Counted Out: Black, Asian and minority

ethnic women in the criminal justice system

About the Prison Reform Trust

The Prison Reform Trust is an independent UK charity working to create a just, humane and effective prison

system. We have a longstanding interest in improving criminal justice outcomes for women and our strategy

to reduce the unnecessary imprisonment of women in the UK is supported by the Big Lottery Fund.

The Transforming Lives programme: reducing women’s imprisonment

About 13,000 women are sent to prison in the UK every year, twice as many as twenty years ago,

many on remand or to serve short sentences for non-violent offences, often for a first offence.

Thousands of children are separated from their mothers by imprisonment every year. Yet most of the solutions

to women’s offending lie in the community. The Prison Reform Trust is working with other national and local

organisations to promote more effective responses to women in contact with the criminal justice system. It is

a specific objective of the Transforming Lives programme to reduce the numbers of Black,

Asian and minority ethnic women and foreign national women in prison. For further information see

www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/women

About this briefing

In this briefing we highlight the different experiences of women from minority ethnic groups in the criminal

justice system in England and Wales, mainly in comparison to white British women but also in relation to men

who are white British and men who are from minority ethnic groups. We also consider the experience and

needs of Muslim women who may be subject to particular cultural pressures and prejudices. We propose

measures to help ensure that women are not disadvantaged in their contact with criminal justice agencies

because they are Black, Gypsy, Roma or Traveller, Asian, Muslim or from any other minority ethnic or religious

group.

A note on terminology

In this report we have used the classifications of ethnicity adopted by the review by David Lammy MP of

possible racial bias in the criminal justice system (the Lammy review) which in turn reflect the ethnic group

classifications used by the Office for National Statistics. However we have in general chosen not to use the

acronym ‘BAME’, which is widely used to mean ‘Black, Asian and other minority ethnic’. Instead we have

used this term in full, or used the term ‘women from minority ethnic groups’, with the same intended meaning.

Both terms are intended to include white women who belong to minority ethnic groups.

In the context of official statistics, references to Black women tend to mean women of African or Caribbean

descent. In the same context, references to Asian women tend to mean women from South Asia, whereas

references to Chinese and ‘other ethnic’ women tend to refer to women from South East Asia, the Middle East

and North Africa. Further notes on terminology appear in the relevant sections of this report.

Where we use the term ‘community’ we are referring to women’s ethno-cultural or religious communities or

backgrounds, depending on the context.

Credits and acknowledgements

This briefing would not have been possible without the support of the Big Lottery Fund.

The briefing was researched by Eliza Cardale and written in consultation with Dr Kimmett Edgar,

Katy Swaine Williams and Jenny Earle of the Prison Reform Trust (PRT), with additional assistance from

Zoey Litchfield of the PRT and PRT volunteer Lauren Nickolls.

We are grateful to those who have reviewed and contributed to drafts of this report, including Sofia Buncy

of Muslim Women in Prison, a project of the Huddersfield Pakistani Community Alliance in partnership with

Khidmat Centres; Adrienne Darragh of Hibiscus Initiatives; Marai Larasi MBE of Imkaan; and Dale Simon CBE,

Advocate Consultant to the Young review.

© Prison Reform Trust, 2017

Cover image: Warrior to the Rescue, HM Prison & Young Offender Institution Holloway (women’s

establishment), Commended Award for Printmaking 2016. Image courtesy of the Koestler Trust.

ISBN: 978-1-908504-27-2

1

Counted Out

Counted Out: Black, Asian and minority

ethnic women in the criminal justice system

Foreword 2

Introduction 3

Executive summary 5

Summary of Findings 5

Recommendations 7

Methodology 9

Key facts on minority ethnic women in the criminal justice system 10

What does the evidence show? 13

The evidence in more detail 17

Girls from minority ethnic groups 17

Black women 17

Asian women 20

Women of Muslim faith 22

‘Mixed ethnic’ women 23

Chinese and ‘other ethnic’ women 24

Gypsy, Roma and Traveller women 25

Experiences of custody 27

Safety in custody 28

Experiences post-release 30

Minority ethnic women in the criminal justice workforce? 30

Conclusions 32

Note on statistical sources 33

Bibliography 33

Useful organisations 35

2

Counted Out

Foreword

This report makes difficult but necessary reading. Sadly, the issues that Prison Reform Trust

highlights here are not new or even surprising. We know that deeply held negative ideas around

Black and ‘minority ethnic’ people make their way into how women and girls are treated across

our society. We also know that women and girls routinely face multiple, intersecting inequalities

and that the criminal justice system is too often the ‘hard face’ of this injustice.

While the statistics quoted in the report are important, it is more important for us to remember the

individual women and girls who are at the heart of that data. Each of their lives is important and

valuable, and not only as mothers, carers, partners and daughters, but as women and girls in their

own right. Each experience of harsh sentencing or poor treatment in prison will have caused harm

to that woman or girl. Each woman or girl who has had her experiences of abuse ignored, and

who has been viewed only through a lens of criminality rather than vulnerability has been failed by

the system. Each Black or ‘minority ethnic’ woman or girl who has been rendered hyper-visible or

invisible within the criminal justice system is a woman who has been failed by our society.

I welcome the recommendations made in this report. The current situation should not be viewed

as inevitable or acceptable. We need commitment to improvement, and we need sustained action

which leads to a step-change in justice and equality. I urge policy makers, commissioners and

others to take these recommendations forward with a view to ensuring that the lives of Black and

‘minority ethnic’ women and girls really count.

Marai Larasi MBE

Executive Director, Imkaan

3

Counted Out

Introduction

The disadvantages all women face with the criminal justice system, such as experiencing a

greater likelihood of imprisonment than men for first offences and non-violent offences, higher

rates of remand and poorer outcomes on release

1

, are compounded for Black, Asian and minority

ethnic women. They make up 11.9% of the women’s population in England and Wales, but 18%

of the women’s prison population.

2

This represents a decline since 2012 when it was 22%, but it

remains significantly disproportionate.

3

Women from minority ethnic groups face many of the same challenges as white British women

compared to men within the criminal justice system, including exposure to domestic and/or

sexual abuse, problematic substance use, and the probability that they have the primary care

of dependent children. There is surprisingly little published information about the ethnicity of

women in the criminal justice system. For example, we know the ethnic origin of those in prison

on any given date (the ‘snapshot’ figure) but not that of women received into prison over the

course of a year (the reception figure). Nor is information published on the ethnicity of women

who are recalled back to prison following release, or of women who are on community orders.

However, even the currently limited range of published statistics and survey evidence lays bare

real disparities:

• Black women are more likely than other women to be remanded or sentenced to

custody.

• Black women are more likely to be sole parents so their imprisonment has

particular implications for children.

• Women from minority ethnic groups are more likely to plead not guilty in the

Crown Court, leaving them open to potentially harsher sentencing.

• Women from minority ethnic groups feel less safe in custody and have less access

to mental health support, according to surveys by HM Inspectorate of Prisons

(HMIP).

• Women from minority ethnic groups experience racial and religious discrimination

in prison from other prisoners and from staff, according to surveys by HMIP.

• Some women from minority ethnic groups are also foreign nationals and may be

subject to immigration control and face language and cultural barriers.

• Asian and Muslim women may experience particularly acute stigma from their own

communities.

• There are very few specialist organisations working with women from minority

ethnic groups in the criminal justice system

1. Prison Reform Trust (2017) Why focus on reducing women’s imprisonment? London: PRT.

2. Table DC2101EW, Office for National Statistics (2012) 2011 Census, London: ONS; Table 1.4, Ministry of Justice (2016) Population bulletin: weekly 31 March 2017, London:

Ministry of Justice

3. Table A1.7, Ministry of Justice (2013) Prison population tables, London: Ministry of Justice

4

Counted Out

While the experiences of women from minority ethnic groups are individual and diverse, the

extent to which they have been neglected or misunderstood is something they have in common.

The 2007 Corston Review of the needs of vulnerable women in prison, stated that women from

minority ethnic groups are ‘further disadvantaged by racial discrimination, stigma, isolation,

cultural differences, language barriers and lack of employment skills’.

4

This remains true a decade

on.

This briefing is intended to help remedy past neglect and inspire the development of a more

informed approach that will ensure and monitor equitable outcomes for women from minority

ethnic groups, and foster the specialist organisations that work with them.

4. Corston, J. (2007) The Corston Report. London: Home Office

5

Counted Out

Executive Summary

Summary of Findings

Lack of data and research signifies neglect and impedes progress

• There is limited criminal justice data disaggregated by both gender and ethnicity

which makes it harder to identify accurately and address effectively the disparities

experienced by women from minority ethnic groups in the criminal justice system.

• There has been little qualitative or quantitative research into the experiences of

women from minority ethnic groups in the criminal justice system, particularly

outcomes after release from custody or receipt of non-custodial sentences.

• There is minimal data disaggregated by gender and religion, constraining analysis

of the experiences of Muslim women, whose numbers in prison are growing.

• There is minimal data on Gypsy, Roma and Traveller women, and little known

about their experiences, despite considerable over-representation in custody.

Available evidence confirms that women from minority ethnic groups are

disadvantaged compared to white women in the criminal justice system

• There is disproportionate use of custodial remand and custodial sentencing for

Black women.

• Women from minority ethnic groups are more likely to plead not guilty at the

Crown Court, impacting on their sentences if convicted.

• As Black women are more likely to be lone parents, custodial sentences may have

a particularly significant impact on their families.

• Women from minority ethnic groups feel less safe in custody and have less access

to mental health support.

• Women from minority ethnic groups experience racial and religious discrimination

in prison from other prisoners and from staff.

• Some minority ethnic women are also foreign nationals and therefore subject

to additional difficulties, including language barriers and extended detention

associated with being subject to immigration control.

• Asian and Muslim women may experience particularly acute stigma from their own

communities as a result of their involvement with the criminal justice system.

• There is no available data on the number of Black, Asian or minority ethnic women

sitting as magistrates or judges or employed in the probation, prison or police

services.

• While there has been a significant reduction in the numbers of young people

entering the criminal justice system and going into custody since 2008, these

benefits have not been felt equally across ethnicities.

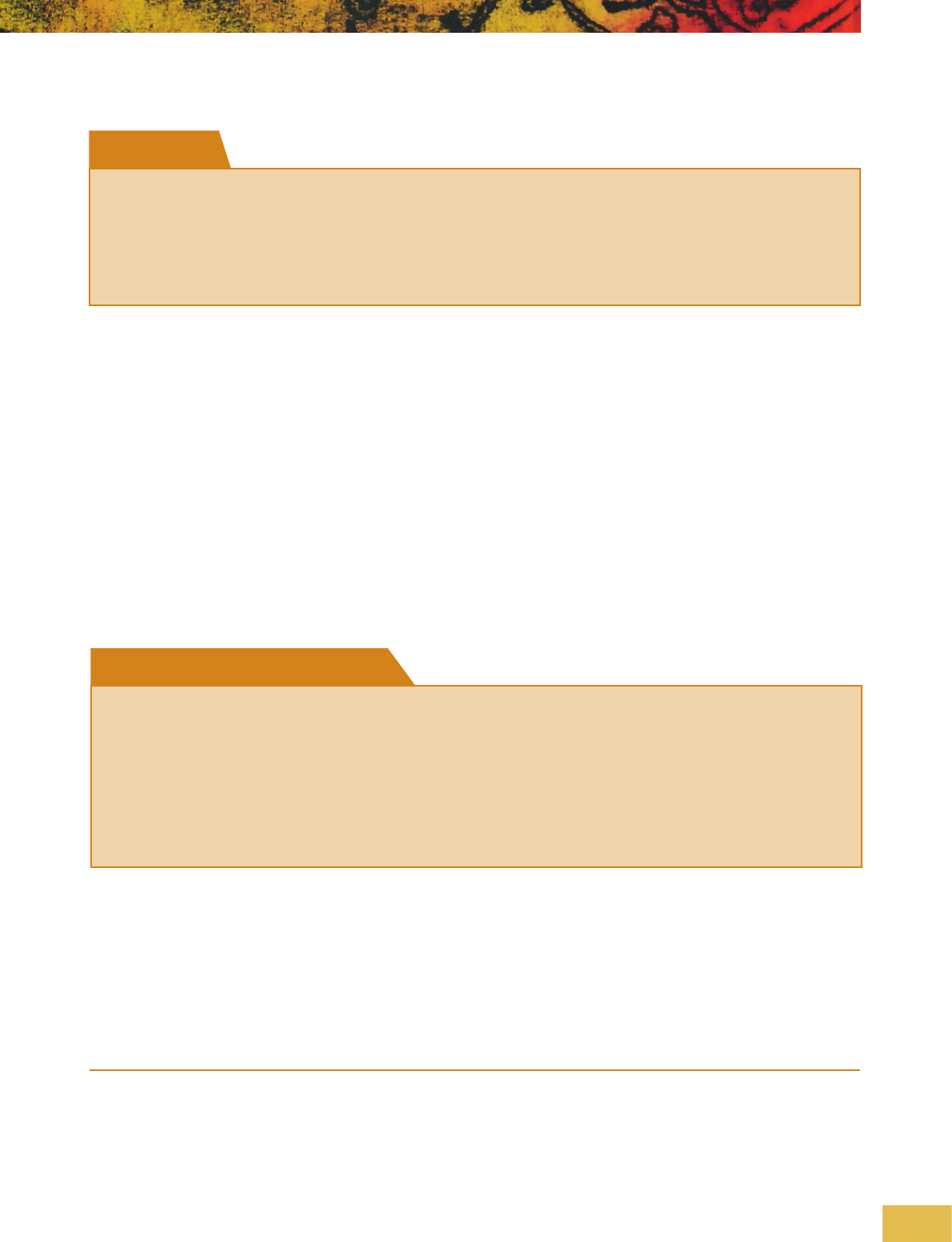

1

2

Counted Out

6

Summary of Findings

3

There are very few specialist, local services working with women offenders

from minority ethnic groups

• Women report being more likely to access support, and feeling safer to speak

about their experiences, within services led by and for women from minority ethnic

groups.

• There are few organisations either working exclusively with or running

programmes for Black, Asian or minority ethnic women offenders.

• Government budget cuts have reduced the availability of specialist support

services for Black, Asian and minority ethnic women affected by domestic abuse

and other forms of violence against women and girls.

5

Bangkok Rules

The United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Female Prisoners and Non-Custodial Measures

for Women Offenders (known as the Bangkok Rules, 2010) to which the UK is a signatory, make

specific provisions for ethnic minority women in prison:

Rule 54: Prison authorities shall recognize that women prisoners from different religious and

cultural backgrounds have distinctive needs and may face multiple forms of discrimination in

their access to gender- and culture-relevant programmes and services. Accordingly, prison

authorities shall provide comprehensive programmes and services that address these needs, in

consultation with women prisoners themselves and the relevant groups.

Rule 55: Pre- and post-release services shall be reviewed to ensure that they are appropriate

and accessible to indigenous women prisoners and to women prisoners from ethnic and racial

groups, in consultation with the relevant groups.

6

5 Imkaan (2016) Capital Losses: The state of the BME ending violence against women and girls sector in London. London: Imkaan

6 UN General Assembly (2010) UN Resolution 65/229 United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders (the

Bangkok Rules). UN General Assembly: New York

3

Counted Out

7

Recommendations

The forthcoming government strategy on female offenders, to be published by

the Ministry of Justice later in 2017, should include specific measures to improve

outcomes for Black, Asian and minority ethnic women and women from minority

faith communities in contact with the criminal justice system. Proposed measures

should reflect:

• consultation with women who have direct experience of the criminal justice

system and specialist services in the community that work with them;

• a rebalancing of investment away from the custodial estate and towards

community solutions.

Criminal justice agencies should collect and publish data disaggregated by

gender, ethnicity (including Gypsy, Roma and Traveller backgrounds) and religion

to inform policy and practice and ensure compliance with the public sector

equality duties. This data should:

• include all sentencing disposals, prison receptions, remands, releases and recalls;

• inform local authority joint strategic needs assessments and commissioning

decisions;

• be appropriately shared by the police, courts, Community Rehabilitation

Companies (CRCs) and National Probation Service (NPS) and scrutinised for

evidence of disproportionality or unmet need;

• be used to monitor progress in addressing unequal outcomes.

The criminal justice inspectorates should conduct a joint thematic review to

investigate the extent and nature of disparities in experience of women from

minority ethnic groups and make detailed recommendations to all responsible

agencies for how these can be addressed. This could for example include a

National Statement of Expectations for working with women from minority

ethnic groups.

Key guidance documents, such as the Equal Treatment Bench Book and NOMS

Guide to working with women offenders, should be updated to address specific

considerations for women from minority ethnic groups and Muslim women.

1

2

3

4

8

Counted Out

5

6

7

8

9

Steps should be taken to ensure appropriate ethnic diversity of jury members, and

to tackle unconscious gender and racial bias.

A strategy to increase minority ethnic women’s representation in the criminal

justice workforce should be adopted by the Ministry of Justice, HM Prisons and

Probation Service (HMPPS) and the Home Office. All criminal justice agencies

should take steps to improve the recruitment and retention of minority ethnic

women and ensure transparent data recording so that progress can be measured.

This should include police, courts, probation and prison service staff, as well as the

magistracy and the judiciary. Culturally-informed and gender-responsive training

should be provided throughout the criminal justice workforce. This should include

programmes enabling staff and officers to understand and challenge their own

unconscious biases.

The Judicial College should provide information and training to the judiciary on

the different experiences and needs of women from minority ethnic groups as part

of the social context within which they operate. This should include programmes

enabling members of the judiciary to understand and challenge their own

unconscious biases.

The National Probation Service should ensure that pre-sentence reports,

whether oral or written, draw the court’s attention to relevant cultural factors and

pressures, and training for offender managers should include cultural awareness

relevant to their client groups. This may include for example family dynamics and

gender-power relations in a woman’s community, the impact of sentencing on

dependent children

7

, and programmes enabling offender managers to understand

and challenge their own unconscious biases.

National and local government should work together to ensure the provision

of services to support women from minority ethnic groups in the community.

The focus should be on increasing and strengthening specialist services and

ensuring safe spaces are available for women from minority ethnic groups.

Local commissioners must evidence consultation and partnership working with

specialist organisations, and be held to account for this.

7 For a summary of law and practice see Prison Reform Trust (2015) Sentencing of Mothers, London: PRT

9

Counted Out

Methodology

In preparing this briefing we have drawn upon government statistics and the interim

report published in November 2016 by the Lammy review,

8

which identified pronounced

disproportionality in the treatment of women from minority ethnic groups at the point of arrest, in

relation to custodial remand and sentencing, and in prison discipline adjudications.

9

We have also drawn upon the research commissioned by the Lammy review from Agenda and

Women in Prison, published in April 2017, which gave voice to women from minority ethnic

groups through focus group discussions.

10

We conducted our own analysis of information from recent HM Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP)

reports from women’s prisons. The prisoner surveys in seven reports published since February

2014 were analysed to compare the responses of women from minority ethnic groups to those

of white women.

11

We also conducted a focus group with foreign national women, hosted by

Hibiscus Initiatives at their London specialist women’s centre.

It is difficult to draw specific conclusions about racial disparities in criminal justice outcomes

given the numerous and complex drivers to offending, including socio-economic inequalities,

and the many factors that can affect decisions on prosecution, remand and sentencing. Care is

needed in interpreting statistics when the numbers involved are relatively small. In developing our

analysis and recommendations we have consulted individuals and organisations with specialist

expertise and experience and these are listed above under Credits and Acknowledgements.

8 David Lammy MP was commissioned by the UK government in January 2016 to consider the treatment of, and outcomes for, black, Asian and minority ethnic adults and

young people within the criminal justice system in England and Wales (the Lammy review).

9 Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

10 Cox, J. and Sacks-Jones, K. (2016) Double Disadvantage: The experiences of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic women in the criminal justice system, London: Agenda and

Women in Prison

11 HMP Eastwood Park (November 2016), HMP East Sutton Park (August 2016), HMP Drake Hall (July 2016), HMP Foston Hall (June 2016), HMP Bronzefield (November 2015),

HMP Peterborough (July 2014), HMP Send (February 2014)

Key facts on minority ethnic women in the criminal

justice system

12

Black women

Black women make up 3% of the total female population in England and Wales, but 6.7% of

women entering the criminal justice system for the first time

13

and 8.9% of the women’s snapshot

prison population.

14

There are marked local and regional variations. For example in London, 9.8% of women are

Black,

15

yet Black women made up 20.7% of first time entrants into the criminal justice system.

16

In West Yorkshire, where 1.8% of the general population of women are Black, at least 3.7% of first

time entrants are Black - but ethnicity is unrecorded for 31% of women first time entrants in West

Yorkshire.

17

Black women are

18

29% more likely than white women to be remanded in custody at the Crown

Court.

Following a conviction, Black women are 25% more likely than white women to receive a

custodial sentence.

Asian women

Asian women are generally under represented within the criminal justice system. However in the

West Midlands, where Asian women represent 7.5% of the women’s population, they comprise

12.2% of first time entrants to the criminal justice system.

19

Forty per cent of Asian women receiving convictions in 2015 had no previous convictions,

compared with 12% of white women. Only 15% of Asian women had more than ten previous

convictions, compared with 43% of white women.

20

Asian women and girls are less likely to be arrested than white women and girls across almost all

offence types. The exception is for fraud offences, where Asian women are 26% more likely to be

arrested than white women. Asian women are 51% more likely than white women to plead not

guilty at Crown Court,

21

the highest rate of any ethnic group. This may lead to longer sentences,

where women are convicted.Once in custody, Asian women face additional stigma from their

community, for themselves and their families.

22

12. For a comprehensive briefing on women in the criminal justice system see PRT 2017 Why focus on reducing women’s imprisonment

13. Ministry of Justice (2017) Offending history data tool: First time entrants, December 2016, London: Ministry of Justice

14. Table DC2101EW, Office for National Statistics (2012) 2011 Census, London: ONS; Table 1.4, Ministry of Justice (2016) Population bulletin: weekly 31 March 2017, London:

Ministry of Justice

15 EE1: Estimated resident population by ethnic group and sex, mid-2009 (experimental statistics) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2011/may/18/

ethnic-population-england-wales accessed 13/06/17 (this data includes women aged 16 years and over)

16 Op Cit Ministry of Justice (2017)

17 EE1: Estimated resident population by ethnic group and sex, mid-2009 (experimental statistics) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2011/may/18/

ethnic-population-england-wales accessed 13/06/17 (this data includes women aged 16 years and over); Ministry of Justice (2017) Offending history data tool: First time

entrants, December 2016, London: Ministry of Justice

18 Table 5.3, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

19 EE1: Estimated resident population by ethnic group and sex, mid-2009 (experimental statistics) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2011/may/18/

ethnic-population-england-wales accessed 13/06/17; Ministry of Justice (2017) Offending history data tool: First time entrants, 18 May 2017, London: Ministry of Justice

20 Ministry of Justice (2016) Offending history data tool, September 2016, London: Ministry of Justice

21 Table 5.3, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

22 Buncy, S. and Ahmed, I. (2014) Muslim Women in Prison. Second Chance Fresh Horizons: A study into the needs and experiences of Muslim women at HMP & YOI New Hall

& Askham Grange prisons during custody and post-release, Bradford: HPCA and Khidmat Centres: https://muslimhands.org.uk/_ui/uploads/kqe5a9/MWIP_Report.pdf

3%

6.7%

8.9%

Of the total

female

population in

England and

Wales

Black women make up:

Of women

entering the

criminal justice

system for the

first time

13

Of the women’s

snapshot

prison

population

14

Black women

There are marked local and regional variations.

For example in London, 9.8% of women are

Black,

15

yet Black women made up 20.7% of first

time entrants into the criminal justice system.

16

In West Yorkshire, where 1.8% of the general

population of women are Black, at least 3.7%

of first time entrants are Black - but ethnicity is

unrecorded for 31% of women first time entrants

in West Yorkshire.

17

Black women

18

29%

Following a conviction, Black women are

more likely than white women to

be remanded in custody at the

Crown Court .

more likely than white women to

receive a custodial sentence.

25%

Asian women are generally under represented

within the criminal justice system. However in the

West Midlands, where Asian women represent

7.5% of the women’s population, they comprise

12.2% of first time entrants to the criminal justice

system.

19

Forty per cent of Asian women receiving

convictions in 2015 had no previous convictions,

compared with 12% of white women. Only 15%

of Asian women had more than ten previous

convictions, compared with 43% of white

women.

20

Asian women and girls are less likely to be

arrested than white women and girls across

almost all offence types. The exception is for

fraud offences, where Asian women are:

more likely to be arrested than white

women.

Asian women are

more likely than white women

to plead not guilty at Crown Court,

21

the highest rate of any ethnic group. This may

lead to longer sentences, where women are

convicted.

Once in custody, Asian women face additional

stigma from their community, for themselves and

their families.

22

Asian women

26%

51%

10

Counted Out

Women of Muslim faith

The proportion of Muslim women in custody has increased from 5.2% to 6.3% since March 2014

– up from 203 Muslim women to 251 on 31 March 2017.

23

The Muslim Women in Prison project has reported on the disadvantages faced by Muslim women

in prison without English language skills, particularly older women, who have had to rely on other

prisoners to interpret for them. As this is not a formal arrangement, there is no guarantee of

continuity: interpreters may be released, or transferred without warning.

24

Chinese and ‘other ethnic’ women

Women within the ‘Chinese and other ethnic’ group are 89% more likely to be arrested than white

women, and 32% less likely than white women to be proceeded against.

25

Gypsy, Roma and Traveller women

Prison records indicate about 0.3% of women in custody are Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (GRT)

women,

26

but HMIP survey responses record much higher numbers. In particular, 9% of women

at HMP Foston Hall, 9% at HMP Bronzefield, and 10% at HMP Peterborough, identified as GRT.

These numbers are very high in comparison to official estimates of Gypsies and Travellers in

the general population (0.1%) and even the estimates by GRT organisations (0.5%).

27

Across all

prisons, women have been more likely than men to identify themselves as GRT (7% compared

with 5%). The HMIP report on Gypsies, Romany and Travellers also found that this group were

more likely to feel victimised, more likely to be experiencing mental health problems and less likely

to feel safe in custody.

28

23 Table 1.5, Ministry of Justice (2017) Prison population: 31 March 2017, London: Ministry of Justice

24 Buncy, S. and Ahmed, I. (2014) Muslim Women in Prison. Op Cit.

25 Table 5.1, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

26 HMP Eastwood Park (November 2016), HMP East Sutton Park (August 2016), HMP Drake Hall (July 2016), HMP Foston Hall (June 2016), HMP Bronzefield (November 2015),

HMP Peterborough (July 2014), HMP Send (February 2014)

27 Gypsy and Traveller population in England and the 2011 Census, London: ITMB; Office for National Statistics (2013) Annual Mid-year Population Estimates, 2011 and 2012,

London: ONS

28 HMIP (2014) People in prison: Gypsies, Romany and Travellers: A findings paper by HM Inspectorate of Prisons. London: HMIP

Gypsy, Roma and Traveller

women

Women of Muslim faith

The Muslim Women in Prison project has

reported on the disadvantages faced by Muslim

women in prison without English language

skills, particularly older women, who have had

to rely on other prisoners to interpret for them.

As this is not a formal arrangement, there is no

guarantee of continuity: interpreters may be

released, or transferred without warning.

24

The proportion of Muslim women in custody

has increased from:

since March 2014 – up from 203 Muslim

women to 251 on 31 March 2017.

23

5.2% to 6.3%

89%

Women within the ‘Chinese and other ethnic’

group are:

more likely to be

arrested than white

women.

Chinese and ‘other ethnic’

women

32%

less likely than

white women to be

proceeded against

25

9% 9%

10%

Prison records indicate about 0.3% of women

in custody are Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (GRT)

women,

26

but HMIP survey responses record

much higher numbers. In particular:

These numbers are very high in comparison

to official estimates of Gypsies and Travellers

in the general population (0.1%) and even the

estimates by GRT organisations (0.5%).

Across all prisons, women have been more

likely than men to identify themselves as GRT

(7% compared with 5%).

27

The HMIP report on

Gypsies, Romany and Travellers also found that

this group were more likely to feel victimised,

more likely to be experiencing mental health

problems and less likely to feel safe in custody.

28

of women at

HMP Foston

Hall

of women

at at HMP

Bronzefield

of women

at at HMP

Peterborough

11

Counted Out

12

Counted Out

Migrant women and trafficked women

29

A significant proportion of foreign national women in prison have been trafficked or coerced into

offending.

30

This is also increasingly likely to be the case for British women and girls.

31

Women from minority ethnic groups were more likely at five out of the seven prisons recently

inspected to identify as foreign national.

32

At HMP Send, they were also less likely to understand

written English than white women.

33

Hibiscus Initiatives have identified a growth in the numbers of

people in the criminal justice system for whom English is not their first language, and report that

women and girls tend to have higher needs in this area as a result of more restricted access to

education. This also has an impact on women’s ability to understand decisions made in relation to

criminal cases and immigration status.

34

Girls from minority ethnic groups

While there has been a sustained and significant reduction in the numbers of young people going

into custody since 2008, as well as a drop in young people entering the criminal justice system,

these benefits have not been felt equally across ethnicities. There has been an 84.9% drop over

ten years since 2006 in the number of white girls receiving convictions. For black girls, there has

been a smaller (73.5%) reduction in convictions over the same period.

Safety in custody

Prison inspection reports highlight concerns about safety and access to support for women from

minority ethnic groups, who are more likely to say they have been victimised by other prisoners

because of their ethnicity, at all prisons except HMP East Sutton Park, where none of the

respondents said they had been so victimised.

35

Recorded rates of self-harm are higher among white women in prison, representing over 90% of

incidents over the last ten years.

36

Women from minority ethnic groups may be under-represented

in these statistics, for reasons including under-reporting, or misreading of the range of emotional

responses that women may have to trauma. However, there has been an increase in the recorded

rates of self-harm amongst women from minority ethnic groups, in particular amongst mixed

ethnic women.

Women from minority ethnic groups in the criminal justice workforce

Regrettably there is no official data available on the number of women from minority ethnic groups

working in the criminal justice system.

29 See Prison Reform Trust (2012) No Way Out, London: PRT and an update of that publication to be published by PRT with Hibiscus Initiatives in late 2017.

30 Hales, L. & Gelsthorpe, L. (2012) The criminalization of migrant women Cambridge: Institute of Criminology

31 NCA (2017) National Referral Mechanism Statistics – End of Year Summary 2016, London: NCA. This reported a 100.8% increase from 2015 to 2016 in the numbers of girls

being referred to the NRM due to suspected trafficking within the UK. For adult women there was a 10.9% increase. The UK was the most common country of origin for girls

referred to the NRM in 2016.

32 HMP Eastwood Park (November 2016), HMP Foston Hall (June 2016), HMP Bronzefield (November 2015), HMP Peterborough (July 2014), HMP Send (February 2014)

33 HMP Send (February 2014)

34 Hibiscus Initiatives (2014) The Language Barrier to Rehabilitation. London: Hibiscus Initiatives

35 HMP Eastwood Park (November 2016), HMP East Sutton Park (August 2016), HMP Drake Hall (July 2016), HMP Foston Hall (June 2016), HMP Bronzefield (November 2015),

HMP Peterborough (July 2014), HMP Send (February 2014)

36 Table 2.7, Ministry of Justice (2016) Self-harm in prison custody 2004 to 2015, London: Ministry of Justice

Safety in custodyMigrant women and trafficked

women

29

A significant proportion of foreign national

women in prison have been trafficked

or coerced into offending.

30

This is also

increasingly likely to be the case for British

women and girls.

31

Women from minority ethnic groups were

more likely at five out of the seven prisons

recently inspected to identify as foreign

national.

32

At HMP Send, they were also less

likely to understand written English than white

women.

33

Hibiscus Initiatives have identified a

growth in the numbers of people in the criminal

justice system for whom English is not their

first language, and report that women and girls

tend to have higher needs in this area as a

result of more restricted access to education.

This also has an impact on women’s ability

to understand decisions made in relation to

criminal cases and immigration status.

34

Girls from minority ethnic groups

Prison inspection reports highlight concerns

about safety and access to support for women

from minority ethnic groups, who are more

likely to say they have been victimised by other

prisoners because of their ethnicity, at all prisons

except HMP East Sutton Park, where none of the

respondents said they had been so victimised.

35

Recorded rates of self-harm are higher among

white women in prison, representing over 90% of

incidents over the last ten years.

36

Women from

minority ethnic groups may be under-represented

in these statistics, for reasons including

under-reporting, or misreading of the range of

emotional responses that women may have to

trauma. However, there has been an increase

in the recorded rates of self-harm amongst

women from minority ethnic groups, in particular

amongst mixed ethnic women.

While there has been a sustained and

significant reduction in the numbers of young

people going into custody since 2008, as well

as a drop in young people entering the criminal

justice system, these benefits have not been

felt equally across ethnicities.

For Black girls, there

has been a smaller

reduction in

convictions over the

same period.

There has been an

drop over ten years

since 2006 in the

number of white girls

receiving convictions.

84.9%

73.5%

Women from minority ethnic

groups in the criminal justice

workforce

Regrettably there is no official data available

on the number of women from minority ethnic

groups working in the criminal justice system.

13

Counted Out

What does the evidence show?

Despite some progress, evidence of racial bias in criminal justice agencies persists. This was

recognised in January 2016 when David Cameron commissioned the Lammy review and again

in August 2016 by the Prime Minister when she ordered an audit of racial disparities in public

services.

The discrimination and disadvantage that women in the criminal justice system in England and

Wales may experience if they are from a minority ethnic background is multi-layered. There is a

tendency to consider mainly white women when addressing gender inequality, and mainly black

men when addressing racial inequality, but it is the interplay between gender and race inequalities

that affects Black, Asian and minority ethnic women.

all the women are white, all the blacks are men, but some of us are brave

37

This ‘intersectional discrimination’ plays out in all aspects of the lives of women from minority

ethnic groups.

38

They face additional barriers to accessing support in relation to experiences

of violence,

39

are more likely to live in poverty than white people and men from minority ethnic

groups,

40

and tend to earn less than these groups.

41

The disadvantages women generally face

with the criminal justice system, such as experiencing a greater likelihood of imprisonment than

men for first offences and non-violent offences, higher rates of remand and poorer outcomes on

release

42

, are compounded. Women from minority ethnic groups make up 11.9% of the women’s

population in England and Wales, but 18% of the women’s prison population.

43

(see Figures 1 and

2). There has been a gradual decline since 2012, when this was 22%, but it remains significant.

44

Writer bell hooks argues that

‘racist stereotypes of the strong, superhuman black woman’

45

have obscured the extent to which black women are likely

to be victimised.

37 Hull, Gloria T. (1982) All the women are white, all the blacks are men, but some of us are brave. New York: The Feminist Press

38 Imkaan & Ascent (2016) Safe Pathways? Exploring an intersectional approach to addressing violence against women and girls, London: Imkaan & Ascent

39 Imkaan (2016) Capital Losses: The state of the specialist BME Ending Violence against Women and Girls sector in London. London: Imkaan.

40 Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2011) Poverty and ethnicity: A review of evidence. York: JRF; Lankelly Chase (2015) Women and girls at risk: Evidence across the life course.

London: Lankelly Chase.

41 Fawcett Society (2017) Gender Pay Gap by Ethnicity in Britain – Briefing. London: Fawcett Society

42 Prison Reform Trust (2017) Why focus on reducing women’s imprisonment? London: PRT.

43 Table DC2101EW, Office for National Statistics (2012) 2011 Census, London: ONS; Table 1.4, Ministry of Justice (2016) Population bulletin: weekly 31 March 2017, London:

Ministry of Justice

44 Table A1.7, Ministry of Justice (2013) Prison population tables, London: Ministry of Justice

45 Hooks, b. (1984) ‘Black Women: Shaping Feminist Theory’ in Feminist Theory: From Margin to Centre. Boston: South End Press

14

Counted Out

Fig 2

Fig 1

Unrecorded

Chinese or other ethnic group

Black or Black British

Asian or Asian British

Mixed

White

Other ethnic group

Black/African/Caribbean/Black British

Asian/Asian British

Mixed/multiple ethnic group

White

-100%

-80%

-60%

-40%

-20%

0%

20%

Asian

Black

White

20162015201420132012201120102009200820072006

80%

82%

84%

86%

88%

90%

92%

94%

96%

98%

100%

201520142013201220112010200920082007200620052004

Unrecorded

Other

Mixed

Black

Asian

White

Fig 2

Fig 1

Unrecorded

Chinese or other ethnic group

Black or Black British

Asian or Asian British

Mixed

White

Other ethnic group

Black/African/Caribbean/Black British

Asian/Asian British

Mixed/multiple ethnic group

White

-100%

-80%

-60%

-40%

-20%

0%

20%

Asian

Black

White

20162015201420132012201120102009200820072006

80%

82%

84%

86%

88%

90%

92%

94%

96%

98%

100%

201520142013201220112010200920082007200620052004

Unrecorded

Other

Mixed

Black

Asian

White

88%

81.6%

1.4%

4.6%

6.7%

3.9%

3.0%

8.9%

0.8%

0.6%

0.4%

Figure 1: Women in England and Wales by ethnic group; 2011 Census

46

Figure 2: Women in custody in England and Wales by ethnic group; 2016 prison

population statistics

47

These figures represent a snapshot number of women in prison at any one time. Receptions

data would more accurately reflect the numbers of women going into custody over a period

of time, including those on remand, recall and on short sentences. Our knowledge about the

race and ethnicity of women being sent to prison is limited by the Ministry of Justice’s failure to

publish prisons receptions data with a breakdown by ethnicity and gender. This in turn constrains

progress in addressing disproportionality.

46 Table DC2101EW, Office for National Statistics (2012) 2011 Census, London: ONS

47 Table 1.4, Ministry of Justice (2017) Population bulletin: weekly 31 March 2017, London: Ministry of Justice

15

Counted Out

The law on equality

Equality for women and girls from minority ethnic groups in the criminal justice system is a well

established legal requirement throughout the UK. The public sector equality duty requires public

authorities, when developing policies and services, to demonstrate due regard to the need to

eliminate discrimination against people with protected characteristics including sex and race.

This entails minimising disadvantage, taking steps to meet their needs and encouraging their

involvement in public life.

48

Section 10 of the Offender Rehabilitation Act 2014 stipulates that in England and Wales specific

arrangements must be made to meet the particular needs of female offenders in the provision of

probation services, in compliance with the equality duty.

49

Compliance with these equality duties requires the collection, analysis and publication of data on

the workings of the criminal justice system, disaggregated by gender and race.

Count minority ethnic women in - the importance of data

More than a decade ago the Fawcett Society’s Good Practice Guidelines

50

identified a lack of

data as a critical barrier to improving provision for women from minority ethnic groups in the

criminal justice system, stating that most services had inadequate monitoring and evaluation

frameworks. Measures to tackle inequalities can only be evidenced if sufficient data is collected

and monitored.

Very little of the data published by the Ministry of Justice is disaggregated by both gender and

ethnicity. Inconsistent ethnic categories are used by the police and prison services so it is not

always possible to analyse and compare data at different points in the criminal justice system.

The shortcomings apply to capturing sentencing outcomes, prison receptions, remand, recall

and release data, and in identifying the needs of women in prison and on release and women on

community orders.

Also unhelpful is a lack of rigour in recording ethnicity: overall it is unrecorded for 22% of women

first time entrants to the criminal justice system.

51

The area with the largest proportion of women

first time entrants whose ethnicity goes unrecorded is West Yorkshire, where it is 31%. This

inconsistency between geographical areas should be investigated with a view to improving data

collection by criminal justice agencies.

Research has found that women from minority ethnic groups are under-represented as workers in

the criminal justice system,

52

but there is no current official data available on the number of Black,

Asian or minority ethnic women working in the criminal justice system - as magistrates or judges

or employed in the police, courts, prisons or probation services.

48 EHRC (2010) Equality Act 2010. London: EHRC.

49 Offender Rehabilitation Act (2014) Offender Rehabilitation Act 2014. The Stationery Office: Norwich

50 Fawcett Society (2006) Good practice in meeting the needs of ethnic minority women offenders and those at risk of offending. London: Fawcett Society

51 Offending History Data tool: First time entrants, May 2017: www.gov.uk/government/statistics/criminal-justice-system-statistics-quarterly-december-2016

52 Fawcett Society (2010) Realising rights: increasing ethnic minority women’s access to justice. London: Fawcett Society; LankellyChase (2014) Women and girls at risk:

Evidence across the life course. Yorkshire: DMSS

16

Counted Out

Professional guidance

Information available to staff in criminal justice agencies, such as the NOMS guide to working

with women offenders

53

and the Equal Treatment Bench Book for judges,

54

highlight the additional

disadvantage faced by women from minority ethnic groups but give very limited guidance about

how this should be addressed or ameliorated. There was no reference to women from minority

ethnic groups in the Ministry of Justice’s Strategic Objectives for Females Offenders in 2013 nor

in the update in 2014,

55

nor any reference to women in the NOMS Race Review in 2008.

56

The

Lammy review provides an opportunity to address these oversights.

Specialist provision for women from minority ethnic groups

There are few organisations either working exclusively with or running programmes specifically

for women from minority ethnic groups. Imkaan’s state of the sector report

57

highlights the effect

of government budgets cuts on dedicated organisations working to end violence against Black,

Asian and minority ethnic women and girls. As women have reported being more likely to access

support from these specialist services, and feeling safer to speak about their experiences within

them, their loss is unhelpful to improving outcomes.

Imkaan’s Safe Minimum Practice Standards

58

outline core principles for VAWG services working

with women from minority ethnic groups. These stipulate that service provision should be

developed ‘with an understanding of the impact of racism and discrimination in the lives of

women and girls within the context of violence.’ These principles and standards should be

considered by central and local government and criminal justice agencies when commissioning

services for women in contact with the criminal justice system, as well as by providers of women-

specific services.

53 NOMS (2012) A Distinct Approach: A guide to working with women offenders. London: Ministry of Justice

54 Judicial College (2013) Equal Treatment Bench Book. Chapter 9: Ethnicity, inequality and justice. London: Courts and Tribunals Judiciary

55 Ministry of Justice (2013) Strategic objectives for female offenders. London: Ministry of Justice

56 Ministry of Justice (2008) Race Review: Implementing Race Equality in Prisons – Five Years On. London: Ministry of Justice.

57 Imkaan (2016) Capital Losses: The state of the BME ending violence against women and girls sector in London. London: Imkaan

58 Imkaan (2016) Imkaan safe minimum practice standards: working with black and minority ethnic women and girls. London: Imkaan

17

Counted Out

The evidence in more detail

This section sets out the quantitative data available for women by ethnicity in order to give a

more detailed comparative account of racial disparities within the criminal justice system. While

this briefing concerns adult women, we include some data on girls from minority ethnic groups

as this has clear implications for the future adult female prison population.

59

Girls from minority ethnic groups

I feel like we have a double standard, it’s not just with the police or social services,

with the whole public sector… Like the police, if I’m in trouble or whatever, they’ll

come there super quick, they bug me, they’ll run me down, they’ll call me names…

Then, when I got robbed and called them, they were very willy-nilly… There was

never an explanation of what actions exactly they were going to take.

Young Black woman with experience of care and the criminal justice system

60

There was a 73.5% reduction in Black girls receiving convictions over ten years since 2006,

while for white girls there was an 84.9% reduction. Black girls make up 10.8% of all girls

entering the criminal justice system for the first time.

61

An accurate comparator is not readily

available for the general population.

Black girls are significantly more likely to be arrested than white girls. They are five times more

likely to be arrested for robbery, and over three times more likely to be arrested for fraud.

62

However, the numbers of girls are too few beyond the point of arrest to draw conclusions on

disproportionate treatment for specific offences. Nevertheless, research conducted in 2010

found that a disproportionate number of both victims and perpetrators of serious youth violence

in London are from minority ethnic communities.

63

For Asian girls the picture is mixed. While there was a 52.1% drop in convictions of Asian

girls over the ten year period as a whole, this masks a dramatic rise from 2015 to 2016, when

convictions rose by 50% in a year, from 38 girls in 2015 to 57 girls in 2016.

64

Black women

I just think in general outside of prison life women are treated lesser than men and I

think Black, Asian people are treated lesser than white people so if you are a Black

or Asian woman... You’re already at a disadvantage, a double disadvantage .

Woman from minority ethnic group in prison, quoted by Agenda and Women in Prison, 2016

65

59 ‘Women’ refers to those 18 years and over; ‘girls’ refers to those between 13 and 17 years of age

60 Prison Reform Trust (2016) In Care, Out of Trouble. London: Prison Reform Trust

61 Ministry of Justice (2017) Offending history data tool: First time entrants, December 2016, London: Ministry of Justice. Black girls make up 3.3% of the general population

of girls in England and Wales but this only includes girls aged 0-15, whereas the statistics for first time entrants includes girls aged 13 to 17.

62 Table A2.5, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

63 Race on the Agenda (2010) Female Voice in Violence Project: A study into the impact of serious youth and gang violence on women and girls. London: ROTA

64 Ministry of Justice (2016) Offending history data tool, September 2016, London: Ministry of Justice

65 This quotation is from a focus group: Cox, J. and Sacks-Jones, K. (2016) Double Disadvantage: The experiences of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic women in the criminal

justice system, London: Agenda and Women in Prison

18

Counted Out

Black women make up 3% of the female population in England and Wales, but 8.9% of the

women’s snapshot prison population

66

and 6.7% of women entering the criminal justice system

for the first time.

67

However national statistics are not the best measure of disproportionality,

given the significant regional variations in population diversity. For example, in London 9.8% of

women are Black

68

but Black women made up 20.7% of first time entrants to the criminal justice

system.

69

In West Yorkshire, where 1.8% of the general population of women are Black, at least

3.7% of women first time entrants are Black (but as already noted ethnicity is unrecorded for 31%

of women first time entrants in this region).

70

Numbers of Black women in prison have gradually declined since 2012, at a greater rate than all

women in prison.

71

However, this data should be treated with caution as they do not reflect the

numbers of women being received into prison over time.

Nearly a fifth (18%) of Black women receiving convictions in 2015 had no previous offences,

compared with 12% of white women.

72

Black women are more than twice as likely to be arrested as white women in the general

population but 10% less likely than white women to be proceeded against following an arrest.

73

This could suggest an over-use of arrest powers, where there is weaker evidence or for less

serious incidents that do not reach the threshold for public interest to prosecute.

Black women are 35% more likely than white women to plead not guilty.

74

Not guilty pleas may

indicate mistaken arrest, a lack of trust in the system or lack of legal advice.

75

They are likely to

lead to more severe sentencing. Focus groups conducted by Agenda and Women in Prison found

that women had not been aware that their sentence could be reduced with an early guilty plea.

76

Black women are 63% more likely than white women to be tried at the Crown Court.

77

Decisions

to try a case at the Crown Court are based on the seriousness and complexity of the case and,

in some cases, the preference of the defendant. Defendants may elect Crown Court trial due to

the common belief that a jury will be more sympathetic. However, Agenda and Women in Prison’s

research found that women from minority ethnic groups had concerns about jury bias where

juries had been dominated by older, white men.

78

66 Table DC2101EW, Office for National Statistics (2012) 2011 Census, London: ONS; Table 1.4, Ministry of Justice (2016) Population bulletin: weekly 31 March 2017, London:

Ministry of Justice

67 Ministry of Justice (2017) Offending history data tool: First time entrants, December 2016, London: Ministry of Justice

68 EE1: Estimated resident population by ethnic group and sex, mid-2009 (experimental statistics) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2011/may/18/

ethnic-population-england-wales accessed 13/06/17 (this data includes women aged 16 years and over)

69 Ministry of Justice (2017) Offending history data tool: First time entrants, December 2016, London: Ministry of Justice

70 EE1: Estimated resident population by ethnic group and sex, mid-2009 (experimental statistics) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2011/may/18/

ethnic-population-england-wales accessed 13/06/17 (this data includes women aged 16 years and over); Ministry of Justice (2017) Offending history data tool: First time

entrants, December 2016, London: Ministry of Justice

71 Table 1.4, Ministry of Justice (2017) Population bulletin: weekly 31 March 2017, London: Ministry of Justice; Table 1.4, Ministry of Justice (2013) Population bulletin: weekly 31

March 2013, London: Ministry of Justice

72 Ministry of Justice (2016) Offending history data tool, September 2016, London: Ministry of Justice

73 Table 5.1, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

74 T able 5.3, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

75 Centre for Justice Innovation (2017) Building Trust: How our courts can improve the criminal court experience for Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic defendants. London: CJI

76 Cox, J. and Sacks-Jones, K. (2016) Double Disadvantage: The experiences of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic women in the criminal justice system, London: Agenda and

Women in Prison

77 Table 5.3, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

78 Cox, J. and Sacks-Jones, K. (2016) Op Cit

19

Counted Out

Black women are 29% more likely than white women to be remanded in custody at the Crown

Court.

79

BAWSO

Bawso is an all Wales, Welsh Government Accredited Support Provider, delivering

specialist services to people from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds who are affected

by domestic abuse and other forms of abuse, including female genital mutilation, forced

marriage, human trafficking and prostitution.

If convicted, Black women are 25% more likely than white women to receive a custodial

sentence.

80

There are broader consequences of this, as Black women are particularly likely to be

single mothers. More than half of Black families in the UK are headed by a lone parent, compared

with less than a quarter of white families and just over a tenth of Asian families.

81

Despite the law’s

requirement that the welfare of children affected should be considered in sentencing,

82

many

women in the focus groups conducted by Agenda felt that their family circumstances had not

been considered in their sentences.

83

There is particularly marked disproportion in the experience of Black women in the Crown Court

for drugs offences. These defendants are 84% more likely than white women to be remanded in

custody, despite no significant difference in conviction rates, and then more than twice as likely

(127% more) to receive a custodial sentence than white women.

84

HIBISCUS INITIATIVES

Hibiscus Initiatives aims to improve the quality of life for those who are marginalised by

language and culture by increasing awareness of the prison system and their rights by

enabling them to access and exercise these rights. They provide a wide range of services to

Black, Asian, minority ethnic and refugee women and foreign national women in UK prisons,

and their goal is to ensure that the client’s transition from prison back into the community is

as smooth as possible.

Black women are nearly six times as likely as white women to be arrested for fraud, and three

times as likely as white women to be remanded in custody at the Crown Court for fraud offences,

despite, again, similar conviction rates. Although Black women are over twice as likely to be

arrested for violence against the person as white women, they are 46% more likely to plead not

guilty at Crown Court, and 15% less likely to be convicted.

85

79 Table 5.3, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

80 Table 5.3, Ministry of Justice (2016) ibid

81 HM Chief Inspector of Prisons (2009) Race relations in prisons: responding to adult women from black and minority ethnic backgrounds, London: The Stationery Office

82 Prison Reform Trust (2015) Sentencing of mothers: improving the sentencing process and outcomes for women with dependent children. London: Prison Reform Trust

83 Cox, J. and Sacks-Jones, K. (2016) Double Disadvantage: The experiences of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic women in the criminal justice system, London: Agenda and

Women in Prison

84 Table 5.3, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

85 Table A2.13, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

20

Counted Out

Asian women

…we cannot assume that because the family provides the obvious everyday locus

for expressing ambiguities over female autonomy, that it should itself be regarded as

pathogenic; the ambiguities may be less ‘cultural’ than political in a wider sense, less

about the individual women challenging their family values than about their economic

experiences and actions outside of the family, including racism and tacitly restricted

opportunity.

Voluntary sector professional

86

Asian women make up 6.7% of the female population in England and Wales, and 3.9% of the

snapshot women’s prison population. Although this is an under-representation, numbers of Asian

women in prison have increased by 9% since 2012, compared with a 5.7% decrease in the overall

numbers of women in prison.

87

Asian women made up 4.2% of women entering the criminal justice system for the first time in

2016, but 9.1% of first time entrants in London, where they comprise 12.4% of the women’s

population. In the West Midlands however, where Asian women represent 7.5% of the women’s

population, they are 12.2% of first time entrants to the criminal justice system.

88

Forty per cent of Asian women receiving convictions in 2015 had no previous convictions,

compared with 12% of white women. Only 15% of Asian women had more than ten previous

convictions, compared with 43% of white women.

89

SOUTHALL BLACK SISTERS

Southall Black Sisters is a not-for-profit, secular and inclusive organisation, established

in 1979 to meet the needs of Black (defined here as Asian and African-Caribbean) women.

Its aims are to highlight and challenge all forms of gender related violence against women,

empower them to gain more control over their lives; live without fear of violence and

assert their human rights to justice, equality and freedom. Although locally based, the

organisation’s work has a national reach and reputation.

SBS runs an advice, advocacy and resource centre in West London which provides a

comprehensive service to women experiencing violence and abuse and other forms of

inequality. It offers specialist advice, information, casework, advocacy, counselling and self-

help support services in several community languages, especially South Asian languages.

Asian women and girls are less likely to be arrested than white women and girls across almost all

offence types.

90

The exception is for fraud offences, where Asian women are 26% more likely to

be arrested.

86 Quoted in: Bhardwaj, A. (2001) Growing up young, female and Asian in Britain: A report on self harm and suicide. Feminist review No. 68, Summer 2001, pp. 52-67

87 Table DC2101EW, Office for National Statistics (2012) 2011 Census, London: ONS; Table 1.4, Ministry of Justice (2016) Prison population: weekly 31 March 2017, London:

Ministry of Justice; Table 1.4, Ministry of Justice (2013) Prison population: weekly 31 March 2013, London: Ministry of Justice

88 EE1: Estimated resident population by ethnic group and sex, mid-2009 (experimental statistics) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2011/may/18/

ethnic-population-england-wales accessed 13/06/17 (this data includes women aged 16 years and over); Ministry of Justice (2017) Offending history data tool: First time

entrants, 18 May 2017, London: Ministry of Justice

89 Ministry of Justice (2016) Offending history data tool, September 2016, London: Ministry of Justice

90 Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

21

Counted Out

Asian women are 49% less likely to be arrested than white women, and Asian girls are 75% less

likely to be arrested than white girls. Furthermore, Asian women are 29% less likely than white

women to be charged by the Crown Prosecution Service following arrest, and 36% less likely than

white women who have been charged, to be proceeded against.

91

Stereotypes of Asian women as demure and compliant may influence the low arrest and charging

rates. However, the fact that they are then more than twice as likely to be tried at Crown Court

than white women

92

suggests that once Asian women appear in court as defendants, their offence

may be viewed as more serious than that of a white woman.

Asian women are 51% more likely than white women to plead not guilty at Crown Court,

93

the

highest rate of any ethnic group. Of those cases heard in the magistrates’ court, Asian women

are 42% more likely than white women to be convicted.

94

This is interesting in light of a study of

the impact of race and gender on school children, which found that Asian girls were disciplined

more severely for defying the ‘quiet Asian female’ stereotype.

95

This stereotype may also affect

experiences in custody. Agenda report that a woman in their focus group said her complaint of

racial discrimination had been ignored because ‘you’re seen as the quiet Asian girl’.

96

The data does not show custodial sentencing of Asian women to be disproportionate across all

offence types in comparison with the sentencing of white women, at magistrates’ or at Crown

Court.

97

However, as first time entrants to the criminal justice system, Asian women receive more

severe sentences. In 2016, 28.6% of Asian women received custodial or suspended sentences,

in comparison with 17.5% of white women, while 32% of Asian women and 44.7% of white

women were sentenced with a fine.

98

While the numbers of women convicted for different

offences are too small to analyse, it is possible that more severe sentencing reflects greater

numbers of foreign national women within this group.

Once in custody, Asian women face additional stigma from their community, for themselves and

their families ‘because in the Asian community, a woman, oh no, a woman doesn’t go to prison.

Maybe men, they say prisons are made for men and not for women.’

99

This is echoed in the

research conducted by the Muslim Women in Prison project.

100

The Lammy review has reported that Asian girls are significantly less likely to be arrested

than white girls, but the numbers are too small at the point of sentencing to be analysed for

disproportionality. However, a look at the numbers of girls receiving convictions over the past ten

years raises concerns about the implications for Asian girls. (See Figure 3).

91 Table 5.1, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

92 Table 5.3, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

93 ibid

94 Table 5.2, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

95 Connolly, P. (1998) Racism, Gender Identities and Young Children. London: Routledge

96 Cox, J. and Sacks-Jones, K. (2016) Double Disadvantage: The experiences of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic women in the criminal justice system, London: Agenda and

Women in Prison

97 Table 5.2 & 5.3, Ministry of Justice (2016) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic disproportionality in the Criminal justice system in England and Wales. London: Ministry of Justice

98 Ministry of Justice (2016) Offending history data tool, September 2016. London: Ministry of Justice

99 Cox, J. and Sacks-Jones, K. (2016) Double Disadvantage: The experiences of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic women in the criminal justice system, London: Agenda and

Women in Prison

100 Buncy, S. and Ahmed, I. (2014) Muslim Women in Prison. Second Chance Fresh Horizons: A study into the needs and experiences of Muslim women at HMP & YOI New Hall

& Askham Grange prisons during custody and post-release, Bradford: HPCA and Khidmat Centres: https://muslimhands.org.uk/_ui/uploads/kqe5a9/MWIP_Report.pdf

22

Counted Out

Fig 2

Fig 1

Unrecorded

Chinese or other ethnic group

Black or Black British

Asian or Asian British

Mixed

White

Other ethnic group

Black/African/Caribbean/Black British

Asian/Asian British

Mixed/multiple ethnic group

White

-100%

-80%

-60%

-40%

-20%

0%

20%

Asian

Black

White

20162015201420132012201120102009200820072006

80%

82%

84%

86%

88%

90%

92%

94%

96%

98%

100%

201520142013201220112010200920082007200620052004

Unrecorded

Other

Mixed

Black

Asian

White

Figure 3: Percentage change in numbers of girls under 18 receiving convictions

since 2006

101

Women of Muslim faith

…when I’m released their duty stops at the gate but I get another sentence

from the community and that lasts forever!

Muslim woman in prison, quoted by the Muslim Women in Prison Project, 2014

102

On 31 March 2017, there were 251 Muslim women in prison, according to data published by

the Ministry of Justice.

The proportion of Muslim women in custody has increased from 5.2% to

6.3%, over three years since March 2014 (203 women).

103

This is currently the only published data disaggregated by religion. However, HMIP survey

responses from women’s prisons give some indication of the challenges this group of women

may be facing in custody. Women from minority ethnic groups were more likely than white women

to identify as Muslim at all the prisons, revealing a group of women at risk of gender, racial and

religious discrimination. At HMP Foston Hall, where 23% of women from minority ethnic groups

are Muslim, 9% of women from minority ethnic groups said they had been victimised by other

prisoners because of their religious belief, and 5% of women from minority ethnic groups said that

they had been victimised by staff for this reason.

104

101 Ministry of Justice (2016) Offending history data tool, September 2016, London: Ministry of Justice

102 This quote is taken from the testimony of a Muslim woman in prison who was assisted by the Muslim Women in Prison project. Op Cit.

103 Table 1.5, Ministry of Justice (2014) Prison population: 31 July 2014, London: Ministry of Justice

104 HMP Foston Hall (June 2016)

23

Counted Out

MUSLIM WOMEN IN PRISON PROJECT

Muslim Women in Prison is a pioneering multi-agency project of Huddersfield Pakistani

Community Alliance in partnership with Khidmat Centres in Bradford.

Workers provide advocacy and support to Muslim women in HMP New Hall, HMP Askham

Grange, HMP Bronzefield and HMP Peterborough. Their work includes support with Islamic

divorce, access to children, and immigration, inheritance and other legal matters.

This work has also formed the research for the report, ‘Muslim Women in Prison,’ which

has raised awareness of the barriers faced by Muslim women in HMP New Hall and HMP

Askham Grange. Their research has shown that Muslim women face not only discrimination

from others in custody, but also discrimination from within their own communities. The

women they work with face additional barriers including increased isolation from families,

resulting from the perception that they bring shame and dishonour to their communities.

They are often fearful of violence and reprisal from their families, and some are unable to

return home after release from prison.

‘Mixed ethnic’ women

Through my own personal experiences, I don’t think everyone’s treated the same. I

think as much as we have to educate ourselves, the police need to be educated as

well, be more sensitive.

Woman in prison, quoted by Agenda and Women in Prison, 2016

105

In the 2001 Census, 48% of those identifying in the ‘mixed ethnic’ group identified as Mixed

White and Black Caribbean or Mixed White and Black African, and 29% identified as Mixed White

and Asian.

106

These proportions may not, however, correlate with the identities of those women

coming into contact with the criminal justice system.

It is important to note that individuals may define themselves as ‘mixed ethnic’ while also

identifying as Black or Asian. Individuals may also be viewed by others as Black or Asian

irrespective of how they choose to define themselves. Therefore women within the ‘mixed ethnic’