GENDER-RESPONSIVE

ASSESSMENT OF

BARBADOS’ SOCIAL

PROTECTION

RESPONSE TO

COVID-19

MARCH 2021

Prepared by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) as part of the United

Nations Joint Programme Enhancing Resilience and Acceleration of the Sustainable

Development Goals in the Eastern Caribbean: Universal Adaptive Social Protection.

Inspired by the Secretary General’s reform

of the United Nations, the Joint SDG Fund

supports the acceleration of progress

across all 17 Sustainable Development

Goals. We incentivize stakeholders

to transform current development

practices by breaking down silos

and implementing programmes built

on diverse partnerships, integrated

policies, strategic financing, and smart

investments. To get the 'world we want'

we need innovative solutions that

fast-track progress across multiple

development targets and results, and

contribute to increasing the scale of

sustainable investments for the SDGs and

2030 Agenda.

For more information visit us at

www.jointsdgfund.org.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. Introduction ______________________________________________________________ 1

2. Methodology ______________________________________________________________ 3

2.1 Scope of the Study _______________________________________________________________ 3

2.2 Analytical framework _____________________________________________________________ 4

3. Gender-dimension of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic _______________________ 11

3.1 The health impact _______________________________________________________________ 11

Idiosyncratic health impacts of COVID-19 _____________________________________________________ 11

Covariate health impacts of COVID-19 _______________________________________________________ 12

Age groups (elderly) ____________________________________________________________________ 12

Frontline workers (health and health sector) ________________________________________________ 12

Client-facing service sector ______________________________________________________________ 12

People in need of care __________________________________________________________________ 13

3.2 The socioeconomic impact ________________________________________________________ 14

Idiosyncratic socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 ______________________________________________ 16

Sex- and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) ___________________________________________________ 16

Early unions and early childbearing ________________________________________________________ 18

Covariate socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 ________________________________________________ 19

Poorest people and families (e.g., large families) _____________________________________________ 20

Single parents _________________________________________________________________________ 22

Tourism Sectors _______________________________________________________________________ 23

Informal sector ________________________________________________________________________ 23

Care and Domestic workers ______________________________________________________________ 24

Boys and girls in ECEC or school-age _______________________________________________________ 24

Families with children in ECEC or schooling age ______________________________________________ 25

4. Social protection before, and in response to, the COVID-19 pandemic in Barbados ____ 26

4.1 Social protection before COVID-19 _________________________________________________ 26

4.2 Social protection in response to the COVID-19 crisis ___________________________________ 29

5. A gender-responsive assessment of the social protection response to the COVID-19

pandemic. ___________________________________________________________________ 40

5.1 Targeting women and girls affected by gender-specific shocks ___________________________ 41

Women and girls at risk of SGBV ____________________________________________________________ 41

Girls at risk of early unions and childbearing ___________________________________________________ 43

Women and girls at risk of limited access to comprehensive sex-reproductive health services ___________ 44

5.2 Targeting vulnerable people affected by covariate shocks using a gender-responsive approach 44

Protecting the health of frontline workers and client-facing service workers _________________________ 45

Addressing the needs of the poorest people and families ________________________________________ 45

Supporting single parents _________________________________________________________________ 48

Sustaining the tourism sector ______________________________________________________________ 49

Safety net for people in informal employment _________________________________________________ 54

Protecting care and domestic workers _______________________________________________________ 54

Helping boys and girls who are out of school __________________________________________________ 55

Supporting families with children in ECEC and school-age ________________________________________ 56

5.3 Women's political representation __________________________________________________ 56

6. Conclusions and ways forward ______________________________________________ 57

Annex 1. Examples of the types of interventions by social protection components _________ 62

Annex 2. List of stakeholders interviewed _________________________________________ 63

Annex 3. Database of social protection response to COVID-19 in Barbados ______________ 65

Social Assistance measures in response to the COVID-19 crisis _____________________________ 65

Care Packages ___________________________________________________________________________ 65

Food vouchers __________________________________________________________________________ 65

Welfare Support _________________________________________________________________________ 65

Adopt-Our-Families Household Survival Fund __________________________________________________ 65

Adopt a Family Programme ________________________________________________________________ 66

Homes for All Programme _________________________________________________________________ 66

Payment moratorium _____________________________________________________________________ 66

Student Revolving Loan Fund (SRLF) _________________________________________________________ 66

Price freeze of a basket of essential goods ____________________________________________________ 66

Decrease in combustibles prices ____________________________________________________________ 67

Water taps reconnected __________________________________________________________________ 67

Social Care Services measures in response to the COVID-19 crisis ___________________________ 67

Helpline service for vulnerable groups during COVID-19, including women victims of domestic violence or

abuse _________________________________________________________________________________ 67

Virtual courts for cases of an urgent nature, including violence against women _______________________ 67

Strengthening of the national assistance care and shelter programmes _____________________________ 67

Social Insurance measures in response to the COVID-19 crisis ______________________________ 68

Unemployment benefits __________________________________________________________________ 68

Facilitate unemployment benefits access _____________________________________________________ 68

Business Cessation Benefits (BCB) ___________________________________________________________ 68

Anticipation of pension payments ___________________________________________________________ 68

Labour Market measures in response to the COVID-19 crisis _______________________________ 68

Barbados employment and sustainable transformation programme (BEST) __________________________ 68

Barbados Tourism Fund Facilities ___________________________________________________________ 69

Barbados Trust Fund Limited (BTFL) _________________________________________________________ 69

VAT Loan Fund __________________________________________________________________________ 69

Measures to support home care workers employed by the National Assistance Board _________________ 70

National Insurance Board __________________________________________________________________ 70

Small Business Wage Fund _________________________________________________________________ 70

Deferral of NIS contributions _______________________________________________________________ 70

Annex 4. Criteria adopted in the social protection responsive-gender assessment _________ 71

Annex 5. Adopt-a-Family Programme case studies __________________________________ 72

1

1.

Introduction

The programme "Universal Adaptive Social Protection to Enhance Resilience and Acceleration of the

Sustainable Development Goals in the Eastern Caribbean" is a joint initiative being implemented by the

United Nations (UN) in the Eastern Caribbean. The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the World

Food Programme (WFP), the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the United Nations Development

Programme (UNDP) and The United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women

(UN Women) who have come together to join forces to expand social protection towards universal access

for people and make it more adaptive to ensure they have the means to prepare before crises, including

tropical storms and hurricanes

1

and cope during, and after them.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Fund supports collaboration amongst UN agencies and other

development partners promoting a whole-of-government approach to social protection to reach those left

behind across many SDGs

. The Joint Programme, which is supported by the UN Resident Coordinator's

Office for Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean, focuses on three SDGs: poverty reduction, gender equality

and climate action. Its main objective is to strengthen people's resilience through predictable access to

adaptive and universal social protection in Barbados and Saint Lucia, as well as in the Organisation of

Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) countries.

2

The Joint Programme was necessary due to the weakness of the social protection systems in these two

countries, and their vulnerability to natural disasters, and has become critical given the unprecedented

social and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The joint SDG fund is providing US $3 million, with

an additional US $1.75 million in contributions from all partner agencies.

3

In response to the COVID-19

crisis, the joint programme adapted and enhanced its work to strengthen institutional capacity for

integrated services delivery through the development of evidence-based, gender-responsive social

protection and a disaster risk management policy and legislation, and introduce innovative financial

strategies which ensure fiscal sustainability and expanded coverage across Barbados. As part of this effort,

UNDP supports this gender-responsive assessment of the social protection system in Barbados, with a

specific focus on the response to COVID-19, to inform short, medium, and long-term shock-responsive

social protection needs within the country.

As the COVID-19 crisis will not be resolved in a few months and many countries are hit by subsequent

waves, concrete policy steps are needed to limit its dramatic socioeconomic consequences

.

4

COVID-19 is

an unprecedented public health emergency with immediate and long-term economic impacts on the

population in terms of poverty, access to food and services, unemployment, and multi-dimensional

vulnerability. It also has a strong impact on an individual's social life, interpersonal relationships, mental

health, and trust in others and institutions. The pandemic has already imposed a high cost on human lives,

but even countries without deaths related to COVID-19 have seen their economies severely harmed by the

global pandemic.

1

For example, in 2017 Hurricane Maria affected 90% of the population of Dominica in one way or another.

2

Joint SDG Fund Programme Team (2020). "Joint SDG Fund – Leave No-one Behind through Social Protection in Barbados, Saint

Lucia & the OECS", April 2020. Retrieved on 15 November 2020 from:

https://www.jointsdgfund.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/SDGfund_Factsheet_Final.pdf

3

https://jointsdgfund.org/article/un-programme-help-covid-19-response

4

https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/swift-action-can-help-developing-countries-limit-economic-harm-coronavirus

2

The COVID-19 pandemic highlights a need for Shock Responsive Social Protection (SRSP) measures that

differ from routine social protection programmes and in some respects, those usually implemented in

response to typical shocks and stressors.

COVID-19 is a rapid-onset shock which is both covariate and

idiosyncratic. When compared to previous covariate shocks, a major challenge related to COVID-19 is that

many individuals require social protection support simultaneously, and individuals who already received

support may need additional support due to the pandemic. Consequently, the capacity of the existing

system to deliver relief is typically challenged.

5

The rapid onset of the COVID-19 crisis poses specific

challenges, although similar to other rapid onset shocks (e.g., earthquake). On the other hand, the global

reach of the pandemic, as well as the unpredictability of its course and duration, make it different from

more common shocks and more comparable to global conflicts. Another peculiarity of the COVID-19 crisis

is the dramatic impact of the lockdown, and other mobility restrictions, across multiple groups with multiple

needs. The measures to contain the spread of the virus have also strongly impacted the capacity of the

government and its public services provision, further challenging the capacity of the social protection

system to respond to the needs of people affected by the crisis.

The effects of the pandemic are not gender-neutral but rather affect men, women, boys, and girls

differently because of their biological and behavioural differences, their different role in family and society,

their different needs and vulnerabilities as well as existing gender social norms, and discriminatory laws,

regulations, and practices.

Building on growing evidence on the gender-nature of the COVID-19 pandemic,

this report calls for a gender-responsive policy response to the crisis. It analyses the different impacts of

the pandemic on women, men, girls, and boys, providing evidence at global, regional, and national levels,

and highlighting how the crisis has exacerbated pre-existing gender-inequality. The report assesses the

gender-responsiveness of the SRSP measures introduced in Barbados and offers some recommendations

to strengthen the SRSP through a gender focused lens.

The report is organised into six chapters

.

Chapter 1 outlines the background of the study and highlights the need for SRSP and the commitment of

the Joint Programme to strengthen SRSP in Barbados and Saint Lucia, as well as in the Organisation of

Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) countries.

Chapter 2 discusses the scope of the study and introduces an analytical framework to assess the gender-

responsiveness of SRSP in Barbados. The nature and characteristics of the COVID-19 shocks are also

discussed in this chapter.

Chapter 3 looks at the direct and indirect impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, (i.e., health and socioeconomic

impacts), and discusses the covariate and idiosyncratic shocks of the crisis through a gender lens in relation

to both areas.

Chapter 4 discusses the social protection response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Barbados, mapping the

social protection measures introduced by the Government of Barbados in four social protection

components: social assistance, social care services, social insurance, and labour market policies. A gender-

responsive assessment of the mapped measures is offered in line with a definition of gender-responsive

policies that combine both gender-mainstreaming in the interventions and gender-specific targeted

measures.

5

Bastagli F. (2014). Responding to a crisis: the design and delivery of social protection. ODI Working Paper No.394. London:

Overseas Development Institute.

3

Chapter 5 presents a gender-responsive assessment of SRSP responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in

Barbados. It outlines recommendations to strengthen the SRSP responses for individuals at risk of

idiosyncratic impacts, with a specific focus on the need to target women and girls and covariate groups. In

doing so, it highlights how pre-crisis gender-inequality implies different risks within different gender groups

and it further highlights the need for addressing them by adopting a gender mainstreaming approach.

Finally, Chapter 6 provides short-, medium- and long-term recommendations for consideration by the

Government of Barbados to ensure a gender-responsive social protection response to the next phases of

the COVID-19 crisis and beyond.

2.

Methodology

2.1 Scope of the Study

The scope of this study is to provide a gender-responsive assessment of the social protection system in

Barbados with a specific focus on the response to COVID-19,

to inform an implementation plan for a

gender-responsive and adaptive social protection response to the pandemic.

The analysis will include:

1. The assessment of the socioeconomic impact of the pandemic with an emphasis on the differential

impacts across various groups, with a focus on women and girls;

2. A mapping of the full COVID-19 social protection response, analysing its scale and scope, identifying

critical gaps, and assessing its efficiency and effectiveness to-date;

3. A gender-responsive assessment of the social protection system response to the COVID-19

pandemic in Barbados.

The methodology used for this study relied on a desk-based literature review and a mix-methods approach

that includes both qualitative and quantitative analysis of the data.

The desk-based literature review

analysed data and publications from different sources including UN agencies, multilateral institutions,

think-tanks, Government of Barbados reports and academia. Building on a growing body of literature on

the gendered impacts of the pandemic and the need for gender-responsive measures to cope with them,

the study provides a gender-responsive assessment of the social protection response to the crisis. The

qualitative analysis builds on interviews and virtual meetings with key stakeholders to gather insights on

the impact of COVID-19 on different population groups and to map the policy responses of different

institutions. Stakeholders interviewed for this study included UN agency partners of the Joint Programme,

key government representatives, government experts and managers of social protection schemes, activists

for women's and vulnerable people rights, civil society organizations (CSOs) and beneficiaries of SRSP

interventions. The complete list of stakeholders interviewed is available in Annex 2. The quantitative

analysis was used mainly to identify groups of the population who are more vulnerable to the impact of

COVID-19 among women, men, girls, and boys in general and in categories at higher risk such as informal

workers.

4

2.2 Analytical framework

UN agencies are working together as one in the UN Social Protection Floor Initiative (SPF-I), with support

from the new UN Joint fund Window for Social Protection Floors

.

6

The Social Protection Floor is a global

effort to adopt a shared approach to ensure universal access with at least the following guarantees: access

to essential health care, including maternity care; basic income security for children (e.g., family

allowances); basic income security for people of active age who are unable to work (e.g., social protection

benefits for people with disabilities, unemployment, maternity); basic income security for elderly (e.g.,

those who receive a pension).

Social protection refers to policies and programmes aimed at preventing and protecting people against

poverty, vulnerability, and social exclusion throughout their lives.

This includes a wide range of

interventions, such as social assistance, social insurance, social care services and labour market policies to

support people's skills and access to jobs (see Box 1).

7

6

https://www.social-protection.org/gimi/ShowProject.action?id=2767

7

https://www.jointsdgfund.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/SDGfund_Factsheet_Final.pdf

5

Annex 1 is a list of possible social protection components grouped together under these four components.

Box 1.

Social Protection components

Social protection includes four components:

Social assistance

: non-contributory transfers in cash, vouchers, or in-kind (including school feeding) to

individuals or households in need; public works programmes; fee waivers (for basic health and education

services); and subsidies (e.g., for food, fuel, etc).

Social insurance

: contributory schemes providing compensatory support in the event of illness, injury,

disability, death of a spouse or partner, maternity/paternity, unemployment, old age, and shocks affecting

livestock /crops.

Social care services

: services for those facing social risks such as violence, abuse, exploitation,

discrimination, and social exclusion.

Labour market programmes

: programmes that promote labour market participation such as training,

public employment services, job creation (active labour market programmes) or those which ensure

minimum employment standards such as unemployment benefits and assistance, disability benefits,

parental leave, etc. (passive labour market programmes).

'Social assistance' and 'social insurance' together constitute 'social security', a term used by ILO and other

UN bodies interchangeably with social protection. Also 'social care services' are not often included within

the components of social protection. However, this extended definition of social protection better reflects

the type of interventions taken by the Government of Barbados in response to the COVID-19 crisis.

8

8

Carter B., Roelen K. Enfield S., and Avis W. (2019). Social Protection Topic Guide. Knowledge, evidence and learning for

development - K4D, UKaid (October 2019).

6

Social protection systems are intended to be shock responsive as they should support people in the event

of shocks or help to mitigate their exposure to shocks

.

9

Shocks are defined as events that reduce household

income, consumption, and /or accumulation of productive assets. Covariate (or aggregate) shocks, like

droughts, floods, food price increases as well as the COVID-19 pandemic, involve entire communities or

countries in systematically opposite shocks to those considered to be idiosyncratic (or unsystematic), which

affect individuals and households at the same time. In practice, covariate and idiosyncratic shocks may

interact and overlap. For instance, a regional drought, which is a covariate shock, may lead to the death of

an income-earning household member causing an idiosyncratic shock.

10

Standard social protection systems are set to respond to idiosyncratic shocks such as life cycle events such

as loss of jobs, illness, injury, maternity/paternity, death of spouse or partner etc.

These shocks, which are

experienced by individuals and households unsystematically, are typically covered by the social insurance

component of the social protection system through contributory schemes (see Box 1).

SRSPs should also respond to covariate (i.e., systematic) shocks that affect a large number of households

simultaneously

.

11

Social assistance, which typically refers to non-contributory, tax-financed or donor-

supported, social benefit schemes have proven to be effective in reducing poverty and food insecurity and

in making households more resilient to particular shocks. No systematic empirical research is available on

their effectiveness in reducing idiosyncratic shocks.

12

Women and men can be exposed to different types of risks associated with shocks and have different ways

of coping and insuring against them.

This is due to multiple factors such as biological, behavioural, and

cultural factors including persisting gender inequalities, gender roles and gender discriminatory social

norms, laws, and practices. As for idiosyncratic shocks, men and women face different risks throughout

their life cycle: mortality and morbidity risks are generally higher for men, but women and girls are at a

higher risk of malnutrition and poor health during reproductive years due to menstruation, pregnancy, and

lactation. In many countries, early marriage and early childbearing are risk factors with a high impact on

the health and development of girls, while in the labour market and the agriculture sector, women and

men are exposed to different risks and hazards.

13

Covariate shocks, even when they are not gender specific,

may affect women and men differently. This is either because one gender is over-represented in the

communities and groups of the population affected by the shock or because of pre-shock gender-

inequalities which make men and women differently able to cope with the crisis. For instance, the rise in

the price of a commodity will impact differently on women and men depending on whether they are the

major producers or consumers of that commodity.

9

Barca V (2017). Conceptualizing shock-responsive social protection. International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG), One

Pager 344, February 2017 ISSN 2318-9118.

10

Frankenberger T., Swallow K., Mueller M., Spangler T., Downen J., and Alexander S. July (2013). Feed the future learning agenda,

literature review: Improving resilience of vulnerable populations. Rockville, MD: Westat. Retrieved from:

https://agrilinks.org/sites/default/files/resource/files/Feed_the_Future_Learning_Agenda_Resilience

_Literature_Review_July_2013.pdf

11

Kind M. (2020). COVID-19 and primer on shock-responsive social protection systems, United Nations Department of Economic

and Social Affairs, Policy Brief No. 82.

12

See, for instance, World Bank (2014b). The state of social safety nets 2014. Washington D.C.: World Bank (Retrieved from:

http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/safetynets/publication/the-state-of-social-safety-nets-2014) for a review of impact

evaluations of social assistance programmes in developing countries over 1999–2009, most of which are in Latin America .

13

For a review of different risks that men and women face with implications for their health and nutritional status, see J. Harris.

2014. “Gender Implications of Poor Nutrition and Health in Agricultural Households.” In Gender in Agriculture: Closing the

Knowledge Gap, edited by A. R. Quisumbing, R. Meinzen- Dick, T. L. Raney, A. Croppenstedt, J. A. Behrman, and A. Peterman, 267–

283. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer; Rome: FAO.

7

Women and men also have different capabilities to cope with shocks and manage risks

. Having less access

to and control over assets and resources, lower access to finance and credit, and limited decision-making

compared to men, women are typically less capable than men to cope with crises. Thus, even when

covariate gender-indiscriminate shocks hit men and women equally (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic), women

are likely to suffer a higher impact because they do not have the means to cope with it. Studies show that

during a time of crisis, women suffer extensively from an increased time burden, are threatened, or become

victims of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV). They are also more likely than men to lose jobs and

assets.

14

An empirical analysis of more than 140 countries shows that natural disasters (i.e., covariate

shocks) lower the life expectancy of women more than that of men.

Even in the presence of covariate shocks, which affect entire communities, the risks to women and men

within households may be different due to gender-discriminatory social norms and practices

. While it is

well recognised that female-headed households are particularly vulnerable to the effects of shocks due to

their intrinsic characteristics, the risk of shocks may also not be shared equally by gender within households.

The intra-household literature provides evidence that household members do not pool their incomes and

the income of women and men affect household allocation decisions differently.

15

Other studies show that

in times of crisis, women act as a ‘shock absorber’ reducing their consumption to allow increased

consumption by other household members. In Indonesia, for instance, during the sharp rise in food prices

in 1997/98, mothers buffered children’s calorific intake resulting in maternal wasting and anaemia.

16

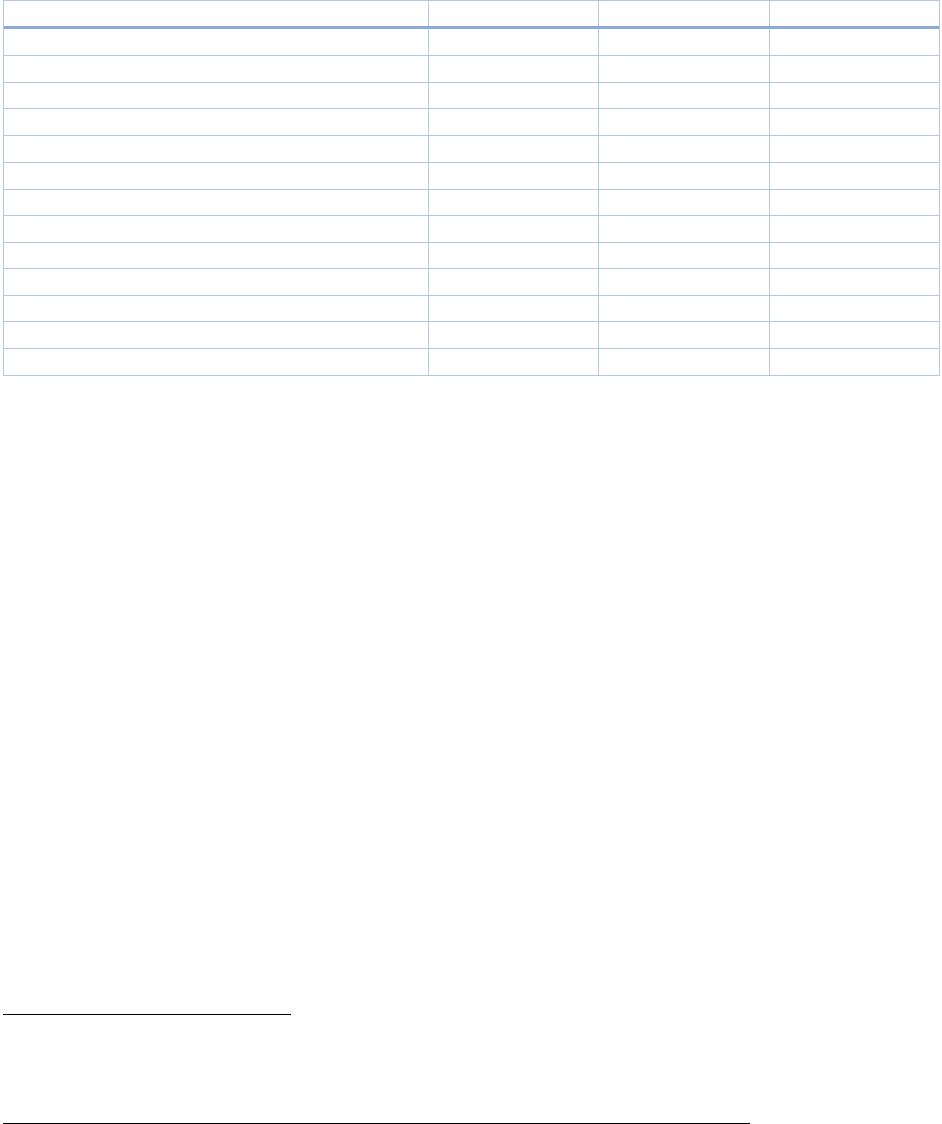

The COVID-19 pandemic is a rapid-onset covariate shock with covariate and idiosyncratic impacts.

Individuals can be affected directly, by contagion and illness (health impact), and /or indirectly, as a result

of the government-imposed lockdown and restricted movement mitigation measures when these are put

in force (socioeconomic impact). Both direct and indirect impacts can be covariate and /or idiosyncratic

(see Table 1).

The covariate impacts of COVID-19 involve specific groups of the population who are at a higher risk of

health or socioeconomic impacts.

As for the health impact, frontline workers and client-facing service

workers have a higher risk of contracting the virus as well as suffering physical and psychological

consequences for the extreme conditions of their work. Elderly people have a higher risk of severe health

consequences, and even death, due to contagion. As for the socioeconomic impact of the crisis, some

population groups are at higher risk of suffering more severe socioeconomic effects than others. This is

mainly due to the effect of specific government restrictions which affect them more than other groups and

/or the impact of their pre-existing vulnerability that limits their capacity to cope with the effect of the

crisis. These groups include poor families, people working in specific sectors such as the tourism and the

informal sectors, single parents, boys, and girls in Early Childhood Education Care (ECEC) who are of school-

age and families with children in ECEC /school age. Idiosyncratic impacts may interact, or overlap, with

covariate impacts (see Table 1).

14

Kumar N. and A. Quisumbing (2014). Gender, shocks, and resilience. Building Resilience for Food & Nutrition Security, 2020

Conference Brief 11, May 2014.

15

C. Doss. 2001. “Is Risk Fully Pooled within the Household? Evidence from Ghana.” Economic Development and Cultural Change

10:101–130.

16

Berloffa G. and F. Modena. 2009. Income Shocks, Coping Strategies and Consumption Smoothing: An Application to Indonesian

Data. Discussion Paper 1. Trento, Italy: Department of Economics, University of Trento.

8

The gender-discriminate impact of COVID-19 operates through both the impact of covariate and

idiosyncratic shocks.

Some idiosyncratic shocks are gender-specific in nature. Examples include being

victims of Sexual-Gender Based Violence (SGBV), early childbearing or getting pregnant in a time of limited

access to care services. This report discusses how the COVID-19 crisis exacerbates the risk of these gender-

specific idiosyncratic shocks. Covariate impacts may be gender-discriminate too. This happens when either

men or women are over-represented in one of the covariate groups affected by the shocks, for example, if

single parents are hit strongly by the socioeconomic impact of the pandemic and women are over-

represented among single parents then there will be an increased impact on women. The report analyses

international and national literature to highlight the status of men and women, boys and girls in the

different groups impacted by the COVID-19 shock.

Multiple factors contribute to explaining why one gender may be at a higher risk of COVID-19 idiosyncratic

and covariate impacts.

These factors include gender biological differences (e.g., female reproductive role),

gender behavioural difference (e.g., gender differences in using proper protective equipment), different

gender roles (e.g., men as main earners), and different needs and vulnerabilities (e.g., different access to

resources to cope with the effects of the crisis). Social norms and discriminatory gender practices related

to what is deemed to be appropriate for women or men, as well as laws and regulations that treat women

and men unequally, may reinforce gender inequalities and create settings in which women and girls have

different access to resources and opportunities compared to men and boys.

Table 1.

An analysis of the covariate and idiosyncratic impacts of the COVID-19 shock

COVID-19

Direct impact

(health crisis)

Groups affected by covariate

shocks

People affected by

idiosyncratic shocks

Gender

-

responsive measures

§ Age groups (elderly morbidity and

mortality)

§ Frontline workers (physical and

mental health)

§ Client-facing service sector

(physical health)

§ People in need of care (limited

access to care and services)

§ Individuals contract the

virus

§ Long term debilitation

§ Higher medical costs

Indirect impact

(socioeconomic

crisis)

Groups affected by covariate

shocks

People affected by

idiosyncratic shocks

§ Poorest people and families (no

coping mechanisms)

§ Single parents (no income

pooling, no care sharing)

§ Tourism sector (job losses, cut in

working hours)

§ Informal sector (job losses, cut in

working hours, no safety net)

§ Care and domestic workers

§ Boys and girls in ECEC/school age

§ Families with children in

ECEC/school-age (ECEC/school

closure, higher care burden

§ Job lay-off

§ Long term debilitation

§ Job loss

§ Children at home

§ Stay-at-home order

and restricted mobility

§ SGBV

§ Early childbearing

§ Early unions

§ Restricted access to

health services

including sex and

reproductive services

Source: Author’s adaptation from various sources. Gender-specific idiosyncratic shocks are in blue.

9

The scope of SRSP is to provide adequate benefits for beneficiaries of current social protection programmes

and adapt social protection to extend coverage to additional population groups to tackle the negative

effects of the crisis (adaptation).

This should be done in a comprehensive (i.e., covering all the risks) and

adequate (i.e., adequately covering the risks) manner. In doing so the existing social protection system

should not collapse (resilience).

17

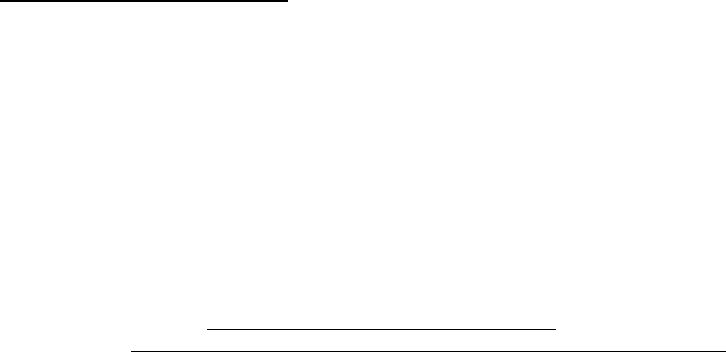

This study proposes an analytical framework for a gender-responsive social protection response to the

COVID-19 crisis

(see Figure 1) that builds on global literature around social protection and guidelines from

the UN Social Protection Floor Initiative. The framework suggests assessing the new or intensified needs

for social protection due to the COVID-19 pandemic using a gender-responsive approach that accounts for

gender based biological differences, gender based behavioural differences, differences in the roles of

women, men, girls and boys in the family and society, their different needs and vulnerabilities, as well as

gender social norms and discriminatory laws, regulations, and practices. The multidimensional aspects of

social protection require responses specifically designed to address the distinct and unique needs of the

different segments of the population, especially those who are more vulnerable, and recognising

differences between men, women, boys, and girls.

Figure 1.

Framework for a gender-responsive social protection response to the COVID-19 crisis

17

Socialprotection.org blog “Identification and registration of beneficiaries for SP- responses in the wake of COVID-19: challenges

and opportunities” by Martina Bergthaller on Tue, 09/06/2020 - 21:14

New or

intensified

needs for

social

protection

Mainstreaming gender in programming, designing and implementing policies

Gender assessment

of COVID-19 impact

Biological

differences

Different roles in

family and society

Social norms and

discriminatory

practices

Targeting

mechanisms

Gender

Categorical

Universal

Social protection

response assessment

COVERAGE

COMPREHENSIVENESS

ADEQUACY

TIMELINESS

COST-EFFECTIVENESS

ACCOUNTABILITY

SUSTAINABILITY

ACCEPTABILITY

Differences in

needs and

vulnerabilities

Behavioural

differences

Mainstreaming gender in programming, designing, and implementing policies

10

Drawing from the analysis done by the International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth

18

at a global level,

the framework indicates eight criteria to conduct the assessment of social protection responses, which are

discussed below:

Coverage

Refers to the proportion of a population who participate in a social protection

programme. The legal coverage is identified by the eligibility criteria to participate

in the programme while the effective coverage refers to the people that de facto

participate in the programme. Exclusion error (i.e., exclusion of people that are

intended to receive support) and inclusion error (i.e., inclusion of some people

who are less in need) are critical challenges of either the design or implementation

of targeted approaches.

Comprehensiveness

Looks at whether the measures in place can meet the diverse needs of different

segments of the population, or whether groups of people in need are left behind.

Adequacy

Is about adequate coverage of people's needs.

Timeliness

Is about the capacity of protecting people in a timely and predictable manner,

(i.e., before any negative coping strategy is adopted).

Cost-effectiveness

Requires making cost-effective use of all available resources for social protection

response, especially during times of crisis.

Evidence-driven

and accountability

Refers to the use of evidence ex-ante and ex-post the policy introduction. It

analyses whether the policies have been decided, designed, and implemented,

learning from the available evidence (e.g., other shocks) and whether there is any

monitoring, learning and evaluation mechanism in place to assess the effect and

sustainability of the policy.

Sustainability

Concerns the availability of knowledge, resources, and political will to ensure that

the lessons learned from social protection responses can be sustained in the long

run.

Acceptability

Refers to the extent to which beneficiaries are comfortable with the content of

the policies and how they are delivered, accounting for the characteristics of the

providers (e.g., age, sex, ethnicity, religion), the level of bureaucracy, the type of

technology involved, etc.

While this study will ideally look at all these eight criteria, in practice the analysis is limited by lack of key

data

. Existing information is complemented by in-depth interviews with key stakeholders wherever

possible. Despite difficulties in collecting a complete data set for this study, such an exhaustive framework

can guide future studies and the design of current and future social protection measures. The framework

has been derived in light of the analysis of the covariate and idiosyncratic impacts of the COVID-19 shock

to support the designing of SRSP policies that can be effective if, and when, shocks that share similar

characteristics with the COVID-19 crisis occur. The analysis of the COVID-19 shock singularities or similarities

with other shocks will inform SRSP policy and practice to enable maximum applicability in future settings.

18

https://ipcig.org/about

11

3.

Gender-dimension of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

3.1 The health impact

Since the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, almost 124 million cases and more than 2.7 million deaths have

been reported globally.

19

In February 2021, almost 20 million cases and more than 600,000 deaths from

COVID-19 were reported in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

In Barbados, from 16

March 2020 (the day of the first identified case) to 25

March 2021, there have been

3,582 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 40 deaths.

20

The low absolute number of cases and deaths needs

to be read in light of the Barbados context. Barbados has a population of 287,025 inhabitants (148,210

women and 138,815 men), of which approximately 36,000 (13%) are aged 65 or over. The elderly

population, consisting of 60 percent women, is the most vulnerable to COVID-19. This section discusses the

health idiosyncratic, and covariate impacts of COVID-19 in Barbados.

Idiosyncratic health impacts of COVID-19

A preliminary analysis of global provisional data by gender shows a similar number of confirmed cases for

men and women so far but higher mortality among men

. According to available data at the global level,

men account for a slight majority of confirmed cases (50.9%) and a higher fatality ratio (60.2%).

21

The higher mortality among males is potentially due to gender-based immunological patterns,

22

differences

in risk behaviours and social norms around masculinity. As for risk behaviours, patterns, and prevalence of

smoking, which is more prevalent among males, correlates with a higher health risk due to COVID-19.

23

Similarly, social norms around masculinity, which make men more likely to engage in risky behaviours, may

contribute to explain these figures too. For instance, some studies show that men are less prone to wear

masks, wash their hands and seek health care during the pandemic.

24

A lack of data disaggregated by gender and a lack of harmonized criteria to collect it at the country level

hinders a clear picture of the impact of COVID-19 on women's and men's health globally. Current gender

disaggregated data on the pandemic is incomplete and caution is needed when considering early

conclusions.

25

For instance, globally, only 37 percent of COVID-19 cases have been disaggregated by age

19

Data from the WHO (18 January 2021). Data retrieved from the UN Women COVID-19 and gender monitor on 15 March 20201

from: https://data.unwomen.org/resources/covid-19-and-gender-monitor

20

https://covid19.who.int/region/amro/country/bb

21

Data from the WHO (18 January 2021). Data retrieved from the UN Women COVID-19 and gender monitor on 15 March 20201

from: https://data.unwomen.org/resources/covid-19-and-gender-monitor

22

Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in

Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 2020; 395: 507–13.

23

Liu S, Zhang M, Yang L, et al. Prevalence and patterns of tobacco smoking among Chinese adult men and women: findings of

the 2010 national smoking survey. J Epidemiol Community Health 2017; 71: 154–61.

24

UN Women (2019). Progress of the World's Women 2019-2020: Families in a Changing World. New York: UN Women.

25

The Lancet (2020). "COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak", 14 March 2020. Retrieved on 7 December 2020 from:

https://www.thelancet.com/action/ showPdf?pii=S0140-6736%2820%2930526-2

12

and gender. The criteria for data collection, including deaths, has not been harmonised, thus data is not

fully comparable.

26

Covariate health impacts of COVID-19

Age groups (elderly)

Risk of severe illness, hospitalisation and even death due to COVID-19 increases with age, with older adults

being at the highest risk

. Certain medical conditions can also increase the risk of severe illness. Whilst the

largest number of cases are observed in the age group of 25 to 34 years old, followed by the oldest groups

up to 60 years old and the youngest of 20 to 24 years old, deaths are mainly associated the population of

over 50 years old, progressively raising higher for the oldest groups.

Provisional data on global deaths are higher for males for all the age-groups, but in the group of 85 years

old and over, women are over-represented.

The higher cases, and deaths, amongst women over 85 years

of age are explained by women having a greater life expectancy compared to men. The oldest women are

more vulnerable because of their advanced age. Also, in most cases they are widowed, living alone or in

long-term-care facilities and social isolation, these confinements may worsen their physical and mental

health. In some countries, long-term-care facilities have reported higher numbers of cases and deaths.

Frontline workers (health and health sector)

Frontline workers including care providers, health professionals, cleaners, and food preparation assistants,

are more exposed to contagion as well as an increased risk of suffering emotional trauma

.

27

Women are

over-represented in most of the frontline jobs

. According to ILOStat 2020

28

, globally women are 88 percent

of personal care workers, 76 percent of health associate professionals, 74 percent of cleaners and helpers,

69 percent of health professionals and 60 percent of food preparation assistants. A large share of women

is employed in the health sector as nurses, community health workers, birth attendants, pharmacy sales,

etc.

The hierarchy between nurses (mostly female) and doctors (mostly male) may undermine women's

perspective and leave them with lower protection.

During the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Nigeria, people in

lower-ranking roles (such as nurses, birth attendants, cleaners, laundry workers), most of which were

women, were not provided with the same amount of protective equipment as those with higher-ranking

roles (e.g., doctors and officials), most of which were men.

29

Client-facing service sector

Client-facing workers are exposed to frequent contacts with clients and thus they are at a higher risk of

contagion than people working in other sectors (e.g., white collar workers).

Because of occupational gender segregation, globally, women are more present in client-facing jobs while

men are more employed in logistics or security jobs

.

30

A large proportion of women are also employed in

26

UN Women (2020). Unlocking the Lockdown. The Gendered Effects of COVID-19 on achieving the SDGs in Asia and the Pacific.

Retrieved on 20 November from:

https://data.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/documents/COVID19/Unlocking_the_lockdown_UNWomen_2020.pdf

27

World Bank (2020). Gender dimensions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Policy Note. 16 April 2020.

28

https://ilostat.ilo.org/

29

Fawole, O. O. Bamiselu, P. Adewuyi, and P. Nguku. (2016). Gender Dimensions to the Ebola Outbreak in Nigeria. Annals of

African Medicine 15(1): 7-13.

30

World Bank (2020). Gender dimensions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Policy Note. 16 April 2020.

13

cleaning and sanitation services, for which demand increased during the pandemic, exposing them to a

higher risk of infection. Women are also employees in basic sectors and occupations (e.g., agriculture and

food production and distribution) that require them to work outside the home and interact with other

people during the lockdown periods.

In Barbados, a larger proportion of women than men are in the client-facing service sector but also in less

risky professional sectors.

According to the Barbados Survey of Living Condition (BSLC) 2016-17 data, 33

percent of female workers are employed in services and sales, and clerical occupations, compared to 22

percent of male workers, and 28 percent of female workers are employed in technical /associate

professional, professional, and managerial roles compared to 23 percent of male workers (see Table 3).

People in need of care

Because of the pandemic, people in need of care, including those with chronic conditions, may experience

disruptions in health service delivery, with dramatic consequences on morbidity and mortality.

While

disruption in care services due to the emergency of the pandemic should, in principle, affect men and

women equally, preliminary evidence indicates some differences between genders. In Asia and the Pacific,

for instance, 60 percent of women reported experiencing longer waiting times to see a doctor compared

to 56 percent of men.

31

More research and better data are needed to fully understand the gendered nature

of the disruption of health services during the pandemic.

The pandemic may restrict the availability of reproductive health services such as pre- and post-natal care

and women’s preventive care, which are critical to women

. According to UN Women's rapid gender

assessment surveys, in 4 out of 10 countries in Europe and Central Asia, half or more of the women in need

of family planning services have experienced major difficulty in accessing them since the start of the

pandemic.

32

Early evidence also indicates that COVID-19 has both direct and indirect effects on maternal

mortality.

33

The shift of health funds and provisions from reproductive health to pandemic response risks

has limited women's access to key reproductive health services, with a stronger impact on vulnerable

women (e.g., adolescent girls, pregnant women, women with chronic conditions).

34

In Barbados, essential health services accessed through public health centres and structures were

guaranteed during the pandemic, including critical women’s health and support services.

During the one-

month strict lockdown period, the provision of essential health services through public health centres and

structures was maintained,

35

however patients were required to make appointments before coming to

health facilities.

36

Service continuity was guaranteed also for obstetric care, antenatal check-ups and

31

UN Women (2020). Unlocking the Lockdown. The Gendered Effects of COVID-19 on achieving the SDGs in Asia and the Pacific.

Retrieved on 20 November from:

https://data.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/documents/COVID19/Unlocking_the_lockdown_UNWomen_2020.pdf

32

UN Women (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on women's and men's lives and livelihoods in Europe and Central Asia:

Preliminary results from a Rapid Gender Assessment. Bangkok: UN Women.

33

United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. "Tracking data on COVID-19 during pregnancy can protect

pregnant women and their babies." Retrieved on 7 August 2020 from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019- ncov/cases-

updates/special-populations/pregnancy-data-on-covid-19.html; and

Metz, Torri D.; Collier, C.; Hollier, Lisa M. 2020. "MPH Maternal Mortality from Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID- 19) in the

United States." Obstetrics & Gynecology 136 (2), page 313-316; and

Hantoushzadeh S. and others. 2020. "Maternal death due to COVID-19." American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 223

(109); and Roberton, T. and others. 2020. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child

mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study." Global Health 8 (7).

34

World Bank (2020). Gender dimensions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Policy Note. 16 April 2020.

35

Immunization, maternal and new-born health, sexual and reproductive health, non-communicable and communicable

diseases.

36

PAHO (2020). Barbados: An example of government leadership and regional cooperation in containing the COVID-19 virus.

14

postnatal care, essential new-born care, immunization, wellness check-ups for children, clinical care for

gender-based violence victims, sexual and reproductive health, treatment for infectious and chronic

diseases, and nutrition programmes.

37

Data for Barbados on potential changes in the quality of services or

delivery mechanisms was not available.

Moreover, people in need of care may have experienced, as other Barbadians, limited availability of key

commodities such as food, medicines, and hygiene products through retail outlets.

Respondents to the

Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security and Livelihoods Impact Survey prepared by WFP reported that in

Barbados: food, medicines and hygiene products were less available in stores than usual. A few respondents

indicated that items were completely unavailable.

38

,

39

3.2 The socioeconomic impact

The COVID-19 pandemic caused an unprecedented economic recession in Latin America and the Caribbean

(LAC), both in magnitude and duration

. The region was one of the pandemic's epicentre, reporting over a

quarter of the world´s total deaths,

40

despite hosting only 8.4 percent of the world’s population.

41

The

International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates a contraction of 9.4 percent in the regional GDP for 2020.

LAC is also the most affected region in terms of labour income loss. During the first three quarters of 2020,

labour income declined by 19.3 percent. More than 34 million workers lost their jobs in the region, although

some of them only temporarily. Job losses have not affected all segments of the population in the same

way. In every country, women and young people have suffered, in relative terms, higher job losses.

42

Despite the relatively small number of cases and deaths, Barbados is suffering a massive socioeconomic

disruption due to the slowdown in global tourism and the decline in the domestic economy.

The negative

impact of the crisis on GDP growth was particularly severe in Barbados because of the dependence of its

economy on the tourism sector, which accounts for over 40 percent of total economic activity and had

experienced a dramatic shock. In April 2020, UNDP, UNICEF, and UN Women estimated several

macroeconomic projections for different reopening scenarios for Barbados. At the time of writing this

report, the most likely scenario among those is a 5-week lockdown with tourism not reopening until the

end of 2021. This would lead to a 19 percent drop in the national GDP with a recovery of 1 percent in 2021.

In this scenario, consumption was expected to drop by 9 percent in 2020 and 3 percent in 2021 with

unemployment rising to 24 percent in 2020 and 28 percent in 2021.

43

37

A. Castro (2020). Challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic in the health of women, children, and adolescents in Latin

America and the Caribbean. UNDP LAC COVID-19 Policy Document Series No. 19.

38

The Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security and Livelihoods Impact Survey was launched by CARICOM and prepared by the World

Food Programme with support from the Food and Agriculture Organization to rapidly gather data on impacts to livelihoods, food

security and access to markets. The survey was open from 1-12 April 2020 and was shared via social media, email and media and

received 537 responses in Barbados, of which 72 percent were female. Hereafter in the report we refer to this survey as the

“2020 WFP online survey.” The survey used a web-based questionnaire, which is not representative and limits participation of

people without connectivity.

39

WFP (2020). Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security & Livelihoods Impact Survey. Barbados Summary Report. May 20202.

40

https://www.iadb.org/es/coronavirus/situacion-actual-de-la-pandemia

41

https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/

42

ILO (2020). Technical note. Labour Overview in times of COVID-19. Impact on the labour market and income in Latin America

and the Caribbean. 2

nd

edition.

43

UNDP, UNICEF, and UN Women Eastern Caribbean (2020). Barbados: COVID-19 Macroeconomic and Human Impact

Assessment Data. Retrieved on November 28 from:

https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/assessments/human_and_economic_asses

sment_of_impact_heat_-_barbados.pdf using data from https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-

COVID-19.

15

The Government proposed a five-step plan to re-open the economy, from Stage 0 before COVID-19 cases

in the country to Stage 4 with the arrival of the vaccine.

Stage 0 was before COVID-19 cases were detected

in Barbados. During this stage, Barbados adopted several measures to strengthen the institutional response

to a possible detection of COVID-19 cases in the country.

Stage 1 started on 17 March 2020 and lasted for 47 days until 3 May 2020.

It was the period with the most

restrictive measures and the higher short-term impact on people, behaviours, and the economy. With Stage

1, a limitation on mass gatherings was introduced to reduce the risk of local spread. On 28 March 2020, a

curfew from 8 P.M. to 6 A.M. with a request for limiting movement during the day was introduced. On

3April 2020, it was replaced with a 24-hour curfew with all businesses – with a few exceptions – being

required to close, including supermarkets, restaurants and government offices.

44

From 8

April 2020,

supermarkets were able to open for deliveries and curbside pickups, but customers were not allowed to

enter the supermarkets.

45

On 15 April 2020, fruit and vegetable vendors were allowed to resume

operations, and supermarkets, fish markets, hardware stores, and banks, healthcare and other essential

services, were all allowed to do business on specific days and times of the week based on the first letter of

their surnames.

46

Specific schedules were allocated to senior citizens and persons with disabilities.

47

On 20

April 2020, supermarkets and mini-markets were allowed to open longer for deliveries and curbside

pickups, and gas stations no longer fell under the alphabetic shopping schedule.

48

On 4 April 2020, the Government closed schools, which remained closed until the end of September 2020,

after which they reopened with a combination of online and face to face school for primary and secondary

students

: students attended school 2 or 3 days a week and had online school the rest of the week.

49

Learning and communication digital platforms and websites, as well as social networks, physical materials,

radio, and TV programmes, were used to offer continuity in the educational supply. Teachers were trained

to use the "G Suite for Education," a Google service for education, allowing them to maintain connections

with their students. The Ministry of Education, Technological and Vocational Training (METVT) also created

a manual and videos to support teachers and parents.

50

Barbados entered Stage 2 4 May 2020 and moved very quickly to Stage 3 18 May 2020 by progressively

relaxing some socio and economic restrictions.

51

During Stage 2, a nightly curfew replaced the 24-hours

curfew, and services of construction, manufacturing, and food production/distribution were reactivated.

During Stage 3, remaining businesses and trades reopened, but with restrictions, such as social distancing

requirements, temperature testing protocols, and limited admittance to retail spaces. In this period, the

Government started to reopen its national borders to international air traffic. However, tourism activities

had only a mild restart due to the prevailing uncertainty associated with travelling protocols and the

limitations in mobility and economic slowdown at the international level. The mandatory 14-day

quarantine, first applied to all travellers arriving from overseas, was replaced in July 2020 with screening

measures at all the country’s ports to facilitate the recovery of the tourism sector,

52

in addition to an

adjusted quarantine programme for all visitors.

44

A list of health and government services and business open during Stage 1.

45

"Guidelines for collecting groceries". Nation News. 7 April 2020. Retrieved on 7 December 2020 from:

https://www.nationnews.com/2020/04/07/guidelines-for-collecting-groceries/

46

"Shopping Schedule During COVID -19 Curfew". GIS Barbados. 11 April 2020. Retrieved on 7 December 2020.

47

"Curfew extended". Nation News. 11 April 2020. Retrieved on 7 December 2020.

48

"Government eases some restrictions under curfew". Nation News. 20 April 2020. Retrieved on 21 April 2020.

49

PAHO Office for Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean Countries. COVID-19 Situation Update No. 82. 21 September 2020.

50

https://socialdigital.iadb.org/en/covid-19/education/regional-response/6132

51

COVID-19: Management and Response Plans by Stage". Loop Barbados. 17 March 2020. Retrieved on 13 April 2020.

52

https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19

16

Since 2 January 2021, and because of a resurgence of cases and deaths related to COVID-19 in the country,

the government implemented a new nightly curfew

.

53

Schools were closed and distance learning

resumed.

54

This curfew was combined since 3 February 2021 with a lockdown during which all non-essential

businesses were closed.

55

While the lockdown was originally set until 17 February 2021, the Government

extended this to 28 February given the concerning number of cases.

With the availability of vaccines, Barbados commenced providing vaccinations on a phased approach. The

priority groups for vaccination were Barbadians over 70 years old, people with chronic diseases who were

between 18 and 69 years and frontline workers.

56

Since the start of the vaccination drive, more than 40,000

citizens received a vaccination. Barbados was one of the first Caribbean nations to take this step. Barbados

was able to secure 100,000 doses of the Oxford-Astra Zeneca (COVISHIELD) through a donation from the

Government of India, which was shared with other CARICOM neighbours.

57

The Barbados Government

subsequently negotiated the purchase of another 100,000 doses and received another batch of

vaccinations, as part of the World Health Organisation's COVAX programme.

58

On 16 March 2021, the total

number of persons who had received at least one vaccination was 54,631, of which there were 22,870

males and 31,761 females.

59

This section analyses the socioeconomic idiosyncratic and covariate impacts of COVID-19. While the

idiosyncratic impacts may be numerous and complex, this section focuses on those with a clear gender-

discrimination impact. As for the covariate socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19, the discussion points to

groups of the population that present a common risk of being exposed to the socioeconomic impact due

to the lockdowns or other restrictions imposed to contain the spread of the virus.

Idiosyncratic socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19

Sex- and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV)

A gender-specific impact emerging from the lockdown and the restricted movement strategy, as well as

economic hardship due to the crisis, was an increase in SGBV.

During the pandemic, women are at higher

risk of gender-based violence due to confinement. Emerging data and reports from the frontlines have

shown that since the outbreak of COVID-19, all types of Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG),

especially domestic violence, have intensified. In several countries, since mid-March (e.g., France,

Argentina, Cyprus, and Singapore), reports of domestic violence since the lockdown have increased to

around 30 percent.

60

Still, violence against women is widely under-reported

: previous evidence shows that less than 40 percent

of women who experienced violence reported it or sought help. Exacerbating factors include security,

health and monetary worries, cramped living conditions, isolation with abusers, movement restrictions and

deserted public spaces. Evidence indicates that, in most of the cases, health services such as domestic

violence helplines have reached capacity because access to vital sexual and reproductive services and other

53

"Covid Curfew extended". Nation News. 13 January 2021. Retrieved on 8 February 2021.

54

" Barbados to Resume School Year with Online Classes". Caribbean National Weekly. 13 January 2021. Retrieved on 8 February

2021.

55

“Barbados PM Brings Back Lockdown to Bring Rise of COVID-19 Infections Under Control”. VOA News. 27 January 2021.

Retrieved on 8 February 2021.

56

https://www.unctad15.bb/barbados-covid-19-vaccination-programme-making-good-progress/

57

Ibid

58

https://www.mondaq.com/government-public-sector/1037104/barbados-rolls-out-national-covid-19-vaccination-programme

59

https://gisbarbados.gov.bb/blog/covid-19-update-13-new-cases-31-recoveries/

60

https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/issue-brief-covid-19-and-

ending-violence-against-women-and-girls-infographic-en.pdf?la=en&vs=534

17

services such as crisis centres, shelters, legal aid and protection services were limited to prioritise COVID-

19 relief.

61

In Barbados, the level of domestic violence, especially against women and girls, continues to be a major

concern.

Gender discriminatory social norms and a male dominated culture play a key role in the

perpetuation of violence against women.

62

In 2018, the Commissioner of Police reported receiving at least

one report of domestic abuse every day. The Royal Barbados Police Force (RBPF) indicates receipt of more

than one report per day in the period 2016-2018 (see Table 2). This data is likely an underestimation of real

cases. Similarly, the higher number of cases reported by RBPF in recent years might be driven by an increase

in cases reported rather than in violence perpetrated.

Table 2.

Reports of incidents of Domestic Violence (DV), 2017-2018

Year

DV Cases

People charged

Referrals

2016

515

296

132

2017

539

289

114

2018

518

273

108

Source: Family Conflict Intervention Unit, Royal Barbados Police Force

Survey data reveal a dramatic prevalence of domestic violence, confirming that most of the cases of VAWG

remain unreported.

A study shows that more than 1 in 4 (25%) women experienced intimate domestic

violence in Barbados in 2009.

63

The BSLC 2016 data reports an estimated 24 percent of total homicides

relate to intimate partner violence.

64

In almost 9 of 10 (86.8%) reported cases of child sexual abuse reported

to the Child Care Board in 2012, the abuse is reported against girls.

The cases of DV have increased as both the effect of the lockdowns and the economic consequences of the

crisis

. The 2020 IDB online survey reported that domestic violence increased by 12.2 percent among the

household survey respondents in Barbados.

65

Despite the higher risk of becoming victims of violence for

women and children during the pandemic, there is currently only one government supported shelter for

women who are victims of gender-based violence and their children,

66

this is run by the NGO Business &

Professional Women's Club Barbados with subsidies from the Government. No government-run shelters for

women exist in the country

67

and no social protection measures were taken during the pandemic to

specifically address women at risk of gender-based violence, except a helpline service created for

vulnerable people including women victims of violence and virtual courts for urgent cases including VAWG.

61

WHO (2020). COVID-19 and violence against women. What the health sector/system can do (7

th

April 2020). Retrieved on 19

November 2020: from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331699/WHO-SRH-20.04-eng.pdf

62

Allen, C. F., and J. Maughan (2016). Barbados country gender assessment. Wildey, Barbados, Caribbean Development Bank.

63

Bureau of Gender Affairs (2009). Report on a National Study to Determine the Prevalence and Characteristics of Domestic

Violence in Barbados. Bridgetown: Caribbean Development Research Services.

64

IDB (2018). Barbados Survey of Living Conditions: 2016. Retrieved on 28

th

November 2020 from:

https://publications.iadb.org/en/barbados-survey-living-conditions-2016

65

IDB. COVID-19: the Caribbean crisis. Results from an Online Socioeconomic Survey.

66

UNDP, UNICEF, and UN Women Eastern Caribbean (2020). Barbados: COVID-19 Macroeconomic and Human Impact

Assessment Data. Retrieved on 20

th

November 2020 from: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-

COVID-19

67

IDB (2018). Barbados Survey of Living Conditions: 2016. Retrieved on 28

th

November 2020 from:

https://publications.iadb.org/en/barbados-survey-living-conditions-2016

18

Early unions and early childbearing

A critical gender-specific impact of the pandemic is an increased risk of child marriage and unions and

unwanted pregnancy

. School closures, isolation from friends and support networks, rising poverty,

economic stress, service disruptions, pregnancy, and parental deaths due to the pandemic are putting the

most vulnerable girls at increased risk of child marriage or relationships with adults. Girls that marry in

childhood face immediate and lifelong consequences to their health, education, and socioeconomic life,

which also impacts the wellbeing of their children. They are less likely to remain in school and are often

socially isolated from their own family and friends.

68

Girls who enter unions at a young age are also more

likely to experience domestic violence, abuse and forced sexual relations. Early pregnancy is one of the

most dangerous causes and consequences of these types of relationships. Young teenage girls face higher

risks of maternal mortality and morbidity and their children are more likely to be stillborn, premature,

underweight and to die in the first month of life.

69

Moreover, since pregnancy suppresses the immune

system, girls who marry early are exposed to higher health risks, including a higher vulnerability to COVID-

19.

70

In Barbados, where young girls’ relationships usually take the form of ‘visiting relationships’, the pandemic

is expected to increase the risk of early informal unions and early childbearing.

71

According to a 2017

UNICEF report, in Barbados, more than 60 percent of girls between 15 and 17 years of age who were

married or in a union were in a social and sexual relationship without habitual cohabitation.

72

,

73

In common

with other countries, in Barbados cases of early unions are expected to increase in vulnerable and poor

communities who will suffer the economic effect of the crisis. Early pregnancy can result from early

relationships as well as leading to early unions. In 2020, 50 girls aged 15-19 were pregnant per 1,000,

compared to 60 in LAC.

74

Limiting disruptions in reproductive health services is crucial in Barbados where evidence suggested low

satisfaction with modern methods of family planning even before the onset of the pandemic.

In Barbados,

the unmet need for modern contraceptive methods is a concern especially for young people, who have

restricted access to contraceptives and other sexually transmitted disease prevention services. On the

island, the minimum age for accessing health care without parental consent is 18 years

75

and there is no

68

UNICEF: https://www.unicef.org/stories/child-marriage-around-world and Plan International (2013). A girl’s right to say no to

marriage. Working to end child marriage and keep girls in school, United Kingdom.

UNFPA. Marrying too young; End child marriage. 2012. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-

pdf/MarryingTooYoung.pdf

Omoeva C, Hatch R, Sylla B. Teenage, married, and out of school. Effects of early marriage and child- birth on school dropout.

2014. Available from: http://www.ungei.org/resources/files/EPDC_ EarlyMarriage_Report.pdf

69

WHO (2011). WHO Guidelines on Preventing Early Pregnancy and Poor Reproductive Health Outcomes Among Adolescents In

Developing Countries, Geneva: WHO, 2011. See also note 8.

70

United Nations Children’s Fund, COVID-19: A threat to progress against child marriage, UNICEF, New York, 2021.

71

Based on MICS 2012 data, UNICEF estimates that in Barbados 7.7 percent of women aged 20-24 years were married or in a

union before turning 15 and 29.2 percent before turning 18. The term ‘child marriage’ is used to refer to both formal marriages

and informal unions, which includes cases in which partners live together but do not have a formal civil or religious ceremony as

well as, in the case of Barbados, informal unions with a social and sexual relationship but not cohabitation (see BSS, UNFPA, UN

Women and UNICEF (2012). Barbados Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2012).

72

UNICEF (2017). Perfil del matrimonio infatnil y les unones tempranas en América Latina y el Caribe.

73

Marriage in Barbados is regulated by the Marriage Act Chap 218 A, which prohibits forced marriage and set the minimum legal

marriage age for women and men at 18 years. However, girls between the ages of 16 and 18 may be married with the consent of

either parent, either male or female guardian, and if neither is possible, then with consent from a judge. Informal unions are not

regulated under the Marriage Act Chap 218 A but cohabitating partners who have a written agreement are entitled to certain

provision on the property, maintenance, and custody of children as well as other matters under the Family Law Act CAP 214.

74

Source: UNICEF Database

75

Allen, C. F. and J. Maughan (2016). Barbados country gender assessment. Wildey, Barbados, Caribbean Development Bank.

19

clear legal guidance for health-care workers to provide access to sexual and reproductive health services

for adolescents younger than 18 without parental consent.

76

The disruption of reproductive health services

due to the pandemic exacerbates the obstacles young people face in accessing sexual and reproductive

services, further increasing the already high rates of pre-crisis early unions with a social and sexual

relationship leading to premature childbearing.

77

Covariate socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19

The covariate impacts of COVID-19 are due to the effect of the lockdowns and restrictive measures that

affect specific segments of the population and /or those identified as being vulnerable pre-crisis that make