31

limited to refueling. After 2000, and especially after 2006,

law enforcement increased the risks of shipping directly to

Mexico. Consequently, Central America took on new

importance as a transit and storage area, and parts of the

Caribbean were reactivated.

This can be seen in the seizure figures. In the mid-1980s,

over 75% of the cocaine seized between South America and

the United States was taken in the Caribbean, and very

little was seized in Central America. By 2010, the opposite

was true: over 80% was seized in Central America, with less

than 10% being taken in the Caribbean. The bulk of the

cocaine seized in recent years in the Caribbean has been

taken by the Dominican Republic, which is also a transit

country for the European market.

30

How is the trafficking conducted?

Despite reductions in production, the latest cocaine signa-

ture data indicates that most of the cocaine consumed in

the United States comes from Colombia.

31

The Colombian

government has been extremely successful in disassembling

the larger drug trafficking organizations, and this has

changed the nature of the market in the country. While

large groups like the Rastrojos and the Urabeños exist, they

are not powerful enough to threaten the state or eliminate

all interlopers. Rather, a free market exists in which a wide

range of players can source cocaine, and this is manifest in

the diversity of trafficking styles and techniques.

30 e Dominican Republic is by far the most frequent source of cocaine courier

ights to European destinations, and has recently been the source of some

large maritime shipments destined for Valencia, Spain.

31 United States Cocaine Signature Program

What is the nature of this market?

The history of cocaine trafficking from South America to

the United States has been well documented. The flow

peaked in the 1980s. During most of this time, Colombian

traffickers dominated the market, and they often preferred

to use the Caribbean as a transit area. Due to vigorous law

enforcement, the Colombian groups were weakened in the

1990s, and Mexican groups progressively assumed control

of most of the trafficking chain.

As a product of this shift, an ever-increasing share of the

cocaine entering the United States did so over the south-

western land border. Initially, direct shipments to Mexico

were favoured, with stopovers in Central America largely

Cocaine from South America to the United States

Figure 22: Number of primary cocaine move-

ments destined for, or interdicted in,

Central America, the Caribbean, and

Mexico, 2000-2011

Source: ONDCP

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Number of movements detected

Central America Mexico Caribbean

TransnaTional organized Crime in CenTral ameriCa and The Caribbean

32

Focused law enforcement in Colombia has also reduced the

number of shipments departing directly from the country.

Shipments by air mostly take off just across the border, in

Venezuelan territory. Shipments by sea are increasingly

embarking from Ecuador on the Pacific and the Bolivarian

Republic of Venezuela on the Atlantic. Until 2009, a large

share of the flights were destined for the Dominican

Republic, but much of this air traffic appears to have been

re-routed to Honduras after 2007, particularly following

the Zelaya coup in 2009.

Today, in addition to many minor sub-flows, there are three

main arteries for northward movement of cocaine:

• Pacic shing boats and other marine craft, including

semi-submersibles, particularly destined for Guatemala,

supplying cocaine to the Cartel del Pacíco.

• Atlantic go-fasts and other marine craft, including some

semi-submersibles, particularly destined for Honduras,

to supply both the Cartel del Pacíco and the Zetas.

• Aircraft, departing from the border area of the Boli-

varian Republic of Venezuela, particularly destined for

Honduras, supplying both the Cartel del Pacíco and the

Zetas.

Much has been made of the use of self-propelled semi-

submersibles (SPSS), and there have indeed been some

spectacular seizures, including recent ones off the coasts of

Honduras and Guatemala. These devices began as

submersed trailers off other vessels that could be cut loose

in the event of law enforcement contact, but they have

evolved considerably since then. True submarines have also

been detected, causing considerable alarm. But while the

potential for profit is great, so are the losses when an SPSS

is detected, and the Colombian government alone has

seized at least 50 of them. In addition to the cost of the

vessel, an SPSS usually carries multiple tons of cocaine,

costing US$10 million or more in Colombia. And SPSS are

generally very slow, so while they are hard to detect, there

is more time to detect them.

First detected in 1993, seizure of these vessels appears to

have peaked between 2007 and 2009, and to have declined

since. The United States government notes a reduction of

70% in the estimated use of SPSS between 2009 and

2010.

32

It may well be that traffickers are returning to more

traditional methods of moving their drugs. Go-fast boats, a

perennial favourite, seem to be making a comeback along

both coasts.

The use of aircraft, previously largely reserved for short

hops to the Caribbean, has also increased. Light aircraft

such as the Cessna Conquest and the Beechcraft Duke seem

to be preferred, but larger aircraft have been detected. They

may make several short hops between remote areas in

Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Guatemala.

These areas are often not accessible by road, and so rely on

small airstrips or jetties for all contact with the outside

world. Using both light aircraft and go-fast boats, cocaine

can be moved northward in an endless series of combinations,

touching down in areas the police rarely visit.

Panama

It is very difficult to traffic large volumes of cocaine by land

from Colombia, due to the Darien Strip, a near-impassible

stretch of jungle between the country and Panama. To

circumvent this barrier, some traffickers make the short sea

voyage to Panama from the Golf of Uraba on the Atlantic

(about 55% of the detected shipments) or Jurado on the

Pacific (45%). Traffickers simply wait for a break in the

security patrols before making the trip, using a wide range

of sea craft. On the Pacific side, this can involve rather slow

artisanal boats. Loads are consolidated in Panama, often in

areas inaccessible by road, before being shipped further

north.

Those who ply this leg are mainly Colombians and Pana-

manians, transportistas handling the cargo of others. The

country serves as both a storage and re-shipment zone.

Authorities estimate that perhaps 5% to 10% of the cocaine

entering the country is consumed locally, but although

Panama has the highest adult cocaine use prevalence in

Central America (reported to be 1.2% in 2003), this is dif-

ficult to believe given the huge volumes transiting the

country. Authorities also say as much as a third may eventu-

ally make it to Europe, often flowing via the Dominican

Republic, although local police only detected five Europe-

bound shipments in 2011. The bulk proceeds northward.

Larger shipments from the Bolivarian Republic of Vene-

zuela and Ecuador also transit Panamanian waters. Panama

routinely makes some of the largest cocaine seizures in the

world. Between 2007 and 2010, around 52 tons were seized

32 Oce of National Drug Control Policy, Cocaine Smuggling in 2010.

Washington, D.C.: Executive Oce of the President, 2012.

Figure 23: Number of primary cocaine move-

ments destined for, or interdicted in,

Honduras and the Dominican

Republic, 2000-2011

Source: ONDCP

0

50

100

150

200

250

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Number of movements detected

Dominican Republic Honduras

33

Cocaine from South America to the United States

per year– an average of a ton a week. Seizures in 2011 were

about 35 tons, but given that United States consumption

requirements are perhaps three times this, Panama’s seizures

alone continue to represent a significant source of supply

reduction. The loads also appear to have diminished in size

recently, from tons to a few hundred kilograms, perhaps

because traffickers can no longer afford losses that were

previously acceptable.

Costa Rica

The next country on the journey north is Costa Rica. The

number of direct shipments to Costa Rica has increased

remarkably in recent years, and between 2006 and 2010,

the country seized an average of 20 tons of cocaine per year,

compared to five tons between 2000 and 2005. More

recently, seizures have declined, but remain higher than

before 2006. The decline in seizures is difficult to explain,

as there does not appear to have been a commensurate

reduction in the number of direct shipments to the country.

Drugs making landfall in Costa Rica are reshipped by land,

sea, and air, with air becoming the predominant means in

recent years. There have also been significant recent seizures

(of amounts up to 300 kg) along the Panamerican Highway.

Large seizures have been made in Peñas Blancas, the main

border crossing point with Nicaragua in the northwestern

part of the country. In the south, the strategic zone of El

Golfito (the bay bordering Panama) and the border crossing

point of Paso Canoas are also used as storage points for

shipments heading north.

In addition to the northward traffic, Costa Rica has long

been a significant source of cocaine couriers on commercial

flights to Europe. This prominence seems to have decreased

in recent years, however.

Costa Rican coasts, both Pacific and Atlantic, are used by

traffickers to transport larger quantities of cocaine, through

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

)

)

)

)

)

Panama City

Colón

Chimán

Las

Perlas

Bocas

del

Toro

Isla Escudo

de Veraguas

\

\

\

Rio Belen

Rio Coclé

del Norte

Parque

Nacional Darien

Parque Nacional

Chagres

Parque Nacional

Cerro Hoya

Jurado

Colombia

Costa

Rica

Golfo

de

Uraba

Peninsula

de Asuero

San Blas

Veraguas

0 200100 km

Sea routes

B

Landing point

)

Storage point

\

City

\

Capital city

Panamerican Highway

National parks

Map 3: Cocaine trafficking routes in Panama

Source: UNODC, elaborated from interviews in the region

Figure 24: Distribution of cocaine seizures in

Central America, 2000-2011

Source: UNODC Delta Database

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Tons seized

El Salvador Guatemala Belize Honduras

Costa Rica Nicaragua Panama

TransnaTional organized Crime in CenTral ameriCa and The Caribbean

34

go-fast boats coming from Colombian sea ports, or

medium-sized boats (40 feet or less) and fishing vessels for

shorter trips. The Gulf of Punta Arenas and Puerto Quepos

on the Pacific coast are used as refueling stops for shipments

coming from Colombia and Panama. Seizures have been

made on the Atlantic coast at Puerto Limón, but they are

fewer in number than on the Pacific coast. Talamanca, a

remote area at the border with Nicaragua (and the region

where 80% of Costa Rica’s cannabis is produced

33

) is also

believed to be used for trafficking smaller quantities of

cocaine, with the involvement of indigenous communities.

33 Javier Meléndez Q., Roberto Orozco B., Sergio Moya M., Miguel López

R. Una aproximación a la problemática de la criminalidad organizada en las

comunidades del Caribe y de fronteras Nicaragua-Costa Rica-Panama, Instituto

de Estudios Etratégicos y Políticas Públicas. Costa Rica. August 2010.

Map 4: Cocaine trafficking routes in Costa Rica

Source: UNODC, elaborated from interviews in the region

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

)

)

)

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

(Colombia, Panama)

(Colombia, Panama)

(Colombia, Panama)

Liberia

San

José

Puntarenas

Paso

Canoas

Puerto

Limón

Puerto

Quepos

Peñas

Blancas

Cabo Blanco

Golfo

Dulce

Golfo de

Nicoya

Guanacaste

province

Nicaragua

Panama

Land routes

Sea routes

Air routes

B

Landing point

)

Storage point

\

City

\

Capital city

Panamerican Highway

0 10050 km

Figure 25: Cocaine seizures in Costa Rica (kg),

2000-2011

Source: Instituto Costarricense sobre Drogas

5,871

1,749

2,955

4,292

4,545

7,029

23,331

32,435

16,168

20,875

11,266

9,609

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

35,000

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Kilograms seized

Figure 26: Means of moving cocaine into Costa

Rica (in percent of detected

incidents), 2007-2010

Source: Instituto Costarricense sobre Drogas

66

32

71

78

23

59

20

17

11

9

9

6

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

2007 2008 2009 2010

Percent

Air Land Sea

35

Cocaine from South America to the United States

Map 5: Cocaine trafficking routes in Nicaragua

Source: UNODC, elaborated from interviews in the region

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

)

)

)

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

(Costa Rica,

Colombia, Venezuela)

Corn

Island

Cayos

Miskitos

Waspán

Walpasicsa

San

Andrés

Bluefields

Peñas Blancas

Managua

El Espino

Honduras

Costa Rica

El Salvador

Guatemala

Río Escondido

Río Grande

Río Wawa

Río Coco

B

Landing point

)

Storage/refueling point

\

City

\

Capital city

Air routes

Land routes

Sea routes

Fluvial routes

Panamerican Highway

0 10050 km

Nicaragua

While Nicaragua seizes impressive amounts of cocaine,

most of these seizures are made along the coasts, stretches

of which (particularly the Región Autónoma del Atlántico

Sur-RAAS/Región Autónoma del Atlántico Norte-RAAN

areas) are under-developed. The country remains primarily

a re-fuelling stop, and Nicaraguan traffickers are rarely

encountered outside their home country. Coastal

communities, including indigenous groups, provide logistic

support to traffickers, one of the few sources of income in

these isolated areas. Some may have a formal arrangement

with a particular transportista network, while others may

simply be capitalizing opportunistically from their

geographic location.

Many of these more remote areas are serviced by small

airstrips, since travel by road is impractical. These small

strips, combined with those in similar areas in Honduras,

allow cocaine to be moved northward in an almost endless

set of combinations of air, land, and sea transport. Although

most of the traffic is coastal, there does appear to be some

inland flow along the rivers, some of which transit more

than half the breadth of the isthmus.

The peripheral role Nicaragua plays in the trafficking is

reminiscent of the role formerly played by Central America

as a whole, and this has reduced the impact of the flow on

the country. Crime hardly plays a role in the political life of

Nicaragua, and its citizens are far more satisfied with their

country’s security posture than those in neighbouring

countries. Murder levels, though elevated, are stable.

El Salvador

El Salvador remains something of a puzzle. The authorities

claim that very little cocaine transits their country, because

they lack an Atlantic coast and pose few advantages over

countries further north. It is also true that El Salvador is the

most densely settled country in the region, reducing the

opportunities for clandestine airstrips and remote maritime

landings. Radar data suggest very few shipments from

South America proceed directly to El Salvador. Still, given

the fact that it borders both Honduras and Guatemala, it

seems likely that more cocaine passes through the country

than is sometimes claimed. This is suggested by the

September 2011 addition of El Salvador to the list of Major

Illicit Drug Transit countries by the United States

Government.

34

34 By Presidential Memorandum (Presidential Determination No. 2011-16)

dated 15 September 2011.

TransnaTional organized Crime in CenTral ameriCa and The Caribbean

36

Cocaine seizures are typically among the lowest in the

region, certainly on a per capita basis. The anti-narcotics

division seized less than seven kilograms in 2011, while the

United States estimates that four tons of cocaine transited

the country that year.

35

This is a product of the fact that

large seizures are rare, and that seizures of any size are made

rarely – less than 130 seizures were made in 2010.

36

The

police report that only “ant traffic” passes through the

country, with most shipments smaller than two kilograms.

Many of these seizures are made at El Amatillo, where the

Panamerican Highway crosses from Honduras into El

Salvador, the single best-controlled border crossing in the

country. At other border points, the police admit seizures

occur only with “flagrant” violations.

Given these conditions, it is not surprising that several

prominent transportista networks have been uncovered. The

Perrones network ran cocaine from one end of the country

to the other, with separate groups handling trafficking in

the east and west of the country. Although no seizures were

ever linked back directly to Reynerio Flores, it is unlikely

he dealt in quantities of less than two kilograms.

The Texis investigation, reported by journalists from the

35 By Presidential Memorandum (Presidential Determination No. 2011-16)

dated 15 September 2011.

36 ARQ 2010

Map 6: Cocaine trafficking routes in El Salvador

Source: UNODC, elaborated from interviews in the region

Golfo

de

Fonseca

Metapán

Acajutla

La Unión

El

Amatillo

San

Fernando

San Luis

La Herradura

San Salvador

Ostua

San Cristóbal

Frontera

La Hachadura

Las Chinamas

Honduras

Guatemala

Nicaragua

0 10050 km

Land routes

Sea routes

Landing point

City

Capital city

Panamerican Highway

Other routes

Figure 27: Number of cocaine hydrochloride

seizures in El Salvador, 2002-2010

Source: Annual Report Questionnaires

109

107

163

177

243

242

193

141

129

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

Number of seizures

on-line periodical El Faro, revealed a route whereby cocaine

is flown to rural Honduras or Nicaragua, and then flown

deeper into Honduras. It is then driven by road to El

Salvador, where Salvadoran traffickers bring it across the

northwestern corner of the country into Guatemala. This

flow, protected by high-level corruption and without direct

connections to violence, may have been tolerated for years,

and there does not appear to be an active investigation

today.

37

Cocaine from South America to the United States

The cocaine that enters the domestic market is believed to

be the product of “in kind” payment to transportista

networks. Many seizures of small amounts of crack are

evidence of this domestic market. Police claim that there is

a cocaine shortage in El Salvador, and that cocaine actually

travels back into the country from Guatemala. This is

demonstrated by the fact that prices for cocaine are often

higher in El Salvador than in Guatemala, although there

does not appear to be systematic price data collection.

The case of Juan María Medrano Fuentes (aka “Juan

Colorado”) demonstrates that commercial air couriering

also takes place. Until 2009, he ran a network of people

travelling three or four times a week carrying “nostalgia”

items to the Salvadoran expatriate community in the

United States, such as local cheese and bread. They were

also reportedly carrying cocaine.

37

There are also patterns of violence that are difficult to

explain except in terms of the drug trade. The violence is

particularly intense in the west of the country, especially

along several transportation routes radiating from the coast

and the borders. This concentration is suspicious, especially

given that it affects some lightly populated areas with

relatively low crime rates overall.

Cocaine as well as methamphetamine precursor chemicals

have been detected entering at the port of Acajutla on their

way to Guatemala, which is a short drive away through an

under-manned border crossing. This port is ideally situated

for traffickers looking to import discretely and cross an

international border quickly to evade detection. It is also

one of the more violent areas of the country, and one of the

few areas where it is alleged that certain mara members are

involved in cocaine trafficking.

Honduras

Today, Honduras represents the single most popular point

of entry for cocaine headed northward into Guatemala.

Honduras has a long history as a transit country, including

during the Civil Wars of the 1970s and 1980s, when it

represented a relatively safe means of getting cocaine to

Mexico through a dangerous region. Its use has waxed and

waned over time, but it is greater today than ever before.

Direct cocaine flows to Honduras grew significantly after

2006, and strongly increased after the 2009 coup. In

particular, air traffic from the Venezuelan/Colombian

border, much of which was previously directed to

Hispaniola, was redirected to airstrips in central Honduras.

According to the United States government, roughly 65 of

the 80 tons of cocaine transported by air toward the United

States lands in Honduras, representing 15% of United

States-bound cocaine flow.

38

Almost as much is moved to

37 See http://www.laprensagraca.com/el-salvador/judicial/78128-fgr-medrano-

enviaba-droga-via-encomienda.html

38 Oce of National Drug Control Policy, Cocaine Smuggling in 2010.

Washington, D.C.: Executive Oce of the President, 2012.

the country by sea. It takes just six hours by go-fast boat to

cross from Colombia to Honduras, and the brevity of this

route also allows the use of submarines. In the last year, at

least four submarines were detected around Honduras, and

seizures from just two of them amounted to about 14 tons

of cocaine.

Flights depart from the Venezuelan/Colombian border

heading north, before banking sharply and heading for

Honduras. Maritime shipments may unload at Puerto

Lempira, or another remote area of Honduras or northern

Nicaragua, before being flown further north in small

aircraft to other coastal areas, islands, or the provinces of

Olancho and Colón, or even into Guatemala. Once on

land, the drugs cross the border at both formal and informal

crossing points, although the formal crossings are generally

more convenient for the larger loads.

Figure 28: Clandestine airstrips detected in

Honduras, February-March 2012

Source: Armed Forces of Honduras

25

15

12

10

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Olancho Colón Gracias a Dios El Paraiso

Number of airstrips

The new “plazas”

Some of the most dangerous places in Central America

lie in a swath running between the northwestern coast

of Honduras and southwestern coast of Guatemala.

ere are hundreds of informal border crossing points

between the two countries, but, due to corruption and

complicity, it appears that most cocaine crosses at the

ocial checkpoints, such as Copán Ruinas/El Florido

(CA-11). Municipalities on both sides of the border

are aicted with very high murder rates, which is pe-

culiar given that these are mostly rural areas. Given the

competition between groups allied to the Zetas and the

Cartel del Pacíco, it is highly likely that these deaths are

attributable to disputes over contraband and tracking

routes.

TransnaTional organized Crime in CenTral ameriCa and The Caribbean

38

Map 7: Cocaine trafficking routes in Honduras

Source: UNODC, elaborated from interviews in the region and national police data

*Selected among the municipalities with highest homicide rates (<100 homicides per 100,000 population)

(Venezuela)

La Ceiba

Trujillo

Catacamas

Juticalpa

Puerto

Lempira

Tegucigalpa

Corinto

El Florido

San

Fernando

San

Pedro Sula

Agua

Caliente

El Espino

El Amatillo

Nicaragua

Guatemala

El Salvador

Belize

Olancho

Colón

Gracias a Dios

Cortés

Copán

Atlántida

Air routes

Land routes

Sea routes

Landing point

Storage/refuelling point

Most violent municipios*

City

Capital city

Panamerican Highway

Other roads

Departmental border

0 10050 km

Map 8: Cocaine trafficking routes in Guatemala

Source: UNODC, elaborated from interviews in the region and national police data

*Selected among the municipalities with highest homicide rates (<100 homicides per 100,000 population)

Mexico

Honduras

Belize

El Salvador

(Colombia)

Lago de

Izabal

Río Usumacinta

Cobán

Flores

Morales

Corinto

Anguiatú

El Carmen

Guatemala City

San Marcos

El Florido

Ingenieros

La Mesilla

El Progreso

Agua Caliente

Puerto Quetzal

Gracias a Dios

Puerto

Barrios

Melchor

de

Mencos

Ciudad

Tecún Umán

San Cristóbal

Frontera

Ciudad

Pedro de Alvarado

Escuintla

Zacapa

Land routes

Air routes

Sea routes

Fluvial routes

Landing point

Storage point

City

Capital city

Most violent municipios*

Secondary road

Panamerican Highway

0 10050 km

39

Cocaine from South America to the United States

Guatemala

When it comes to Central American cocaine trafficking, all

roads lead to Guatemala.

Traditionally, the country has been divided cleanly between

supply routes to the Cartel del Pacífico, which remains close

to the Pacific coast and depart the country primarily from

San Marcos, and those that supply the other groups, which

skirt the north of the country and leave through Petén.

Three seismic shifts appear to have precipitated the present

crisis. One is downward pressure from the Mexican security

strategy, which has virtually suspended direct shipments to

Mexico and forced as much as 90% of the cocaine flow into

the bottleneck of Guatemala. The second was the breakaway

of the Zetas from its parent, the Gulf Cartel. And the third

was the massive increase in direct shipments to Honduras.

Suddenly, dramatically increased volumes of cocaine were

crossing the border between Honduras and Guatemala,

greatly increasing the importance of the reigning crime

families there. As discussed above, the Mendoza crime

family in the north is currently aligned to the Cartel del

Pacífico and the Lorenzanas in the south are aligned to the

Zetas, which could create considerable friction as trafficking

routes intersect. The situation is complicated by the

geography of Guatemala, which does not allow a road

directly north from the Honduran border. Between the

border and Petén lies the Parque Nacional Sierra de la

Minas and Lake Izabal. To continue northward, one must

go east or west along CA-9:

• To the west, through Cobán, Alta Verapaz

• To the east, passing close to Morales, Izabal

The Zetas worked with local allies to secure control over

Cobán, causing the President to declare a state of emergency

in 2011. This temporary pressure may have encouraged the

Zetas to try the eastern route, but this runs directly into

Mendoza territory, turning northward not far from their

family home in Morales. All this seems to have contributed

to making the border area one of the most violent areas in

the world.

Belize and the Caribbean

Belize has long been a secondary route for cocaine, and has

diminished in popularity since 2006. The country has

participated in some important seizures, but most years, the

annual take is limited to some tens of kilograms. While the

country is highly vulnerable to trafficking groups with

access to resources exceeding national GDP, northward

movement is limited essentially to one road, with bottlenecks

at Belize City and Orange Walk. It is believed that the Zetas

are active in Belize, and seizures close to the border in

Mexico indicate increased trafficking. Some of this cocaine

may be entering from Guatemala in the north of the

country, crossing at Melchor de Mencos to Belize City.

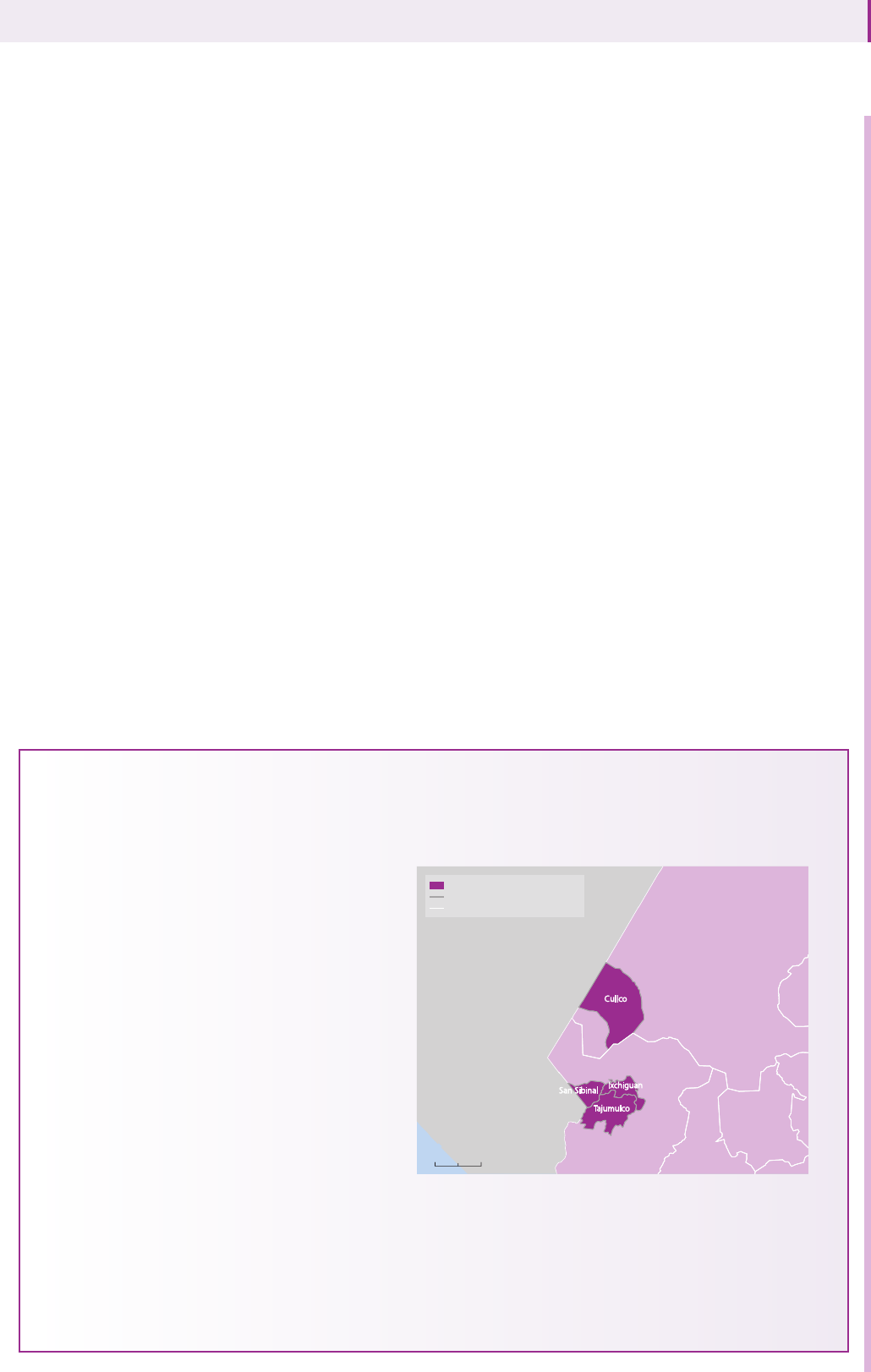

Opium poppy – Guatemala’s drug crop

While methamphetamine looms as a possible second,

at present the only drug produced in Central America

for export is opium poppy grown in western Guatemala.

e United Nations has never conducted a survey of

the extent of opium poppy cultivation in the area, but

eradication reported by the government suggest a grow-

ing problem. Between 2007 and 2011, poppy eradica-

tion in Guatemala tripled, from less than 500 hectares

eradicated in 2007 to more than 1500 hectares in 2011.

Eradication is concentrated in two departments and

four municipalities in the western part of the country:

San Marcos (Ixchiguán, Sibinal, Tajumulco) and Hue-

huetenango (Cuilco). e Cartel del Pacíco is the group

most associated with heroin tracking, and San Marcos

is home to its ally, Los Chamales.

Since 2007, Guatemala has surpassed Colombia with

regards to opium poppy eradication and is now second

only to Mexico. According to the Ministerio de Gob-

ernación, the eradication only represents 10% of the

cultivation, which would suggest a total area of cultiva-

tion of approximately 15,000 hectares, close to the estimated opium poppy-growing area in Mexico. Lack of clarity around the

cultivation area, yields, and quality makes any estimate highly dubious. It is also unclear where this output would be consumed.

In the past, opium was tracked across the border for processing, as evinced by the seizure of opium poppy capsules in transit.

But today, it seems likely that some heroin is made in Guatemala, particularly given the increased seizures of precursor chemicals.

Map 9: Opium poppy eradication in

Guatemala, 2011

Source: UNODC, elaborated with data from the Policía Nacional Civil

(Guatemala)

Huehuetenango

San Marcos

Mexico

02010 km

Opium poppy field eradication

Departmental boundary

Municipal boundary

TransnaTional organized Crime in CenTral ameriCa and The Caribbean

40

The Caribbean used to be the primary conduit for cocaine

trafficking to the United States, and there is always the risk

that it could become so again. Enhanced monitoring of

both air and sea traffic along the United States coastline has

made this more difficult than in the past, however. The

Caribbean does play a role in trafficking to Europe, but

much of this flow is maritime, and the drugs never need

make landfall on Caribbean soil.

Hispaniola, and the Dominican Republic in particular, saw

a resurgence in popularity as transshipment points between

2006 and 2009, in the period between the implementation

of the new security strategy in Mexico and the coup in

Honduras. Opportunities in Central America, teamed with

stronger enforcement in the Dominican Republic, have

caused this flow to dwindle over the last two years. Seizure

figures were up in 2009 and 2010, but this appears to

represent a higher rate of interdiction, not a greater flow.

Dominican traffickers have long been close partners of the

Colombians in moving cocaine to the United States and in

distributing it in the northeast of the country. The

Dominican Republic is also a popular destination for

tourists from Europe and a large European expatriate

community resides there. These factors placed Dominican

traffickers in a favourable position when cocaine use in

Europe began to grow during the 2000s.

Today, the Dominican Republic is the primary source in

the region of cocaine smuggled on commercial air flights to

Europe. The number of air couriers detected on flights

from the region in one European airport database

quadrupled between 2006 and 2011.

39

This does not

necessarily indicate an increase in flow, since the amounts

trafficked by this means are small. Dominican citizens are

also the most prominent nationality in the region among

those arrested for cocaine trafficking in Europe.

Jamaica was once a key transit country for both the United

39 IDEAS database. e IDEAS database is a product of voluntary information

sharing between a number of European airports. It is not a representative

sampling of all European airports.

States and the United Kingdom but has declined

considerably in importance since its heyday. The Jamaican

example illustrates that the removal of a drug flow can be

as destabilizing as its inception. Estimates of the cocaine

flow through Jamaica dropped from 11% of the United

States supply in 2000 to 2% in 2005 and 1% in 2007.

40

This is reflected in declining seizures in Jamaica and

declining arrests and convictions of Jamaican drug traffickers

in the United States.

41

The impact of this decline in flow is

discussed in the final sections of this report.

Both the Dutch Caribbean and the French Caribbean have

become important conduits for cocaine destined for

Europe. During the early 2000s, huge numbers of couriers

40 Statement of the Donnie Marshall, Administrator, United States Drug

Enforcement Administration before the United States Senate Caucus on

International Narcotics Control, 15 May 2001; National Drug Intelligence

Centre, National Drug reat Assessment 2006. Washington, D.C.:

Department of Justice, 2006; National Drug Intelligence Centre, National

Drug reat Assessment 2007 Washington, D.C.: Department of Justice,

2007; National Drug Intelligence Centre, National Drug reat Assessment

2009. Washington, D.C.: Department of Justice, 2009.

41 In 2000, the United States federal authorities convicted 79 Jamaicans for

cocaine tracking. In 2008, they arrested just 35. In 2010, not one was

arrested.

Figure 29: Kilograms of cocaine seized in the

Dominican Republic, 2000-2010

Source: UNODC Delta

1,307

1,908

2,293

730

2,232

2,246

5,092

3,786

2,691

4,652

4,850

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

Kilograms seized

Figure 30: Breakdown of the origin of detected

cocaine shipments on commercial

flights to selected European airports

from Central America and the Carib-

bean in 2011

Source: IDEAS database

Dominican

Rep, 110

French

Caribbean,

21

Mexico, 21

Other, 9

Costa Rica,

5

Figure 31: Kilograms of cocaine seized in

Jamaica, 1992-2011

Source: UNODC Delta

690

83

179

570

254

415

1,143

2,455

1,656

2,948

3,725

1,586

1,736

142

109

98

266

2

176

552

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

3,000

3,500

4,000

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Kilograms seized

41

Cocaine from South America to the United States

landed at Schiphol airport, overwhelming the capacity of

the Dutch legal system to process them. Recognizing that

the couriers were much less important to the traffickers

than the drugs, the Dutch began seizing the drugs from all

suspected couriers and sent them home with blacklisted

passports. The intervention worked, and the airflow

diminished remarkably.

42

The French Caribbean only really became an issue after

Francophone West Africa became part of the cocaine

trafficking chain. France itself consumes relatively little

cocaine, so it did not become an important port of entry

until cocaine landed in West Africa, and the main

commercial air routes happened to be linked to France.

Today, the French overseas departments are some of the

main sources of air couriers detected in Europe. Located in

South America but with cultural connections to Europe,

“the Guyanas” (Guyana, French Guiana, and Suriname) are

also important in the European flow, but much less so to

the United States.

Who are the traffickers?

Most of those arrested for drug trafficking in Central

America are citizens of the country in which they were

arrested. Globally, this is not always the case, and suggests

that each country has its own network of traffickers and

transportistas, carrying the drug from one border to another.

But the type of people involved in trafficking varies sharply

between countries. As the drugs move northward, the range

of alternative routes narrows, and the competition becomes

more fierce. As a result, Honduran and Guatemalan groups

compete to control territory, while those further south are

primarily transportistas and their foes.

In Guatemala and Honduras, the territorial nature of drug

trafficking has given special importance to land ownership,

and many large landholders, including commercial farmers

and ranchers, are prominent among the traffickers. Planta-

tions and ranches provide ground for clandestine landing

strips and cocaine storage facilities. They also provide sites

for training and deploying armed groups, and plausible

cover for large groups of men operating in remote areas of

these countries. Guatemalan landholders have long

employed “private security companies” to oversee their

agricultural labourers, so the sight of armed men in pick-up

trucks is not unusual. Profits from drug trafficking can be

passed off as the proceeds of productive farms and ranches.

These groups are also more likely to invest in buying polit-

ical influence beyond paying off the local border guards.

Outside of Guatemala and Honduras, most of those

involved in the cocaine trade appear to be transportistas or

tumbadores. In Panama, the tumbador problem is particularly

42 For a more detailed discussion of this intervention, see Chapter 7 of World

Bank and UNODC, Crime, Violence, and Development: Trends, Costs and

Policy Options in the Caribbean. Washington, D.C., World Bank, 2007.

acute, but it is also an issue in Honduras and Guatemala.

Tumbadores tend to strike when the drugs are on land,

especially in the urban areas they dominate.

Panama

Transportista groups in Panama are primarily comprised of

Panamanian and Colombian nationals. In addition to

cocaine lost to the state, these transportistas also lose an

unknown share to tumbadores. There are perhaps 40 to 50

tumbador factions (though some sources place the number

much higher), each with about a dozen men. Some

charismatic leaders have managed to unify several gangs

into larger units, but more often these groups are locked in

conflict over trafficking areas.

One of the most notorious tumbador groups is under the

leadership of “Cholo Chorrillo” (“El Cholo”), who managed

to merge three juvenile local gangs into one organization,

dedicated to drug theft and extortion from other trafficking

groups.

43

Much of the violence in Panama City is caused by

a conflict between two opposing tumbador groups from

different areas of the city – one led by a famous tumbador

called “Moi” and the other one by his rival “Matagato”.

Costa Rica and Nicaragua

Most of the cocaine touching Costa Rica and Nicaragua

tends to do so along the periphery, so domestic groups are

not a big issue. In Costa Rica, several transportistas from

Guatemala and Nicaragua have been recently arrested at

border points with Nicaragua, in particular in Peñas Blancas

on the Panamerican Highway, carrying consignments of

several hundred kilograms. All evidence suggests, though,

that transportation along the southern portions of the

Panamerican Highway is a relatively minor trafficking

route.

It would require an attenuated definition of “organization”

to include the many people who provide support to the

traffickers along the coasts. Many of these communities are

43 e groups were Bagdad from Chorrillo; El Pentágono from Santa Ana; and

“El MOM (Matar or Morir)” from Curundú.

Figure 32: Number of arrests for drug trafficking

in Costa Rica, 2006-2011

Source: Instituto Costarricense sobre Drogas

1,205

994

1,027

1,345

1,518

1,647

0

200

400

600

800

1,000

1,200

1,400

1,600

1,800

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

Number of arrests

TransnaTional organized Crime in CenTral ameriCa and The Caribbean

42

indigenous, and are simply providing food and fuel to some

well-heeled visitors. But there are others who are fully

cognizant of what is going on, and provide both security

and information to the transportistas. They may even

provide offloading and storage services if required.

Cocaine trafficking arrests in Costa Rica have increased

significantly in recent years. The majority of those arrested

for cocaine trafficking were Costa Rican, but only just. A

significant number of Mexicans and Colombians were

detected. For example, in January 2011, Costa Rican

authorities dismantled an organization of five Colombians

and one Costa Rican in charge of coordinating maritime

shipments of cocaine from Colombia and Ecuador to Gua-

temala and Mexico. In February 2011, three Mexicans were

arrested in El Guarco (south of San José) with more than

300 kg of cocaine.

El Salvador

Much has been made of the ongoing activities of the

Perrones transportista network, a group that the state claims

to have dismantled some time ago. In 2007 and 2008, a

number of high profile members were targeted, including

dozens of police officers from the Anti-Narcotics Division.

The arrest of the putative leader of the Perrones, Reynerio

de Jesús Flores Lazo, in 2009 was considered by many to be

the decisive blow to the organization, but others contend

that it continues to operate in the country. The investigation

of the Cartel de Texis uncovered high-level corruption, and

opens the possibility that there are other such networks

operating undetected in the country.

But there have been no claims that territory-dominating

groups are present in El Salvador. There have been claims

of mara involvement in moving some medium sized

shipments in the southwest of the country, but all other

known groups are mere transportistas. As a result, El

Salvador’s sustained high levels of violence cannot easily be

tied to transnational drug trafficking.

Honduras

In Honduras, several territorial groups are working for

Colombian (in Atlántida) and Mexican (in Olancho, La

Ceiba, and Copán) drug trafficking organizations. Some

tumbador-style groups, known as “los grillos,” have also been

reported in the country, in particular in the area of La

Ceiba.

As in Guatemala, land-owners and “rancheros” are involved

in trafficking activities, particularly in border areas that

they control. Some municipalities in the northwest part of

the country (in Copán, Ocotepeque, Santa Bárbara) are

completely under the control of complex networks of

mayors, businessmen and land owners (“los señores”)

dedicated to cocaine trafficking. “El Chapo” Guzmán has

also been reported to be travelling to this part of the country

(Copán), so groups here may be connected to the Cartel del

Pacífico, but the violence in this area suggests that control

is contested.

Guatemala

Traditionally, much of Guatemala has been governed

locally, with few services provided by the central state. In its

place, large landholders and other local authorities saw to

the provision of basic civic services and were allowed to

operate with relatively little interference. When civil war

broke out in the 1960s, the situation changed, with the

military eventually extending state authority to every corner

of the country and every aspect of political and economic

life.

In the more remote areas of the country, the liaison between

the military units and local community was a civilian offi-

cial known as a “Military Commissioner”. Drawn from the

local community, these Commissioners wielded tremen-

dous power, acting as the eyes, ears, and right hand of the

military commanders. Large-scale cocaine trafficking began

to pass through Guatemala in the 1980s, at the peak of

military control. The Commissioners were clearly complicit

in that traffic.

Under the peace accords, the military was downsized

considerably, and the more remote areas reverted back to

their traditional ways. Many retired officers began to focus

on business interests they had developed during the war.

These officials had strong ties to the government and their

former colleagues in the military, allowing them to operate

with impunity. And the former Commissioners, who

continued to wield power in their home areas, read like a

who’s who list of drug trafficking: Juancho León, Waldemar

Lorenzana, and Juan “Chamale” Ortiz.

44

44 Espach, R., J. Melendez Quinonez, D. Haering, and M. Castillo Giron,

Criminal Organizations and Illicit Tracking in Guatemala’s Border

Communities. Alexandria: Center for Naval Analyses, December 2011, p. 12.

Figure 33: Nationalities of people arrested for

cocaine trafficking in Costa Rica in

2010

Source: Instituto Costarricense sobre drogas

Costa Rica

56%

Mexico

13%

Nicaragua

10%

Other

10%

Colombia

7%

Guatemala

3%

Panama

1%

43

Cocaine from South America to the United States

Belize and the Caribbean

Belize has been cited many times as a possible refuge for

Guatemalan traffickers on the run, and some have been

apprehended there. Still, the navigable territory for drug

trafficking is limited. The country is, however, a site for

money laundering and, as it has not ratified the Convention

on Psychotropic Substances of 1971, the import of precursor

chemicals.

In the Caribbean, Dominican traffickers appear to be the

single most active national group. There are significant

Dominican communities in Spain and the Northeastern

United States, and a good number of Dominicans have

been arrested in both countries for drug trafficking.

Jamaican traffickers used to be much more prominent than

they are today.

How big is the flow?

The United States has recently generated detailed estimates

of the amount of cocaine that transited the landmass of

each Central American country in 2010.

45

Cocaine proceeds

by air and sea, and the amount making final landfall grows

as the flow moves northward. The exceptions are El Salvador

and Belize, which, according to the United States, are

mainly circumvented because the northward land flow

proceeds through Honduras and Guatemala. According to

these estimates, 330 tons of cocaine left Guatemala and

entered Mexico in 2010, with 267 tons of this having

previously transited Honduras, and so on down the line.

Converted to wholesale values at local prices, the values of

these flows range from more than US$4 billion in Guatemala

to just US$60 million in El Salvador. Relative to the local

economy, this flow represents a remarkable 14% of the

GDP of Nicaragua, while representing a rather small

amount relative to the sizes of the economies of Panama

and El Salvador.

Implications for responses

The discussion above has highlighted several points about

the mechanics of the cocaine flow that are relevant when

formulating policy:

• ough diminishing, the value of this ow is still very

large in proportion to the economies of the countries

through which it ows. For example, the wholesale val-

ue of the cocaine passing through Guatemala, if sold on

local markets, would be over US$4 billion, more than

the US$3 billion the entire region spent on the ght

against crime in 2010. Not all of this accrues to traf-

ckers in Central America, but if even one-tenth of the

local wholesale value remained in the region, the impact

would be enormous. Disproportionate economic power

gives trackers great leverage in both sowing corruption

and fomenting violence.

45 Oce of National Drug Control Policy, Cocaine Smuggling in 2010.

Washington, D.C.: Executive Oce of the President, 2012.

Figure 34: Tons of cocaine transiting the land-

mass of Central American countries

in 2010

Source: ONDCP

330

267

140

128

80

10

5

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

Guatemala

Honduras

Nicaragua

Costa Rica

Panama

Belize

El Salvador

Tons of cocaine transiting

Figure 35: Value of cocaine transiting Central

American countries (US$ millions),

2010

Source: Elaborated from ONDCP and UNODC data

4,046

1,949

910

896

200

74

60

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

3,000

3,500

4,000

4,500

Guatemala

Honduras

Nicaragua

Costa Rica

Panama

Belize

El Salvador

US$ millions

Figure 36: Share of GDP represented by value of

cocaine transiting each country, 2010

Source: Elaborated from ONDCP and UNODC data

14

13

10

5

3

1

<1

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

Nicaragua

Honduras

Guatemala

Belize

Costa Rica

Panama

El Salvador

Percent of GDP

TransnaTional organized Crime in CenTral ameriCa and The Caribbean

44

• e ow is uid, adapting with ease to any blockages

encountered. is is illustrated by the extremely rapid

manner in which trackers took advantage of the post-

coup chaos in Honduras, re-routing their shipments vir-

tually overnight to take advantage of the opportunity.

ey predictably take the path of least resistance, and

local allies appear to be easily replaced.

• Despite the ability of trackers to adapt to sudden

changes, shifts in the ow can be devastating for the

transit areas, both those abandoned and those newly in-

volved. Violent contests for access to cocaine revenues

are predictable whenever tracking patterns change,

whatever the reason for the change.

• Much of the ow, particularly in the southern states of

Central America, proceeds by air and sea between areas

not connected by road to the major population cent-

ers. On the one hand, this is a good thing – the use

of remote stopover points minimizes the impact of the

drug ow on the countries aected. On the other, this

technique makes enforcement challenging, because law

enforcement agencies rarely visit the areas where the

drugs are transiting.

The discussion above highlights the fact that two issues

often amalgamated – the cocaine flow and organized crime

related violence – are distinct, and need to be addressed

separately. At the same time, the two problems are

sufficiently interrelated that each policy line needs to take

into account the other. In particular, interventions that

affect cocaine trafficking can produce negative outcomes in

terms of violence. These outcomes need to be planned for

and buffered by all available means.

The problem today is that the flow has become concentrated

in the countries least capable of dealing with its presence.

Unless these areas become inhospitable, the traffickers will

become entrenched, using their economic weight to deeply

infiltrate communities and government structures. This

slow incursion is less dramatic than the violence associated

with enforcement, but it is far more devastating in the long

term. Cocaine trafficking is not a problem that can be

solved through passivity.

The countries of Central America do not have the resources

to deal with this problem on their own, and they should not

be expected to do so. The flow originates and terminates

outside the region. The international community should

provide these countries its full support in dealing with what

is truly a transnational problem.

Methamphetamine

Cocaine is the primary focus of virtually every

drug tracking organization in Central America,

but given the inuence of the Cartel del Pacíco in

San Marcos and the south of Guatemala, it is not

surprising that methamphetamine has become

an issue. e supply of methamphetamine to

the United States has long been a specialty of the

“Sinaloa Cartel” and its successors, although this

dominance was interrupted when it lost the port

of Lázaro Cárdenas to former ally La Familia and

its splinter, the Knights Templar (Los Caballeros

Templarios). Since then, there has been increasing

transshipment of precursor chemicals and meth-

amphetamine to Mexico from Guatemala.

More recently, large volumes of precursor chemi-

cals have been found owing the opposite di-

rection, suggesting that methamphetamine

manufacture has been relocated to Guatemala. A

number of labs have been discovered in San Mar-

cos and near the Mexican border, and hundreds

of thousands of liters of precursor chemicals have

been seized, especially in Puerto Barrios, in the

territory of the Mendoza family, a Cartel del Pací-

co ally. Major seizures of precursor chemicals

have also been made in El Salvador, Honduras,

Belize, and Nicaragua.

Precursor chemical seizures in Guatemala in 2012

Date Barrels Chemical Location Origin

2 Jan

160

(33,264 L)

Dimethyl-

maleate

Puerto Barrios,

Izabal

China

3 Jan

65

(13,513 L)

Acetone

La Libertad,

Petén

5 Jan

761

(158,212 L)

Unspecified

Puerto Barrios,

Izabal

China

10 Jan

320

(66,736 L)

Marked as

noniphenol

Puerto Barrios,

Izabal

Shanghai,

China

11 Jan

320

(66,736 L)

Marked as

noniphenol

Puerto Barrios,

Izabal

Shanghai,

China

16 Jan

66

(13,720 L)

Methylamine Guatemala City

17 Jan

131

(27,240 L)

Methylamine Guatemala City

17 Jan

240

(49,900 L)

Monomethyl-

amine, ethyl

phenyl acetate

Puerto Barrios,

Izabal

8 Feb

80

(16,353 L)

Unspecified

El Caco, Puerto

Barrios, Izabal

April 80,000 L Unspecified

En route to Hon-

duras

China

Source: National Police of Guatemala