Julie Rugg and Alison Wallace

Centre for Housing Policy

University of York

Property supply to the

lower end of the English

private rented sector

1

Contents

Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................................6

Acknowledgements...............................................................................................................................................7

Executive summary ..............................................................................................................................................8

1: Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................8

2: Characteristics of tenant demand ........................................................................................................9

3: Landlord characteristics ..........................................................................................................................9

4: Financial decision-making ................................................................................................................... 11

5: The role of place ........................................................................................................................................ 12

6. Management practices in the housing benefit market............................................................ 13

7. Letting agents and other risk-absorbing intermediaries....................................................... 14

8. The impact of Covid ................................................................................................................................. 15

9. Landlord intent .......................................................................................................................................... 16

10. Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................. 18

1. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................... 19

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 19

Background to the study ............................................................................................................................ 19

Key trends ......................................................................................................................................................... 20

Regional variation in PRS growth ..................................................................................................... 20

Sectoral reconfiguration ........................................................................................................................ 21

Policy intervention ................................................................................................................................... 22

Objectives, aims and methods ................................................................................................................. 24

Secondary data analysis: tenants ...................................................................................................... 24

Secondary data analysis: landlords .................................................................................................. 25

Qualitative professional informant interviews .......................................................................... 25

Quantitative landlord data ................................................................................................................... 26

Qualitative landlord interviews ......................................................................................................... 26

Ethics ................................................................................................................................................................... 27

Report summary ............................................................................................................................................ 27

Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................................... 28

2. CHARACTERISTICS OF TENANT DEMAND .................................................................................. 29

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 29

Defining ‘the lower end’ of the market ................................................................................................ 29

2

Demographic characteristics ................................................................................................................... 31

Economic characteristics ........................................................................................................................... 33

Tenants in financial difficulties ............................................................................................................... 35

Length of tenancy .......................................................................................................................................... 36

Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................................... 37

3. LANDLORD CHARACTERISTICS ........................................................................................................ 38

Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 38

‘Lower end’ supply ........................................................................................................................................ 38

Landlord typology ........................................................................................................................................... 39

Accidental ..................................................................................................................................................... 40

Investment landlords .............................................................................................................................. 40

Portfolio landlords ................................................................................................................................... 42

Business landlords ................................................................................................................................... 43

Dynamics............................................................................................................................................................ 44

Tenant preferences ....................................................................................................................................... 45

Landlords averse to letting to tenants receiving housing benefit ..................................... 45

Landlords tolerating tenants receiving housing benefit ........................................................ 46

Landlords targeting tenants receiving housing benefit ......................................................... 47

Landlord survey ............................................................................................................................................. 48

Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................................... 49

4. FINANCIAL DECISION-MAKING......................................................................................................... 50

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 50

The purchase status of rental properties ........................................................................................... 50

Landlord finance strategies ...................................................................................................................... 51

The highly geared, ‘tumble through’ model ................................................................................... 51

The debt-averse, ‘pay down’ model ................................................................................................... 53

Use of commercial loans ........................................................................................................................ 54

Alternative portfolio-building strategies ...................................................................................... 54

Inheritance .................................................................................................................................................... 55

Mortgage-free portfolios ........................................................................................................................ 55

Tax changes ...................................................................................................................................................... 56

Stability and instability ............................................................................................................................... 57

Rent setting and minimising expenditure ......................................................................................... 58

Property quality ............................................................................................................................................. 59

Is supply financially sustainable? .......................................................................................................... 61

Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................................... 62

3

5. THE ROLE OF PLACE ............................................................................................................................... 64

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 64

The spatial dimensions of demand from lower-income households .................................... 64

Landlords in the housing benefit market ........................................................................................... 67

Strategic approaches .................................................................................................................................... 68

Strategic ‘incoming’ housing benefit landlords .......................................................................... 69

‘Local’ housing benefit landlords ...................................................................................................... 70

Property type ................................................................................................................................................... 71

Factors shaping local opportunities ..................................................................................................... 72

Changing demand ..................................................................................................................................... 72

Local authority intervention ............................................................................................................... 72

Short-term letting options .................................................................................................................... 73

Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................................... 73

6. MANAGEMENT PRACTICES IN THE HOUSING BENEFIT MARKET .................................. 75

Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 75

Target housing benefit markets .............................................................................................................. 75

‘Working’ housing benefit..................................................................................................................... 75

Benefit-dependent tenants................................................................................................................... 76

Vulnerable tenants ................................................................................................................................... 76

Nominated tenants ................................................................................................................................... 76

Letting to housing benefit recipients ................................................................................................... 76

Rent setting, shortfalls and arrears .................................................................................................. 77

Managing LHA/UC claims ..................................................................................................................... 78

Tenant support .......................................................................................................................................... 80

Changing the target HB market ............................................................................................................... 81

Reducing lettings to unemployed tenants .................................................................................... 81

Reducing lets to vulnerable tenants ................................................................................................ 82

Increasing lets to vulnerable tenants .............................................................................................. 82

Seeking to work with intermediaries .............................................................................................. 82

Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................................... 82

7. LETTING AGENTS AND OTHER RISK-ABSORBING INTERMEDIARIES .......................... 83

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 83

Letting agents in the HB market ............................................................................................................. 83

Letting agent experiences in the HB market ............................................................................... 85

Landlord use of letting agents ............................................................................................................ 86

Mediating agencies ........................................................................................................................................ 87

4

Size and reach of the mediated market .......................................................................................... 88

Mediating agencies and the landlord ‘offer’ ................................................................................. 89

Landlord use of mediating agencies ................................................................................................ 90

Rent insurance products ............................................................................................................................ 94

Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................................... 94

8. THE IMPACT OF COVID.......................................................................................................................... 96

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 96

Government measures ................................................................................................................................ 96

Welfare changes ........................................................................................................................................ 96

Changes to possession proceedings................................................................................................. 97

Deferred mortgage payments ............................................................................................................. 97

Rent arrears ...................................................................................................................................................... 97

Mortgage deferrals and other financial assistance ........................................................................ 98

LHA increases ............................................................................................................................................... 100

Change to possession proceedings ..................................................................................................... 101

Conclusion ...................................................................................................................................................... 103

9. LANDLORD INTENT .............................................................................................................................. 104

Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 104

Reduction in mortgage activity ............................................................................................................ 104

Portfolio intentions: the Private Landlord Survey...................................................................... 104

Portfolio intentions: respondent landlords ................................................................................... 106

Landlords who were expanding ..................................................................................................... 106

Landlords who were pausing or ‘static’ ...................................................................................... 106

Landlords who were selling.............................................................................................................. 107

Factors underlying a reduction in holdings ................................................................................... 108

Demography ............................................................................................................................................. 108

Financial reasons ................................................................................................................................... 109

Universal credit ...................................................................................................................................... 110

‘Regulatory burden’ .............................................................................................................................. 112

Hassle........................................................................................................................................................... 112

Risk ................................................................................................................................................................ 113

New entrants ................................................................................................................................................. 114

Conclusion ...................................................................................................................................................... 115

10. CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................................................ 116

Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 116

Market reconfiguration ............................................................................................................................ 116

5

The nature of HB-dominant markets ........................................................................................... 116

The mediated market ........................................................................................................................... 117

Reduced property supply........................................................................................................................ 119

Dynamic cohort effects........................................................................................................................ 119

Non-strategic HB lettings ................................................................................................................... 119

Stepping back from HB lettings ...................................................................................................... 120

Risk mitigation ............................................................................................................................................. 120

Conclusion ...................................................................................................................................................... 121

Appendix 1: Respondent landlord characteristics........................................................................... 122

Appendix 2: Additional figures and tables .......................................................................................... 124

Appendix 3: Quantitative landlord data................................................................................................ 128

6

Foreword

In 2018, the Nationwide Foundation funded the Centre for Housing Policy at the

University of York to deliver a review of the private rented sector in England and create

an accompanying report into vulnerability in the private rented sector. Coming out

strongly from this seminal work was evidence about how precarious the lowest end of

the private rented sector is, both in terms of how it operates as a market, and the

experiences of renters living there.

Critical questions that emerged from the 2018 review remain: what role is the private

rented sector expected and willing to play in the wider housing system? And how

sustainable is it? For the Nationwide Foundation, sustainable means that landlords are

able to operate their business, and renters are able to live in decent and affordable

homes.

This new research by the Centre for Housing Policy looks to start answering those

questions with a particular focus on the part of the private rented sector that is typically

occupied by renters in poverty, in receipt of housing benefit, on the lowest incomes or

paying the lowest rent.

What is clear to us from this research is that this lower end of the private rented sector

is not sustainable. In most of England, housing is simply unaffordable for private renters

on low incomes. Even in more affordable areas, the decisions being made by landlords,

letting agents and intermediaries about who they let to and how they operate their

businesses, are skewing the market, often disadvantaging renters on low incomes.

We know that many of these renters are particularly vulnerable to harm in the private

rented sector, yet there is simply nowhere else for them to turn. Until there are more

social rented homes, reform of the welfare system and changes to the private rented

sector, this problem will only get worse. We can no longer accept that the private rented

sector in its current form will continue to be able to deliver housing to renters on low

incomes.

Our thanks go to Dr Julie Rugg and Dr Alison Wallace for carrying out this thorough and

insightful research that can inform thinking and decisions relating to the private rented

sector. We hope stakeholders will find this new evidence about the characteristics of the

lower end of the private rented sector and its landlords, as interesting as we have.

Bridget Young, Programme Manager

The Nationwide Foundation

June 2021

7

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to the Nationwide Foundation for the opportunity to complete

this research project. We benefitted substantially from the guidance and support of Bridget

Young from the Nationwide Foundation, who always asks the most pertinent questions at

the right time. We are grateful for the contribution of many third sector and statutory

officers who carved out time to talk with us despite extreme work pressures. We received

data support from BDRC and UK Finance, and we also thank Property II8 for helping us to

contact landlords willing to answer our questions. Finally, we express gratitude to the many

landlords who offered frank discussion of their financial and business affairs.

As an independent charity, the Nationwide Foundation influences changes to improve

circumstances for those people in the UK who most need help. Its vision is for everyone in

the UK to have access to a decent home that they can afford, and its strategy seeks to

improve the lives of people who are disadvantaged because of their housing circumstances.

To do this, it aims to increase the availability of decent affordable homes. The Decent

Affordable Homes strategy began in 2013 and the Nationwide Foundation is committed to

this strategy until 2031.

Funding for this work, totaling £199,434, has been given as part of the Nationwide

Foundation’s Transforming the Private Rented Sector programme. The Nationwide

Foundation has a commitment to transforming the private rented sector so that it provides

homes for people in need that are more affordable, secure, accessible and are better

quality.

The Nationwide Foundation was established by Nationwide Building Society in 1997 as a

fully independent foundation. It is a registered charity (no. 1065552) and a company limited

by guarantee in England and Wales (no. 3451979).

8

Executive summary

Key messages are summarised in the boxes.

1. Introduction

• This report assesses the sustainability of property supply to the bottom end of the

private rented sector in England. The report defines ‘sustainability’ in terms of

property coming to the market at sufficient scale to replace properties that have

been withdrawn, supplied by landlords with stable business models and where

income is sufficient to undertake necessary repairs and maintenance.

• A great deal of research has considered the impact of austerity measures on tenants

living in the PRS. Little attention has been paid to the characteristics and behaviour

of landlords meeting the need for lower-rent housing. This report explores why

some landlords might express a ‘No DSS’ preference whilst others actively target

that market. A sustainable supply of affordable rental properties depends on

continued landlord engagement with this part of the sector, and the research also

examines letting intentions amongst this landlord group.

• In the absence of substantial investment in social housing, there is an expectation

that the PRS will continue to meet lower-income household need. This report

explores how far it is viable for private landlords to play that role, and whether

future supply will be robust and sustainable.

• This research is taking place at a time when PRS growth has faltered nationally

although there is substantial regional variation in terms of increase and contraction

in this part of the market. Sectoral reconfiguration has led to a refinement of

supply-side characteristics. There is increasing investment – including large-scale

institutional investment – in the ‘mediated’ market which secures access to PRS

properties for households in acute housing need. This interest reflects higher levels

of housing benefit that are often payable, for example, for temporary or exempt

accommodation.

• At the same time, the regulatory context for landlords has altered the complexion of

a market that has hitherto been regarded as relatively benign for small investors.

• The research is based on multiple methods and data sources including secondary

analysis of existing datasets, qualitative interviews with professional informants, a

short quantitative survey of landlords and detailed qualitative interviews with 55

landlords.

A number of policy changes have impacted on the PRS since 2012, and each

change has had the potential impact of reducing landlord willingness to supply

property to the bottom end of the market.

9

2. Characteristics of tenant demand

• There are a number of ways in which it might be possible to define the ‘lower end’ of

the private rented sector. Definition can rest on any of the following terms: the

household living in poverty, being in receipt of housing benefit, being on the lowest

incomes or paying the lowest rent. Taken together, all those features cover well

over half the rental market. However, lower-end demand is generally expressed by

one or two of these elements: private rented households in poverty are obviously in

the bottom third of households, but do not all claim housing benefit or have the

lowest rents. For the purposes of this report, it is important to note the lower end of

the PRS is not coterminous with all households receiving housing benefit.

• Landlords do not regard the bottom end of the market – however defined – as a

single market. Some landlords are willing to accept working tenants on lower

incomes but not in receipt of housing benefit. However, the introduction of

Universal Credit means that it is increasingly difficult to draw binary distinctions

between working/not working tenants since many tenants receive some benefit to

augment lower wages, and many landlords do let to ‘benefit-supported’ tenants.

• Tenants wholly dependent on housing benefit are more likely to have financial

problems than working lower-income tenants assessed in terms of – for example –

keeping up with bills. However, less than five per cent of tenants in receipt of

housing benefit were currently behind with their rent payment. Notwithstanding

these difficulties, across all economic and demographic types at the lower end of

the market, there tended to be similar proportions of households having stayed in

the same property for five years or more.

‘Lower end’ has multiple definitions and tenants have different characteristics

depending on those definitions. Working, ‘benefit-supported’ tenants are less

likely to be in financial difficulties than fully ‘benefit-dependent’ tenants who are

not in work because of their health, age or caring responsibilities.

3. Landlord characteristics

• For the purposes of this report, definition of landlord types is essential in order to

establish trends in decision making and in longer-term letting strategies. Landlords

are not a homogenous group. Further, classification has to be dynamic: landlords

move into, through and out of the market. A total of 55 landlord interviews,

analyzed in detail, indicates the ways in which the classification and the dynamics

played out at the bottom end of the market.

• Landlord classifications included accidental, investment, portfolio and business

landlords. None of the landlords who were interviewed were ‘accidental’ landlords in

the sense that their letting was short-term, but a number had not set out to be

landlords and so moved from that category to a more active engagement with the

market. ‘Investment’ landlords were defined principally in terms of whether or not

their income was derived from working for an employer or from pensions or similar

10

kinds of investment. ‘Portfolio’ landlords were working as landlords full-time, and

were generally hands-on, often with a background in building-related trade.

‘Business’ landlords were letting property and running ancillary property-related

businesses including letting agencies or property development. They often owned

more than one type of business. They were more likely to act in a ‘CEO’ capacity and

have staff to deal with property management and maintenance.

Landlordism is a dynamic state and includes accidental, investment, portfolio

and business landlords who are moving into, through and out of the rental

market.

• Landlords often moved from one category to another, and the number of lettings

they had was a poor indicator of the kind of landlord they were. This is because

holdings were dynamic: some landlords were actively growing their portfolios;

others had reached a species of more or less welcome plateau; and some were

selling down. The landlords who were interviewed varied in terms of age: some had

been letting property since the 1980s, and had built up their holdings following the

introduction of readily-available buy-to-let mortgages and low interest rates

following the Global Financial Crisis.

• A number of respondent landlords were very unwilling to let to tenants in receipt of

housing benefit, reflecting the wider sectoral preferences. The qualitative

respondents indicated that their preference reflected the fact that their rents were

set at some way above the LHA rates and were not affordable to tenants who

needed help to pay the rent. Other landlords viewed this kind of tenant as

problematic in relation to benefit bureaucracy, or as having personal characteristics

that were in some way undesirable.

• The majority of landlords in the qualitative sample - and a quarter of respondents in

the quantitative sample – were not averse to letting to tenants receiving LHA and/or

Universal Credit – but did not change their letting practices to accommodate the

benefit. For qualitative respondents, provided the rent was paid in full and on time,

the source of their tenants’ income was of no concern. This group included a large

number of landlords with ‘legacy lettings’: very long-standing tenancies which in

some cases had been inherited with the property, and where the landlord’s historic

commitment to the tenant extended to forbearance during times of financial

difficulty.

• The majority of landlords who were interviewed qualitatively were rather more

firmly in the housing benefit market: this was a target market, landlords were fully

aware of the LHA rates and set their rents in reference to those rates. Landlords had

preferences within the housing benefit market. These preferences might include:

Working tenants who were lower income and benefit-supported rather than

wholly benefit dependent.

Single parents or pensioner households who were wholly reliant on benefit,

and where benefit receipt was not fluctuating as a consequence of

employment income.

11

Single older individuals who were likely to be seeking accommodation in

shared properties, and at the higher ‘over-35s’ LHA which is paid irrespective

of whether the property is shared or a studio; and

Vulnerable people with long-term health issues including drug and alcohol

dependencies, where it was possible to for the landlord to secure direct

payment of housing benefit via an Alternative Payment Arrangement.

The ‘housing benefit market’ is not one market. Some landlords tolerate tenants

receiving housing benefit but do not set their rent through reference to the Local

Housing Allowance rates or charge or their management practices. Landlords

who actively target tenants in receipt of housing benefit do both of those things,

but also have letting preferences depending on the degree to which tenants rely

on benefit.

4. Financial decision-making

• Landlords had two principal strategies in building their portfolios. Many used a

‘tumble-through’ model, whereby properties available at below-market value, often

because of condition, were purchased and refurbished. These properties were then

remortgaged to release the additional equity, with that money then used as a

deposit on another property. This model depended on locating properties at the

right price. The availability interest-only mortgages contributed substantially to the

attraction and profitability of this model, and landlords in this group tolerated a high

loan-to-value ratio on their properties.

• Other landlords were more likely to expand steadily, looked to repay their

mortgages and sought to achieve a debt-free portfolio certainly by retirement age.

The difference in approaches generally reflected personal attitudes towards debt.

• A small number of landlords had built up their holdings using alternative strategies

which included operating ‘sale and rent back’ schemes in the 2000’s. Recourse to

this strategy had led to rapid growth of holdings for a handful of respondent

landlords.

• It is notable that some landlords were mortgage free either because they had, over

time, succeeded in paying down their debt or because properties were inherited or

paid for in cash from rental income or other business dealings.

• Recent taxation changes had variable impact on landlords depending on their

financial strategies. Many landlords were unmortgaged, had small portfolios or

shared their tax liability with their partner to keep them below the relevant tax

threshold. Some landlords had transferred their properties into company ownership

which meant that the tax change did not apply. Landlords who had seen an impact

were considering their ongoing letting strategy (see Chapter 9).

• The majority of respondents had a robust financial strategy and had built sufficient

contingency to deal with external shocks. Many brought additional competencies to

their lettings which minimized financial risks, including trade skills, property

knowledge or general business, finance or legal acumen. Landlords who were less

12

stable were often at an early stage in their letting experience, and had insufficient

contingency funds to deal with unanticipated repairs.

• Landlords who were letting at the bottom of the market tended to pursue a strategy

of cost minimization rather than rent maximization. The most common tactic for

reducing costs was minimizing turnover and voids which meant attracting and

retaining good tenants through charging a lower-than-market rent, infrequent rent

increases and prompt attention to repairs and maintenance. Indeed, expenditure on

property condition was regarded as an essential element of a good business model.

However, the relationship between longer-term tenancies at the bottom of the

market and higher incidence of non-decency remains unexplained.

Landlords who were targeting the bottom end of the PRS focussed on cost

minimisation rather than rental maximisation, with strategies aimed at reducing

voids and tenancy turnover.

• Arguably, much of the current supply of property to the lower end of the market is

not commercially replicable: investor landlords were generally happy to accept a

lower rent because they had taken out interest-only mortgages and current interest

rates are low; similarly, many landlords with long-term, ‘low-income’ tenancies

tolerated a lower rent because the properties were not mortgaged. Furthermore,

much of the sector is reliant on a cohort of landlords who accrued substantial

holdings during a distinctive period of more flexible finance and benign taxation

which is unlikely to return.

A great deal of current supply to the bottom end of the market is being let in

circumstances that are not easy to replicate: in particular, there is an aging cohort of

landlords with portfolios that were built at a time of flexible financing and benign

tax treatment. New entrants to the market will not be able to build their holdings in

the same way.

5. The role of place

• There is substantial regional difference in the proportion of lettings to tenants in

receipt of housing benefit, and geographic variation in the principal reasons why

tenants need to apply for assistance. There were seventeen local authorities where

tenants receiving benefits comprised over 50 per cent of all households in the PRS.

Nine per cent of all HB tenants were in a ‘HB-dominated’ market. Using a threshold

of 40 per cent as the definition, 28 per cent of all HB tenants were in a HB-dominant

market.

• Landlords who were actively engaged in letting to HB tenants were often

responding to spatial opportunities created by the LHA rates themselves. Landlords

bought properties where yield was calculated using the LHA rates. In some

13

locations, the very slight increases to LHA rates since 2012 took place against

stagnation in market rents. These circumstances created pockets of low house

prices but LHA rates offering more satisfactory yields. Almost all the larger business

landlords had identified these opportunities and were operating in this type of

location, using their own paid staff to manage properties.

• Other landlords targeting the HB market had properties in their ‘home’ location,

and were more likely to rely on a combination of highly localized knowledge – for

example, to identify purchase opportunities – and cost minimization strategies.

These landlords were, more often, portfolio landlords who were actively managing

their own stock and themselves working on property renovation and maintenance.

There are areas of the country where the LHA rates are higher than market rents,

and larger business landlord activity was targeted at those areas.

6. Management practices in the housing benefit market

• Landlords who targeted the bottom end of the market tended to be the more

experienced portfolio and business landlords, and each had their own preferences

within the housing benefit market. Tenants who received some benefit support but

were in work were favoured by some landlords as being a group least in need of

active management, but some landlords were not happy with the fluctuations in

income and benefit entitlement that employed tenants could experience. ‘Steady’

tenants included young families and older households who were not seeking work

and whose income did not change. Some landlords regarded more vulnerable

tenants as being preferable, since it might be possible to apply for an Alternative

Payment Arrangement (APA) and so have rent paid directly. There were landlords

whose management plans were geared towards taking tenants who were

nominated by the local authority’s homelessness team, where an APA was

guaranteed and the local authority offered some level of tenant support.

• Landlords letting at the bottom of the market were generally of the view that

setting the rent at the LHA rate was easiest to manage least likely to result in rent

arrears. There was little point in setting up tenancies to fail. Large business

landlords employed staff to manage rent collection proactively and deal with arrears

quickly before they accrued. Landlords who knew their tenants well, tended to be

flexible about missed payments where they knew that tenants would resolve the

debt over time.

• A common risk-mitigation strategy was to require tenants to provide details of a

home-owning guarantor who would make good any arrears, and some landlords

indicated that they had pursued those guarantors where tenants left owing

substantial amounts of rent.

14

Landlords requiring the tenant to provide a home-owning guarantor was a

common risk-mitigating strategy.

• Many HB landlords were actively involved in their tenants’ HB claims. A number of

landlords had experience in working with the LHA system and were dismayed by

their early experiences under Universal Credit (UC). In particular, landlords were

unhappy with the fact that their communication with benefit staff had been

curtailed. This limited landlords’ ability to help tenants when problems arose with

their benefit. There were particular problems when more vulnerable tenants were

transferred onto UC and received their HB payment themselves.

• Some landlords saw arranging APAs as central to their business strategy, and only

took nominations where the nominating agency could guarantee that an APA would

be put in place.

• Landlords in the HB market regarded tenant support as part of good management,

and likened their role to social workers. This was particularly the case where

landlords had more vulnerable tenants. One larger business landlord employed a

tenancy manager who had previously worked in social housing.

• It was notable that, for many landlords, early experiences with UC were provoking a

change in their target client group. In some instances, this mean a move towards

more independent, working ‘benefit-supported’ tenants. Landlords cited problems

with securing direct payments and tenants moving themselves off APAs, but were

also clearly unhappy with the fact that they no longer had a working relationship

with the local authority HB department.

Landlords in the HB market judged tenant groups in terms of the level of risk and

options for risk mitigation. Alternative Payment Arrangements (APAs) could

offset the risks of letting to more vulnerable tenants. Where landlords had poor

experiences with APAs they were likely to change their target market.

7. Letting agents and other risk-absorbing intermediaries

• The Private Landlord Survey 2018 indicated that letting agents were much more

willing than landlords to let to tenants in receipt of housing benefit, in being more

likely to have some knowledge of the benefit system and less likely to indicate that

mortgage or insurance companies had restrictive policies in this regard.

• Respondent landlords indicated that letting agents were often involved in housing

benefit letting, for example if the property was located at some distance from the

landlord’s home, or if the landlord had a background in trades or felt they did not

have the skills or aptitude for the tenancy paperwork.

• An estimated 10 per cent of the HB market is ‘mediated’ and involves statutory or

third sector agencies procuring properties under contract to local authorities.

Interviews took place with large-scale mediating agencies operating in the private

15

sector and in the third sector, and these indicated that property procurement to

meet housing need is increasing in scale and profitability as an enterprise.

Mediating agencies are playing an increasing role in the housing benefit market,

and are becoming oriented towards large-scale procurement and management of

rental property backed by investment capital.

• Landlords also dealt with more traditional ‘help to rent schemes’, which absorbed

some of the risks involved in letting to a tenant on lower income by offering

assistance with setting up the benefit claim or – if required – a APA, and giving

support to ensure that the tenancy continues.

• Landlords had variable experiences of these schemes. Accounts were coloured by

‘horror stories’ which were evidently common currency amongst landlords.

Landlords who were happy with the arrangements they had made included a

London landlord who was receiving incentive payments to take tenants; and a

landlord dealing with a homelessness charity, where the level of tenancy support

had reduced risk and his own burden of management.

• An equal number of landlords had less positive experiences and were, as a

consequence, stepping away from the housing benefit market. Poor experiences

included the mediating agency failing to give the promised support to a problematic

tenant, which in some instances left the landlord accruing rent arrears, dealing with

anti-social behavior or having to evict the tenant.

Landlord experiences of poorly-supported ‘help to rent’ schemes often led to

their stepping away from the HB market.

• It was notable that some landlords were using rent insurance products to mitigate

the risk of rent arrears. Some landlords who no longer accepted tenants in receipt of

benefit cited higher insurance premiums as the principal reason.

8. The impact of Covid

• The government introduced a number of measures to support the PRS in response

to the pandemic. The two measures of principal concern to landlords at the lower

end of the market were changes in LHA rates and changes to possession

proceedings. Note that fieldwork with landlords took place during the summer

months of 2020, between the first and second lockdowns.

• Few landlords reported that they were having serious problems with rent arrears as

a consequence of the pandemic. Landlords who had tenants who were wholly

reliant on benefits saw no change, and indeed some increased their rents to take

advantage of the uplift in LHA rates.

16

• Recourse to mortgage deferral was low, and many landlords resisted this measure

given possible impact on their ability to remortgage in the future.

• Landlords were most concerned about changes to possession proceedings, which

they generally referred to as a ‘suspension’ of s21 which allows landlords to evict

without specifying a reason. Landlords reported difficulties with some tenants who

had stopped paying the rent or whose anti-social behavior was causing difficulties,

or cases where proceedings against a tenant had been halted.

• Landlords were generally of the view that the suspension had left them vulnerable

to criminal tenants who entered into tenancies with no intention of paying the rent,

and who sought to use the property as a base for illegal activity. This aspect of Covid

fed most strongly into decisions framing landlord letting intentions.

• Some landlords had paid problematic tenants so they would leave. This measure

reduced the amount of arrears that would have accrued and immediately brought to

an end problematic anti-social behaviour that was often affecting neighbours.

• Landlords also tended to tighten up their vetting procedures, and no longer ‘took

risks’ with tenants they felt might fall into difficulties with paying the rent. Risk

mitigation measures included more routinely requiring tenants to provide home-

owner guarantors.

The Covid impact felt most strongly by landlords was limitation in the ability to

use s21 as a means of evicting highly problematic tenants. Some landlords had

simply paid those tenants to leave principally as a means of reducing the

accumulation of unrecoverable arrears.

9. Landlord intent

• Data from the Private Landlord Survey 2018 indicates that the intention to sell

property and/or leave the market was more marked amongst larger landlords and

landlords agreeing that housing benefit tenants were a group they would let to.

• Amongst the respondent landlords, almost all the business landlords and handful of

investment and portfolio landlords were planning to expand their holdings (n=15).

Of the remaining 40 landlords, 22 were not intending to make any change to their

holdings in the short or medium term, and eighteen were selling down.

• Landlord intent was reviewed in terms of their continuing letting generally, and

their continuing to let in the housing benefit market. The landlords who were

expanding their lettings included larger business landlords who were letting in

locations where the LHA rate was higher than the market rent; landlords who had

secured nomination agreements with guaranteed APAs; and landlords who were

taking nominations with attached incentive payments. Other landlords who were

expanding indicated that none of their new properties would be let to people

receiving UC.

• Landlords with no immediate plans to buy or to sell included those who were happy

with the size of their holdings: they had reached a ‘sweet spot’ in terms of tax

17

liability and a manageable portfolio. Other landlords had reached a point where

regulatory and tax changes had reduced their willingness to increase their holdings.

• Seventeen landlords were selling property. The process of disinvestment was slow,

and sale generally took place when the property became vacant. None of the

landlords sold tenanted properties. Landlords were most likely to sell the properties

they regarded as problematic, and that generally included properties they had let at

the bottom of the market.

There were multiple reasons why landlords were choosing to exit the market,

which often worked in combination. Taxation changes, introduction of UC and a

swathe of new regulations had increased the risks attached to letting whilst at

the same time reducing profitability.

• There were six factors underlying a landlord selling down or exiting the market:

Demography: many landlords were ‘baby boomer’ landlords who had built

their holdings during the prime ‘by-to-let’ years and were now beyond

retirement age. These landlords were often selling properties at the rate of

one a year, and using the released equity to improve their quality of life.

Finance: the taxation change had impacted on some landlords, who saw the

profitability of their lettings reduce substantially. In these circumstances one

common strategy was to sell down to a smaller number of unmortgaged

properties.

Universal Credit: many landlords with extended experience of Local Housing

Allowance were extremely unhappy with the operation of UC and looking to

reduce their HB lettings. The direct payment of rent to tenants was a key

issue for landlords dealing with tenants they regarded as being incapable of

managing their own finances.

‘Regulatory burden’: the increased burden of regulation was felt to be

problematic for some landlords. None had issues relating to the need to

regulate property quality and management, but some felt that compliance

timescales – for example, for energy efficiency – could be unrealistic, and

penalties for non-compliance were excessive. Investor landlords were

particularly wary of inadvertent non-compliance.

Hassle: for a number of respondents, the financial returns from letting

property were not commensurate with the level of ‘hassle’. Portfolio and

investor landlords who were actively managing their own properties were

working long hours and effectively on-call 24/7. Investor landlords in

particular were beginning to view more passive investment options as

preferable, given similar levels of return.

Risk: landlords were of the view that the market now presented a harsh

environment for small landlords. The previously listed factors were felt in

combination, and the prospective abolition of s21 signaled a substantial

increase in the risks attached to letting property.

• There is evidence of a slow-down in new entrants to the market. The PLS 2010

indicated that 22 per cent of landlords had been letting for three years or less; in

18

2018 the comparable figure was 9.5 per cent. Willingness to let to housing benefit

claimants was lower amongst those newer landlords.

• Amongst the respondent landlords, the newer entrants to the market were much

more likely to have set up their businesses to be tax-efficient under the new regime

and establishing frameworks to accommodate UC regulations. However, there was

general agreement across landlords that although the market presented the

opportunities to make good returns, the risks attached to letting had multiplied.

Larger landlords who were seeking to expand in the HB market were more likely

to be targeting localities where LHA rates were above market rates, and let to

tenant groups where APAs could be secured.

10. Conclusion

• This report has focused on property supply to the lower end of the PRS and included

a detailed exploration of demand-side characteristics, market geography and

landlords’ financial decision making, management practices and portfolio

intentions. The conclusion indicates a number of new developments in the market

which are concerning, including market reconfiguration and landlord use of

risk-mitigation strategies which are likely to exacerbate the exclusion of tenants

who are already disadvantaged in the market. There is evidence of a lowering in the

scale of supply to replace properties being withdrawn from the market in areas

outside HB-dominant markets. Growth is evident within the HB-dominant markets.

Outside these locations, response to the increase in risk attached to letting has led

to a reduced willingness to let to people in receipt of benefit. Landlords are much

less willing to take chances. This trend is being amplified by a mismatch between

the number of landlords exiting the market and those entering: taxation, financial

and regulatory change has resulted in a less amenable context for small

landlordism.

19

1. INTRODUCTION

Introduction

The private rented sector (PRS) is a part of the housing market that meets multiple

purposes. Reduced investment in social housing and the sale of social housing stock via

right to buy have led to an increased reliance on the PRS by low-income households. The

PRS expanded steadily from the turn of the 21

st

century, but growth has stalled in recent

years. A wide range of policy changes has created new contexts for landlords letting to low-

income households. Housing Benefit payments under the Universal Credit system and a

freeze in Local Housing Allowance rates have not been welcomed by landlords, who are

also accommodating taxation changes and an increase in operation costs following a

number of regulatory interventions. It is generally understood that landlords are

withdrawing from the market. If landlords are withdrawing from letting or more specifically

from letting at the bottom end of the market, and with no corresponding increase in social

housing supply, one likely consequence will be an increase in levels of homelessness.

This report assesses the sustainability of property supply to tenants at the bottom end of

the PRS. Here, ‘sustainability’ is viewed in terms of properties coming to this part of the

market at sufficient scale to replace properties that have been withdrawn, and supplied by

landlords with stable business models. In undertaking this assessment, the research has

focussed on the characteristics of landlords operating in this part of the market and

explored their financial and management strategies. The report – based on detailed

analysis of qualitative interviews and supported by secondary data analysis – presents

substantial new data on the behaviours, attitudes and future intentions of landlords letting

to tenants on lower incomes.

Background to the study

In the last twenty years, the PRS has expanded to house lower-income households whose

needs might, in earlier decades, have been met in social housing. Landlords will generally

have a target tenant group, and some aim to meet demand from lower-income tenants.

Indeed, there is a ‘housing benefit (HB) market’, with landlords operating management

practices that take benefit receipt into account. These landlords will tolerate a delay in the

first rental payment to allow for the time for the initial application, accept on-going rental

payments in arrears and set their rents at or close to the Local Housing Allowance (LHA)

rates.

1

When they were introduced in 2003, LHA rates were originally set at the 50

th

percentile of

rents for a range of household sizes. The rates were adjusted to the 30

th

percentile in 2011.

Since that time, the LHA rates have become increasingly disconnected from any

1

J. Rugg (2007) ‘Housing benefit and the private rented sector: a case study of variance in rental niche

markets’, in D. Hughes and S. Lowe (eds.) The Private Rented Housing Market: Regulation or Deregulation?

Aldershot: Ashgate, 51-68.

20

relationship between the bottom 30

th

percentile of rents, as a consequence of capped

increases and a four-year freeze from 2016/17.

2

These restrictions were part of austerity

measures designed to reduce welfare expenditure. The regulations have restricted the pool

of affordable properties, since possible landlord responses to the measure include requiring

tenants to make an additional payment to meet a shortfall between the LHA rate and the

market rent, and refusing to let to tenants who rely on benefits.

3

A note on terminology

In this report, ‘Housing Benefit’ or HB will comprise a generic reference for benefit

support with housing costs; Local Housing Allowance (LHA) refers to the system of

assistance for private renters in operation between 2003 and the introduction of

Universal Credit (UC) in 2013. Housing assistance within UC is still paid according to LHA

rates defined for different household sizes; the rates are set for each of the 152 Broad

Rental Market Areas in England.

Reports have highlighted the impact on tenants of affordability issues in the PRS and of the

increasing incidence of homelessness as a consequence of landlords deciding not to renew

assured shorthold tenancies often as a consequence of rent arrears and benefit-related

problems.

4

Little attention has been paid to the characteristics and behaviours of landlords

meeting the need for lower-rent housing. Moral judgement of landlord unwillingness to

accommodate ‘DSS’ tenants has overshadowed the need to understand why landlords

might express that preference, the circumstances in which landlords do let to lower-income

tenants, and intentions with regard to continuing to supply that market. In the absence of

substantial investment in housing available at social rent levels, there is an expectation that

the PRS will continue to meet lower-income household need. This report explores how far it

is viable for private landlords to play that role, and whether supply will be robust and

sustainable.

Key trends

There are three major contexts defining the operation of the bottom end of the PRS:

substantial regional variation in patterns of growth and stagnation; broad sectoral

reconfiguration; and an increased flow of policy intervention that has introduced

regulations impacting on landlord finances, costs and management practices.

Regional variation in PRS growth

According to the English Housing Survey, the proportion of households in the PRS grew by

around one percentage point between 2013/14 and 2018/19. In understanding supply-side

2

CIH (2018) Missing the Target, Coventry: CIH.

3

Shelter (2020) Stop DSS Discrimination: Ending Prejudices against Renters on Housing Benefit, London:

Shelter.

4

S. Fitzpatrick, H. Pawson and G. Bramley et al. (2018) The Homeless Monitor: England 2018, Edinburgh:

Heriot-Watt University; K. Reeve, I. Cole and E. Batty (2016) Home: No Less Will Do. Homeless People’s Access

to the PRS. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University.

21

characteristics, relative tenure proportions are less relevant than absolute growth. The

number of households in the PRS nationally has increased roughly in line with population

growth, but there has been substantial regional difference. Table 1.1 indicates that,

between 2013/14 and 2018/19, the number of households in the PRS has grown markedly in

some regions, whilst falling in others. The North East region has seen a particularly high

level of increase – by 22.4 per cent – compared with an absolute drop in numbers in both

the Yorkshire & Humberside and the East Midlands region.

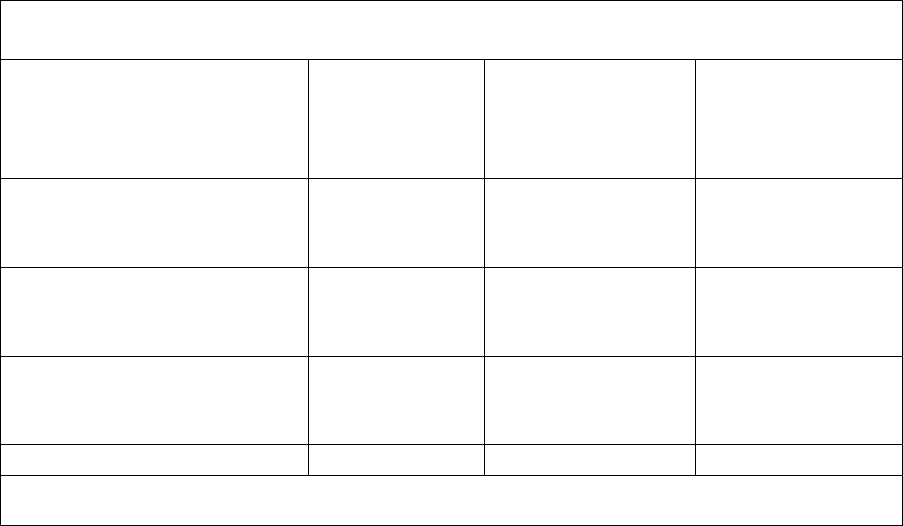

Table 1.1: All PRS households: growth in number by region (000’s)

2013/14

2018/19

Percentage growth, 2013/14-2018/19

North East

165

202

+22.4

North West

547

571

+4.4

Yorkshire & Humberside

445

427

-4.0

East Midlands

368

359

-2.4

West Midlands

347

405

+16.7

East

423

437

+3.3

London

1,014

964

-4.9

South East

651

713

+9.5

South West

418

474

13.4

Total

4,377

4,552

+3.9

Source: English Housing Survey

Sectoral reconfiguration

PRS growth has slowed down nationally, but the market is reconfiguring. Stakeholder

interviews indicated a number of key trends that will have a direct impact on the lower end

of the market. These include change in the nature of supply-side characteristics and the

identification of large-scale investment opportunities in meeting the needs of lower-

income renters. The interest of larger players in this market is challenging presumptions

that landlordism is or will continue to be a ‘cottage industry’. Major trends identified in the

contextual stakeholder interviews include:

• Growing institutional investment in properties meeting the needs of low-income

households, where it is possible to build a substantial portfolio under single

management. There was evidence of institutional purchase of properties for

‘squeezed middle’ renters at below market rates.

5

• A number of firms specializing in managing rental portfolios on behalf of

institutional investors with ‘patient capital’ that are satisfied with low dividends

secured over the long term, particularly where there is evidence that investment

meets social need.

• The expansion of build-to-let into regional cities and increasingly focused on the

creation of competitively priced rental family homes in private ‘estates’.

5

Also see e.g. L. Heath (2021) ‘Investment firm acquires 95 homes from house builder’, Inside Housing, 3 Mar.

22

• The general expansion of affordable rental products supplied by housing

associations and local authorities which will draw demand from the middle of the

private rental market.

• Reconfiguration of ‘student’ cities, as large-scale investment in purpose-built

student accommodation absorbs demand previously met by landlords offering

‘street’ properties: these landlords are exiting the market or letting to lower-income

tenants.

• Financialisation of the Temporary Accommodation (TA)/mediated market: including

third sector and local authority investment in TA. This includes the emergence of

large-scale commissioning of rental property procurement either to confederations

of charities or to commercial providers.

• Expansion of the exempt accommodation model which offers intensive housing

management funding to HMO providers who include support with accommodation.

This funding is not subject to LHA caps.

All these factors will impact on the opportunities available to landlords seeking to meet

demand at the bottom of the market. These trends will be revisited in Chapter 11.

Policy intervention

The sector has been subject to a succession of policy interventions that have included tax

changes, regulatory change relating to property quality and management, and radical

alteration in the delivery of assistance with housing costs. These interventions are briefly

summarised below, with an emphasis on the element of change carrying major importance

from a private landlord perspective.

Finance Act 2015

S24 of the Finance Act 2015 introduced a tax change aimed at landlords who personally

held buy-to-let mortgages, loans and overdrafts relating to property: tax calculations would

be based on rental income with no adjustment made to accommodate finance costs.

Essentially, landlords would no longer be able to offset mortgage interest costs against tax

liability. The change was introduced in tranches of 25 per cent over four years. In some

instances, the adjustment pushed some landlords into a higher tax bracket. Landlords

holding their property in a property company were not affected.

Housing and Planning Act 2016

Regulatory changes in force from April 2017 have introduced a range of civil penalties for

non-compliance with offences under the Housing Act 2004. As an alternative to

prosecution, local authorities can apply a maximum civil penalty of £30,000. All landlords

are required to meet licensing requirements as they relate to houses in multiple occupation

(HMOs), but some local authorities have introduced additional and selective licensing

schemes that extend the reach of that licensing. In 2019, 44 local authorities were

operating some kind of selective licensing scheme which included all rental property within

a defined boundary and required landlords to pay a licence fee for each of their properties

within that boundary.

6

6

Lawrence, S. (2019) An Independent Review of the Use and Effectiveness of Selective Licensing, London:

MHCLG.

23

Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards

From April 2019 it was no longer permissible to let or renew tenancies on property rated F

or G in terms of energy efficiency. Landlords with properties rated at this level are required

to spend up to £3,500 to bring those properties to at least an E rating. The Government has

expressed the intention to implement an incremental increase to bring all let properties up

to band C by 2030.

7

Electrical Safety standards

The Electrical Standards in the Private Rented Sector (England) Regulations 2020, in force

from 1 July 2020, requires all landlords to arrange electrical safety inspections every five

years. This measure applies to all tenancies created on or after 1 July 2020.

Immigration Act 2014

From February 2016, landlords and letting agents are obliged to determine the immigration

status of prospective tenants to ensure that they have leave to remain in the UK. Under

what is generally known as the ‘right to rent’ legislation, landlords letting to someone who

they had reason to believe did not have a right to stay in the UK may be subject to

imprisonment or an unlimited fine.

Tenant Fees Act 2019

The Tenant Fees Act 2019 applies to all tenancies created or renewed on or after 1

st

June

2019, and severely curtails the fees that might be chargeable to the tenant by either the

landlord or the letting agent. Landlords will be required to bear the cost of any tenant

referencing.

Welfare Act 2012

The Welfare Act 2012 introduced Universal Credit (UC) which combines six working-age

benefits into one single payment, paid to the applicant monthly. The payment includes a

housing allowance based on the LHA rate for the household. Roll-out of UC has been

gradual, and it has recently been reported that 100 per cent coverage of all households

eligible for UC is unlikely to be achieved before 2022. There are two principal changes

brought by UC, compared with the earlier LHA system. All payments are made directly to

the tenant unless an ‘Alternative Payment Arrangement’ (APA) is made to transfer the

rental element directly to the landlord. APAs can be arranged at the outset if a tenant is

deemed to be in a ‘Tier 1’ category which includes the tenant being homeless or in

temporary accommodation or having addiction problems. Once a tenancy has started,

APAs can also be arranged if a tenant falls eight weeks behind with their rent. A second

major change is that UC is administered through job centres rather than by local

authorities. Landlords will no longer have access to a local authority HB officer to assist

with problems relating to a particular claim. Queries are dealt with centrally, or via job

coaches at job centres.

Covid-19 interventions

One final set of interventions has been introduced in response to the Covid pandemic. The

changes have included landlords being required to give a minimum of six months’ notice to

7

https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/improving-the-energy-performance-of-privately-rented-

homes

24

seek possession. In addition, there has been a moratorium on s21 ‘no fault’ evictions: this

measure was introduced in March 2020 and at the time of writing had been extended until

the end of May 2021. It is permissible for landlords to bring possession orders against

renters in cases of severe rent arrears or anti-social behaviour. Courts are still hearing cases,

but bailiff actions have been paused aside from some exceptional circumstances.

In addition, and of particular importance to landlords letting to tenants in receipt of HB,

there has been a temporary readjustment of LHA rates to the 30

th

percentile of local rents.

This measure was intended to improve affordability at the lower end of the market and

reduce the incidence of rent arrears. These measures were in place during the fieldwork

period for this project.

Objectives, aims and methods

This report is based on a study which was funded under the Nationwide Foundation

Transforming the Private Rented Sector programme. The objectives for the research were

broad and highly exploratory, and included:

• definition of demand and supply-side characteristics of the lower end of the PRS,

including mapping its geography; and

• assessing whether and how far the bottom end of the PRS constitutes a sustainable

part of the wider private rental market.

The study comprised a mixed-methods research programme including:

• secondary analysis of existing datasets relating to demand for rental

accommodation from low-income tenants;

• secondary analysis of the MHCLG Private Landlord Survey (PLS);

• analysis of a small suite of questions added to Q1 of the BVA BDRC Landlord Panel

survey;

• interviews with nineteen national, regional and local professional informants with

expertise in supply at the bottom end of the market; and

• detailed qualitative interviews with 55 landlords.

Covid restrictions meant that it was difficult to secure a sufficient numbers interviews with

letting agents to allow for detailed analysis of this issue from a letting agent perspective.

Secondary data analysis: tenants

Secondary analysis relating to tenants included the Family Resources Survey (FRS) and

DWP administrative data relating to housing allowances accessed through the Stat X_Plore

site. The FRS is a continuous survey of 19,000 households per annum providing information

about household finances and circumstances for the DWP. The data were used to explore a

number of ways of defining the lower end of the market by using the bottom third of

regional household incomes (equivalised); the bottom third of regional private rents that

were adjusted to reflect the property size; poverty before housing costs (using household

incomes below 60 per cent equivalised household incomes) and indicators of receipt of HB.

25

This project used FRS to establish who lived in the lower end of the private rented sector,

what resources they brought to the market and their geography, in comparison to the

wider rental sector. The analysis was undertaken using the 2017/18 data, which was the