NOTESNOTES

FINTECHFINTECH

BigTech in Financial Services:

Regulatory Approaches

and Architecture

Parma Bains, Nobuyasu Sugimoto, and Christopher Wilson

NOTE/2022/002

FINTECH NOTE

BigTech in Financial Services:

Regulatory Approaches

and Architecture

Prepared by Parma Bains, Nobuyasu Sugimoto, and Christopher Wilson

January 2022

©2022 International Monetary Fund

BigTech in Financial Services:

Regulatory Approaches and Architecture

Note 2022/002

Prepared by Parma Bains, Nobuyasu Sugimoto, and Christopher Wilson

Names: Bains, Parma, author. | Sugimoto, Nobuyasu, author. | Wilson, Christopher (Christopher Lindsay),

author. | International Monetary Fund, publisher.

Title: BigTech in financial services : regulatory approaches and architecture / prepared by Parma Bains,

Nobuyasu Sugimoto, and Christopher Wilson.

Other titles: Regulatory approaches and architecture. | FinTech notes (International Monetary Fund).

Description: Washington, DC : International Monetary Fund, 2022. | January 2022. | Note 2022/002 |

Fintech notes. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781557756756 (paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Financial services industry -- Law and legislation. | Financial services industry --

Technological innovations. | Finance -- Technological innovations. | Banks and banking -- Information

technology.

Classification: LCC K1397.F56 B35 2022

Fintech Notes oer practical advice from IMF sta members to policymakers on important issues. The

views expressed in Fintech Notes are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views

of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

Publication orders may be placed online or through the mail:

International Monetary Fund, Publication Services

P.O. Box 92780, Washington, DC 20090, U.S.A.

T. +(1) 202.623.7430

publications@IMF.org

IMFbookstore.org

elibrary.IMF.org

BigTech in Financial Services: Regulatory Approaches and Architecture

Abstract

1

BigTech firms are gradually entering the financial sector and becoming important service providers, particu-

larly in emerging markets. BigTechs have entered financial services using platform-based technology to

facilitate payments and more recently expanded into other areas, such as lending, asset management,

and insurance services. They accumulate data from their nonfinancial and financial activities and draw on

consumer data held in dierent parts of their business (such as via social media). BigTechs are applying new

approaches to existing financial services products and services such as underwriting using big data and are

also applying machine learning for their key business decisions, such as pricing and risk management across

multiple financial sectors. Incumbent financial firms have also increased their reliance on BigTech firms to

host core IT systems (for example, cloud-based services, which have the potential to improve eciency and

security). This rapid and significant expansion of BigTechs in financial services and their interconnectedness

with financial service firms are potentially creating new channels of systemic risks.

To achieve eective implementation and multiple objectives of financial regulation and supervision, a

hybrid approach, combining a mix of entity- and activity-based approaches, is needed. Home supervisors

should establish an entity-based approach to cover the global activities of a BigTech group, while host

supervisors could in principle address local risks and concerns mainly through activity-based regulations.

Cross-sector and cross-border cooperation are key in determining the future of the regulatory architecture.

However, it can take several years before regulators have achieved a suciently robust legal and regulatory

framework to address all risks arising from BigTech in financial services, and short-term solutions may be

needed. In the interim, regulatory authorities should actively use all existing regulatory powers to manage

risks, while BigTech should adopt and improve governance frameworks through industry codes of conduct

and enhanced disclosures. Options should be explored to promote global consistency in the treatment

of BigTechs, through existing or new global bodies with a broad mandate. We recommend that the 2012

Principles for the Supervision of Financial Conglomerates be reviewed to address regulatory gaps.

1

This note was prepared by Parma Bains, Nobuyasu Sugimoto and Christopher Wilson, with inputs from Fabiana Melo and

Anastasiia Morozova (all MCM).

iv International Monetary Fund—Fintech Notes

BigTech in Financial Services: Regulatory Approaches and Architecture

Contents

Abstract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .iii

I. Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

II. BigTech in Financial Services—Key Elements. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Reversing the Unbundling—Faster, Higher, Stronger . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Interconnectedness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Concentration of Cloud Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

III. Key Considerations in Regulatory Approaches . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

The Existing Regulatory Frameworks and BigTechs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

IV. Regulating BigTechs—Now and Later . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Implications for Regulatory Architecture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Potential Regulatory Approaches . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Key Challenges along the Way . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

V. Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

VI. Annex 1: Definitions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23

VII. References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .24

Box 1. Dierent Trends of BigTech Expansion into Financial Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Box 2. Disclosure of BigTech Financial Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

Box 3. Case Studies of Current Entity- and Activity-Based Regulatory Approaches to BigTech. . . . . . . . . . .18

Table 1. Key Risks of BigTech . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

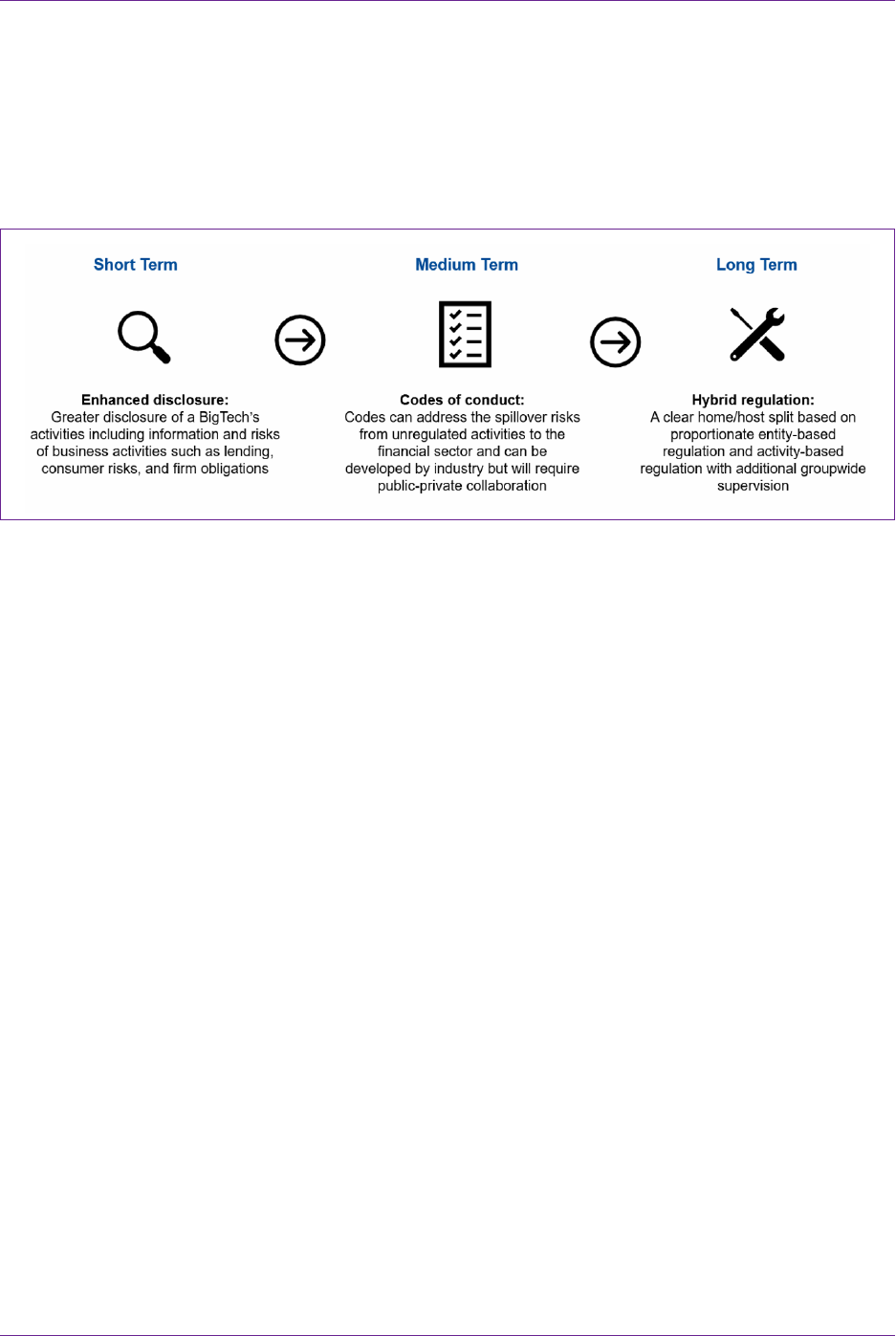

Figure 1. Short, Medium, and Long Term Regulatory Frameworks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

vi International Monetary Fund—Fintech Notes

BigTech in Financial Services: Regulatory Approaches and Architecture

I. Executive Summary

2

International Monetary Fund and The World Bank sta developed the agenda in 2018 (International Monetary Fund [IMF]

and The World Bank 2018).

Fintech is changing the ways in which financial services are delivered, and rapid advances in technology

pose new challenges to financial regulation. Fintech developments have typically been characterized by the

unbundling and decentralization of services, rapid changes of technologies and business models, strong

economies of scale and cross-border and cross-sectoral expansion, and a focus on retail services. These

developments present challenges for regulators: Traditionally, entities are granted permission to provide

financial services based on a supervisory assessment where they need to meet certain minimum standards.

Therefore, financial intermediation has traditionally been provided by regulated financial service firms,

and regulation is put in place to mitigate excessive risk taking. Fintech has upended this traditional link

between provision of financial services and regulation of risk taking. Regulatory authorities have aimed at

safeguarding financial stability while not stifling innovation and more recently have focused on the chal-

lenges brought on by BigTech.

With strong and diverse business models, BigTechs are increasing their presence and market share in

financial services. These larger firms are able to utilize their existing user base and big data; advanced analyt-

ical technologies, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning; cross-subsidization; and economies of

scale to deliver new technologies and innovative products and services. In particular, BigTech firms benefit

from competitive advantages stemming from the so-called data analytics, network externalities, and inter-

woven activities loop (Crisanto, Ehrentaud, and Fabian 2021). This business model enables BigTech firms to

quickly increase their market share in financial services and become, directly or indirectly, important players

in financial intermediation.

The expansion of BigTech into financial services has the potential to bring both benefits and risks (Adrian

2021). The presence of BigTech entities in a market can potentially increase financial inclusion, lower costs of

products and services, and create greater consumer choice in the short term. However, BigTech expansion

in financial services has the potential to create risks to financial stability in three broad ways: (1) by carrying

out several activities that increase risk when carried out cumulatively, (2) through operational interconnect-

edness with financial incumbents, and (3) through financial interconnectedness with financial incumbents. In

addition, BigTech expansion to financial services is creating risks from the unique combinations of financial

and nonfinancial services. Even if traditional financial risks may not be material in their global business model,

other risks (such as concentration, contagion, and reputation risks) when combined may have systemic impli-

cations in local financial markets.

The Bali Fintech Agenda (BFA)

2

provides a framework for regulatory authorities to help them harness

the benefits of fintech while mitigating risks. The BFA consists of 12 policy elements that can help authori-

ties capture the benefits that BigTech operations can bring into financial markets, such as embracing the

promise of fintech; ensuring open competition and a commitment to open, free, and contestable markets;

fostering fintech to increase financial inclusion; and developing robust financial and data infrastructure to

sustain those benefits. It can also guide authorities toward mitigating the risks of BigTech by better moni-

toring developments in the market, adapting regulatory frameworks for the stability of the financial system,

and encouraging regulatory cooperation across borders.

Financial regulators need to consider both short- and long-term impacts on the provision of financial

services. The impact of BigTech on incumbent financial firms is mixed so far: In some cases, BigTech is disrupting

markets, and in others, it is partnering with incumbents. Experience suggests that regulatory approaches that

allow for the emergence of fintech start-ups across jurisdictions foster competition in the short term. However,

2 International Monetary Fund—Fintech Notes

the

same regulatory environment may favor the participation of BigTechs in financial services, allowing them

to leverage new data sets and their own proprietary data to promote cross-subsidization and potentially lead

to monopolistic structures that could hinder competition in the long term. Careful consideration of longer

term eects is needed to develop new, or adjust existing, regulation to provide a level p laying fi eld for

incumbents, fintech start-ups, and BigTech, while mitigating risks to financial stability, market integrity, and

consumer protection.

To achieve these policies in the long term, a hybrid approach to regulation is needed whereby home

supervisors establish entity-based regulation complemented with host supervi-sors employing activity-

based regulations. The entity-based approach allows the regulatory framework to be principle based, flexible,

and proportionate to the risks of the entity and its wider group. The activity-based approach may facilitate a

level playing field by applying specified rules equally to all firms in a given activity. In most jurisdictions, an

entity-based approach is deployed for prudential regulation, whereas an activity-based approach is more

common for market conduct regulation. BigTech business models are creating new complex risks, and

neither of these approaches on their own can fully address the potential risks associated with the global

reach of BigTechs. A hybrid approach is indispensable to address the risks of BigTechs, where home

supervisors establish a proportionate entity-based regulatory approach to cover BigTech as a group, while

host supervisors apply an activity-based approach supplemented with additional groupwide supervision

by the home. Broader coordination with nonfinancial regulators and competition authorities will be

required, particularly for home regulators, to mitigate systemic risks generated from BigTech activity.

Even though there are several options to implement regulations for BigTech, implementation is not

straightforward. While new regulatory frameworks may be warranted for BigTech (such as entity-based regu-

lation that reflects the unique risks of BigTech for home regulators), it will likely be several years before legal

and regulatory adjustments are concluded.

3

In the interim, regulatory authorities should actively use all

available existing regulatory powers. For example, financial regulators could undertake indirect supervision

through regulated entities in the group and by proper implementation of nonbank and conduct regulations.

It will be important to actively coordinate with other authorities to prepare and address risks of potential

entrance of BigTech in multiple jurisdictions, activities, and business lines. Meanwhile, BigTechs should be

encouraged through public-private collaboration to adopt and improve governance frameworks through

industry codes and enhanced disclosure.

Options should be explored to promote global consistency in the treatment of BigTechs through existing

or new global bodies. Any international coordination body would need to have a broad mandate to address

some of the issues discussed here, especially those that lie outside the remit of the financial sector standard

setters. We recommend that the 2012 Principles for the Supervision of Financial Conglomerates be reviewed

to address regulatory gaps and mitigate new risks (including systemic risk) arising from conglomerates, such

as B igTech g roups.

3

Promising work on data policy has begun (Carriere-Swallow and Haksar 2019; Haksar and others 2021).

BigTech in Financial Services: Regulatory Approaches and Architecture

II. BigTech in Financial Services—Key Elements

4

The Financial Stability Board defines BigTech as “large companies with established technology platforms” (Financial

Stability Board [FSB] 2019). In addition, the Financial Stability Institute has defined BigTech as “large technology companies”

(Crisanto, Ehrentaud, and Fabian 2021).

There is no agreed-upon definition of BigTech,

4

but generally, these platform-based business models focus

on maximizing interactions between a large number of mainly retail users. BigTech entities are typically

large technology conglomerates with extensive customer networks and core businesses across markets, for

example, in social media, internet search, and e-commerce. An outcome of their operation is the creation,

capture, storage, and utilization of user data. This data drives a further range of services that generates even

greater user activity and, ultimately, the creation of more data.

BigTechs rely on these strong network eects to grow their business and services. These services generate

network eects through interaction, user activity, and the generation of ever greater amounts of data. The

more users interact with the services oered by BigTechs, the more attractive the services become to other

users. The data can be sold to third parties or analyzed in-house to improve existing services or generate

new service propositions and additional revenue streams.

The use of technology in financial services to generate innovation has, in many countries, been driven by

smaller firms, better known as financial technology (fintech) start-ups. Initially, fintech start-ups were the key

drivers of innovation in financial services, unbundling services by large financial institutions and delivering

greater consumer choice. These fintech start-ups have driven innovation in areas such as payments, credit

referencing, asset management, and insurance services. Many of these start-ups have benefited from regu-

lations intended to foster competition (for example, the European Union’s Payments System Directive and

various regulatory sandboxes). However, fintech is not just provided by start-ups; it can also be provided by

financial incumbents, especially through partnership with fintech start-ups.

More recently, the expansion of BigTech into financial services has been observed. In many circum-

stances, major fintech start-ups that achieve scale have been acquired by BigTech groups and continue

to oer innovative financial services through BigTech platforms. While the emergence of fintech already

presented challenges to the regulatory and supervisory community to promote the safety and soundness

of the financial system, the entrance of BigTech in financial services brings additional layers of complications

given its characteristics (Table 1).

Large technology conglomerates utilize their existing user base, cross-subsidization, and economies of

scale to deliver new technologies and innovative products and services. The key aspects that distinguish

BigTech from fintech start-ups are the number of users, the number of jurisdictions in which they operate,

and the revenue and scope of activities. Fintech delivered by BigTech tends to be more impactful on the

market given the size of the entities. It can drive greater change and bring new ideas and technologies to

market faster, more cheaply, and with greater coverage and availability than incumbent financial institutions.

BigTech expansion to financial services shows unique characteristics, especially when compared to the

entry of fintech start-ups. The entry of fintech start-ups into financial services has normally been charac-

terized by the unbundling and decentralization of services, rapid changes of technologies and business

models, a strong economy of scale, a predominant retail and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SME)

focus, and a clear cross-border and cross-sectoral expansion. BigTech’s expansion to the financial sector

reverses the first two characteristics: unbundling and decentralization.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the trend toward digitalization of retail financial services and

changes in market structure. During the pandemic, most market participants have attempted to adopt a

more online business model. In turn, the pandemic strengthened the role of BigTechs, larger fintech-driven

4 International Monetary Fund—Fintech Notes

firms, and digitally prepared incumbents. Market shares of BigTechs and larger fintech-driven firms increased

during the pandemic at the expense of smaller fintech start-ups and less digitally prepared incumbents.

These changes in market structure result in benefits and risks. Benefits include improved financial inclusion

for underserved populations, cost savings, and eciencies leading to improved consumer welfare. Risks

include consumer abuse owing to low levels of financial literacy, potential monopolistic behavior, and

financial instability.

The pace and scale of BigTech expansion within financial services has the potential to create risks to

financial stability in three broad ways: (1) through expansion across financial services sectors carrying out

several activities that in isolation might not create systemic risk but can increase risk when carried out

cumulatively, partially due to lack of eective cross-sectoral regulation; (2) through interconnectedness

with financial incumbents (for example, between loan-originating BigTech and commercial banks that are

providing funding); and (3) through the provision of single systemically important activities like the cloud

or systemic payments infrastructures. Taken together, these three risks can create scenarios where BigTech

becomes “too big to fail.”

REVERSING THE UNBUNDLING—FASTER, HIGHER, STRONGER

New technologies have enabled fintech start-ups to unbundle financial services by taking part in a small

number of activities. These include payments, account aggregation, lending, saving, and so on. These

start-ups utilize a low-cost base, a lack of legacy systems, and new technologies to deploy these individual

products or services globally, which has allowed them to achieve rapid growth. This generally increases

competition in financial services and provides consumers with greater choice and, often, cheaper and more

tailored products.

BigTechs have access to large proprietary data sets as well as the experience, talent, and technology

to control and act on large data sets, which have allowed them to reverse the unbundling delivered by

fintech start-ups. BigTechs already have a large global user base through the provision of products and

services outside of financial services, such as e-commerce, social media, instant messaging, and telecom-

munications. BigTechs can leverage these data sets more cheaply and in a more tailored way with the

benefits that cross-subsidization and economies of scale can bring. BigTechs can use their knowledge of

consumer preferences obtained through their other business areas, such as consumer spending habits

and credit worthiness, to oer financial services to customers who may be underserved by traditional

lenders. These advantages are leading to BigTechs reversing the unbundling that fintech start-ups have

achieved, providing a wide range of financial services within the group. The economic and social benefits

of financial deepening, such as encouraging financial inclusion, can be compelling in the short term, but

bundling can also limit consumer choice in the long term.

The expansion of BigTech into financial services has initially been focused on payments and proprietary

systems but has gradually incorporated companies and services. Payments form an important component

in the core services oered by BigTechs. Digital payments are a significant growth area in financial services

in general, and many BigTechs had existing platforms that could be utilized to quickly oer digital payment

services to a large user base (for example, Facebook Pay). Some BigTech entities (like Amazon and Alibaba)

began operations as e-commerce platforms that bring together buyers and sellers, and so expanding into

payments was a natural progression. Additionally, in some jurisdictions, for many years payments regula-

tion has been focused on supporting new entrants, ultimately facilitating the entrance of BigTechs. BigTechs

have developed their own proprietary systems in financial services but have also acquired smaller fintech

BigTech in Financial Services: Regulatory Approaches and Architecture

start-ups. In 2020, BigTechs invested over $2 billion in fintech companies, with Google’s parent Alphabet

alone generating 23 fintech investments.

5

BigTechs are able to leverage their knowledge of consumer preferences through their other business

areas, as well as consumer spending habits and credit worthiness, to oer lending services to customers

who may be underserved by traditional lenders. This can be useful in countries where consumers might

lack documentation to prove income or creditworthiness or where otherwise traditional credit informa-

tion might be less reliable. Moreover, BigTechs can utilize existing relationships with SMEs, as well as

knowledge of their business obtained through core services (such as providing an e-commerce platform

for these firms), to provide lending services to entities that incumbent financial institutions might consider

risky. BigTech lending to SMEs is largest in Asia but is gaining traction globally.

BigTechs are achieving a level of integration across sectoral services that could be more attractive to

users than the “one-stop service” oered by traditional financial conglomerates. Traditionally, financial

service providers that oered only limited services (such as lending firms) and limited integration of cross-

sectoral services were not attractive to customers. Even though traditional financial conglomerates have

sought to provide multiple services at one stop, data sharing and integration of services have often been

limited to each sector and service. While BigTechs still form a relatively small part in the total provision of

payments, insurance, and lending, strong network eects and a large existing base mean their share in

each sector can rapidly grow with much higher integration and the provision of attractive services across

the sectors.

Proposed BigTech-led initiatives such as so-called global stablecoins could expand BigTech coverage in

this space further. Given the large existing user base and potential for strong network eects, the launch of

new initiatives in the payments space could lead to products and services that might be potentially systemic

at launch. In addition, in low-income and emerging markets, stablecoins issued by BigTech and denomi-

nated in advanced economies’ hard currencies could become attractive as investment products. Where

these initiatives are based on closed networks with high barriers to entry or limited ability for others to

participate, such initiatives could lead to greater market power for infrastructure owners/administrators and

fragmentation of existing payment infrastructures (FSB 2020).

Insurance is another sector within financial services where BigTechs have naturally expanded and where

they may have several competitive advantages. They are able to build on existing services of product

protection and warranties provided in core operations and use these experiences to oer tailored insurance

products, competing with (and at times partnering with) established insurers and newer InsurTechs. BigTechs

often have several competitive advantages when it comes to the provision of insurance. For example, they

are able to leverage access to proprietary data from social media, chat functions, and other businesses that

allow them to better determine risks of consumers and firms in ways that financial incumbents and fintech

start-ups aren’t able to do. Importantly, research suggests that consumers are increasingly more likely to

purchase insurance from BigTechs, with the share of consumers growing from 27 percent to 44 percent

between 2016 and 2020 (World InsurTech Report 2020).

5

For example, the 2021 acquisition of Pring, a Japanese payments processor, is the latest in a line of payments acquisitions,

including Softcard, Zetawire, and TxVia, providing Alphabet with a stronger presence in payments networks and payments

technology.

6 International Monetary Fund—Fintech Notes

BOX 1. Dierent Trends of BigTech Expansion into Financial Services

The expansion of BigTech into financial services has occurred simultaneously in dierent countries,

although in dierent ways. In advanced economies, the expansion tends to focus on payment and

lending services where other nonbank entities are also actively expanding. Robust and comprehen-

sive regulation in banking and insurance services seems to be a factor behind this route of expansion.

In emerging markets, the scope of BigTechs’ expansion seems to be wider and includes banking,

insurance, and investment services.

In the United States, BigTechs with large market capitalization are expanding payment and credit

business both domestically and globally. Entities like Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, and Microsoft

have all expanded into financial services, with the largest presence in payments and credit. Three

of these firms (Alphabet, Amazon, and Microsoft) also provide cloud services for regulated entities.

In other advanced economies, BigTech expansion is still in early stages. In Japan, entities like NTT

docomo and Rakuten are entering financial services, such as payments, securities, and insurance,

although at a slower pace compared with the United States.

In China, BigTech has a greater presence in financial services across banking, payments, lending,

insurance, and investment. BigTech operations in financial services are more established and of

greater systemic importance since these entities often provide direct financial services to retail

customers but also partner extensively with commercial banks. Alibaba (through Ant Group),

Tencent, and Baidu are the Chinese BigTech entities with greatest reach.

In other emerging markets, BigTech is also making inroads into financial services in South America

(through Mercado Libre) and in east Africa and the Indian subcontinent through telecommuni-

cations firms Safaricom and Jio. In all these instances, BigTechs are able to outcompete smaller

fintech start-ups and sometimes benefit from regulatory frameworks that allow them to outcompete

incumbent financial institutions.

6

6

For further reading regarding BigTech expansion into financial services, see two publications by the FSB: BigTech in

Finance: Market Developments and Potential Financial Stability Implications (FSB 2019) and BigTech Firms in Finance in

Emerging Market and Developing Economies (FSB 2020).

INTERCONNECTEDNESS

When providing consumer loans, some BigTechs are partnering with commercial banks. While BigTechs can

compete with financial institutions, in most cases a cooperative arrangement is observed, particularly in low-

margin banking services. This has allowed BigTechs to gather further customer data and open new revenue

streams, while allowing fintech start-ups and incumbents to connect with new customers. BigTechs leverage

their large user base to deliver consumer lending to individuals who might be underserved or excluded, with

the potential eect of improving financial inclusion. BigTechs can reduce their risk exposure by delivering

loans in conjunction with a commercial bank and by providing only the consumer interface. Commercial

banks may also benefit from a more diversified loan portfolio with dierent segments and locations of clients.

Another example includes the proposed Diem Network, in which Meta plays a potentially key role as a network

member and wallet service provider, but financial institutions are partners that fulfill critical functions, such as

issuance, redemption, and market making.

However, partnership arrangements could create moral hazards and result in excessive risk taking by

BigTech lenders. In some cases, the direct risk exposure of BigTechs compared to the commercial bank may

look very small. Some examples indicate BigTech participation to be as low as 2 percent of a loan, where

BigTech in Financial Services: Regulatory Approaches and Architecture

98 percent of the loan, and risk, is borne by the partnering commercial bank. BigTechs can also charge

transaction fees to the commercial bank, which further increases their share of the revenue while keeping

risk exposure to a minimum. In such arrangements, BigTechs could have biased incentives to increase the

volume of lending with lower credit quality if commercial banks don’t conduct proper credit risk manage-

ment and establish appropriate data and loss-sharing arrangements.

Interconnections in the investment space can also give rise to systemic risk. The provision of money

market funds (MMF) is an area that has seen significant BigTech interest in recent years, particularly in east

Asia. MMFs are required to invest customers’ funds in high-quality and short-term assets such as short-

term government bonds or other highly rated issuers’ bonds. In the second half of the last decade, with

interest rates at historic lows, some MMFs oered by BigTechs began oering higher returns than bank

deposits. Those products are generally integrated into payment services, where excess balances are auto-

matically allocated to MMF investments and users can easily shift back and forth between using the balance

for payment or MMF investments.

BigTech-related MMFs in emerging markets are exposed to additional risks. BigTech services that

integrate payment and MMF seamlessly allow the investors to quickly withdraw cash on demand and

pay for goods and services. However, assets invested by MMFs may not be as liquid as cash and highly

liquid securities, even in advanced economies. Thus, the product is exposed to higher liquidity mismatch

risks than those of advanced economies. In addition, safety nets, such as central bank liquidity facilities

and deposit insurance, are generally not available to MMFs oered by BigTechs. Retail MMF investments

integrated with payment services, which require full and immediate redemption to cash, can create new

risks and contribute to concerns around contagion and interconnectedness, a key reason why regulatory

authorities have begun tightening their rules around the practice.

Systemic risk can also arise from the increasing interconnectedness of BigTech with other market partici-

pants such as financial market infrastructures (FMIs) and central counterparties (CCPs). Payment systems and

investment services developed and operated by BigTechs could have increasing exposures and potential

contagion to FMIs and CCPs. For example, Alipay and WeChat Pay are interconnected with NetsUnion

Clearing Corporation in China, and Google Pay has a direct connection with Unified Payments Interface and

Immediate Payment Service in India.

CONCENTRATION OF CLOUD SERVICES

The cloud is the virtual delivery of computing services, including servers and storage, analytics, and intel-

ligence, and poses unique systemic risks given the industrywide services provided. It powers many services

that consumers take for granted, such as content streaming (including music and television), media storage

on smartphones, and online games. It also powers the operations of entities across financial services,

including banks, insurers, investment managers, and start-ups.

7

There are normally three general functions

of the cloud: software as a service (SaaS), infrastructure as a service (IaaS), and platforms as a service (PaaS).

SaaS allows the hosting and delivery of applications that are managed by third-party vendors; IaaS allows

access to storage, networking, and virtualization; and PaaS provides software and hardware applications

that the user can build upon. The Bank of England, in a 2020 survey, estimated that more than 70 percent of

banks and 80 percent of insurers rely on just two cloud providers for IaaS (Bank of England 2020). Globally, 52

percent of cloud services are provided by just two BigTechs, while over two-thirds of services are provided

by the top four BigTechs (Richter 2021).

This concentration highlights the reliance of the financial sector on the services provided by BigTechs.

Interruptions or delays in the service have the potential to create large-scale issues in financial services.

7

For a comprehensive discussion of cloud employment in financial services, see Cloud Computer: A Vital Enabler in Times

of Disruption (Pujazon and Carr 2020).

8 International Monetary Fund—Fintech Notes

The failure of a service or one of these firms could create a significant event in financial services with poor

outcomes for markets, consumers, and financial stability. Cloud services are also provided to nonfinancial

sector firms, and in these sectors the provision of cloud is also deeply concentrated. Operational disruption

of large cloud service providers could have material contagion impacts not only to the financial sector but

also to the wider economy. There is clear concentration in critical services provided by BigTechs to financial

institutions and the potential for excessive reliance on a small number of cloud providers without viable

alternative options. The importance of these services means that, in some respects, BigTechs are already

“too big to fail.”

Table 1. Key Risks of BigTech

TYPE OF RISK IMPACT OF BIGTECH

Financial stability

y Expansion across financial sectors carrying out several activities that in

isolation might not create systemic risk but can increase risk when carried out

cumulatively

y Interconnectedness with financial incumbents

y Carrying out a single systemically important activity, such as cloud provision

or operating payments infrastructure

Consumer protection

y Reduced consumer choice through “rebundling”

y Market dominance that could lead to innovation being replaced by markups

y Lack of appropriate disclosure of activities, partnerships, or regulatory

protection

y Free/cheaper services provided through capturing/storing consumer data

Market integrity

y Challenges of regulation, supervision, and enforcement

» against BigTechs located in other jurisdictions

» against BigTechs with core businesses in nonfinancial sectors (for example,

e-commerce)

Financial integrity

*

y BigTech platforms that could facilitate cross-border fraud, theft, and money

laundering

y End-user unawareness where BigTechs operate blockchain-based propositions

Source: IMF sta .

* Financial integrity risks are beyond the scope of this paper, but for completeness some of the key impacts on financial integrity

of BigTech expansion to financial services have been added.

BigTech in Financial Services: Regulatory Approaches and Architecture

III. Key Considerations in

Regulatory Approaches

8

Some regulators are exploring interim measures to overcome the inherent limitations of the activity-based approach.

For example, UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) conducts market studies across industry price caps, which can be an

alternative to enforcement.

The Bali Fintech Agenda is a framework for helping authorities harness the benefits of new technologies and

business models while mitigating risks. In relation to BigTech, several BFA policy elements are particularly

important. Policy Element I (embracing the promise of fintech) and Element II (enabling new technologies to

enhance financial services provision) speak to the potential benefits BigTech can generate. Policy Element III

(reinforcing competition and commitment to open, free, and contestable markets), Element IV (ensuring the

stability of domestic monetary and financial systems), Element VI (adapting regulatory frameworks and super-

visory practices), and Element XI (encouraging international cooperating and information sharing) can all be

used as guidelines to mitigate against the risks generated by BigTech.

A robust regulatory framework should lay the foundation for eective supervision of financial institutions,

and while approaches dier across jurisdictions, two approaches are prevalent: entity-based regulation and

activity-based regulation.

y Entity-based approach is when regulations are applied to licensed entities or groups that engage

in regulated activities (such as deposit taking, payment facilitation, lending, and securities under-

writing). Requirements are imposed at the entity level and may include governance, prudential, and

conduct requirements. Implementation of those regulations is supported by a number of supervisory

activities (such as osite monitoring and onsite inspections). The entity-based approach can be built

on principle-based regulations that allow more flexibility, relying on governance arrangements and

oversight. Importantly, a continuous engagement between supervised firms and supervisors allows

for the monitoring of the buildup of risks and the evolution of business models. Supervisors normally

have a range of early actions that can be taken to modify firms’ behavior that could lead to excessive

risk taking and instability. Supervisors can take enforcement actions (such as fines and revocation of

licenses), but there is usually a ladder of interventions to achieve supervisory goals.

y Activity-based approach is when regulations are applied to any person or firm that engages in

certain regulated activities, for example, facilitating the buying and selling of investments or operating

lending activities. Those regulations are typically used for market conduct purposes and are generally

prescriptive, and compliance is ensured by fines and other enforcement actions. Many regulations

prohibit certain activities under specified conditions. In some respects, the activity-based approach

may encourage competition by requiring that only relevant regulatory permissions are needed to carry

out certain activities. However, the approach needs to define activities very precisely, which could

create regulatory arbitrage opportunities—and may not be able to capture rapidly changing fintech

activities. It could have negative impacts on innovation, as the prescribed rules may not be technology

neutral. Supervisors may issue warnings before taking enforcement actions, but other than that there

is less room for supervisors to take actions before proceeding to enforcement.

8

Because of the heavy

reliance on enforcement, the activity-based approach is not generally suitable for early supervisory

action to modify risky behavior by the firms. It is also not very eective for cross-border activities,

unless global regulators consider regulatory approaches that are closely aligned, and international

agreements allow for cross-border enforcement actions.

10 International Monetary Fund—Fintech Notes

y Hybrid approach combines elements of both activity- and entity-based regulation depending on the

nature of each jurisdiction’s regulatory structure and whether the jurisdiction houses the headquar-

ters of a firm or hosts their activities. A hybrid approach would use both activity- and entity-based

regulations with clear allocation of the responsibilities between home and host jurisdictions and close

cooperation among the regulators so that it may reap the benefits of the two approaches. Entities

would be subject to licensing by home jurisdictions and would be subject to other requirements,

including activity-based requirements imposed by host regulators. Close cooperation between home

and host supervisors would enable regulators to ultimately implement and enforce both global and

local requirements. Monitoring and risk identification with close cooperation among supervisors

would allow the detection of systemic risks arising from the combination of activities generated across

the group. The hybrid approach is necessary to achieve the underlying principle of “same services/

activities, same risks, same rules, and same supervision.”

Most financial institutions are subject to both entity- and activity-based regulations. Banking and—to a

lesser extent—insurance regulations are built with an entity-based approach. On the other hand, securi-

ties regulations have been developed with a more activity-based approach. In traditional financial markets

where banks and insurers are the main players, those activities are subject to both entity- and activity-based

regulations. In practice, the distinction between activity- and entity-based approaches is blurred, with regu-

lators often using entity-based measures (such as business improvement orders, intensive inspections, and

enhanced monitoring) to enforce activity-based regulations.

The IMF had previously (IMF 2014) recommended a “mixed approach”—similar to the suggested hybrid

approach—to address systemic risks posed by shadow banking. There are some similarities between shadow

banking and BigTech. For example, both have grown outside the regulatory perimeters to have potential

systemic implications. While each individual entity and service may not pose systemic issues, the combina-

tion of the entities and services create systemic risks. Some entities and functions of both shadow banking

and the BigTech ecosystem can easily relocate their headquarters and main activities to other jurisdictions

where regulations are less robust.

All regulatory approaches involve inherent policy trade-os. There is sometimes a trade-o between

eciency and stability in financial regulation. Competitive markets are ecient but may pose risks to

financial stability because tougher competition depletes margins and prevents banks from building buers.

Regarding BigTech, there are additional trade-os, for example, between anonymity (privacy) and allowing

data access to private providers (eciency) as well as between anonymity (privacy) and data sharing for

prudential purpose (stability; Feyen and others 2021). The entity-based approach can be principle based

and flexible. It helps supervisors develop an understanding of risks across activities. It can be more tailored

to cover risks arising from a combination of activities (such as deposit taking and lending, which enables

maturity and liquidity transformation). Therefore, entity-based regulation works better for financial stability

and prudential requirements, although it can be problematic where the regulatory perimeter is not clear.

On the other hand, the activity-based approach is applicable to any individual or firm who conducts partic-

ular activities, regardless of their licensing status, and enforcement tools are traditionally limited to fines.

Therefore, activity-based regulation can be simpler and more prescriptive, which may help to ensure a level

playing field among the entities conducting the same activities.

A hybrid approach could provide supervisors with additional flexibility in tailoring the regulatory

framework to suit the new contours of the financial system. While conceptually appealing, successful imple-

mentation requires close coordination between prudential and conduct regulators. In the hybrid approach,

both approaches can complement each other to achieve the competing objectives of financial regulation.

BigTech in Financial Services: Regulatory Approaches and Architecture

However, this approach needs close coordination between prudential and conduct regulators, which is not

always easy regardless of regulatory architecture.

Dierences in mandates and objectives between prudential and conduct regulators pose additional chal-

lenges for closer coordination. Prudential and conduct regulators face dierent challenges. On the one

hand, prudential regulators tend to be proportionate to systemwide risks and focus more heavily on large

firms and large transactions to assess firm and systemwide risks. On the other hand, for conduct regulators,

the most serious conduct incidents could emerge in the smallest transactions (such as SME loans and sales

to seniors). Equally, too much activity-focused supervision may fail to identify the systemwide risks (not

seeing the woods for the trees). Therefore, although both prudential and conduct regulators are shifting

toward risk-based supervision, prudential risk and conduct risk often require dierent skills and supervi-

sory frameworks. Coordination between prudential and conduct regulators can be challenging given their

dierent mandates, and it is important to keep in mind that conduct regulations are also crucial for the safety

and soundness of the financial system—as the subprime loan crisis in 2008 clearly demonstrated.

THE EXISTING REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS AND BIGTECHS

Existing regulatory frameworks can aect competition by creating an unlevel playing field between

financial incumbents and BigTechs. Deposit-taking institutions (banks) are subject to comprehensive regu-

latory obligations (macro- and microprudential, conduct, anti–money laundering/countering financing of

terrorism (AML/CFT),

9

reporting, and so on). This is because they typically provide three fundamentally

important services—deposit taking, lending, and payment infrastructure services—and as a result they may

play a systemic role in many jurisdictions. The regulatory requirements address potential systemic risks,

which require significant investments by firms to develop adequate governance and risk-management

arrangements. In several jurisdictions, these institutions with systemic risk impact are subject to explicit

systemic risk charges, such as additional loss-absorbency capacity, resolution, and crisis management

requirements. Typically, these prudential requirements are applied to the entire group and often extend to

the unregulated activities of the group (such as enterprise-wide approaches to risk management).

Many BigTechs have financial entities that are subject to nonbank financial regulation. For example,

Amazon Pay has a money transmitter license in many US states. However, there are no deposit taking or

insurance activities within the group, which would require groupwide prudential regulation and supervision.

Nonbank or noninsurance regulations are mainly built with activity-based regulations; therefore, BigTechs

can avoid comprehensive groupwide entity-based regulation as long as they can avoid financial activities

that require banking (deposit taking) or insurance underwriting activities. Where rules on some BigTech

activities (such as cloud provision) are enacted, requirements tend to fall on financial institutions that are

already subject to existing regulations. This indirect approach could pose significant challenges on eective

supervision, especially when BigTechs are oering such services cross-border.

Emerging new financial conglomerates created by BigTech could pose additional challenges to financial

regulators. Current regulation and supervision on financial conglomerates are built mainly on sectoral

conduct and prudential rules. While the Joint Forum updated its Principles for the Supervision of Financial

Conglomerates in 2012 to reflect the lessons learned from the 2008 global financial crisis, it did not make

fundamental changes in the recommendations on regulatory architecture for the regulation of financial

conglomerates. Sectoral regulations remain the binding requirements for financial conglomerates, with

an expectation that integration and intragroup transactions are usually limited and so group-specific risks

9

Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendations, which are the international standards on AML/CFT, apply to

institutions that engage in a range of activities, including deposit taking, lending, and money or value transfers. BigTechs

will be captured if they carry out the covered activities. In practice, however, many jurisdictions may not yet subject

BigTechs that engage in the covered activities to AML/CFT obligations due to the rapid evolvement of the sector and the

business model. Such gaps may give rise to regulatory arbitrage.

12 International Monetary Fund—Fintech Notes

would not have systemic implications. However, the new business models of BigTech conglomerates may

change this assumption. Given their size, many products or services have the potential to be systemic at

launch. Furthermore, while in isolation these individual activities might not give rise to systemic risk, when

highly integrated they could create risks not addressed by sectoral regulation, which could result in financial

stability implications in the long term.

Over the longer term, concentration risks need to be considered in the context of BigTech. Existing

regulatory frameworks ultimately could result in concentrated markets, where BigTech firms are able to

outcompete incumbents and start-up entrants. In particular, BigTech conglomerates may provide better or

faster financial services with cross subsidies from their core business in the short term, which would enable

them to increase their market share in multiple financial sectors and create dominating powers in the long

term. While this will bring some benefits to users, market dominance for platform-based business models

could lead to new conduct and market integrity risks, where BigTech might rely on markups rather than inno-

vation to increase revenues, resulting in lower overall innovation and greater costs to end users. Merchant

fees in payment services are one example where increased market power may lead to higher costs that

might then be passed on to end users.

BigTech expansion to the financial services sector might also change the power balance between regula-

tors and regulated firms. In the existing financial ecosystem, systemically important banks have a relatively

influential position in relation to financial regulators (to balance that, supervisors have ample access to the

board and senior management and are able to closely follow and monitor the business). However, even

those big banks’ activities derive implicit benefits from the safety net of central banks, particularly that of

their home jurisdiction. Therefore, while scope for regulatory arbitrage exists (such as on a cross-border

basis), group supervision predicated on global standards (such as Basel III) helps narrow the scope for

arbitrage. BigTech’s expansion will shift the power dynamic toward the operators and technologies from

the regulators (especially host regulators). BigTech is less reliant on regulated financial services since the

revenue from regulated financial services still accounts for a small percentage of its total revenue. Those

firms with platform-based businesses are less exposed to credit and liquidity risks, thus they don’t have

material financial or safety net needs. In addition, due to the global nature of their business, they can more

easily relocate headquarters and main activities abroad.

New conduct risks are arising from BigTech’s predominantly retail-focused business model. BigTech activ-

ities are heavily skewed to retail business, and a number of anticompetitive behaviors have been observed

in their nonfinancial services (such as e-commerce). Market conduct regulation in advanced economies has

comprehensive regulations to address conflict of interests, and so some anticompetitive behaviors might be

prohibited by existing financial regulations. However, conduct regulations may not have been implemented

or strictly enforced in many low-income and emerging markets.

A regulatory framework that favors one type of entity over another will generate unfair outcomes and

create regulatory arbitrages and a distorted market. Policies such as open banking, and more broadly open

finance, have reduced barriers to entry, with the aim of increasing competition in financial services such as

payments. While the implementation of open banking and/or open finance policies diers across jurisdic-

tions, those policies will commonly require banks and regulated firms to share limited data, including certain

account and transaction data, to authorized third-party providers, with the consent of the consumer. In

practice, the requirement means the transfer of data from financial incumbents to new entrants like fintech

start-ups and BigTech. This requirement may have the consequence of reducing competition in the longer

term, creating too-big-to-fail entities and resulting in worse outcomes for consumers, markets, and financial

stability.

In line with the BFA, authorities should adapt regulatory frameworks and supervisory practices for the

orderly development and stability of the financial system. These frameworks can facilitate the safe entry

BigTech in Financial Services: Regulatory Approaches and Architecture

of new products, activities, and intermediaries; sustain trust and confidence; and respond to risks. Some

jurisdictions have created specialized licensing regimes like charter-lite licenses and phased authorization,

which may provide a proportionate and controlled regulatory regimen for fintech start-ups. Other jurisdic-

tions facilitate the entrance of these entities by providing specific licenses for individual activities. Some

approaches waive certain requirements, and others provide flexible interpretation of existing regulations.

The BFA generally supports approaches that embrace the promise of fintech and enable new technologies

to enhance financial service provision while keeping risks in check.

To address the risks from the range of financial services BigTech provides and the growing concerns

about their potential systemic importance, holistic policy responses may be needed. Despite the wide

range of financial activities provided by BigTechs, a lack of groupwide regulation potentially provides these

firms with a competitive advantage—not always through innovation and better products, but through regula-

tory arbitrage. Unlike banks, where ancillary activities might fall under group regulation, the consumer data

consolidated by BigTech, for example, is not usually covered by financial services regulation. This means that

some modification and adaptation of regulatory frameworks may be needed to contain risks of arbitrage,

while recognizing that regulation should remain proportionate to the risks. Holistic policy responses may be

needed at the national level, building on guidance provided by standard-setting bodies.

14 International Monetary Fund—Fintech Notes

IV. Regulating BigTechs—Now and Later

Figure 1. Short, Medium, and Long Term Regulatory Frameworks

Source: IMF Sta.

Existing regulatory frameworks are often fragmented across jurisdictions, which can lead to regulatory

arbitrage, policy gaps, and a buildup of financial stability risks across borders. BigTech operations are cross-

border by nature. The BFA identifies the importance of international regulatory cooperation and information

sharing as a way of mitigating these cross-border risks while reducing regulatory friction for entities to scale

across markets. Sharing experiences and best practices with the private sector and with the public at large

can help to catalyze discussions on the most eective regulatory response to BigTech, considering country

circumstances, and to build a global consensus on the way forward.

The regulatory community is looking to tackle the unique challenges associated with regulating BigTech.

Many of the existing approaches to regulation are relevant and appropriate for BigTech, such as conduct

requirements applicable to securities transactions. The existing approaches of activity-based and entity-

based regulation could be applicable once the regulatory perimeter is expanded to cover BigTech entities

and groups.

Yet these adaptions cannot easily be implemented immediately, leaving a potential gap in regulation. In

the meantime, it would be useful for authorities, with close coordination globally and ideally with support

from the relevant standard-setting bodies, to encourage BigTechs to develop codes of conduct that address

the spillover risks from unregulated activities to the financial sector. While this could create better gover-

nance and oversight across the whole entity and require fewer resources from supervisors, enforcement

and early action involving the unregulated activities of BigTech groups would still be limited. To address

the lack of enforcement and early action by supervisors, BigTechs should be encouraged or required to

enhance disclosure of their financial services to foster market discipline and improve their provision of

financial services.

Greater disclosures can provide more information to markets and consumers to help them make better

informed decisions. However, the current disclosure by BigTechs does not describe their financial services

and associated risks in detail (see Box 2 for more detail). This in turn may trigger an unsustainable shift in

risk from BigTechs to financial institutions which may cause excessive risk taking. Dierent jurisdictions have

dierent approaches to the type and level of disclosures required by entities, and such disclosures can be

mandatory (through regulation) or voluntary (through certain types of codes of conduct or best practice).

They can cover a range of issues, such as dierent activities being carried out by the entity, partnerships with

BigTech in Financial Services: Regulatory Approaches and Architecture

other firms, and risk of activities being provided. While in many jurisdictions such disclosures can be imple-

mented quickly—especially when done voluntarily—they are most impactful where disclosure is mandatory

and the type of disclosure is standardized across firms. In many instances, disclosure can be an eective first

step in leveling the playing field, as long as authorities and market participants are aware of its limitations.

Some jurisdictions use industry codes as an important regulatory tool that can provide some market

protections while saving regulatory resources. Industry codes can assist authorities that have either stretched

resources or limited powers in relation to certain market actors. For example, in securities regulations, many

authorities make active use of self-regulatory organizations, which form an important complement to the

regulator in achieving the regulatory objectives, especially regarding investors’ protection. Such collabora-

tion between the regulators and industries could usefully be applicable to fintech and BigTech regulation.

In fact, in some jurisdictions, industry codes may be recognized by the regulatory authority (such as the

UK FCA and the Monetary Authority of Singapore), providing greater certainty to markets and consumers.

These codes are best developed and implemented when there is public-private collaboration between

BigTech, incumbent financial institutions and authorities allowing areas of mutual concern to be covered,

with public consultation for transparency. Such codes should focus on delivering good outcomes rather

than prescribing detailed rules.

Industry codes may help regulatory authorities improve certain outcomes from BigTech expansion into

financial services. Industry codes can focus on dierent market behaviors of BigTech but could be useful to

limit the spillover risks from unregulated parts of the business. They could be used to prescribe outcomes

regulators would like to achieve (for example, clearer communication, managed risk taking, protecting and

safeguarding consumer funds or data). They are generally quicker to implement than larger scale policy

changes (for example, implementing a home/host regulatory split based on entity- and activities-based

regulation). However, industry codes of conduct are not a perfect substitution for a robust regulatory

framework. Codes may give rise to “halo eects” where users believe entities are regulated and may be

under the false assumption that there are regulatory protections in place. This could lead to reputational risk

for authorities should these entities fail or if certain risks crystalize.

16 International Monetary Fund—Fintech Notes

BOX 2. Disclosure of BigTech Financial Services

BigTech financial services are growing via partnerships with incumbents. As with their nonfinan-

cial services business lines, BigTech firms remain platform-based business models that facilitate

financial transactions between incumbents and end users. Therefore, BigTech firms don’t normally

provide funding or take credit and liquidity risks from the provision of financial services. Funding

and financial risks are usually taken by partnering banks and other financial institutions.

Disclosures by BigTech firms until now have not included critical information on risk sharing

between BigTechs and incumbent financial institutions. Many large BigTech firms are oering

payment services, for example, which could inherit certain credit and liquidity risks of merchants

and the end users, unless those risks are taken or guaranteed by the partnering financial

institutions.

Some BigTech firms are actively providing lending services themselves. BigTech firms that have

grown from e-commerce business often have significant lending activities with their merchants and

buyers. They often disclose these activities under “account receivables” without any information on

credit quality. In one situation, one firm seems to have had extensive credit support from a related-

party bank, but the bank is outside the group consolidation. In general, there is not much disclosure

by the BigTech firms on information and risks of their lending activities.

BigTech financial businesses are exposed to contagion and reputational risks, which should

warrant a more comprehensive disclosure. While BigTechs may not be currently exposed to credit

and liquidity risks related to financial services, end users may be using these services based on their

trust in the service quality and reputation of the BigTech firms. If systematically important BigTechs

collapse, banks that use BigTech platforms or cloud services will face large operational challenges,

which may potentially require exceptional rescue interventions. Currently, because of the lack of

transparency, the costs of this type of disruption are largely unknown. In the scenario where the

partnering financial institution becomes impaired, a BigTech might need to step in and provide

continuity to its financial services by taking on credit and liquidity risks. To help mitigate these risks,

BigTech firms should be required to enhance their disclosure regarding financial services (including

those risks such as step-in and reputational risks, which may be less quantifiable).

IMPLICATIONS FOR REGULATORY ARCHITECTURE

Longer term solutions may require more substantive changes, such as regulators reevaluating their roles as

home and host supervisors. For instance, host jurisdictions may consider activity-based regulations supple-

mented by groupwide supervision tailored to a BigTech’s specific risks. This can be built within existing

regulatory frameworks and can be implemented with fewer additional resources. Supplementary group

supervision can help impose prudential requirements across a BigTech group’s financial activities, but the

eectiveness of such requirements could be limited. Over the longer term, a better solution would be that

home jurisdictions consider entity-based regulation of large tech conglomerates through entirely new regu-

latory frameworks designed specifically to capture the risks of BigTech—for example, a “BigTech license” or

systemic designation for large tech conglomerates that conduct certain activities within financial services.

This approach can capture risks from across financial activities but would likely require significant supervi-

sory resources.

Home supervisors of BigTech groups will need to strengthen coordination eorts with governmental agencies,

other domestic regulators, and host regulators globally. If BigTechs grow to systemic levels, it is more likely that

BigTech in Financial Services: Regulatory Approaches and Architecture

home supervisors will need an entity-based approach. They will need to significantly improve domestic coordi-

nation with relevant authorities (such as data, privacy, competition, and consumer protection agencies). They will

need to work more closely with domestic regulators from other sectors in which BigTech entities are conducting

business. Home regulators will also need to allocate resources into international coordination. A robust regula-

tory architecture (such as clear and eective coordination arrangements among the relevant financial regulators

or integration of regulatory authorities) will help to pool scarce resources for new tasks.

For host supervisors, a suitable regulatory approach will be best determined by the country context. Host

supervisors may potentially rely on home supervisors and focus on activity-based regulations if home super-

visors have implemented robust regulations. However, if actions taken by home supervisors are slower than

BigTech growth in host jurisdictions, host supervisors may need to take more concrete actions. This could

have significant resource implications to the host supervisors, which may require substantial reform of regu-

latory architecture, and smaller jurisdictions might find it more dicult to enforce than larger jurisdictions.

POTENTIAL REGULATORY APPROACHES

Home authorities have several options when implementing an entity-based approach to regulation. Some

home jurisdictions might require BigTechs to create financial holding companies for their financial services

activities, allowing those authorities to supervise the holding companies on an entity basis. Others may

create more general BigTech licenses and regulate not only the financial entities but also the entire group.

Other jurisdictions might decide to designate BigTechs in financial services as systemically important infra-

structures. Current regulatory approaches are summarized in Box 3.

While those options are theoretically appealing, implementation of an entity-based approach is not

straightforward. To implement an entity-based approach, the most important first step is to identify the

lead/home supervisor. However, identifying a suitable nexus for home regulation might not always be easy,

particularly in instances where a BigTech might be headquartered in one jurisdiction, delegate certain key

decision-making functions in another jurisdiction, and carry out most of its financial services activities in a

third jurisdiction. Even with a suitable nexus, dierent jurisdictions might approach entity-based regulation

for BigTechs dierently depending on their legislative frameworks and the nature of BigTech activities.

Financial regulators may not always take the lead in conducting entity-wide regulation for BigTech.

Financial activities of BigTech and their systemic implications may not be the first priorities of BigTech regu-

lation as the biggest concerns would remain fair competition. It is likely that in some jurisdictions, close

collaboration among financial authorities and other domestic authorities will be required given the cross-

sectoral nature of BigTech. In these instances, other authorities, including competition authorities, might

take the lead in ensuring entity-wide oversight of BigTech firms.

When a jurisdiction chooses a designation approach, suitable metrics underpinning the designation

would need to be agreed across borders. Metrics may include the degree of concentration and intercon-

nectedness, market share of their related financial services (including the services provided by partnering

entities), and degree of cross-border and cross-sectoral activities. Such metrics should be developed in

close cooperation with foreign authorities where BigTechs have material financial activities.

An activities-based approach for host authorities can be easier to implement, although there will be

some challenges. While defining relevant activities is likely to be dicult—particularly where these are

either new activities or current activities carried out through new technologies or business models—an

activities-based approach for host jurisdictions might be easier to implement. BigTechs, much as they do

now in many jurisdictions, are likely to need specific licenses or permissions to conduct specific activities

within a jurisdiction. In certain instances, the host jurisdiction may implement or update existing regula-

tion to reflect the growth of BigTechs, for example, by strengthening some operational, cyber, capital, or

liquidity requirements.

18 International Monetary Fund—Fintech Notes

BOX 3. Case Studies of Current Entity- and Activity-Based Regulatory Approaches to

BigTech

Chinese authorities have taken steps toward an entity-based approach through expanding their

regulatory perimeter to bring BigTech conglomerates under their regulation and supervision.

BigTechs in China have grown to account for a significant market share in payment services and were

rapidly increasing their presence in lending and asset management services. To address growing

concerns on systemic risks, Chinese authorities required BigTech entities to set up a financial

holding company where each line of the business (for example, consumer finance and insurance)

will be subject to relevant prudential and governance requirements. However, since many of the

specific requirements for the financial holding companies are yet to be defined, actual impact on the

BigTechs’ business models is yet to be determined.

Chinese authorities have also deployed indirect supervision through existing commercial banks

to align incentives between BigTechs and partnering banks. Regulations require commercial banks

to carry out independent loan risk assessment; to cap co-lending with internet platforms or other

partners at no more than 50 percent of outstanding loans; to limit co-lending with one platform to

25 percent of the bank’s tier-1 net capital; and to conduct online lending only within the jurisdiction

of their registration. Internet platforms are also required to provide at least 30 percent of the funding

in any single joint loan with a bank. Regulations clarify that regional banks would not be able to raise

cross-regional deposits from platforms, leading the platform to remove bank-deposit products.

Those requirements should also help to address excessive interconnectedness and contagion risks

from BigTech financial services to incumbent financial entities.

European authorities are also taking steps to mitigate the risks that arise from BigTech; however,

the focus is on activities-based regulation as a primarily host jurisdiction. The Digital Services Act and

the Digital Markets Act contain targeted powers to leverage against platform providers and online

gatekeepers, which will cover many BigTech entities. An online gatekeeper is an entity that acts as a