1

Penning- och valutaPolitik 2018:2

Sweden’s scal framework and monetary policy

Eric M. Leeper*

The author is Professor of Economics at the University of Virginia

Basic economic reasoning tells us that monetary and scal policies always

interact to jointly determine aggregate demand and the overall level of

prices in the economy. This arcle interprets Sweden’s explicit monetary and

scal frameworks in light of this reasoning, bringing recent Swedish inaon

and interest-rate developments to bear on the interpretaons. Theory and

evidence raise the queson of whether the two policy frameworks are mutually

consistent.

1 Introducon

Basic economic reasoning tells us that monetary and scal policies necessarily interact

in the short, medium, and long runs. These interacons jointly determine an economy’s

macroeconomic developments. This reasoning is completely general, independent of any

parcular economic model or view of how the economy operates.

Most countries’ monetary and scal policy instuons, in contrast, are founded on the

presumpon that the two policies can and should operate independently of each other. This

presumpon underlies the creaon of central banks that are given well-specied mandates

to control inaon and stabilize the real economy and to operate in isolaon from pressures

that might emanate from scal authories. Fiscal policy, meanwhile, is assigned the task of

stabilizing debt – what is called ‘sustainable scal policy’ – and oen lile else. Underlying

this instuonal construct are the beliefs that

(i) scal policy has lile, if any, impact on inaon;

(ii) monetary policy has negligible scal consequences;

(iii) the single-minded scal pursuit of debt stabilizaon supports, rather than thwarts,

the central bank’s mandates.

Somemes, this instuonal arrangement works. At other mes, the arrangement leads to

monetary and scal policies that are mutually inconsistent.

The presumpon that policies can and should operate independently denies an essenal

fact about modern public nance: governments issue nominal bonds – bonds denominated

in local currency – but bondholders care about the real value of those bonds. The real value

comes from deang nominal debt by the overall level of prices in the economy, something

like the consumer price index. Because modern central banks aim to target the rate of

change of the price level – the inaon rate – it is impossible to separate monetary and scal

policy completely. And eorts to do so can create policy conicts.

Recent Swedish monetary and scal acons illustrate the possibility of conict. At

a me when monetary policy has been aggressively expansionary in an eort to raise

inaon – negave policy interest rates for three years, coupled with signicant asset

purchases that have produced a more than four-fold increase in the central bank’s balance

sheet from 2007 to 2017

1

– scal policy has become more contraconary, with net lending

1 Total assets more than tripled between the third quarter of 2008 and the rst quarter of 2009 and remained elevated unl

the second half of 2010. Assets have nearly doubled over the negave policy rate period beginning in 2015.

* I thank Campbell Leith and Todd B. Walker for discussions and the Swedish Fiscal Council, Rachel Lee, and Jesper Lindé for

detailed comments. I also thank Hannes Jägerstedt for paently gathering data and explaining them to me. The opinions expressed

in this arcle are the sole responsibility of the author. They should not be interpreted as reecng the views of Sveriges Riksbank.

Sweden’S fiScal framework and monetary policy

2

moving from −1.6 percent of GDP in 2014 to 1.2 percent in the rst two quarters of 2017.

Fiscal policy has been deaonary when monetary policy has been inaonary.

Sweden is a fascinang case to study how monetary and scal policies interact to

inuence the aggregate economy. The country stands out for being explicit about the

objecves and targets of its macroeconomic policies. Sveriges Riksbank, Sweden’s central

bank, exibly targets inaon at two percent, while the government currently pursues a

medium-term net-lending target of 1 percent of GDP. Explicitness makes Swedish policy

behavior amenable to assessment, which is one goal of this arcle. I raise the possibility that

the policy rule that Swedish scal authories follow, parcularly in recent years, may be at

odds with the Riksbank’s primary goal of targeng inaon.

1.1 Targets vs. rules

Explicit policy targets are not sucient to ensure eecve policy performance. Central

banks with explicit inaon targets communicate much more than their target to the public.

There are innitely many ways that the Riksbank could try to achieve its two percent target.

Each way – or ‘policy rule’ – aects private-sector expectaons dierently. Each rule and its

associated expectaons has unique impacts on the public’s economic decisions. To reduce

the likelihood of mistaken public expectaons, the Riksbank communicates the parcular

rule that it tries to follow.

Communicang the rule is challenging. To achieve its inaon target, the Riksbank

analyses a vast array of data – domesc and foreign inaon and real economic

developments and forecasts, current and prospecve values of the krona, public and

nancial market expectaons of inaon, and even polical events at home and abroad.

2

By

describing how these facts and conjectures inuence its choice of the path for the repo rate,

the Riksbank is explaining its policy rule: how the central bank reacts to various kinds of news

that aect Swedish inaon and real acvity. Of course, the Riksbank, and no central bank,

follows a simple algebraic rule that can be precisely and succinctly communicated. But it

does respond systemacally to economic condions and that systemac behavior guides the

public’s formaon of expectaons about future monetary policy acons.

The Swedish government’s net-lending target, while commendable from the viewpoint

of scal sustainability, does nothing to communicate the scal behavior that tries to achieve

the target. Dierent governments are free to choose exactly how and when to hit the target;

the same government can choose dierent methods for achieving the target at dierent

points in me. This is a potenally serious shortcoming of Sweden’s scal framework, a

shortcoming shared by governments the world over. Governments can perhaps be forgiven

for confounding rules and targets. Even the Internaonal Monetary Fund uses the term ‘rule’

to describe scal targets and restraints, rather than to characterize how the scal authority

behaves.

3

Because this arcle focuses on how interacons among scal, monetary, and public

behavior determine the economy-wide price level, to avoid confusion I will delineate

between targets and rules. Targets refer to inaon at two percent and net lending at

one percent, while rules describe the policy behavior that achieves those targets. A rule

characterizes how the choice of a policy instrument – the repo rate, tax rates, expenditure

components – depends on prevailing economic condions. I argue that the policy rules are

all-important for determining the price level and, by extension, the performance of the

macro economy.

2 See Sveriges Riksbank (2018, chapter 1) for examples.

3 Schaechter et al. (2012).

3

Penning- och valutaPolitik 2018:2

1.2 Sketch of arcle

Before geng into details about Sweden, it is necessary to lay some groundwork for

understanding how and why it is essenal to study monetary and scal policies together,

rather than separately. To that end, I describe the nature of policy interacons in any well-

funconing equilibrium. Fundamental economic principles carry some crical implicaons

that conict with beliefs (i)–(iii). First, it is the joint monetary-scal policy regime that

determines an economy’s inaon rate. Second, monetary policy acons always have scal

consequences – consequences that may be large at mes – and how scal policy reacts to

those consequences maers for the ulmate impacts of the monetary policy acons. Finally,

the rule that the government implements to pursue debt stabilizaon maers for the central

bank’s ability to achieve its mandates.

With that economic background in place, the arcle turns to analyse features of Swedish

macroeconomic policies and recent Swedish economic developments. These include

1. negave bond yields over the maturity structure, which constute prima facie

evidence of a scal policy that reduces social welfare, but also reect the low-interest

rate environment in which the Swedish economy nds itself;

2. the fragility – in the sense of potenally inducing instability in government debt – of

Sweden’s net-lending target, for reasons rst arculated by Phillips (1954);

3. evidence of Swedish scal policy behavior and the backing that it provides for

monetary policy;

4. an explanaon of how, parcularly in low-inaon periods, monetary policy acons

can generate potenally substanal scal impacts in subtle ways that are not part of

typical economic analyses at central banks and ministries of nance.

The arcle’s aim is not to cricize Swedish policies. Sweden’s scal situaon is sound:

the government owns equies and its net nancial posion is posive. But the Swedish

government nonetheless issues krona-denominated debt, so the analysis in this arcle

applies to Sweden, as it would to less scally sound economies. The arcle tries to shed light

on how monetary and scal policies in Sweden jointly determine macroeconomic outcomes.

Along the way, the arcle points toward alternave scal rules that are consistent with the

aims of Sweden’s Fiscal Policy Framework and are more compable with the job that the

Riksbank has been tasked to perform.

2 Monetary and scal policy basics

Much discourse about macroeconomic policies applies the following logic. The central bank

sets its policy instruments – a short-term nominal interest rate, the level of bank reserves,

the size and composion of its balance sheet – but does not set taxes and government

expenditures. The government chooses the level and composion of various taxes and

expenditures and the quanty and maturity structure of the debt it issues, but not the

variables the central bank controls. Having established who controls what, analyses of policy

impacts oen proceed along similar lines to ask: How do changes in the central bank’s

(government’s) instruments aect the economy, holding xed scal (monetary) instruments?

Although such quesons seem to make sense on the surface, basic economic reasoning

tells us that it is rarely possible to change a monetary (scal) instrument without eventually

changing scal (monetary) instruments in parcular ways.

Research over the past 25 years establishes this reasoning to emphasize that monetary

and scal policy jointly determine the economy-wide level of prices and the rate of inaon.

4

4 Early contributors include Leeper (1991), Sims (1994), Woodford (1995), and Cochrane (1999). Leeper and Walker (2013)

and Leeper and Leith (2017) are recent overviews. Leeper (2016) explains why central banks – even when they are polically and

operaonally independent – need to pay aenon to scal behavior.

Sweden’S fiScal framework and monetary policy

4

Out of that literature has emerged the understanding that two disnct combinaons of

monetary and scal policy behavior – policy regimes – can determine the price level and

stabilize the level of government debt.

2.1 Policy regimes

Table 1 summarizes the policy mixes that determine inaon and stabilize debt. To make

the arguments clear, I make stark and unrealisc assumpons about policy behavior. The

arguments go through with more plausible assumpons.

The rst regime reects the convenonal view that monetary policy acvely adjusts

the policy interest rate to lean against inaon, while scal policy passively adjusts

primary budget surpluses – revenues less expenditures, not including interest payments

on government debt – to stabilize the long-run debt-GDP rao. This is somemes called

‘monetary dominance.’ Taylor’s famous rule

5

falls into this regime: the central bank raises

the policy interest rate more than one-for-one with the inaon rate and raises the interest

rate more modestly when the output gap increases.

6

Because monetary policy focuses on

stabilizing inaon and the real economy, scal policy must ensure that government debt

remains well behaved. When scal policy makes taxes rise with the level of real government

debt – nominal debt deated by the price level – by more than enough to cover interest

payments and some of the principal, the debt-GDP rao will be stable in the long run.

Many economists believe this regime prevails during ‘normal’ economic mes. All inaon-

targeng central banks believe they operate in this regime.

Table 1. Monetary-scal policy mixes

Policy authority Monetary-scal policy regimes that determine inaon and stabilize debt

Monetary rule

Fiscal rule

Conventional view

Aggressively raises interest rate with inaon

Raises primary surplus with real debt

Alternave view

Weakly raises interest rate with inaon

Pursues other objecves besides debt

stabilizaon

Label ‘Acve monetary passive scal policies’

or ‘Monetary dominance’

‘Passive monetary acve scal policies’

or ‘Fiscal dominance’

A second, alternave, regime can also determine inaon and stabilize debt. In this regime,

scal policy pursues other objecves, such as countercyclical policies or redistribuon of

income, by seng primary surpluses – dened as tax revenues less expenditures, excluding

interest payments on outstanding debt – independently of debt and the price level.

Monetary policy chooses the interest rate so that it responds only weakly – or not at all – to

inaon, which permits expansions in government debt to raise the price level. Higher price

levels and lower bond prices reduce the real market value of debt – the quanty of goods

and services that a government bond can purchase – to make the debt-GDP rao stable.

Some economists call this regime ‘scal dominance.’

At a general level, there is nothing ‘good’ or ‘bad’ about the two policy regimes. Recent

research on jointly opmal monetary and scal policies nds that the best mix of policies in

terms of social welfare has elements of both the convenonal and the alternave views.

7

Both regimes deliver the broad macroeconomic policy goals of determining inaon and

stabilizing government debt. But because monetary and scal acons have dierent impacts

in the two regimes, it is essenal for policymakers to know in which regime the economy

resides.

5 Taylor (1993).

6 For reasons rst arculated by Obseld and Rogo (1983), monetary policy cannot deliver a unique inaon rate in a pure at

currency regime. Cochrane (2011) and Sims (2013) recently emphasized that the Taylor rule permits explosive inaon paths to

be equilibria, along with the stable inaon outcome that economists usually focus on.

7 Sims (2013) and Leeper and Zhou (2013).

5

Penning- och valutaPolitik 2018:2

Because U.S. monetary policy behavior was been widely studied, I will point out several

instances since America le the gold standard in April 1933 in which the Federal Reserve

seems to have followed this alternave behavior: from April 1933 unl about 1936;

throughout World War II unl the Treasury-Fed Accord in March 1951; much of the 1970s;

the 2008 nancial crisis and its aermath.

8

And there have been mes when scal policy

pays scant aenon to debt in order to pursue other objecves: despite extremely high

war debt, in 1948 Congress overrode President Truman’s veto and cut taxes; the Economic

Recovery Plan of 1981 increased primary decits even as the debt-GDP rao was rising from

its post-war low in the early 1980s; both the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliaon

Act of 2001 and the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliaon Act of 2003 cut taxes at mes

of rising debt; the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 increased spending and

cut some taxes despite rising debt; even with record peaceme government debt levels, in

December 2017 the U.S. government passed a major cut in taxes.

9

During and since the nancial crisis of 2007, central banks around the world have

maintained policy interest rates that are pegged at extraordinarily low levels with the aim of

smulang real economic acvity. This behavior places monetary policy into the ‘alternave

view’ category. At the same me, scal policies – parcularly in Europe – have been adjusng

to stabilize government debt following brief excursions into smulave stances designed to

help li economies out of recession. By Table 1’s categorizaons, the mix of pegged interest

rates and stabilizing scal policy, if people expect it would last forever, does not deliver an

equilibrium in which inaon is determined.

10

2.2 Fiscal consequences of monetary policy

To keep this discussion focused, in what follows I consider only the convenonal mix of

monetary and scal policy behavior. That policy combinaon underlies the Riksbank’s

percepons of its behavior and the raonale for Sweden’s Fiscal Policy Framework. The

independent Riksbank pursues its inaon target, while the government acts to ensure debt

is stable. This convenonal view of macroeconomic policies is the foundaon of monetary

and scal instuons in nearly all countries.

My key message is: under this convenonal policy mix, monetary and scal policies

must interact in certain well-specied ways. It is not possible for monetary and scal policy

to operate independently of each other and sll deliver good economic performance.

Understanding the nature of these interacons is essenal to formulang eecve policy

rules.

Monetary policy acons always have scal consequences.

11

Let’s start with something

roune: the Riksbank lowers the repo rate in order to raise inaon. This isn’t the end of the

story: a lower repo rate tends to lower all interest rates, including those on government debt,

so interest payments on outstanding debt decline.

Now scal policy comes into play. Those lower interest payments reduce scal needs.

To ensure that government debt is stable, taxes must be lower or expenditures must be

higher in the future to oset the reduced debt service. Without these scal adjustments,

government debt would steadily fall, eventually making the government a net lender to the

private sector.

But there is actually more to the scal response than simply stabilizing debt. Lower

interest payments on government bonds reduce the wealth of holders of those bonds. If

8 See Taylor (1999), Clarida et al. (2000), Lubik and Schoreide (2004), and Davig and Leeper (2006, 2011).

9 See Davig and Leeper (2006), Bhaarai et al. (2016), and Bianchi and Ilut (2017).

10 This is called ’price-level indeterminacy,’ and is a topic that has received a great deal of aenon in the academic literature.

Indeterminacy means that the inaon rate is not pinned down by policy and is subject to potenally volale uctuaons that

arise from self-fullling expectaons of inaon by the private sector. Woodford (2003) explains that determinacy is a minimal

requirement for opmal policy.

11 Tobin (1980) and Wallace (1981) make this point.

Sweden’S fiScal framework and monetary policy

6

those lower interest receipts do not trigger an expectaon of eventually lower taxes to

compensate for the reduced wealth, lower wealth will lead to reduced demand for goods

and services – lower aggregate demand – and a lower price level.

Because the Riksbank inially reduced the repo rate in the hope of raising aggregate

demand and inaon, the negave wealth eect can thwart the Riksbank’s eorts. To

support monetary policy, scal policy needs to provide scal backing that adjusts future

taxes in the opposite direcon to price-level movements. A higher price level – the Riksbank’s

immediate goal – requires a scal rule that lowers future taxes, while a lower price level

calls for a policy that raises taxes. Such a rule eliminates the wealth eects of central bank

changes in interest rates to deliver the desired eect of monetary policy on aggregate

demand.

The scal rule under the convenonal view in Table 1 both stabilizes debt and provides

the necessary scal backing for monetary policy. A rule that raises future surpluses whenever

real debt increases has two components to it. First, for a xed price level, higher nominal

debt brings forth higher surpluses to ensure government debt is stable. Second, for a xed

level of nominal debt, a lower price level creates the expectaon of higher future taxes to

provide the scal backing for monetary policy’s inaon-targeng acons. The passive policy

rule in the table happens to deliver both desirable outcomes.

The message is: to successfully raise inaon, the Riksbank’s looser monetary policy

(lower repo rate) necessarily requires looser scal policy (smaller budget surpluses) at some

point. That scal response is essenal for the Riksbank to be able to control inaon and

fulll the price-stability policy mission that the Riksdag set out for the bank in the Sveriges

Riksbank Act.

Unfortunately, not all scal rules both stabilize debt and back monetary policy. This is

why it’s important for governments to move beyond adopng targets, toward describing

the behavior that achieves the targets. Both outcomes rely on scal expectaons. If markets

know that higher real debt eventually leads to higher stabilizing surpluses, then scal policy

will not run into sustainability problems, as investors are assured the government will fulll

its nancial commitments. This argument gures prominently in the Swedish scal policy

framework.

12

If bondholders know that lower taxes are sure to follow lower interest receipts,

then monetary policy’s adverse wealth eects will not arise, and interest-rate policy will

aect inaon as intended. This point is missing from the Swedish scal framework.

Appropriate scal backing for monetary policy is crical for the Riksbank to achieve price

stability. By giving the Riksbank the task of targeng inaon, Sweden has chosen an acve

monetary policy, which places Swedish macroeconomic policies in the monetary dominance

regime in Table 1. To be consistent with this monetary policy behavior, it is essenal that

the scal rules used to implement the target provide appropriate backing for monetary

policy. This calls for passive scal behavior. A correctly designed scal rule anchors people’s

expectaons on the belief that scal policy will, in me, react appropriately to monetary

policy by eliminang the wealth eects that monetary policy produces.

12 Swedish Government (2011), pages 5, 7, and 12, for example.

7

Penning- och valutaPolitik 2018:2

3 Internaonal examples

To gain a deeper understanding of the monetary-scal combinaons in Table 1, it is helpful to

consider actual instances when policy behavior departed from the convenonal monetary-

scal regime.

3.1 An important American case

Recovery from the Great Depression illustrates that the alternave monetary-scal policy

mix – scal dominance – has been an explicit policy choice.

13

President Franklin D. Roosevelt

took oce in March 1933 at the lowest point of the Great Depression. Compared to the third

quarter of 1929, real GNP was 36 percent lower, industrial producon had been cut in half,

unemployment rose from almost nothing to a quarter of the workforce, and the price level

had fallen 27 percent. The new president commied to raise the price level by achieving

‘…the kind of a dollar which a generaon hence will have the same purchasing power and

debt-paying power as the dollar we hope to aain in the near future’.

14

The rst step toward

permanently raising the price level was to abandon the gold standard in favor of what

Roosevelt called a ‘managed currency’.

15

Abandoning converbility of the dollar to gold included abrogang the gold clause, a

contractual provision that gave creditors the opon to receive payment in gold, on all future

and past public and private contracts. This changed the nature of government debt. Under

converbility, even though government bonds paid in dollars, the Treasury was required

to convert those dollars into gold on demand. When the Treasury didn’t have the gold on

hand, it had to acquire the gold, typically through higher taxes. The new ‘managed currency’

standard broke the automac link between new bonds and future surpluses: government

bonds were simply promises to pay dollars, which the U.S. government could freely create

without adjusng taxes.

16

Roosevelt used three strategies to convince the public that higher government debt

would not necessitate higher future taxes. First, he made policy depend on the state of

the economy, saying he would run bond-nanced decits unl the economy recovered.

Second, he emphasized the temporary nature of the policy by disnguishing between the

‘regular budget,’ which he balanced, and the ‘emergency budget,’ whose decits were

driven by spending designed to provide relief to those the depression had harmed. Finally,

Roosevelt raised the polical stakes by pitching economic recovery as a ‘war for the survival

of democracy’.

17

The strategies appeared to work because expected inaon began to rise by

spring 1933.

18

Monetary policy behaved passively through the recovery. Aer the United States le

gold, the Fed no longer needed to keep interest rates high to staunch the oulow of gold

and the New York Fed reduced its discount rate to 1.5 percent in February 1934, where it

remained unl August 1937, when it was lowered to 1 percent. One contemporary observer

wrote that the Federal Reserve ‘served merely as a technical instrument for eecng the

Treasury’s policies’.

19

Clearly, the Fed did not follow anything resembling a Taylor rule;

instead, monetary policy permied the expansion in government debt to smulate the

economy, as it does in the alternave policy mix.

Economic recovery was rapid. Real GNP returned to its pre-depression level in 1937. Price

levels – consumer and wholesale price indexes and the GNP deator – rose. The deator

regained its 1920s levels, while the other two fell somewhat short.

13 This draws on Jacobson et al. (2017).

14 Roosevelt (1933b).

15 Roosevelt (1933a).

16 Today all but the 10 percent of Treasury debt that is indexed to inaon is also merely a promise to pay future dollars.

17 Roosevelt (1936).

18 Jalil and Rua (2017).

19 Johnson (1939, p. 211).

Sweden’S fiScal framework and monetary policy

8

Historians like Friedman and Schwartz (1963) and Romer (1992) aribute recovery to

higher growth in the supply of money. Aer America le the gold standard, the Treasury

bought the gold that owed into the country from a polically unstable Europe and paid for

that gold by directly expanding bank reserves and high-powered money. But that explanaon

overlooks the signicant expansion in government debt that took place. The dollar value of

federal debt outstanding doubled in the six years aer leaving the gold standard, reecng

the substanal scal smulus associated with Roosevelt’s relief programs.

Remarkably, this expansion in nominal debt did not raise the debt-GNP rao. Figure 1

plots the par and market values of gross federal debt as percentages of GNP from 1920 to

1940.

20

The vercal line marks departure from gold in April 1933. Aer booming out in

September 1929 at 15.6 percent, the debt-GNP rao rose steadily while the United States

was sll on gold, reaching 44.7 percent in March 1933. It then remained below 45 percent

through the end of 1937. Economic recovery raised both the price level and the real level of

economic acvity, ensuring that the debt-GNP rao was stable.

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

1920 1922 1924 1926 1928 1930 1932 1934 1936 1938 1940

Figure 1. Par and market value of gross federal debt as a percentage

of GNP

Par value Market value

Note. Vercal line marks departure from the gold standard.

Sources: Hall and Sargent (2015), Balke and Gordon (1986), and authors’

calculaons

In this alternave policy mix, the Federal Reserve behaved passively, perming the scal

expansion to raise aggregate demand and with it, prices and output. With this policy mix,

there need not be any conict between scal expansion and scal sustainability because, as

the data in Figure 1 neatly illustrate, the scal expansion did not increase debt relave to the

size of the economy.

21

3.2 Recent internaonal cases

3.2.1 Brazil

Countries have not always provided appropriate scal backing.

22

In recent years, Brazil

followed a scal policy that was unresponsive to debt, while its central bank sought to

target inaon. The 1988 constuon indexed government benets to inaon, which

placed 90 percent of expenditures out of legislave control. At the same me, tax increases

were polically infeasible, leading to growing primary decits with no prospect of reversal.

When inaon began to rise, the central bank aggressively raised interest rates, just as the

20 Par value is the face value of outstanding government debt and is the most commonly cited measure of debt. Market value

incorporates current bond prices, which may change over me to aect the value of debt.

21 The Great Depression was not the only instance of this policy mix. See Davig and Leeper (2006), Erceg and Lindé (2014), and

Leeper et al. (2017) for further examples.

22 Leeper (2017) discusses these and other examples in detail.

9

Penning- och valutaPolitik 2018:2

Taylor principle instructs. Debt service rose, driving up aggregate demand and inaon. In

December 2015, the primary decit was 1.88 percent of GDP, but the gross decit – primary

plus interest payments – was 10.34 percent of output. Figure 2 plots Banco Central do Brasil’s

policy rate, the Selic, along with the consumer price inaon rate from 2013 through 2015.

Despite a doubling of the policy rate, the inaon rate rose by nearly 5 percentage points:

monetary policy does not appear to be controlling inaon. In fact, inaon began to retreat

in 2016 only aer the central bank had stabilized the Selic at 14.25 percent for a year.

3

6

9

12

15

Jan 2013 Jul 2013 Jan 2014 Jul 2014 Jan 2015 Jul 2015 Jan 2016

Figure 2. Brazilian monetary policy interest rate and consumer price

inflaon rate

Policy interest rate (Selic) Consumer price inflaon

Source: IHS Global Insight

It is tempng to infer that Brazil’s problems stemmed from dysfunconal scal policy.

Surely, if scal policy follows well-specied guidelines that ensure ‘responsible’ scal

behavior, monetary policy will be able to control inaon. In fact, the explanaon lies in an

incompable combinaon of monetary and scal policies that were both acve, in Table 1’s

nomenclature.

3.2.2 Switzerland

Switzerland has had ‘responsible’ scal targets for 15 years and it takes those targets

seriously. By ‘seriously’ I mean the government actually achieves those targets.

23

Since a

naonwide referendum in 2001, Switzerland has pursued a debt brake, which limits spending

to average revenue growth over several years. If spending diers from this limit, the

dierence is debited or credited to an adjustment account that has to be corrected in coming

years. Debt brakes have a built-in error-correcon mechanism intended to restrict the size of

government debt.

24

23 This draws on Leeper (2016) and Bai and Leeper (2017).

24 See Danninger (2002) and Bodmer (2006) for addional details and analyses.

Sweden’S fiScal framework and monetary policy

10

-2

0

2

4

30

40

50

60

Figure 3. Debt-GDP rao and CPI inflaon rate in Switzerland

Consumer price inflaon

Government debt (percent of GDP)

Inflaon target

Source: Swiss Naonal Bank

201620142012201020082006200420022000

201620142012201020082006200420022000

The top panel of Figure 3 suggests that Swiss scal targets have worked to limit debt growth.

Government debt has steadily fallen over the past 15 years and now is about 35 percent of

GDP. Remarkably – and Switzerland, along with Sweden, may be the sole excepons – debt

either connued to fall or remained at during the nancial crisis. This stunning outcome is a

testament to the eecveness of scal targets that are reached.

But this prudent scal policy may have come at a cost in terms of inaon targeng.

Switzerland has a two percent inaon target that has been missed chronically. In

Switzerland, inaon has been persistently below target since the beginning of 2009. Low

inaon rates do not seem to be the result of inadequate eorts by monetary policy: policy

interest rates have been negave since the beginning of 2015.

The Swiss case illustrates that scal backing for monetary policy must be symmetric.

When monetary policy reduces (raises) interest rates and interest payments on government

debt, scal policy needs to reduce (raise) taxes. Fiscal rules designed primarily to reduce

government debt may interfere with the symmetry of scal backing.

3.2.3 Japan

Japan is a spectacular case: despite rapidly expanding government debt, the country has

been saddled for decades with extraordinarily low inaon rates. Surely this combinaon

of outcomes undermines the argument that government debt has an impact on inaon.

Sims (2014, 2016) argues that ‘scal pessimism’ in the United States, Europe, and Japan has

made monetary policy ineecve in bringing inaon up to target. He applies this argument

to aging populaons in those economies, who are aware that painful scal adjustments

lie in the not-too-distant future in order to maintain sustainable policies. This means that

when people’s holdings of government debt increase, scal policy adjusts passively to make

people feel less wealthy. Combined with a passive monetary policy that xes the interest rate

indenitely near its lower bound, passive scal behavior makes inaon indeterminate, but

with a downward dri. This is the low-inaon trap that Benhabib et al. (2002) model.

Although inaon in the United States appears now to be approaching its target level

of two percent, in both Europe and Japan it remains stubbornly low despite aggressive

expansionary monetary policy acons. Figure 4 shows that despite some inconsistency in

the 1990s and the period before the global nancial crisis, the Bank of Japan has maintained

a very low policy interest rate, which has now been negave since early 2016. The rapid

increase in base money that started in 2012 reects the Bank’s aggressive government-bond

buying operaons.

11

Penning- och valutaPolitik 2018:2

-0.1

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

Figure 4. Bank of Japan’s call money rate and monetary base in logs

Bank of Japan call rate (le scale) Log of monetary base (right scale)

Source: Bank of Japan

12.0

12.5

13.0

13.5

14.0

14.5

15.0

15.5

Along with aggressive monetary expansion, Japanese governments have run chronic scal

decits that have driven Japanese government debt to unprecedented levels, as Figure 5

shows. How can the combinaon of easy monetary policy and growing government debt as a

share of the economy be reconciled with persistently low inaon?

The answer lies in recognizing that debt can grow as a share of the economy only if

bondholders ancipate higher primary surpluses in the future. Debt’s value can rise only if its

backing rises commensurately. Figure 1 showed that despite sizable scal decits, the debt-

output rao in the United States was stable in the 1930s. This is evidence that bondholders at

the me did not expect expansions of nominal debt to generate larger future surpluses.

0

30

60

90

120

150

180

210

240

1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

Figure 5. Net and gross general Japanese government debt as

percentages of GDP

Net government debt (% GDP) Gross government debt (% GDP)

Sources: Internaonal Monetary Fund and World Economic Outlook

Do Japanese cizens, who hold the bulk of Japanese government bonds, have reason to be

scally pessimisc, in Sims’s terminology? Figure 6 provides some reason for such pessimism.

That gure plots consumer price inaon, with vercal lines marking instances when the

Japanese government raised the consumpon tax in response to fears of scal sustainability.

25

A sharp decline in inaon follows each tax rate hike. Although Prime Minister Abe has

delayed the planned rate rise to 10 percent unl October 2019, there is lile doubt among

Japanese cizens that higher taxes lie in their futures. The IMF’s Arcle IV consultaon

buresses that belief. Among other urgent calls, the consultaon states: ‘Replacing the

25 As an aside, the 10-year yield on government bonds in Japan has fallen steadily since 1990, from a peak of about eight percent

to negave values in 2016. The yield is now about 0.10 percent. Financial markets do not seem to fear scal sustainability.

Sweden’S fiScal framework and monetary policy

12

planned 2 percentage point consumpon tax hike in 2019 with a path of gradual increases of

about 0.5–1 percentage points over regular intervals unl the rate reaches at least 15 percent

will beer balance growth and scal sustainability objecves’.

26

IMF pressure is unlikely to

relax as long as Japanese government debt remains at elevated levels.

Systemac increases in tax rates back higher government debt levels and place scal policy

in the passive regime. This is why Japanese debt expansions are not inaonary and may

explain why the Bank of Japan’s monetary expansions have been ineecve in permanently

raising inaon.

These internaonal examples oer evidence of how monetary and scal policies that

are inconsistent with each other can produce undesirable economic outcomes. Of course,

many other factors also aect Brazilian, Swiss, and Japanese data, so this evidence is merely

suggesve. The rst two are cases in which monetary and scal authories independently

pursue their objecves and scal authories fail to provide the scal backing needed for

the central banks to control inaon. Japan is a situaon in which the inaonary potenal

of monetary and scal expansions is thwarted by scal responses that eliminate the wealth

eects of government debt.

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

Figure 6. Consumer price inflaon in Japan

Note. Vercal lines mark increases in the consumpon tax rate. Solid line is

consumer price inflaon on all items.

Sources: OECD.Stat and Nippon.com

Cons

tax

= 5%

Cons

tax

= 3%

Cons

tax

= 8%

Cons

tax

= 4%

4 Negave nominal bond yields

Like several other European countries, Sweden has been going through the unusual situaon

in which nominal government bond yields have been negave, even at horizons as long as

ve years. While there are many reasons that nominal yields have turned negave – economic

weakness in the wake of the global nancial crisis, aging populaons, and so forth – monetary

policy behavior is certainly a major factor. Lower monetary policy interest rates tend to reduce

interest rates across the maturity spectrum.

Persistently negave real government bond yields may be prima facie evidence that scal

policy could be improved. Essenally, the private sector is telling the government that it is

willing to pay for the right to lend to the government. When real yields remain negave, it

must mean that the government is not taking the private sector up on its generous oer.

Medium-term government bond yields are negave because demand for those safe assets

is very strong. Strong demand bids up bond prices at the relevant maturies, driving down

yields. If the government were to respond to the strong demand by increasing supply of the

desirable assets, yields would rise. Negave yields, therefore, may reect a ‘shortage’ of high-

demand assets.

27

26 Internaonal Monetary Fund (2016).

27 Caballero et al. (2017).

13

Penning- och valutaPolitik 2018:2

Although the logic of why negave bond yields suggest subopmal scal behavior may

be obvious, a simple numerical example may clarify the issues.

28

Suppose that in 2017, the

market price of a government bond that pays SEK 100 in 2018 is SEK 105, implying a −5

percent annual yield. For the sake of this example, imagine that the bond is bought by the

Riksbank by creding the government’s account at the Riksbank by SEK 105, the amount by

which assets and liabilies of both the government and the Riksbank increase. When the bond

comes due in 2018, the government pays the Riksbank SEK 100, so its assets with the central

bank decline by SEK 100, while its liabilies decline by SEK 105. The mirror of this transacon

has the Riksbank’s assets decline by SEK 105 and its liabilies by SEK 100.

The following year, the government transfers SEK 5 to the private sector, paid for by

creding banks’ deposits at the Riksbank by SEK 5. Government balances with the Riksbank fall

by SEK 5; liabilies of the Riksbank decline by those 5 krona and rise by the equivalent amount

from the increase in bank reserves. Banks’ deposits with the Riksbank earn the repo rate,

which in fall of 2017 was −0.5 percent. If we denote the repo rate by r

D

, then each year the

Riksbank’s liabilies decline by 1 + r

D

< 1 because r

D

< 0. Aer K years, the Riksbank’s liabilies

in the form of bank reserves have declined by −5(1 + r

D

)

K

. Over me, this number gets smaller,

so that the inial expansion in reserves is self-exnguishing and the total expansion in bank

reserves is 5/(1 + r

D

) = 5.025 krona.

This example illustrates one channel by which the private sector can be made beer o

when government bond yields are negave and the government issues addional government

bonds to take advantage of those negave rates. More generally, the government could do

praccally anything producve with the proceeds from negave bond yields – invest in a

sovereign wealth fund, nance infrastructure projects with posive returns, or drop newly

printed cash onto Gamla Stan. A government that does not pursue these policies is reducing

its cizens’ welfare.

-1

0

1

2

3

2014-01 2014-07 2015-01 2015-07 2016-01 2016-07 2017-01 2017-07

Figure 7. Esmated zero-coupon government bond yields

At various maturies, daily data

Source: Sveriges Riksbank

10 year 5 year 3 year 1 year Policy rate

Figure 7 plots esmated government bond yields at maturies of one, three, ve, and 10 years,

along with the path of the repo rate set by the Riksbank. Immediately before and fairly

connuously since the Riksbank adopted a negave repo rate in February 2015, bond yields

out to ve years also turned negave. In August 2016, even the 10-year yield briey irted

with zero. Table 2 reports the average yields over the 33 months since the negave interest

rate policy was adopted. All maturies out to ve years have averaged negave yields for over

two and a half years, plenty of me for the government to adopt welfare-improving policies

that capitalize on bondholders’ willingness to pay for the privilege of lending to the government.

28 This example comes from a conversaon with Jon Faust.

Sweden’S fiScal framework and monetary policy

14

I do not know why governments refuse to issue more bonds when their nominal yields

are negave. But the current scal climate in many countries seems to maintain that any

expansion in government debt is ‘bad,’ while any contracon in debt is ‘good.’ This is a

climate that locks up scal policy and throws away the key.

Table 2. Average of esmated zero-coupon yields

Average between 18 February 2015 and 18 October 2017, daily data.

3-month −0.61

6-month −0.64

1-year −0.64

2-year −0.54

3-year −0.39

4-year −0.23

5-year −0.06

10-year 0.67

Repo −0.42

Source: Sveriges Riksbank

5 How a net-lending target works and why it’s

fragile

Swedish scal policy pursues a net-lending target that is currently one percent of GDP

over the medium term. To understand that policy’s implicaons for government debt

developments, we need to study how government debt evolves over me. Government

debt’s evoluon is governed by the government’s budget identy, which may be wrien as

(1) Q

t

B

t

= (1 + ρQ

t

)B

t−1

−S

t

where B

t

is the nominal value of the government’s bond porolio, Q

t

is the nominal price

of the porolio, and S

t

is the nominal primary budget surplus (the surplus, excluding debt

service costs). The primary surplus is the dierence between total tax revenues and total

government expenditures, excluding interest payments on outstanding debt. As wrien, the

budget identy assumes that all government bonds are in nominal krona. In fact, Sweden

also issues inaon-linked bonds and foreign currency bonds, but in 2017 over half of

Swedish government debt was krona denominated.

We specialize the specicaon of government debt by assuming that all debt pays

zero coupons and that the maturity structure decays at the constant rate ρ each period. If

B

t−1

(t + j) is the quanty of zero-coupon bonds outstanding in period t − 1, which come due

in period t + j, then B

t−1

(t + j) = ρ

j

B

t−1

, where B

t−1

is the porolio of such specialized bonds in

period t − 1.

29

Recent Swedish Naonal Debt Oce guidelines aim for an average maturity of

nominal krona debt of between 4.3 and 5.5 years.

30

Dene the gross nominal rate of return on the bond porolio as

(2) 1 + R

t

=

1 + ρQ

t

Q

t−1

29 This specializaon permits us to extract the implicaons of the existence of a maturity structure for government debt in a

straighorward and intuive manner.

30 Riksgälden Swedish Naonal Debt Oce (2017).

15

Penning- och valutaPolitik 2018:2

This permits expressing the budget identy in terms of the evoluon of the market value of

debt, denoted by Q

t

B

t

, as

(3) Q

t

B

t

= (1 + R

t

)Q

t−1

B

t−1

−S

t

Let N

t

denote net lending by the government, dened as

(4) N

t

=

=

− (Q

t

B

t

− Q

t−1

B

t−1

)

Net borrowing is the change in the market value of outstanding government debt, so net

lending is the negave of this change.

Then we can write the budget identy as

(5) N

t

= − (Q

t

B

t

− Q

t−1

B

t−1

) = S

t

− R

t

Q

t−1

B

t−1

where the term R

t

Q

t−1

B

t−1

reects interest payments on outstanding debt, which is also

called debt service costs.

To relate the budget identy to the government’s net-lending rule, we scale all variables

by nominal GDP, Y

t

, and express raos to aggregate income as lower-case leers. Leng b

t

denote the rao of the market value of debt to GDP, expression (5) becomes

31

(6) n

t

= −

(

b

t

−

1

1 + G

t

b

t−1

)

= s

t

−

R

t

1 + G

t

b

t−1

Denote the net-lending target by n*. When Sweden sets this target at 1 percent

of GDP, n* = 0.01. Government policy aims to achieve this target by adjusng its

scal instruments – taxes, government consumpon and investment, and transfer

payments – which are summarized by the primary surplus, s

t

. We shall treat the primary

surplus as the government’s scal instrument.

5.1 Always on target

Inially, let’s make the simplifying and extreme assumpon that the government hits this

target every period, so that n

t

= n* all the me. Imposing this on the government’s budget

identy in expression (6) implies that

(7) s

t

= n* +

R

t

1 + G

t

b

t−1

This expression is a rule for seng the surplus that makes net lending always equal to its

target. To hit the net-lending target every period, the primary surplus must equal that target

value plus the real interest payments on debt carried over from the past. In this expression,

R

t

/(1 + G

t

)

is the real – inaon-adjusted – rate of return on the government’s bond porolio.

The extreme assumpon produces extreme policy behavior: the government must adjust

the real primary surplus one-for-one with real debt service. This has two consequences. First,

to achieve the net-lending target every period, the government loses the exibility to pursue

other scal goals – macroeconomic stabilizaon, income distribuon, and so forth – even in

the short run. Forcing net lending to be always on target makes primary surpluses the exact

funcon of select economic condions that expression (7) describes.

Second, the government must react to any economic disturbance that raises debt

service by raising the primary surplus. If the Riksbank reduces the repo rate in order to

31 In (6) the variables are dened as b

t

=

=

Q

t

B

t

Y

t

, s

t

=

=

s

t

Y

t

, n

t

=

=

N

t

Y

t

, and 1 + G

t

=

=

Y

t

Y

t−1

=

P

t

P

t−1

y

t

y

t−1

= (1 + π

t

)(1 + g

t

), where G

t

is the net growth

rate of nominal GDP, y

t

, and P

t

is the general price level, so π

t

is the net inaon rate, and g

t

is the net growth rate of real GDP.

Sweden’S fiScal framework and monetary policy

16

smulate inaon, for example, then at least inially real interest rates are likely to fall at all

maturies. This reduces the real return on outstanding debt and, hence, debt service costs.

The government then must reduce primary surpluses – that is, engage in expansionary scal

policy – to maintain the net-lending target.

Many other economic shocks will also aect debt service because interest rates on

government debt are highly sensive to both domesc and foreign disturbances. Any shock

that reduces debt service, must be met with lower primary surpluses if net lending is to stay

on target.

Noce that debt service costs in (7) can be rewrien as

(8)

R

t

1 + g

t

B

t−1

P

t

where 1 + g

t

is real economic growth. Now passive scal behavior is apparent: a higher price

level calls for a lower surplus. In principle, there is no conict between a net-lending target

and passive scal backing for monetary policy. The scal behavior that (7) describes delivers

both the lending target and the scal backing.

5.2 Gradually on target

Neither the Swedish government, nor any government, aims to keep net lending on target

all the me. Instead, the target is intended to be hit on average over the course of economic

cycles. We can generalize this analysis by allowing the adjustment to the net-lending target

to be gradual. One scal rule that gradually achieves the net-lending target is

(9) s

t

− s¯ = − γ(n

t

− n*), γ > 0

where s¯ is the long-run primary surplus-GDP level. By this rule, whenever net lending is

above target, n

t

> n*, the government makes the primary surplus lower than its long-run

value. A lower surplus reduces net lending (or increases government borrowing) to reduce

net lending back to target over me. The rule in (9) is a stylized descripon of scal behavior.

Economic theory oen posits stylized behavior in order to focus aenon on a single aspect

of what policy does – in this case, how surpluses react to net lending. A rule like (9) could be

far more complicated to try to capture actual policy behavior, but that would merely make

the analysis more complex and less transparent.

For this net-lending rule to stabilize government debt and reach the net-lending target

in the long run, primary surpluses must respond to net lending with sucient strength. This

implies a restricon on the coecient γ in (9). To derive that restricon, substute the scal

rule, (9), into the government’s budget identy, (6), to obtain an equaon that describes how

the real market value of outstanding debt-GDP evolves over me

(10) b

t

=

1

1 + G

t

(

1 +

R

t

1 + γ

)

b

t−1

−

s¯ + γn*

1 + γ

Stability requires that over me the market value of debt as a share of output converges to a

constant, which requires that the coecient on lagged debt in (10) lies between 0 and 1

32

(11) 0 <

1

1 + G

t

(

1 +

R

t

1 + γ

)

< 1

Aer some manipulaon, we see that this restricon implies an appropriate range for the

policy parameter γ

32 Technically, the coecient on debt could also lie between 0 and −1, but negave coecients create oscillatory behavior that

governments would usually want to avoid.

17

Penning- och valutaPolitik 2018:2

(12) 1 + γ >

R

t

G

t

Because debt stabilizaon is by nature about the long run, we can consider this condion

when inaon, economic growth, and interest rates are at their constant long-run values.

Substung these long-run relaons in for R/G yields the restricon that government must

make primary surpluses react to net lending with a coecient that sases

(13) γ >

(1 + π*)(r − g)

(1 + π*)(1 + g) − 1

=

(1 + π*)(r − g)

G

This expression has a straighorward interpretaon. π* is the central bank’s inaon target,

so in the case of Sweden, 1 + π* = 1.02, given the Riksbank’s two percent inaon target.

r − g is the dierence between the real interest rate on government bonds and the growth

rate of real GDP in the long run. Economies that permanently grow faster than the cost of

borrowing have no need for scal rules because tax revenues are assured to grow more

rapidly than real debt service; those fortunate economies can simply ‘grow out of decits.’

33

It is reasonable to assume that over the broad span of me in Sweden, the real interest

rate exceeds the real growth rate. The denominator in (13) may be rewrien in terms of

the growth rate of nominal GDP as (1 + π*)(1 + g) − 1 = G, where G is the net growth rate of

nominal GDP, so it is a number like 0.04 when the price level and real output both grow at

two percent annually. Higher nominal growth requires a smaller reacon of surpluses to net

lending for two reasons. First, higher real growth automacally reduces the debt-GDP rao.

Second, higher inaon reduces bond prices and, therefore, the market value of debt.

Table 3 reports threshold values for the responsiveness of surpluses to net lending in

order to stabilize debt-GDP when long-run real interest and growth rates take on dierent

combinaons. Because the rule in (9) is wrien with a −γ, values in the table should be

understood as making surplus deviaons move in the opposite direcon from net-lending

deviaons. These calculaons impose that the Riksbank hits its 2% inaon target in the long

run. When γ exceeds these thresholds, in the long run the debt-GDP rao is constant and

equal to the discounted present value of the long-run primary surplus-GDP rao.

Table 3. Implicaons of combinaons of long-run real interest rates and real growth rates for the

minimum response of primary surpluses to net lending that will stabilize the debt-GDP rao

Growth rate (%)

Real rate (%)

0 1 2 3 4 5

0 0

1 0.51 0

2 1.02 0.34 0

3 1.53 0.68 0.25 0

4 2.04 1.01 0.51 0.20 0

5 2.55 1.35 0.76 0.40 0.17 0

Note. Entries report threshold values that γ in scal rule (9) must exceed. These calculaons assume an

inaon target of 2%. Table excludes the negave threshold values when g > r.

33 Since the global nancial crisis in 2008, many countries have experienced economic growth rates that exceed real interest

rates. Although that experience has been quite persistent, few economists believe it will last forever.

Sweden’S fiScal framework and monetary policy

18

Table 4. Implicaons of combinaons of long-run real interest rates and inaon rate targets for

the minimum response of primary surpluses to net lending that will stabilize the debt-GDP rao

Inaon rate (%)

Real rate (%)

0 1 2 3 4 5

2 0 0 0 0 0 0

3 0.50 0.33 0.25 0.20 0.17 0.15

4 1.00 0.67 0.51 0.41 0.34 0.30

5 1.50 1.00 0.76 0.61 0.51 0.44

Note. Entries report threshold values that γ in scal rule (9) must exceed. These calculaons assume a growth

rate of real GDP of 2%. Table excludes the negave threshold values when g > r.

Table 4 makes clear how the central bank’s inaon target aects this threshold. A higher

inaon target reduces the threshold, perming the debt-GDP rao to be stabilized with

a weaker response of surpluses to net lending. It might seem odd that the inaon target

would have an impact on long-run stabilizaon of the government debt. The reason for

this is that a higher inaon target produces lower bond prices, which reduce the market

value of debt as a share of GDP. A lower market value of debt, on average, makes it easier to

stabilize the rao.

The message is that even in the long run, monetary and scal policies must be consistent

with each other.

5.3 Alternave representaon of scal rule

We can derive an alternave representaon of the scal behavior that underlies the net-

lending target. This representaon es more closely to theorecal work on how monetary

and scal policies interact. Combine (6) with the net-lending rule (9) to arrive at a rule that

sets the primary surplus in response to net interest payments

(14) s

t

=

γ

1 + γ

R

t

1 + G

t

b

t−1

+

1

1 + γ

(s¯ + γn*)

This expression generalizes the extreme policy behavior that appears in (7) when we

assumed the government exactly hit the net-lending target, n*, every period. Whereas in

(7) the government increased the primary surplus one-for-one with interest payments,

expression (14) instructs the government to gradually raise surpluses by the fracon γ/(1 + γ)

of debt service to cover rising interest expenses.

34

Secon 6 reports some esmates of the surplus rules in equaons (9) and (14).

5.4 Net lending vs. change in debt

A policy that targets net lending is a very close cousin to a policy that targets the change in

debt. Net lending is n

t

= −

(

b

t

−

1

1 + G

t

b

t−1

)

, so when nominal GDP growth, G

t

, is zero, this is

simply the change in the market value of the debt-GDP rao. For this reason, it is useful to

study the properes of a policy that targets the change in debt. Let ∆b

t

denote the change in

debt and ∆b* its target value.

Now the government sets policy to raise the primary surplus whenever the change in

debt exceeds target

(15) s

t

− s¯ = δ(∆b

t

− ∆b*)

34 The coecient in (14), γ/(1 + γ), is less than one to make the adjustment gradual.

19

Penning- och valutaPolitik 2018:2

so we restrict δ to be posive. Combining this rule with the government’s budget identy

produces an expression for debt’s evoluon over me

35

(16) b

t

=

(

β

−1

+ δ

1 + δ

)

b

t−1

−

1

1 + δ

(s¯ − δ∆b*)

Debt will be stabilized by this policy only if the coecient

β

−1

+ δ

1 + δ

< 1. But this can never

happen because it requires that real interest rates are negave in the long run.

36

The reason targeng the change in debt can never stabilize the debt-GDP rao is obvious.

If the change in debt target is posive and it is successfully achieved, then debt is growing at

a constant rate as a share of the economy; if the target is negave and achieved, then debt is

declining as a share of the economy. In either case, debt is not a stable fracon of GDP.

The only dierence between a negave change in debt target and a net-lending target

is that net lending scales past debt by the growth rate of nominal GDP. Of course, in periods

when nominal GDP growth is small, posive net lending is essenally equivalent to a

negave change in debt.

5.5 What these scal targets aim to accomplish

Countries adopt scal targets, not because the targets per se are virtuous, but because the

targets help to achieve some broader objecves. Those broader objecves, according to

the Swedish scal policy framework, are to use scal policy to raise the welfare of Swedish

cizens through economic growth, redistribuon of income, and stabilizaon of the macro

economy. As the framework words it, ‘A fundamental precondion for being able to aain

the overall objecve of scal policy is the long-term sustainability of the public nances’.

37

One way to operaonalize ‘long-term sustainability’ is the achievement of a stable debt-GDP

rao over the long run.

Many years ago Phillips (1954) applied the theory of control to categorize three types

of policy rules: proporonal, integral, and derivave. He argued that the main driver of

policy needs to be a proporonal rule. The behavior that equaon (9) describes makes

deviaons of the primary surplus from its long-run value proporonal to deviaons of net

lending from target. One can add to that proporonal behavior a response to cumulated

deviaons of debt from target – the ‘integral’ component – if it is desirable to reduce how

long it takes to return to target. Phillips points out that changes in the deviaon of debt

from target – ’derivave’ part – should be used only to dampen any oscillaons that might

otherwise be present.

Phillips’ point is that a scal response to changes in debt – ’derivaves’ – may serve as

a supplement to, but not a central component of, policy rules that deliver good economic

performance. Because a net-lending target is very close to a change-in-debt target, as I

argued in secon 5.4, Phillips’ argument is that such a target is likely to deliver unstable

outcomes for government debt.

38

Like Switzerland, Sweden stands out among advanced economies by experiencing

declining or at government debt-GDP raos in the wake of the global nancial crisis. Aer

peaking at close to 75 percent during Sweden’s banking and debt crisis in the early 1990s,

central government debt has fallen steadily, as Figure 8 shows. It was about 35 percent when

the global nancial crisis hit in 2008 and is now around 30 percent. This has occurred during

35 As before, we examine how this rule operates over the long run in which interest rates and growth rates are constant.

36 That is, making the coecient on b

t−1

less than 1 requires that 1/β < 1. But β, which determines how

much people discount the future, is always between 0 and 1, implying that people are impaent and prefer to consumer sooner

rather than later.

37 Swedish Government (2011, p. 5).

38 By Phillips’s reasoning, a proporonal rule that is more stable than those underlying either the net-lending or change-in-debt

targets would simply make surpluses depend on deviaons of debt from some target debt-GDP rao, b*. Such a rule would be

s

t

− s¯ = γ(b

t−1

− b*) with γ > β

−1

− 1. This restricon on γ instructs the government to raise surpluses with debt by enough to cover

the increase in real interest payments plus some amount to return debt to target.

Sweden’S fiScal framework and monetary policy

20

a period in which government debt in nearly every other country expanded rapidly and, in

most cases, has remained elevated a decade aer the crisis began.

At one level, this remarkable stability in government debt underscores the success of the

Swedish scal policy framework. At the same me that debt has declined in recent years,

many nominal bond yields have been negave, as secon 4 documents. As I argued in that

secon, Swedish governments have declined the bond market’s oer of a free lunch, which

presents an opportunity to raise welfare among Swedes. Perhaps this is a sign of an overly-

rigid desire to reduce government debt, regardless of prevailing economic condions.

25

35

45

55

65

75

1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017

Figure 8. Swedish central government debt

As a percentage of GDP, annual data

Source: Riksgälden Swedish Naonal Debt Office, Debt Stascs

Government bond developments in Figure 8 are reected in net-lending data. Figure 9 plots

net lending as a percentage of GDP, along with the net-lending target, which was two percent

of GDP unl it was reduced to one percent in 2007. Most notable in this gure is the sharp

increase in net lending over the past few years. In the process of refusing the free lunch, the

government actually chose to reduce its borrowing when the bond market was willing to pay

for the privilege to lend.

-14

-12

-10

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017

Figure 9. Swedish government net lending

As a percentage of GDP, quarterly data

Source: Riksgälden Swedish Naonal Debt Office, Debt Stascs

Net lending (% of GDP) Net lending target (% GDP)

21

Penning- och valutaPolitik 2018:2

6 Some esmates from Swedish data

Can we nd support in Swedish data for the scal policy acons that underlie the net-lending

target? This secon turns to some esmates of Swedish scal policy behavior to address that

queson.

6.1 Esmates of net-lending rule

As a rst pass at applying this theorecal reasoning to Swedish data, I esmate versions of

the scal rule in expression (9), which adjusts the primary surplus to target net lending. Table

5 reports esmates of scal behavior using quarterly data from 1993 through the rst half of

2017.

These esmates do not lend support to the hypothesis that Swedish scal policy

adjusts primary surpluses to target net lending, as scal rule (9) posits. Negave values

of the thresholds in Table 3 give the minimum response of surpluses to net lending – the

γ coecient in the rule – that stabilizes government debt. To return net lending to target,

surpluses must move in the opposite direcon of net lending’s deviaon from target: if net

lending is too high, surpluses must be reduced. Taken at face value, the esmates in the

rst three columns of Table 5 report that when net lending is high, the government raises

surpluses. This reacon does not appear to be consistent with a net-lending target because

it makes net lending increase to deviate farther from target. This paern holds in both the

ordinary least squares and the instrumental variables panels. The instrumental variables

esmates aim to address the fact that the ordinary least squares esmates are contaminated

by the naturally posive relaonship between net lending and the primary surplus that the

government’s budget identy delivers.

The fourth columns in the two panels seem more promising. That specicaon alters

scal rule (9) by making surpluses react to lags in both net lending and in surpluses, a

specicaon that smooths the scal response over me. Although the coecient on lagged

net lending is negave, as stabilizing behavior requires, it is not stascally dierent from 0.

The long-run response of surpluses to net lending takes account of how current surpluses

depend on past surpluses, a dependence that raises the response well above the esmate

of 0.107 reported as the coecient on lagged net lending. But because that coecient is

not stascally signicant, it is dicult to conclude there is strong evidence that scal policy

follows the net-lending rule in equaon (9).

39

The fourth column of the instrumental variables panel reports a somewhat more

signicant coecient on lagged net lending. Unfortunately, the esmate on lagged surpluses

implies that the equaon is not stable, with surpluses exploding over me. This economically

nonsensical esmate makes it hard to take the equaon seriously as a descripon of scal

policy behavior.

39 In the regression s

t

= ρs

t−1

+ γ(n

t−1

− n*) + s¯ , the long-run response of surpluses to past net lending is +γ/(1 − ρ), where in

Table 5, ρ is esmated to be 0.979.

Sweden’S fiScal framework and monetary policy

22

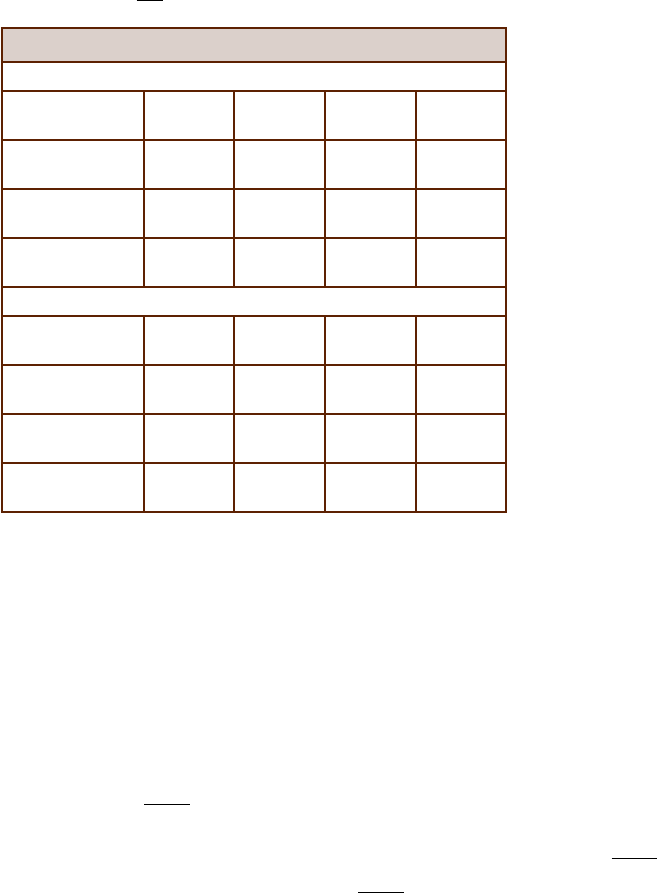

Table 5. Esmates of γ in expression (9)

Dependent variable s

t

Ordinary Least Squares

n

t

0.974***

(0.028)

0.597***

(0.059)

n

t−1

0.848***

(0.043)

−0.107

(0.123)

s

t−1

0.372***

(0.055)

0.979***

(0.121)

const

0.276***

(0.101)

0.321**

(0.155)

0.224***

(0.101)

0.043

(0.125)

Instrumental variables

n

t

0.921***

(0.045)

0.046

(0.108)

n

t−1

0.788***

(0.052)

−0.182*

(0.099)

s

t−1

0.854***

(0.099)

1.073***

(0.103)

const

0.308***

(0.101)

0.374***

(0.133)

0.111

(0.086)

0.042

(0.091)

Note. Dependent variable is primary surplus, s

t

, as percentage of GDP. Independent

variables are n

t

and n

t−1

, net lending as percentage of GDP. Sample for least squares is

1993Q1 to 2017Q2 and for IV is 1994Q4 to 2017Q2. Standard errors in parentheses.

Instruments are two lags each of revenues to GDP, government expenditures to GDP,

nominal GDP growth, CPI inaon, and the repo rate. Signicance levels: ***(1%),

**(5%), *(10%).

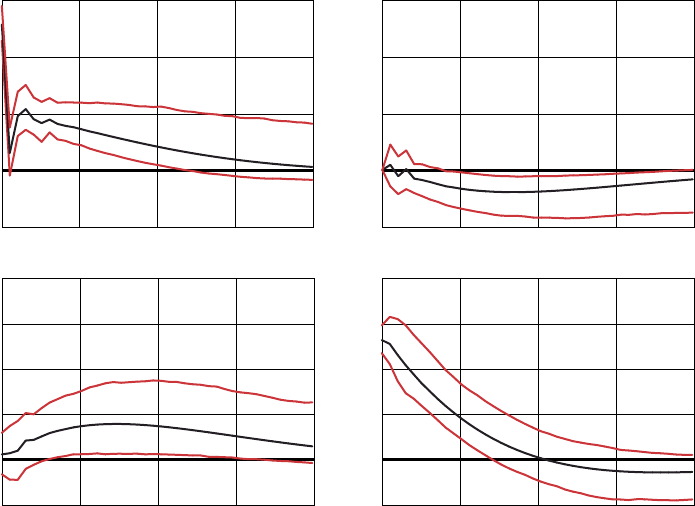

An important shortcoming of the regressions that Table 5 reports is that they do not indicate

how primary surpluses and net lending interact dynamically. Although the simple theory

above makes surpluses respond immediately to higher net lending, in pracce there is

no reason to expect such instantaneous reacon. To explore the dynamic interacons,

we esmate a two-variable vector autoregression (VAR) with the primary surplus and net

lending, both measured as shares of GDP.

40

VAR esmates generalize the regression in

the fourth column of Table 5 in two ways. First, it permits surpluses to respond to current

net lending plus four lags of net lending and surpluses. Second, it models net lending as

depending on lags of surpluses and net lending, so the VAR tracks net lending’s evoluon

over me.

40 The VAR employs the Bayesian methods in Sims and Zha (1998). In their notaon, the prior sets

λ

1

= 1.0, λ

2

= 0.5, λ

3

= 1.0, λ

4

= 0.1, μ

5

= 1.0, μ

6

= 1.0. The VAR includes four lags and a constant term in each equaon and was

esmated over the period 1993Q1 to 2017Q2.

23

Penning- och valutaPolitik 2018:2

-0.3

-0.0

0.3

0.6

0.9

1.2

-0.3

-0.0

0.3

0.6

0.9

1.2

10 20 30 40 10 20 30 40

Net lending Primary surplus

-0.6

-0.3

-0.0

0.3

0.6

0.9

-0.6

-0.3

-0.0

0.3

0.6

0.9

10 20 30 40 10 20 30 40

Note. Horizontal labels are quarters. Dashed lines are 90 percent probability bands.

Figure 10. Dynamic responses to shocks in net lending and primary surpluses

As a percentage of GDP

LendingSurplus

Figure 10 reports how net lending and primary surpluses are correlated with each other

over me. Solid lines are point esmates and dashed lines are 90 percent probability bands.

The le panel of the gure shows that when net lending rises, primary surpluses also rise,

remaining high for about three years. There is some evidence that eventually surpluses

begin to fall, as scal rule (9) calls for, but even aer 10 years the decline in surpluses is not

likely to be dierent from zero. The right panel looks very much like the dynamics that the

government budget identy triggers: higher surpluses raise net lending for some period.

As with the stac regressions in Table 5, the dynamic paerns in Figure 10 do not support

the noon that the Swedish government has systemacally followed a rule that reduces

primary surpluses whenever net lending is above target.

6.2 Response of surpluses to debt service

A central theme of the monetary-scal policy interacons that secon 2 lays out is that for

the central bank to successfully target inaon, scal policy must react in parcular ways.

Whenever monetary policy acons raise (lower) debt service, scal policy must eventually

respond by raising (lowering) primary surpluses. This is the paern of response that the

alternave representaon of scal behavior in equaon (14) reects. We now turn to

Swedish data to seek evidence of this behavior.

Sweden’S fiScal framework and monetary policy

24

Table 6. Esmates of

γ

1 + γ

in expression (9)

Dependent variable s

t

Ordinary least squares

r

t

b

t−1

0.649*

(0.373)

0.183

(0.120)

r

t−1

b

t−2

0.687*

(0.348)

0.107

(0.123)

s

t−1

0.871***

(0.032)

0.872***

(0.033)

const

−0.733*

(0.376)

−0.618*

(0.353)

0.019

(0.123)

0.043

(0.125)

Instrumental variables

n

t

0.408

(0.301)

0.175*

(0.102)

n

t−1

0.308

(0.290)

0.182*

(0.099)

s

t−1

0.889***

(0.034)

0.891***

(0.034)

const

0.067

(0.267)

0.094

(0.266)

0.047

(0.090)

0.042

(0.091)

Note. Dependent variable is primary surplus, s

t

, as percentage of GDP. Independent

variables are r

t

b

t−1

, net interest payments in period t and r

t−1