O , N -

RESEARCH

RETIREMENT

CAN RETIREES BASE WEALTH

WITHDRAWALS ON THE IRS’

REQUIRED MINIMUM DISTRIBUTIONS?

B W S A W*

* Wei Sun is an assistant professor at the Hanqing Advanced Institute of Economics at Renmin University in Beijing,

China. Anthony Webb is a research economist at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. This brief, which

is adapted from a longer paper (Sun and Webb ), provides general guidance that may be useful in many circumstances.

However, a household’s specific investment or financial planning strategy should be based on its personal circumstances.

The authors strongly recommend that households obtain appropriate financial advice prior to making any decisions.

Introduction

As (k) plans have largely replaced traditional pen-

sions, baby boomers have become the first genera-

tion that must decide how much of their savings to

spend each year in retirement. Boomers must find a

strategy that best balances the risk of outliving their

wealth against the cost of unnecessarily restricting

their consumption.

This brief, which is adapted from a recent paper,

explores the possibility of basing withdrawals on the

Internal Revenue Service’s rules for Required Mini-

mum Distributions (RMD) for (k)s and IRAs. The

analysis compares an RMD strategy with existing

rules of thumb and with a pattern of optimal with-

drawals.

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first

section details the rules of thumb, including the

proposed RMD strategy. The second section defines

an optimal strategy, which serves as a benchmark

for comparing the rules of thumb. The third section

provides the results of this comparison. The fourth

section suggests a way to modify the RMD strategy

to bring it closer to the optimal. The final section

concludes that the RMD strategies oer retirees a

reasonable trade-o of the benefits and risks inherent

in spending down one’s retirement savings.

Rules of Thumb for

Asset Drawdown

People adopt rules of thumb for drawing down their

assets because rules are relatively simple to follow.

This section describes the traditional rules of thumb

and then discusses the potential for an RMD strategy.

Traditional Rules of Thumb

Three traditional rules of thumb include relying on

the investment earnings produced by the assets,

calculating withdrawals based on life expectancy, and

adopting the so-called “-percent rule.”

Spend interest only. Some retirees use the straight-

forward strategy of leaving the principal in their

retirement accounts untouched and spending only

the dividends on stocks and the interest on bonds

or certificates of deposit. This strategy can work for

wealthy individuals, but has serious drawbacks for

people who lack substantial retirement savings. One

disadvantage is that, when they die, they will leave be-

hind all of their initial wealth plus capital gains. This

strategy may be desirable for those who want to leave

a bequest, but in other cases it unnecessarily restricts

retirement consumption.

Center for Retirement Research

Another drawback to the “interest only” strategy

is that a retiree’s income – and consumption – are dic-

tated by his asset allocation. The retiree then runs the

danger that the tail (the desire to consume) may begin

to wag the dog (investments), resulting in a portfolio

allocation that does not minimize the risk for any

given level of expected return on the portfolio. That

is, the retiree may over-invest in dividend-yielding

stocks, losing the benefits of portfolio diversification.

Base withdrawals on life expectancy. A second

draw-down strategy used in retirement is to spend all

financial assets over one’s life expectancy, as predicted

by life tables. The equation for calculating annual

withdrawals under this strategy is:

Annual withdrawal = ___________ x wealth

r

– ( + r)

-t

where r is a risk-free interest rate on the investments

and year t is the remaining life expectancy.

This strategy has two significant drawbacks. First,

the above equation is not a simple calculation for

most people. Second, retirees face a high probability

– a -percent chance – that they will outlive their sav-

ings and be forced to rely solely on Social Security.

Adopt the 4-percent rule. A third strategy is to

spend a fixed percentage of one’s initial retirement

savings. For example, under the so-called -percent

rule advocated by some financial planners, the retiree

each year withdraws percent of that initial balance.

The advantage is that the retiree has a low probability

of running out of money. The downside is that such

a rule does not permit retirees to periodically adjust

consumption in response to investment returns. For

example, if returns are less than expected in a given

year, the retiree should respond by reducing con-

sumption to preserve the assets – a fixed -percent

withdrawal is not consistent with such flexibility.

Required Minimum Distributions

An alternative strategy is to base withdrawals on the

IRS’s Required Minimum Distributions (RMD), a

percent of assets that individuals are required to with-

draw each year starting at age ½.

The IRS makes

no claim that the RMD, which is designed to recoup

deferred taxes, is the basis of an optimal draw-down

strategy. Yet an RMD approach satisfies four impor-

tant tests of a good strategy.

First, like other rules of thumb, it is easy to follow.

The IRS stipulates withdrawal percentages based

on life expectancy tables.

A withdrawal schedule at

younger ages – percent of assets withdrawn, by age

– can be based on the same life tables used for the

RMD rules (see Figure ). Second, the RMD strategy

provides a superior way to manage wealth, because it

allows the percentage of remaining wealth consumed

each year to increase with age, as the retiree’s remain-

ing life expectancy decreases. Third, since consump-

tion is not restricted to income, the household is less

likely to chase dividends and is more likely to have a

balanced portfolio. Fourth, consumption responds

to fluctuations in the market value of the financial

assets, because the dollar amount of the drawdown is

based on the portfolio’s current market value.

F . R M D

P A, A

Source: Authors’ calculations based on IRS tables for Re-

quired Minimum Distributions (see U.S. Department of the

Treasury, ); annual percentages are in the Appendix.

0

4

8

12

16

65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100

To determine which real-world strategy would pro-

duce the best possible outcome, the rules of thumb

can be compared with an optimal wealth draw-down

strategy.

An Optimal Draw-down

Strategy

Managing retirement wealth involves trading o the

enjoyment of spending one’s assets on consumption

against the risk of spending too much and prema-

Issue in Brief

turely depleting one’s resources. The household’s

goal is to optimize this tradeo – in economic jargon,

to maximize the expected utility of consumption.

This analysis uses the example of a married couple

in which the spouses are the same age and both

retire at .

The husband receives Social Security

benefits of $, annually, and the wife receives

$, through a spousal benefit, for a total house-

hold income of $, per year.

Assume that the

household has $, in financial assets, excluding

the equity in their house.

The investment options

include stocks and risk-free bonds.

Each year the

household decides how to allocate its assets between

stocks and bonds and how much to take out of its

account. The model yields a draw-down pattern that

maximizes the expected utility of consumption.

The Horse Race

The next step is to conduct a horse race in which the

benefits generated by the optimal draw-down strategy

are compared with the benefits of the traditional rules

of thumb. This comparison uses a measure called

Strategy Equivalent Wealth (SEW). The number for

each strategy is the factor by which the dollar value of

the household’s wealth, at age , must be multiplied

so that the couple is as well o as a household that

follows the optimal strategy. The optimal strategy has

an SEW of , and the SEWs for the suboptimal strate-

gies are, by definition, greater than .

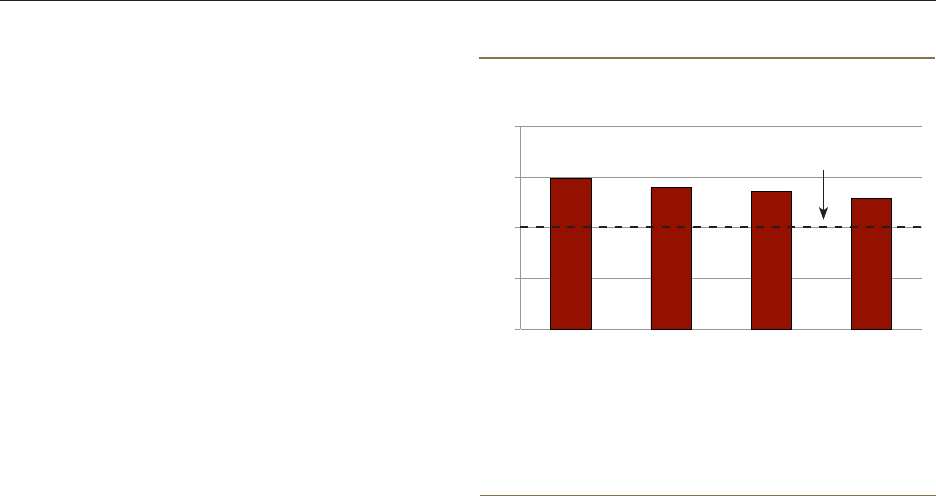

Figure shows the results for the retired couple.

For the rules of thumb, the SEW factors range from

. for the life expectancy strategy – the best – to .

for the -percent rule – the worst. Interestingly, the

RMD approach, with an SEW of ., performs better

than the -percent rule. In dollar terms, the couple

would need about $, more – or percent (.

minus .) of their $, savings – to be persuad-

ed to use the -percent rule instead of the RMD strat-

egy. The RMD approach also has advantages over the

other rule of thumb strategies, as discussed earlier,

that are not captured in the SEW calculations. For

example, the RMD approach is easier to follow than

the life expectancy strategy. And the RMD approach

does not provide a temptation to chase dividends as

does the interest only strategy.

1.49

1.39

1.36

1.29

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

F . D- S, S

E W (SEW)

Source: Webb and Sun ().

-percent rule

Required minimum

distribution

Spend interest,

dividends only

Spend assets over

expected lifetime

Optimal

Making Good Better

A potential criticism of the RMD rule is that it results

in relatively low consumption early in retirement.

While this outcome might be optimal for some

households, particularly those fearful of rising health

care costs, others might prefer greater consumption

at younger ages when they are better able to enjoy it.

This result could be achieved by a modification to the

RMD rule, namely to consume interest and dividends

(but not capital gains), plus the RMD percentage of

financial assets. To illustrate, a -year-old couple

with financial assets of $, who received $,

of interest and dividends in the last year, would spend

$,: the $, in interest and dividends, plus .

percent (the age Annual Withdrawal Percentage

under the RMD strategy) of $,. In contrast, a

household following the unmodified RMD rule would

spend just $,.

Figure on the next page compares the SEW of

the modified RMD strategy with the SEWs of the

strategies reported in Figure . At ., it outper-

forms all the alternatives, including the unmodified

RMD rule. The disadvantage of the modified RMD

rule is its greater complexity. Although (k) and

IRA statements report interest and dividends, house-

holds must extract this information and perform the

Center for Retirement Research

necessary calculations to determine their withdrawal

amount. One solution might be for (k) and IRA

statements to report the amount available for spend-

ing under the modified RMD rule.

1.49

1.39

1.36

1.29

1.03

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

F . D- S I

M RMD, S E W

(SEW)

Source: Webb and Sun ().

-percent rule

Required minimum

distribution

Spend interest,

dividends only

Spend assets over

expected lifetime

Optimal

Modified required

minimum distribution

Conclusion

Rather than attempt the complex calculations neces-

sary to arrive at an optimal strategy for drawing down

and spending their retirement savings, retirees rely

on easy-to-follow rules of thumb such as the -percent

rule advocated by some financial planners. This brief

suggests that the IRS’ Required Minimum Distribu-

tion rules may be a viable alternative. For financial

and practical reasons, the eectiveness of the alterna-

tive RMD strategy compares favorably to traditional

rules of thumb. And a modified RMD strategy does

even better.

Endnotes

Devising a retirement spending and investing plan

requires, among other things, estimating longevity,

trading o spending early in one’s retirement years

against saving money for old age, and choosing how

much to invest in risky stocks, which oer higher

expected returns in exchange for greater risk.

One other solution to the draw-down issue is to

buy an annuity that provides a guaranteed regular

income sucient to meet the household’s essential

expenses, investing any remaining assets. However,

retirees have resisted buying annuities, perhaps out

of a desire to retain liquidity as protection against

unexpected medical costs. Other proposed explana-

tions for the lack of enthusiasm for annuities include

the presence of a bequest motive, unattractive annuity

pricing due to adverse selection, and various behav-

ioral biases. See Brown () for an overview of the

literature.

A Google search for “-percent rule” and “retire-

ment” produced more than , hits. Also see

Bengen ().

Failure to take the Required Minimum Distribu-

tions results in a -percent tax on the required

withdrawal amount.

The IRS’ RMD distribution table reflects estimates

of the joint life expectancy of couples in which the

spouse is years younger than the account holder.

It should be noted that while the IRS requires the

withdrawals, it does not require retirees to spend their

withdrawals.

The paper on which this brief is based also provides

utility functions and comparisons of draw-down

strategies for couples in which the wife is six years

younger, as well as for single men and single women.

If the husband dies, the wife would begin collect-

ing Social Security survivor benefits, which would pay

$, and result in a reduction in total household

income.

Households with fewer financial assets may view

them as a liquidity backstop for emergency expendi-

tures, rather than as an income source. Households

with more financial assets may have bequest require-

ments that are an important consideration in their

decumulation plans.

The assumed real interest rate for the risk-free

bond is percent, which is above current rates but

approximates the long-run average rate.

The utility function is discounted by the couple’s

rate of time preference, assumed to be percent.

The SEW results vary depending on the number

of individuals and on various assumptions. For more

detailed results, see Sun and Webb ().

References

Bengen, William P. . “Determining Withdrawal

Rates Using Historical Data.” Journal of Financial

Planning (): -.

Brown, Jerey. . “Understanding the Role of An-

nuities in Retirement Planning.” In Overcoming

the Saving Slump: How to Increase the Eectiveness

of Financial Education and Saving Programs, edited

by Annamaria Lusardi. Chicago, IL: University of

Chicago Press.

Sun, Wei and Anthony Webb. . “Should House-

holds Base Asset Decumulation Strategies on

Required Minimum Distribution Tables?” Work-

ing Paper -. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for

Retirement Research at Boston College.

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue

Service. . Individual Retirement Arrangements.

Publication . Washington, DC.

Issue in Brief

APPENDIX

A W P

R M D S

Age %

Age

%

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Note: Individuals are required to follow the RMD rules

during the calendar year in which they reach age ½. The

withdrawal schedule for younger ages used in this analysis

is calculated based on the same life tables used for the RMD

rules.

Source: Webb and Sun ().

Issue in Brief

About the Center

The Center for Retirement Research at Boston

College was established in through a grant

from the Social Security Administration. The

Center’s mission is to produce first-class research

and educational tools and forge a strong link between

the academic community and decision-makers in

the public and private sectors around an issue of

critical importance to the nation’s future. To achieve

this mission, the Center sponsors a wide variety of

research projects, transmits new findings to a broad

audience, trains new scholars, and broadens access to

valuable data sources. Since its inception, the Center

has established a reputation as an authoritative source

of information on all major aspects of the retirement

income debate.

Aliated Institutions

The Brookings Institution

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Syracuse University

Urban Institute

Contact Information

Center for Retirement Research

Boston College

Hovey House

Commonwealth Avenue

Chestnut Hill, MA -

Phone: () -

Fax: () -

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: http://crr.bc.edu

© , by Trustees of Boston College, Center for Retire-

ment Research. All rights reserved. Short sections of text,

not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without ex-

plicit permission provided that the authors are identified and

full credit, including copyright notice, is given to Trustees of

Boston College, Center for Retirement Research.

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to

a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA)

funded as part of the Financial Literacy Research Consor-

tium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely

those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or

policy of SSA, any agency of the federal government, or the

Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

RESEARCH

RETIREMENT