GISP

Global Invasive Species Programme

United States Government

Invasive Alien Species

in the Austral-Pacific Region

National Reports

&

Directory of Resources

Edited by Clare Shine, Jamie K. Reaser, and Alexis T. Gutierrez

2

The report is a product of a workshop entitled, Prevention and Management of Invasive Alien Species: Forging

Cooperation throughout the Austral Pacific. The meeting was held by the Global Invasive Species Programme

(GISP) in Honolulu, Hawai'i on 15-17 October 2002. It was sponsored by the U.S. Agency for International

Development, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on behalf of the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force, U.S.

Department of the Interior - Office of Insular Affairs, U.S. Department of State, and The Nature Conservancy. In-

kind assistance was provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Administrative and logistical

assistance was provided by the Bishop Museum, Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment, and the

National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. The Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History

provided support during report production.

The workshop was co-chaired by Drs. Allen Allison and William Brown (Bishop Museum), Mr. Michael Buck

(State of Hawai'i, Division of Forestry & Wildlife), and Dr. Jamie K. Reaser (Global Invasive Species

Programme; GISP). The members of the Steering Committee included: Dr. Maj de Poorter (ISSG), Ms. Liz Dovey

(SPREP), Dr. Lucius Eldredge (Bishop Museum), Ms. Alexis Gutierrez (GISP), Dr. Laura Meyerson

(GISP/USEPA), Dr. Jamie K. Reaser (GISP), Dr. Dana Roth (U.S. Department of State), and Dr. Greg Sherley

(New Zealand Department of Conservation).

The report of the workshop has been published by GISP (see address below) as: Shine, C., J.K. Reaser, and A.T.

Gutierrez. (eds.). 2003. Prevention and Management of IAS: Proceedings of a Workshop on Forging Cooperation

throughout the Austral-Pacific. Global Invasive Species Programme, Cape Town, South Africa.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of any

government or other body represented in the meeting, nor its sponsors.

Published by: The Global Invasive Species Programme

Copyright: (c) 2003 The Global Invasive Species Programme

Reproduction of this publication for education or other non-commercial purposes is authorized

without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully

acknowledged. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior

written permission of the copyright holder.

Citation: Shine, C., J.K. Reaser, and A.T. Gutierrez. (eds.). 2003. Invasive alien species in the Austral

Pacific Region: National Reports & Directory of Resources. Global Invasive Species

Programme, Cape Town, South Africa.

Contact: Global Invasive Species Programme

National Botanical Institute

Kirstenbosch Gardens

Private Bag X7

Claremont 7735, Cape Town

South Africa

Tel: +27 21 799 8800

Fax: +27 21 797 1561

www.gisp.org

3

Preface

This report is one of three products of a workshop entitled, Prevention and Management of Invasive

Alien Species: Forging Cooperation throughout the Austral Pacific. The meeting was held by the

Global Invasive Species Programme (GISP) in Honolulu, Hawai'i on 15-17 October 2002. The other

products include a regional statement on IAS and a workshop report (also downloadable from

www.gisp.org

). This document is the first country-driven effort to assess the status of invasive alien

species (IAS) and share information on IAS national programs in the Austral Pacific region.

Each country that participated in the regional workshop was invited to submit a chapter that included

information on known IAS, existing strategies for preventing and managing IAS, objectives and contact

information for departments/ ministeries concerned with IAS, priorities for future work on IAS, list of

in-country IAS experts, and a list of relevant references and websites.

Participants were asked to provide information relevant to both agriculture and environmental sectors

and to work across multiple ministeries when possible. The ability of each country to provide this

information varied considerably and depended upon the amount of information already available IAS

problems for their country, existence of within country technical expertise, and how high a priority the

IAS issue is for the government at this time. A few delegations were not able to make contributions to

this document, and are in the process of assessing the status of IAS in their countries.

The data provided within this document reflects the most up-to-date information available to the authors

of each country report at the time of writing. These authors and the GISP make no claim that this

information is complete or scientifically accurate (e.g. scientific names may not always have been

correctly assigned to non-native species). However, the authors and editors have made every effort to

ensure as useful and reliable a document as possible.

GISP hopes that this document will be seen as a foundation for future work on IAS within the Austral

Pacific region. Readers who are able to provide additional information or updates to specific chapters

are strongly encouraged to contact the authors as well as GISP. This report is also downloadable from

www.gisp.org

and, if new information warrants, will be updated as appropriate.

Reports arising from GISP’s workshops in other regions of the world are also available at

www.gisp.org

.

4

The Austral-Pacific Region

The Austral-Pacific region has numerous characteristics that make information sharing and other

aspects of regional coordination on invasive alien species (IAS) issues particularly important. For

example, 98% of its 30 million km

2

is ocean; the remaining 2% contains 7500 islands, of which just 500

are inhabited. Many islands in the three subregions - Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia - are small

and widely scattered. Whereas the ocean once provided a natural barrier against the spread of pests and

diseases, the rapid expansion of trade, travel, and transport now make the region particularly vulnerable

to the devastating impacts of IAS. Furthermore, Pacific islands share trading routes, partnerships, and

regional infrastructure, which can increase opportunities for introduction of IAS. The inhabitants of the

Austral-Pacific region, therefore, have a mutual interest in preventing and managing IAS at the point of

export and import.

Map of the Austral Pacific region

.

Credit: Courtesy of Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin

5

National Reports & Directory of Resources on IAS

Contents

Preface 3

The Austral Pacific region and map 4

Contents 5

Australia – no report submitted 6

American Samoa 7

Cook Islands 11

Fiji – no report submitted 21

French Polynesia 22

Guam 35

Hawai'i 46

Marshall Islands 51

Micronesia, Federated States of 61

Nauru 62

New Zealand 63

Niue 77

Northern Mariana Islands, Commonwealth of the 84

Palau, Republic of 102

Samoa – no report submitted 165

Solomon Islands 166

Tokelau 170

Tonga, Kingdom of 175

Tuvalu – no report submitted 178

Vanuatu

179

6

Australia

No report has been submitted.

The delegate to the GISP Austral-Pacific Workshop was:

Mr. Warren Geeves

Introduced Marine Pest Program

Marine and International Section

Marine and Water Division

Environment Australia

Tel: 61 2 6274 1453

Fax: 61 2 6274 1006

Email:

7

American Samoa

Mr. Manu Tuionoula

Department of Agriculture

P.O. Box 6997, Pago Pago,

American Samoa 96799

Tel: 684-699-5731

Fax: 684-699-4031

E-mail:

Introduction

American Samoa is a group of oceanic islands, which lie about 3,680 km southwest of Hawai’i and

about 2,560 km from the northern tip of New Zealand. It is situated along 14 degrees latitude south of

the equator. Its immediate neighbor is Samoa (formerly known as Western Samoa), an independent

state 128 km to the west. The total land area of American Samoa is about 200 square kilometers, which

is shared by five main islands, namely Tutuila, Tau, Ofu, Olosega, and Aunuu. The climate is tropical

humid, with an annual rainfall ranging from 3,175 mm at sea level to more than 7,000 mm on the

highest mountain, Lata on Tau island.

1. Main IAS in American Samoa

American Samoa has numerous alien species, some of which were introduced into the territory many

decades ago for various purposes, including food, biological control, medicine, ornamental purposes,

and conservation. Other alien species were either smuggled in, or unintentionally introduced through

trade.

Like other Pacific Island countries and territories (PICTS), American Samoa is vulnerable to the effects

and changes caused by invasive alien species (IAS). After habitat destruction or modification, whether

by natural disaster or by man, IAS seem to be more prolific and may have caused the reduction or even

extinction of other species. Some of these species have threatened to destroy American Samoa’s

biological heritage and have adversely affected agricultural production and natural ecosystems, leading

to economic and ecological losses.

A list of American Samoa’s most harmful invasive or pest species with economic or ecological impacts

includes:

⇒

Fungi

- Taro leaf blight (Phytophthora colocaisae), which wiped out the taro industry of both Samoas

in 1993-1994

- Black leaf streak of banana (Mycosphaerella fijiensis)

⇒

Insects

- Cluster caterpillar (Spodoptera litura) (Lepidoptera) (Noctuidae)

- Cotton aphid (Aphis gossypii) (Hemiptera) (Aphididae)

- Rhinoceros beetle (Oryctes rhinoceros) (Coleoptera) (Scarabaeidae)

- Fruit piercing moth (Othreis fullonia) (Lepidoptera) (Noctuidae)

- Diamond back moth (Plutella xylostella) (Lepidoptera) (Yponomeutidae)

8

⇒

Snails

- African snail (Achantina fulica) (Achantinidae)

⇒ Birds

- Common myna bird (Acridotheres tristris)

- Jungle myna bird (Acridotheres fuscus)

- Red vented bulbul (Pycnonotus cafer).

These three species are believed to cause population reduction of some local bird species, as well as

damage to some fruit trees and vegetables.

⇒

Plants

- Sedge (Cyperus rotundus) (Cyperaceae)

- Grass (Paspalum conjugatum) (Poaceae)

- Koster’s curse (Clidemia hirta) (Melastomataceae)

- Molucca albizia (Paraserianthes falcataria) (Fabaceae)

- Broad leaf vine (Merremia peltata) (Convolvulaceae): This has prohibited the re-growth of

some local tree species which were devastated by the two great hurricanes of 1990 and 1991.

2. Summary of existing strategies and programs on IAS

American Samoa established a National Task Force on IAS in 2003. The first and most important step

involved an agreement between the directors of the Department of Agriculture and the Department of

Marine and Wildlife Resources to create such a joint force. This proposal was submitted to the governor

and received formal approval early in 2003.

Routine programs for dealing with all alien species (known and potential invasives as well as non-

invasives) entering the territory are still carried out by the Quarantine Division of the Department of

Agriculture, in cooperation with other government departments (see 3 below).

In the National Park of American Samoa, an invasive plant management programme has been

established (see 4 below).

3. Government departments/agencies concerned with IAS

Primary responsibility for dealing with all alien species (both invasive and non-invasive) entering the

territory lies with the Quarantine Division of the Department of Agriculture. Quarantine officers are at

the frontline in controlling all ports of entry and work closely with the Plant Protection Division and

Veterinary Service to evaluate which species should be allowed into the country, prior to issuing

permits. Marine and wildlife matters are referred by quarantine officers to the Department of Marine

and Wildlife Resources whenever there is a relevant interception.

The Office of Samoan Affairs may also be involved in IAS prevention and management issues.

Specific responsibilities for IAS prevention, management and/or control are as follows:

9

⇒

Department of Agriculture

Quarantine Division: carries out border inspection to ensure that species entering the country are

permitted by law.

Plant Protection Division: advises the Quarantine Division on plant species that should be allowed

into the country, and monitors and controls invasive plant species in residential areas, farm lands,

and forests.

Veterinary Service: advises the Quarantine Division on animals and animal products that should be

permitted into the country, and monitors and controls invasive animal pests present in the country.

Contact Information

Director,

Department of Agriculture,

American Samoa Government,

Pago Pago, American Samoa 96799

Tel: (684) 699 1497

(684) 699 9272

Fax: (684) 699 4031

Email: [email protected]

⇒

Department of Marine and Wildlife Resources

Marine Division: monitors and manages all marine resources, including IAS, and enforces marine

harvesting legislation.

Wildlife Division: monitors and manages wildlife in the forest and enforces wildlife legislation.

Contact Information

Director,

Department of Marine and Wild Life Resources,

American Samoa Government,

Pago Pago, American Samoa 96799

Tel: (684) 633 4456

Fax: (684) 633 5944

⇒

Office of the National Park of American Samoa

This Office is responsible for the management and control of all species in the park area. Its mission

is to preserve Samoan culture, save and protect mixed species old growth forest and protect

ecosystems, including the coral reefs and marine components of the Park. An invasive species

programme has been established. This involves students and the community in addressing invasive

plant problems and reviving traditional cultural practices and language relevant to native heritage

plants and their uses.

10

Contact Information

Superintendent,

National Park of American Samoa,

Pago-Pago, American Samoa 96799

Tel: (684) 633 7082

Fax: (684) 633 7085

4. Priorities identified for future work

⇒

Preventing the entry of IAS and of alien species with the potential to become invasive.

⇒

Thorough assessment of alien species already present on the islands as part of the development of a

national strategy.

⇒

Public awareness and educational programmes.

⇒

Where possible, eradication of IAS.

5. List of experts working in the field of biological invasions

No information provided.

6. Bibliographic references

Gerlach, W. 1988. Plant diseases of Western Samoa. Samoan German Crop Protection Project, Apia,

Western Samoa.

Pacific Island Ecosystems at Risk (PIER). Report on invasive plant species in American Samoa. CD-

Rom available from Pacific Island Ecosystems at Risk (http://www.hear.org/pier/index.html

)

South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP). 2000. Invasive species in the Pacific: A

technical review and draft regional strategy. South Pacific Regional Environment Programme,

Samoa.

Tuionoula, M. and T. Uele. 1993. Report on taro leaf blight in American Samoa. Department of

Agriculture, American Samoa Government.

Waterhouse, D.F. and K.R. Norris. 1987. Biological control: Pacific prospects. Inkata Press Pty Ltd.

Melbourne, Australia.

11

Cook Islands

Mr. Poona Samuel

Chief Quarantine Officer

Ministry of Agriculture

P.O. Box 96, Rarotonga, Cook Islands

Tel: 682 28711, Fax: 682 21881

E-mail:

and

Ms. Tania Temata

Senior Environment Officer

Environment Service

Government of the Cook Islands

P.O. Box 371, Rarotonga, Cook Islands

Tel: 682-21256, Fax: 682-22256

E-mail:

1. Main invasive alien species in the Cook Islands

Invasive alien species (IAS) include giant mimosa (Mimosa invisa), coconut flat moth (Agonoxena

pyrogramma), Queensland fruit fly (Bactrocera tryoni), and orchid weevil (Orchidophilus aterrimus).

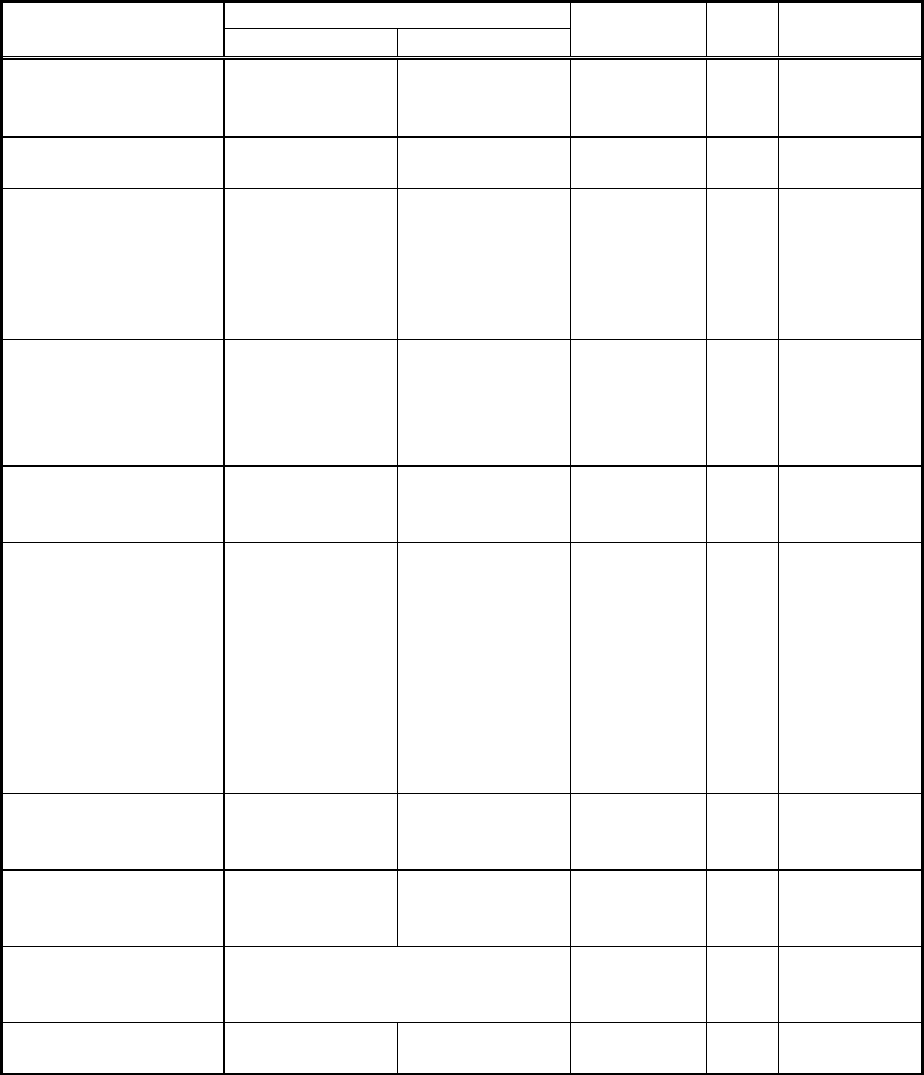

2. Summary of existing strategy and programs on IAS

The Ministry of Agriculture is currently implementing the following programmes to manage or

eradicate incursions of the following pests:

Pest/IAS

Method

giant mimosa

(Mimosa invisa)

This serious plant invasive was introduced in the 1960s. Biological

control is being used to control the plant.

coconut flat moth

(Agonoxena pyrogramma)

Biological control is being used, as well as internal quarantine to prevent

introduction to other islands

Lantana (Lantana camara)

Biological control agents are being introduced to the other islands.

Queensland fruit fly

(Bactrocera tryoni)

The first incursion occurred in the capital, Rarotonga, in late 2001.

Emergency procedures were initiated to eradicate the incursion with

male trapping, spot spraying of food lures and host destruction in the

incursion zone. The shipment of fruits and vegetables to other islands in

the country was prohibited without a quarantine certificate.

The Ministry of Agriculture has a fruit fly surveillance programme to

detect fruit fly incursions, using male attractants, cue lure and methyl

eugenol. No fruit flies have been trapped since February 2002.

orchid weevil

(Orchidophilus aterrimus)

Some plants have been destroyed on the infested property to try to

eradicate the pest.

12

The National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) for the Cook Islands identifies Invasive

Species Management as its second theme and sets two major goals: to reduce the adverse impacts of

IAS on indigenous species and ecosystems and to prevent new invasions. The NBSAP was completed

as part of the national assessment for the World Summit on Sustainable Development process and is

now being widely promoted within government agencies (see 3 and 4 below on legislative aspects).

3. Government departments/agencies concerned with IAS

At the current time, only the Ministry of Agriculture has direct responsibilities for invasives/pests for

economic reasons under the Plants Act 1973 and Animals Act 1975. The Ministry of Health has

responsibility for preventing the introduction of mosquitoes and human diseases.

However, the following government agencies could also contribute to the prevention and control of

invasives/pests:

⇒

Environment Service;

⇒

Cook Islands Natural Heritage Project; and

⇒

Island Governments of Aitutaki, Atiu, Mauke, Mangaia, Mitiaro, Palmerston, Pukapuka, Penrhyn,

Rakahanga and Manihiki.

4. Priorities identified for future work

4.1 Agriculture and internal quarantine

In 1998, the Ministry of Agriculture’s functions in all outer islands were devolved to the local

governments of those islands. Some of those island governments did not consider agriculture and

internal quarantine important and did not provide enough resources for those activities. During the

financial year 2002-2003, the Government of the Cook Islands reversed the 1998 decision. The

Ministry of Agriculture is now allocating resources for those activities, although funding is limited.

The introduction of the coconut flat moth (Agonoxena pyrogramma) in 1999/2000 caused serious

concern in the community because of the visible damage on coconuts and the negative impact this

might have on the tourism industry. The Ministry of Agriculture, with the assistance of the Secretariat

of the Pacific Community, has introduced biological control agents to control this pest in Rarotonga,

Atiu, and Aitutaki.

4.2 Greater coverage and awareness outside the agricultural sector

Initiatives for control, management, and eradication of IAS are much more developed for pests that

affect the agriculture development sector. More effort is required to study and manage the impact of

invasive species on the natural and native biodiversity of the Cook Islands. Following the completion of

the study by Space and Flynn (see 6 below), priority should be given to mapping the distribution of

IAS, particularly for the island of Rarotonga. Also important is the need to raise awareness of IAS and

the likely pathways for their incursions. Pictorial and/or photographic materials need to be obtained for

the awareness campaign. Very little is known about marine IAS.

13

4.3 Legislation

The Ministry of Agriculture is currently reviewing the Plants Act 1974 and Animals Act 1975.

Recommendations by a consultant funded by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the

United Nations included the abolition of some provisions of these laws, which currently prohibit the

introduction of certain plants and animals that are known IAS or pests. One of the co-authors of this

report does not agree with the consultant.

The Environment Service administers the Rarotonga Environment Act 1994-95 which only applies to

the island of Rarotonga. A National Environment Bill is due to be adopted before the end of 2003. The

Bill’s objective is to manage the environment of the Cook Islands in a sustainable manner: it contains a

provision to manage and control the introduction of IAS, including the requirement for an environment

impact assessment (IAS) for any activity that might have an adverse impact on the environment.

5. List of experts working in the field of biological invasions

⇒

Ministry of Agriculture

Government of the Cook Islands

P.O. Box 96, Rarotonga

Cook Islands

Dr. Maja Poeschko, Entomologist

Mr. William Wigmore, Director of Research

Mr. Ngatoko Ngatoko, Chief Quarantine Officer

⇒

Cook Islands Natural Heritage Project

Mr. Gerald McComack, Director

⇒

Ministry of Health

Ms Ngapoko Short, Director of Public Health

Mr. Tuaine Teokotai, Chief Public Health Inspector

⇒

Environment Service

Government of the Cook Islands

P.O. Box 371, Rarotonga

Cook Islands

Joseph Brider, Compliance and Biodiversity Officer

14

6. Bibliographic references

Extracted from Cook Islands Pest Lists Database, Plant Protection Service, Secretariat of the

Pacific Community

Allwood, A. 1999. List of fruit fly hosts in the Cook Islands. Compiled data based on the following

reports (a1-a8), Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) Suva, Fiji.

Allwood, A.J. and L. Leblanc. 1997. Losses caused by fruit flies Tephritidae) in seven Pacific Island

countries and territories (Diptera: pp. 208-211 in: Allwood, A.J. and R.A.I. Drew. Management

of Fruit Flies in the Pacific. ACIAR Proceedings No 76. 267 pp.

Anon. 1961. Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis (Bouche). CAB International Institute of Entomology.

Distribution maps of pests. Series A. Map 135.

Anon. 1971. Rhabdoscelus obscurus, CAB International Institute of Entomology. Distribution maps of

pests. Series A. Map 280.

Anon. 1981. Hellula undalIslands, CAB International Institute of Entomology. Distribution maps of

pests. Series A. Map 427.

Anon. 1993. Cosmopolites sordidus, CAB International Institute of Entomology. Distribution maps of

pests. Series A. Map 41.

Anon. 1940. reference title: Fourteenth Annual Report of the Department of Scientific and Industrial

Research, New Zealand. 100 pp.

Baker, R. 1988. List of interceptions from Cook Island bananas for the period 1986-1988., MAFQual,

Auckland, in Hill Gary. Visit to Aitutaki on 7th to 8th September, DSIR Plant Protection,

Auckland, New Zealand. 7 pp.

Bove, J.M. and R.Vogel (eds.). 1981. Description and illustration of virus and virus-like diseases of

citrus: a collection of color slides. Second edition International Organization of Citrus

Virologists (IOCV) and Institut de Recherches sur les Fruits et Agrumes (IRFA).

Butcher, C.F. 1981. Green vegetable bug advisory leaflet, South Pacific Commission No. 13, 4 pp.; 6

fig., (2 col.).

Charles, J. G. 1990. Visit to Rarotonga and Mauke, Cook Islands, 29 September to 11 October 1990.

Overseas travel report, DSIR Plant Protection, Auckland, New Zealand. 17 pp.

Cunningham, G.H. 1958. Hydnaceae of New Zealand. Part I - The Pileate genera Beenakia, Dentinum,

Hericium, Hydnum, Phellodon and Steccherinum., Transactions of the Royal Society of New

Zealand 85: 65-103.

Cunningham, G.H. 1963. The Thelephoraceae of Australia and New Zealand. New Zealand

Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, Bulletin No. 145. 359 pp.

Cunningham, G.H. 1965. Polyporaceae of New Zealand. New Zealand Department of Scientific and

Industrial Research, Bulletin 164. 304 pp.

15

De Barro, P. 1998. Survey of Bemisia tabaci Biotype B whitefly (also known as B. argentifolii) and its

natural enemies in the South Pacific. Final Report of ACIAR, Project No. 96/148 Sept. 1997.

Presented at the Second Meeting of the Pacific Plant Protection Organisation, Nadi, Fiji, 2-5

March.

Dingley, J.M., Fullerton, R.A., McKenzie E.H.C. 1981. Records of fungi, bacteria, algae, and

angiosperms pathogenic on plants in Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Niue, Tonga, Tuvalu, and

Western Samoa. 485 pp.; 1 map; 8 pp. of ref.

Drew, R.A.I. 1989. The Tropical Fruit Flies (Diptera: Tephritidae: Dacinae) of the Australasian and

Oceanian regions. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 26: 1-521.

Dumbleton, L.J. 1954. A list of plant diseases recorded in South Pacific Territories., South Pacific

Commission, Technical Paper No. 78. 78 pp.

Ellis, M.B. 1968. Dematiaceous Hyphomycetes. IX. Spiropes and Pleurophragmium., Mycological

Papers 114. 44 pp.

Grandison, G.S. 1990. Report on a survey of plant parasitic nematodes in the Cook Islands Southern

Group. South Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia. 9 pp.

Hill, G. 1990. Interim- & final report on a visit to Mauke, 16 to 17th March 1990 DSIR Plant

Protection, Auckland, New Zealand. 6 pp.

Hughes, S.J. 1993. Meliolina and its excluded species. Mycological Papers No. 166, 255 pp.; 6 pp. of

ref.

Johnston, A. 1965. Host list of fungi etc. and insects recorded in the South East Asia and Pacific

Region. Plant Protection Committee for the South East Asia and Pacific Region, Cocos nucifera

L. - coconut.

Johnston, A. 1965. New records of pests and diseases in the region. FAO Plant Protection Committee

Asia for the South East and Pacific Region.

Joseph, P.T. and M. Purea. 1973. Common pests and diseases of the Cook Islands. Cook Islands

Department of Agriculture. 3 pp. (mimeographed).

Kakishima, M., Kobayashi, T., and E.H.C. McKenzie.1995. A warning against the invasion of Japan by

the rust fungus, Coleosporium plumeriae, on Plumeria. Forest Pests 44(8): 144-147.

Karling, J.S. 1968. Zoosporic fungi of Oceania. I.Hyphochytriaceae. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell

Scientific Society 84: 166-178.

Karling, J.S. 1968. Zosporic fungi of Oceania. V. Cladochytridiaceae, Catenariaceae and

Blastocladiaceae. Nova Hedwigia 15: 191-201.

Karling, J.S. 1968. Zoosporic fungi of Oceania. III. Monocentric Chytrids. Mycopathologia et

Mycologia Applicata 36: 165-178.

Kassim, A.1993. Regional Fruit Fly Project [Cook Islands]. Sixth / Final Progress Report. 1st July 1992

- 30th November 1993. FAO/AIDAB/UNDP/SPC Regional Fruit Fly Project. 27 pp.

16

Kassim, A. 2001. Fruit fly in Cook Islands (Revised SPC Edition) Pest Advisory Leaflet No. 35.

Kassim, A. and A. Allwood. 1994. Fruit flies and their control in the Cook Islands. Leaflet, South

Pacific Commission, Fiji, Suva, ISBN 983-203-363-X. 8 pp.

LandCare Ltd. 1997. New Zealand Arthropod Collection. Mount Albert Research Centre, Auckland,

New Zealand.

Macfarlane, R., and G.V.H. Jackson.1989. Sweet Potato Weevil. Pest Advisory Leaflet No. 22. South

Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia.

Maddison, P.A. 1976. Records of Lepidoptera from the Cook Islands. UNDP/FAO Pest and Disease

Survey, Technical Document 11. 45 pp.

Maddison, P.A. 1993. Pests and other fauna associated with plants, with botanical accounts of plants.

UNDP/FAO-SPEC Survey of Agricultural Pests and Diseases in the South Pacific. Technical

Report Vol. 3. Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd. (Microfiches).

Madison, P. 1979. Pests in the Cook Islands: A report based on the work of the UNDP/FAO-SPEC pest

and disease survey in the South Pacific, 59 pp.

Martin, P. 1968. Studies in the Xylariaceae: IV. Hypoxylon, sections Papillata and Annulata. Journal of

South African Botany 34: 303-330.

Martin, P. 1969. Studies in the Xylariaceae: V. Euphypoxylon. Journal of South African Botany 35:

149-206.

Martin, P. 1970. Studies in the Xylariaceae: VIII. Xylaria and its allies. Journal of South African

Botany 36: 73-138.

Martin, N.A. 1995. Consultancy on whitefly control in the Cook Islands. A report prepared for the New

Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Hort Research Client Report No. 95/67. 30 pp.

Mataio, N. 1996. Short-term consultancy on crop loss estimates in Rarotonga, Aitutaki, Mangaia, Atiu

and Mauke due to incidence of silverleaf whitefly. A study funded by the SPC-German

Biological Control Project, South Pacific Commission, Suva, Fiji.

Meyer, J.Y. and G. Sherley. 2000. Preliminary review of the invasive plants in the Pacific Islands.

Pages 85-114 in Invasive species in the Pacific; a technical review and draft regional strategy

SPREP. Apia. 190 pp.

Miller, J.H. 1961. A monograph of the world species of Hypoxylon. University of Georgia Press,

Athens. 158 pp.

Mossop, D.W. and P.R. Fry. 1984. Records of viruses pathogenic on plants in Cook Islands, Fiji,

Kiribati, Niue, Tonga and Western Samoa Survey of Agricultural Pests and Diseases, Technical

Report Vol 7, UNDP and FAO.

Mound, L.A. and A.K. Walker. 1987. Thysanoptera as tropical tramps: New Entomologist, 9. New

Zealand. Records from New Zealand and the Pacific. pp. 70-85.

17

Neill, J.C. 1944. Rhizophogus in citrus. New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology A25: 191-

201.

Pearson, M.N., G.V.H. Jackson, S.P. Pone, R.L.J. Howitt. 1993. Vanilla viruses in the South Pacific.

Plant Pathology 42:127-131.

Poeschko, M. 1997. Observations during her work within the Ministry of Agriculture in the Cook

Islands. Volunteer of the German Development Service (GDS) stationed in Port Moresby,

Papua New Guinea.

Purea, M., R. Putoa, and E. Munro. 1997. Fauna of fruit flies in Cook Islands and French Polynesia.

Pages 54-56 in Allwood, A.J. and R.A.I. Drew. Management of fruit flies in the Pacific. ACIAR

Proceedings No 76. 267 pp.

Reddy, D.B. 1971. New records of pests and diseases in the South East Asia and Pacific Region. FAO

Plant Protection Committee for the South East Asia and Pacific Region, Technical Document

no. 83. 7 pp.

Smith, I.M., D.G. McNamara, P.R. Scott, M. Holderness. 1997. Quarantine pests for Europe. Second

edition. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

Stockdale, P.M. 1956. Nannizzia gypsea. CMI Descriptions of Pathogenic Fungi and Bacteria No. 68.

Stout, O.O. 1982. Plant quarantine guidelines within the Pacific Region.UNDP/FAO-SPEC Survey

Agricultural Pests and Diseases in the South Pacific, viii + 656 pp.

Swarbrick, J.T. 1997. Weeds of the Pacific Islands. South Pacific Commission. Technical Report No.

209. 124 pp.

Sykes, W.R. 1980. Sandalwood in the Cook Islands. Pacific Science 34: 77-82.

Walker, A.K. and L.L. Deitz. 1977. A survey of parasitic and predatory insects in the Cook Islands,

with historical review. 42 pp.

Walker, A.K. and L.L. Deitz,. 1979 A review of entomophagous insects in the Cook Islands. New

Zealand Entomologist. Vol. 7, No. 1. 13 pp.

Waterhouse, D.F. 1993. Biological control, Pacific prospects- Supplement 2. Australian Centre for

International Agricultural Research, Canberra, Australia. 138 pp.

Waterhouse, D.F. and K.R. Norris. 1987. Biological control, Pacific prospects. Australian Centre for

International Agricultural Research, Melbourne, Australia. 454 pp.

Waterhouse, D.F. and K.R. Norris. 1989. Biological control, Pacific prospects- Supplement 1

Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, Canberra, Australia. 123 pp.

Wearing, C.H. 1981. Report on visit to Cook Islands 3-10 April 1981. Entomology Division, DSIR,

Auckland New Zealand. 15 pp.

Wilder G.P. 1931. Flora of Rarotonga. Bulletin, Bernice P. Bishop Museum 86. 113 pp.

18

Williams D.J., and G.W. Watson. 1988. The scale insects of the tropical South Pacific Region. Part 1.

The armoured scales (Diaspididae). CAB International, Wallingford. 290 pp.

.

Williams D.J. and G.W. Watson. 1990. The scale insects of the tropical South Pacific Region. Part 3.

The soft scales (Coccidae) and other families. CAB International, Wallingford. 267 pp.

Williams D.J. and G.W. Watson. 1988. The scale insects of the tropical South Pacific Region. Part 2.

The mealy bugs (Pseudococcidae). (Wallingford: CAB International.). 248 pp.; 9 pp. of ref.

Willson, B.W. 1994. SPC-German Biological Control Project, Report on Trip to the Cook Islands, 8-16

September 1994. Alan Fletcher Research Station, Queensland of Land, Australia. 13 pp.

Extracted from Space J.C. and Flynn T.: Report to the Government of the Cook Islands on

Invasive Plant Species of Environmental Concern

Binggeli, P. 1996. A taxonomic, biogeographical and ecological overview of invasive woody plants.

Jour. Veg. Sci. 7:121-124.

Cronk, Q.C.B. and J.L.Fuller. 1995. Plant invaders. Chapman and Hall. 241 pp.

Csurhes, S. and R. Edwards. 1998. Potential environmental weeds in Australia: Candidate species for

preventative control. Canberra, Australia. Biodiversity Group, Environment Australia. 208 pp.

D’Antonio, C.M. and P.M.Vitousek. 1992. Biological invasions by exotic grasses, the grass-fire cycle,

and global change. Ann. Rev. Ecol. and System. 23: 63-87.

Drake, J., F.di Castri, R. Groves, F. Kruger, H. Mooney, R. Rejmanek, and M. Williamson. (eds.) 1989.

Biological invasions: a global perspective. John Wiley & Sons, NY. 525 pp.

Hafliger, E. and H. Scholz. 1980. Grass weeds. CIBA-GEIBY Ltd., Basle, Switzerland. Two volumes.

Hafliger, E. 1980. Monocot weeds. CIBA-GEIBY Ltd., Basle, Switzerland. 132 pp. plus plates.

Harley, K.L.S. and I.W. Forno. 1992. Biological control of weeds: a handbook for practitioners and

students. Inkata Press, Melbourne/Sydney. 74 pp.

Holm, L.G., D.L.Plucknett, J.V.Pancho, and J.P.Herberger. 1977. The world’s worst weeds: distribution

and ecology. East-West Center/University Press of Hawai‘i. 609 pp.

Hughes, Colin E. 1994. Risks of species introductions in tropical forestry. Commonwealth Forestry

Review 73:243-252.

Julien, M.H. (ed.). 1992. Biological control of weeds: a world catalogue of agents and their target

weeds (third edition). CAB International, Wallingford, UK. pp. 89-108, 138-141.

Large, M.F. and Q.C.B. Cronk. 1996. Ardisia: the next pest? Aliens 4:4.

MacArthur, R.H. and E.O.Wilson. 1967. The theory of island biogeography. Princeton, New Jersey:

Princeton Univ. Press. 203 pp.

19

Merlin, M.D. 1985. Woody vegetation in the upland region of Rarotonga, Cook Islands. Pac. Sci.

39:81-99.

Merlin, M.D. 1991. Woody vegetation on the raised coral limestone of Mangaia, southern Cook Islands.

Pac. Sci. 45:131-151.

Meyer, J-Y. 1998. Mécanismes et gestion des invasions biologiques par des plantes introduites dans des

forêts naturales à Hawai‘i et Polynésie Française: une étude de cas [Mechanisms and

management of biological invasions by alien plants in Hawaiian and French Polynesian natural

forests: a case study]. Dèlégation à la Recherche, B.P. 20981 Papeete, Tahiti, Polynésie

Française.

Meyer, J-Y. 2000. Preliminary review of the invasive plants in the Pacific islands (SPREP Member

Countries) in: Sherley, G. (tech. ed.). Invasive species in the Pacific: a technical review and

draft regional strategy. South Pacific Regional Environment Programme, Samoa. 190 pp.

Meyer, J-Y. and J.Florence. 1996. Tahiti’s native flora endangered by the invasion of Miconia

calvescens DC. (Melastomataceae). Journal of Biogeography 23:775-781.

Mueller-Dombois, D., and F.R. Fosberg. 1998. Vegetation of the tropical Pacific Islands. New York,

Springer-Verlag. 733 pp.

Muniappan, R. 1989. Operational and scientific notes: biological control of Lantana camara L. in Yap.

Proc. Haw. Ent. Soc. 29:195-196.

Muniappan, R., G.R.W. Denton, J.W. Brown, T.s. Lali, U. Prasad, and P. Sing. 1996. Effectiveness of

the natural enemeis of Lantana camara on Guam: a site and seasonal evaluation. Entomophaga

41: 167-182.

Muniappan, R. and C.A.Viraktamath. 1986. Status of biological control of the weed, Lantana camara in

India. Trop. Pest Management 32:40-42.

Parsons, W.T. and E.G. Cuthbertson. 1992. Noxious weeds of Australia. Inkata Press,

Melbourne/Sydney. 692 pp.

Smith, A.C. 1979-1991. Flora Vitiensis nova: a new flora of Fiji. Lawai, Kauai, Hawai‘i. National

Tropical Botanical Garden. Six Volumes.

Staples, G.W., D.Herbst, and C.T. Imada. 2000. Survey of invasive or potentially invasive cultivated

plants in Hawai‘i. Bishop Museum Occasional Papers No. 65. 35 pp.

Stone, B.C. 1970. The flora of Guam. Micronesica 6:1-659.

Swarbrick, J.T. 1997. Weeds of the Pacific Islands. Technical paper No. 209. South Pacific

Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia. 124 pp.

Thaman, R.R. 1999. Wedelia trilobata: daisy invader of the Pacific Islands. Preliminary draft discussion

paper prepared for the SPREP Regional Invasive Species Strategy for the South Pacific Islands

Region, Nadi, Fiji, 26 September-1 October, 1999.

20

Tolfts, A. 1997. Cordia alliodora: the best laid plans. Aliens 6 (1997): 12-13.

Wagner, W.L., D.R. Herbst, and S.H. Sohmer. 1999. Manual of the flowering plants of Hawai‘i, revised

edition with supplement by Wagner, W.L. and D.R. Herbst, pp. 1855-1918. University of

Hawai‘i Press, 1919 pp. in 2 volumes.

Waterhouse, D.F. 1993. Biological control: Pacific prospects. Supplement 2. Australian Centre for

International Agricultural Research, Canberra. 138 pp.

Waterhouse, D.F. 1994. Biological control of weeds: Southeast Asian prospects. Australian Centre for

International Agricultural Research, Canberra. 302 pp.

Waterhouse, D.F. 1997. The major invertebrate pests and weeds of agriculture and plantation forestry

in the Southern and Western Pacific. The Australian Centre for International Agricultural

Research, Canberra. 69 pp.

Waterhouse, D.F. and K.R. Norris. 1987. Biological control: Pacific prospects. Inkata Press,

Melbourne. 454 pp.

Welsh, S. L. 1998. Flora societensis: a summary revision of the flowering plants of the Society Islands.

E.P.S. Inc., Orem, Utah. 420 pp.

Whistler, W.A. 1983b. Weed handbook of Western Polynesia. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische

Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH, Eschborn. 151 pp.

Whistler, W.A. 1988. Checklist of the weed flora of western Polynesia. Technical Paper No. 194, South

Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia. 69 pp.

Whistler, W.A. 1990. Ethnobotany of the Cook Islands: The plants, their Maori names, and their uses.

Allertonia 5(4):347-424.

Whistler, W.A. 1992a. Flowers of the Pacific Island seashore. Isle Botanica, Honolulu. 154 pp.

Whistler, W.A. 1992b. Vegetation of Samoa and Tonga. Pac. Sci. 46(2):159-178.

Whistler, W.A. 1995. Wayside plants of the islands. Isle Botanica, Honolulu. 202 pp.

Williamson, M. 1996. Biological invasions. Chapman and Hall. 244 pp.

21

Fiji

Fiji was not represented at the GISP Austral-Pacific Workshop, as its delegate, Mr Aisea Waqa, Fijian

National Focal Point for the International Plant Protection Convention, sadly passed away while

travelling to the meeting.

His institutional details were:

Mr Aisea Waqa

Principal Agricultural Officer, Quarantine Section

Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forests

Private Mail Bag

Post Office Raiwaqa

Tel: 679-312-512

Fax: 679-305-043

Email: [email protected]

The editors and workshop participants record their sincere condolences to the Government of Fiji and to

Mr Waqa's family and colleagues.

22

French Polynesia

Dr. Jean-Yves Meyer

Délégation à la Recherche

Ministère de la Culture, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche

Gouvernement de Polynésie française

B.P. 20981 Papeete, Tahiti

French Polynesia

Phone: (689) 501 555

Fax: (689) 43 34 00

E-mail : [email protected]

Introduction

⇒

Characteristics of the islands of French Polynesia

French Polynesia is a French overseas territory located in the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of 121

tropical oceanic islands and islets divided into five archipelagoes, namely the Austral, the Gambier, the

Marquesas, the Society, and the Tuamotu Islands. These islands are scattered between 7° and 27°

South, and 134° and 152° West over 5,030,000 km

2

of ocean (Exclusive Economic Zone). The best-

known island, Tahiti, is the largest (1045 km

2

) and the highest (2241m elevation).

The islands of French Polynesia are characterised by:

−

significant geographic isolation (Tahiti is 6000 km from Australia, and the USA and 8000 km from

Chile);

−

a relatively young geological age (between 0.2 to 28.6 million years old);

−

a small land area (a total of 3,520 km

2

) with only 8 islands larger than 100 km

2

; and

−

a great diversity of habitat types (young high volcanic islands and rocky islets, old barrier-reef

islands, coral limestone islands or atolls and coral islets, and raised limestone islands or “makatea”).

With an endemism rate of 75% for flowering plants, French Polynesia has one of the most unique

native flora in the Pacific Ocean after the Hawaiian Islands (90%) and New Caledonia (85%). It has

also one of the highest number of sea-birds (27 species) in tropical regions, and some of the most

endangered land birds worldwide (e.g. the Nuku Hiva pigeon, Ducula galeata, with 100-150 birds left

and the Tahiti monarch or flycatcher, Pomarea nigra, with less than 50 birds).

⇒

Human settlement and alien species introductions

The first inhabitants of French Polynesia were Polynesian migrants who sailed from Western Polynesia

(Samoa, Tonga) on their double-outrigger canoes about 2700 years ago, settling in the different

archipelagoes between 700 BC and 700 AD. About 80 plant species are considered to be Polynesian or

“aboriginal” introductions, including several food plants, including taro (Colocasia esculenta

(Araceae)), fe’i or wild banana (Musa troglodytarum (Musaceae)), breadfruit tree (Artocarpus edulis

(Moraceae)), Malay apple (Syzygium malaccense (Myrtaceae)), ritual or medicinal plants such as ti

plant (Cordyline fruticosa (Agavaceae)), kava (Piper methysticum (Piperaceae)), tiare tahiti (Gardenia

tahitensis (Rubiaceae)), and about 50 adventives or casual weeds accidentally introduced as seed

contaminants.

23

Among these introduced plants, 24 are currently naturalized. The latter include the Tahitian chestnut

(Inocarpus fagifer (Fabaceae)), a large buttressed tree that forms monospecific stands in the low and

wet valleys, and the candle nut (Aleurites moluccana (Euphorbiaceae)), a tree widely naturalized on

low-elevation slopes and mid-elevation plateaus up to 500 m.

The first Polynesians brought animals such as domestic chickens (Gallus gallus), pigs (Sus scrofa),

dogs (Canis familiaris), and Polynesian rats (Rattus exulans), either unintentionally or intentionally as a

food source. Rattus exulans is now found in nearly all the islands of French Polynesia. It coexists with

endemic land birds, but has been documented to impact sea-bird colonies on small islets in French

Polynesia. The effects of all these introduced or alien plant and animal species on the native biota were

probably minor compared to the land clearing, burning, planting and irrigating, as practised by early

Polynesian settlers.

The first European explorers landed in 1595 in the Marquesas Islands (Spanish captain Mendaña), 1606

in the Tuamotu Islands (Spanish captain Quirõs), and between 1767-69 in the Society Islands (English

captains Wallis and Cook, French captain Bougainville). Since then, recent or “modern” introductions

of alien species include more than 1500 plants (about 520 of them are currently naturalized), the

carnivorous black or ship rat (Rattus rattus) and the brown or Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus),

herbivorous ungulates (goat, sheep, cattle, horse), predatory cats, birds, fishes and invertebrates,

including mollusks, and detrimental insects such as the mosquito (Aedes aegypti) which is a dengue

fever vector. Feral ungulate populations rapidly began to open, degrade, and destroy upslope forests,

especially in the Marquesas and Austral Islands.

Today, 76 of the 121 islands of French Polynesia are inhabited. The population is estimated to be about

240,000 in 2002, four times higher than the population 50 years ago (ca. 62,000 in 1950). Seventy-five

percent of the population is restricted to the islands of Tahiti and Moorea in the Society archipelago.

1. History of harmful introductions and biological invasions in French Polynesia

The following chronology reviews the harmful or noxious invasive alien plant and animal species

which have caused or currently cause significant ecological impacts and/or economical damage, or

adverse health effects in French Polynesia. All these species were introduced unintentionally or

intentionally by human activities. This overview is based on various bibliographical sources (scientific

papers and “grey” literature) and on personal communications or observations for species introductions

that have taken place during the last decade.

1767-69 Accidental introduction of black or ship rats (Rattus rattus) with the first European sailors.

Black rats are considered to have driven endemic land birds to extinction, especially the

lorikeets (Vini spp. (Psittacidae)), the monarchs or flycatchers (Pomarea spp.

(Muscicapidae)) and the ground doves (Gallicolumba spp. (Columbidae)).

1815 Intentional introduction of the common guava (Psidium guajava (Myrtaceae)) by Bicknell.

During his short visit to Tahiti in November 1835 on the Beagle, Charles Darwin noted that

“…the species is so abundant that it is quite a weed.”

1845 Intentional introduction by English marine surgeon Francis Johnston of the weedy legumes

Acacia farnesiana, Leucaena leucocephala and Mimosa pudica, as well as the yellow elder

(Tecoma stans (Bignoniaceae)) and the Chinese or strawberry guava (Psidium cattleianum

(Myrtaceae)). They belong to the most aggressive plant invaders in native forests of French

Polynesia. Tecoma stans, which was reported by botanist F. R. Fosberg only in a few valleys

in 1934, had invaded nearly all the mesic zone of Tahiti by 1954.

24

1853 Intentional introduction of the weedy Lantana (Lantana camara (Verbenaceae)) to Tahiti by

French Marine Captain Chappe, as an ornamental plant.

1885 The swamp harrier (Circus approximans (Accipitridae)) was purposely introduced and

released on Tahiti by the German Consul for rat control. This predatory bird colonized all the

Society Islands and is commonly found at high elevation (up to 1,500 m) on Tahiti. It is

thought to have seriously affected native birds, such as the white tern (Gygis alba

(Sternidae)), the endemic gray-green fruit dove (Ptilinopus purpuratus (Columbidae)), the

Tahiti reed warbler (Acrocephalus caffer (Muscicapidae)). The swamp harrier is one of the

main causes for the extinction of the Polynesian imperial pigeon (Ducula pacifica aurorae

(Columbidae)) and the blue lorikeet (Vini peruviana (Psittacidae)) in Tahiti.

1887 French Marine Pharmacist J.-F. Raoul introduced about 210 plant species in the town of

Papeete (Tahiti) in a place that later became known as the “Jardin Raoul.”

1889 First detection of the scale insect (Aspidiotus destructor (Homoptera, Diaspididae)) that

attacks and kills coconut trees and other palm species.

1906-10 Accidental introduction of the white sand-fly (Stylocenops albiventris (Ceratopogonidae)) in

the Marquesas Islands, locally called the “Prussian nono” because it was brought by German

boats coming from New Guinea. The “nonos” which bite both humans and animals are now a

nuisance to tourism development in the Marquesas.

1906-08 Intentional introduction of the common myna (Acridotheres tristis (Sturnidae)) to control

introduced wasps on Tahiti. This aggressive bird is thought to predate the eggs and young of

the Tahiti swiftlet (Collocalia leucophaeus (Apodidae)) and may compete for food with the

Tahiti reed warbler (Acrocephalus caffer (Muscicapidae)). It was also introduced to Hiva Oa

(Marquesas Islands) in 1918 where it is thought to have displaced some endemic land birds

such as the Marquesan warbler (Acrocephalus caffer mendanae (Muscicapidae)), the

Marquesan swiftlet (Collocalia ocista (Apodidae)), and the white-capped fruit-dove

(Ptilinopus dupetitthouarsii (Columbidae)). Despite a law enacted in 1938 prohibiting alien

bird introductions, common mynas were intentionally released on two atolls of the Tuamotu

archipelago (Hao and Mururoa) in 1976, and in 2002 they were observed in the town of

Taihoae on the island of Nuku Hiva (Marquesas Islands) and on the raised atoll of Makatea

(Tuamotu Is.).

1924 Accidental introduction of the mosquito (Aedes aegypti (Culicidae)) in Tahiti, the main vector

insect of the dengue disease. It has spread to all the islands of French Polynesia, except on the

southeastern most inhabited island of Rapa (Austral Islands). Dengue is still one of the most

serious epidemic diseases in French Polynesia.

1925 First detection of the fruit fly (Bactrocera (Dacus) luteola (Diptera)) in Bora Bora (Society

Islands) by Entomologist L. E. Cheesman.

1926 About 200 mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis (Poeciliidae)) were introduced to Tahiti for

mosquito control, as well as 50 common carp (Cyprinus carpio), 30 large-mouth bass

(Micropterus salmoides), 12 channel catfish (Ictaturus punctatus) and 34 frogs. Mosquito fish

is responsible for disrupting aquatic ecosystems and destroying native insect species, such as

damselflies.

25

1927 Intentional introduction of the great horned owl (Bubo virginianus (Strigidae)) to Hiva Oa

(Marquesas Islands), where they have become well established up to 1000 m elevation. A

total of eight birds from San Francisco was released by the Lord Bishop Le Cadre for rat

control. They are thought to have affected all the native bird species on Hiva Oa, especially

the Marquesan kingfisher (Todiramphus godeffroyi (Alcedinidae)) and have contributed to

the extinction of the red-moustached fruit dove (Ptilinopus mercierii (Columbidae)).

1928 First mention of the fruit-fly (Bactrocera (Dacus) kirkii) in Tahiti, yet found in the Tuamotu,

Society, Gambier and Austral Islands (except on Rapa), but not yet in the Marquesas yet. This

species is known to attack fruits of 45 host-plant species belonging to 23 different plant

families.

1932 Entomologist W. M. Wheeler documented the invasion of the tropicopolitan big-headed ant

(Pheidole megacephala) in the Marquesas Islands, up to 1000 m elevation. In 1939, A.M.

Adamson considered it the most destructive of all foreign enemies to the native entomofauna

in the Marquesas. The big-headed ant is implicated in the exclusion of native and endemic

spiders in Hawai'i.

1936 A "hacienda snake" (of unknown species) escaped the US ship "Director," and was captured

on the docks of Papeete harbour. Introduction of the large legume tree (Paraserianthes

falcataria (Fabaceae)), commonly planted as a shade tree for coffee plantations in the Society

and the Austral Islands, now widely naturalized.

1937 Introduction of Miconia (Miconia calvescens (Melastomataceae)) in a private botanical

garden (now called the Papeari or Harrison Smith Botanical Garden) as an ornamental plant

by Harrison Willard Smith. This retired U.S. professor of physics planted more than 250

imported plant species between 1921 and 1944, including the currently invasive African tulip

tree (Spathodea campanulata (Bignoniaceae)) in 1932, the trumpet tree (Cecropia peltata

(Cecropiaceae)) in 1926, the shoebutton ardisia (Ardisia elliptica (Myrsinaceae)) in 1939, the

Brazilian pepper (Schinus terebinthifolius (Anacardiaceae)) in 1927, the rose-myrtle

(Rhodomyrtus tomentosa (Myrtaceae)) in 1928, the coco plum (Chrysobalanus icaco

(Chrysobalanaceae)) in 1922, and the night-blooming jasmine (Cestrum nocturnum

(Verbenaceae)) in 1936. The first dense stands of the small tree M. calvescens were observed

in the early 1970’s on the Taravao plateau in Tahiti. Nature protection groups and French and

US scientists tried to raise awareness of local authorities to the potential threat, but met little

success at the time. On Tahiti, about 80,000 ha have been invaded by miconia, which is

sometimes called “the purple plague” or the “green cancer.” Miconia has also invaded about

3,500 ha on Moorea (35% of the island surface) and between 350-450 ha on Raiatea (2.5%)

in the Society Islands.

1948 First observation by entomologist P. Viette of the alien moth (Othreis fullonia (Noctuidae)).

In 1969, this moth was reported to severely attack citrus on the island of Moorea (Society

Islands) and eventually caused a local economic collapse.

1950 First report of the presence in Tahiti of the water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes

(Pontederiaceae)), introduced as an ornamental plant. This aquatic invasive plant spread in

the ponds near the Faaa International Airport in 1973, where it is being mechanically

removed.

26

1956 Introduction of the giant sensitive plant (Mimosa invisa), a prickly legume weed. Its pathway

of introduction may have been accidental as a seed contaminant or intentional as a fodder

plant.

1957 Introduction of the predatory fish tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) as a food source.

1959 First report of the swamp sand-fly (Culicoides belkini), locally called the white nono, on Bora

Bora. The fly was first detected in a small sandy islet or motu where the airstrip was built,

and was supposedly introduced by US airplanes coming from Fiji. It has since spread to all

the Society Islands and to the atolls of Rangiroa and Hao in the Tuamotu Archipelago around

1966 (the only atolls to have airstrips at that time).

1960 The coconut leaf hispa or coconut hispine beetle (Brontispa longissima (Chrysomelidae)) was

accidentally introduced with ornamental palms from New Caledonia. It attacks and eventually

kills palms and coconut trees. This beetle quickly spread to all the Society Islands, then in

1970 on Nuku Hiva (Marquesas Islands), in 1981 on Tubuai (Austral Islands), and in 1983 on

Rurutu (Austral Islands) and Rangiroa (Tuamotu Islands).

1967 Intentional introduction of the giant African snail (Achatina fulica (Achatinidae)) on Tahiti

and Moorea as a food source. It was introduced in the Marquesas Islands in 1973. This

herbivorous snail rapidly became an agriculture pest, with up to 1.5 tons of snails per day

collected on Tahiti.

1970 Accidental introduction of the Queensland fruit-fly (Bactrocera (Dacus) tryoni,) native to

Australia. It was probably introduced to Tahiti from New Caledonia (where it is present since

1969) with infected fruits and is now present in all the Society, Tuamotu, Gambier and

Austral Islands, except Rapa. This species attacks the fruits of 113 host-plant species.

1974 The Department of Agriculture of French Polynesia released the carnivorous or rosy-wolf

snail (Euglandina rosea (Spiraxidae)) in Tahiti by control the giant African snail. This

predator was also introduced to Moorea in 1977 where it caused the extinction of seven

endemic tree snail species of the family Partulidae (Partula spp.) only ten years after its

introduction. Endemic Partulids are still surviving in remote areas of Tahiti (Te Pari cliffs)

and in high-elevation cloud forests above 1000 m elevation where the carnivorous snail is not

present. All the Partulids of Bora Bora (two species) and Tahaa (six species) are now thought

to be extinct, as well as two species on Huahine (of the four known) and 29 species on

Raiatea (of the 33 known). The endemic tree snails of the Marquesas and the Austral Islands

where Euglandina rosea is present are under threat. The same year, accidental introduction of

the Chinese rose beetle (Lepadoretus (Adoretus) sinicus (Scarabaeidae)) from Hawai’i where

it feeds on more than 350 plants, including 50 cultivated species. In four years, this

defoliating insect spread 30 km from its first introduction site at the Faaa International

Airport.

1977 Fraudulent introduction of young citrus plants infected by the tristeza or CTV (Citrus Tristeza

Virus) transmitted by an introduced aphid insect (Toxoptera citrida). The virus attacks orange

and lemon trees.

1979 The red-vented bulbuls (Pycnonotus cafer (Pycnonotidae)) are first noticed in the residential

area of Papeete. This frugivorous bird is now common up to 1000 m elevation on Tahiti, and

has become a pest in agriculture, as well as an active disperser of invasive alien plants. It is

said to have negative interactions with the Tahiti monarch (Pomarea nigra).

27

1988 First observation in Tahiti of the thrips (Thrips palmi (Thripidae)) which infests a wide

variety of crops, especially vegetables.

1990s Observation in Tahiti of the spiralling whitefly (Aleurodiscus dispersus (Aleyrodidae)), a pest

of vegetables, fruit trees, ornamentals and shade trees which has spread rapidly through the

Pacific after gaining establishment in Hawai’i in 1978.

1994 Two non-identified iguanas escaped from a yacht, and disappeared on the atoll of Rangiroa in

the Tuamotu Islands.

1995-96 Accidental introduction of the common house gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus (Gekkonidae)),

now widespread in the urban areas of Tahiti.

1995-97 New sightings of Miconia calvescens in the islands of Tahaa (Society Islands), Nuku Hiva

and Fatu Hiva (Marquesas Islands), Rurutu and Rapa (Austral Islands). The plant pest was

accidentally introduced with contaminated soil on car wheels, bulldozers and tractors or in

gravel and soil piles imported from Tahiti.

1996 Accidental introduction of the Red Oriental fruit-fly (Bactrocera dorsalis) in Tahiti, first

sighted on the Taravao Plateau. It spread to Moorea (Society Islands) and to the atoll of Hao

(Tuamotu Islands) in 2000.

1997 Discovery of a young frog larva with ornamental fishes bought in a pet-store in Papeete. The

red-billed Leiothrix, also called Pekin or Japanese robin (Leiothrix lutea (Muscicapidae))

were sold in a pet store in Papeete. This colourful frugivorous species is known to have

spread in Hawai'i where it actively disperses invasive alien plants.

1998 Sudden invasion by a non-identified red stink bug (Heteroptera, Coreidae) on the raised

limestone island of Makatea (Tuamotu Islands) which attacks fruiting trees. The Pacific fruit-

fly (Bactocera xanthodes) was accidentally introduced to Raivavae (Austral Islands) from a

boat coming from other Pacific Islands. This species is known from Cook, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga

and Vanuatu. B. xanthodes was found on Rurutu in 2000 (Austral Islands), but has not yet

spread to other archipelagoes of French Polynesia.

1999 A non-identified squirrel that escaped from a Korean fishing boat was observed on the docks

of Papeete. A young green iguana (Iguana iguana) was found in the town of Papeete,

captured, and kept in captivity where it eventually died. The Queensland fruit-fly (Bactrocera

tryoni) was captured in the village of Taiohae in Nuku Hiva (Marquesas Islands, northern

group) and in the village of Vaitahu in Tahuata (Marquesas Islands, southern group).

2000 Discovery of unidentified piranhas with other ornamental fishes bought in a pet-store in the

town of Papeete. The two-spotted leafhopper (Sophonia rufofascia) was discovered by US

entomologists during a field-trip to Tahiti. The insect is known to cause dieback of cultivated

plants, as well as native plants, especially the common fern (Dicranopteris linearis

(Gleicheniaceae)).

2001 Sudden population explosion of the glassy-winged sharpshooter (Homalodiscus coagulata

(Cicadellidae)) in Tahiti. This insect was first reported by local entomologist R. Putoa of the

Department of Agriculture (Service du Développement Rural) in 1999 on a Lagerstroemia

ornamental tree (Lythraceae).

28

2002 Live giant cane toads (Bufo marinus, Bufonidae) were found in a container with wood logs

shipped from Fiji. The same year, live snail (Helix aspera) was found by the Plant Protection

Section of the Service du Développement Rural in a container from France with three live

plants. Green swordtail fishes (Xiphophorus helleri) were first noticed by aquatic biologist R.

Englund of the Bishop Museum of Honolulu in the Papenoo river in Tahiti. They are known

to bring in fish parasites like leeches and internal parasites and to heavily prey on young

stream native gobies in Hawai’i.

2003 Discovery of an escaped corn snake (Elaphe guttata (Colubridae)) above the dumping station

of the town of Faaa in Tahiti.

2. Development of a strategy to combat invasive species in French Polynesia

French Polynesia was declared a French protectorate in 1842, then a French colony in 1880. It was

included in the French Pacific Settlements (Etablissements Français de l’Océanie (E.F.O.)) in 1946

along with New Caledonia and Wallis & Futuna. It became a French Overseas Territory (Territoire

français d’Outre-Mer (T.O.M.) in 1957. The Statute of Self-Government, enacted in September 1984,

granted the Territory of French Polynesia complete responsibility for its environmental protection

policy, as well as for agriculture, reef and marine environments, and associated natural resources.

The following chronology reviews the legislative texts that have been enacted to control species

introductions in French Polynesia:

1936 Decree controlling the entrance of noxious insects and animals into the French Pacific

Settlements. The introduction of reptiles, insects, felines, and birds of prey is prohibited under

this decree and all incoming ships into harbours must declare any animals on board.

1938 Decree banning the introduction, possession, and release of any introduced birds in the

French Pacific Settlements.

1971 Law N°71-195 prohibiting the introduction, transportation, and rearing of the giant African

snail Achatina fulica. Chemical treatment of soil from infected islands to Achatina-free

islands is obligatory.

1972 Law N°77-772 declaring the environment (including nature protection) to be within the

jurisdiction of the Territory of French Polynesia.

1977 Law N°77-93 prohibiting the import of all live animals into French Polynesia, except for

exemptions approved by the Government Council.

1984 Law N°84-260 nominating a Minister of Environment and establishing the Department of

Environment (Délégation à l’Environnement) in charge of nature protection.

Decree N°985CM, voted by the Government of French Polynesia, prohibiting new

importations of alien birds of the families Accipitridae (hawks and eagles), Falconidae

(falcons), Strigidae (barn-owls) and Tytonidae (owls), as well as Columbidae (doves and

pigeons) and Rallidae (rails).

29

1988 Formation of a collaborative Miconia Research and Control Program, following the

recognition by the French Polynesian and French authorities of the severe ecological impacts

caused by the invasive alien tree Miconia (Miconia calvescens). It was led by the French

Overseas Research Organization (Office de Recherche Scientifique et Technique d'Outre-Mer

(ORSTOM), now renamed Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD)). The aims of

the project were to conduct studies on the bio-ecology and distribution on miconia, and to

find efficient control method for this invasive plant. Funds were provided by both the French

Polynesian Ministry of the Environment and France.

1990 Decree N°90CM voted by the Government of French Polynesia, declaring Miconia

calvescens a noxious plant in French Polynesia. Cultivation and transportation within and

between islands is prohibited.

1991-92 The first manual and chemical control operations against Miconia were launched on the

island of Raiatea, sponsored and funded by the Délégation à l’Environnement with the

logistic support of the Service du Développement Rural and the voluntary participation of

many local schoolchildren and their teachers.

1993 First intervention of 100 French Army soldiers (mostly French Polynesians doing their

compulsory military service) to remove Miconia on Raiatea for one week, with the logistic

support of the Service du Développement Rural and the participation of local schoolchildren.

This Miconia intervention was repeated annually during the period 1997-2002.

1995 Law N°95-257AT on Nature Protection (Délibération sur la Protection de la Nature),

prepared by the Ministry of Environment and voted by the Territorial Assembly of French

Polynesia. Its objectives are to protect endangered endemic species, and natural areas with

strong conservation value, and to identify and control alien species which are considered a

threat to the biodiversity of French Polynesia.

1996 Law N°96-42AT on Plant Protection prepared by the Ministry of Agriculture and voted by

the Territorial Assembly of French Polynesia. One of its aims is to prevent the introduction of

noxious organisms (plant pathogens, alien insects, invertebrates and plants) that could

become agricultural or environmental pests in French Polynesia.

1997 A collaborative agreement was signed between the French Polynesian Government and the

Hawai’i Department of Agriculture for a Miconia Biological Control Program. The same

year, the First Regional Conference on Miconia Control was held in Papeete (Tahiti),

sponsored and funded by the Department for Research (Délégation à la Recherche) and by

ORSTOM.

1998 Decree N°1151CM establishing an Inter-Ministerial Technical Committee to Control Miconia

and other Invasive Plant Species Threatening the Biodiversity of French Polynesia, chaired

by the Minister of Environment. It is composed of governmental agencies that are involved in

the prevention and control of introduced species, including the Environment, Research,

Agriculture, Equipment and Tourism Departments. They meet on a regular basis, and are

allowed to invite other non-government participants depending on their relevance to the

action plans. These may include research scientists, French Army representatives, nature

protection groups, elected officials, and representatives of local communities. The main goals

are to define short and long term control strategies, which may include finding manpower and

supplies, and determining priorities regarding public information, education, research, and

regulatory instruments.

30

3. Summary of existing strategy and programs on IAS

3.1 Public information and education

Several articles have appeared in the two local newspapers Les Nouvelles and La Dépêche, and several

local magazines. Local radio and TV have provided educational and informational time. Illustrated

posters and leaflets were recently produced. They include:

⇒

three different posters on Miconia prevention and control published by the Délégation à

l’Environnement and widely distributed to the high volcanic islands of French Polynesia which

could potentially be invaded. They were entitled “The Green Cancer” (Le Cancer Vert, 1989),

“Danger Miconia” (1991), and “Stop Miconia” (Halte au Miconia, 1993, prepared by the author);

⇒

a poster on the flora and fauna of montane rain forests in Tahiti published by the Délégation à

l’Environnement in 1996 in collaboration with the author, mentioning some introduced noxious

species, the swamp harrier (Circus approximans), Miconia (Miconia calvescensi), Lantana

(Lantana camara) and the thimbleberry (Rubus rosifolius);

⇒

an illustrated poster on biological invasion by alien plants and animals in French Polynesia, “Les

invasions biologiques: menaces pour la Polynésie française”, prepared by the author for the

Délégation à la Recherche in 1998;

⇒

a poster illustrating the thirteen invasive alien plant species threatening the biodiversity of French

Polynesia and some other potential plant invaders, prepared by the author for the Délégation à la

Recherche in 1999. It was jointly funded and published by the Délégation à la Recherche and the

Délégation à l’Environnement in 2002;

⇒

a leaflet in English entitled “Let Us Protect Our Islands” published in 2000 by the Minister of

Agriculture and the Service du Développement Rural to build foreign tourists’ awareness of the risk

of introducing plant and animal species to French Polynesia, and the need to declare any plant

product when they arrive in French Polynesia and when they travel between the islands; and

⇒

several leaflets on the fruit-flies present in French Polynesia (Bactrocera dorsalis, B. kirki, B.

xanthodes, B. tryonii) were published in 2001-2002 by the Minister of Agriculture and the Service

du Développement Rural. These show the current island distribution of the various flies and give

some recommendations on prevention and control.

3.2. Recent legislation and policy efforts

Several decrees contributing to IAS management in French Polynesia. were adopted by the Council of

Ministers of the Government of French Polynesia (Conseil des Ministres):

⇒

July 25 1996: Decree N°740 CM prepared by the Service du Développement Rural, prohibiting new

imports of 75 alien plant species (list prepared by the author) that are current or potential noxious

species. The Decree also includes a list of noxious insects such as the Chinese rose beetle

(Lepadoretus sinicus), the coconut hispine beetle (Brontispa longissima), the fruit-flies (Bactrocera

spp.) and the big headed ant (Pheidole megacephala) and a list of noxious fungi, arthropods,

nematodes, bacteria, viruses, and mycoplamas.

31

⇒

December 3 1997: Decree N° 1333CM prepared by the Délégation à l’Environnement, declaring

the carnivorous snail or rosy-wolf snail (Euglandina rosea) a threat to biodiversity. New

importation, breeding and transportation between islands is prohibited, and destruction authorized.

⇒ February 12 1998: Decree N°244CM prepared by the Délégation à l’Environnement. A total of

thirteen dominant invasive alien plants in French Polynesia including Acacia farnesiana, shoebutton

ardisia (Ardisia elliptica), trumpet tree (Cecropia peltata), Lantana (Lantana camara), false-acacia

(Leucaena leucocephala), molasses grass (Melinis minutiflora), Miconia (Miconia calvescens),

strawberry guava (Psidium cattleianum), thimble berry (Rubus rosifolius), African tulip tree

(Spathodea campanulata), rose apple (Syzygium jambos), Java plum (Syzygim cumini), and yellow

elder (Tecoma stans), were declared a threat to biodiversity. New introductions, propagation and

cultivation, and transportation within and between islands are strictly prohibited and the destruction

of these species is authorized.

⇒

February 9 1999: Decree N°171CM prepared by the Délégation à l’Environnement. Four alien

birds, the common myna (Acridotheres tristis), the red-vented bulbul (Pycnonotus cafer), the

swamp harrier (Circus approximans) and the great horned owl (Bubo virginianus) were declared a

threat to biodiversity.

3.3. Recent actions in the field

⇒

Manual and chemical Miconia control operations have been conducted on the island of Raiatea

since 1992, Tahaa since 1996, and Nuku Hiva and Fatu Hiva since 1997. The Inter-Ministerial

Technical Committee to Control Miconia and other Invasive Plants organized the Miconia control

campaign in the island of Raiatea in 1999, 2000, 2001 and 2002 in collaboration with the French

Army (80-90 soldiers for one week). More than 1,450,000 miconia plants including 1,600

reproductive trees were destroyed between 1992 and 2003, and the invasion was contained.

⇒

Fruit-fly chemical control conducted by the Service du Développement Rural in Tahiti in 1997,

1999 and 2000, and in the Austral and the Marquesas Islands since 1998 and 1999 respectively.

⇒

Rat control by poisoning is conducted by the Society of Ornithology of French Polynesia Manu

since 1998 in three valleys of Tahiti for the recovery of the Tahiti monarch or flycatcher.

⇒

Botanical field surveys were recently conducted by the author for the Délégation à la Recherche in

the islands of Bora Bora (Society Islands), Nuku Hiva and Fatu Hiva (Marquesas), Rurutu and

Tubuai (Austral Islands) in 1999 and 2000. The goals are to inventory and locate both native and

endemic plants and IAS.

⇒

Capture of a green iguana (Iguana iguana) of unknown origin (July 1999, town of Papeete) and of a

squirrel introduced as a pet on a Korean ship (August 1999, docks of Papeete) by the Zoo-sanitary

Section of the Service du Développement Rural and French Customs. In 2002, live snails (Helix

aspera) were found by the Plant Protection Section of the Service du Développement Rural in a

container from France.

⇒

Release in April 2000 of a Miconia-specific pathogen fungus (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

forma specialis miconiae) as a biocontrol agent in a test-zone on Tahiti.

32

⇒

Release in 2003 of a parasitoid wasp (Fopius arisanus (Braconidae)) to control fruit flies by the

Service du Développement Rural.

⇒

Project of the Service du Développement Rural to release biological control insects to control the

glassy-winged sharpshooter.

3.4. Prevention and monitoring efforts

⇒

The Inter-Ministerial Invasive Plants Committee notified the French Polynesian airline company

Air Tahiti Nui in May 1999 of the potential accidental introduction of the brown tree snake (Boiga

irregularis) from Guam. This airline company organized the first direct flight between Tahiti and

Guam during the Pacific Games in June 1999.

⇒

Post-release monitoring of the Miconia biocontrol pathogen agent in Tahiti since 2000 (conducted

by the author). In 2002, 10% of the inoculated Miconia plants died and 50% of them have serious

leaf or stem damages.

4. Government departments/agencies and other organizations concerned with IAS

⇒

Research and field surveys

Délégation à la Recherche

Ministère de la Culture et de la Recherche

Gouvernement de Polynésie française

B.P. 20981 Papeete

Tahiti