CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU | SEPTEMBER 2022

Buy Now, Pay Later:

Market trends and

consumer impacts

1

Table of contents

Table of contents ............................................................................................................ 1

1. Executive Summary................................................................................................. 3

2. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 6

2.1 Product Definition ....................................................................................6

2.2 Background ...............................................................................................6

2.3 Summary of Report and Findings ........................................................... 8

3. Consumer Metrics ................................................................................................. 12

3.1 Customer Acquisition ............................................................................. 12

3.2 Application Flow/Underwriting ............................................................. 15

3.3 Account Management/Repayment......................................................... 21

4. Market Metrics and Trends ................................................................................... 31

4.1 Volume and Usage .................................................................................. 31

4.2 Unit Margins .......................................................................................... 36

4.3 Business Trends ..................................................................................... 42

5. BNPL and Consumer Financial Health ............................................................... 61

5.1 Introduction ............................................................................................ 61

5.2 Benefits ................................................................................................... 61

5.3 Overextension Risks .............................................................................. 64

6. Takeaways and Risks ............................................................................................ 70

6.1 Takeaways .............................................................................................. 70

6.2 Risks to Consumers and Other Market Participants .............................. 72

2

7. Appendix ................................................................................................................. 78

7.1 Merchant vertical, subvertical mapping .................................................78

7.2 Definitions of unit economics line items ................................................ 81

3

1. Executive Summary

Consumers have long used credit instruments to purchase goods and services. In recent years, a

fast-growing alternative to credit cards has emerged in a number of developed economies

around the world, including in the United States. This alternative is marketed as “Buy Now, Pay

Later” (BNPL).

BNPL is a form of credit that allows a consumer to split a retail transaction into smaller,

interest-free installments and repay over time.

1

The typical BNPL structure divides a $5o to

$1,000 purchase into four equal installments, with the first installment paid as a down payment

due at checkout, and the next three due in two-week intervals over six weeks. When a borrower

does not make these payments, many BNPL lenders charge late fees, often around $7 per missed

payment on an average loan size of $135.

In December 2021, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) issued market

monitoring orders to five lenders to provide data on their BNPL loans.

2

This market report

summarizes that data, individual and organizational submissions to the CFPB, and publicly

available sources to provide a review of BNPL’s marketplace importance and consumer impacts

in the United States.

3

Important metrics from the report include:

▪ The BNPL industry is in the midst of rapid growth. From 2019 to 2021, the number of

BNPL loans originated in the U.S. by the five lenders surveyed grew by 970 percent, from

16.8 to 180 million, while the dollar volume of those originations (commonly referred to

as Gross Merchandise Volume, or GMV) grew by 1,092 percent, from $2 billion to $24.2

billion.

▪ The industry mix of BNPL usage is diversifying. Apparel and beauty merchants, who had

combined to account for 80.1 percent of originations in 2019, only accounted for 58.6

percent in 2021.

1

In general, this report uses the term “borrower” to refer to a BNPL customer who has completed the process of

taking out a BNPL loan, and the terms “user” or “applicant” to refer to a BNPL customer who is browsing the platform

or is in the middle of a credit application that is not yet complete. It will also use the term “consumer” when referring

to general instances of individuals that may expand beyond the scope of BNPL.

2

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Opens Inquiry into ‘Buy Now, Pay

Later’ Credit (December 16, 2021), available at https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/consumer-

financial-protection-bureau-opens-inquiry-into-buy-now-pay-later-credit

3

This report was prepared by Martin Kleinbard, Jack Sollows, and Laura Udis, Office of Markets.

4

▪ 73 percent of applicants were approved for credit in 2021, up from 69 percent in 2020.

▪ The average individual order value (i.e., average purchase amount financed by a BNPL

loan) in 2021 was $135, up from $121 in 2020.

▪ 10.5 percent of borrowers were charged at least one late fee in 2021, up from 7.8 percent

in 2020.

▪ 13.7 percent of individual loans in 2021 had at least some portion of the order that was

returned, up from 12.2 percent in 2020.

▪ 3.8 percent of borrowers had a loan that was charged off in 2021, up from 2.9 percent in

2020.

4

The report identifies several competitive benefits of BNPL loans over legacy credit products.

These benefits are both financial (i.e., no interest and sometimes no late fees) and operational

(i.e., ubiquitous, easy to access, simple repayment structure).

The report also identifies several potential consumer risks, which fit into the three broad areas

of concern noted in the CFPB’s December 2021 market monitoring orders:

5

▪ Discrete consumer harms. The BNPL product is often structured in ways that may

present borrowers with undesirable operational hurdles, including the lack of clear

disclosures of loan terms, challenges in filing and resolving disputes, and a requirement

to use autopay for all loan payments.

▪ Data harvesting. Similar to many other large tech platforms, BNPL lenders often

collect consumer data—and deploy models, product features, and marketing campaigns

based on that data—to increase the likelihood of incremental sales and maximize the

lifetime value it can extract from each current, past, or potential borrower. These

practices (which may become even more prevalent and profitable as third-party data

tracking becomes more difficult on iOS

6

and Android

7

operating systems) may

4

Each lender has a slightly different definition of charge off, but at a high level this metric should be thought of as the

percent of borrowers who had a portion of their loan balance that was considered “uncollectable” after significant

time and collection efforts.

5

CFPB Opens Inquiry into ‘Buy Now, Pay Later’ Credit

6

National Public Radio, Apple Rolls Out Major New Privacy Protections For iPhones And iPads (April 26, 2021),

available at https://www.npr.org/2021/04/26/990943261/apple-rolls-out-major-new-privacy-protections-for-

iphones-and-ipads

7

Google, Introducing the Privacy Sandbox on Android (February 16, 2022), available at

https://blog.google/products/android/introducing-privacy-sandbox-android/

5

compromise consumers’ privacy and autonomy and contribute to the overextension risks

described below.

▪ Overextension. The BNPL business model may encourage overextension, and in doing

so present a pair of risks: loan stacking, which can cause borrowers to take out several

loans within a short time frame at simultaneous lenders; and sustained usage, in which

frequent BNPL consumption over a period of months and years may affect consumers’

ability to meet non-BNPL obligations.

6

2. Introduction

2.1 Product Definition

There is no single definition of “Buy Now, Pay Later” (BNPL). For purposes of this report, the

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) defines BNPL as the “pay-in-four” or “split pay”

product: a four-installment, no-interest consumer loan, typically with a down payment of 25

percent and the remaining three installments due in two-week intervals.

This report excludes other forms of short-term purchase financing, including:

▪ Point-of-Sale (POS) installment loans: A consumer installment loan tied to a

specific purchase, with monthly payments that may include interest or fixed finance

charges. Unlike the pay-in-four product, the POS installment loan is usually intended for

large, infrequent purchases (i.e., furniture and high-priced exercise equipment), with

term lengths up to three or four years. Down payments are typically not required.

▪ Post-purchase credit card installment plans: A product enhancement that many

credit card issuers have added in recent years that allows cardholders to repay a

previously purchased item on a payment plan in fixed monthly installments. While the

plan often includes amortized interest or fixed finance charges, it is separate from the

borrower’s credit card account balance and does not incur revolving interest.

2.2 Background

BNPL rose to prominence in the mid-2010s as an alternative form of short-term credit for

online retail purchases. Combining the digital point-of-purchase ubiquity of credit cards, the

simple repayment terms of traditional installment loans, and the general appeal of no interest

charges, BNPL was able to gain traction with consumers who enjoyed the ease of ecommerce

and the flexibility of being able to pay for goods and services over time but who may have been

leery of more traditional forms of debt.

Other similarities between BNPL and traditional credit cards include: a product that merges

payments and credit, an assigned credit amount that may replenish as the borrower makes

payments on outstanding loans, a business model that includes transaction fees charged to

merchants, and a high frequency of usage for retail purchases.

7

However, despite its rapid growth, the BNPL industry is less transparent than legacy credit

products, stemming from relatively sparse public data and the lack of BNPL loan repayment

furnishing to the Nationwide Consumer Reporting Companies (NCRCs).

In December 2021, the CFPB utilized section 1022(c)(4)(B)(ii) of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street

Reform and Consumer Protection Act

8

to issue market monitoring orders requesting data from

five of the firms that offer BNPL loans in the U.S.: Affirm, Afterpay, Klarna, PayPal, and Zip

(formerly Quadpay in the U.S.).

9

The orders consisted of a detailed set of qualitative and

quantitative questions designed to provide an in-depth view of the lenders’ U.S. BNPL-specific

businesses from 2019 through 2021.

10

Topics included loan volumes (split by merchant industry,

or vertical), revenue and expense figures, and strategies and policies on underwriting,

repayment, late fees, and product disputes.

11

The data and insights derived from these orders form the foundation of this report. The report is

supplemented by:

▪ Submissions to the CFPB via a BNPL-specific public request for comment that concluded

in March 2022,

12

along with depersonalized complaints filed with the CFPB’s Consumer

Complaint Database.

13

▪ Publicly available source materials, including financial filings, earnings calls, research

papers, and media interviews with BNPL lenders, vendors, and clients.

8

12 U.S.C. 5512.

9

CFPB Opens Inquiry into ‘Buy Now, Pay Later’ Credit. The CFPB has also published two blogs that alerted

consumers of the general risks of taking out a BNPL loan: https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/blog/should-

you-buy-now-and-pay-later/ and https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/blog/know-before-you-buy-now-pay-

later-this-holiday-season/

10

While some of the lenders surveyed have domestic non-BNPL business products and/or conduct business outside

of the United States, these market monitoring orders were confined to BNPL (i.e., “pay-in-four” only) in the US.

11

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Order to File Information (December 16, 2021), available at

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_bnpl_sample-order_2021-12.pdf

12

This public request for comment yielded 40 unique submissions: 13 were filed by consumer advocacy groups, and

12 were filed by trade associations (8 representing banks or credit unions, 2 representing retailers, and 2 representing

financial technology firms). The remaining 15 submissions were from private entities (8), governmental agencies (3),

academics (2), individuals (1), and an unknown (1) source.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Notice and Request for Comment Regarding the CFPB's Inquiry Into

Buy-Now-Pay-Later (BNPL) Providers (January 24, 2022), available at https://www.consumerfinance.gov/rules-

policy/notice-opportunities-comment/open-notices/notice-and-request-for-comment-regarding-cfpbs-inquiry-into-

bnpl-providers

13

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Consumer Complaint Database, available at

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints

8

While this report provides one of the most thorough quantitative and qualitative reviews of

BNPL in the U.S. to date, it has limitations.

First, there are limitations of scope. As described at the outset of this report, the CFPB limited

its review to the pay-in-four product. Within that product definition, this report is primarily

focused on “pure-players:” nonbank tech companies that offer BNPL, although they may also

offer other forms of point-of-sale lending.

Second, there are limitations of depth. The quantitative data received from the market

monitoring orders was provided in an aggregated (or “rolled up”) form rather than on an

individual loan level. As a result, the credit performance of individual borrowers across lenders

(i.e., those with concurrent BNPL loans from different lenders) or over time (either on their

BNPL products specifically or on their overall credit profiles, debt burdens, and savings levels)

cannot be assessed from the data collected. There is also no way to evaluate the structural

soundness of the lenders’ credit models. Lastly, the only available demographic that the lenders

collect and provided was age.

14

In addition, we cannot measure the impact of BNPL payments on

borrowers’ checking accounts, including non-sufficient funds or overdraft fees, or on borrowers’

capacity to repay other expenses or obligations.

Third, there are limitations of extrapolation. While, on a proportional basis, the data is likely

representative of the “pure-play” BNPL industry as a whole, the market monitoring orders only

covered the five lenders surveyed. As a result, the data cannot be used to definitively project the

overall size of the U.S. BNPL market. This report intentionally omits secondary-source market

sizings, as those are directional estimates from incomplete sources that often include POS loans

or other non-pay-in-four credit products.

2.3 Summary of Report and Findings

The body of the report is divided into three sections.

14

The lenders surveyed do not directly collect information on the racial and gender breakdown of their borrower

base, so the report does not include those demographics. However, a recent survey by the Federal Reserve Bank of

Philadelphia found a virtual 50-50 split between male and female users, and a 70-30 split between White and Non-

White users. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s most recent estimates, 75.8 percent of the overall population is

White.

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Buy Now, Pay Later: Survey Evidence of Consumer Adoption and

Attitudes (June 17, 2022), available at https://www.philadelphiafed.org/consumer-finance/consumer-credit/buy-

now-pay-later-survey-evidence-of-consumer-adoption-and-attitudes

United States Census Bureau, Quick Facts (July 1, 2021), available at

https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221

9

Section 3 (“Consumer Metrics”) explores BNPL from the perspective of the borrower, starting at

the point of “acquisition” (i.e., the initial interaction between potential borrower and BNPL

lender), continuing to the application and underwriting processes, and concluding with the

policies and procedures around account management and loan repayment.

Key findings in that section from the data collected from the market monitoring orders

include:

15

▪ 73 percent of applicants were approved for credit in 2021, up from 69 percent in 2020.

▪ The average individual order value (i.e., average purchase amount financed by a BNPL

loan) in 2021 was $135, up from $121 in 2020.

▪ 89 percent of loan repayments were made on a debit card in 2021, virtually unchanged

from each of the previous two years.

▪ 10.5 percent of borrowers were charged at least one late fee in 2021, up from 7.9 percent

in 2020.

▪ Lenders’ share of revenues from consumer fees (late fees and other fees) was 13.4

percent in 2021, up from 11.7 percent in 2020. Late fees specifically accounted for 6.9

percent of revenues in 2021 (up from 4.8 percent in 2020).

▪ 13.7 percent of individual loans in 2021 involved a purchase that was returned or

disputed, up from 12.2 percent in 2020.

▪ 3.8 percent of borrowers had a loan that was charged off in 2021,

16

up from 2.9 percent

in 2020.

Section 4 (“Market Metrics and Trends”) explores the BNPL industry from the perspective of the

lenders. The section is divided into three subsections covering top-line origination volumes, unit

margins (i.e., the variable revenues earned and expenses incurred on each loan originated), and

general business trends. Key findings from this section include the following:

15

Unless otherwise noted, all quantitative figures and metrics are derived solely from the responses from the five

lenders surveyed as part of the December 2021 market monitoring orders. All metrics cited from the market

monitoring orders are calculated as loan-level averages: loans are summed between the five lenders, not averaged

from the individual metrics of each lender.

16

Each lender has a slightly different definition of charge off, but at a high level this metric should be thought of as

the percent of borrowers who had a portion of their loan balance that was considered “uncollectable” after significant

time and collection efforts. There are accounting and tax impacts on lenders when a loan charges off and the specifics

of those impacts are out of scope of this report.

10

▪ The five lenders surveyed originated $24.2 billion in BNPL loans in 2021 (commonly

referred to as Gross Merchandise Volume, or GMV), nearly triple the $8.3 billion

originated in 2020 and more than twelve times the $2 billion originated in 2019.

▪ The Apparel and Beauty industries combined to make up 58.6 percent of originations in

2021, down from 69.9 percent in 2020 and 80.1 percent in 2019.

▪ BNPL usage for “everyday” or “necessity” purchases (gas, groceries, and utilities) was

$229.2 million in 2021 (0.9 percent of GMV), up 434 percent from $42.9 million in

2020, which itself was up 1,207 percent from $3.3 million in 2019.

▪ Unit margins (unit revenues less unit expenses) were 1.01 percent of GMV in 2021, down

from 1.27 percent in 2020. This reduction in margins stemmed from two sources: a

decrease in revenues from merchant discount fees (fees merchants paid to BNPL

lenders), and an increase in credit losses. An additional pressure point on lenders’ unit

margins arose in the first half of 2022: increasing funding costs, stemming from a

combination of idiosyncratic and macroeconomic conditions.

▪ In response to these pressures on unit margins, BNPL lenders have adjusted their

business models and strategies in a variety of ways, including tightening underwriting,

increasing their reliance on consumer fees (namely, late fees and other fees), and shifting

toward the app-driven “lead generation” acquisition model.

17

The latter adjustment has

the potential for the most far-reaching consumer impact, as it strengthens the breadth

and depth of the lender’s relationship with the borrower, and thus increases the

likelihood of habitual BNPL usage.

Section 5 (“BNPL and Consumer Financial Health”) explores the relationship between BNPL

usage and borrowers’ short- and long-term financial health. The section describes BNPL’s

benefits and risks as inextricably linked to the same “free and seamless” business model

employed by many of the Internet’s largest tech companies: an interest-free, accessible-at-you-

fingertips product that entices incremental spending. The financial and operational benefits

over legacy credit products are real and sizeable. Those same benefits, however, may lead to two

forms of borrower overextension: loan stacking (the risk of overconsumption from BNPL usage

at multiple concurrent lenders) and sustained usage (the risk of long-term BNPL usage causing

stress on borrowers’ ability to meet other, non-BNPL financial obligations).

17

As will be noted in that section, not every lender surveyed employed all three of these strategic adjustments.

11

Section 6 (“Takeaways and Risks”) concludes the report with takeaways from the prior sections

and an enumeration of BNPL’s largest consumer risks: discrete harms, data harvesting, and

overextension.

12

3. Consumer Metrics

3.1 Customer Acquisition

BNPL lenders implement two distinct strategies for acquiring their users. In the merchant

partner acquisition model, lenders sign contracts with specific online retailers to embed

their product on the retailers’ checkout pages. Consumers shopping on those retailers’ websites

and apps see the opportunity to split their purchase into four equal, interest-free installments—a

service provided by the BNPL lender.

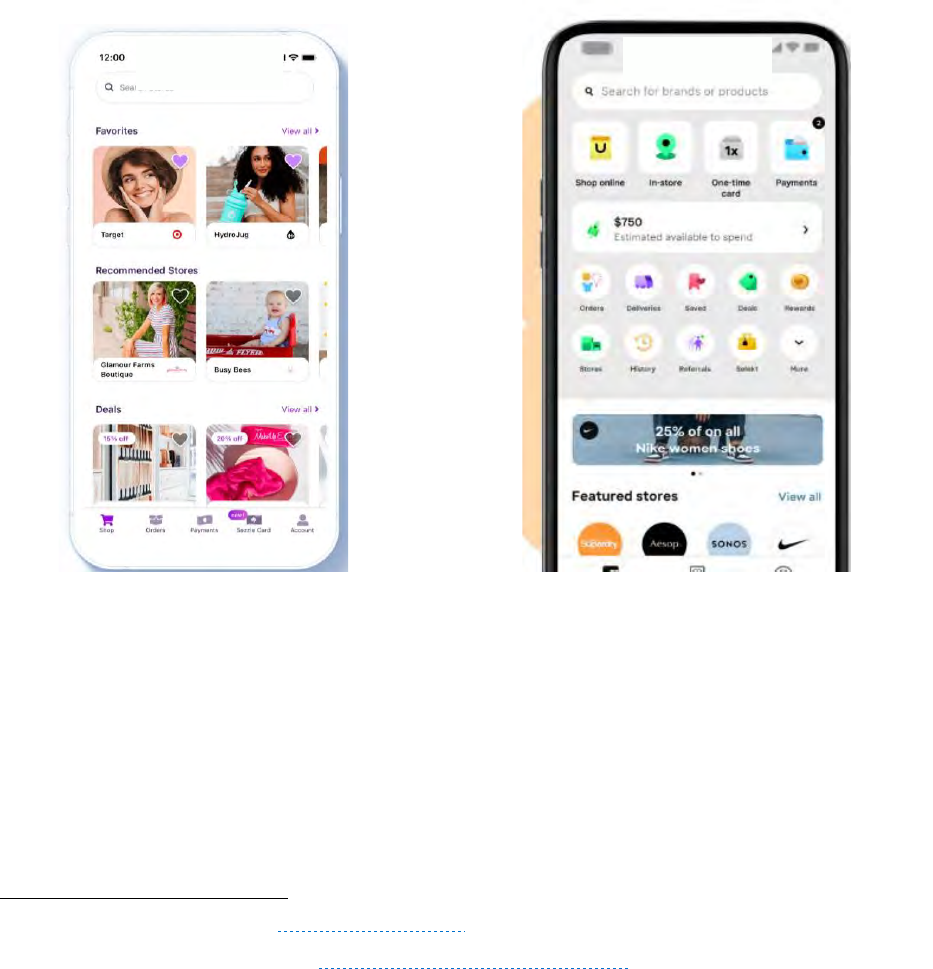

The images on the following page describe a typical BNPL merchant partner model checkout

flow.

18

In Image 3.1.1, a consumer shopping on a jewelry merchant’s product page is shown a

visual cue that BNPL financing is available for the particular item, with a link to a pop-up

message that provides more details (see Image 3.1.2). In Image 3.1.3, the consumer has reached

the point of checkout with that item in their cart and is presented with several payment options,

including the BNPL lender referenced in the prior two images. In Image 3.1.4, the consumer is

presented with the schedule of potential BNPL payments. If the consumer clicks “Place Order,”

they are taken to another screen to enter their personal information and payment details to

complete the application for credit, which doubles as the checkout page. If the consumer is

approved for credit and their down payment is processed, their BNPL loan begins.

18

Raven + Lily, Ellsworth Studs XL (2022), available at https://ravenandlily.com/products/ellsworth-studs-xl-brass

13

BNPL LENDER

Screenshots of the

merchant partner acquisition model, showing information on BNPL on the product detail pages

(

Images 3.1.1. and 3.1.2), and the availability of BNPL next to other payment options at the point of checkout (

Images

3.1.3 and 3.1.4

).

BNPL LENDER

BNPL LENDER

Image 3.1.1

Image 3.1.2

Image 3.1.3

Image 3.1.4

14

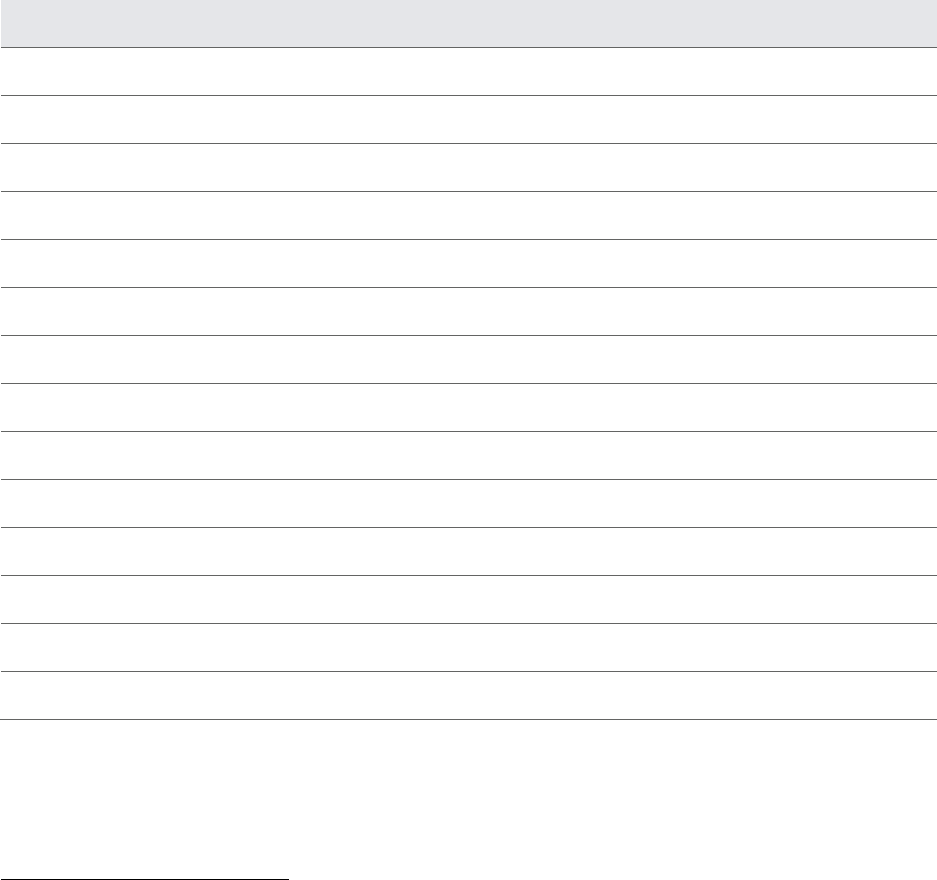

Image 3.1.6

Image 3.1.5

While BNPL lenders acquire the majority of their users via the merchant partner model

described above, many are rapidly shifting toward a model of direct consumer engagement. In

this app-driven acquisition model, consumers preemptively complete the credit application

process with the BNPL lender on its proprietary app. Once approved, consumers receive access

to a virtual shopping mall of merchants to patronize (see image 3.1.5 below),

19

along with a

purported credit amount provided by the lender (see the $750 “Estimated available to spend”

noted in Image 3.1.6 below, and a full explanation of the credit assignment strategy in Section

3.2.2).

20

Screenshots of the app-driven acquisition model, in which users directly interact with the BNPL lender via its

proprietary app. After earning credit approval, users are presented with a catalog of brands at which they can shop

and check out via BNPL (Image 3.1.5), along with a spending limit provided by the lender (see the $750 “Estimated

available to spend” in Image 3.1.6).

19

Sezzle, App (2022), available at https://sezzle.com/app

20

Klarna, Pay in 4 (2022), available at https://www.klarna.com/us/pay-in-4/

See Section 3.2 for a more detailed explanation of BNPL lenders’ credit assignment naming conventions, strategies,

and practices.

15

The underlying technology powering the app-driven acquisition model is a single-use, bank-

issued virtual card that an approved applicant uses to complete a BNPL loan.

21

The virtual card

technology provides BNPL lenders with two important benefits. First, it allows nearly any

merchant who engages in ecommerce to accept BNPL—even if the merchant has not signed a

specific contract with the BNPL lender.

22

This group of merchants are referred to as “non-

partnered merchants,” as they facilitate BNPL loans without a specific integrated partnership

with the lender who originated the BNPL loan. Second, it allows lenders to share in a portion of

the interchange fees that are collected from the virtual card transaction. This additional revenue

stream will be discussed more thoroughly in Section 4.

More generally, the app-driven model strengthens the consumer’s relationship with the BNPL

lender by driving the consumer to begin (and often end) their purchase journey within the

lender’s self-contained app ecosystem. This tightening of BNPL lenders’ brand awareness and

loyalty has several downstream impacts on lenders’ financial incentives and consumers’

interactions with the product, which are explored in further detail in Section 4.

3.2 Application Flow/Underwriting

3.2.1 Underwriting strategy

In the merchant partner acquisition model, the credit application typically occurs at the

merchant’s point of checkout—after the consumer has selected their item(s) to purchase. In the

app-driven acquisition model, consumers often begin the underwriting process immediately

upon logging into the BNPL app—before selecting their desired merchant or item(s).

In both acquisition models, the application process is seamless, streamlined, and brief to reduce

friction and shopping cart abandonment.

21

An unaffiliated bank issues the virtual card but the BNPL lender holds the balance sheet risk of the credit

transaction in the same manner that it does for a BNPL loan originated under the merchant partner model. The

relationship with the issuing bank is governed by the issuer processor, a tech platform who is responsible for the

front- and back-end code that generates the virtual card. The issuer processor coordinates the transaction and settles

the interchange fees amongst the four parties involved: the fintech client (in this case, the BNPL lender), issuing bank,

payment network, and issuer processor itself. An important technical feature of the virtual card is its flexibility: the

BNPL lender client can specify the time horizon, dollar amount, and merchants that are eligible for use. The

consumer is not responsible for any amount on the virtual card that remains unspent after it expires.

22

In fact, the merchant may not even know in advance if a customer is checking out with their own credit or debit

card or with a BNPL-issued single-use virtual card. In both cases, the user executes the transaction in the standard

credit card checkout flow, rather than in a checkout flow built especially for BNPL as is the case in the merchant

partner model.

16

The list of information required from the applicant is short. BNPL applicants are typically asked

for their name, address, phone number, email address and date of birth. Some lenders request

the last four digits of applicants’ Social Security Number (SSN).

Four of the five lenders surveyed use consumers’ credit profiles and credit scores, obtained from

one or more NCRCs, as part of their process of underwriting new and returning applicants.

23

Three of those four lenders rely on credit profile and/or score data as part of their general

underwriting strategy, while the fourth only uses it when an applicant has insufficient prior

history with the lender. For returning BNPL borrowers, all five lenders surveyed supplement the

credit approval decision with the applicants’ prior repayment history with that lender.

24

Lenders often use additional data sources and strategies to underwrite higher risk segments

(i.e., first-time applicants with low credit scores or scant credit history). At least one lender

requires some applicants to verify the funds in their checking account via third-party “open

banking” platforms, while at least one other lender requires some applicants to pay more than

the customary 25 percent down payment (thus reducing the amount of credit extended).

In the CFPB’s Request for Comments on BNPL, some commenters criticized the absence of

traditional “ability to pay” calculations from most BNPL lenders’ underwriting processes, in part

because that calculation should consider applicants’ other debt obligations in the context of their

income and assets and identify where an applicant may not have sufficient residual income to

make the BNPL payments.

25

In 2021, the credit approval rate across the five lenders surveyed was 73 percent, up from 69

percent in 2020 but in line with the 74 percent from 2019.

26

Table 1 on the following page depicts the credit approval rates across the five lenders surveyed

from 2019 through 2021, by age cohort. Over time, the approval rates have become more tightly

rank-ordered by cohort (i.e., older age cohorts tend to have higher approval rates).

23

The standard practice for the BNPL lenders who do obtain a credit report and/or score as part of its underwriting is

to receive this data via a “soft pull” that is not visible to other lenders and does not impact a consumer’s credit report

or scores. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, What's a credit inquiry? (September 4, 2020), available at

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/whats-a-credit-inquiry-en-1317

24

BNPL lenders who also offer non-BNPL products may incorporate payment history on those non-BNPL products

into their BNPL underwriting.

25

Comment from State Attorneys General of IL, CA, CO, CT, DE, HI (AG & OCP), IA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NV, NJ, NY,

NC, OR, PA, RI, VT, WA (March 25, 2022), available at https://www.regulations.gov/comment/CFPB-2022-0002-

0025

26

The term “approval rate” is defined the number of unique BNPL users approved for credit divided by the sum of the

unique borrowers and unique applicants declined for credit in the given time period studied.

17

TABLE 1: CREDIT APPROVAL RATE BY AGE COHORT, 2019-2021

Age Cohort

2019

2020

2021

18-24

73%

67%

69%

25-33

72%

68%

72%

34-40

73%

68%

73%

41-50

76%

71%

75%

51-64

79%

74%

77%

65+

74%

72%

76%

Figure 1 shows the share of unique BNPL borrowers by age cohort for 2019, 2020, and 2021.

FIGURE 1: SHARE OF UNIQUE BNPL BORROWERS BY AGE COHORT, 2019-2021

21.4%

18.8%

16.8%

35.9%

34.5%

32.6%

17.7%

18.8%

19.2%

15.6%

17.0%

18.2%

8.1%

9.3%

11.0%

1.2% 1.6% 2.1%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2019 2020 2021

18-24 25-33 34-40 41-50 51-64 65+

In each of the three years surveyed, approximately half of the borrower base was 33 years old or

younger. The youngest cohort (ages 18—24) accounted for 16.8 percent of the borrower base in

2021, down from 18.8 percent in 2020 and 21.4 percent in 2019. In 2021, among the five lenders

surveyed, the 18-24 cohort’s share of the overall borrower base ranged from 12.1 percent to 19

percent.

18

Figure 2 below juxtaposes each age cohort’s share of the 18+ US population

27

(left bar) against

its share of the 2021 BNPL borrower base (right bar), with the middle numbers inside the

arrows representing the “index ratio:” the degree to which each cohort’s presence in BNPL is

over- or under-indexed relative to its share of the general population.

FIGURE 2: SHARE OF UNIQUE BNPL BORROWERS BY AGE COHORT (2021) VS OVERALL 18+ US RESIDENT

POPULATION (CENSUS BUREAU, AS OF 12/2020)

11.7%

16.8%

16.2%

32.6%

11.9%

19.2%

15.6%

18.2%

22.7%

11.0%

22.0%

2.1%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Overall US (12/2020) BNPL (2021)

18-24 25-33 34-40 41-50 51-64 65+

1.44x

2.02x

1.61x

1.17x

0.48x

0.10x

(Source: U.S. Census Bureau and market monitoring data)

In general, younger cohorts are more over-indexed in their BNPL usage than older cohorts,

though the rank-ordering ends at the youngest age cohort. The 18—24 cohort has an index ratio

of 1.44 (meaning that members of that cohort’s representation in BNPL is 1.44 times as high as

its representation in the overall population), which trails both the 25—33 (2.02) and 34—40

(1.61) cohorts. On the other end of the spectrum, the 65+ cohort’s index ratio of 0.1 (it

represents 22 percent of the overall population versus 2.1 percent of the BNPL borrower base)

makes it the most underrepresented age group.

27

United States Census Bureau, National Population by Characteristics: 2010-2019, “Monthly Postcensal Resident

Population, 7/1/2020 to 12/1/2020” (February 16, 2022), available at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-

series/demo/popest/2010s-national-detail.html

19

3.2.2 Credit assignment strategy

BNPL lenders’ underwriting models work in concert with their strategies on how much credit to

extend to each approved applicant. Many lenders employ a “low-and-grow” strategy: extending

limited credit to first-time borrowers, and gradually raising the amount of credit extended as the

borrower exhibits positive repayment behavior.

While a general low-and-grow strategy is commonplace in the BNPL industry, the exact amount

assigned to first-time borrowers is not. One lender, for example, caps its credit extension to

first-time borrowers at $600 (though in practice it may set lower amounts for many first-time

borrowers). Another lender has caps for first-time borrowers that range from $100 to $1,000,

depending on various risk factors. Some BNPL lenders also restrict the number of concurrent

loans a borrower may have outstanding, though that is also not uniform across the industry.

Historically, consumers interacting with BNPL lenders via the merchant partner acquisition

model did not see their credit assignment amount separate from the present transaction. Since

the original iterations of BNPL were executed at checkout, the credit assignment process was

often interwoven with the ultimate approval/decline decision for the specific purchase in

question.

The app-driven acquisition model has made the amount of available credit for which a consumer

is qualified much more explicit. Upon logging into the app, users are often guided to

immediately apply for credit (before they have selected a purchase). Approved users are then

typically presented with a purported available credit amount, sometimes referred to as

“purchase power,”

28

“pre-approved to spend,”

29

“estimated spending power,”

30

or “prequalified

to spend.”

31

The approved amount is usually considered a placeholder until the user actually attempts to take

a BNPL loan, at which point they are re-underwritten. All four of the lenders surveyed who have

28

Klarna, How much am I eligible to spend? (2022), available at https://www.klarna.com/us/customer-

service/how-much-am-i-eligible-to-spend. Also see Klarna mobile application.

29

Afterpay, Financial Wellness (2022), available at https://www.afterpay.com/en-US/financial-wellness. Also see

Afterpay mobile application.

30

Zip, How much can I spend using the Zip app? (2022), available at https://help.us.zip.co/hc/en-

us/articles/4402386078619--How-much-can-I-spend-using-the-Zip-app. Also see Zip mobile application.

31

Affirm, About prequalifying (2022), available at https://helpcenter.affirm.com/s/article/about-prequalifying.

Also see Affirm mobile application.

20

proprietary apps have text that accompanies the “information” icon next to a user’s available

credit that describes it as “estimated” and not guaranteed.

32

Through CFPB complaints, some consumers reported that BNPL lenders lack transparency

regarding credit assignment. Some consumers complained about arbitrary decreases, rendering

them unable to use the product or make otherwise planned purchases: “I've been having an

account with [BNPL lender] for 2+ years and this is the 2nd time they dropped my limit and

changed my status for no reason.”

33

Other consumers have noted that their available credit, as displayed, may not reflect the user’s

actual purchasing power at a given lender. As one user noted, “consistently [BNPL lender] tells

its users that they have about $1300.00 in credit but only ever allows it to spend just under

$300.00 over time no matter whether one has excellent payment history, pays early, has

excellent credit rating… the policy is not clear.”

34

These declines may inhibit the consumer’s

ability to effectively plan for certain purchases and affect their relationships with lenders and

merchants.

3.2.3 Fraud and age screening

BNPL lenders use additional forms of screening to address potential fraud and to ensure that

potential borrowers meet applicable state minimum age requirements.

35

Fraud screening consists of a combination of first- and third-party data sources designed to

detect users with no intent to repay. As is the case with other forms of lending, many of the data

sources used in BNPL lenders’ fraud screening involve various forms of Personally Identifiable

Information (PII) meant to identify individuals associated with previous fraudulent behavior.

All five of the lenders surveyed require applicants to enter their date of birth as part of the BNPL

application and will decline credit to any applicant whose birthdate does not meet minimum age

requirements. Three of the five lenders also use a third-party vendor to validate the applicant’s

submitted birthdate by matching to other elements from the application (such as name, address,

32

Affirm, Afterpay, Klarna, and Zip apps; also noted in the previously cited pages of the lenders’ websites.

33

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Consumer Complaint 4813400 (October 15, 2021), available at

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/4813400

34

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Consumer Complaint 4732609 (September 18, 2021), available at

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/4732609

35

All five lenders surveyed have a global minimum age policy of 18 years.

21

phone, and email). Lenders often employ this additional verification step to ensure proper

product usage and to mitigate various forms of fraud.

3.3 Account Management/Repayment

3.3.1 Payment method selection, change, and removal

As discussed above, BNPL lenders typically require borrowers to pay a share of the purchase

price (usually 25 percent) as a down payment at checkout. Four of the five lenders surveyed

require borrowers to use their existing debit or credit card for the down payment. This practice

serves two main purposes. First, debit and credit card networks provide instantaneous

verification that the applicant has sufficient checking account funds (debit card) or available

credit (credit card) to cover the down payment, which effectively guarantees that the first

installment will be paid. Second, lenders are able to automatically debit the same card for the

three subsequent installments. As will be discussed in subsequent sections, this commonly

adopted “mandatory autopay” practice may present risks to borrowers.

Table 2 below shows the share of all individual BNPL installment payments by payment method.

TABLE 2: SHARE OF BNPL INSTALLMENT PAYMENTS BY PAYMENT METHOD, 2019-2021

Payment Method

2019

2020

2021

Debit card

86.8%

88.5%

89.0%

Credit card

12.5%

11.0%

10.1%

ACH

0.3%

0.2%

0.6%

Prepaid card

0.3%

0.3%

0.3%

Check

< 0.1%

< 0.1%

< 0.1%

Debit card is the overwhelming payment method of choice, with an 89 percent share of all

payments made in 2021. Between the five lenders surveyed, debit’s share ranged from 74

percent to 92 percent, and credit’s share ranged from 8 to 21 percent. Debit and credit cards

combined account for over 99 percent of all payments in each of the three years surveyed.

22

Consumer advocates have critiqued BNPL lenders for permitting payments via credit card,

effectively allowing borrowers to pay for credit with credit.

36

The two most common risks cited

are “hidden interest” (i.e., that borrowers will end up paying interest on BNPL purchases if they

use a credit card on which they revolve, or do not pay the balance in full) and general concerns

of overextension from shifting debt between credit products.

All five lenders surveyed allow borrowers to change their payment method for the second

through fourth installments. Some lenders have payment change options on their online portals

in addition to Interactive Voice Recognition and traditional phone channels. Depending on the

lender and contact channel, borrowers may be able to make subsequent payments via

Automated Clearing House (ACH, i.e., direct bank transfer), prepaid card, or check.

BNPL lenders have different operational policies concerning payment method removal (i.e.,

removing autopay without adding a new payment method). One lender allows borrowers to do

so on its self-service online portal. A second lender allows borrowers to do so by contacting

customer service electronically or by phone, and a third allows it via phone-based customer

service only. Two other lenders generally prohibit the practice, meaning that borrowers cannot

turn autopay “off.”

37

By implementing these policies, lenders can benefit from increased payment “stickiness” to keep

credit losses below a desired threshold, which may allow lenders to be less stringent in their

underwriting and credit assignment strategies. However, from the borrower’s perspective,

forced autopay may have the effect of depriving those borrowers of a degree of agency. A

borrower facing multiple concurrent debts and bills may prefer to prioritize other obligations

over their BNPL loan, and policies that limit that ability can be harmful to the borrower’s

financial well-being. Likewise, not allowing borrowers to easily remove their payment method

could inadvertently lead to overdraft.

3.3.2 Late fees

Three of the five lenders surveyed charge late fees for missed payments, typically the minimum

of a flat fee or a percentage of the missed payment. One lender previously charged late fees but

ended that practice in Q4 2021. One of the lenders that currently charges late fees does not limit

36

As one response to the CFPB’s public request for comment argued, “For those with revolving credit outstanding on

their cards, BNPL charges will begin to accrue interest from the day they post, and the so-called ‘free’ BNPL loan will

not, in fact, be free.”

Comment from Center for Responsible Lending (March 25, 2022), available at

https://www.regulations.gov/comment/CFPB-2022-0002-0028

37

One of those two lenders allows customer service associates to remove autopay in “certain cases,” but did not

provide additional context on the frequency of or situations leading to these cases.

23

late fee amounts on either a per-installment or per-loan basis, except in two states where a limit

is required by law. Depending on the borrower’s state of residence, late fees may vary.

38

Of the three lenders who charge late fees, two have a policy to charge a late fee at 10 days past

due (DPD), while the other lender may charge the fee after one DPD. In the past, several lenders

have reserved the ability to charge multiple late fees for a single missed installment, and one

lender outside the scope of the inquiry may currently charge two late fees after a missed

payment.

39

Some lenders also cap late fees based on the order amount or the amount of the

missed payment.

Table 3 below summarizes the policies of the lenders that may charge late fees.

TABLE 3: LATE FEE POLICIES, 2019-2021

2019

2020

2021

Amount

Frequency

Amount

Frequency

Amount

Frequency

Lender 1

$8

Twice per

missed

payment

$8

(capped)

Once per

missed

payment

$8

(capped)

Once per

missed

payment

Lender 2

$10

(capped)

Once per

missed

payment

$7

Once per

missed

payment

$7

(capped)

Once per

missed

payment

Lender 3

$7

Twice per

missed

payment

$7

Once per

missed

payment

$7

Once per

missed

payment

As shown in Table 4 on the following page, 10.5 percent of borrowers were charged at least one

late fee in 2021, while 6.7 percent of loans incurred at least one late fee.

38

While some states consider BNPL to be consumer credit and require state licensing or registration, as well as

compliance with state consumer credit laws, other state laws do not require licensing or registration for BNPL

products with no interest or finance charges. All five of the BNPL lenders surveyed as part of the CFPB’s December

2021 market monitoring orders (Affirm, Afterpay, Klarna, PayPal, and Zip) are currently licensed or registered in

several states under consumer credit regulations, although at least one BNPL lender now partners with a bank to

issue some of its BNPL loans.

39

Four, User Agreement (2022), available at https://www.paywithfour.com/legal/user-agreement

24

TABLE 4: LATE FEE METRICS, 2019-2021

2019

2020

2021

Borrower-level late

fee rate

40

8.5%

7.9%

10.5%

Loan-level late fee

rate

41

5.7%

4.8%

6.7%

Late fees collected

as a share of GMV

0.31%

0.20%

0.28%

Limiting the assessment to lenders that charge late fees, approximately 12 percent of borrowers

were charged at least one late fee in 2021 and 7 percent of loans incurred at least one late fee.

While the total amount of late fees charged increased nearly tenfold from 2019 to 2021, this was

accompanied by a commensurate increase in loan origination volume.

On a normalized basis, late fees charged decreased from 2019 to 2020, but experienced an

uptick from 2020 to 2021. Several lenders changed their practices in this period, with one entity

dropping late fees. Two lenders introduced late fee caps on either a per-installment or per-loan

basis, while another eliminated an “arrears fee” charged in addition to standard late fees.

However, it is unclear whether the relative decrease in late fees from 2019 to 2020 is due to

policy changes or volatile macroeconomic conditions brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Several lenders also waive certain late fees on borrower request or a showing of hardship, and

not all late fees charged are collected. In 2021, 57 percent of all late fees charged were collected

by the lenders.

Late fees in the BNPL should be considered in the context of a product for which virtually all

borrowers are on autopay. As a result, the assessment of a late fee suggests that a borrower’s

checking account lacked sufficient funds for the BNPL payment to be successful.

3.3.3 Returns/Disputes

When a borrower wishes to return or dispute a product purchased using a BNPL loan, all five

lenders instruct the borrower to contact the merchant that sold the product. If the merchant

processes the return, the funds will be credited to the borrower after a processing delay. Due in

part to the common use of BNPL in the apparel and fashion industries, returns are a relatively

40

Defined as the number of unique borrowers charged one or more late fees divided by the total number of

borrowers.

41

Defined as the number of loans with one or more late fees divided by the total number of loans.

25

frequent occurrence among the five lenders. As seen in Table 5 below, 13.7 percent of loans

involved a return or dispute in 2021, and on a dollar basis, 60.3 percent of these returns or

disputes were refunded.

TABLE 5: RETURN AND DISPUTE METRICS, 2019-2021

2019

2020

2021

Dollar amount of returns/disputes

($ millions)

227

680

1,807

Dollar amount of refunds ($ millions)

102

368

1,089

Dollar refund rate

42

45.1%

54.1%

60.3%

Loan return/dispute rate

43

14.8%

12.2%

13.7%

Dollar return/dispute rate

44

5.0%

4.4%

4.5%

The return process may be complicated when the merchant declines to authorize a refund for a

disputed item. In these cases, a borrower may contact the BNPL lender to file a dispute, either

via the lender’s app or by contacting customer support. The BNPL lender then generally begins

an investigation and contacts both the borrower and merchant. Once the investigation is

concluded, the lender assigns responsibility to one party and may issue a refund or credit.

However, with the short-term, six-week nature of BNPL loans, a successful merchant dispute

may not be resolved during the loan term. In these instances, the borrower may be required to

make additional payments under the loan contract until the investigation is concluded.

In the event of a non-partnered loan facilitated by a virtual card, dispute resolution is

complicated by the involvement of issuer processors that are responsible for generating the

single-use cards. Disputes initiated by the borrower through the BNPL lender are mediated

through the issuer processor before reaching the merchant. Likewise, a return or refund

initiated by the merchant must go through the issuer processor before reaching the BNPL

lender. Since the merchant is unable to distinguish a BNPL single-use card from other card

transactions, the merchant may be unaware of the BNPL lender’s role, creating potential

communication lapses and leaving borrowers responsible for ongoing payments during these

42

Defined as the dollar amount of loans refunded as a share of the dollar amount of loans returned or disputed.

43

Defined as the number of loans involving a return or dispute divided by the total number of loans originated in a

given year.

44

Defined as the dollar amount of loans returned or disputed as a share of gross merchandise volume.

26

lapses. As one borrower who experienced issues with a virtual card transaction noted in a CFPB

complaint narrative, “I called [merchant] and they had no idea who [BNPL lender] was… [BNPL

lender] and [merchant] are pointing fingers at each other and I am left holding the bag.”

45

Consumer complaints to the CFPB indicate that returns and disputes are a common concern.

46

In some instances, consumers have reported difficulties in informing the BNPL lender that they

are disputing a purchase, concerns with continued payment on a disputed item, and a general

opacity in the dispute process.

47

In response to these complaints, BNPL lenders gave varied

answers. They sometimes offered consumers a refund, and in other instances stated they were

unable to assist for various reasons such as lack of action on a consumer’s part. For example,

one consumer stated in their complaint:

[BNPL lender] refuses to acknowledge and follow its own published dispute policies. I

have had 2 recent issues with merchants where they clearly violated the merchant

guidelines published on [BNPL lender’s] website resulting in a case that clearly

qualified for a dispute. In both instances, the company completely refused to even open

a dispute and investigate the now fraudulent charges... Screenshots of all conversations

with the merchant were submitted to [BNPL lender] and they refused to investigate the

dispute.

48

In its response, the company stated it was unable to help the consumer obtain a refund because

the consumer had not adequately attempted to obtain a refund from the merchant first.

One lender surveyed requires continued payments pending a dispute, two lenders allow

borrowers to defer payment for a short time following a reported dispute, and two lenders stop

payment indefinitely during a reported dispute. The ease of reporting a dispute also varies from

45

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Consumer Complaint 4296099 (April 14, 2021), available at

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/4296099

46

This analysis was based on a review of consumer complaints about BNPL loans received by the Bureau between

Jan. 1, 2021 and Mar. 31, 2022. Other common topics included issues with debt collection. For example, consumers

complained that the BNPL credit was applied for fraudulently by someone else. Consumers also sometimes

complained that their accounts were sent to collection for items they had returned, or that they were being contacted

by collection agencies about debts that they had already paid.

47

See, e.g., Consumer Complaint 5221297, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-

research/consumercomplaints/search/detail/5221297 (consumer’s original item was stolen in transit and the second

arrived damaged by which point the BNPL lender’s deadline for a refund had passed); Consumer Complaint 5359461,

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumercomplaints/search/detail/5359461 (consumer

complained about confusion and delays in refund for defective merchandise).

48

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Consumer Complaint 4288475 (April 11, 2021), available at

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/4288475

27

lender to lender and may contribute to borrower frustration. Though not all lenders provided

the information, most of them require that borrowers submit disputes in 60 or 120 days.

3.3.4 Other fees

In addition to late fees, two lenders either currently charge or recently charged other consumer

fees. One lender charged a non-sufficient funds (NSF) fee of $25 (lowered to $10 or installment

amount, whichever was lower, in Q4 2021) for ACH payments that failed to clear, resulting in a

chargeback. Due to the low volume of payments made via ACH, the cumulative amount of NSF

fees collected in all three years covered by the CFPB’s market monitoring orders was

approximately $640,000. In 2021, the amount of NSF fees charged amounted to less than one

percent of late fees in the same year. The lender stopped charging NSF fees in Q4 2021.

Another lender charges a fee on virtual-card-facilitated loans made with non-partnered

merchants, amounting to $1 per installment payment (i.e. $4 per loan). In addition, a lender

outside the scope of the CFPB’s market monitoring orders charges a service fee of $0.25 per

installment payment (i.e. $1 per loan).

49

3.3.5 Failed Payments, Re-presentments, and Charge-offs

On occasion, payments made by borrowers to BNPL lenders fail due to insufficient funds or

credit associated with the borrower’s payment method. As shown in Table 6 below, in 2021, 4.1

percent of all loans experienced one or more declined or failed payment, and 7.5 percent of all

borrowers experienced a failed or declined payment. Mirroring late fee trends, declined or failed

payments decreased slightly from 2019 to 2020 but increased from 2020 to 2021.

TABLE 6: DECLINED OR FAILED PAYMENT METRICS, 2019-2021

2019

2020

2021

Loan-level payment

failure/decline rate

50

2.6%

2.4%

4.1%

Borrower-level payment

failure/decline rate

51

3.9%

4.3%

7.5%

49

nate, nate pay later terms and conditions (2022), available at https://www.nate.tech/paylater-terms

50

Defined as the number of loans with one or more failed or declined payments as a share of total loans originated.

51

Defined as the number of borrowers who had at least one payment fail or declined divided by the total number of

borrowers.

28

In the event of a failed or declined payment, all five lenders allow for additional re-presentments

(i.e., attempts to reauthorize) the payment at least one additional time, with one lender allowing

for eight potential re-presentments. On average, the lenders surveyed will attempt to re-present

as soon as 1 DPD and every one to four days from the previous failed re-presentment attempt.

The final stage of a loan’s delinquency is charge off, a designation that a lender assigns to

severely delinquent debt on which it has a very low expectation of collecting. The five lenders

assign a charged off status at different levels of a loan’s delinquency, ranging from 84 to 180

days past due.

Table 7 below details the aggregated loan charge off rate (i.e., the number of charged off loans as

a portion of all originated loans) and unique borrower charge off rate (i.e., the number of unique

borrowers with at least one charged off loan as a portion of all unique borrowers) for 2019

through 2021.

TABLE 7: AGGREGATED LOAN AND UNIQUE BORROWER CHARGE OFF RATES, 2019-2021

Metric

2019

2020

2021

Loan charge off rate

2.59%

1.83%

2.39%

Unique borrower charge off rate

3.54%

2.93%

3.79%

The decrease in charge off rates in 2020 was consistent with metrics seen across consumer

lending industries, as Covid-19-induced behavioral changes and government stimulus payments

temporarily bolstered consumer savings.

52

The report will delve into the 2021 increase in charge

off rates in Section 4, which details lenders’ responses to shocks to their unit margins.

Commenters have noted concerns about potential adverse impacts of BNPL loan delinquencies

on younger borrowers and other demographic groups. One submission to the CFPB’s public

request for comment stated that “[y]ounger, lower-income and less financially-sophisticated

consumers are at grave risk of being targeted to buy more and accumulate debt that they cannot

afford.”

53

52

Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Study shows surge in savings during the pandemic (April 29, 2021),

available at https://www.kansascityfed.org/ten/2021-spring-ten-magazine/study-shows-surge-in-savings-during-

the-pandemic

53

Comment from Center for Responsible Lending (March 25, 2022), available at

https://www.regulations.gov/comment/CFPB-2022-0002-0028

29

Figure 3 below shows the share of unique borrowers with one or more loan in derogatory status,

cut by age cohort.

54

FIGURE 3: SHARE OF UNIQUE BNPL BORROWERS BY AGE COHORT WITH 1+ DEFAULT OR CHARGE-OFF

5.3%

4.9%

4.5%

3.5%

2.8%

4.1%

5.2%

3.9%

3.1%

2.4%

2.1%

3.1%

5.7%

4.8%

3.8%

2.9%

2.3%

3.1%

0.0%

1.0%

2.0%

3.0%

4.0%

5.0%

6.0%

18-24 25-33 34-40 41-50 51-64 65+

2019 2020 2021

With the exception of the oldest cohort, credit performance rank-ordered by age: the younger

the age cohort, the higher the share of borrowers with loans in derogatory status. This pattern

held for each of the three years surveyed and is consistent with the rank-ordering of credit card

delinquencies by age cohort reported in the New York Federal Reserve Bank’s quarterly

Household Debt and Credit report.

55

Each age cohort experienced an increase in the share of unique borrowers with loans in

derogatory status from 2020 to 2021, mirroring macroeconomic trends that are discussed in

further detail in Section 4. The youngest age cohort (18—24) was the only one to record a higher

derogatory rate in 2021 (5.7 percent) than in 2019 (5.2 percent).

54

Derogatory is defined as a loan that meets either of the following two conditions: in default (default defined as the

failure of a consumer to repay their obligation), or sent to a third-party debt collector.

55

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit: 2022 Q1 (May 2022),

available at https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/hhdc_2022q1.pdf

30

3.3.6 Collections

All five of the lenders surveyed have, at least some point between 2019 and 2021, used third-

party debt collectors to collect delinquent loan balances. Two of the lenders only used debt

collectors for specific, short intervals, while the other three use debt collectors as part of their

general collections strategy. One common industry practice is to refer loans to debt collectors

after the loans have reached charged off status, and any payments made via debt collectors are

usually counted in the lender’s income statement as “recoveries.”

The third-party debt collector establishes a new relationship with the borrower. As a general

practice, given the low-dollar, digital-first nature of the product, debt collectors collecting BNPL

loans rely more heavily on digital communications channels (text and email) than on traditional

channels such as phone calls and paper mail.

Throughout the three years surveyed, all of the agreements between BNPL lenders and debt

collectors were on a contingency placement basis (i.e., the debt collector earns a commission on

all debts collected, but the debts remain on the balance sheet of the BNPL lender) rather than

sold to a third-party debt buyer.

31

4. Market Metrics and Trends

4.1 Volume and Usage

Table 8 below shows the aggregated loan and dollar origination figures from the five lenders

surveyed from 2019 through 2021, along with the 2019-to-2021 compound annualized growth

rate (CAGR).

56

TABLE 8: BNPL LOAN ORIGINATION VOLUME AND AVERAGE LOAN SIZE, 2019-2021

2019

2020

2021

19-21

CAGR

Loan Originations (Millions)

16.8

68.4

180.0

227%

Dollar Originations

57

($ Billions)

2.0

8.3

24.2

245%

Average Loan Size

(Dollar Originations /

Loan Originations)

$121

$121

$135

5.5%

In 2021, the five lenders originated 180 million BNPL loans totaling $24.2 billion,

58

for an

average loan size (often referred to as average order value) of $135. Both loan and dollar

originations are growing at over 200 percent per year since 2019, with the latter’s growth

slightly outpacing the former.

The largest of the five lenders surveyed accounted for 39 percent of GMV in 2021, and the

smallest accounted for 6 percent. In 2020, the largest lender offering BNPL loans accounted for

57 percent of overall GMV; in 2019, the largest lender accounted for 71 percent.

Figure 4 on the following page shows the trend of loan and dollar originations by quarter.

56

CAGR can be thought of as the average year-over-year rate of growth for a given metric. For example, the 245

percent CAGR for unit originations means that, over the two year-over-year periods studied (2019 to 2020 and 2020

to 2021), unit originations grew by an average of 245 percent per year. Its main analytical benefit is to create a

standardized figure that can compare growth over different lengths of time.

57

Also referred to as Gross Merchandise Volume, or GMV.

58

This dollar originations (or GMV) figure includes the overall checkout amount of each loan, inclusive of the 25%

down payment. For example, a $100 purchase that is financed via BNPL will require $25 paid at checkout and $75

paid in three subsequent installments. The GMV from that purchase is $100.

32

FIGURE 4: BNPL LOAN ORIGINATION VOLUME BY QUARTER, 2019-2021

1.7

2.6

4.1

8.4

8.6

12.7

15.1

32.0

34.2

39.4

43.3

63.1

0.2

0.3

0.5

1.0

1.0

1.5

1.8

4.0

4.4

5.2

5.9

8.7

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Dollar Originaiton Volume ($ Billions)

Loan Origination Volume (Millions)

Loan Originations (Millions, left axis) Dollar Originations ($ Billions, right axis)

Not surprisingly, the two metrics have moved together, with near-identical quarter-over-quarter

growth rates. The largest deviation between the two came between Q4 ’20 and Q2 ’21, when

GMV growth slightly outpaced loan growth (evidenced by the increase in average loan size in

2021). The fourth quarter (i.e., the holiday shopping season) registered the highest quarter-

over-quarter growth in each of the three years surveyed.

As discussed in other sections in this report, repeat usage is a key metric for BNPL lenders’ top

and bottom lines. Figure 5 on the following page shows the number of loans originated per

unique borrower by quarter (or “usage rate”).

33

FIGURE 5: BNPL QUARTERLY USAGE RATE, 2019-2021

1.9

2.0

2.0

2.1

2.1

2.4

2.4

2.5

2.6

2.6

2.5

2.8

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

2019Q1 2019Q2 2019Q3 2019Q4 2020Q1 2020Q2 2020Q3 2020Q4 2021Q1 2021Q2 2021Q3 2021Q4

These figures are aggregated across the five lenders surveyed, but only for loans on each lender’s

balance sheet. In other words, a usage rate of 2.5 means that the average BNPL borrower used

the product 2.5 times in a quarter at a given lender; this data cannot be used to measure the

number of loans that same borrower may have taken across different BNPL lenders. Due to the

fact that the data was presented in terms of unique borrowers per quarter, it is not possible to

infer the number of times the average borrower uses BNPL throughout the course of a year.

59

The quarterly usage rate has steadily increased over the past three years, reaching a high of 2.8

loans per unique borrower in Q4 ’21. In Q4 ’21, four of the five lenders surveyed had a usage rate

between 2.9 and 3.2 per quarter, while the fifth had a usage rate below 2.

While these metrics represent the average usage across the BNPL customer base, the increase in

repeat usage has accelerated faster at the upper ends of the spectrum. Figure 6 on the following

page shows the share of unique quarterly borrowers with at least five and at least ten BNPL

loans in that quarter.

59

For example: of the 13.3 million unique borrowers across the five lenders surveyed in Q1 ’21, some unknown

number also used the product in Q2, Q3 and Q4 ’21. Thus, one cannot sum the unique borrower totals from separate

quarters, as that would entail an unknown amount of double counting.

34

FIGURE 6: SHARE OF UNIQUE QUARTERLY BNPL BORROWERS WITH 5+ AND 10+ LOANS, 2019-2021

1.1%

1.3%

1.4%

1.6%

1.7%

2.5%

2.6%

3.0%

3.2%

3.2%

3.1%

4.0%

6.3%

7.3%

7.3%

8.1%

8.9%

12.0%

11.9%

12.9%

13.5%

13.5%

12.9%

15.5%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

2019Q1 2019Q2 2019Q3 2019Q4 2020Q1 2020Q2 2020Q3 2020Q4 2021Q1 2021Q2 2021Q3 2021Q4

Share of Unique Quarterly BNPL Borrowers

10+ BNPL Loans 5+ BNPL Loans

In Q4 ’21, 15.5 percent of unique borrowers took out five or more BNPL loans, a 144 percent

increase from Q1 ’19 and a 20 percent increase from Q4 ’20. On a normalized basis, the growth

figures are even more pronounced for the share of borrowers who took out ten or more BNPL

loans, with a 251 percent increase from Q1 ’19 to Q4 ’21 (1.1 to 4.0 percent) and a 34 percent

increase from Q4 ’20 to Q4 ’21 (3.0 to 4.0 percent).

BNPL lenders segment their loan volume by merchant vertical (i.e., retail industry).

60

Table 9 on

the following page shows the GMV (i.e., dollar originations) by vertical and year across the five

lenders surveyed, expressed as raw dollar amounts and as a share of the year’s total.

60

The CFPB received loan vertical information from all five lenders per each lender’s naming conventions. As a

result, the CFPB standardized the data and matched each lender-provided vertical name with uniform subvertical and

vertical names. See Appendix Section 7.1 for the full list. BNPL lenders are also able to prohibit consumers from using

BNPL for specific excluded products. The list of these excluded products usually includes illegal items such as

narcotics and drug paraphernalia, gambling, and cash-equivalent items with high fraud risk (gift cards, money

transfers, cryptocurrencies, etc.). Many lenders also exclude weapons, including firearms, though this exclusion is not

universal across the BNPL industry. See New York Times, ‘Buy Now, Pay Later’ Becomes a New Way to Pay for Guns

(June 24, 2022), available at https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/24/business/buy-now-pay-later-guns.html

35

TABLE 9: GMV ($ BILLIONS) AND PERCENT OF TOTAL BY MERCHANT VERTICAL, 2019-2021

2019

2020

2021

Vertical

GMV ($B)

% of

Total

GMV ($B)

% of

Total

GMV ($B)

% of

Total

Apparel

1.34

66.1%

4.74

57.0%

12.43

50.5%

Personal

Effects

61

0.09

4.5%

0.72

8.7%

2.76

11.2%

Mass

Market

62

0.13

6.5%

0.92

11.0%

2.65

10.8%

Beauty

0.29

14.0%

1.07

12.8%

2.01

8.2%

Other

0.12

5.7%

0.26

3.1%

1.49

6.1%

Home

63

0.03

1.7%

0.29

3.5%

1.11

4.5%

Travel/

Entertainment

0.01

0.5%

0.06

0.7%

0.80

3.2%

Services

64

0.01

0.5%

0.10

1.2%

0.64

2.6%

Automotive

0.002

0.1%

0.03

0.4%

0.27

1.1%

Health

65

0.01

0.2%

0.09

1.1%

0.23

0.9%

Everyday

66

0.003

0.2%

0.04

0.5%

0.23

0.9%

As a whole, the vertical mix is diversifying over time. Apparel and Beauty combined to make up

58.6 percent of GMV in 2021, down from 69.9 percent in 2020 and 80.1 percent in 2019.

Meanwhile, the five lowest-volume verticals (Travel/Entertainment, Services, Automotive,

61

The Personal Effects vertical includes merchants from the following sub-verticals: Electronics, Fitness/Sporting

Equipment, Games/Hobbies, and Jewelry

62

The Mass Market vertical includes merchant from the following sub-verticals: Department Stores, Discount /

wholesale, General Goods, and General Merchandise

63

The Home vertical includes merchants from the following sub-verticals: Furniture/Home Furnishings and Home

Improvement

64

The Services vertical includes merchants from the following sub-verticals: Education, Insurance, Pet Care, Services,

Subscription Fees

65

The Health vertical includes merchants from the following sub-verticals: Elective Medical and Health Products

66

The Everyday vertical includes merchants from the following sub-verticals: Auto – Transportation, Groceries,

Food/Drink (non-grocery), and Utilities

36

Health, and Everyday) comprised 8.8 percent of GMV in 2021, up from 3.9 percent in 2020 and

1.5 percent in 2019.

The sub-verticals that make up the Everyday vertical have received substantial attention over

the past year as examples of BNPL’s expansion from discretionary to essential purchases.

Although it still accounts for less than one percent of overall GMV, the Everyday vertical has

grown at a rapid pace: from $3.2 million in 2019 to $229.2 million in 2021. Its annualized

growth rate of 736 percent was the third highest of the 11 verticals surveyed.

67

One lender

accounted for 60 percent of the overall GMV in the Everyday vertical in 2021, and Everyday’s

share of that lender’s annual GMV grew from 0.9 percent in 2019 to 2.4 percent in 2020 to 4.6

percent in 2021.

Education, a sub-vertical within the Services vertical, has received attention from the States and

consumer advocates.

68

They have expressed concern about both BNPL and POS lenders

enabling the financing of educational expenses, particularly at non-accredited institutions. In

2021, the five lenders surveyed originated $59.8 million in BNPL loans to retailers in the

Education sub-vertical (0.24 percent of overall GMV), up from $7.1 million in 2020 (0.09

percent of overall GMV) and $0.47 million (0.02 percent of overall GMV) in 2019. The 1,028

percent CAGR increase from 2019 to 2021 was the fourth highest of the 23 sub-verticals

surveyed. There was substantial concentration within the Education sub-vertical, as one lender

accounted for 74 percent of its overall GMV in 2021.

69