RESEARCH REPORT

New Orleans Students’

Commute Times by Car,

Public Transit, and School Bus

Jane Arnold Lincove Jon Valant

UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, BALTIMORE COUNTY BROOKINGS INSTITUTION

September 2018

E D U C A T I O N P O L I C Y P R O G R A M

ABOUT THE URBAN INSTITUTE

The nonprofit Urban Institute is a leading research organization dedicated to developing evidence-based insights

that improve people’s lives and strengthen communities. For 50 years, Urban has been the trusted source for

rigorous analysis of complex social and economic issues; strategic advice to policymakers, philanthropists, and

practitioners; and new, promising ideas that expand opportunities for all. Our work inspires effective decisions that

advance fairness and enhance the well-being of people and places.

Copyright © September 2018. Urban Institute. Permission is granted for reproduction of this file, with attribution to

the Urban Institute. Cover image by Dlewis33/iStock.

Contents

Acknowledgments iv

Executive Summary v

New Orleans Students’ Commute Times 1

Motivation 1

Context 2

School Choice Policy 2

Transportation Policy 3

Research Methods 4

Findings 7

Commute Times 7

School Bus Pickup Times 10

Discussion 12

Long and Early Commutes for Some Despite Guaranteed Transportation 13

A Need for More Information about Student Transportation Times 13

Public Transit Alternative 14

Varying Bus Schedules and Ride Lengths 14

Notes 16

References 17

About the Authors 18

Statement of Independence 19

IV

A C K N O W L E D G M E N T S

Acknowledgments

This report was funded by the Walton Family Foundation. We are grateful to them and to all our

funders, who make it possible for Urban to advance its mission.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute,

its trustees, or its funders. Funders do not determine research findings or the insights and

recommendations of Urban experts. Further information on the Urban Institute’s funding principles is

available at urban.org/fundingprinciples.

We are grateful to Caitlin Dermody, Bethany Kirkpatrick, Kiki Malomo-Paris, and Francesca Royal

for excellent research assistance. Kristin Blagg, Matthew Chingos, Gabriela Fighetti, Douglas Harris,

and John White provided helpful comments on an earlier draft. All errors are our own.

E X E C U T I V E S U M M A R Y

V

Executive Summary

School choice reforms aim to provide families with expanded opportunities and influence in public

education. However, policies that formally offer school choice can be constrained by conditions that

limit families’ choices in practice. One of those conditions is geography. Students cannot opt into

schools if they cannot reasonably get to them in the morning or get back home in the afternoon. Unsafe,

unaffordable, or burdensome commutes can prevent schools from being truly available to families. This

makes transportation a vital characteristic of school choice in practice.

In this study, we examine how students travel to school in the nation’s most market-driven school

system. We examine actual school bus routes in New Orleans, where students are not assigned to a

school based on their home address, and over 90 percent of public school students attend a charter

school. In New Orleans, schools are required to accept students regardless of where they live and to

bear the cost of “adequate and free” transportation for all students. Most schools enrolling elementary-

age children provide school buses, and high schools provide either school buses or public transit tokens.

We collected school bus routes for 17 charter and district-run schools in New Orleans. From these,

we estimate how much time students spend on school buses and how early their commutes to school

begin. We compare school bus routes with direct car drives or public transit (city buses and streetcars).

We find the following:

The median time for a school bus to get from a bus stop to school is 35 minutes. Round trip, this

amounts to about 6 hours per week that a typical child spends on a school bus. About 25

percent of school bus rides last over 50 minutes, and some rides last over 90 minutes.

In general, school buses take substantially less time than commuting via public transit. Car

travel is generally much faster than both school buses and public transit.

Schools vary in the efficiency of their bus routes. For some schools, school bus transportation is

faster (sometimes much faster) than public transit. For other schools, public transit is faster.

School bus pickups begin as early as 5:00 a.m.—approximately 2 hours before sunrise in the

winter—and most pickups are scheduled before 7:00 a.m.

These results confirm anecdotal evidence about long rides and early wake-up times for some New

Orleans students who attend schools far from home. To some extent, this might be an inescapable—and

perhaps acceptable—downside to enabling students to attend schools across the city. However, we find

that even some students who live close to school have long bus rides and early pickup times because of

VI

E X E C U T I V E S U M M A R Y

circuitous routes. This suggests that school and system leaders might have opportunities to make

student transportation more time efficient. It also suggests that parents could benefit from having

information about travel time, as well as school location, to make informed school choices.

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

1

New Orleans Students’

Commute Times

Motivation

School choice reforms aim to provide families with expanded opportunities and influence in public

education. The ability to select a school from multiple options allows families to choose based on

individual preferences and children’s unique educational needs. In addition, the ability of families to exit

failing public schools might, in theory, create incentives for school improvement. However, policies that

formally offer school choice can be constrained by conditions that limit choices in practice. One of those

conditions is geography. Put simply, students cannot choose schools if they cannot reasonably get to

them in the morning and get back home in the afternoon. Unsafe, unaffordable, or burdensome

commutes can prevent schools from being truly available to families. This makes transportation a vital

characteristic of school choice in practice.

In a zoned, residence-based school system, access to each school is generally limited to students in a

small radius around a school, where every zoned student can reach the school on foot or by a short car

or bus ride. In a choice-oriented system, families are encouraged to consider schools farther from home,

and transportation to and from school creates new challenges. Low-income families are often the

intended beneficiaries of school choice policies, but poor families have lower rates of car ownership

than wealthier families and often have inflexible work schedules that cannot accommodate taking

children to schools far from home. With the reality that poor families disproportionately live near

underperforming public schools (and are unable to pay for private schooling), transportation

considerations likely limit many students’ educational opportunities.

For decades, tens of millions of public school students in the US have relied on school buses to get to

and from school each day. Despite their central role in public education, school buses have played a

relatively minor role in the implementation of school choice. Most charter schools are not required to

provide school bus transportation, and many choose not to provide it. The direct cost of busing students

from far away can be high, and charter school policies typically place these costs on school operators.

There are also indirect costs to students in the form of hours spent on the bus instead of playing or

doing homework and lost sleep because of early pickup times.

2

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

These issues present difficult questions to policymakers and system leaders in education systems

with school choice programs. For example, should they offer citywide services, such as school bus

transportation or public transit passes, or should they give schools discretion to determine their

transportation offerings? To whom should these services be available? And what are the benefits and

costs associated with the various options?

This study examines student transportation in New Orleans, the US city with the most market-

oriented school system. In New Orleans, where families are not assigned to schools based on their home

address, policymakers and school operators have grappled with how to make transportation accessible,

efficient, and affordable as families seek placements in schools across the city. They have opted for a

system that provides yellow school bus service to nearly all public schools citywide with direct costs

carried by school operators. Though this carries considerable financial and logistical costs for schools

(Buerger and Harris 2017), it has the potential to expand the options accessible to families. This

transportation model, like the broader school system in New Orleans, is highly decentralized and

unprecedented in the history of US public education.

In this study, we begin, in a small way, to address big questions about school busing in a choice-

based school system. We explore questions related to commute time by comparing the time that

students in New Orleans spend on school buses with the time that they would spend—starting at the

same place—to get to school by car or public transit.

Context

This study uses data on school bus and public transit routes to schools in New Orleans. The New

Orleans public school system offers the most comprehensive implementation of school choice in the US

and is the only system in the US that requires all schools to provide transportation in support of school

choice.

1

Here, we highlight some characteristics of the current system that are important for

understanding the role of transportation in school choice.

School Choice Policy

Over 90 percent of New Orleans’ public schools are charter schools, operated by over 40 independent

nonprofit organizations. At the time of our study, charter schools were authorized and governed by the

local Orleans Parish School Board (OPSB), the state Recovery School District, and the state Board of

Elementary and Secondary Education. OPSB and Recovery School District also directly operated a small

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

3

number of schools. Unlike most districts in the US, children in New Orleans, from prekindergarten

through grade 12, have no zoned schools. Students are assigned to schools through a centralized

enrollment lottery and enrollment system, called OneApp, where families rank up to 12 preferred

schools. Students are assigned to their highest-ranked school where a seat is available. With few

exceptions, school admissions processes do not include academic or other entrance requirements,

making most schools in New Orleans available as options to families across the city.

New Orleans provides students no guarantee of a seat in a school near home, but most elementary

and middle schools offer geographic priority for a limited number of seats. The geographic priority

divides the city into several catchment zones, and students who live in a school’s catchment zone are

seated first for a subset of the school’s open seats.

Studies of parental preferences in New Orleans suggest that parents typically prefer schools closer

to home, all else equal, but are willing to travel to improve school quality (Harris and Larsen 2017;

Lincove, Cowen, and Imbrogno 2018). Oversubscription prevents some families from being placed in

schools they desire even as seats remain open in schools nearer their homes. About one-third of

applicants did not receive any of their top three choices in the main round of assignment for fall 2018.

2

Transportation Policy

New Orleans is a geographically large city with a choice-based education system, high levels of poverty

and crime, and a public transit system that is maligned for its unreliability and infrequent service,

especially in impoverished neighborhoods.

3

In this context, policymakers have relied on schools—rather

than public transit systems or families’ personal transportation options—to provide school

transportation.

The City requires all charter schools to provide “free and adequate” transportation to and from

school for all students. In practice, most schools enrolling elementary students fulfill this requirement

by providing school buses. High schools provide either school buses or tokens to use public transit.

Whatever strategy they choose, there is no district-level funding for transportation, so schools must

fund their transportation offerings via their per pupil funds or other sources. A study on the effects of

school reform on finance found that transportation is one of the greatest costs of New Orleans charter

schools, and that increased transportation costs citywide is one of the largest fiscal effects of the

transition to a market-based school system (Buerger and Harris 2017).

4

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

There are also costs for students who depend on school buses or public transit to get to school.

News reports from New Orleans provide anecdotal accounts of challenges related to school

transportation. Some parents of students who ride school buses report long school bus rides, early

pickup times, and concerns about safety.

4

Many perceive public transit in New Orleans as an unreliable

alternative, and some school campuses are not well served by city bus routes.

5

Research Methods

To examine the time that students spent on buses, we collected bus route data for several district and

charter schools across the city. Route information is not centrally collected by the school district, so we

obtained these routes directly from individual schools, either from school websites or through requests

to school staff. In all, we collected and coded routes for 17 New Orleans charter schools from the 2014–

15, 2015–16, or 2016–17 school years. For 9 of these 17 schools, we have complete school bus route

information, including the times and locations of all morning stops and the final drop-off time at school.

For the remaining 8 schools, the schedules report times and locations of bus stops but not the final

drop-off time at the school. Therefore, we include only 9 schools (with 85 bus routes and 1,335 bus

stops) in analysis of transit times to schools, and all 17 schools (with 152 bus routes and 2,338 stops) in

analysis of pickup times.

Figure 1 plots the locations of the nine schools that have drop-off time information; we overlay the

map of the city’s median income by census tract. New Orleans is a large city geographically, with a

relatively dense and racially and economically segregated population. Low-income African American

communities are concentrated in the west, central city, and near-east tracts. Lightly populated

swampland extends far to the east. The district is geographically divided by the Mississippi River, and

commutes between the two sides are made via a single, busy traffic bridge or by ferry. Our nine schools

include eight on the East Bank and one on the West Bank.

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

5

FIGURE 1

Map of School Locations and Mean Family Income by Census Tract

URBAN INSTITUTE

Source: Income data are from American Community Survey five-year estimates, 2012–16.

Notes: Each dot represents a school for which we have complete bus route information. Unshaded tracts do not have a median

household income data available.

These schools may not be fully representative of the broader New Orleans school population, but

they include locations across the most populous parts of New Orleans (where most schools are located)

and routes that transport students across the city. Moreover, the schools we examine in this report

appear similar with respect to size, student demographics, school performance ratings, and structure to

the full population of New Orleans public schools (table 1).

6

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

TABLE 1

Characteristics of New Orleans Schools

Characteristics

All New Orleans

public schools

Schools with

routes showing

arrival times

Schools with

routes lacking

arrival times

Student enrollment

Number of students (mean)

513

519

482

Student demographics

Black

0.85

0.86

0.88

White

0.07

0.06

0.01

Hispanic

0.06

0.07

0.10

Free or reduced-price lunch

0.74

0.74

0.80

School performance

State report card grade (GPA)

1.96

2.00

2.00

School performance score (mean)

75.1

76.0

76.0

Grade levels offered

K–8

56

9

7

9–12

25

0

2

School types

Charter schools authorized by:

Orleans Parish School Board (OPSB)

19

2

1

Recovery School District

51

5

6

Board of Elementary and Secondary

Education or governor

6

0

1

OPSB direct-run school

7

2

0

Total schools

83

9

8

Notes: Summary statistics are based on author calculations of Louisiana Department of Education (LDOE) enrollment data for the

2015–16 school year. Bus route information comes from the 2014–15 through 2017–18 school years. State report card grades

are converted to grade points on a four-point scale: A = 4, B = 3, C = 2, D = 1, F = 0. Report card grades and school performance

scores were determined by LDOE based on testing in spring 2016 and are based primarily on student proficiency levels. One

school had both K–8 and 9–12 grade levels and is represented in each row. The analyses presented in figures 1 through 3 use nine

schools with full bus schedules. The analyses presented in figure 7 use the 17 schools for which we have routes, whether they

have arrival times or not.

We calculated the time that students spend on buses using the provided bus route information. For

each school bus stop, we found the time difference between when the bus picked up students and when

it dropped off those students at school. In this way, we rely on school-provided routes (the same

information provided to families) for estimates of pickup and drop-off times. Students’ actual commute

times to school likely exceed the times that we use, since we cannot observe what time students leave

home to reach their bus stop on time.

6

Next, we calculated the times, according to Google Maps, that students would have spent going

from each school bus stop to school by car or public transit. We geocoded the bus stop intersections

using the HERE Maps API (and school locations using Google Maps). We then used Google APIs to

estimate the amount of time it would take by car and by public transit to travel directly to school from

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

7

that bus stop location, with instructions to arrive 20 minutes before school’s start time on Wednesday,

October 3, 2018 (chosen to represent a typical school day).

For New Orleans, which does not have a subway system, the public transit routes consist of time

spent walking to transit stops, waiting at stops, and riding to school on city buses or streetcars.

7

Notably, the relative efficiency of public transit could differ in cities with different types of public transit

systems.

8

Findings

Commute Times

First, we compare commute times by school bus, car, and public transit, assessing transit times from the

same starting points (school bus stop intersections) and end points (schools).

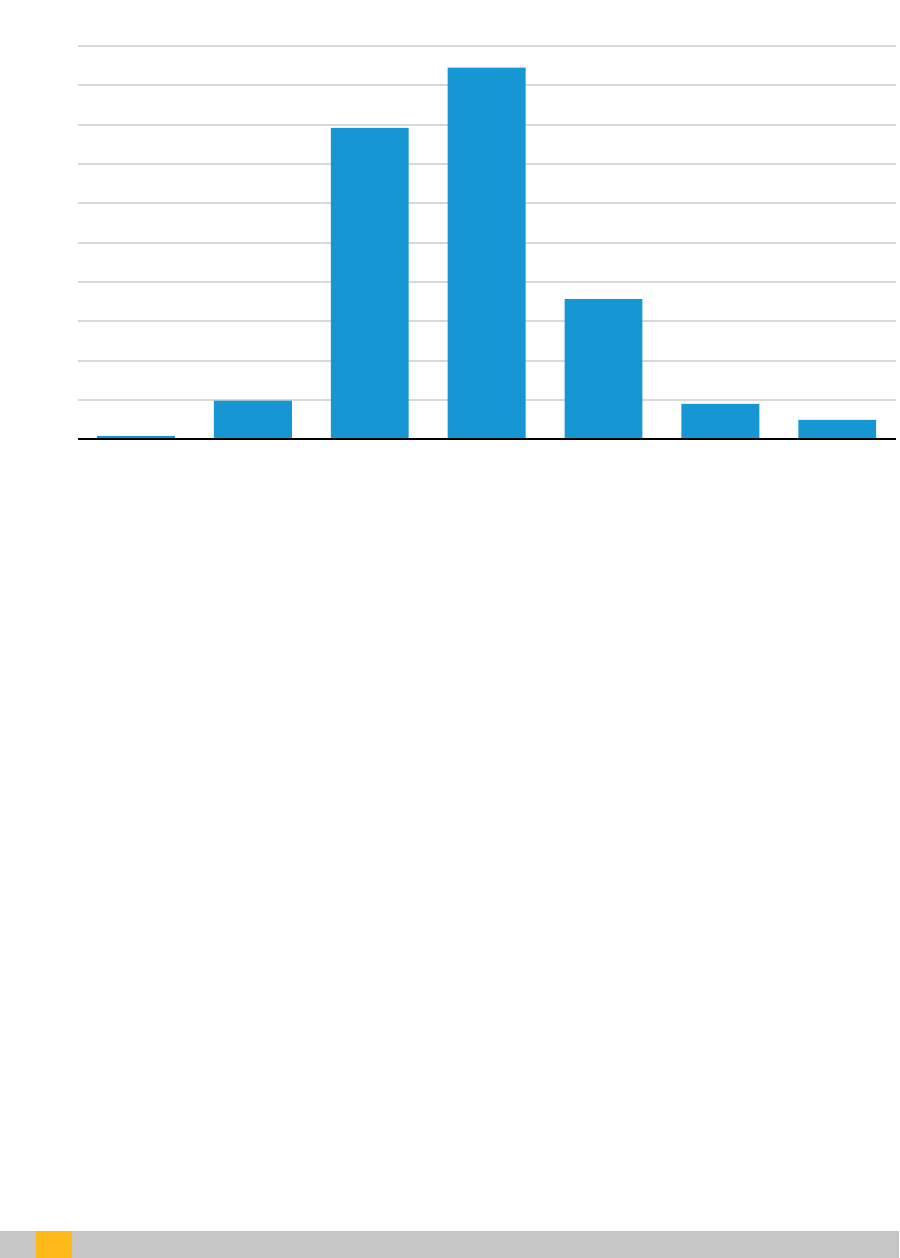

Figure 2 illustrates the range of commute times by each mode of transit. It shows data for the nine

schools for which we have school arrival times. The observations consist of individual bus stops, with

each stop receiving equal weight.

9

We find that the median commute time by school bus (35 minutes) is

considerably longer than the time by car (14 minutes) and shorter than the time by public transit (47

minutes).

Figure 3 displays the car and public transit commute times from each stop (using the fastest route

identified by Google Maps), relative to the time it takes the school bus to commute from that stop. Each

dot represents a school bus stop. Each yellow dot compares the commute from a bus stop via school bus

(x-axis) with the commute via public transit (y-axis). Each blue dot compares the commute from a bus

stop via school bus (x-axis) with the commute directly via public transit (y-axis). The easiest way to

interpret this figure is to start at the x-axis and work upward. For example, the dots directly above the

50-minute line on the x-axis show how long it takes by public transit (in yellow) and by car (in blue) to

arrive at school from a school bus stop that will take 50 minutes to get to school.

The black reference line depicts a perfect 1:1 relationship where car or public transit time would be

exactly equal to school bus time. Points below the line indicate cases in which school bus commutes are

longer than alternatives. Points above the line indicate cases in which school bus commutes are shorter

than alternatives.

8

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

FIGURE 2

Morning Commute Times for Selected New Orleans Schools

URBAN INSTITUTE

FIGURE 3

Commute Times by School Bus, Car, and Public Transit

URBAN INSTITUTE

Notes: Shows morning commute times from school bus stops to nine New Orleans schools. School bus times calculated using

school-provided routes. Car and public transit times calculated using Google Maps.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

School bus Car Public transit

Mode

Minutes

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Reference line Minutes by car Minutes by public transit

Minutes by school bus

Minutes by car or public transit

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

9

In nearly all cases, car commutes are shorter than scheduled school bus commutes. This is expected

because car routes go directly to schools and buses make additional stops. More surprising is how weak

the association appears to be between car and school bus commute times. Bus stops with commute

times of over 50 minutes are often located less than 10 minutes from the school by a direct route. This

suggests that many students slowly weave their way across many stops without actually traveling very

far.

Most school bus routes are faster than public transit routes from the same intersection, but there is

a great deal of variation. In some cases, school bus commutes are much shorter than public transit

commutes. In other cases, the opposite is true. Figure 4 shows transit times for one school with school

buses that almost always get to school faster than public transit would from the same bus stops.

FIGURE 4

Commute Times to School with Time-Efficient School Buses

URBAN INSTITUTE

Notes: Shows morning commute times from school bus stops to one New Orleans school. School bus times calculated using

school-provided routes. Car and public transit times calculated using Google Maps.

Figure 5, in contrast, shows a school with buses that rarely get students to school faster than the

public transit system. Most of the yellow dots appear below the black line, indicating that school bus

commutes usually take longer—sometimes much longer—than public transit commutes would from the

same street intersection.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

Reference line Minutes by car Minutes by public transit

Minutes by school bus

Minutes by car or public transit

10

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

FIGURE 5

Commute Times to School with Time-Inefficient School Buses

URBAN INSTITUTE

Notes: Shows morning commute times from school bus stops to one New Orleans school. School bus times calculated using

school-provided routes. Car and public transit times calculated using Google Maps.

What accounts for the differences between these two schools is not clear. Both schools are within

three blocks of a city bus stop, but they might vary in how students are dispersed for bus routing

purposes, making the differences we observe largely outside of the schools’ control. However, it is

certainly possible that in a system this decentralized—where schools are tasked with making their own

transportation plans (or contracting with others who do)—some schools do a better job of designing and

implementing time-efficient bus plans. Buerger and Harris (2015) describe challenges in New Orleans

from economies of scale lost through decentralization. It could be that some schools would benefit from

having additional guidance from a district or other more centralized source of support.

School Bus Pickup Times

Some students spend a great deal of time on school buses, seeing much of the city through their daily

commutes. Figure 6 shows the stops for the route with the longest school bus ride in the time-inefficient

school from figure 5 (a school that, incidentally, closed in 2018). This particular bus picked up its first

student at 5:21 a.m. in the Algiers neighborhood, made 21 more stops, and then arrived at school at 6:59

a.m.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Reference line Minutes by car Minutes by public transit

Minutes by school bus

Minutes by car or public transit

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

11

FIGURE 6

School Bus Stops for a 98-Minute Ride through New Orleans

The circuitousness of this route—and surely many other routes in New Orleans—suggests

opportunities to reduce students’ commute times via alternate routing. This could make schools more

accessible to families who might wish to attend them. It also could allow students to sleep in a little later.

Of course, changing bus routes could have financial implications—a question that is beyond the scope of

this study’s data and analysis.

Figure 7 illustrates the distribution of bus stop pickup times for the broader set of 17 charter

schools for which we have some bus route information.

Pickup times for these routes range from about

5:00 a.m. to 8:30 a.m. The majority of pickups occur between 6:00 a.m. and 7:00 a.m. Although relatively

few students have pre–6:00 a.m. pickup times, most of these students need to arrive at the bus stop

before the sun rises (which typically occurs around 7:00 a.m. in October). All students in New Orleans

can receive free breakfast at school, so arrival times are designed to give students at least 20 minutes to

eat before school begins.

12

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

FIGURE 7

Morning Bus Stop Pickup Times

URBAN INSTITUTE

Notes: Shows school by pickup times in the morning for all 17 New Orleans public schools with bus stop information available.

Discussion

These data provide insights into the time and nature of students’ school bus commutes in a

decentralized, choice-based education system. Here, we highlight a few findings and their implications

for parents, schools, and policymakers:

1. Even in a city with generous school bus offerings, some students will spend a lot of time on

buses—and begin those rides very early.

2. Parents—and probably researchers—need better information about transportation.

3. Public transit is an alternative to consider, although it has costs of its own.

4. Not all bus schedules are equal.

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1,000

5:00–5:30 5:30–6:00 6:00–6:30 6:30–7:00 7:00–7:30 7:30–8:00 8:00–8:30

School bus pickup times

Number of bus stops

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

13

Long and Early Commutes for Some Despite Guaranteed Transportation

To some extent, longer commute times are inevitable in a large city that gives families more

opportunities to enroll their children in schools across the city. This could be a price worth paying to

weaken links between where children live and which schools they attend. Still, many students in New

Orleans, a city with generous school bus transportation, spend a lot of time commuting to and from

school.

For the routes we examine, school bus rides are about two-and-a-half times as long as car rides from

the bus stop intersection to school. Whether this difference is excessive is subjective, but for students

on longer routes, this can mean waking up very early—in extreme cases, arriving at a bus stop two hours

before sunrise—and spending a great deal of time on the bus. With a median one-way ride of 35 minutes

to school, students on these routes likely spend about six hours on the bus each week, nearly the

equivalent of a full school day. This is time not spent learning, sleeping, playing, or spending time with

family. Research indicates that waking up early for school reduces the hours a student sleeps, which has

negative effects on child development and school performance (Jacob and Rockoff 2011).

Disadvantaged students might especially benefit from later start times (Edwards 2012; Jacob and

Rockoff 2011).

A Need for More Information about Student Transportation Times

Studies of parental preferences in choice systems consistently show that distance to school is a strong

predictor of families’ school choices (Glazerman and Dotter 2017; Gross, DeArmond, and Denice 2015;

Harris and Larsen 2017; Hastings, Kane, and Staiger 2005). Controlling for other characteristics of their

options (such as school test performance), parents consistently prefer schools closer to home. In prior

research, this is measured either as the direct distance between home and schools or the estimated

driving distance. These studies have not had access to bus schedule data to measure the true commute

times for many students.

When choosing schools, parents might also estimate commute time by assessing distance from

home. This study indicates, however, that it can be difficult to accurately infer children’s commute time

from the school’s distance from home. The next year’s bus route information is rarely, if ever, available

to New Orleans parents as they choose schools. We observe a surprisingly weak relationship between

drive times and school bus commute times. A parent who is concerned about her child’s time on buses

might choose differently with better information available about bus commute times and might be less

likely to switch schools after enrolling because of a surprisingly long commute.

14

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

Public Transit Alternative

Many cities use public transit as the only transportation system that supports school choice. Depending

on local circumstances, including the safety and dependability of public transit systems, relying on the

city’s transportation system might be appropriate. School buses might be preferred for young children

and those who lack the ability to follow bus schedules, make transfers, and cope with delays or route

changes. But, for students who are sufficiently mature and independent, school buses and public transit

can be viable substitutes.

This study shows cases in which school buses are faster and cases in which public transit is faster.

Perhaps school bus transit times could be shortened through better route planning or more sharing of

buses or bus stops across schools. At the same time, public transit could be a more sensible choice for

some students and a less burdensome and expensive choice for schools. In a city like New Orleans,

schools might wish to offer students a choice of free transportation options that includes both school

buses and public transit. This could allow families to decide whether school buses or public transit are

better suited to their needs and tastes.

Varying Bus Schedules and Ride Lengths

Our results suggest that schools vary in how quickly their buses get children to school. Some schools

have routes with dozens of stops per bus. This could come at a cost to children who spend a substantial

amount of time on the bus.

One possible explanation for these variances is that longer bus routes are less expensive for

schools. All New Orleans schools are required to provide transportation, which includes either school

buses or public transit tokens for students who live more than one mile from school. However, there are

no regulations—and likely little guidance—regarding bus routing. In many cases, schools might face a

trade-off between the direct cost to the school of bus service and the indirect costs to families. For

example, in a related study, we found that one school that offered transit tokens, a less expensive option

for the school than school bus service, placed a large burden on students in long commute times.

10

A second explanation is that school administrators lack resources and expertise to coordinate

transportation efficiently. Of the two schools we highlighted, the school with faster routes is one of the

highest-rated, most-oversubscribed schools in New Orleans, and the school with slower routes recently

closed for poor performance. Decentralization requires school leaders to access expertise in many

aspects of school management. Creating efficient bus routes could be a difficult task that benefits from

N E W O R L E A N S S T U D E N T S ’ CO M M U T E T I M E S

15

a particularly unusual skill set. It involves weighing trade-offs in financial costs, the time that students

spend on buses, the convenience of bus stops to families’ homes, and other factors. Although bus

companies can help with routing, schools might benefit from additional supports from district offices,

charter school authorizers, or other organizations with expertise in student transportation.

This report offers a glimpse of the relative travel-time efficiency of school buses, public transit, and

cars in a city that has embraced school reforms and committed to providing free student transportation.

The report is limited in a number of ways, including uncertainty about the generalizability of these data,

both within New Orleans and beyond, and in the data we do not have, such as the financial cost of

alternate bus routes and transportation policies. However, we believe this report makes clear that

transportation policy and implementation decisions can have significant consequences for families.

These decisions can determine which schools are truly accessible to families, how early in the morning

and late in the afternoon students will commute, and how much time they spend in transit.

16

N O T E S

Notes

1

See Sims and Rossmeier (2015) for a detailed history of the changes to the New Orleans school system after

Hurricane Katrina.

2

“EnrollNOLA Sees Record Number of Applications to 2018-2019 OneApp,” news release, Louisiana Department

of Education, April 16, 2018, https://www.louisianabelieves.com/newsroom/news-

releases/2018/04/16/enrollnola-sees-record-number-of-applications-to-2018-2019-oneapp.

3

Jacob Anbinder, “How to Fix New Orleans Transit,” The Century Foundation, August 28, 2015,

https://tcf.org/content/commentary/how-to-fix-new-orleans-transit/?session=1.

4

Wilborn P. Nobles III, “Charter Schools Battle OPSB over Buses as Students Struggle to Get to Class,” Times-

Picayune, March 2, 2018,

https://www.nola.com/education/index.ssf/2018/03/einstein_student_transportatio.html; Wilborn P. Nobles III,

“Orleans School Board to Hire Consultant to Review School Transportation, Enrollment,” Times-Picayune,

December 14, 2017,

https://www.nola.com/education/index.ssf/2017/12/opsb_study_on_transportation_e.html.

5

Jon Valant and Jane Arnold Lincove, “Barriers That Make Charter Schools Inaccessible to Disadvantaged

Families,” Brown Center Chalkboard (blog), Brookings Institution, March 16, 2018,

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2018/03/16/the-barriers-that-make-charter-

schools-inaccessible-to-disadvantaged-families/.

6

Orleans Parish School Board (OPSB) policy required students in grades 3 through 12 who were eligible for bus

transportation (i.e., lived more than one mile from school) to be picked up at a bus stop within one mile of their

home. Younger students would be picked up at the nearest safe corner. Students with disabilities would be

provided transportation in accordance with their individualized education programs. Rules about pickup

locations appear less uniform and straightforward in non-OPSB schools (Urban Institute Student Transportation

Working Group 2017).

7

Our analyses of public transit time consider city buses and street cars (whatever combination of city bus and

streetcars is fastest according to Google Maps). City buses cover much more of New Orleans than streetcars.

8

A previous report in this series compares driving times and public transit times across two cities with subway

systems (New York and Washington, DC) and three cities without them (Denver, Detroit, and New Orleans)

(Urban Institute Student Transportation Working Group 2018). Public transit times are closer to driving times in

the cities with subway systems. This could reflect the subway systems being more efficient but could also reflect

car commutes being slower in New York and DC.

9

By weighting each stop equally, routes and schools with more stops receive greater weight than routes with

fewer stops. We do not include any student weights, primarily because we do not observe how many students

board the bus at each stop.

10

Valant and Lincove, “Barriers That Make Charter Schools Inaccessible to Disadvantaged Families.”

R E F E R E N C E S

17

References

Buerger, Christian, and Douglas Harris. 2015. “How Can Decentralized Systems Solve System-Level Problems? An

Analysis of Market-Driven New Orleans School Reforms.” American Behavioral Scientist 59 (10): 1246–62.

———. 2017. How Did the New Orleans School Reforms Influence School Spending? New Orleans: Education Research

Alliance for New Orleans.

Edwards, Finley. 2012. “Early to Rise: The Effect of Daily Start Times on Academic Performance.” Economics of

Education Review 31 (6): 970–83. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2012.07.006.

Glazerman, Steven, and Dallas Dotter. 2017. “Market Signals: Evidence on the Determinants and Consequences of

School Choice from a Citywide Lottery.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 39 (4): 593–619.

Gross, Betheny, Michael DeArmond, and Patrick Denice. 2015. Common Enrollment, Parents, and School Choice: Early

Evidence from Denver and New Orleans. Making School Choice Work Series. Seattle: Center on Reinventing Public

Education.

Harris, Douglas N., and Matthew F. Larsen. 2017. Demand, Information, and the Market for Schooling: Evidence on

Revealed Preferences from Post-Katrina New Orleans. New Orleans: Education Research Alliance for New Orleans.

Hastings, Justine S., Thomas J. Kane, and Douglas O. Staiger. 2005. “Parental Preferences and School Competition:

Evidence from a Public School Choice Program.” Working Paper 11805. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of

Economic Research.

Jacob, Brian A., and Jonah E. Rockoff. 2011. Organizing Schools to Improve Student Achievement: Start Times, Grade

Configurations, and Teacher Assignments. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Lincove, Jane A., Joshua M. Cowen, and Jason P. Imbrogno. 2018. “What’s in Your Portfolio? How Parents Rank

Traditional Public, Private, and Charter Schools in Post-Katrina New Orleans’ Citywide System of School

Choice.” Education Finance and Policy 13 (2): 194–226. doi:10.1162/edfp_a_00222.

Sims, Patrick, and Vincent Rossmeier. 2015. The State of Public Education in New Orleans: 10 Years after Hurricane

Katrina. New Orleans: Tulane University, Cowen Institute for Public Education Initiatives.

Urban Institute Student Transportation Working Group. 2017. Student Transportation and Educational Access: How

Students Get to School in Denver, Detroit, New Orleans, New York City, and Washington, DC. Washington, DC: Urban

Institute.

———. 2018. The Road to School: How Far Students Travel to School in the Choice-Rich Cities of Denver, Detroit, New

Orleans, New York City, and Washington, DC. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

18

A B O U T T H E A U T H O R S

About the Authors

Jane Arnold Lincove is an associate professor of public policy at the University of Maryland, Baltimore

County. Her work focuses on college access and market-based school reforms. She is a nonresident

research fellow at the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans at Tulane University and a research

affiliate of the Maryland Longitudinal Data System Center. Lincove holds an MPP from the University of

California, Los Angeles, and a PhD in public policy from the University of Southern California.

Jon Valant is a fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution. He studies

urban school choice policies and programs. Much of his work focuses on New Orleans, where he is a

nonresident research fellow at the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans at Tulane University.

Valant holds an MPP from the Harvard Kennedy School and an MA in political science and PhD in

education from Stanford University.

STATEMENT OF INDEPENDENCE

The Urban Institute strives to meet the highest standards of integrity and quality in its research and analyses and in

the evidence-based policy recommendations offered by its researchers and experts. We believe that operating

consistent with the values of independence, rigor, and transparency is essential to maintaining those standards. As

an organization, the Urban Institute does not take positions on issues, but it does empower and support its experts

in sharing their own evidence-based views and policy recommendations that have been shaped by scholarship.

Funders do not determine our research findings or the insights and recommendations of our experts. Urban

scholars and experts are expected to be objective and follow the evidence wherever it may lead.

2100 M Street NW

Washington, DC 20037

www.urban.org