“What Matters” to

Older Adults?

A Toolkit for Health Systems to Design

Better Care with Older Adults

This content was created especially for:

TOOLKIT

An initiative of The John A. Hartford Foundation and

the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in

partnership w ith the American Hospital Association

(AHA) and the Catholic Health Association of the

United States (CHA).

Authors:

Mara Laderman, MSPH: Director, IHI

Clark Jackson, MPH: Research Associate, IHI

Kevin Little, PhD: Principal, Informing Ecological Design, LLC, and IHI Faculty

Tam Duong, MSPH: Senior Project Manager and Research Associate, IHI

Leslie Pelton, MPA: Senior Director, IHI

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by a grant from The SCAN Foundation. The SCAN Foundation works to

advance a coordinated and easily navigated system of high-quality services for older adults that

preserve dignity and independence. For more information, visit www.TheSCANFoundation.org.

This work was also made possible by The John A. Hartford Foundation, a private, nonpartisan,

national philanthropy dedicated to improving the care of older adults. For more information, visit

www.johnahartford.org.

IHI would like to thank our partners, the American Hospital Association (AHA) and the Catholic

Health Association of the United States (CHA), for their leadership and support of the Age-

Friendly Health Systems initiative. Learn more at ihi.org/AgeFriendly.

We would also like to thank the following individuals who provided guidance and critical review

through the development of this toolkit: Gretchen Alkema, Lil Banchero, Len Barry, Kevin Biese,

Maureen Bisognano, Susan Block, Joan Chaya, Lenise Cummings-Vaughn, Claire Curtis, Kate

DeBartolo, Susan Edgman-Levitan, Lindsay Gainer, Damara Gutnick, Daniela Lamas, Jennifer

Liu, Catherine Mather, Kelly McCutcheon Adams, VJ Periyakoil, Pat Rutherford, Lauge Sokol-

Hessner, Mary Tinetti, Matthew Tremblay, Erin Westphal, and Angela Zambeaux. Thank you to

the five prototype health systems — Anne Arundel Medical System, Ascension, Kaiser Permanente,

Providence St. Joseph, and Trinity — for stepping forward to learn what it takes to become an Age-

Friendly Health System. Finally, our deepest gratitude to Pat McTiernan and Val Weber of IHI for

their support in editing this toolkit. The authors assume full responsibility for any errors or

misrepresentations.

For more than 25 years, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has used improvement science to advance and sustain better outcomes in health

and health systems across the world. We bring awareness of safety and quality to millions, accelerate learning and the systematic improvement of care,

develop solutions to previously intractable challenges, and mobilize health systems, communities, regions, and nations to red uce harm and deaths. We

work in collaboration with the growing IHI community to spark bold, inventive ways to improve the health of individuals and populations. We generate

optimism, harvest fresh ideas, and support anyone, anywhere who wants to profoundly change health and health care for the bet ter. Learn more at ihi.org.

Copyright © 2019 Institute for Healthcare Improvement. All rights reserved. Individuals may photocopy these materials for educational, not -for-profit uses, provided that the

contents are not altered in any way and that proper attribution is given to IHI as the source of the content. These materials may not be reproduced for commercial, for -profit

use i n any form or by any means, or republished under any circumstances, without the written permission of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 3

Contents

“What Matters” to Older Adults: The Basis of Age-Friendly Health Care 4

The Age-Friendly Health Systems Initiative 6

Important Considerations for “What Matters” Conversations 8

Who Should Initiate a “What Matters” Conversation 11

What to Discuss in a “What Matters” Conversation 12

How to Prepare Older Adults and Caregivers for a “What Matters” Conversation 14

How to Conduct an Effective “What Matters” Conversation 15

Documenting “What Matters” Information 18

Incorporating “What Matters” Information into the Care Plan 21

Measuring “What Matters” 22

Conclusion 26

Case Examples 27

Appendix A: Resources to Support “What Matters” 29

Conversations with Older Adults

Appendix B: Examples of “What Matters” Conversations 31

Appendix C: Detailed Information on “What Matters” 32

Process and Outcome Measures

Appendix D: A Multicultural Tool for Getting to Know

You and What Matters to You 36

References 38

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 4

“What Matters” to Older Adults: The Basis

of Age-Friendly Health Care

In March 2012, Michael Barry, MD, and Susan Edgman-Levitan, PA, introduced the concept of

asking patients “What matters to you?” in addition to asking “What is the matter?” Their goal was

to increase providers’ awareness of critical issues in their patients’ lives that could drive

customized plans of care. Since then, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and other

organizations around the world have been encouraging providers and health care organizations to

ask patients and their caregivers about “What Matters” to them to inform their care.

1

IHI’s past work on The Conversation Project

2

and Conversation Ready

3

has sought to encourage

individuals, families, and health systems to have conversations about “What Matters” in the

context of end-of-life care. The Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative builds upon IHI’s previous

work in shared decision making, expanding the asking of “What Matters” beyond the context of

end-of-life care to all care with older adults across their lifespan. “What Matters” is the foundation

of the Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative, which in its entirety encompasses four evidence-

based elements of care for older adults — What Matters, Medication, Mentation, and Mobility.

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 5

• The Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative defines “What Matters” as knowing and aligning

care with each older adult’s specific health outcome goals and care preferences including,

but not limited to, end-of-life care, and across settings of care.

• Health outcome goals relate to the values and activities that matter most to an individual,

help motivate the individual to sustain and improve health, and could be impacted by a

decline in health — for example, babysitting a grandchild, walking with friends in the

morning, or volunteering in the community. When identified in a specific, actionable, and

reliable manner, patients’ health outcome goals can guide decision making.

• Care preferences include the health care activities (e.g., medications, self-management tasks,

health care visits, testing, and procedures) that patients are willing and able (or not willing or

able) to do or receive.

The aim is to align care and decisions with the older adult’s health outcome goals.

Within the Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative, the “What Matters” element ensures ongoing

communication and relationship building with older adults and their caregivers. Instead of one-

time conversations between older adults and clinicians, “What Matters” conversations should take

place at multiple points of care (e.g., annual visits, major life events, or changes in health status)

and be coordinated among all members of the care team.

Operationalizing a system to understand, document, and act on “What Matters” to older adults in

health care organizations requires organizational culture change as well as clinician training and

specific changes to workflows and the electronic health record. “What Matters” is of great

importance to older adults, caregivers, and the health care workforce.

Note that aligning care to each patient is still a relatively new concept, particularly for patients who

are not seriously ill or near the end of life. This toolkit brings together the best available evidence

from health systems around the world to help guide the testing and implementation of this

important concept in your local health system.

The toolkit is intended to serve as a resource for multidisciplinary care teams, including, but

not limited to, physicians, nurses, physician assistants, medical assistants, social workers,

chaplains, nurse navigators, community health workers, and trained volunteers. The toolkit

provides actionable steps and guidance to ensure that every older adult’s health outcome goals

and care preferences are understood, documented, and integrated into their care by the entire

health care team.

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 6

The Age-Friendly Health Systems Initiative

What Are Age-Friendly Health Systems and Why Are

They Important?

Three factors that impact caring for older adults in the United States today are occurring

simultaneously. Together, the factors make a compelling case for health systems to better support

the needs of older adults and caregivers:

• Demography: The number of adults over the age of 65 years is projected to double over the

next 25 years.

• Complexity: Approximately 80 percent of older adults have at least one chronic condition,

and 77 percent have at least two.

• Disproportionate Harm: Older adults have higher rates of health care utilization as

compared to other age groups and experience higher rates of health-care-related harm, delay,

and discoordination.

Becoming an Age-Friendly Health System entails reliably providing a set of specific, evidence-

based best practice interventions to all older adults, as needed, in your health system. This is

achieved primarily through redeploying existing health system resources to achieve:

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 7

• Better health outcomes for this population

• Reduced waste associated with low-quality, unwanted, or unneeded services

• Increased utilization of cost-effective services for older adults

• Improved reputation and market share with a rapidly growing population of older adults

The “4Ms” Framework of an Age-Friendly Health System

In 2017, The John A. Hartford Foundation and IHI, in partnership with the American Hospital

Association (AHA) and the Catholic Health Association of the United States (CHA), launched the

Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative, which set the bold aim that 20 percent of US hospitals and

health systems would be Age-Friendly Health Systems by December 2020.

The 4Ms Framework that emerged from the Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative is both

evidence-based and able to be put into practice reliably in the health care setting. The 4Ms are:

• What Matters: Know and align care with each older adult’s specific health outcome goals

and care preferences including, but not limited to, end-of-life care, and across settings of care.

• Medication: If medication is necessary, use age-friendly medication that does not interfere

with What Matters to the older adult, Mentation, or Mobility across settings of care.

• Mentation: Prevent, identify, treat, and manage dementia, depression, and delirium across

settings of care.

• Mobility: Ensure that older adults move safely every day in order to maintain function and

do What Matters.

The 4Ms are the essential elements of high-quality care for older adults and, when implemented

together, indicate a broad shift by health systems to focus on the needs of older adults. Reliable

implementation of the 4Ms is supported by board and executive commitment to becoming an Age-

Friendly Health System, engagement of older adults and caregivers, and community partnerships.

“What Matters” as the Basis of Age-Friendly Care

In the Age-Friendly Health Systems initiative, “What Matters” to the older adult is the basis for the

relationship with the care team and shapes the care that is provided. “What Matters” integrates

care and decision making across care settings. “What Matters” is not limited to end-of-life

planning. It is therefore essential to the older adult, the care team, and the health system that

“What Matters” to each older adult is identified, understood, and documented so it can be acted

upon, and updated across settings of care following changes in care or life events.

While fundamental to person-centered care, the practice of “What Matters” is the least developed

of the 4Ms. Because of its importance, and the need for further development in practice, this “What

Matters” to Older Adults Toolkit was developed by IHI with support from The SCAN Foundation.

Bringing together the best available evidence from health systems around the world, the toolkit is a

starting place and an invitation to learn together how to better understand and act upon “What

Matters” to older adults and measure progress in doing so.

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 8

Important Considerations for “What Matters”

Conversations

Understanding “What Matters” is an ongoing process, built on strong relationships between care

team members and older adults. While there are some critical moments when an older adult’s

health and care goals and preferences may need to be elicited or redefined, understanding “What

Matters” requires a series of conversations over time that become the guide for how care is

delivered. There two considerations for “What Matters” conversations, as described below.

1. “What Matters” Conversations at Certain Care Touchpoints

Care touchpoints for older adults such as regular visits, annual wellness visits, a new diagnosis, a

life-stage change, ongoing chronic disease management, and inpatient visits present opportunities

for “What Matters” conversations (see Figure 1). These types of care interactions tend to be time

limited and specific to a clinical interaction. “What Matters” conversations can and should take

place in various settings, including inpatient hospital, primary care, cancer care, skilled nursing

facility or nursing home, home-based care, and specialty services such as rehabilitation.

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 9

Figure 1. Care Touchpoints When “What Matters” Conversations Might Occur

Note that asking older adults about “What Matters” can be difficult in the emergency department

(ED), when decisions need to be made quickly to address the urgent issue at hand. Rather than

initiating “What Matters” conversations in the ED setting, ED care teams are more likely

“customers” of this information, using it to guide care decisions, particularly as patients in the ED

may not be able to communicate their goals and preferences during an emergency encounter.

Documenting “What Matters” information consistently and making it easily and clearly accessible

to clinicians in all settings are the most important factors in ensuring patients’ “What Matters”

preferences are known and respected in the ED.

2. “What Matters” Conversations as Part of Routine and

Recurring Care

Consistently incorporating “What Matters” as part of discussions between older adults and

clinicians is a key part of relationship-based care. These conversations might be broad (e.g., “My

grandchildren and knitting are important to me”) or specific (e.g., “I am worried I will be too weak

to attend a family reunion I’ve been looking forward to next month”).

“What Matters” conversations may be more effective and actionable if anchored to something

the older adult cares about, by connecting their goals and preferences to the impacts of care

and care decisions. “What Matters” conversations must also take into consideration cognition,

health status, and identity.

• A longer annual w ellness visit can be conducive to an initial “What Matters”

conversation. Regular w ellness visits are also an excellent opportunity to continue

“What Matters” conversations over time.

Regular and Annual Wellness Visits

• Schedule an initial “What Matters” conversation one w eek after the older adult has

received a new diagnosis or change in health status, and use this information w hen

planning a course of care.

New Diagnosis or Change in Health Status

• Initiate a “What Matters” conversation during a primary care appointment w ith an

older adult w ho has just entered retirement or enrolled in Medicare. Review “What

Matters” information at each visit follow ing the life-stage change for any updates on

the older adult’s care.

Life-Stage Change

• Discuss “What Matters” during primary care visits, revisiting past conversations and

discussing any changes or updates to the older adult’s goals and preferences.

Chronic Disease Management

• Ask older adults w hat is important to them at every hospitalization and document any

new information.

InpatientVisits (hospital, nursing home, skilled nursing facility)

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 10

Cognition

The care team must consider how older adults’ cognitive status does, and does not, impact their

ability to engage in meaningful conversations about their goals and preferences. Some clinicians

may think an older adult with cognitive impairment is not capable of a “What Matters”

conversation, and thus will not introduce the opportunity or will only speak with the family

or caregiver.

Older adults living with cognitive impairment and dementia are often capable of expressing their

goals and preferences and should participate in “What Matters” conversations to the degree

possible. It is the care team’s responsibility to get to know each older adult and engage with him or

her directly. Careful consideration should be given to the timing of “What Matters” conversations.

There may be times of the day when the older adult is more lucid (e.g., earlier in the day). If there

is significant cognitive impairment, the most important aspect of “What Matters” may be finding

out who the older adult relies most on to help make decisions. The guiding principle is to maximize

autonomy of cognitively impaired older adults and not diminish their self-image (e.g., “changes in

cognition” versus “cognitive impairment”).

4

Health Status

Older adults’ goals and preferences will likely change over time as health status changes. What

matters most to someone who is functionally independent and has few health problems will differ

from someone with functional disabilities and a heavy disease burden. Accordingly, the “What

Matters” conversations to understand older adults’ goals and preferences may need to vary based

on health status.

Identity

It is critical to consider the impact of race, ethnicity, language, religion, culture, and other

identities on how older adults view health and illness, and their preferences and willingness to

engage in conversations about “What Matters.” Issues of trust between some populations (e.g.,

communities of color, the LGBTQ+ community) and the health care system, borne of past

experiences and historic mistreatment, can affect “What Matters” conversations.

Clinicians are also at risk of expressing their own unconscious biases, which may manifest in subtle

verbal and nonverbal ways that can alienate patients. Without trust, it is challenging to truly

understand “What Matters” to inform a treatment plan that incorporates the older adult’s goals

and care preferences.

“What Matters” conversations can open the door to more culturally competent, affirming, and

humble care, as clinicians become better informed about the life and cultural contexts of each older

adult. We recommend that all clinicians undergo training on implicit bias as part of their

preparation for having “What Matters” conversations, using tools like the Project Implicit

assessments

5

and the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services

(CLAS) in Health and Health Care.

6

Guidelines from cross-cultural care can help the care team

hav e more successful conversations with older adults from different cultural backgrounds.

7

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 11

Checklist for Culturally Appropriate “What Matters” Conversations

Learn the older adult’s preferred term for his or her cultural identity.

Determine the appropriate degree of formality. Learn the older adult’s preference for how he

or she would like to be addressed and use this title and the surname (e.g., Mrs. Smith), unless

a less formal address is requested.

Determine the older adult’s preferred language. If the older adult has basic or below basic

literacy or English language proficiency, seek permission from the person to have a medical

interpreter assist in the “What Matters” conversation, or determine if a trusted individual

who is literate can be present during the “What Matters” conversation.

Be respectful of nonverbal communication. Watch for body language cues that might be

linked to cultural norms. Adopt conservative body language, use a calm demeanor, and avoid

expressive gestures.

Address issues linked to culture such as a lack of trust, fear of medical experimentation, fear

of side effects, and unfamiliarity with Western biomedical belief systems.

Rev iew the medical records to determine if there has been a history of trauma, including

refugee status, survivors of violence, genocide, and torture. These are v ery sensitive issues

and must be approached with caution. Reassure the older adult of the confidentiality of the

clinician–patient relationship.

Determine the level of acculturation and recognize that this is a factor for individuals who are

recent immigrants, as well as for those who are not recent immigrants.

Recognize health beliefs that include the use of alternative therapies.

Consider how gender or gender identity might affect decision making.

Consider an approach to decision making that recognizes family and community decisions

and does not automatically exclude them in favor of individual autonomy.

Who Should Initiate a “What Matters”

Conversation

Any member of the care team can initiate and document a conversation with an older adult about

their goals and preferences:

• While physicians may be the default care team member guiding care decisions based on an

older adult’s goals and preferences, they may not have time or the communication skills

necessary to engage in these conversations during a visit.

• Nurses, physician assistants, social workers, and medical assistants may have a close

relationship with the older adult and have more time for “What Matters” conversations.

Chaplains, nurse navigators, community health workers, or trained volunteers may also be

able to have meaningful conversations about goals and preferences and record that

information for clinicians to access.

• “What Matters” can also be elicited by self-report (for example, a form sent to an older adult

prior to the annual wellness v isit or filled out while in the waiting room).

Because “What Matters” conversations should be part of an ongoing dialogue, several members of

the interdisciplinary care team may have conversations with the older adult about his or her goals

and preferences at different times (for example, an older adult’s general values preferences may

remain relatively static over time, but specific goals may change from visit to visit). We recommend

that all members of the care team undergo training on motivational interviewing and shared

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 12

decision making prior to engaging in “What Matters” conversations (see Appendix A: Resources to

Support “What Matters” Conversations with Older Adults for additional resources).

Regardless of who on the care team conducts the “What Matters” conversation, there should be

a clear process for documenting and sharing this information. It is important to document and

communicate the older adult’s exact words, as these can be the most impactful. The documentation

process might include a write-in template (see Appendix D for one example), detailed notes in

the electronic health record (EHR) with information on health goals and care preferences, or

(for inpatients) a whiteboard in an older adult’s room that is updated with “What Matters” to

them daily. Whichever method is used, every care team member needs to be trained on where

to record their “What Matters” conversations, and where to find documentation of previous

“What Matters” conversations.

What to Discuss in a “What Matters”

Conversation

“What Matters” conversations are more effective and actionable if they: 1 ) explore the older adult’s

life context, priorities, and preferences and connect them to the impacts of care, self-management,

and care decisions; and 2) are anchored to tangible health or care events in an older adult’s life. It

may be appropriate to have an initial conversation in an outpatient setting that is focused on

understanding an individual older adult’s life context, then follow up with treatment-specific

questions or start a conversation from a diagnosis and specific treatment decisions, and then

broaden the discussion to the older adult’s life preferences.

8

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 13

Understanding Life Context and Priorities

These broad conversations explore what is important to older adults in their lives outside of their

health (e.g., children, family, pets, hobbies), both overall and on the day of the conversation.

Questions should ideally be asked by a variety of health care clinicians in their everyday

interactions with older adults in different settings.

Guiding Questions: Understanding Life Context and Priorities

• What is important to you today?

• What brings you joy? What makes you happy? What makes life worth living?

• What do you worry about?

• What are some goals you hope to achieve in the next six months or before your

next birthday?

• What would make tomorrow a really great day for you?

• What else would you like us to know about you?

• How do you learn best? For example, listening to someone, reading materials,

watching a video.

Anchoring Treatment in Goals and Preferences

“What Matters” conversations are anchored to an older adult’s health status and care needs and

may be most appropriate when there is a new diagnosis, treatment decision, or change in health

status. Questions need to focus on how treatment could facilitate or impede his or her ability to do

the things they enjoy (e.g., walking, cooking, everyday activities) or attain certain life goals (e.g.,

attending a meaningful event). Questions also should focus on a specific time frame, such as six

months or by the next birthday.

Guiding Questions: Anchoring Treatment in Goals and Preferences

• What is the one thing about your health care you most want to focus on so that you can

do [fill in desired activity] more often or more easily?

• What are your most important goals now and as you think about the future with

your health?

• What concerns you most when you think about your health and health care in the future?

• What are your fears or concerns for your family?

• What are your most important goals if your health situation worsens?

• What things about your health care do you think aren’t helping you and you find too

bothersome or difficult?

• Is there anyone who should be part of this conversation with us?

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 14

How to Prepare Older Adults and Caregivers

for a “What Matters” Conversation

Not all older adults are ready to engage in “What Matters” conversations. Most have never been

part of a discussion with a care team member beyond specific medical problems. Some older adults

and caregivers may be concerned that the questions, which are often associated with end-of-life

care, indicate a dire prognosis and spark concern that they may be terminally ill. Some may find

the questions intrusive or are reluctant, unprepared, or embarrassed to share details about their

liv es that they deem unrelated to their health care, or they are looking for more didactic

instructions. Others are willing and eager to guide clinical conversations with their nonclinical

goals. The success of being able to understand “What Matters” to each older adult will depend on

their (and their clinician’s) comfort, readiness, and expectation for incorporating their expressed

goals and preferences into care planning.

One way to prepare for “What Matters” conversations is to present the idea of identifying health

goals and care preferences prior to a face-to-face interaction with the health care system.

Conversations are likely to be more fruitful when older adults reflect in advance of a visit and have

a chance to prepare themselves to talk about their goals and priorities. Additionally, how older

adults respond to being asked depends on the framing, and the care team must be able to explain

why they are asking. Thus, setting the context for the conversation, before it happens, is critical.

Some ideas for how care team members can prepare older adults and their caregivers to have

“What Matters” conversations follow:

• Use a previsit survey, either paper or through a patient-facing EHR portal, to obtain

information about “What Matters” that is reviewed by clinicians prior to a visit.

• Meet with groups of older adults to encourage them to talk with each other about goals,

preferences, and common experiences.

• Utilize existing relationships with community-based organizations, such as faith

communities, to encourage more conversations about “What Matters.”

• Provide older adults with resources to prepare themselves to talk with their clinician, such as

the Prepare for Your Care, Stanford Medicine’s Bucket List Planner, or The Conversation

Project Starter Kits (see Appendix A for more resources).

• Include a “What Matters” brochure in waiting areas, similar to existing brochures on health

care proxies and advance care planning.

• Suggest that the older adult bring a family member, caregiver, or trusted friend to a

conversation about their goals and preferences.

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 15

How to Conduct an Effective “What Matters”

Conversation

Below is a list of tasks to complete before, during, and after a “What Matters” conversation. The

guidance generally follows the framework described in the Serious Illness Conversation Guide

from Ariadne Labs: set up the conversation, assess understanding and preferences, share

prognosis, explore key topics, and close conversations.

9

See Appendix B for examples of “What

Matters” conversations.

Before the Conversation

Prepare the older adult for the conversation in advance.

Introduce the idea of talking about “What Matters,” and ask the older adult to do some reflection

prior to the visit, including with his or her family or caregiver, if appropriate. Let the person know

that they will be asked about their goals and preferences. The care team member should explain

why this information is being sought, namely to identify what matters most to the individual so

that care can be better aligned with “What Matters.” This preparation could take place during a

prior visit or as part of previsit paperwork. For specific ideas, see the section in this toolkit on

How to Prepare Older Adults and Caregivers for a “What Matters” Conversation.

Determine who on the care team will have the conversation.

The most appropriate person to conduct the conversation may depend on the care setting and the

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 16

relationship a given care team member has with the older adult. For example, if a physician will

be working closely with the older adult to design a care plan and he or she has the time and skills

to have the discussion, it is beneficial for the physician to facilitate the “What Matters”

conversation. Alternatively, if a nurse, care manager, or other care team member spends a

significant amount of time with the older adult, then one of these people may be better positioned

to facilitate the conversation and communicate the older adult’s needs to the rest of the team.

Time and availability are also factors, which is why training all members of the care team to

facilitate “What Matters” conversations is important to sustaining this work.

Decide on a setting for the conversation.

Hav ing a “What Matters” conversation in a meeting room, sitting around a table as equals, may be

more effective than having the discussion in an exam room, since the meeting room setting can

help reduce the perceived power dynamics between the older adult and clinician. If the

conversation must take place in an exam room, the older adult and care team member should sit

in chairs facing one another, with the older adult dressed in his or her own clothes rather than in

a patient gown, if possible. If the older adult uses a hearing aid, be sure it is turned on. Home is a

good location for the discussion, if feasible. For example, it can be done by a case manager, social

worker, or homecare nurse who already v isits the older adult’s home.

Rev iew the records of previous “What Matters” conversations.

Look over notes of previous conversations about the older adult’s goals and preferences, whether

documented in the EHR or elsewhere, as they may provide a good starting point for the current

conversation and the information may need updating.

Conduct a screen for cognitive impairment to inform approach for a “What

Matters” conversation.

This screening (which should occur routinely in an Age-Friendly Health System) is critical when

preparing for a “What Matters” conversation, given the burden of cognitive impairment among

many older adults. Some potential screening tools include Ultra-Brief 2-Item Bedside Test of

Delirium;

10

naming four legged animals in one minute;

11

drawing a clock face, either in isolation

or as part of the Mini-Cog;

12

and the Short Blessed Test Months Backward Timed.

13

It is important

to bear in mind that memory deficits do not preclude capacity to make decisions about what

matters. If there is cognitive impairment, consider how the older adult’s cognitive status does,

and does not, impact his or her ability to engage in a meaningful conversation about goals and

preferences. Ask the person who they rely on most to help them make decisions and consider

windows of lucidity and timing of these conversations.

Prepare for the conversation.

If y ou will be using any handouts, prompt cards, or education tools, line them up ahead of the

conversation. If the conversation will require an interpreter, include the interpreter in any pre-

meeting team conversations to ensure that they can translate questions in a way that will be

understood by the older adult.

During the Conversation

Invite the older adult to have a conversation.

The success of a “What Matters” conversation depends on having a strong relationship between

the older adult and their care team and both parties’ having similar expectations for incorporating

nonclinical goals in care planning. Begin by asking the older adult if they would like to talk about

their goals and preferences, and (if applicable) how involved they want others to be in the

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 17

conversation. If they are not comfortable or wish for additional people to attend the conversation

(e.g., family member, caregiver), ask what would make them more comfortable and offer the

option to have the conversation at a different time.

Start by asking one or more “What Matters” questions.

See the section What to Discuss in a “What Matters” Conversation for guiding questions on how

to start a conversation. Choosing an approach depends on the purpose of the conversation and

the level of comfort the care team member and the older adult have with talking about “What

Matters.” While scripts can be helpful, many trained staff report not needing a script and prefer

tailoring a conversation based on the older adult and the context. Rather than following a script,

think about the older adult’s health status (e.g., advanced illness, single condition, multiple

chronic conditions, or generally well) and life context. See Appendix A for additional tools

and resources.

Listen carefully and ask questions.

Giv e the older adult time to think and provide answers. Ask follow-up questions as needed, but

do not ask an overwhelming number of questions. Try to ask the fewest number of questions to

obtain the information.

Use training and health literacy tools to facilitate the conversation and provide

clarification.

Being able to successfully communicate health or clinical information is a critical component

of a successful “What Matters” conversation. Once the care team member identifies the

communication method that is most comfortable for the older adult, it may be helpful to use

health literacy tools such as education videos, flash cards, or pamphlets to communicate clinical

information. Asking the older adult to explain the clinical information in their own words (the

“Teach-Back” approach) will also help confirm that the information has been effectively

communicated. Note that “Teach-Back” may not be effective for those with executive dysfunction.

Affirm the conversation for the older adult.

Throughout the conversation, the care team member should take time to 1) acknowledge the older

adult’s thoughts and feelings; 2) confirm the older adult’s understanding of what they are

communicating; and 3) ask for clarification of anything that is unclear. If the older adult has

chosen to include other people in the conversation, this can also be a time to ask whether they

need any clarification from either the clinician or the older adult.

After the Conversation

Incorporate “What Matters” information into the care plan.

Once the care team has had the “What Matters” conversation with the older adult, the next step is

to incorporate their expressed goals and preferences into their care plan. By anchoring an initial

“What Matters” conversation around specific points in the care process during which decisions

about care are likely to be made (e.g., first v isit, new diagnosis, change in health status, or life

transition), the team may be in a better position to build a clinical care plan that reflects the older

adult’s goals.

If the conversation involves clinical decision making, we recommend the following steps:

• Present personalized evidence, considering all steps above, to help the older adult

reflect on and assess the impact of care decisions regarding their goals, preferences,

and lifestyle.

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 18

• Identify choices the older adult can make and evaluate the clinical research in the

context of their life.

• Help the older adult reflect on the impact of different options on themselves and

their family.

• Come to a decision point with the older adult and family (when appropriate).

• Agree on next steps and plan for follow-up.

Document the “What Matters” conversation.

Document the conversation, ideally in the EHR, immediately following the conversation’s

conclusion, or within 24 hours. Use the person’s own words as much as possible (e.g., “Leslie

would like to be able to walk around the block” rather than “Patient wants to mobilize”) and use

tags to make preferences and goals readily searchable in the medical record (see section on

Documenting “What Matters” information for more guidance on incorporating “What Matters”

in the EHR).

Share information with the care team.

If appropriate, discuss conversation outcomes with the care team during regular team huddles.

If the team does not currently conduct regular team huddles, the Better Care Playbook provides

strategies for care teams to use huddles.

14

If any information requires immediate action, share

with appropriate care team members as soon as possible.

Continue the conversation.

During the next encounter with the older adult, revisit the previous “What Matters” conversation,

discuss any new or changing topics, and update the conversation documentation in the EHR or

the agreed upon location for storing documentation.

Documenting “What Matters” Information

Reliable and timely documentation of the older adult’s goals and preferences is a critical step in the

“What Matters” process. Documentation of the conversation should be easily accessible to the

older adult and all members of the care team so that it can be reviewed and referenced on a regular

basis and during care planning. All documented information should be clear, concise, reflective of

the older adult’s stated goals, and recorded using his or her own words as much as possible.

Where to Document “What Matters”: High-Tech and

Low-Tech Solutions

Where a care team chooses to document goals and preferences depends on available infrastructure

and care context. A whiteboard or construction paper poster can be a quick and highly visible way

to document and update “What Matters” for an older adult in an inpatient setting, but it is not

easily sharable across settings and not a practical method for documenting information in a

primary care or outpatient specialty care setting. Documenting “What Matters” in an EHR allows

clinicians to document conversations in more detail and allows the information to be reviewed over

time and by multiple members of the care team.

Both methods may be used in tandem to document both short- and long-term preferences and care

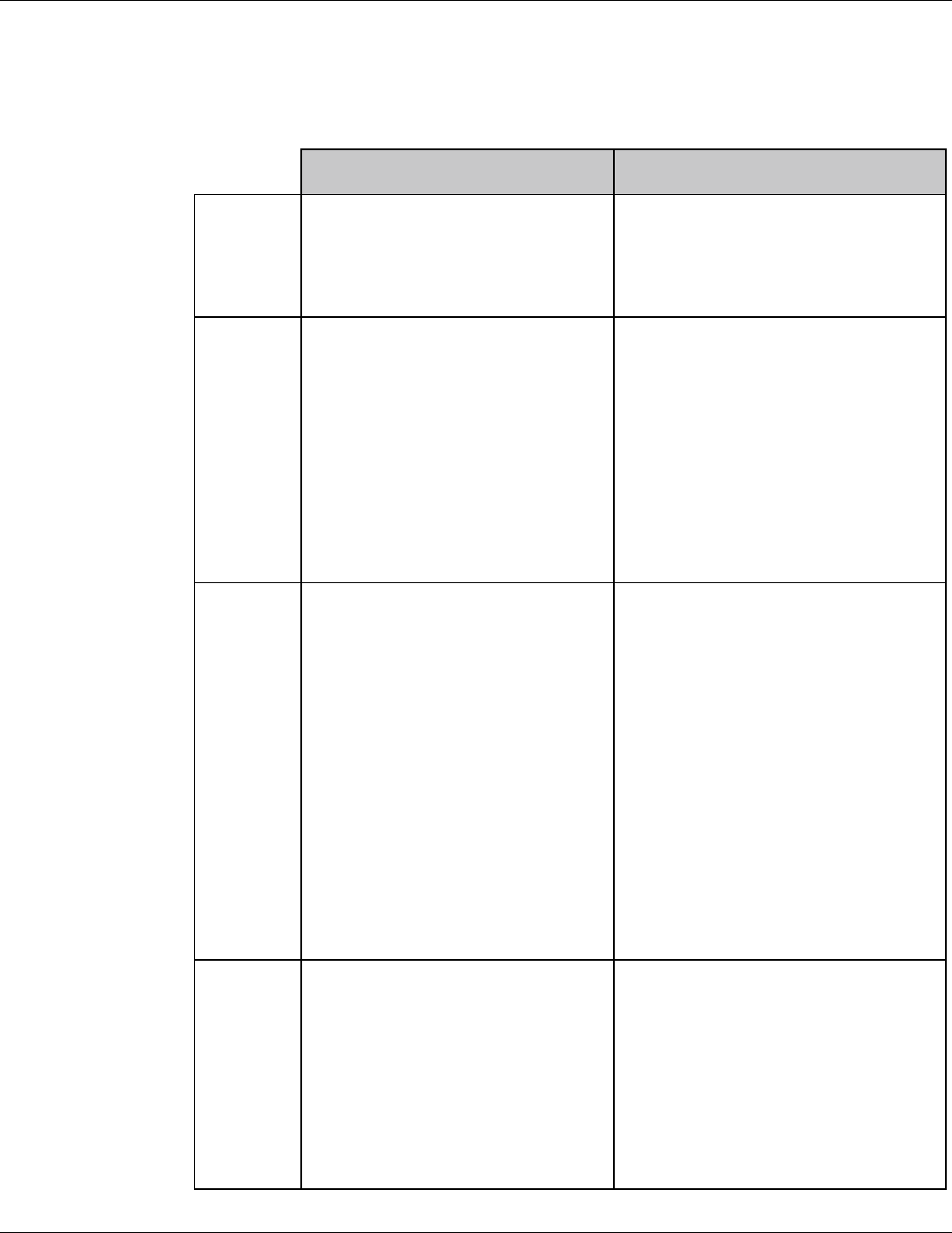

goals, depending on the care setting. Table 1 compares using physical versus electronic health

records for documentation.

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 19

T able 1. Considerations for Documenting “What Matters” Conversations in Physical

v ersus Electronic Formats

Physical Record

Electronic Health Record (EHR)

Ideal for

• Inpatient/long-term care

• Recording small amount of

information quickly (e.g., one or

two sentences)

• Inpatient and outpatient care

• Long-term recording

• Recording detailed conversations

• Sharing information across care

settings

Pros

• Low cost

• Easy and quick to document

and update

• Easily visible to any member of

care team who enters older

adult’s room

• Does not require changes to

hospital information technology

(IT) infrastructure

• Does not require significant

training resources

• Readily accessible to all members

of the care team who have access

to the EHR, regardless of location

• Can document “What Matters”

conversations over time

• Can document conversations with

more detail

• All health-related information is

stored in one centralized location

• Can link older adult’s goals and

preferences with key documents

such as advance care plan

Cons

• Not shareable across different

care settings

• Not good for documenting large

quantities of or nuanced

information

• Not easily available to members

of the care team who do not

visit older adult’s room

• Not a viable method for long-

term recording

• Not effective for outpatient or

primary care setting where

exam rooms are used by

multiple patients throughout the

day

• Not private, which could make

some older adults

uncomfortable

• Requires significant initial

investment in EHR infrastructure

modifications

• Requires care team members to

take time to enter information

• Care team members must be

trained on new processes for

documenting “What Matters” in the

EHR

Examples

• Asking a hospitalized older

adult “What matters to you

today?” during daily rounds and

documenting responses on a

whiteboard in the patient’s room

• Paper “Patient Passport”

booklet that older adult is

responsible for carrying to and

from appointments

• Creating “tags” in the EHR for all

notes that contain information on

older adults’ goals and

preferences

• Creating “flags” to remind

clinicians to update “What Matters”

information

• Documenting the older adult’s

goals in Plan of Care section of

the electronic record

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 20

Documenting “What Matters” in the Electronic Health Record

If the organization’s EHR includes a patient portal, they may want to create a module for older

adults to enter and review relevant health care proxy information, advance directives, and

important notes on their care goals. Specific guidance for different EHR vendors is challenging

giv en variability between organizations and the newness of this work. While most examples are

from organizations using Epic, the guidance for Epic could contain some applicable lessons for

other EHRs. Some suggestions follow:

• Creating tags: Tags are keywords used to link notes in EHRs and can be used to indicate

that a note contains “What Matters” information or any record of a serious illness

conversation. Once a tag has been created, Epic can be configured so that notes with specific

labels appear first in the record. This can be used to ensure that “What Matters” information

is clearly available to whoever is checking the medical record.

• Using the “Longitudinal Plan of Care” or other care planning feature: These

provide a central location for documenting “What Matters” conversations.

• Using a patient-facing portal: Many EHRs have patient-facing portals that allow patients

to directly message their clinicians, attend e-visits, and complete questionnaires remotely.

15

This tool can be used to send questionnaires about “What Matters” to older adults prior to

visits. Clinicians can then use this information to facilitate further discussion.

• Requesting a custom build: Some organizations have worked with their EHR v endors to

build a template that works for their care team. A custom-built template may include the

following sections:

○ Self-perception of health status and trajectory

○ Health and health care concerns and fears

○ Values

○ Health goals

○ Care preferences

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 21

Incorporating “What Matters” Information

into the Care Plan

Once the care team has begun the process of talking with an older adult about “What Matters” to

them, the next step is to incorporate their expressed preferences and goals into their care plan. By

anchoring an initial “What Matters” conversation around specific points in the care process during

which decisions about care are likely to be made (e.g., first visit, new diagnosis, change in health

status, or life transition), the team may be in a better position to build a clinical care plan that

reflects the older adult’s goals.

Below are some key strategies to ensure that an older adult’s expressed goals and preferences are

incorporated into their plan of care.

• Patient education as part of care planning. Because most patients are not medical

professionals, they may not be as knowledgeable about the harms and benefits of various

treatment and care options. Applicable decision aids (e.g., patient education v ideos, flash

cards) may be used to educate them and support conversations about various options and

tradeoffs in some care decisions. While such aids can be useful for relevant decisions, they are

not a substitute for a conversation to elicit the issues that are most important to older adults.

Additionally, the uncertainty of benefits and harms of treatment options for older adults

makes the traditional approach of decision aids and shared decision making less effective.

16

It

is incumbent upon the clinicians to understand each patient’s goals and preferences and offer

treatment options within the context of those goals and preferences.

• When an older adult’s preferences conflict with clinical advice. Generally, an older

adult’s goals and preferences should be respected as much as possible when planning their

care with them. However, in some cases, an older adult may have preferences that are in

direct conflict with their clinician’s medical advice, or they may reject the advice of a clinician.

If this is the case, more communication about “What Matters” to them may lead to more

clarity about why they are rejecting certain options or plans. Both the older adult and the

clinician may need to re-evaluate their perspectives and work together to find alternatives.

• Leveraging interdisciplinary resources to address older adults’ needs. When

asking older adults about “What Matters” to them, many of their preferences or concerns may

inv olve social determinants of health on which a clinician is unable to have a direct impact

(e.g., housing, food, access to social services). This is where having an interdisciplinary care

team can be critical — a social worker or nurse navigator, for example, may be able to connect

people with additional resources outside of the clinical sphere. Some teams use regular (e.g.,

weekly) interdisciplinary team huddles to discuss the results of that week’s “What Matters”

conversations and share resources that can be used to address older adults’ concerns. Sharing

these stories and problem solving together also helps build will and improve satisfaction

among members of the care team.

• Engaging with community resources. In addition to the interdisciplinary care team,

community-based organizations can be excellent resources for addressing needs beyond the

health system. Maintaining a list of community organizations that can provide support for the

social determinants of health (e.g., housing, food assistance, transportation, financial

support, behavioral health) can facilitate the provision of referrals. Documenting any referrals

giv en to an older adult during a “What Matters” conversation in the EHR also allows

clinicians to follow up on these social determinants during subsequent v isits.

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 22

Measuring “What Matters”

Why measure “What Matters”? The right measures can help improve how well the care team

understands, documents, and acts on “What Matters” to older adults. Measurement for

improvement relies on relatively frequent observations, tracked over time, to guide and maintain

changes to work.

T able 2. “What Matters” Measures

Process Measure: Documentation of “What Matters”

Why Measure Documentation of “What Matters”?

Documentation of “What Matters” signals that the care team has engaged the older adults they

serve in these conversations, and this documentation will guide the team as they develop and carry

out care plans aligned with “What Matters” for each older adult.

The process measure for “What Matters” documentation is the percent of patients served by the

relevant hospital unit or primary care team who have documentation of “What Matters” at the end

of each measurement period. Appendix C gives measurement details for inpatient and primary

care sites.

Tips for Getting Started with Measuring Documentation of “What Matters”

• Create examples. Have two care team members create or find at least three examples that

the team leaders consider to be acceptable documentation. What features do the examples

hav e that make them acceptable? Creating some good examples is a start to a formal

development of an “operational definition” to support consistent measurement.

• T est the measure.

○ Test 1: Have a care team member (a “tester”) who will be testing the measure review the

examples of good documentation. Look at one new instance of documentation. Can the

tester decide whether the documentation is acceptably aligned with the “What Matters”

questions and interaction proposed by the care team? If the tester cannot decide, what

features of documentation are missing that would enable a decision?

○ Test 2: Repeat Test 1 for five instances of documentation.

○ Test 3: Have two members of the care team assess the same three patient records for

quality of “What Matters” documentation. Compare their decisions. If two care team

members disagree on one or more decisions, discuss differences and propose changes to

the features (or criteria) that characterize good “What Matters” documentation.

Measure Type

Measure Name

Process

Documentation of “What Matters”

Outcome

Care Concordance with “What Matters”

Balancing

Impact on the Care Team

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 23

• A target goal for documentation of “What Matters” should be 95 percent or

greater. This means there is documentation showing the care team has engaged 95 percent

or more of older adults in their care in “What Matters” conversations. Remember that the

process should allow patients to decline to engage in “What Matters” conversations; an older

adult who declines to answer should be included in the numerator for this process measure.

The care team will have to assess whether the percent of older adults who decline to answer is

acceptable. If it is too high, this could be an area for study and improvement.

• Apply quality improvement methods to improve documentation. Directly observe

the documentation steps and have the care team member doing the documenting talk out

loud about the task, focusing on what is difficult or confusing. What can be changed to make

it easier to document “What Matters”? Another idea is to review 10 patient records that do

not meet the health system’s standard for documentation to identify features of poor

documentation. Then, identify one problem that can be mitigated or prevented. Test changes

to address this documentation problem.

Outcome Measure: Care Concordance with “What Matters”

Why Measure Care Concordance with “What Matters”?

While alignment between “What Matters” to older adults and the care they receive has been

studied for care at the end of life, understanding and aligning care with “What Matters” for all

older adults, regardless of life stage or prognosis, is critical.

There is currently no consensus or widely used approach to measure care concordance with “What

Matters,” though there is great interest in this topic and health systems will be actively testing and

learning how to measure concordance in the future. We know enough now to get started and learn

by doing.

The outcome measure tracks answers to closed-ended questions about care experience and “What

Matters” (see the table in Appendix C for details).

If the health system already asks specific populations about the concordance of care with “What

Matters,” then they should continue to use those tools. For example, a survey used for patients of

palliative care services at Trinity Health includes some questions that touch on concordance of care

with “What Matters,” ranked on a 1 -to-5 scale (very poor to very good). These include: 1) degree to

which the care team addressed the patient’s emotional needs; 2) the care team’s effort t o include

the patient in decisions about his or her treatment; 3) the care team’s respect of the patient’s

wishes regarding continuing or discontinuing statements.

Most hospital units and primary care practices will not yet measure care concordance with “What

Matters.” The next section introduces the collaboRATE™ tool to meet that need.

Introduction to the collaboRATE Tool

collaboRATE questions, developed by researchers at The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy &

Clinical Practice, are appropriate after a specific clinic visit or during a hospital stay.

17

• For a clinic v isit, the questions should be asked before the patient leaves the clinic.

• For a hospital stay, the questions may be asked at any time after the first day of stay when the

patient is able to communicate with the care team. Integration of collaboRATE into the

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 24

course of care during the stay or at discharge increases the number of responses (rather than

sending a post-discharge questionnaire).

• For those patients unable to communicate, there is a version designed for individuals acting

on behalf of patients.

The wording of the three questions and the appearance of the scales have been tested and should

not be varied, though the opening statement can be varied to make it appropriate for the setting.

Note that the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS)

guidelines may need to be reviewed prior to regular use of collaboRATE in hospital settings.

Getting Started with Measuring Care Concordance with “What Matters”

As collaboRATE will be a new measurement tool for most health systems, care teams will need to

figure out how to capture and summarize the question scores.

• Go to the collaboRATE Measurement Scales to find specific v ersions appropriate to your

populations (a Creative Commons license allows for free, noncommercial use).

• Consider joining the collaboRATE users group to learn more about practical use of the tool.

• Share the collaboRATE tool with relevant staff. Ask: What should we change so that almost

every patient will answer “9” to all three questions?

Outline a method to capture answers to collaboRATE and summarize top-box scores.

collaboRATE has been tested using different approaches; while response rates vary, researchers

found similar clinician performance across different data collection approaches.

18

Spreadsheet or

paper systems can suffice for initial testing and local application. REDCap software can also be

used to collect responses. Finally, health systems may want to investigate a third-party automated

solution, using existing patient portals or messaging systems, that maintains anonymity and helps

with clear reporting.

Learn about collaboRATE by testing to improve measurement. For example:

• Test collaboRATE with one patient. Ask: How will the care team member introduce the

questions? How will they record the answers?

• Test collaboRATE with five patients. What does this test indicate about collaboRATE’s

impact on workflow? What will it take to engage with patients and document answers

consistently?

• Repeat tests with older adults who prefer a language other than English.

Alternatives to Care Team Use of collaboRATE in a Hospital Setting

The collaboRATE questions and scale format, in principle, can be added to post-discharge patient

surveys administered after HCAHPS. This requires discussion with the hospital’s patient

experience survey vendor to determine if the collaboRATE questions can be included.

If it is not possible to use collaboRATE, hospitals can track the HCAHPS nurse communication

composite (HCAHPS questions 1, 2, 3) and physician communication composite (HCAHPS

questions 5, 6, 7) for patients 65 years and older who are treated in the relevant unit. Note that this

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 25

option will be of limited effectiveness if there are low counts of patients 65 years and older who are

surveyed and respond to the survey.

Additionally, hospitals can also conduct regular conversations with patients 65 years and older

about the alignment of their care with “What Matters.” A related project carried out by National

Health Service Scotland suggests five conversations a month provide a good basis to monitor

performance and provoke improvement ideas.

19

Some ideas for these conversations include:

• Ask two open-ended questions:

○ How well did we include “What Matters” to you in choosing what to do next?

○ What could we do better?

• Record the responses verbatim; don’t attempt to reword or analyze.

• Rev iew the verbatim responses with your team once a month. What ideas emerge that you

can test to improve alignment of “What Matters” with patient experience of care? Then, test

the ideas.

Balancing Measure: Impact on the Care Team

Balancing measures detect unintended consequences of a new intervention. This balancing

measure assesses the impact of “What Matters” efforts on the care team. Short term, the care team

needs to know if their approach to engaging patients and documenting “What Matters” is feasible.

Long term, the care team needs to know if engaging patients in “What Matters” conversations

causes stress, if the task of documentation creates a burden, or if follow-through into care planning

falls short. Too much stress or burden leads to inconsistent engagement in “What Matters” and can

contribute to staff burnout.

It is not necessary to create a formal survey or questionnaire to learn about work burden and

barriers to “What Matters” conversations, documentation, and use in care planning. Leaders

should instead commit to regularly asking care team members, once a month, two questions:

• What are we doing well in our “What Matters” conversations?

• What do we need to change to translate “What Matters” to our patients into more effective

care?

Tips for Getting Started

• To encourage care team members to continue to respond to the two questions, it is critical to

show that leaders are listening to their responses and acting on them. One approach is to

engage the team in testing one or more ideas and discuss together what was learned, with the

aim to make the “What Matters” work easier.

• If the question responses are collected during a team huddle or meeting and recorded on a

flipchart or whiteboard, take a digital photo so there is a time-stamped record.

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 26

Conclusion

The practice of asking “What Matters” is gaining traction around the world. Still, there remains a

gap between what care team members know about what matters to their patients and what care

patients receive in accordance with their goals and preferences. This toolkit was designed to bring

together the best available current information about how clinicians and health care organizations

can ask and act upon “What Matters” to older adults and ensure that each older adult’s health

outcome goals and care preferences are understood, captured, and integrated into their care.

Even as the number of older adults who are engaged in “What Matters” conversations increases,

this remains an area in need of additional development and testing. This toolkit is a starting place

and an invitation to learn together how to better understand and act upon “What Matters” and

measure progress in doing so. We welcome feedback and shared learnings from organizations that

are undertaking the “What Matters” work as part of their efforts to provide age-friendly care. Email

us at: AFHS@IHI.org.

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 27

Case Examples

Providence St. Joseph Health, Oregon Region

Providence St. Joseph Health, Oregon Region, began developing a process for operationalizing

“What Matters” conversations with older adults in February 2017. They initially formed an

exploratory workgroup, comprising a medical director, chaplain, physician, nurse, and social

worker. This workgroup shared their knowledge and experiences in asking “What Matters,” and

discussed what was needed to make this work valuable to patients and the organization. The

workgroup then used their shared knowledge, along with resources from the literature, “What

Matters” work at NHS Scotland, and the Serious Illness Conversation Guide to develop guidelines

for successful “What Matters” conversations.

After reviewing the first draft of the guidelines, frontline care team staff reported that the

guidelines did not provide specific enough guidance for structuring and conducting “What

Matters” conversations. The workgroup gathered comments and feedback from care teams

and created a list of suggested questions, introduced with the phrase “You can consider using the

following…” A second draft was developed and disseminated to frontline staff to begin testing

with older adults in two service lines: one primary medical home, and one elder at-home outreach

program.

Following a first round of testing with five patients, the frontline care teams debriefed their

experiences with the workgroup, who then used their feedback to revise the guidelines.

This cycle of testing is still ongoing, with the number of patients increasing each cycle. The

workgroup meets once every 2 to 3 weeks to review feedback from the frontline care teams

and revise the guidelines.

To date, the workgroup has noted the following learnings:

• Including an opening statement for clinicians to initiate “What Matters” conversations is

helpful in making clinicians and patients feel more comfortable with having a conversation.

• “What Matters” conversations have typically been shorter than clinicians anticipated.

• The guidelines have been modified to indicate that a family member or surrogate should

always be present during conversations with patients with dementia.

• Stories about rewarding experiences of “What Matters” conversations and how the

information from them is integrated into care planning is particularly motivating for frontline

team members.

Providence St. Joseph Health has also integrated “What Matters” information into their Epic EHR

sy stem using two custom-built modules (developed internally): one for advance care planning, and

one for goals.

Stanford Health Care, California

To better understand diverse patient perspectives, a team at Stanford Health Care conducted a

multisite, multilingual (English, Spanish, Burmese, Hindi, Mandarin, Tagalog, and Vietnamese)

study with the help of medical interpreters. All patients in the study uniformly reported that

discussing “What Matters” was very important to them, and a majority (60.6 percent) identified a

communication chasm between doctors and patients, and cultural/religious factors as barriers. All

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 28

were very open about expressing what mattered most to them and their goals and values if this

could be done in simple language.

In close partnership with numerous patients and family members, a simple letter template (in

a question-and-answer format) was written at a fifth-grade reading level in eight different

languages. This template was reviewed and refined based on input provided by Stanford’s Patient

Family Advisory Council (PFAC). By answering some simple questions, this template allowed

patients to share what matters most to them, their future life milestones, and wishes for care.

Patients could also choose to write a more personal “last letter” to their friends and family using

a second template.

Stanford Health Care formed an interdisciplinary team to implement the What Matters Most

(WMM) letter, including representatives from geriatrics and palliative care, blood and marrow

transplant, quality improvement, spiritual care service, nursing, patient advocacy, risk

management, legal counsel, information technology, social work, and patient care services.

A two-hour “train the trainer” training was conducted for a large group of volunteers from the

spiritual care service on how to answer questions from patients and families about the WMM letter

and how to complete the letter. Participants who attended the “train the trainer” workshop held

training sessions for multidisciplinary clinic staff, including physician assistants, advance practice

nurses, and social workers, to use the WMM letter to elicit what matters most to the patients and

to complete the letter advance directive.

A small cluster-randomized study was conducted in which the medicine ward teams were

randomized to the WMM letter arm or usual care arm. Patients admitted to the ward teams in the

WMM arm completed the letter. Patients in the usual care arm completed the traditional advance

directive. All ward care teams were given copies of their patients’ completed WMM letters (letter

arm) or advance directives (usual care arm).

For both study arms, clinician understanding of their patients’ goals of care and values was

assessed. Most clinicians preferred the WMM letter (92 percent), reporting that it: 1) improved

their understanding of the patient’s goals of care; 2) gave them more assurance in guiding the

proxy decision makers in making decisions on behalf of the patient; 3) captured end-of-life

preferences in the patient’s own words; and 4) helped clarify patient v alues and family dynamics.

Clinicians who had patients’ WMM letter (letter arm) were also more likely to know their patients’

preferred site of death (7 9 percent versus 20 percent of responses respectively, p<0.05) than

clinicians who got the advance directives (usual care arm). Clinicians reported that the WMM

letter helped them gain a better understanding of their patients’ preferences for care compared to

the traditional state-approved advance directives and the Provider Orders for Life-Sustaining

Treatment (POLST).

Patient groups have also been convened to help patients write their WMM letters in an informal

setting. One facilitator is typically needed for every 10 patients, and each session lasts

approximately 1 hour. Groups as large as 40 patients have been convened, with three to four

facilitators to help them. When conducting groups with patients with limited English proficiency, a

medical interpreter is present and sessions typically last 80 to 90 minutes.

TOOLKIT: “What Matters” to Ol der Adults? A Tool kit for Health Systems to Design Better Care with Older Adults

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

•

ihi.org 29

Appendix A: Resources to Support “What

Matters” Conversations with Older Adults

Online Tools

• Decision Worksheets (Health Decision Sciences Center, Massachusetts General Hospital):

Worksheets for diabetes, depression, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and acute low

back pain, as well as guides for using the treatment worksheets during visits

• Geritalk: Communication Skills Training for Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine Fellows

20

• Hebrew Senior Life – Vitality 360 Program: Comprehensive wellness and exercise program

offered at Orchard Cove (part of Hebrew Senior Life)

• How’s Your Health? Patient Checkup Survey: Tool for assessing patient self-confidence in

health management

• Patient Priorities Care: Resources to support aligning care with what matters most to

patients. The Specific Ask (Matters Most) Conversation Guide and the Patient Priorities

identification conversation guide help identify the values, outcome goals, and care

preferences for older adults with multiple chronic conditions

• Person-Centred Health and Care Programme (Healthcare Improvement Scotland): Practical

guidelines for person-centered health care

• Preference Based Living and the Preference for Everyday Living Inventory: Tools and

resources for assessing individual preferences for “social contact, personal development,

leisure activities, living environment, and daily routine,” both at home and in nursing homes,

including the Preferences for Everyday Living Inventory (PELI)

21

• Project Implicit (Harvard University): Tests for identifying social attitudes and implicit

associations

• Shared Decision Making National Resource Center (Mayo Clinic): Tools and resources for

clinicians to use in practicing shared decision making with patients, including patient

decision aids, trainings, and workshops

• Stanford Medicine Bucket List Planner: Tool for reflecting on core values and goals through

“bucket list” planning

• Stanford School of Medicine Ethnogeriatrics Ethno Med Website: Resources for providing

high-quality geriatrics care to a multicultural population