Stte of Helth n the EU

The Netherlnds

Countr Helth Profle 2021

2

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

The Countr Helth Profle seres

The Stte of Helth n the EU’s Countr Helth Profles

provde concse nd polc-relevnt overvew of

helth nd helth sstems n the EU/Europen Economc

Are The emphsse the prtculr chrcterstcs nd

chllenes n ech countr nst bcdrop of cross-

countr comprsons The m s to support polcmers

nd nfluencers wth mens for mutul lernn nd

voluntr exchne

The profles re the ont wor of the OECD nd the

Europen Observtor on Helth Sstems nd Polces,

n cooperton wth the Europen Commsson The tem

s rteful for the vluble comments nd suestons

provded b the Helth Sstems nd Polc Montor

networ, the OECD Helth Commttee nd the EU Expert

Group on Helth Sstems Performnce Assessment (HSPA)

Contents

1 3

2 4

3 7

4 8

5 11

51 Effectveness 11

52 Accessblt 14

53 Reslence 17

6 22

Dt nd nformton sources

The dt nd nformton n the Countr Helth Profles

re bsed mnl on ntonl offcl sttstcs provded

to Eurostt nd the OECD, whch were vldted to

ensure the hhest stndrds of dt comprblt

The sources nd methods underln these dt re

vlble n the Eurostt dtbse nd the OECD helth

dtbse Some ddtonl dt lso come from the

Insttute for Helth Metrcs nd Evluton (IHME), the

Europen Centre for Dsese Preventon nd Control

(ECDC), the Helth Behvour n School-Aed Chldren

(HBSC) surves nd the World Helth Ornzton

(WHO), s well s other ntonl sources

The clculted EU veres re wehted veres of

the 27 Member Sttes unless otherwse noted These EU

veres do not nclude Icelnd nd Norw

Ths profle ws completed n September 2021, bsed on

dt vlble t the end of Auust 2021

Demographic factors The Netherlands EU

Populton sze (md-er estmtes) 17 407 585 447 319 916

Shre of populton over e 65 (%) 195 206

Fertlt rte (2019) 16 15

Socioeconomic factors

GDP per cpt (EUR PPP) 39 641 29 801

Reltve povert rte (%, 2019) 132 165

Unemploment rte (%) 38 71

1 Numbr of chldrn born pr womn gd 15-49 2 Purchsng powr prt (PPP) s dfnd s th rt of currnc convrson tht qulss th

purchsng powr of dffrnt currncs b lmntng th dffrncs n prc lvls btwn countrs 3 Prcntg of prsons lvng wth lss thn 60 %

of mdn quvlsd dsposbl ncom Sourc Eurostt dtbs

Dsclmer The opnons expressed nd ruments emploed heren re solel those of the uthors nd do not necessrl reflect the offcl vews of

the OECD or of ts member countres, or of the Europen Observtor on Helth Sstems nd Polces or n of ts Prtners The vews expressed heren

cn n no w be ten to reflect the offcl opnon of the Europen Unon

Ths document, s well s n dt nd mp ncluded heren, re wthout preudce to the sttus of or soverent over n terrtor, to the delmtton

of nterntonl fronters nd boundres nd to the nme of n terrtor, ct or re

Addtonl dsclmers for WHO ppl

© OECD nd World Helth Ornzton (ctn s the host ornston for, nd secretrt of, the Europen Observtor on Helth Sstems nd

Polces) 2021

Demographic and socioeconomic context in The Netherlands, 2020

3

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

1 Hhlhts

Three coverage schemes provide broad health coverage to nearly all the Dutch population. These include a

competitive social health insurance system for curative care, a single-payer system for long-term care and

municipal systems for social care. Like the rest of Europe, the Netherlands faced high pressures from the

COVID-19 pandemic, and experienced a temporary drop in life expectancy in 2020. The unprecedented strain

caused by COVID-19 posed a clear challenge at all levels of the Dutch health system.

Health Status

Life expectancy in the Netherlands is higher than the EU average by about

one year, but gains have slowed over the past decade. As a result of the

COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancy fell by 0.7 years between 2019 and

2020 – the same as the EU average. Lung cancer, stroke and ischaemic

heart disease made up the highest share of mortality in 2019. In 2020, 1 in

15 deaths were attributed to COVID-19.

Risk factors

Behavioural risk factors in the Netherlands account for a lower share of

deaths than the EU average. Smoking and obesity rates are both below the

EU averages. However, one in five deaths in 2019 resulted from tobacco

consumption – a higher share than in the EU – and obesity levels among

adults have increased over the last two decades. Dutch adults and

adolescents are more physically active than those in most other EU countries.

Health system

The Netherlands spends more per capita (EUR3967) on health than the EU

average (EUR3523), with a considerable share dedicated to long-term care.

Expenditure on outpatient pharmaceuticals and medical devices is kept

low, aided by volume and price control policies and well-established health

technology assessment processes. Public sources cover a high percentage of

health expenditure, resulting in a lower share of out-of-pocket spending for

health care than the EU average.

Effectiveness

The Netherlands has among

the lowest mortality rates from

preventable and treatable causes

in the EU. Most preventable

deaths are from lung cancer,

while colorectal cancer and breast

cancer account for 40% of deaths

from treatable causes. Mortality

rates from ischaemic heart

disease, stroke and pneumonia

are among the lowest in the EU.

Accessibility

The Dutch population has

historically reported low unmet

needs for medical treatment, but

this changed during the COVID-19

pandemic when many non-urgent

services were cancelled or

postponed. Evidence suggests that

15% of people had to forgo care

during the first 12 months of the

pandemic. Teleconsultations were

used to help maintain access to

services.

Resilience

The health system response to

COVID-19 encountered obstacles,

including fragmentation in

testing, contact tracing and

vaccination efforts. After a slow

start, the vaccination campaign

accelerated, and 63% of the

population had received two

doses (or equivalent) by the end of

August 2021.

NL EU

Option 1: Life expectancy - trendline Select a country:

Option 2: Gains and losses in life expectancy

Netherlands

81

2010 2015 2019 2020

Lf xpctnc gns, rs

NL EU Lowest Hhest

Obesity

Physical

Inactivity

Smoking

0 10 20 30

70 80 90 100

0 20 40

Physical Inactivity

% of 15-yea r-olds

Obesity

% of adults

Smoking

% of adults

1

Pr cpt spndng (EUR PPP)

NL EU

Netherlands EU

€ 4 500

€

3 000

€ 1 500

€ 0

Ag-stndrdsd mortlt rt

pr 100 000 populton, 2018

Preventble

mortlt

Tretble

mortlt

Effect veness - Prevent ble nd tre t ble mort l t

AT 157 75

BE 146 71

BG 226 188

HR 239 133

CY 104 79

For tr nsl tors O

CZ 195 124

152 73

EE 253 133

FI 159 71

FR 134

63

DE 156 85

GR Greece 139 90

HU 326 176

IS 115 64

IE 132 76

IT 104 65

LV 326 196

LT 293 186

LU 130 68

MT 111 92

NL 129 65

NO 120 59

PL 222 133

PT 138 83

92

160

65

129

Netherlands EU

-

NL

EU

Shr of totl populton vccntd gnst

COVID-19 up to th nd of August 2021

SShhaarree ooff ttoottaall ppooppuullaattiioonn vvaacccciinnaatteedd aaggaaiinnsstt CCOOVVIIDD--1199

Note: Up to end of August 2021

Source: Our World in Data.

Note for authors: EU average is unweighted (the number of countries included in the average varies depending on the week). Data extracted on 06/09/2021.

54%

63%

62%

70%

0%10%20%30%40%50%60%70%80%90%100%

EU

Netherlands

Two doses (or equivalent) One dose

NL

EU

0% 50% 100%

Two doses (or equvlent) One dose

Accessibility - Unmet needs and use of teleconsultations during COVID-19

Option 1:

Netherlands

Option 2:

39%

42%

% using

teleconsultation

during first 12 months

of pandemic

21%

15%

Netherlands EU

% reporting forgone

medical care during

first 12 months of

pandemic

15

21

0

10

20

30

42

39

0

20

40

60

% reporting forgone medical

care during first 12 months

of pandemic

% using teleconsultation

during first 12 months of

pandemic

39%

42%

% using

teleconsultation

during first 12 months

of pandemic

21%

15%

Netherlands EU

% reporting forgone

medical care during

first 12 months of

pandemic

% reporting forgone

medical care during first

12 months of pandemic

% using teleconsultation

during first 12 months of

pandemic

% reporting forgone medical

care during first 12 months

of pandemic

% using teleconsultation

during first 12 months of

pandemic

NL EU27

4

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

2 Helth n the Netherlnds

Life expectancy temporarily dropped by

0.7 years in 2020 during the COVID-19

pandemic

In 2020, life expectancy at birth for the Dutch

population was 81.5 years, almost one year higher

than the average in the EU as a whole (80.6 years),

but lower than many of the top performing countries

(Figure 1). Men in the Netherlands live almost two

years longer than the EU average, while Dutch women

live almost five months less. This comparatively weak

performance for women reflects the legacy of high

smoking rates in previous generations (see Section 3)

and which has increased the number of women with

lung cancer.

Progress in life expectancy in the previous two

decades was significant, but between 2010 and 2019,

women only gained 0.7 years in life expectancy, while

men gained 1.7 years, a slowdown that is not unique

to the Netherlands. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic,

overall life expectancy fell temporarily from 82.2 years

in 2019 to 81.5 years in 2020, representing a decline of

nearly 8.5 months.

Figure 1. Dutch life expectancy is 1.3 years below the best performing EU country but higher than the EU

average

Not Th EU vrg s wghtd Dt for Irlnd rfr to 2019

Sourc Eurostt Dtbs

COVID-19 accounted for a large number of

deaths in the Netherlands in 2020

In 2019, the leading causes of death in the

Netherlands were lung cancer, stroke and ischaemic

heart disease (Figure 2). Mortality rates from lung

cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

(COPD) continue to be among the highest in the EU,

despite some reductions over the years. In contrast,

mortality rates from stroke and ischaemic heart

disease remain among the lowest in the EU (see

Section 5.1).

In 2020, COVID-19 accounted for about 11600 deaths

in the Netherlands – almost 7% of all deaths –

while an additional 6400 deaths were attributed to

COVID-19 by the end of August 2021. The majority of

deaths were among people aged 60 and over. Overall,

the mortality rate from COVID-19 up to the end of

August 2021 was about 35% lower in the Netherlands

than the average across EU countries (approximately

1035 per million population compared with about

1590 for the EU average). However, the broader

indicator of excess mortality suggests that the direct

and indirect death toll related to COVID-19 in 2020

may have been higher (Box 1).

LLiiffee eexxppeeccttaannccyy aatt bbiirrtthh,, 22000000,, 22001100 aanndd 22002200

Select a country:

GEO/TIME 2000 2010 2020

22000000 22001100 22002200

Norway 78.8 81.2 83.3 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Iceland 79.7 81.9 83.1 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Ireland 76.6 80.8 82.8 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Malta 78.5 81.5 82.6 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Italy 79.9 82.2 82.4 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Spain 79.3 82.4 82.4 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Sweden 79.8 81.6 82.4 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Cyprus 77.7 81.5 82.3 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

France 79.2 81.8 82.3 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Finland 77.8 80.2 82.2 0 #N/A #N/A #N/A

Netherlands

83.3

83.1

82.8

82.6

82.4

82.4

82.4

82.3

82.3

82.2

81.8

81.6

81.5

81.3

81.2

81.1

81.1

80.9

80.6

80.6

78.6

78.3

77.8

76.9

76.6

75.7

75.7

75.1

74.2

73.6

65

70

75

80

85

90

2000 2010

Years

2020

Netherlands

EU

81.0

81.6

82.2

81.5

2010 2015 2019 2020

Years

Life expectancy at birth

5

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

Figure 2. Lung cancer, stroke and ischaemic heart disease are the leading causes of death in the Netherlands

Not Th numbr nd shr of COVID-19 dths rfr to 2020, whl th numbr nd shr of othr cuss rfr to 2019 Th sz of th COVID-19 box s

proportonl to th sz of th othr mn cuss of dth n 2019

Sourcs Eurostt (for cuss of dth n 2019) ECDC (for COVID-19 dths n 2020, up to w 53)

Box 1. Some gaps between COVID-19 deaths and excess mortality in 2020 are evident in the Netherlands

In the Netherlnds, s n mn other countres, the

ctul number of deths from COVID-19 s lel

to be hher thn the number of reported deths,

especll becuse there s no oblton to report

COVID-19 s cuse of deth untl t ppers on

deth certfctes, whch re onl vlble severl

months lter The number of COVID-19 deths

reported lso does not te nto ccount the possble

ncrese n deths from other cuses tht m rse

durn or fter the pndemc These m be due,

for exmple, to reduced ccess to helth servces

for non-COVID-19 ptents or fewer people seen

tretment becuse of fer of ctchn the vrus

(ndrect deths) The ndctor of excess mortlt

(defned s the number of deths from ll cuses

over nd bove wht would hve been normll

expected, bsed on bselne dt from the prevous

fve ers) cn provde broder mesure of the

drect nd ndrect mpct of COVID-19 on mortlt

tht s not ffected b ssues relted to testn nd

cuse-of-deth restrton prctces

In the Netherlnds, between Mrch nd December

2020, trends for excess deths nd reported COVID-19

deths were enerll consstent, but wth some

ncreses n the p between the two n Aprl nd

from md-October 2020 (Fure 3) A hetwve n

Auust 2020 ws probbl the cuse of reltvel

steep rse n excess deths t tht tme, nd ws not

connected wth COVID-19 Overll, excess mortlt

ccounted for bout 20 000 deths between Mrch

nd December 2020

Figure 3. COVID-19 and excess deaths peaked in spring 2020 in the Netherlands

Not Th clculton of xcss dths s bsd on th vrg for th prvous fv rs (2015-2019)

Sourcs ECDC (for COVID-19 dths) OECD bsd on Eurostt dt (for xcss dths)

- 500

0

500

1 000

1 500

2 000

2 500

COVID-19 deaths Excess deaths

Weekly number of deaths

COVID-19

11 598 (68%)

Lun cncer

10 262 (68%)

Stroe

9368 (62%)

Ischemc hert dsese

8 370 (55%)

Colorectl cncer

4 857 (32%)

Pneumon

3 374 (22%)

Brest

cncer

3 089 (20%)

Pncretc

cncer

3 024 (20%)

Alzhemer’s

dsese

4 116 (27%)

Chronc obstructve pulmonr

dsese

6984 (46%)

6

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

Most Dutch people report good health, but

sizeable disparities exist across income groups

In 2019, about 75% of Dutch people reported that

they were in good health – a greater share than in the

EU as a whole (69%). However, as in other countries,

people on lower incomes are less likely to report

good health; only 60% of those in the lowest income

quintile reported good health compared to 87% of

those in the highest (Figure 4).

The burden of cancer in the Netherlands is

considerable

According to estimates from the Joint Research

Centre based on incidence trends from previous years,

around 110000 new cases of cancer were expected in

the Netherlands in 2020. However, fewer people were

newly diagnosed with cancer than in previous years,

probably as a result of the pause in cancer screening

programmes in spring 2020 during the pandemic.

Prostate cancer is the main cancer among men, while

breast cancer is the leading cancer among women.

Colorectal and lung cancers are the second and third

leading cause of cancer among both sexes (Figure 5).

Despite having a substantial disease burden, with over

45000 deaths from cancer in 2019, cancer survival

rates in the Netherlands are higher than the EU

average (see Section 5.1).

Figure 4. Inequalities in self-reported health by

income level are relatively large in the Netherlands

Not 1 Th shrs for th totl populton nd th populton on low

ncoms r roughl th sm

Sourc Eurostt Dtbs, bsd on EU-SILC (dt rfr to 2019)

Figure 5. An estimated 110000 people in the Netherlands were expected to be diagnosed with cancer in 2020

Not Non-mlnom sn cncr s xcludd Utrus cncr dos not nclud cncr of th crvx

Sourc ECIS – Europn Cncr Informton Sstm

Others

Kidney

Non-Hodgkin

lymphoma

Skin melanoma

Bladder Lung

Colorectal

Prostate

After new data, select all and change font to 7 pt.

Adjust right and left alignment on callouts.

Enter data in BOTH layers.

Others

Non-Hodgkin

lymphoma

Bladder

Uterus

Skin melanoma

Lung

Colorectal

Breast

26%

3%

4%

7%

9% 11%

16%

24%

26%

3%

3%

4%

8%

12%

14%

30%

Men

61 755 new cases

Age-standardised rate (all cancer)

NL 759 per 100 000 populton

EU 686 per 100 000 populton

Age-standardised rate (all cancer)

NL 577 per 100 000 populton

EU 484 per 100 000 populton

Women

52 846 new cases

FFoorr ttrraannssllaattoorrss OONNLLYY::

0 20 40 60 80 100

Ireland

Greece

Cyprus

Iceland

Sweden

Spain

Netherlands

Norway

Belgium

Malta

Italy

Luxembourg

Austria

Romania

Denmark

EU

Finland

Bulgaria

France

Slovenia

Germany

Slovakia

Czechia

Croatia

Poland

Hungary

Estonia

Portugal

Latvia

Lithuania

High incomeTotal populationLow income

% of adults who report being in good health

Hh ncome Totl populton Low ncome

1

1

% of dults who report ben n ood helth

7

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

3 Rs fctors

Behavioural risk factors account for more than

one third of all deaths

More than one third (35%) of all deaths in the

Netherlands can be attributed to behavioural

risk factors – below the EU average of 39%. These

behaviours include smoking, dietary risks, alcohol

consumption and low physical activity (Figure 6). One

in five deaths in 2019 could be attributed to tobacco

consumption (including direct and second-hand

smoking), which is higher than the EU average (21%

compared to 17%). The second major risk factor is

dietary risks (including low fruit and vegetable intake,

and high sugar and salt consumption), which were

responsible for an estimated 11% of deaths in 2019 –

well below the EU average (17%). About 5% of deaths

that year were associated with alcohol consumption,

which is close to the EU average (6%). Environmental

factors such as air pollution, in the form of fine

particulate matter (PM

2.5

) and ozone exposure alone

accounted for nearly 5000 deaths in the Netherlands

in 2019 (or 3% of all deaths, compared to 4% in the

EU).

Figure 6. Tobacco consumption is the leading behavioural risk factor contributing to mortality in the Netherlands

Not Th ovrll numbr of dths rltd to ths rs fctors s lowr thn th sum of ch on tn ndvdull, bcus th sm dth cn b

ttrbutd to mor thn on rs fctor Dtr rss nclud 14 componnts such s low frut nd vgtbl nt, nd hgh sugr-swtnd bvrg

consumpton Ar polluton rfrs to xposur to PM

25

nd ozon

Sourcs IHME (2020), Globl Hlth Dt Exchng (stmts rfr to 2019)

Smoking and drinking rates in both adults and

adolescents have decreased

Adult smoking rates have declined following the

introduction of smoke-free working environments and

other policy changes (see Section 5.1), and are below

the EU average. In 2018, about one in eight 15-year-

olds in the Netherlands reported smoking cigarettes

in the past month – a substantial decline from 2014,

when it was one in five.

Overall consumption of alcohol among adults has

declined by about 20% since 2000, and is now

lower than in most other EU countries. Repeated

drunkenness among 15-year-olds is also slightly less

widespread in the Netherlands than across the EU,

with 19% of 15-year-olds reporting having been drunk

more than once in their life in 2018, compared with a

22% EU average.

Overweight and obesity rates are rising

The overweight and obesity rate among Dutch

teenagers and adults is lower than in most EU

countries (Figure 7). More than one in eight adults

(14%) in the country were obese in 2019, up from 10%

in 2002. These trends are a cause for concern, given

that obesity carries a significant risk for diabetes,

cardiovascular diseases and several different cancers.

This highlights the need to increase efforts to change

dietary habits among both children and adults.

Adults in the Netherlands have among the lowest

fruit and vegetable consumption in the EU, with

around 6 out of 10 reporting that they do not eat

at least one portion per day. A higher proportion

of adolescents report eating at least one vegetable

each day compared with the EU average, but it is

the opposite for fruit consumption: only about one

quarter (27%) of 15-year-olds reported eating at least

one fruit per day in 2018 – a lower proportion than the

EU average (31%).

Dietary risks

NL: 11%

EU: 17%

Tobacco

NL: 21%

EU: 17%

Alcohol

NL: 5%

EU: 6%

Air pollution

NL: 3%

EU: 4%

Low physical activity –

NL: 1% EU: 2%

8

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

Fewer than one in five teenagers engage in

moderate physical activity every day

While most adults in the Netherlands report at least

150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week,

this is not the case among 15-year-olds. Only 18%

of Dutch teenagers reported engaging in moderate

physical activity on a daily basis in 2018, with a lower

rate among girls: only 14% of girls reported doing at

least moderate activity each day, compared to 21%

of boys. While this exceeds the EU averages of 10%

of girls and 18% of boys, low physical activity can

affect other health outcomes and increases the risk of

overweight and obesity.

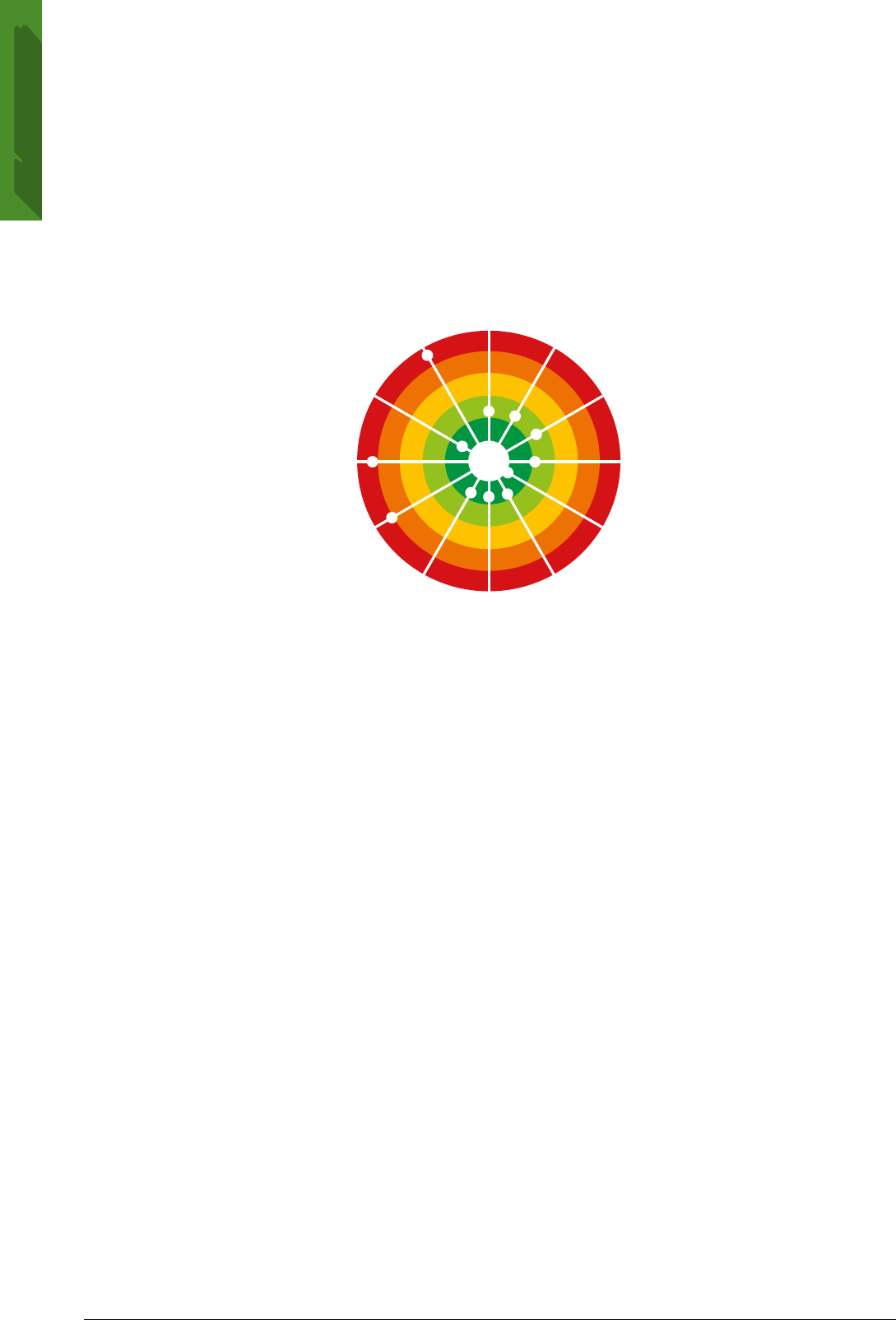

Figure 7. The Netherlands performs better than most other EU countries on many risk factors

Not Th closr th dot s to th cntr, th bttr th countr prforms comprd to othr EU countrs No countr s n th wht “trgt r” s thr s

room for progrss n ll countrs n ll rs

Sourcs OECD clcultons bsd on HBSC surv 2017-18 for dolscnts ndctors nd EHIS 2019 nd Dutch HIS for dults ndctors

4 The helth sstem

Three separate coverage schemes form the

basis of the Dutch health system

The Dutch government regulates and oversees three

schemes that together provide broad universal

health coverage. First, competing health insurers

administer a social health insurance (SHI) system

for curative care. The system, introduced in 2006,

mandates all residents to purchase insurance policies

that cover a defined benefits package set by the

government. Insurers must accept all applicants,

and they negotiate and contract with providers

based on quality and price. The SHI scheme covers

all specialist care, primary care, pharmaceuticals

and medical devices, adult mental health care, some

allied care services and community nursing. The

second scheme is a single-payer social insurance

system for long-term care, which is carried out by

the regionally dominant health insurer, and which

was the subject of a large reform in 2015 to rein in

the scope of the scheme and spending. The third is

a tax-funded social care scheme implemented by

the municipalities. The National Institute for Public

Health and the Environment (RIVM) provides guidance

for public health services at the national level, while

municipalities cover most services such as screening,

vaccination and health promotion (Box 2).

Spending on health as a share of GDP is slightly

above the EU average

In 2019, the Netherlands spent 10.2% of GDP in

health – slightly above the EU average of 9.9%.

This translates to EUR3967 per capita (adjusted

for differences in purchasing power), which is well

above the EU average of EUR3523. Expenditure

growth between 2013 and 2017 only increased by

1.0% on average per year, following the introduction

of a reform package that increased financial risk

6

Vegetable consumption (adults)

Vegetable consumption (adolescents)

Fruit consumption (adults)

Fruit consumption (adolescents)

Physical activity (adults)

Physical activity (adolescents)

Obesity (adults)

Overweight and obesity (adolescents)

Alcohol consumption (adults)

Drunkenness (adolescents)

Smoking (adults)

Smoking (adolescents)

Select dots + Effect > Transform scale 130%

OR Select dots + 3 pt white outline (rounded corners)

9

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

for insurers and providers and increased the

share of out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenditure.

In addition, the Dutch Ministry of Health signed

several agreements with stakeholders that aim

to keep spending growth within predefined levels.

However, between 2017 and 2019, annual health

expenditure growth rose to 2.3% per year. During the

COVID-19 pandemic, insurers and providers agreed

on measures to compensate revenue losses and extra

spending due to COVID-19. The government allocated

additional tax revenues for 2020 and 2021 to the

health sector, including for testing and contact tracing

(EUR476million in 2020 and EUR450million in 2021)

and intensive care unit (ICU) beds (EUR80.1million

and EUR93.9million).

A relatively large voluntary health insurance

sector contributes to low OOP payments

Following the abolition of the private insurance

scheme in 2006, public expenditure (government

spending and compulsory insurance) increased from

about two thirds (68.4%) of health spending in 2005 to

83.8% in 2006, before falling slightly to 82.6% in 2019.

This remains slightly above the EU average of 79.7%

(Figure 8).

OOP spending as a share of current health

expenditure was about two thirds of the EU-wide

average in 2019, at 10.6% in the Netherlands

compared to 15.4% in the EU. Around 57% of OOP

payments are due to cost-sharing, although general

practitioner (GP) care, maternal care and care from

district nurses remain free at the point of delivery. In

the Netherlands, health insurers may offer voluntary

health insurance (VHI) policies to cover services

outside the benefits package. This contributes to a

relatively large VHI sector (6.8% of health spending

compared to 4.9% in the EU in 2019), as individuals

who expect to incur high OOP payments usually take

out VHI (see Section 5.2).

Figure 8. Health spending per capita is above the EU average

Not Th EU vrg s wghtd

Sourc OECD Hlth Sttstcs 2021 (dt rfr to 2019, xcpt for Mlt 2018)

Box 2. The Netherlands took steps to implement a national-level response to the COVID-19 crisis

In ccordnce wth the ntonl pndemc response

pln n plce before the COVID-19 outbre, the

frst response focused on the reonl level n the

provnce of Noord-Brbnt, where the frst COVID-19

outbre occurred Soon, the response ws scled

up to the ntonl level under the mnement of

the RIVM (see Secton 53), whch coordntes the

reonll conducted testn, contct trcn nd

reportn of cses The RIVM lso hosts the Outbre

Mnement Tem, whch dvses the Prme

Mnster nd the Cbnet on necessr mesures, nd

conssts of medcl speclsts, vrolosts, medcl

mcrobolosts nd representtves of the ntonl

reference lbortor Throuhout the utumn of 2020,

the Netherlnds dd not pss n ntonl emerenc

leslton, nd muncpl uthortes could determne

whether to mplement emerenc decrees However,

the countr ntroduced the COVID-19 Temporr

Mesures Act on 1 December 2020, whch enbles

ntonl decson mn The Act cn be extended

nd stopped t n tme wth the reement of the

prlment

Sourc COVID-19 Hlth Sstms Rspons Montor

CCoouunnttrryy

GGoovveerrnnmmeenntt && ccoommppuullssoorryy iinnssuurraannccee sscchheemmeess VVoolluunnttaarryy iinnssuurraannccee && oouutt--ooff--ppoocckkeett ppaayymmeennttss TToottaall EExxpp.. SShhaarree ooff GGDDPP

Norway 4000 661 4661 10.5

Germany 3811 694 4505 11.7

Netherlands 3278 689 3967 10.2

Austria 2966 977 3943 10.4

Sweden 3257 580 3837 10.9

Denmark 3153 633 3786 10.0

Belgium 2898 875 3773 10.7

Luxembourg 3179 513 3742 5.4

France 3051 594 3645 11.1

EU27 22880099 771144 3521 9.9

Ireland 2620 893 3513 6.7

Finland 2454 699 3153 9.2

Iceland 2601 537 3138 8.5

Malta 1679 966 2646 8.8

Italy 1866 659 2525 8.7

Spain 1757 731 2488 9.1

Czechia 1932 430 2362 7.8

Portugal 1411 903 2314 9.5

Slovenia 1662 621 2283 8.5

Lithuania 1251 633 1885 7.0

Cyprus 1063 819 1881 7.0

2019

0.0

2.5

5.0

7.5

10.0

12.5

0

1 000

2 000

3 000

4 000

5 000

Government & compulsory insurance Voluntary insurance & out-of-pocket payments Share of GDP

% GDP

EUR PPP per capita

0.0

2.5

5.0

7.5

10.0

12.5

0

1 000

2 000

3 000

4 000

5 000

Government & compulsory insurance Voluntary insurance & out-of-pocket payments Share of GDP

% GDP

EUR PPP per capita

10

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

The Netherlands has the second highest share

of spending on long-term care in the EU

When measured in per capita terms, health spending

in the Netherlands is above the EU average for

outpatient care, long-term care and prevention,

and is below the average on inpatient care, retail

pharmaceuticals and medical devices (Figure 9). A

large long-term care sector, which covers elderly care,

care for disabled people and long-term mental care,

contributes to the relatively high overall spending

on health. Spending on retail pharmaceuticals and

medical devices is well below the EU average and

even decreased from 13.9% of total health spending

in 2010 to 11.2% in 2019. The Netherlands has among

the highest levels of spending on prevention, at

EUR131 per person, compared to an EU average of

EUR102, but this amount has not increased over time.

Between 2010 and 2019, the share of spending on

prevention dropped from 4.3% to 3.3% of total health

spending.

Figure 9. Long-term care expenditure exceeds that of most other EU countries

Not Th cost of hlth sstm dmnstrton s not ncludd 1 Includs hom cr nd ncllr srvcs (g ptnt trnsportton) 2 Includs onl th

hlth componnt 3 Includs curtv-rhblttv cr n hosptl nd othr sttngs 4 Includs onl th outptnt mrt 5 Includs onl spndng for

orgnsd prvnton progrmms Th EU vrg s wghtd

Sourcs OECD Hlth Sttstcs 2021, Eurostt Dtbs (dt rfr to 2019)

Nursing attracts more people to the profession

than in many other EU countries

In the last 10 years, the ratio of doctors to population

has increased from 3.4 to 3.7 per 1000 population,

close to the EU average of 3.9. The ratio of nurses

grew from 8.7 to 10.7 per 1000 population, which

is well above the EU average of 8.4. In 2019, 60%

more nurses graduated than in 2009, while doctors’

graduation rates rose by a more modest 26%. Nurses

in the Netherlands participate in task-shifting and

advanced nursing practices, creating a more attractive

work environment. Nurse specialists were granted

the authority to practise independently in 2012, and

this was codified in law in 2018. They are empowered

to prescribe all medicines within their competence

and to perform endoscopies, among other specified

services. However, the nursing workforce is

overburdened in hospitals, and nursing and home

care personnel also face shortages, which became

more pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic (see

Section 5.3). An above-average share of doctors work

as GPs – 24% of all physicians compared with 21%

across the EU.

Strong primary care and gatekeeping contribute

to low hospital admission rates

Health services are overwhelmingly provided by

private non-profit providers, and most physicians

are self-employed. The Netherlands operates a strict

gatekeeper system. Patients require a referral from a

GP to visit hospital and specialist care, including for

COVID-19 (see Section 5.3). Although the Netherlands

reports comparatively high numbers of outpatient

contacts, it also has relatively low rates of hospital

discharges, suggesting that strong primary care and

outpatient specialist treatment manage to keep

people out of hospitals (Figure 10). Both long-term

care and mental health care reforms were designed

for delivery in outpatient settings to respond to

historically high institutionalisation rates (Kroneman

et al., 2016).

1 022

617

1 010

630

102

0

0

0

0

0

1 128

1 112

961

445

131

Netherlnds

Preventon Phrmceutcls

nd medcl devces

Inptent cre Lon-term cre Outptent cre

0

200

400

600

800

1 000

1 200

1 400

EU27EUR PPP per cpt

29%

of totl

spendn

28%

of totl

spendn

24%

of totl

spendn

11%

of totl

spendn

3%

of totl

spendn

11

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

Figure 10. The Netherlands has the lowest inpatient use in the EU

Not Th EU vrg s unwghtd

Sourc OECD Hlth Sttstcs nd Eurostt Dtbs (dt rfr to 2019 or nrst r)

5 Performnce of the helth sstem

51 Effectiveness

Low mortality from preventable and treatable

causes point to effective health interventions

Mortality from preventable causes in the Netherlands

compares favourably with the rate across the EU as

a whole, at 129 deaths compared to 160 per 100000

population (Figure 11), reflecting both a lower

prevalence of risk factors and a lower incidence

of many of these health issues compared to most

other EU countries. Lung cancer accounts for 30% of

preventable deaths in the Netherlands, making it the

largest contributor to preventable mortality. Since the

early 2000s, the government has implemented several

public health policies aiming to minimise the impact

of behavioural risk factors and social determinants of

health. Smoking was banned in workplaces in 2004,

and in cafés and restaurants in 2008, while alcohol

control measures implemented in 2013 focused on

reducing alcohol use among teenagers. The National

Prevention Agreement concluded in 2018 prompts

municipalities to implement regional and local

agreements to improve health outcomes and reduce

health inequalities in their populations. So far,

14 initiatives with an average of 41 participating

organisations have been developed, working

towards the 2040 targets to have a smoke-free

generation, reduce the share of the overweight and

obese population from 50% to 38% and decrease

problematic alcohol abuse.

The Netherlands reports one of the lowest mortality

rates from treatable causes – that is, deaths that

could have been avoided through effective health

care interventions (Figure 11). These rates remain low

compared to the rest of the EU in spite of the above-

average mortality from colorectal and breast cancer

in the Netherlands, which accounted for more than

40% of treatable deaths in 2018. Mortality rates from

other treatable causes – such as ischaemic heart

disease, stroke and pneumonia – were among the

lowest in the EU.

50 200 250 350300150100

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Number of doctor consultations per individual

Discharges per 1 000 population

EU average: 6.7

EU average: 172

High inpatient use

Low outpatient use

High inpatient use

High outpatient use

Low inpatient use

Low outpatient use

Low inpatient use

High outpatient use

NO

DK

CZ

MT

LT

LU

IE

FR

SI

RO

PL

SK

IT

ES

CY

BG

SE

DE

EL

IS

AT

PT

FI

BE

HR

EU

NL

EE

HU

LV

12

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

Figure 11. Deaths from preventable and treatable causes are lower than in most EU countries

Not Prvntbl mortlt s dfnd s dth tht cn b mnl vodd through publc hlth nd prmr prvnton ntrvntons Trtbl mortlt

s dfnd s dth tht cn b mnl vodd through hlth cr ntrvntons, ncludng scrnng nd trtmnt Hlf of ll dths for som dsss

(g schmc hrt dss nd crbrovsculr dss) r ttrbutd to prvntbl mortlt th othr hlf r ttrbutd to trtbl cuss Both

ndctors rfr to prmtur mortlt (undr g 75) Th dt r bsd on th rvsd OECD/Eurostt lsts

Sourc Eurostt Dtbs (dt rfr to 2018, xcpt for Frnc 2016)

The Netherlands faces increasing numbers of

avoidable admissions for chronic conditions

While the Netherlands reports an overall low number

of avoidable hospitalisations, avoidable admissions

for asthma and COPD have increased between 2007

and 2019 from 182 to 208 avoidable admissions per

100000 population. The Netherlands has responded

to this with information campaigns and several

policy actions over the past decade. Initial results

bode well for the effect of these policies, as avoidable

admissions for COPD dropped from 213 to 200

avoidable hospitalisations per 100000 population

between 2015 and 2016. Additional measures

implemented in 2020 introduced neutral packaging

for cigarettes, a ban on flavoured e-cigarettes, a

prohibition of smoking in schoolyards, a ban on

displays of tobacco products in supermarkets and

raised excise duties on tobacco products. In addition,

strong primary care and outpatient care contribute

to minimising hospital admission rates for diabetes

and congestive heart failure, which are about half

the EU average. Bundled payments, whereby a single

payment covers all costs of services supplied by

multiple providers for a defined episode of care, also

play a role in coordinating care for diabetes, COPD

and cardiovascular disease patients.

Although above the EU average, influenza

vaccination rates were on a downward trend

before the pandemic

In 2019, the Netherlands vaccinated 61% of its

population over the age of 65 for seasonal influenza

– well above the EU average of 42%, although still

below the target of 75% recommended by the

104

104

111

113

115

118

120

129

130

132

134

138

139

146

152

156

157

159

160

175

195

222

226

239

241

253

293

306

326

326

59

63

64

65

65

65

66

68

71

71

73

75

76

77

79

83

85

90

92

92

124

133

133

133

165

176

186

188

196

210

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350

0 50 100 150 200 250

104

104

111

113

115

118

120

129

130

132

134

138

139

146

152

156

157

159

160

175

195

222

226

239

241

253

293

306

326

326

59

63

64

65

65

65

66

68

71

71

73

75

76

77

79

83

85

90

92

92

124

133

133

133

165

176

186

188

196

210

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350

0 50 100 150 200 250

104

104

111

113

115

118

120

129

130

132

134

138

139

146

152

156

157

159

160

175

195

222

226

239

241

253

293

306

326

326

59

63

64

65

65

65

66

68

71

71

73

75

76

77

79

83

85

90

92

92

124

133

133

133

165

176

186

188

196

210

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350

0 50 100 150 200 250

13

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

WHO. However, influenza vaccination rates in the

Netherlands among those aged 65 and over have

decreased by nearly 20 percentage points in the last

10 years. Influenza vaccinations are free for people

over the age of 60, yet vaccination campaigns are

obstructed by uncertainty about the effectiveness and

side effects of the vaccine, as well as the perceived

low risk of contracting or dying from influenza. This

perception may have changed during the COVID-19

pandemic, however, as demand for the flu vaccine

grew. Some GP practices temporarily asked individuals

between 60 and 70 years old with no underlying

conditions to refrain from getting a flu vaccination to

prioritise doses for those over 70 years old.

Dutch cancer survival rates are high but

screening rates for breast and cervical cancer

are decreasing

The Netherlands offers population screening

programmes for cervical cancer, breast cancer and

colorectal cancer. Cervical cancer screening has a

participation rate similar to the EU average, with

56% of women aged 20-69 screened within the past

two years, although participation has declined over

recent years from 68% in 2007. Similarly, breast

cancer screening rates are higher than the EU

average (76% compared to 59%), but participation

has also decreased over the last decade (Figure 12).

The relatively new Colorectal Cancer Screening

Programme (2014) covers all individuals between

55 and 75 years of age. A programme evaluation

in 2019 found that participation rates (73%) were

above expectations, with 3.9million people sending

in self-screening tests between 2014 and 2017,

contributing to higher than anticipated detection of

new colorectal cancer cases. Based on these results, it

is predicted that by 2030 nearly one in five colorectal

cancer cases and over one in three colorectal cancer

deaths may be prevented (RIVM, 2019).

Figure 12. Breast cancer screening rates are high, but have declined over the last 10 years

Not Th EU vrg s unwghtd For most countrs, th dt r bsd on scrnng progrmms, not survs

Sourcs OECD Hlth Sttstcs 2021 nd Eurostt Dtbs

Five-year cancer survival rates have improved over the

last decade and are generally above the EU average

(Figure 13). Although the Netherlands does not have

a national cancer plan, health care professionals,

researchers, policy makers and patient organisations

have come together in the Cancer Survivorship Care

Taskforce to advocate a national action plan that

recognises the continuing needs of cancer patients

and survivors. This aligns with one of the key action

areas of the recent Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan

to improve quality of life of cancer patients and

survivors, including rehabilitation and measures to

support social integration and re-integration in the

workplace (European Commission, 2021a).

Selected country

95

83

81

80

77

76

75

74

72

72

69

66

61

61

61

60

60

59

56

54

53

53

50

49

39

39

36

31

31

9

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

-

14

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

Figure 13. Five-year survival rates across six cancers exceed the EU23 average

Not Dt rfr to popl dgnosd btwn 2010 nd 2014 Chldhood lum rfrs to cut lmphoblstc cncr

Sourc CONCORD Progrmm, London School of Hgn & Tropcl Mdcn

1. The data from the Eurofound survey are not comparable to those from the EU-SILC survey because of differences in methodologies.

Promising initiatives have arisen to improve the

quality of health care

In the Dutch health care system, competing insurers

are expected to play a key role in improving quality

through contract negotiations with health care

providers (see Section 4). In practice, insurers

emphasise volume and price more than quality

in their contracting decisions, partly due to the

fragmentation and administrative burden of

collecting quality indicators. The Dutch Health Care

Institute has been tasked with developing reliable

and meaningful quality indicators and drawing

up a multi-year care improvement agenda, in

consultation with all parties involved in health care.

These initiatives can then be used to improve care,

enhance shared decision making and ultimately guide

contracting with providers.

Furthermore, some insurers have started creating

bottom-up longer-term contracts with providers

centred on value-based care, where providers and

professionals can define key performance indicators

for quality of care and delivery innovations. Medical

professional groups and the government also

contribute to quality improvement activities, such

as a new long-term care quality framework aims to

improve the quality of care in nursing homes. An

initiative to provide “the right care at the right place”

(de juiste zorg op de juiste plek) also has gained

momentum, and has helped physicians and patients

to determine the appropriate setting for COVID-19

treatment (see Section 5.3).

52 Accessibility

Very few Dutch people reported unmet needs

for medical treatment until the COVID-19

pandemic

In the Netherlands, government regulation guarantees

universal and equal access to affordable care. As a

result, the Dutch tend to report very low levels of

unmet needs for medical care (Figure 14). However,

this changed during the COVID-19 pandemic:

according to the Eurofound (2021) survey

1

, 15% of

respondents reported that they needed a medical

examination or treatment that they had not received

during the first 12 months of the pandemic. The

average reported for the EU as a whole was 21%.

The Netherlands did not shut down providers

at a national level, yet at various points during

the pandemic some hospitals postponed

non-urgent treatments due to regional outbreaks.

The professional organisations of dentists and

paramedical care providers decided to postpone all

non-emergency treatments from mid-March until

early May 2020. Cancer screening appointments were

also postponed from the onset of the pandemic until

mid-May (colon cancer), mid-June (breast cancer) and

July 2020 (cervical cancer). To resume care, multiple

stakeholder groups worked together to create a list

of diagnoses with an urgency indication, aiming to

address the most urgent plannable care first. The

Netherlands also encouraged teleconsultations as

much as possible, with about 40% of the population

taking part in a remote consultation (Eurofound,

2021).

Prostate cancer Childhood leukaemia Breast cancer Cervical cancer Colon cancer Lung cancer

Netherlands: 89 % Netherlands: 90 % Netherlands: 87 % Netherlands: 68 % Netherlands: 63 % Netherlands: 17 %

EU23: 87 % EU23: 85 % EU23: 82 % EU23: 63 % EU23: 60 % EU23: 15 %

15

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

Figure 14. The Dutch population had among the

lowest levels of unmet needs in the EU in 2019

Not Dt rfr to unmt nds for mdcl xmnton or trtmnt

du to costs, dstnc to trvl or wtng tms Cuton s rqurd n

comprng th dt cross countrs s thr r som vrtons n th

surv nstrumnt usd

Sourc Eurostt Dtbs, bsd on EU-SILC (dt rfr to 2019, xcpt

Iclnd 2018)

The health system provides broad coverage,

with voluntary health insurance covering some

gaps

Around 99.9% of the Dutch population has health

insurance, which covers a wide range of services.

Among other things, the benefits package includes

primary care, outpatient specialist care, hospital care,

maternal services, in vitro fertilisation (maximum

of three cycles), physiotherapy for chronic illness,

mental health treatment and ambulance transport.

Public spending accounts for 91% of inpatient care,

85% of outpatient care and 67% of outpatient

pharmaceuticals – all above the EU averages

(Figure 15).

The Netherlands covered the costs of COVID-19

testing, but individuals needed a physician referral

for a test until June 2020 (see Section 5.3). In an

unprecedented yet far-sighted measure, the Dutch

Healthcare Institute, which advises the Minister

of Health on the services to include in the basic

benefits package, determined that rehabilitation

care for COVID-19 patients should be included

if recommended by a physician. Specifically,

a maximum of 50 physical therapy sessions, 8

occupational therapist treatments and 7 dietician

sessions are reimbursable for up to six months after

COVID-19 infection.

Dental care for adults and some paramedical care

are not covered by the benefits package. Many

Dutch people purchase VHI to cover these services

– particularly dental care. Despite not being covered

in the benefits package, a very low proportion of the

population (0.4%) report unmet needs for dental care,

which is substantially below the EU average of 2.8%.

Figure 15. The public share of financing is higher than the EU average across all areas of health care, with the

exception of dental care

Not Outptnt mdcl srvcs mnl rfr to srvcs provdd b gnrlsts nd spclsts n th outptnt sctor Phrmcutcls nclud prscrbd

nd ovr-th-countr mdcns s wll s mdcl non-durbls Thrputc pplncs rfr to vson products, hrng ds, whlchrs nd othr

mdcl dvcs

Sourc OECD Hlth Sttstcs 2021 (dt rfr to 2019 or nrst r)

CCoouunnttrryy LLooww iinnccoommee TToottaall ppooppuullaattiioonn HHiigghh iinnccoommee LLooww iinnccoommee TToottaall ppooppuullaattiioonn HHiigghh iinnccoommee

Selected country

0 5 10 15 20

Estonia

Greece

Romania

Finland

Latvia

Poland

Iceland

Slovenia

Slovakia

Ireland

Belgium

Denmark

Italy

Portugal

EU 27

Bulgaria

Croatia

Lithuania

Sweden

France

Cyprus

Hungary

Norway

Czechia

Austria

Germany

Luxembourg

Netherlands

Spain

Malta

Low incomeTotal populationHigh income

% reporting unmet medical needs

Hh ncome Totl populton Low ncome

Unmet needs for medical care

NNeetthheerrllaannddss

89%

91%

0% 50% 100%

EU

Netherlands

Inpatient care

75%

85%

0% 50% 100%

Outpatient medical

31%

12%

0% 50% 100%

Dental care

57%

67%

0% 50% 100%

Pharmaceuticals

37%

45%

0% 50% 100%

Therapeutic

Inpatient care

Outpatient

medical care Dental care Pharmaceuticals

Therapeutic

appliances

Publc spendn s proporton of totl helth spendn b tpe of servce

16

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

Health care costs are partly paid through an

out-of-pocket mandatory deductible

OOP spending fell from a peak of 11.6% of total

health spending in 2014 to 10.6% in 2019, and stands

well below the EU average of 15.4% (Figure 16). A

large share of OOP spending in the Netherlands

comes from the mandatory deductible, which requires

patients to pay a minimum amount before the insurer

begins to cover services. The mandatory deductible

increased from EUR150 in 2008 to EUR385 in 2016.

The intention was that it should grow in line with

other items in the health budget, but in 2017 the

government coalition decided to keep the deductible

at its current level, while some opposition parties

wanted to abolish it entirely. The deductible does not

apply to GP care, maternity care, district nursing and

care for children under the age of 18, which are all

available without cost-sharing.

The main categories of OOP spending include

pharmaceuticals, inpatient and long-term care

contributions under the Long-term Care Act. Since

2019, the Netherlands has capped OOP spending on

pharmaceuticals at EUR250 per year. For residential

long-term care, the country applies income-

dependent cost-sharing, ranging from no cost-sharing

to EUR2419 per month, although not all OOP

payments are related to care delivery and may include

housing costs. Furthermore, the Social Support Act

offers the opportunity for municipalities to provide

financial compensation for health care costs incurred

by patients with chronic conditions on low incomes,

and some municipalities negotiate insurance policies

with generous benefits targeted at low-income groups.

Figure 16. Inpatient care and pharmaceuticals account for over 40% of out-of-pocket payments

Not Th EU vrg s wghtd VHI lso ncluds othr voluntr prpmnt schms

Sourc OECD Hlth Sttstcs 2021 Eurostt Dtbs (dt rfr to 2019)

The Netherlands has easily accessible health

care services

The Netherlands has a dense network of health care

providers, ensuring high geographical availability of

services. In 2020, fewer than 0.15% of the population

had to travel more than 10 minutes by car to the

nearest GP practice, and GP out-of-hours centres

cover care outside office hours. However, GP practices

struggle to replace GPs after retirement, and shortages

are becoming a concern.

Although there have been a substantial number

of mergers between hospitals over the last decade,

this has not yet affected the number of locations for

accessing health care. In the Netherlands, 99% of the

population lived within 30 minutes from a hospital by

car in 2020 (Volksgezondheidenzorg, 2021). However,

the Dutch system has been experiencing excessive

waiting times in some outpatient departments.

Mental health care for children is of particular

concern, as waiting times can exceed one year. It

remains unclear how the pandemic will affect waiting

times in the longer term.

Typically, insurance companies have the option of

reimbursing only 75% of costs of services provided

by non-contracted providers. This could result in

financial barriers to accessing some hospitals for

patients who purchase cheaper (“budget”) insurance

policies that contract a limited number of providers.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, insurers agreed

to cover care delivered by all hospitals in 2020 and

2021, even if they are outside their networks (see

Section 5.3).

Government/compulsory schemes 82.6%

VHI 6.8%

Inpatient 2.1%

Outpatient medical

care 1.7%

Pharmaceuticals 2.3%

Dental care 0.7%

Long-term care 1.8%

Others 2%

Government/compulsory schemes 79.7%

VHI 4.9%

Inpatient 1.0%

Outpatient medical

care 3.4%

Pharmaceuticals 3.7%

Dental care 1.4%

Long-term care 3.7%

Others 2.2%

Netherlands

Overall share of

health spending

Distribution of OOP

spending by function

OOP

10.6%

EU

Overall share of

health spending

Distribution of OOP

spending by function

OOP

15.4%

17

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

Concerted policy efforts to reduce

pharmaceutical expenditure have paid off

The Netherlands spends less on outpatient

pharmaceuticals than most other EU countries (see

Section 4). Several factors – including a long history

of volume and price control policies, a conservative

approach by GPs to issuing prescriptions and

well-established health technology assessment (HTA)

processes – have contributed to this result. Further,

the share of generic medicines by volume in the

pharmaceuticals market is the second highest after

Germany among EU countries for which data are

available. These efforts to control prices and promote

generics contribute to more affordable medicines for

patients.

A promising development is the BeNeLuxA

initiative, which aims to improve collaboration on

pharmaceutical policy and procurement; it includes

co-operation between Belgium, the Netherlands,

Luxembourg, Austria and Ireland in the fields of

horizon scanning, information sharing and policy

exchange, HTA, and pricing and reimbursement.

The BeNeLuxA initiative’s goals are consistent

with the European Commission’s pharmaceutical

strategy for Europe, adopted in November 2020,

which aims to ensure that patients have access to

innovative and affordable medicines while supporting

the competitiveness, innovative capacity and

sustainability of the EU’s pharmaceutical industry

(European Commission, 2020).

53 Resilience

This section on resilience focuses mainly on the

impacts of and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic

2

.

As noted in Section 2, the pandemic had a major

impact on population health and mortality in the

Netherlands, with around 18000 COVID-19 deaths

recorded between January 2020 and the end of August

2021. Measures taken to contain the pandemic

also had an impact on the economy, and Dutch

GDP is estimated to have declined by 3.8% in 2020,

compared to an EU average fall of 6.2%.

The Netherlands’ response to COVID-19

included measures at both regional and

national levels

The first case of COVID-19 was identified on

27February 2020 in the province of Noord-Brabant.

By 6March, residents of the province were advised

to stay at home and limit social contacts. This was

scaled up to the entire country by 12March as the

number of cases rose; the Netherlands quickly

implemented a 1.5-metre physical distancing

2. In this context, health system resilience has been defined as the ability to prepare for, manage (absorb, adapt and transform) and learn from shocks (EU Expert

Group on Health Systems Performance Assessment, 2020).

requirement and closed schools, restaurants

and non-essential in-person work, as well as

implementing other restrictive measures in the

following days (Figure 17). The measures to prevent

transmission remained in place through April 2020,

and primary schools were the first to reopen on

11May.

Further relaxation of measures continued through

summer 2020, but high infection rates in large cities

prompted some regional measures in August. As

September and October brought progressively higher

case numbers, restrictive measures heightened,

limiting the number of people who could gather

in a group and shutting down public venues. On

15December 2020, the Netherlands imposed the

strictest national restrictions to date, followed by a

curfew lasting from 23January 2021 until 28April

2021. Again, primary schools reopened first, on

8February 2021. The Netherlands progressed through

its four phases of reopening between 28April 2021

and 26June 2021. Shortly after the final reopening

phase, the Netherlands saw an exponential rise in

cases, mostly among young adults. This dropped

sharply in late summer after a reimposition of

measures restricting nightlife and large events.

The Netherlands had pandemic preparedness

tools in place prior to COVID-19

The Netherlands has a comprehensive pandemic

response plan, which was a key plank in the country’s

preparedness toolkit. Coordinated by the RIVM, it

describes in detail the general actions to take in the

case of an infectious disease crisis, including which

measures should be taken in which phase of the

crisis, and who is responsible for determining the

crisis phase.

A fragmented laboratory landscape initially

limited the number of tests performed

Prior to June 2020, testing for COVID-19 required

individuals to obtain a physician referral. After

1June, those with symptoms could register for testing

using a dedicated phone number without a referral,

but bottlenecks in testing capacity caused some

accessibility gaps. Generally, testing is performed

at the central test locations of the public health

services, under the coordination of the RIVM. At

the end of 2020, “XL” testing facilities were opened

at the national airport and in large cities; these

operated as public–private partnerships. Self-tests

started to become available at the end of March 2021

in some pharmacies, with further expansion to all

supermarkets and pharmacies in April 2021.

18

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

In September 2020, the Netherlands Court of Audit

published an evaluation of the country’s testing policy

(Algemene Rekenkamer, 2020). The report revealed

that the government did not have a clear view of

the capacity of the Dutch testing laboratories and

the supplies necessary for testing. The Netherlands

has a fragmented landscape of labs that use a

multitude of testing systems, which have experienced

varying problems with acquiring sufficient supplies.

As a result, the number of tests performed has

lagged behind the available capacity. For example,

in September 2020 the total testing capacity was

28000 per day, but the number of tests conducted on

average every day was 10000 below this capacity. This

contributed to the Netherlands having lower weekly

testing rates for much of 2020, but by September it

had surpassed the EU average (Figure 18).

Figure 18. Testing activity in the Netherlands caught up to the EU average in September 2020

Not Th EU vrg s wghtd (th numbr of countrs ncludd n th vrg vrs dpndng on th w)

Sourc ECDC

Figure 17. The number of COVID-19 cases reported in the second wave far exceeded that in the first wave

Not Th EU vrg s unwghtd (th numbr of countrs usd for th vrg vrs dpndng on th w)

Sourcs ECDC for COVID-19 css nd uthors for contnmnt msurs

Weekly cases per 100 000 population

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

500

Netherlands European Union

12 Mrch 2020

Dutch ctzens dvsed to

st home nd lmt socl

contcts

October 2020

Restrctons

re-ntroduced

23 Jnur 2021

Curfew

mplemented

26 June 2021

Fourth step of the

reopenn pln ll

estblshments open

28 Aprl 2021

Frst step of the reopenn

pln curfew lfted

1 June 2020

Resturnts nd

brs reopen

TTeessttiinngg aaccttiivviittyy

Note: The EU average is weighted (the number of countries included in the average varies depending on the week).

Source: ECDC.

Data extracted from ECDC on 15/03/2021 at 12:41 hrs.

CCoouunnttrryy 1100//0022//22002200 1177//0022//22002200 2244//0022//22002200 0022//0033//22002200 0099//0033//22002200 1166//0033//22002200 2233//0033//22002200 3300//0033//22002200 0066//0044//22002200

Austria #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A 139

Belgium #N/A #N/A 1 38 86 148 236 333 464

Bulgaria #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A #N/A

Croatia 0 0 4 3 13 48 103 158 218

Cyprus #N/A #N/A #N/A 7 2 26 43 40 43

Czechia 0 0 1 7 40 116 248 399 422

Denmark 0 0 6 14 85 126 172 485 478

Estonia 0 0 4 18 91 201 557 840 726

CCoouunnttrryy

Austria

Belgium

Bulgaria

Cyprus

Czechia

Denmark

European Union

Finland

France

Greece

Hungary

Iceland

Italy

Latvia

Lithuania

Malta

Netherlands

Norway

Portugal

Romania

Slovakia

Spain

Sweden

0

500

1 000

1 500

2 000

2 500

Belgium European Union Germany Netherlands

Weekly tests per 100 000 population

WWeeeekk

30-Dec-19

6-Jan-20

13-Jan-20

20-Jan-20

27-Jan-20

3-Feb-20

10-Feb-20

17-Feb-20

24-Feb-20

2-Mar-20

9-Mar-20

30-Mar-20

6-Apr-20

13-Apr-20

20-Apr-20

27-Apr-20

4-May-20

11-May-20

18-May-20

25-May-20

1-Jun-20

8-Jun-20

29-Jun-20

6-Jul-20

13-Jul-20

20-Jul-20

27-Jul-20

3-Aug-20

10-Aug-20

17-Aug-20

24-Aug-20

31-Aug-20

7-Sep-20

28-Sep-20

5-Oct-20

12-Oct-20

19-Oct-20

26-Oct-20

2-Nov-20

9-Nov-20

16-Nov-20

23-Nov-20

30-Nov-20

7-Dec-20

28-Dec-20

4-Jan-21

11-Jan-21

18-Jan-21

25-Jan-21

1-Feb-21

8-Feb-21

15-Feb-21

22-Feb-21

19

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

Some public health services had to limit contact

tracing activities due to capacity constraints

In addition to running testing locations, the 25

regional public health services oversee contact

tracing activities. The services temporarily reassigned

nearly all health care-related personnel to perform

contact tracing and staff helplines. Contact tracing

started when the Netherlands recorded its first case

in February 2020. When case numbers peaked in the

middle of September 2020, 10 of the public health

services announced that they had to limit contact

tracing: at this time, they only had the capacity to call

individuals living in the same household or those at

high risk. In addition, informed contacts were asked

to report to the public health service only if they had

symptoms.

The Dutch contact tracing app experienced

delays in launching due to regulatory hurdles

The Dutch government developed the “Coronamelder”

(Corona detector) application to support tracing of

contacts of people confirmed to have COVID-19.

Downloading and using the app is voluntary, and

infections can be reported anonymously. At first, the

Netherlands issued a tender and evaluated seven

apps, but after an initial assessment none of these

appeared to meet the necessary privacy criteria.

Therefore, the Dutch government started developing

its own open source app with a group of in-house

experts. It was piloted in a few regions in August

2020 in a testing phase, and the national launch was

originally planned for 1September. After delays in

legislative approval, the app was launched nationally

on 10October 2020, and it became inter-operable with

apps from other European countries at the end of

November 2020.

Debates on the value of wearing face masks

continued until autumn 2020

Initially, the RIVM stated that face masks have a

limited effect on preventing transmission and could

lead to a misperception of safety, compromising

physical distancing rules. The government supported

this view, but made face masks compulsory on

public transportation from 1June 2020, as physical

distancing was not feasible. The government also

granted local mayors discretion on requiring face

masks, following petitions by several mayors,

who pointed out that physical distancing was not

feasible owing to the concentration of people. As

evidence on the efficacy of face masks increased, on

14October 2020, the Netherlands made mask-wearing

compulsory for everyone aged 13 and older inside

public buildings, with some exemptions. The

conflicting guidance about whether to wear a face

mask contributed to fewer than 20% of Dutch people

wearing a mask outside the home between April and

September 2020, but mask-wearing rose sharply by

the end of 2020 (Figure 19).

Figure 19. The mask-wearing rate shot up after it

became obligatory in October 2020

Sourc YouGov dt (http//wwwcovddthubcom/)

The Netherlands rapidly scaled up its intensive

care unit bed capacity to accommodate

COVID-19 patients

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Netherlands had

1150 available ICU beds occupied at a 70% rate on

average. The number of ICU beds in the Netherlands,

at 6.7 beds per 100000 population, falls below many

other countries in Europe, including neighbouring

Germany (33.4) and Belgium (17.4). At the beginning

of April 2020, the number of patients with COVID-19

treated in ICUs exceeded pre-existing capacity

(Figure 20). In response, the country quickly made a

plan to increase its ICU bed capacity progressively

in March and April, surpassing 1700 beds to treat

COVID-19 patients in the second week of April. In

June 2020, the number of COVID-19 patients in

ICUs dropped below 100 and remained low over

the summer. The National Coordination Centre for

Distribution of Patients took on a steering role in

the allocation of COVID-19 patients among Dutch

hospitals.

0

20

40

60

80

100

Netherlands Sweden France Italy

% of people reporting to always wear a mask outside their home

20

Stte of Helth n the EU The Netherlnds Countr Helth Profle 2021

Figure 20. Intensive care unit occupancy rates exceeded pre-existing capacity only for a short period

Not Th blu ln rprsnts th dl numbr of COVID-19 ptnts n ICU unts th orng ln rprsnts th ntl bd cpct n ICU unts bfor th

pndmc th orng dshd ln rprsnts th ddtonl bd cpct moblsd durng th pndmc

Sourcs OECD/Europn Unon (2020) Llor (2020)

Patients were transferred within and outside

the Netherlands for treatment

To ensure optimal use of ICU beds, COVID-19 patients

and other patients who potentially required ICU care

were sometimes transferred to other hospitals. For

instance, at one point during the first wave, 32 of the

34 COVID-19 patients in the Groningen hospitals in

the north of the Netherlands were from the southern

provinces of Noord-Brabant and Limburg. These

transfers involved up to 100 patients per day at the

end of March 2020, but tapered off by the end of

April. The army coordinated the operation using

ambulances, mobile ICUs, a special ICU bus and

two helicopters, with assistance from police escorts

to ensure smooth transfers. The Netherlands also

transferred patients to Germany, and included the use

of ICU beds in Germany in its preparation plans for

the second wave.

General practitioners coordinated COVID-19

care while implementing measures to maintain

routine services

Outside of hospitals, GPs are the first contact point

for potential COVID-19 cases. GPs determine whether

the patient should be admitted to hospital, and

until June 2020 decided whether the patient should

receive testing. If possible beforehand, the physician

discusses the consequences of an ICU admission in

a shared decision-making process with the patient,

which is standard practice in the Netherlands. Based

on this discussion, patients are able to decide for

themselves whether to receive treatment in an ICU or

at home.

To maintain routine care, GPs were advised to

organise separate office hours for patients with

respiratory complaints, to abolish walk-in office hours

and to use video instead of face-to-face consultations

whenever possible. Despite these care adaptations,

the volume of services provided decreased

significantly, particularly in the first wave. Between

12March and 20April, GPs issued approximately

360000 fewer referrals than usual, and about 290500

previously issued referrals did not lead to a specialist

consultation.

The COVID-19 vaccination rollout encountered

some initial obstacles but accelerated quickly

The initial vaccination plan created by the Dutch

Health Council prioritised individuals over the age

of 60 and at-risk groups as the first to receive a

COVID-19 vaccination. This prioritisation largely

reflected the risk of COVID-19 mortality for these

groups, particularly those living in long-term care

facilities. However, hospital organisations emphasised

that health workers in COVID-19 wards and ICU

units should receive the first vaccinations, followed

by nursing home personnel and GPs. This conflicting

advice, combined with delays in procuring the

vaccine, led to a slower start to vaccinations than

in many other EU countries. After a slow start, the

vaccination rate increased and surpassed the EU

average in May 2021. This contributed to a reduction

in the number of deaths due to COVID-19 in the

Netherlands (Figure 21).

The RIVM oversees the vaccination campaign, and