DSM-5 CHANGES:

IMPLICATIONS FOR CHILD

SERIOUS EMOTIONAL

DISTURBANCE

DISCLAIMER

SAMHSA provides links to other Internet sites as a service to its users and is not responsible for the availability

or content of these external sites. SAMHSA, its employees, and contractors do not endorse, warrant, or guarantee

the products, services, or information described or offered at these other Internet sites. Any reference to a

commercial product, process, or service is not an endorsement or recommendation by SAMHSA, its employees,

or contractors. For documents available from this server, the U.S. Government does not warrant or assume any

legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus,

product, or process disclosed.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality

Rockville, Maryland 20857

June 2016

This page intentionally left blank

DSM-5 CHANGES:

IMPLICATIONS FOR CHILD

SERIOUS EMOTIONAL

DISTURBANCE

Contract No. HHSS283201000003C

RTI Project No. 0212800.001.108.008.008

RTI Authors:

Heather Ringeisen

Cecilia Casanueva

Leyla Stambaugh

SAMHSA Authors:

Jonaki Bose

Sarra Hedden

RTI Project Director:

David Hunter

SAMHSA Project Officer:

Peter Tice

For questions about this report, please e-mail [email protected].

Prepared for Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration,

Rockville, Maryland

Prepared by RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina

June 2016

Recommended Citation: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality.

(2016). 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: DSM-5 Changes:

Implications for Child Serious Emotional Disturbance (unpublished internal

documentation). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration, Rockville, MD.

ii

Acknowledgments

This publication was developed for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration (SAMHSA), Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (CBHSQ), by

RTI International, a trade name of Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, North

Carolina, under Contract No. HHSS283201000003C. Contributors to this report include Lisa

Colpe and Peggy Barker. At RTI, Michelle Back edited and Roxanne Snaauw formatted the

report.

iii

Table of Contents

Chapter Page

1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1

1.1 Definition of SED ................................................................................................... 1

1.2 Published SED Estimates ........................................................................................ 2

2. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Changes: Overview ............................................................................. 5

2.1 Elimination of the Multi-Axial System and GAF Score ......................................... 5

2.2 Disorder Reclassification ........................................................................................ 5

3. DSM-5 Child Mental Disorder Classification .................................................................... 9

3.1 New Childhood Mental Disorders Added to the DSM-5 ........................................ 9

3.1.1 Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder (SCD, under

Neurodevelopmental Disorders) ................................................................. 9

3.1.2 Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (or DMDD) (under

Depressive Disorders) ............................................................................... 11

3.2 Age-Related Diagnostic Criteria Changes to Mental Disorders in the DSM-5 .... 16

3.2.1 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD, under

Neurodevelopmental Disorders ................................................................ 16

3.2.2 Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD, under Trauma- and

Stressor-Related Disorders) ...................................................................... 20

3.3 Changes to Other Mental Disorders with Minor to No Implication for SED

Prevalence Estimates ............................................................................................ 24

3.3.1 Major Depressive Episode/Disorder (under Depressive Disorders) ......... 24

3.3.2 Persistent Depressive Disorder (formerly Dysthymic Disorder,

under Depressive Disorders) ..................................................................... 25

3.3.3 Manic Episode and Bipolar I Disorder (under Bipolar and Related

Disorders) .................................................................................................. 26

3.3.4 Generalized Anxiety Disorder (under Anxiety Disorders) ....................... 34

3.3.5 Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia (under Anxiety Disorders) ................... 35

3.3.6 Separation Anxiety Disorder (under Anxiety Disorders) ......................... 39

3.3.7 Social Anxiety Disorder (formerly Social Phobia [Social Anxiety

Disorder], under Anxiety Disorders) ........................................................ 40

3.3.8 Conduct Disorder (under Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and

Conduct Disorders) ................................................................................... 42

3.3.9 Oppositional Defiant Disorder (under Disruptive, Impulse-Control,

and Conduct Disorders) ............................................................................ 45

3.3.10 Eating Disorders (under Feeding and Eating Disorders) .......................... 47

3.3.11 Body Dysmorphic Disorder (under Obsessive-compulsive and

Related Disorders) .................................................................................... 52

4. Instrumentation ................................................................................................................. 55

5. Summary and Conclusions ............................................................................................... 59

References ..................................................................................................................................... 61

iv

List of Tables

Table Page

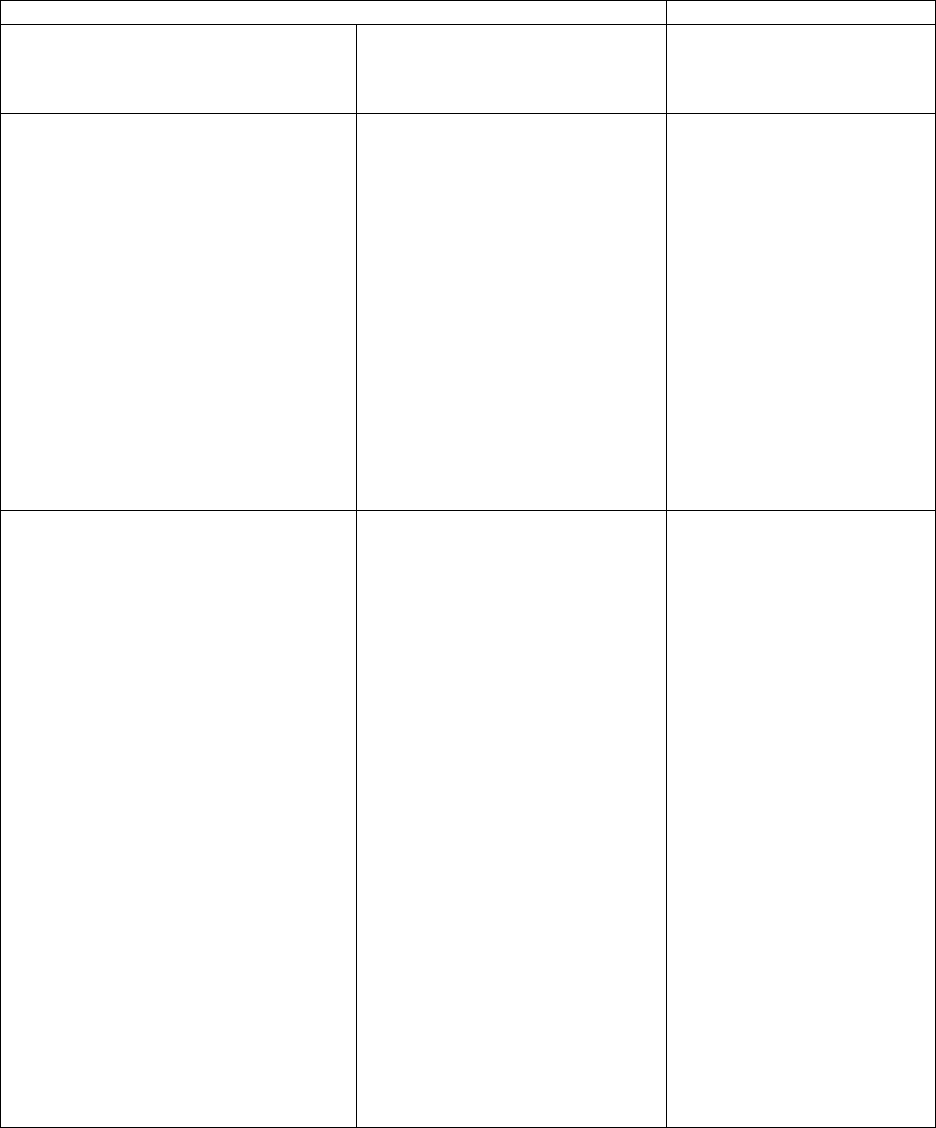

1. DSM-IV Childhood Mental Disorders Assessed in Leading Studies with Published

Estimates of SED ................................................................................................................ 3

2. Past 12-month Prevalence of Mental Disorders Based upon the NCS-A, NHANES

Special Study, and GSMS, by Functional Impairment and Child Age ............................... 4

3. Disorder Classes Presented by the DSM-IV and DSM-5, as Ordered in DSM-IV ............ 6

4. Disorder Classification in the DSM-IV and DSM-5 for Disorders Usually First

Diagnosed in Infancy, Childhood, or Adolescence ............................................................ 7

5. DSM-IV Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS)

to DSM-5 Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder (SCD) Comparison .................. 10

6. DSM-IV Bipolar Disorder-Manic Episode and Oppositional Defiant Disorder to

DSM-5 Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (or DMDD) Comparison ................... 12

7. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Comparison .................... 17

8. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Comparison Children 6 Years

and Younger ...................................................................................................................... 21

9. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Major Depressive Episode/Disorder Comparison ............................ 25

10. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Dysthymic Disorder/Persistent Depressive Disorder

Comparison ....................................................................................................................... 26

11. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Manic Episode Criteria Comparison ................................................ 28

12. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Bipolar I Disorder Comparison ........................................................ 29

13. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Generalized Anxiety Disorder Comparison ..................................... 34

14. Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia Criteria Changes from DSM-IV to DSM-5 ................. 36

15. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Separation Anxiety Disorder Comparison ........................................ 39

16. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Social Phobia/Social Anxiety Disorder Comparison ........................ 41

17. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Conduct Disorder Comparison ......................................................... 43

18. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Oppositional Defiant Disorder Comparison ..................................... 46

19. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Anorexia Nervosa Comparison ........................................................ 48

20. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Bulimia Nervosa Comparison .......................................................... 49

21. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Binge Eating Disorder Comparison .................................................. 50

22. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Comparison ................. 52

23.

D

SM-IV to DSM-5 Body Dysmorphic Disorder Comparison ......................................... 54

24. Summary of Diagnostic Instruments Used to Assess Child Mental Disorders ................ 55

v

This page intentionally left blank

1

1. Introduction

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is the manual used by

clinicians and researchers to diagnose and classify mental disorders (including substance use

disorders [SUDs]). The DSM specifically classifies child disorders by symptoms, duration, and

functional impact across home, school, and other community settings. The American Psychiatric

Association (APA) published the DSM-5 in 2013, culminating a 14-year revision process. This

latest revision takes a new approach to defining the criteria for mental disorders—a lifespan

perspective. This perspective is very relevant to diagnosing childhood mental disorders. The

perspective recognizes the importance of age and development in the onset, manifestation, and

treatment of mental disorders. The purpose of this report is to describe the differences between

the DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria that could affect national estimates of childhood

serious emotional disturbance (SED). The report also provides a description of DSM-5 updates

that have been made (or are being made) to existing diagnostic instruments and screeners of

childhood emotional and behavioral health.

1.1 Definition of SED

The DSM has never offered a definition of SED. This term has been defined historically

by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and released as

a Federal Register notice. The SAMHSA definition was crafted in order to inform state block

grant allocations for community mental health services provided to children with an SED and

adults with a serious mental illness (SMI). The Federal Register definition is intended to identify

and estimate the size of the group of children with SED within the general population of each

state. An accurate and up-to-date estimate of childhood SED is critical for SAMHSA to plan

future block grant allocations and financial supports to states serving children with SED.

The Federal Register notice defines the terms "children with a serious emotional

disturbance" and "adults with a serious mental illness" (SAMHSA, 1993, p. 29422). Pub. L. 102-

321 defines children with an SED to be people "from birth up to age 18 who currently or at any

time during the past year have had a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder of

sufficient duration to meet diagnostic criteria specified within the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised (DSM-III-R; American Psychiatric

Association, 1987) that resulted in functional impairment, which substantially interferes with or

limits the child's role or functioning in family, school, or community activities" (SAMHSA,

1993, p. 29425).

The 1992 and 1993 Federal Register notices also offer several notes that are helpful in

considering the age, symptom duration, and diagnostic exclusions related to the definition of

childhood SED:

• Age: "Although the definition of SED in children is restricted to persons up to age 18, it

is recognized that some states extend this age range to persons less than age 22. To

accommodate this variability, states using an extended age range for children's services

should provide separate estimates for persons below age 18 and persons aged 18 to 22

within block grant applications" (SAMHSA, 1993, p. 29425).

2

• Duration: "The reference year…refers to a continuous 12-month period because this is a

frequently used interval in epidemiological research and because it relates to commonly

used [state] planning cycles" (SAMHSA, 1993, p. 29425).

• Diagnostic exclusions: "These disorders include any mental disorders listed in the DSM-

III-R…with the exception of DSM-III-R "V" codes, substance use and developmental

disorders, which are excluded unless they co-occur with another diagnosable serious

emotional disturbance" (SAMHSA, 1993, p. 29425).

A November 6, 1992, Federal Register notice requests public comments to a preliminary

definition of childhood SED (SAMHSA, 1992). The May 20, 1993, Federal Register describes

responses to public comments received in response to the 1992 notice. Public comments to the

proposed SED definition primarily focused on the impairment criteria, with support for

considering a broad definition of impairment and also concerns that including less impairing

disorders would dilute resources for those with the most severely debilitating conditions. A

smaller set of comments focused on the inclusion or exclusion of certain disorders such as

substance abuse, developmental disorders, and attention deficit disorder.

The 1993 Federal Register offers clarification on final decisions about disorders to be

included and excluded in the SED definition. Public comments included concerns about whether

attention-deficit disorder (ADD) should be included for two main reasons: (1) parental concerns

about the negative stigma associated with labelling ADD as a "serious emotional disturbance"

and (2) treatment providers/educators noting difficulties making definitive ADD diagnoses.

Ultimately, ADD was included in the definition of SED because "a significant group of children

with functional impairments associated with this disorder might otherwise be excluded from

service" (p. 29423). SUDs were excluded based upon the rationale that the federal government

administered a separate state block grant intended to fund substance abuse treatment and

prevention services. Developmental disorders (mental retardation, autism, pervasive

developmental disorders) were also excluded. The rationale described for this decision was as

follows: "while comments received cited the frequent involvement of mental health practitioners

in treatment planning and service delivery for these individuals (particularly autistic children),

separate Federal block grant funds and processes for needs assessment cover these population

groups" (SAMHSA, 1993, p. 29424). Finally, DSM-III "V" codes were excluded because "they

represent conditions that may be a focus of treatment but are not attributed to a mental disorder"

(p. 29424).

In summary, DSM mental disorder classifications are relevant to SED as they form the

basis for an essential part of the SED criteria—the presence of a DSM-based mental disorder.

Changes in the number of mental disorders (as defined by the DSM) that fall under the

operationalized definition of SED, and breadth of the diagnostic criteria for existing DSM-based

mental disorders might impact the prevalence rates of SED. The current operationalized

definition of SED may need to be updated to ensure consistent and precise measurement of the

prevalence of SED within epidemiological studies at the national level.

1.2 Published SED Estimates

Three large-scale epidemiological studies have provided estimates of SED based upon

the administration of child and adolescent diagnostic interviews. These studies include a

3

supplemental study to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES;

Merikangas et al., 2010), the National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Cohort (NCS-A; Kessler

et al., 2012), and the Great Smoky Mountain Study (GSMS; Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler,

& Angold, 2003). These three studies assess slightly different age groups, use different

diagnostic instruments, and include the assessment of slightly different childhood mental

disorders (see Table 1). The disorders assessed in these studies reflect diagnostic categories to be

considered when estimating the prevalence of SED.

Table 1. DSM-IV Childhood Mental Disorders Assessed in Leading Studies with Published

Estimates of SED

Disorder

Category

NCS-A (13–17 years)

Composite International

Diagnostic Interview

(CIDI)

NHANES (8–15 years)

Diagnostic Interview

Schedule for Children

(DISC)

GSMS (9–16 years)

Child and Adolescent

Psychiatric Assessment

(CAPA)

Mood

Disorder

Major depression

Dysthymia

Bipolar disorder

Major depression

Dysthymia

Major depression

Dysthymia

Bipolar disorder

Mania

Depression NOS

Anxiety

Disorders

Generalized anxiety disorder

Panic disorder

Agoraphobia

Specific phobia

Separation anxiety disorder

Posttraumatic stress disorder

Social phobia

Generalized anxiety disorder

Panic disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder

Panic disorder

Agoraphobia

Simple phobia

Separation anxiety disorder

Posttraumatic stress disorder

Obsessive compulsive

disorder

Behavior

Disorders

ADHD

Conduct disorder

Oppositional defiant disorder

ADHD

Conduct disorder

ADHD

Conduct disorder

Oppositional defiant disorder

Substance

Disorders

Alcohol abuse

Drug abuse

Alcohol abuse

Drug abuse

Other Eating disorders Eating disorder Eating disorders

Trichotillomania

Enuresis

Encopresis

Psychosis

ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; NOS = not otherwise specified.

Each study defines SED to include any assessed DSM-IV Axis I disorder. The R.C.

Kessler et al. (2012) and Costello et al. (2003) publications include substance disorders within

the SED estimates, while the Federal Register definition of SED excludes substance abuse.

"Serious functional impairment" is defined differently in each study based upon how the study's

diagnostic interview measured impairment. One study, (Costello et al., 2003), defined SED using

the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) as any Axis I disorder with

"significant functional impairment." CAPA-based definitions of SED include a child who

(1) meets diagnostic criteria for at least one of the assessed Axis I disorders by parent or child

report, and (2) has a report of any partial or severe impairment rating by parent or child report

4

(personal communication with G. Keeler, October 2012). R.C. Kessler et al. (2012) defined the

serious impairment criteria for SED as a Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) score of

50 or less (having moderate functional impairment in most areas of living or severe impairment

in at least one area). Moderate impairment was defined as one or more Axis I disorders plus a

CGAS score of 51 to 60 (variable functioning with sporadic difficulties in several but not all

areas of living). Meanwhile, Merikangas and colleagues (2010) operationalized four levels of

impairment for each disorder assessed: level A, intermediate or severe rating on ≥ one question;

level B, intermediate or severe rating on ≥ two questions (level A and B are not mutually

exclusive); level C, severe rating on ≥ one question; and level D (severe impairment), included

meeting criteria for either level B or C. Impairment items assessed impairment in six domains,

including interference with the respondent's own life, family life, social life, peers, teachers, and

school performance. "Any DSM-IV Disorder with Severe Impairment," or SED, was defined as a

case with level D impairment.

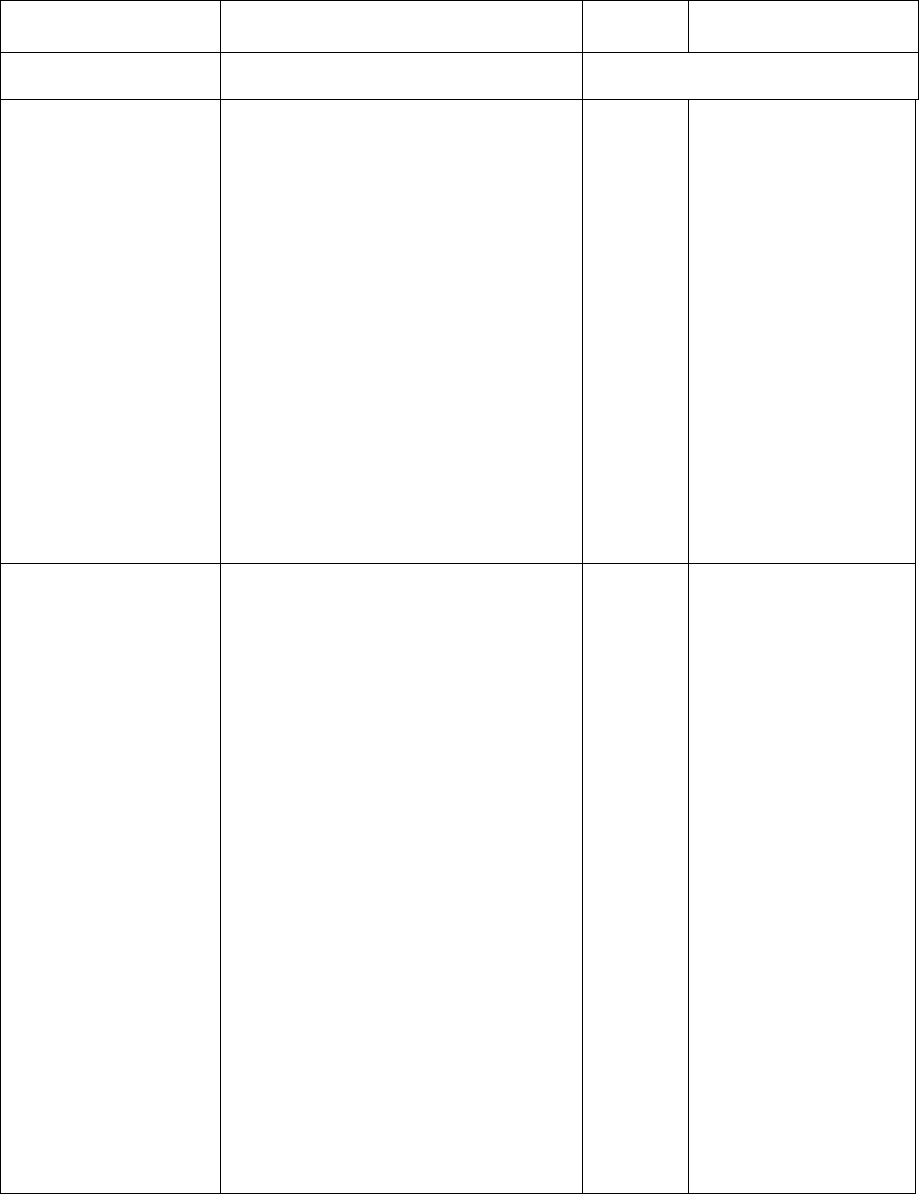

These definitions of SED result in prevalence estimates that range from 6.8 to 11.5

percent depending on the study and age of children included (see Table 2). The following

sections of this report describe how recent updates to the DSM may or may not result in likely

changes to these prevalence estimates of SED. This report does not summarize DSM-IV to

DSM-5 changes to SUDs since they are excluded from the Federal Register definition of SED.

Another SAMSHA report Impact of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 Conversion on the National Survey

on Drug Use and Health and the Mental Health Surveillance Study includes a detailed

description of changes from DSM-IV to DSM-5 for SUDs among youths aged 12 to 17 years

(Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, in review).

Table 2. Past 12-month Prevalence of Mental Disorders Based upon the NCS-A, NHANES

Special Study, and GSMS, by Functional Impairment and Child Age

Prevalence Estimate (%, SE)

NCS-A (13-17 years)

Past 12 Months

NHANES Special

Study (12-15

years)

Past 12 Months

NHANES Special

Study (8-11 years)

Past 12 Months

GSMS (9-16

years)

Past 3 Months

Any DSM-IV

Disorder

42.6 (1.2) 13.4 (1.2) 12.8 (1.3) 13.3

SED (and

associated

definition)

8.0 (1.3)

Moderate impairment

rating in most areas of

living or severe in 1

area

11.5 (1.3)

Level A or B:

Intermediate

impairment rating on

2 of 6 items or at

least 1 severe rating

11.0 (1.1)

Level A or B:

Intermediate

impairment rating on

2 of 6 items or at

least 1 severe rating

6.8

Any Axis I plus

"significant

functional

impairment"

Disorder with

moderate or

severe

impairment in

any area of living

17.8 (n/a)

Moderate impairment

was defined as variable

functioning, with

sporadic difficulties in

several, but not all

areas of living.

Not provided Not provided Not provided

5

2. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Changes: Overview

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) published the DSM-5 in 2013. This latest

revision takes a lifespan perspective recognizing the importance of age and development on the

onset, manifestation, and treatment of mental disorders. Other changes in the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. (DSM-5) include eliminating the multi-axial

system; removing the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF score); reorganizing the

classification of the disorders; and changing how disorders that result from a general medical

condition are conceptualized. Many of these general changes from Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (DSM-IV) to DSM-5 are summarized in the report Impact

of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 Changes on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. This report

will supplement that information by providing details specifically about changes to disorders of

childhood and their implications for generating estimates of child serious emotional disturbance

(SED).

2.1 Elimination of the Multi-Axial System and GAF Score

One of the key changes from DSM-IV to DSM-5 is the elimination of the multi-axial

system. DSM-IV approached psychiatric assessment and organization of biopsychosocial

information using a multi-axial formulation (American Psychiatric Association, 2013b). There

were five different axes. Axis I consisted of mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs);

Axis II was reserved for personality disorders and mental retardation; Axis III was used for

coding general medical conditions; Axis IV was to note psychosocial and environmental

problems (e.g., housing, employment); and Axis V was an assessment of overall functioning

known as the GAF. The GAF scale was dropped from the DSM-5 because of its conceptual lack

of clarity (i.e., including symptoms, suicide risk, and disabilities in the descriptors) and

questionable psychometric properties (American Psychiatric Association, 2013b).

Although the impact of removing the overall multi-axial structure in DSM-5 is unknown,

there is concern among clinicians that eliminating the structured approach for gathering and

organizing clinical assessment data will hinder clinical practice (Frances, 2010). However, the

direct impact on the prevalence rates of childhood mental disorders is likely to be negligible as it

will not affect the characteristics of diagnoses.

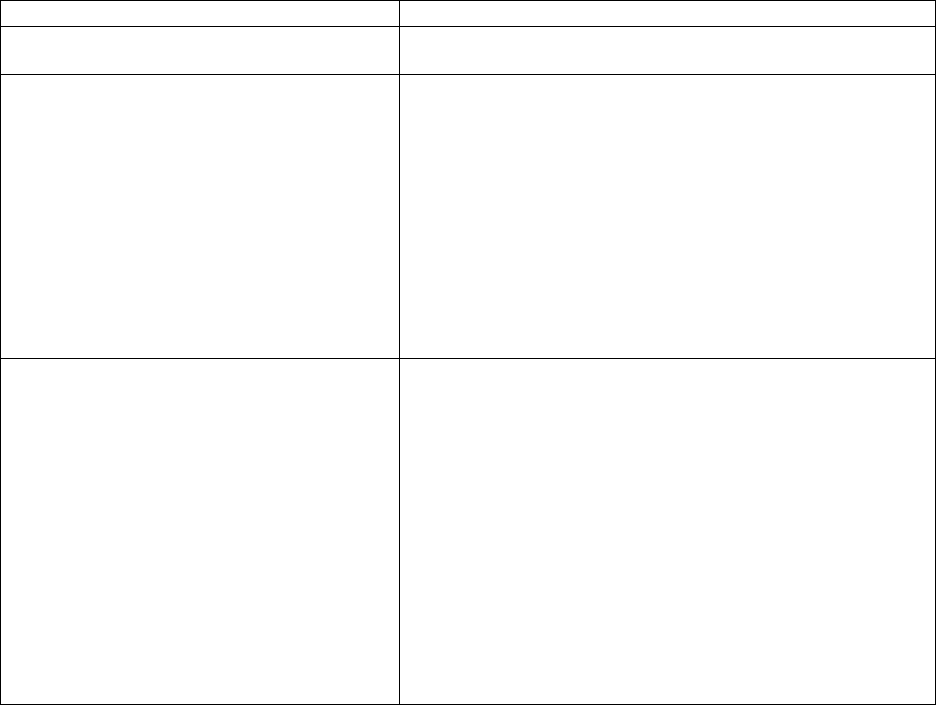

2.2 Disorder Reclassification

DSM-IV and DSM-5 categorize disorders into "classes" with the intent of grouping

similar disorders (particularly those that are suspected to share etiological mechanisms or have

similar symptoms) to help clinician and researchers use of the manual. From DSM-IV to DSM-5,

there has been a reclassification of many disorders that reflects a better understanding of the

classifications of disorders from emerging research or clinical knowledge. Table 3 lists the

disorder classes included in DSM-IV and DSM-5. In DSM-5, six classes were added and four

were removed. As a result of these changes in the overall classification system, numerous

individual disorders were reclassified from one class to another (e.g., from "mood disorders" to

"bipolar and related disorders" or "depressive disorders"). The reclassification of disorder classes

6

will not have a direct effect on any SED estimation; however, it does warrant consideration when

documenting disorders that may have changed classes.

Table 3. Disorder Classes Presented by the DSM-IV and DSM-5, as Ordered in DSM-IV

DSM-IV DSM-5

1. Disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy,

childhood, or adolescence

Dropped

1

2. Delirium, Dementia, and Amnestic and other

cognitive disorders

17. Neurocognitive Disorders

3. Mental Disorders due to a general medical

condition

Dropped

1

4. Substance-related disorders 16. Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

5. Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders 2. Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic

Disorders

6. Mood Disorders 3. Bipolar and Related Disorders

4. Depressive Disorders

7. Anxiety Disorders 5. Anxiety Disorders

8. Somatoform Disorders 9. Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders

9. Factitious Disorders Dropped

1

10. Dissociative Disorders 8. Dissociative Disorders

11. Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders 13. Sexual Dysfunctions

14. Gender Dysphoria

19. Paraphilic Disorders

12. Eating Disorders 10. Feeding and Eating Disorders

13. Sleep Disorders 12. Sleep-Wake Disorders

14. Impulse-Control Disorders not elsewhere

classified

15. Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders

15. Adjustment Disorders Dropped

1

16. Personality Disorders 18. Personality Disorders

N/A 1. Neurodevelopmental Disorders

N/A 6. Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

N/A 7. Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

N/A 11. Elimination Disorders

N/A 20. Other Mental Disorders

N/A 21. Medication-Induced Movement Disorders and Other

Adverse Effects of Medication

1

A notation of "dropped" does not imply that the specific disorders were removed; rather the overall classification

is not included in DSM-5. Disorders in those classes were mainly recategorized.

Of particular note for childhood mental disorders, the DSM-5 eliminated a class of

"disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence." Those disorders are

now placed within other classes. See Table 4 for a summary the new DSM-5 disorder classes for

those disorders formally classified as "disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or

adolescence."

7

Table 4. Disorder Classification in the DSM-IV and DSM-5 for Disorders Usually First

Diagnosed in Infancy, Childhood, or Adolescence

Disorder Types (version) DSM-IV Disorder Class DSM-5 Disorder Class

Mental Retardation (DSM-IV)

Intellectual Disabilities (DSM-5)

Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy, childhood, or adolescence

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Learning Disorders Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy, childhood, or adolescence

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Motor Skills Disorder Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy, childhood, or adolescence

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Communication Disorders Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy, childhood, or adolescence

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Pervasive Developmental Disorders

(DSM-IV)

Autism Spectrum Disorder (DSM-

5)

Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy, childhood, or adolescence

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity

Disorder

Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Conduct Disorder Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy

Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and

Conduct Disorders

Oppositional Defiant Disorder Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy

Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and

Conduct Disorders

Feeding and Eating Disorders of

Infancy or Early Childhood

Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy

Feeding and Eating Disorders

Tic Disorders Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Elimination Disorders Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy

Elimination Disorders

Separation Anxiety Disorder Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy

Anxiety Disorders

Selective Mutism Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy

Anxiety Disorders

Reactive Attachment Disorder Disorders usually first diagnosed in

infancy

Trauma- and Stressor-Related

Disorders

8

This page intentionally left blank

9

3. DSM-5 Child Mental Disorder

Classification

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. (DSM-5) includes

changes to some key disorders of childhood. Two new childhood mental disorders were added in

the DSM-5: social communication disorder (or SCD) and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder

(or DMDD). There were age-related diagnostic criteria changes for two other mental disorder

categories particularly relevant to the definition of serious emotional disturbance (SED):

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). An

ADHD diagnosis now requires symptoms to be present prior to the age of 12 (rather than 7, the

age of onset from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. [DSM-

IV]). PTSD includes a new subtype specifically for children younger than 6 years of age.

Sections 3.1 and 3.2 provide detailed descriptions of these disorders as well as summaries

of the research that has been conducted around their impact on the prevalence of childhood

mental disorders. Other disorders did not have specific DSM-5 changes related to childhood, but

these changes would be relevant to both adults and children (e.g., major depressive disorder

[MDD], generalized anxiety disorder [GAD]). Section 3.3 provides a brief overview of DSM-5

changes to these remaining disorders. In the report sections that follow we reference prevalence

rates found in studies of community samples using the DSM-5. For some disorders, we also

reference prevalence rates in clinical samples where direct comparisons were performed between

DSM-IV and DSM-5 ratings. The prevalence rates from clinical samples are relevant to this

report in demonstrating the magnitude of change that might be expected in prevalence rates from

DSM-IV to DSM-5.

3.1 New Childhood Mental Disorders Added to the DSM-5

3.1.1 Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder (SCD, under Neurodevelopmental

Disorders)

Description. The DSM-5 communication disorders include a new condition for persistent

difficulties in the social uses of verbal and nonverbal communication: social (pragmatic)

communication disorder or SCD. SCD is characterized by a primary difficulty with pragmatics—

the social use of language or communication—resulting in functional limitations in effective

communication, social participation, development of social relationships, and academic

achievement (see Table 5 for a description of DSM-5 SCD diagnostic criteria). Symptoms of SCD

include difficulties in the acquisition and use of spoken language and inappropriate responses in

conversation. Although diagnosis is rare for children younger than 4 years old, symptoms must be

present in early childhood even if not recognized until later. Individuals with SCD have never had

effective social communication. This new disorder cannot be diagnosed if social communication

deficits are part of the two main characteristics of the new autism spectrum disorder (ASD). ASD

is characterized by (1) deficits in social communication and social interaction and (2) restricted

repetitive behaviors, interests, and activities (RRBs). Because both components are required for an

ASD diagnosis, SCD is diagnosed if no RRBs are present or there is no past history of RRBs. As

described by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the symptoms of some patients

10

diagnosed with DSM-IV pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS)

may meet the DSM-5 criteria for SCD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013c).

Table 5. DSM-IV Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) to

DSM-5 Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder (SCD) Comparison

DSM-IV DSM-5

Disorder Class: Pervasive Developmental

Disorders

Disorder Class: Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Severe and pervasive impairment in the

development of reciprocal social interaction or

verbal and nonverbal communication skills, or

when stereotyped behavior, interests, and

activities are present but are not met for a

specific pervasive developmental disorder.

This category includes "atypical autism" (late

age of onset, atypical symptomatology).

A. Persistent difficulties in the social use of verbal and

nonverbal communication as manifested by all of the

following:

1. Deficits in using communication for social purposes

2. Impairment of the ability to change communication to

match context

3. Difficulties for following rules for conversation

(taking turns, use of verbal/nonverbal signs to regulate

interaction)

4. Difficulties understanding what is not explicitly stated

B. The deficits result in functional limitations in effective

communication, social participation, social relationships,

and academic achievement.

C. The onset of the symptoms is in the early development

period, but may not fully manifest until social

communication demands exceed limited capabilities.

D. The symptoms are not attributable to another medical or

neurological condition or to low abilities in the domains

of word structure and grammar, and are not better

explained by autism spectrum disorder, intellectual

disability, or developmental delay.

Estimated Prevalence. Although a few studies have reported empirical support for a

conceptualization of SCD distinguishable from ASD (Gibson, Adams, Lockton, & Green, 2013)

and ADHD (St Pourcain et al., 2011), there is one practitioner review publication describing

concern that the inclusion/exclusion criteria and differential diagnosis with ASD, ADHD, social

anxiety disorders, intellectual disabilities, and developmental delays, may mean that very few

individuals will meet diagnostic criteria for SCD (Norbury, 2014).

No study was found on the general population's prevalence of SCD. In one study that

analyzed three datasets (1) data from the Simons Simplex Collection, a genetic consortium study

focusing on families having just one child with an ASD; (2) the Collaborative Programs of

Excellence in Autism, a multicenter study of ASD; and (3) the University of Michigan Autism

and Communication Disorders Center data bank that included a total of 4,453 children with

DSM-IV clinical PDD diagnoses and 690 with non-PDD diagnoses (e.g., language disorder), the

proposed ASD DSM-5 criteria identified 91 percent of children with clinical DSM-IV PDD

diagnoses (Huerta, Bishop, Duncan, Hus, & Lord, 2012). In this samples of children with DSM-

IV diagnosis for PPD (86.6 percent of the pooled sample) and non-PPD (13.4 percent of the

pooled sample), only 75 of 5,143 (1.5 percent) met social communication criteria for ASD, but

did not meet threshold criteria for RRBs. This study concluded that few children with ASD are

likely to be misclassified as having SCD or will be reclassified as SCD under the DSM-5 (Huerta

11

et al., 2012). In contrast, a second study based on the multisite field trial of the DSM-IV of adults

and children (mean age 9 years old), of which 657 had a clinical diagnosis of PDD and 276 had a

diagnosis other than PDD (mental retardation, language disorders, childhood schizophrenia),

almost 40 percent of cases with a clinical diagnosis of PDD and 71.7 percent of those with PDD-

NOS did not met revised DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD, concluding that proposed DSM-5

criteria could substantially alter the composition and estimate of the autism spectrum

(McPartland, Reichow, & Volkmar, 2012). In the DSM-5 field trials in the United States and

Canada based on child clinical populations (general child psychiatry outpatient services), one of

the sites (Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, MA) found the DSM-IV and DSM-5 prevalence

of ASD was almost the same (23 percent and 24 percent), but a second site (Stanford University

Hospital, Palo Alto, CA) found the prevalence of ASD decreased from 26 percent to 19 percent.

A review of the data (no tables provided in the publication) showed that the decrease at Stanford

was offset by movement into the new SCD diagnosis (Regier et al., 2013).

Overall, these studies suggest that between 1.5 percent to 40 percent or more of children

who would have been classified as PDD before, will not meet diagnostic criteria of ASD under

the DSM-5 and some of them would likely be reclassified as SCD and be included in the SED

estimate, if SCD is part of the SED definition (McPartland, Reichow, & Volkmar, 2012).

It

should be noted that there is concern in the field that SCD could be over diagnosed by speech-

language pathologists. If SCD is treated as a residual category (like the previous PDD-NOS) for

communication disorders diagnosed by speech-language pathologists, children who should be

diagnosed as ASD would be classified as SCD since identifying ASD may prove challenging for

speech-language pathologists (Norbury, 2014).

Implications for Estimate of SED. As SCD would be under the purview of speech-

language pathology, the inclusion/exclusion of SCD on the Federal Register definition of SED

needs to be determined. If SCD is included in the definition of SED, some increase can be

expected in the estimate of SED from the reclassification of children previously classified as

PDD and PDD-NOS to SCD. An additional increase in the SED estimate can be expected from

the diagnoses of SCD by speech-language pathologists if they are not obtaining differential

diagnosis from other professionals.

3.1.2 Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (or DMDD) (under Depressive Disorders)

Description. DMDD is a new addition to DSM-5 that aims to combine bipolar disorder

that first appears in childhood with oppositional behaviors (Axelson, 2013). DMDD is

characterized by severe and recurrent temper outbursts that are grossly out of proportion in

intensity or duration to the situation. These occur, on average, three or more times each week for

1 year or more (see Table 6 for a description of DSM-5 DMDD diagnostic criteria). The key

feature of DMDD is chronic irritability that is present in between episodes of anger or temper

tantrums. A diagnosis requires symptoms to be present in at least two settings (at home, at

school, or with peers) for 12 or more months, and symptoms must be severe in at least one of

these settings. Onset of DMDD must occur before age 10, and a child must be at least 6 years old

to receive a diagnosis of DMDD. The main driver behind the conceptualization of DMDD was

concern that diagnosis of bipolar disorder was being applied inconsistently across clinicians

because of the disagreement about how to classify irritability in the DSM-IV. In addition,

chronic childhood irritability has not been shown to predict later onset of bipolar disorder,

12

suggesting that irritability may be best contained within a separate mood dysregulation category

(Leigh, Smith, Milavic, & Stringaris, 2012).

Table 6. DSM-IV Bipolar Disorder-Manic Episode and Oppositional Defiant Disorder to DSM-5

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (or DMDD) Comparison

DSM-IV Criteria DSM-5

Disorder Class: Mood Disorders

Manic Episode

Disorder Class: Attention-Deficit

and Disruptive Behavior Disorders

Oppositional Defiant Disorder

Disorder Class: Depressive

Disorders

Disruptive Mood

Dysregulation Disorder

A. A distinct period of abnormally and

persistently elevated, expansive, or

irritable mood, lasting at least 1 week

(or any duration if hospitalization is

necessary).

A. A pattern of negativistic, hostile,

and defiant behavior lasting at

least 6 months, during which

four (or more) of the following

are present

1. Often loses temper

2. Often argues with adults

3. Often actively defies or

refuses to comply with

adults' requests or rules

4. Often deliberately annoys

people

5. Often blames others for his

or her mistakes

6. Is often touchy or easily

annoyed by others

7. Is often angry or resentful

8. Is often spiteful or vindictive

A. Severe recurrent temper

outbursts manifested

verbally (e.g., verbal rages)

and or behaviorally (e.g.,

physical aggression) that

are grossly out of

proportion in intensity or

duration to the situation or

provocation

B. During the period of mood

disturbance, three (or more) of the

following symptoms have persisted

(four if the mood is only irritable) and

have been present to a significant

degree:

1. Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

2. Decreased need for sleep (e.g.,

feels rested after only 3 hours of

sleep)

3. More talkative than usual or

pressure to keep talking

4. Flight of ideas or subjective

experience that thoughts are racing

5. Distractibility (i.e., attention too

easily drawn to unimportant or

irrelevant external stimuli)

6. Increase in goal-directed activity

(either socially, at work or school,

or sexually) or psychomotor

agitation

7. Excessive involvement in

pleasurable activities that have a

high potential for painful

consequences (e.g., engaging in

unrestrained buying sprees, sexual

indiscretions, or foolish business

investments)

B. The temper outbursts are

inconsistent with

developmental level

(continued)

13

Table 6. DSM-IV Bipolar Disorder-Manic Episode and Oppositional Defiant Disorder to DSM-5

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (or DMDD) Comparison (continued)

DSM-IV Criteria DSM-5

Disorder Class: Mood Disorders

Manic Episode

Disorder Class: Attention-Deficit

and Disruptive Behavior Disorders

Oppositional Defiant Disorder

Disorder Class: Depressive

Disorders

Disruptive Mood

Dysregulation Disorder

C. The temper outbursts

occur, on average, three or

more times per week.

D. The mood between temper

outbursts is persistently

irritable or angry most of

the day, nearly every day,

and it is observable by

others

E. Criteria A-D have been

present for 12 or more

months. Throughout that

time, the individual has not

had a period lasting 3 or

more consecutive months

without all of the

symptoms in criteria A-D.

D. The mood disturbance is sufficiently

severe to cause marked impairment in

occupational functioning or in usual

social activities or relationships with

others, or to necessitate

hospitalization to prevent harm to self

or others, or there are psychotic

features.

B. The disturbance in behavior

causes clinically significant

impairment in social, academic,

or occupational functioning

F. Criteria A-D are present in

at least two of three

settings

(home/school/peers) and

are severe in at least one

setting

D. Criteria are not met for conduct

disorder, and if the individual is

age 18 years or older, criteria are

not met for Antisocial

Personality Disorder.

G. The diagnosis should not

be made for the first time

before age 6 or after 18

H. The age oat onset of

criteria A-E is before 10

years

(continued)

14

Table 6. DSM-IV Bipolar Disorder-Manic Episode and Oppositional Defiant Disorder to DSM-5

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (or DMDD) Comparison (continued)

DSM-IV Criteria DSM-5

I. There has never been a

distinct period lasting more

than 1 day during which

the full symptom criteria,

except duration, for a

manic or hypomanic

episode have been met.

Note: Developmentally

appropriate mood elevation,

such as occurs in the context of

a highly positive event or its

anticipation, should not be

considered as a symptom of

mania or hypomania.

Disorder Class: Mood Disorders

Manic Episode

Disorder Class: Attention-Deficit

and Disruptive Behavior Disorders

Oppositional Defiant Disorder

Disorder Class: Depressive

Disorders

Disruptive Mood

Dysregulation Disorder

J. The behaviors do not occur

exclusively during an

episode of major

depressive disorder and are

not better explained by

another mental disorder

(e.g., autism spectrum

disorder, PTSD, separation

anxiety disorder).

C. The behaviors do not occur

exclusively during the course of

a Psychotic or Mood Disorder

Note: This diagnosis cannot

coexist with oppositional

defiant disorder, intermittent

explosive disorder, or bipolar

disorder, thought it can coexist

with others, including major

depressive disorder, ADHD,

conduct disorder, and

substance use disorders

(SUDs). Individuals whose

symptoms meet criteria for

both DMDD and oppositional

defiant disorder (ODD) should

only be given the diagnosis of

DMDD. If an individual has

ever experienced a manic or

hypomanic episode, the

diagnosis o DMDD should not

be assigned.

(continued)

15

Table 6. DSM-IV Bipolar Disorder-Manic Episode and Oppositional Defiant Disorder to DSM-5

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (or DMDD) Comparison (continued)

DSM-IV Criteria DSM-5

E. The symptoms are not due to the

direct physiological effects of a

substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a

medication, or other treatment) or a

general medical condition (e.g.,

hyperthyroidism).

Note: Manic-like episodes that are clearly

caused by somatic antidepressant

treatment (e.g., medication,

electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy)

should not count toward a diagnosis of

bipolar I disorder.

K. The symptoms are not

attributable to the

physiological effects of a

substance or to another

medical or neurological

condition

Estimated Prevalence. A study combining data from three community surveys: (1) a

representative sample of 918 preschoolers (aged 2-5) attending a large primary care pediatric

clinic in central North Carolina; (2) a representative sample of 1,420 children aged 9, 11, and 13

years in 11 predominantly rural counties of North Carolina; and (3) representative study of 920

children aged 9 to 17 years from four rural counties in North Carolina, found that prevalence of

DMDD ranges from less than 1 percent to 3.3 percent depending on child age. DMDD is most

prevalent among young children (aged 2 to 5) whose parents report high rates of temper tantrums

and irritable moods (Copeland, Angold, Costello, & Egger, 2013). However, according to

DSM-5, DMDD cannot be diagnosed in children under 6 years old; therefore, the real DSM-5

prevalence in the population will be closer to 1 percent. In the DSM-5 field trials in the United

States and Canada based on child clinical populations (general child psychiatry outpatient

services), estimates for DSM-IV were considered "not applicable because the diagnosis is new to

DSM-5," and the DSM-5 prevalence was 5 percent for Baystate Medical Center, 8 percent for

Columbia, and 15 percent for Colorado (Regier et al., 2013). Importantly, estimates for ODD in

Columbia decreased from 22 percent using DSM-IV to 17 percent using DSM-5, but no

additional analyses were reported to determine if children with ODD under the DSM-IV were

reclassified as DMDD under DSM-5 (Regier et al., 2013).

Implications for Estimate of SED. The comorbidity of DMDD with other disorders is

extremely high as described in the DSM-5, indicating that the prevalence increase in the SED

estimates, if DMDD is included, will not increase as "it is rare to find individuals whose

symptoms meet criteria for DMDD alone" (American Psychiatric Association, 2013b, p. 160).

However, if children have symptoms that meet criteria for ODD or intermittent explosive

disorders and DMDD, only DMDD should be assigned. Thus with this new diagnosis, children

will be reclassified. When all symptom, severity, and frequency criteria are applied, DMDD is

only present in roughly 1 percent of school-aged children (Copeland et al., 2013). DMDD should

include many of the children who would have been diagnosed with bipolar disorder using the

DSM-IV. Because these children would receive the new diagnosis of DMDD instead of ODD or

bipolar disorder, the addition of DMDD to the DSM-5 should not affect prevalence estimates of

SED.

16

3.2 Age-Related Diagnostic Criteria Changes to Mental Disorders in the

DSM-5

3.2.1 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD, under Neurodevelopmental

Disorders)

Description. ADHD is a chronic neurodevelopmental disorder according to DSM-5 that

is characterized by a persistent and pervasive pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-

impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development. ADHD was placed in the

neurodevelopmental disorders chapter to reflect brain developmental correlates with ADHD and

the DSM-5 decision to eliminate the DSM-IV chapter that includes all diagnoses usually first

made in infancy, childhood, or adolescence. The diagnostic criteria for ADHD in DSM-5 are

similar to those in DSM-IV. The same 18 symptoms noted in the DSM-IV are used, and continue

to be divided into two symptom domains (inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity), of which at

least six symptoms in one domain are required for diagnosis. The majority of ADHD criteria

changes were geared toward improving detection of ADHD among adults. However, one change

may have relevance to the estimation of SED: the onset criterion has been changed from

"symptoms that caused impairment were present before age 7 years" to "several inattentive or

hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were present prior to age 12." Table 7 shows a comparison

between DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ADHD.

Estimated Prevalence. In the DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada based on

child clinical populations (general child psychiatry outpatient services), using DSM-IV, ADHD

prevalence at Baystate Medical Center was 59 percent and at Columbia it was 55 percent.

Applying the DSM-5 criteria, the prevalence of ADHD was 69 percent at Baystate and 58

percent at Columbia, representing a 10 percent and 3 percent absolute difference, respectively

(Regier et al., 2013). In a birth cohort study of 2,232 British children who were prospectively

evaluated at ages 7 and 12 years for ADHD, the outcome of extending the age-of-onset criterion

to age 12 resulted in the increase in ADHD prevalence by age 12 years by only 0.1 percent

(Polanczyk et al., 2010). This negligible increase is in line with previous findings indicating that

95 percent of adults with a diagnosis of ADHD recall their symptoms starting before age 12 (R.

C. Kessler et al., 2005).

Implications for Estimate of SED. Some increase can be expected in the SED estimate

based on expanding ADHD criteria in the DSM-5 and more cases might be diagnosed. Based on

studies from community samples comparing DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria, ADHD is expected to

have a modest increase (under 10 percent absolute difference).

17

Table 7. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Comparison

DSM-IV DSM-5

Disorder Class: Disorders Usually Diagnosed in

Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence

Disorder Class: Neurodevelopmental Disorders

A. Either (1) or (2): A. A persistent pattern of inattention and/or

hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with

functioning or development, as characterized by

(1) and/or (2):

1. Six (or more) of the following symptoms of

inattention have persisted for at least 6 months to a

degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with

developmental level:

1. Inattention: Six (or more) of the following

symptoms have persisted for at least 6 months to a

degree that is inconsistent with developmental level

and that negatively impacts directly on social and

academic/occupational activities:

Note: The symptoms are not solely a manifestation of

oppositional behavior, defiance, hostility, or failure to

understand tasks or instructions. For older adolescents

and adults (age 17 or older), at least five symptoms are

required.

Inattention

a. often fails to give close attention to details or makes

careless mistakes in schoolwork, work, or other

activities

a. Often fails to give close attention to details or

makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or

during other activities (e.g., overlooks or misses

details, work is inaccurate).

b. often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or

play activity

b. Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or

play activities (e.g., has difficulty remaining

focused during lectures, conversations, or lengthy

reading).

c. often does not seem to listen when spoken to

directly

c. Often does not seem to listen when spoken to

directly (e.g., mind seems elsewhere, even in the

absence of any obvious distraction).

d. often does not follow through on instructions and

fails to finish schoolwork, chores or duties in the

workplace (not due to oppositional behavior or

failure to understand instructions)

d. Often does not follow through on instructions and

fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the

workplace (e.g., starts tasks but quickly loses focus

and is easily sidetracked).

e. often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities e. Often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities

(e.g., difficulty managing sequential tasks; difficulty

keeping materials and belongings in order; messy,

disorganized work; has poor time management; fails

to meet deadlines).

f. often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in

tasks that require sustained mental effort (such as

schoolwork or homework)

f. Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in

tasks that require sustained mental effort (e.g.,

schoolwork or homework; for older adolescents and

adults, preparing reports, completing forms,

reviewing lengthy papers).

(continued)

18

Table 7. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Comparison (continued)

DSM-IV DSM-5

Disorder Class: Disorders Usually Diagnosed in

Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence

Disorder Class: Neurodevelopmental Disorders

g. often loses things necessary for tasks or activities

(e.g., toys, school assignments, pencils, books or

tools)

g. Often loses things necessary for tasks or activities

(e.g., school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets,

keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones).

h. is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli h. Is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli (for

older adolescents and adults, may include unrelated

thoughts).

i. is often forgetful in daily activities i. Is often forgetful in daily activities (e.g., doing

chores, running errands; for older adolescents and

adults, returning calls, paying bills, keeping

appointments).

2. Six (or more) of the following symptoms of

hyperactivity-impulsivity have persisted for at least

6 months to a degree that is maladaptive and

inconsistent with developmental level:

2. Hyperactivity and impulsivity: Six (or more) of the

following symptoms have persisted for at least 6

months to a degree that is inconsistent with

developmental level and that negatively impacts

directly on social and academic/occupational

activities:

Note: The symptoms are not solely a manifestation of

oppositional behavior, defiance, hostility, or a failure to

understand tasks or instructions. For older adolescents

and adults (age 17 or older), at least five symptoms are

required.

Hyperactivity

a. Often fidgets with hands or feet or squirms in seat a. Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet or squirms

in seat.

b. Often leaves seat in classroom or in other situations

in which remaining seated is expected

b. Often leaves seat in situations when remaining

seated is expected (e.g., leaves his or her place in

the classroom, in the office or other workplace, or in

other situations that require remaining in place).

c. Often runs about or climbs excessively in situations

in which it is inappropriate (in adolescents or adults,

may be limited to subjective feelings of

restlessness)

c. Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is

inappropriate. (Note: In adolescents or adults, may

be limited to feeling restless).

d. Often has difficulty playing or engaging in leisure

activities quietly

d. Often unable to play or take part in leisure activities

quietly.

e. Is often "on the go" or often acts as if "driven by a

motor"

e. Is often "on the go" acting as if "driven by a motor"

(e.g., is unable to be or uncomfortable being still for

extended time, as in restaurants, meetings; may be

experienced by others as being restless or difficult

to keep up with).

f. Often talks excessively f. Often talks excessively.

Impulsivity

g. Often blurts out answers before questions have been

completed

g. Often blurts out an answer before a question has

been completed (e.g., completes people's sentences;

cannot wait for turn in conversation).

h. Often has difficulty awaiting turn h. Often has trouble waiting his/her turn (e.g., while

waiting in line).

(continued)

19

Table 7. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Comparison (continued)

DSM-IV DSM-5

Disorder Class: Disorders Usually Diagnosed in

Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence

Disorder Class: Neurodevelopmental Disorders

i. Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts

into conversations or games)

i. Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts

into conversations, games, or activities; may start

using other people's things without asking or

receiving permission; for adolescents and adults,

may intrude into or take over what others are

doing).

B. Some hyperactive-impulsive or inattentive

symptoms must have been present before age 7

years.

B. Several inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive

symptoms were present before age 12 years.

C. Some impairment from the symptoms is present in

at least two settings (e.g., at school [or work] and at

home).

C. Several inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive

symptoms are present in two or more settings, (e.g.,

at home, school or work; with friends or relatives; in

other activities).

D. There must be clear evidence of clinically

significant impairment in social, academic or

occupational functioning.

D. There is clear evidence that the symptoms interfere

with, or reduce the quality of, social, school, or

work functioning.

E. The symptoms do not occur exclusively during the

course of a pervasive developmental disorder,

schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorders and is

not better accounted for by another mental disorder

(e.g., mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative

disorder, or a personality disorder).

E. The symptoms do not occur exclusively during the

course of schizophrenia or another psychotic

disorder and are not better explained by another

mental disorder (e.g., mood disorder, anxiety

disorder, dissociative disorder, personality disorder,

substance intoxication or withdrawal).

Code based on type:

314.01 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder,

Combined Type: if both Criteria A1 and A2 are met

for the past 6 months

314.00 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder,

Predominantly Inattentive Type: if Criterion A1 is

met but Criterion A2 is not met for the past 6

months

314.01 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder,

Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Type: if

Criterion A2 is met but Criterion A1 is not met for

the past 6 months

Coding note: For individuals (especially adolescents

and adults) who currently have symptoms that no

longer meet full criteria, "In Partial Remission" should

be specified.

Specify whether:

Combined presentation: If enough symptoms of

both criteria inattention and hyperactivity-

impulsivity were present for the past 6 months

Predominantly inattentive presentation: If enough

symptoms of inattention, but not hyperactivity-

impulsivity, were present for the past 6 months

Predominantly hyperactive-impulsive presentation:

If enough symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity

but not inattention were present for the past 6

months.

Specify if:

In partial remission: When full criteria were

previously met, fewer than the full criteria have

been met for the past 6 months, and the symptoms

still results in impairment in social, academic, or

occupational functioning.

20

Table 7. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Comparison (continued)

DSM-IV DSM-5

Specify current severity:

Mild: Few, if any, symptoms in excess of those

required to make the diagnosis are present, and

symptoms result in no more than minor impairments

in social or occupational functioning.

Moderate: Symptoms or functional impairment

between "mild" and "severe" are present.

Severe: Many symptoms in excess of those required

to make the diagnosis, or several symptoms that are

particularly severe, are present, or the symptoms

result in marked impairment in social or

occupational functioning.

3.2.2 Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD, under Trauma- and Stressor-Related

Disorders)

Description. DSM-5 criteria for PTSD differ significantly from those in DSM-IV for

children and adolescents. The arousal cluster will now include irritability or angry outbursts and

reckless behaviors. PTSD in the DSM-5 is more developmentally sensitive in that diagnostic

thresholds have been lowered for children and adolescents.

Separate criteria have been added for children aged 6 years or younger. These criteria

have been designed to be more developmentally appropriate for young children by including

caregiver-child–related losses as a main source of trauma and focus on behaviorally expressed

PTSD symptoms. According to the DSM-5, PTSD can develop at any age after 1 year of age.

Clinical re-experiencing can vary according to developmental stage, with young children having

frightening dreams not specific to the trauma. Young children are more likely to express

symptoms through play, and they may lack fearful reactions at the time of exposure or during re-

experiencing phenomena. It is also noted that parents may report a wide range of emotional or

behavioral changes, including a focus on imagined interventions in their play. The preschool

subtype excludes symptoms such as negative self-beliefs and blame, which are dependent on the

ability to verbalize cognitive constructs and complex emotional states. The developmental

preschool PTSD subtype lowers the Cluster C threshold from three to one symptom.

The new criteria were based on Scheeringa and colleagues' proposed alternative

algorithm, which was derived from studies performed in young children using modified DSM-IV

PTSD criteria (Scheeringa, Zeanah, & Cohen, 2011). These studies showed that children's loss of

a parent/caregiver through death, abandonment, foster care placement, and other main caregiver-

related events can be experienced as traumatic events. Given young children's need for a

parent/child relationship to feel safe, caregiver loss may be perceived as a serious threat to a

child's own safety and psychological/physical survival, which is part of the criteria defining a

traumatic event. The relevance of caregiver loss as a source of trauma also applies among older

children, since the loss of parents/caregivers is more associated with trauma than high-magnitude

events, like a motor vehicle crash. One report of children in foster care found that the most

common trauma identified by children aged 6 to12 to their therapists was ''placement in foster

21

care" (Scheeringa et al., 2011). Table 8 shows a comparison between DSM-IV and DSM-5

diagnostic criteria for PTSD.

Estimated Prevalence. Rates of PTSD in preschool children diagnosed with DSM-IV

criteria have been lower than in other age groups. This was in part related to DSM-IV language

stipulating that a child must have an intense response to the event—intense fear, helplessness, or

horror—that in children could be expressed by disorganized or agitated behavior. This language

has been deleted from the DSM-5, because the criterion proved to have no utility in predicting

the onset of PTSD and because the diagnostic criteria were not developmentally informed

(American Psychiatric Association, 2013d). With DSM-IV criteria, even in severely traumatized

young children, the frequencies of PTSD ranged only between 13 percent and 20 percent. With

the new algorithm proposed for DSM-5, 44 percent to 69 percent of children in the same studies

would be diagnosed with PTSD (Scheeringa et al., 2011).

Based on a total of 1,073 parents of children attending a large pediatric clinic that

completed the Child Behavior Checklist Age 1.5-5 Years and a new interviewer-based

psychiatric diagnostic measure (the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment), 0.1 percent of 2 to 5

year olds in one study qualified for PTSD under DSM-IV and 0.6 percent qualified with the new

algorithm proposed for DSM-5 (Egger et al., 2006). In other community studies of children 1 to

6 years old recruited after mixed-traumatic events, the estimate for PTSD was 0 to 1.7 percent

using DSM-IV criteria and 10 percent to 26 percent with the proposed DSM-5 algorithm

(Scheeringa et al., 2011).

Table 8. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Comparison Children 6 Years and

Younger

DSM-IV: PTSD DSM-5: PTSD

Disorder Class: Anxiety Disorders Disorder Class: Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

A. The person has been exposed to a traumatic

event in which both of the following were

present:

1. The person experienced, witnessed or was

confronted with an event or events that

involved actual or threatened death or

serious injury, or a threat to the physical

integrity of self or others.

2. The person's response involved intense fear,

helplessness, or horror.

Note: In children, this may be expressed instead

by disorganized or agitated behavior.

A. Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or

sexual violence in one or more of the following ways:

1. Directly experiencing the traumatic event(s).

2. Witnessing, in person, the event(s) as it occurred to

others, especially primary caregivers.

3. Learning that the traumatic event(s) occurred to a

parent or caregiving figure.

Note: Witnessing does not include events that are

witnessed only in electronic media, television, movies,

or pictures.

(continued)

22

Table 8. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Comparison Children 6 Years and

Younger (continued)

DSM-IV: PTSD DSM-5: PTSD

Disorder Class: Anxiety Disorders Disorder Class: Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

B. The traumatic event is persistently re-

experienced in one or more of the following

ways.

1. Recurrent and intrusive distressing

recollections of the event, including images

thoughts or perceptions. Note: In young

children, repetitive play may occur in which

themes or aspects of the trauma expressed.

2. Recurrent distressing dreams of the event.

Note: In children, there may be frightening

dreams without recognizable content.

3. Acting or feeling as if the traumatic event

were recurring (includes a sense of reliving

the experience, illusions, hallucinations, and

dissociative flashback episodes, including

those that occur on awakening or when

intoxicated). Note: In young children,

trauma-specific reenactment may occur.

4. Intense psychological distress at exposure to

the internal or external cues that symbolize

or resemble an aspect of the traumatic

event.

5. Physiological reactivity on exposure to

internal or external cues that symbolize or

resemble an aspect of the traumatic event.

B. Presence of one or more of the following intrusion

symptoms associated with the traumatic event(s),

beginning after the traumatic event(s) occurred:

1. Recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive distressing

memories of the traumatic event(s).

Note: Spontaneous and intrusive memories may not

necessarily appear distressing and may be expressed as

play reenactment.

2. Recurrent distressing dreams in which the content

and/or effect of the dream are related to the traumatic

event(s).

3. Dissociative reactions (e.g., flashbacks) in which the

child feels or acts as if the traumatic event(s) were

recurring. (Such reactions may occur on a

continuum, with the most extreme expression being a

complete loss of awareness of present surroundings.)

Such trauma reenactment may occur in play.

4. Intense or prolonged psychological distress at

exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize

or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s).

5. Marked psychological reactions to reminders of the

traumatic event(s).

C. Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with

the trauma and the numbing of general

responsiveness (not present before trauma), as

indicated by three or more of the following:

1. Efforts to avoid thoughts, feelings, or

conversations associated with the trauma.

2. Efforts to avoid the activities, places, or

people that arouse recollections of the

trauma.

3. Inability to recall important aspect of the

trauma.

4. Markedly diminished interest or

participation in significant activities.

5. Feelings of detachment or estrangement

from others.

6. Restricted range of affect (e.g., unable to

have loving feelings).

7. Sense of a foreshortened future (e.g., does

not expect to have a career, marriage,

children, or a normal life span).

C. One or more of the following symptoms, representing

either persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the

traumatic event(s), or negative alterations in cognitions

and mood associated with the traumatic event, must be

present, beginning after the traumatic event(s) or

worsening after the event.

Persistent avoidance of stimuli

1. Avoidance of or efforts to avoid places or physical

reminders that arouse recollections of the traumatic

event(s).

2. Avoidance of or efforts to avoid people,

conversations, or interpersonal situations that arouse

recollections of the traumatic event(s).

Negative alterations in cognitions

3. Substantially increased frequency of negative

emotional states (e.g., fear, guilt, sadness, shame,

confusion).

4. Markedly diminished interest or participation in

significant activities, including constriction play

5. Social withdrawn behavior

6. Persistent reduction in expression of positive

emotions.

(continued)

23

Table 8. DSM-IV to DSM-5 Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Comparison Children 6 Years and

Younger (continued)

DSM-IV: PTSD DSM-5: PTSD

Disorder Class: Anxiety Disorders Disorder Class: Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

D. Persistent symptoms of increased arousal (not

present before the trauma), as indicated by two

or more of the following:

1. Difficulty falling or staying asleep

2. Irritability or outbursts of anger

3. Difficulty concentrating

4. Hyper vigilance

5. Exaggerated startle response

D. Alterations in arousal and reactivity associated with the

traumatic event(s), beginning or worsening after the

traumatic event(s) occurred, as evidence by two (or

more) of the following:

5. Sleep disturbance (e.g., difficulty falling or staying

asleep or restless sleep).

1. Irritable behavior and angry outbursts (with little or

no provocation) typically expressed as verbal or

physical aggression toward people or objects

(including extreme temper tantrums).

4. Problems with concentration.

2. Hyper-vigilance.

3. Exaggerated startle response.

E. Duration of the disturbance (symptoms in

criteria B, C, and D) is more than 1 month.

E. Duration of the disturbance is more than 1 month.

F. The disturbance causes clinically significant