

over politically negotiated settlements and

peace processes. The rst was during the

Macapagal-Arroyo administration which

coincided with the Post-9/11 Global War

on Terror (GWoT); the second, the Duterte

administration which coincided with the rise

to global prominence of the Islamic State or

Daesh (IS/ISIL) and consequently, of the P/CVE

(Preventing or Countering Violent Extremism)

agenda. In both the Macapagal-Arroyo and

Duterte administrations, the counterterrorism

state was able to reframe “insurgents” as

“terrorists.” And in both cases, the ultimate

impact was felt most among actors, sectors and

communities whom the Philippine government

and security actors perceived to be ‘mass bases

of support’ of the CPP-NPA. My argument is

counterterrorism (CT) as the discourse was an

intervening opportunity for the military to tilt

the balance in its favor, frustrating healthier

civil-military relations from being fully born

and undermining a new and better relationship

between the Philippine state and the communist

armed movement, and, by extension, with other

dissenting groups.

19 |

C. Macapagal-Arroyo Administration:

The Post-9/11 GWoT and the

Philippines’ ‘War on Terror’

By 2001, under the Macapagal-Arroyo

administration (2001–2010), counterinsurgency

had gained ascendancy. According to Lamchek,

the brief peace negotiations under President

Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo came to a sudden

halt in 2001 “because the ‘war on terror’ made

the COIN campaign that replaced peace

talks materially attractive and normatively

plausible.”

30

Under President Arroyo, the

Philippines became one of the foremost

supporters of the Global War on Terror in

the region,

31

responding to the call for robust

counterterrorism measures through intelligence-

sharing, military and law enforcement

cooperation, and policy and legislation.

Some commentators have noted that the Abu

Sayyaf Group (ASG) was the initial and main

excuse for introducing the “war on terror” to the

Philippines,

32

and as a justication for making

the country the “second front” of this war.

33

The kidnapping by the ASG of guests at the

Dos Palmas resort in Palawan, which killed three

Americans, coupled with allegations that the

ASG was linked to al-Qaeda, provided “the

casus belli for the U.S. military to re-engage

in the Philippines following the September 11,

2001 attacks by al Qaeda.”

34

30 Lamchek, J (2019), p. 88.

31 Operation Enduring Freedom – Philippines (OEF-P) or Operation Freedom Eagle was in place from 2002 to 2015 as part of

Operation Enduring Freedom and the US Global War on Terrorism.

32 Anja Jetschke (2011), ‘Human Rights and State Security: Indonesia and the Philippines’, University of Pennsylvania Press,

p. 233.

33 Walden Bello, ‘A “Second Front” in the Philippines’ The Nation (18 March 2002), p. 18.

34 Abuza, Zachary. ‘Balik-Terrorism: The Return of the Abu Sayyaf,’ Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College

(1 September 2005), vii.

35 Ava Patricia C. Avila & Justin Goldman, ‘Philippine-US relations: the relevance of an evolving alliance,’ Bandung: Journal

of the Global South (29 September 2015), 2, Article No. 6.

36 Renato Cruz De Castro (June 2006), ‘21st Century Philippines-US Security Relations: Managing an Alliance in the War

of the Third Kind’, Asian Security, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 102–121.

37 George Radics, ‘Terrorism in Southeast Asia: Balikatan Exercises in the Philippines and the US “War against Terrorism”’

(2004) 4 Stanford Journal of East Asian Aairs, pp. 115–27, 116–17; Herbert Docena, ‘Unconventional Warfare: Are US

Special Forces Engaged in an “Oensive War” in the Philippines?’ in Abinales and Quimpo (eds) pp. 46–83.

38 Robin A. Bowman, ‘Is the Philippines Proting from The War on Terrorism?’, Monterey, California: Naval Postgraduate

School (June 2004).

As the US identied terrorism as a common

threat, it renewed its political and security

relations with the Philippines, which had been

strained since the closure of the US military

bases in 1991.

35

From 1994 to 1998, the average

amount of US military aid was only US$1.6

million per annum, but in the aftermath of 9/11,

Washington gave Manila a ten-fold increase in

military assistance.

36

Support did not only come

in the form of a nancial military package, it also

included development assistance, especially

to Muslim Mindanao, and the deployment of US

forces for “joint military exercises” with Philippine

troops, including undisclosed numbers of US

Special Operations Forces since 2002.

37

One

commentator noted that “...instead of improving

the country’s CT capabilities to eradicate

terrorism, the GWOT and related US policy have

created a cyclical incentive structure [wherein]

certain actors within the government, military,

and insurgency groups in the Philippines prot

politically and nancially from US aid and the

warlike conditions,” and therefore “sustain, at

a minimum, a presence of conflict and terrorism

in order to continue drawing future benets.”

38

20 |

President Arroyo was interested in a closer

relationship with the security sector, seeking

to “strengthen her relationship with the military,

the institution from which she sought support

to bolster her shaky, increasingly unpopular

administration.”

39

Arugay et al. pointed out

that the increased influence of former military

generals “who had positioned themselves as

the necessary voices with the experience to

handle these security eorts”

40

and who “did

not hesitate to push for a heavily militarized

approach to deal with communist rebels and

Moro secessionists under the counterterrorism

framework” facilitated the civilian government’s

“new ‘all-out war policy’ in dealing with all non-

state armed groups.”

41

At one point, President

Arroyo would say, “The government will not

allow the peace process to stand in the way

of the overriding ght against terrorism.”

42

39 Lamchek, J (2019), p. 86.

40 Aries Arugay, Marc Batac & Jordan Street, ‘An Explosive Cocktail – Counter-terrorism, militarisation and authoritarianism

in the Philippines’, Initiatives for International Dialogue and Safer World (June 2021), p. 9; Arugay, Aries A. ‘The Military in

Philippine Politics: Still Politicized and Increasingly Autonomous, The Political Resurgence of the Military in Southeast Asia:

Conflict and Leadership, edited by Marcus Mietzner’, London: Routledge (2011), pp. 85–106.

41 Arugay A, Batac M & Street J (2021), p. 9; Hutchcroft, David (2008), ‘The Arroyo Imbroglio in the Philippines’,

Journal of Democracy, 19(1), pp 141–155.

42 Quoted in Soliman M. Santos Jr. ‘Counter-terrorism and peace negotiations with Philippine rebel groups’, Critical Studies

on Terrorism (2010), 3:1, pp. 114, DOI: 10.1080/17539151003594301.

43 Santos, S (2010), pp. 137-154.

44 Nathan Gilbert Quimpo. ‘Mindanao: Nationalism, Jihadism and Frustrated Peace’, Journal of Asian Security and

International Aairs (2016), 3(1) p. 7.

45 Anja Jetschke (2011), Human Rights and State Security: Indonesia and the Philippines, University of Pennsylvania Press,

p. 233.

46 Lamchek, J (2018), pp 66-67, citing Anja Jetschke (2011), Human Rights and State Security: Indonesia and the Philippines,

University of Pennsylvania Press.

47 Alfred W McCoy, ‘Policing America’s Empire: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State,’

(Ateneo de Manila University Press 2011), p. 499.

48 Walden Bello, Creating the Third Force: U.S. Sponsored Low Intensity Conflict in the Philippines (The Institute for Food

and Development Policy 1987) 55; Carolina Hernandez, Institutional Response to Armed Conflict: The Armed Forces of

the Philippines (2005) 5–10.

49 Lamchek, J (2019), p. 57.

Commentators argued that the Philippines’

security establishment caught the ‘anti-

terrorism syndrome – i.e., the supremacy of

counter-terrorism’

43

and applied it in their

approach to protracted conflicts with other

insurgent groups like the MILF

44

, and the CPP-

NPA.

45

Jetschke argued that the Philippine

government skillfully used these CT norms

“in constructing a domestic discourse on

terrorism that framed its adversaries as

terrorists or as being linked to terrorism.”

46

However, as McCoy pointed out, the dierence

between the MILF and the CPP-NPA is the

US was already invested in the Philippine

government’s COIN war with the CPP–NPA

long before 9/11, with the CT rhetoric merely

adding “another thread to this skein of historical

continuity.”

47

This is echoed by various

commentators who emphasized the US’ desire

to counter what it saw as a communist threat

to its interests in the Philippines

48

and “the

importance and persistence of Cold War

legacies in explaining the reframing of the

communist movement in terms of terrorism.”

49

21 |

Lamchek succinctly explained:

“[T]errorism was not a stand-alone

phenomenon to which the state responded

with counterterrorism policy; terrorism was

a discursive construction necessitated by

counterterrorism policy and was constituted

as counterterrorism policy was developed…

the Philippine government tried to conjure

an insecure environment abounding in threats,

plots and conspiracies, from the Abu Sayyaf

to the MILF, and on to the NPA and legal leftist

organisations. It was only by taking this specic

view of the security situation as reality, that the

specic counterterrorism measures promoted

made sense. Philippine counterterrorism was

not a necessity. It arose from the contingent

decision of the Arroyo government to align

the country with the ‘war on terror.’ This

aorded the government material and political

advantages against anti-government groups.

By overlaying counterterrorism rhetoric on pre-

existing counterinsurgency, old foes of the state

became terrorists. While espousing the new

terrorism discourse, the government continued

to pursue old counterinsurgency goals with the

increased resources aorded by partnership

with the United States.”

50

50 Lamchek, J (2018), p.89.

51 Ibid, p. 67.

52 UN Human Rights Council, ‘Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions,

Philip Alston : addendum: mission to Philippines,’ (16 April 2008), A/HRC/8/3/Add.2.

53 Peter M Sales, ‘State terror in the Philippines: the Alston Report, human rights and counter-insurgency under the

Arroyo administration. Contemporary Politics, (2009) 15(3), pp 321–336.

The Philippine government “successfully

convinced the United States and other

Western governments to extend its material

and diplomatic support against its adversaries,”

which, “in turn, [made] it possible for human

rights violations to continue.”

51

Unsurprisingly,

with the adoption of the hard security and CT

approach, there was a massive increase in human

rights violations in the form of extrajudicial

killings targeting activists, organizers, journalists

and other civil society actors. Then UN Special

Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or

arbitrary executions Philip Alston estimated that

as many as 800 people were executed between

2002 and 2008.

52

By 2005, this, together with

other authoritarian tendencies prevalent in the

Arroyo administration, led non-government

watchdog Freedom House to downgrade the

Philippines freedom status to “partially free”.

53

[T]errorism was not a stand-

alone phenomenon to which

the state responded with

counterterrorism policy;

terrorism was a discursive

construction necessitated

by counterterrorism policy

and was constituted as

counterterrorism policy

was developed…”

22 |

D. Duterte Administration:

The IS/ISIL Threat, P/CVE Agenda,

and Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020

At the start of the Duterte administration

(2016–2022), the relationship between the

civilian government and the CPP-NPA began

on a positive and promising note, with an

expeditious peace process between the

parties. There was renewed hope among

many that a politically negotiated settlement

that would put an end to the longest-running

armed conflict in Asia, was within reach.

Sections of the military and intelligence

establishment were, of course, displeased

when President Duterte was more than

welcoming of the CPP-NPA and the Left.

During the rst two years of the Duterte

administration, they perceived as unwarranted

concessions, the appointment of Left figures

in the Cabinet and the release of high-value

political prisoners and key time CPP-NPA

leaders Benito Tiamzon and Wilma Tiamzon.

The military only had to wait for the right

opportunity to retake the upper hand.

54 Presidential Proclamation 360, s. November 23, 2017.

55 Rappler, ‘The Duterte administration led a petition seeking to declare the CPP-NPA ‘terrorist’

organisations under the Human Security Act,’ (21 February 2018).

56 Aljazeera, ‘Duterte: Shoot female rebels in their genitals’ (12 February 2018).

57 Aljazeera, ‘Rodrigo Duterte oers ‘per head’ bounty for rebels’ (15 February 2018).

The wedge between the Duterte government

and the CPP-NPA started widening as early

as the rst quarter of 2017. By 23 November

2017, after continued armed encounters

between the AFP and the NPA despite mutual

declarations of unilateral ceaseres, President

Duterte formally terminated the peace talks

with the NDF.

54

The Philippine government

has since escalated its labeling of the CPP-

NPA as a ‘communist terrorist group (CTG)’,

a branding used previously by the military but

not by the Duterte-led civilian government,

until the negotiations were terminated.

55

Duterte no longer held back in his escalatory

remarks inciting increased violence, such as

encouraging soldiers to shoot women rebels in

their vaginas,

56

and oering a bounty for each

communist rebel killed.

57

Within a few months,

the government policy quickly shifted from a

strategy of politically-negotiated settlement

and reforms to a strategy of COIN and CT,

primarily through active warfare, lethal force,

and a punitive approach.

It must be noted that alongside the roller coaster

of the peace process, there were three trends

happening in the global and the national arena

that could explain the shifts in perspective,

dynamics and motivations within the Philippine

government: the threat of the Islamic State or

Daesh (IS/ISIL) and the rise of the Preventing or

Countering Violent Extremism (P/CVE) agenda,

the Marawi Siege of 2017, and the militarization

of the civilian government.

23 |

1. The threat of ISIL/IS and the rise of the

P/CVE agenda

On the global level, IS/ISIL rose to prominence

as it seized large swathes of territory across

Iraq and Syria in 2014, and as a spate of

terror attacks from Paris to Istanbul alarmed

policymakers across the world, counterterrorism

was again catapulted as a top concern for

global policy. Thus emerged a new response to

terror attacks: the P/CVE agenda. P/CVE was

partly a response to the limited success of hard

security “war on terror” tactics.

58

It was designed

to take “proactive actions to counter eorts by

violent ‘extremists’ to radicalize, recruit, and

mobilize followers to violence and to address

specic factors that facilitate violent ‘extremist’

recruitment and radicalization to violence.”

59

58 Abu-Nimer Mohammed, ‘Alternative Approaches to Transforming Violent Extremism. The Case of Islamic Peace, and

Interreligious Peacebuilding’, in B Austin and H J Giessmann (eds.), Transformative Approaches to Violent Extremism.

Berghof Handbook Dialogue Series No. 13 (Berlin: Berghof Foundation, 2018), pp 1–20; Larry Attree, ‘Shouldn’t YOU

be Countering Violent Extremism?’, Saferworld (March 2017).

59 United States Department for Homeland Security, ‘What is CVE?’ Accessed 12 July 2022.

60 US White House Oce of the Press Secretary (2015), ‘Remarks by the President at the Summit on Countering Violent

Extremism February 19, 2015’. Accessed 12 July 2022.

61 United Nations General Assembly, ‘Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism. Report of the Secretary-General’,

A/70/674, (24 December 2015).

62 Arugay, A, Batac, M & Street, J (2021), p. 16.

63 Naz Modirzadeh, ‘If It’s Broke, Don’t Make it Worse: A Critique of the UN Secretary-General’s Plan of Action to Prevent

Violent Extremism’, Lawfare (23 January 2016).

In 2015, the Obama administration held a

“Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) Summit”

to mobilize global support for this approach

60

,

while the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon

issued a UN Plan of Action to Prevent Violent

Extremism.

61

These became the basis for the

roll-out of national action plans around the

world, including in the Philippines, “with UN

agencies playing a central role supporting [and

funding] national governments to produce these

strategies.”

62

For those who rallied behind the

P/CVE agenda, it was promised to be a positive

move away from a security-focused to a more

preventative approach. Critical security scholars

and peacebuilders were not convinced and

warned that similar to the Global War on Terror

post-9/11, the P/CVE agenda could further

enable authoritarian regimes to “subsume

other legitimate interests under the banner

of suppressing ‘violent extremism’.”

63

Source: Photo by Ray Lerma

View of ground zero of Marawi taken on August 21, 2019.

24 |

However, there was growing concern and

posturing that the collapse of the territorial

caliphate of IS/ISIL in Iraq and Syria would push

the group’s activities elsewhere to seek new

territory in Southeast Asia, particularly Indonesia,

Malaysia and the Philippines.

64

This became the

jump-o point for massive capacity-building

assistance, technical support and equipment

to Southeast Asia, and soon P/CVE was the

catchphrase and programming lens across the

region. On the regional level, as early as 2015,

the Association of Southeast Asian Nations

(ASEAN) either adopted or supported various

joint statements signifying a renewed attention

to terrorism and violent extremism, and support

for CVE.

65

In the Philippines, the government,

especially the AFP and the PNP, received support

on CVE and CT from a variety of governments

66

such as the US

67

, Australia

68

and Japan

69

, and even

international organizations such as the UN

70

and

the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism.

71

64 Connor H. Berrier, ‘Southeast Asia: ISIS’s next front’ Monterey, California: Naval Postgraduate School (2017); Nathaniel

L. Moir, ‘ISIL Radicalization, Recruitment, and Social Media Operations in Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines,’ PRISM

Volume 7, No 1 (2017), pp. 91-107.

65 ASEAN member-states adopted or supported the Langkawi Declaration on the Global Movement of the Moderates in April

2015, Kuala Lumpur Declaration in Combating Transnational Crime in September 2015, East Asia Summit Statement on

Countering Violent Extremism in October 2015, Chairman’s Statement of the Special ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on the Rise

of Radicalisation and Violent Extremism in October 2015 and Chairman’s Statement of the 2nd Special AMM on the Rise of

Radicalisation and Violent Extremism. In September 2017, ASEAN Comprehensive Plan of Action on Counter Terrorism and

Manila Declaration to Counter the Rise of Radicalization and Violent Extremism was adopted. In October 2017, Defense

Ministers across the region released a Joint Statement of Special ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting on Countering Violent

Extremism (CVE), Radicalization and Terrorism.

66 Linda Robinson, Patrick B. Johnston & Gillian S. Oak, ‘U.S. Special Operations Forces in the Philippines, 2001–2014,’ Santa

Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation (2016), p. xiv.

67 U.S. Department of State, “Building a Global Movement to Address Violent Extremism,” fact sheet, September 2015.

Accessed 12 July 2022.

68 Strait Times, “Australia Backs Philippine Campaign Against Terrorism,” (19 March 2018).

69 U.S. Department of State (2015).

70 Arugay A, Batac M & Street J (2021), p. 16.

71 U.S. Department of State (2018).

72 GMA News Online, ‘AFP Adopts New Security Plan Under Duterte’ (6 January 2017).

73 Ashley L. Rhoades & Todd C. Helmus, ‘Countering Violent Extremism in the Philippines: A Snapshot of Current Challenges

and Responses.’ Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2020.

74 Japan Times. ‘Philippines adopts strategy against violent extremism’ (21 July 2019).

75 Aljazeera, ‘Mindanao: Churchgoers ‘taken hostage’ amid Marawi siege,’ (24 May 2017).

76 New York Times, ‘Duterte Says Martial Law in Southern Philippines Will End This Month,’ (December 10, 2019);

Al Jazeera, ‘Philippines’ Duterte to Lift Martial Law by Year’s End,’ (10 December 2020).

77 Georgi Engelbrecht, ‘Resilient Militancy in the Southern Philippines,’ International Crisis Group (17 September 2020).

78 The UN High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that 98% of residents were displaced at the height of the siege.

‘International Agency Update,’ UNHCR (October 2017).

As announced in January 2017, the AFP’s top

priority was the eradication of any terrorist group

operating within the Philippines.

72

Simultaneously,

the Philippine government endeavored to increase

the role and improve the capabilities of the PNP

in CT and CVE eorts.

73

The Philippines began

developing its National Action Plan on P/CVE

(NAP P/CVE) in July 2017 and adopted it in mid-

2019

74

, making it the rst country in Asia to do so.

2. The Marawi Siege

The second parallel event was the rise of terror-

related violence in Mindanao. On 23 May 2017, the

city of Marawi, the country’s only Muslim-majority

city, was the scene of the most prominent CT

campaign in the country’s history when the AFP

raided a suspected hideout of the Abu Sayyaf Group

leader Isnilon Hapilon in Marawi City. In response,

Hapilon sought reinforcements from members of the

armed Maute Group that had pledged allegiance

to the ISIL, leading to sporadic reghts with the

military in various parts of the city.

75

Later that day,

President Duterte declared Martial Law throughout

Mindanao, and did not lift it until 31 December

2019.

76

The military proceeded to air bomb the city

to flush out the rebels. The battle for Marawi lasted

ve months until the city was declared liberated

in October 2017.

77

Six years after its destruction,

many Marawi residents remain displaced.

78

25 |

The Marawi Siege was used as justication for

taking a tougher stance against violent groups,

or for bringing terrorism back as a primary

security agenda. It also contributed to the belief

that the Philippines is the second frontier of IS/

ISIL’s global jihad and provided an opportunity

for the government to step on the gas of CT

in the country. Coincidentally, the process of

developing the NAP P/CVE began at around

the time of the Marawi siege.

79

3. Militarization of the Civilian Government

At the start of his administration, President

Duterte was dead set on wooing the military,

immediately doing the rounds of 14 military

camps in less than a month, promising to

strengthen the armed forces and increase

the soldiers’ salaries and benets.

80

Although there were issues where the President

and sections of the security sector did not see

eye-to-eye, like the initial peace talks with the

CPP-NPA and his non-confrontational stance on

the maritime conflict with China, Duterte knew he

had to secure the support of the armed forces to

ensure the stability and survival of his government.

81

At one point, he expressed his fear of a military

coup

82

, which could explain the change in his

stance on the CPP-NPA. As fractures appeared

in the initial relationship between Duterte and the

Left, ex-generals were appointed to top cabinet

posts replacing Left-leaning ocials.

83

79 Arugay A, Batac M & Street J, (2021), p. 16.

80 Rappler, ‘Why has Duterte visited 14 military camps in less than a month?’ (20 August 2016).

81 GMA News, ‘Duterte and the Left: A BROKEN RELATIONSHIP,’ (27 December 2020).

82 Aljazeera, ‘‘Kill them’: Duterte wants to ‘nish o’ communist rebels,’ (6 March 2021).

83 GMA News, ‘Duterte and the Left: A BROKEN RELATIONSHIP,’ (27 December 2020).

84 Aries Arugay, ‘The Generals’ Gambit: The Military and Democratic Erosion in Duterte’s Philippines,’ Heinrich Böll Stiftung

Southeast Asia (18 February 2021).

85 DBM, ‘President Duterte fullls campaign promise, doubles salaries of cops, soldiers,’ created 10 January 2018, last

updated 11 January 2018.

86 PNA, ‘Strong support for AFP, one of Duterte’s legacies,’ (19 July 2021).

87 Inquirer, ‘Duterte hires 59 former AFP, PNP men to Cabinet, agencies’ (27 June 2021).

88 ABS-CBN News, ‘Duterte’s Generals: Revolving doors and how they lead military men back to government,’ (5 February 2021).

89 The General in-charge of the Marawi Siege was appointed its Secretary when he retired.

90 Rappler, ‘Duterte to appoint AFP chief Galvez as OPAPP chief,’ (5 December 2018).

91 Sunstar, ‘Militarization? Correct, says Duterte’ (1 November 2018).

Arugay argues that “no president in the country’s

post-martial law history has favored the military

[more] than Duterte.”

84

In 2018, realizing his earlier

promise, President Duterte doubled the salaries

of military and police ocers.

85

By the end of

the Duterte administration, new equipment and

facilities under the AFP Modernization Program

(that was started by previous administrations

but delivered under Duterte) amounted to around

PhP125 billion in appropriated funds.

86

By 2017,

Duterte had the most number of retired generals in

any presidential Cabinet in the post-dictatorship

period, with 59 former military and police generals

leading various civilian agencies.

87

He appointed

generals to head department portfolios that

deal not only with national defense but also

civilian concerns

88

such as interior and local

government, information and communications,

the environment, social welfare and development,

89

housing, and indigenous people’s (IP) concerns.

He even appointed an outgoing AFP Chief of

Sta to lead the agency in charge of the peace

processes,

90

signaling his dependence on the

military to accomplish the country’s peace

and security goals. By 2017, the military and

intelligence actors had gained the upper hand in

the Cabinet and had the ears of President Duterte.

In October 2018, he defended the appointment of

former military ocers in civilian positions saying

that they are more ecient and always follow

his orders, even admitting to the “militarization”

of the government.

91

26 |

This dependence on former-military generals and

the armed forces created an imbalance in civil-

military relations, enabling the shift to securitized

military-rst policies and violence on a number