Special report

Free movement in the EU during the

COVID-19 pandemic

Limited scrutiny of internal border controls, and

uncoordinated actions by Member States

EN

20

22

13

2

Contents

Paragraph

Executive summary I-X

Introduction

01-19

Freedom of movement for persons: a major EU achievement 01-04

The Schengen area

05-09

Internal border controls enforcing COVID-19 travel restrictions

10-13

EU action during the COVID-19 pandemic

14-17

Challenges to and future of the Schengen mechanism

18-19

Audit scope and approach 20-24

Observations

25-75

The Commission’s supervision of Member States’ actions was

limited, and hampered by the legal framework

25-50

The Commission did not properly scrutinise the reintroduction of internal

border controls 26-45

The Commission supervises travel restrictions, but its work is hampered by

limitations in the legal framework 46-50

Despite Commission and ECDC efforts, Member States’ actions

were mostly uncoordinated

51-75

The Commission and the ECDC issued relevant guidance on a timely basis to

facilitate coordination at EU level 53-68

Member States applied uncoordinated approaches to COVID-19-related

internal border and travel restrictions 69-75

Conclusions and recommendations 76-86

Annexes

Annex I – Sample of 10 Member State notifications of internal

border controls between 2015 and 2019

Annex II – Relevant guidance documents issued by the

Commission up to June 2021

4

Executive summary

I The right of EU citizens to move freely within the territory of the EU Member States

is one of the four fundamental freedoms of the European Union. In addition, the

abolition of internal border controls in the Schengen area has allowed a border-free

travel area, which further facilitates the movement of persons.

II Since 2020, the Member States have introduced internal border controls mainly to

enforce the free movement restrictions imposed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The

Schengen legislation stipulates that internal border controls should be proportionate

and a measure of last resort. The Commission remains responsible for monitoring

whether they comply with EU legislation.

III The objective of this audit was to ascertain whether the Commission had taken

effective action to protect the right of free movement of persons during the COVID-19

pandemic. This included the internal Schengen border controls, related travel

restrictions and coordination efforts at EU level. We covered the period until the end

of June 2021 and expect this audit to feed into the ongoing debate on the review of

the Schengen system, including the revision of the Schengen Borders Code.

IV We conclude that while the Commission monitored the free movement

restrictions imposed by the Member States, the limitations of the legal framework

hindered its supervisory role. Furthermore, the Commission did not exercise proper

scrutiny to ensure that internal border controls complied with the Schengen

legislation. We found that the Member States’ notifications of internal border controls

did not provide sufficient evidence that the controls were a measure of last resort,

proportionate and of limited duration. The Member States did not always notify the

Commission of new border controls, or submit the compulsory ex post reports

assessing, among other aspects, the effectiveness and proportionality of their controls

at internal borders. When they were submitted, the reports did not provide sufficient

information on these important aspects.

V The lack of essential information from the Member States affected the

Commission’s ability to carry out a robust analysis of the extent to which the border

control measures complied with the Schengen legislation. However, the Commission

had neither requested additional information from the Member States, nor issued any

opinion on the border controls since the COVID-19 pandemic began.

5

VI Internal border controls were often implemented to enforce a variety of COVID-19

travel restrictions. Although the Commission is responsible for monitoring whether

these restrictions comply with the principle of free movement, the limitations of the

legal framework hampered the Commission’s work in this area. Contrary to the case of

internal border controls, the Member States were not required to inform the

Commission about travel restrictions. In addition, the infringement procedure, which is

the only tool the Commission has to enforce the right of free movement, is unsuitable

for situations like the COVID-19 pandemic.

VII The Commission and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

(ECDC) issued timely guidance to facilitate the coordination of internal border controls

and travel restrictions. However, the guidance on internal border controls lacked

practical details, for example about how Member States should demonstrate

compliance with the principles of proportionality and non-discrimination, as well as

good practices in the management of internal borders during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The ECDC does not comprehensively assess the usefulness and impact of its guidance,

as it is not legally obliged to do so.

VIII The Commission launched important initiatives to coordinate measures

affecting freedom of movement. It also launched a ‘Re-open EU’ portal to consolidate

essential information on travel restrictions for citizens. However, even one year after

the pandemic began, Member States’ practices show that, responses were still mostly

uncoordinated and were not always consistent with Commission guidance and Council

recommendations.

IX Based on these conclusions, we recommend that the Commission should:

— exercise close scrutiny of internal border controls;

— streamline data collection about travel restrictions;

— provide more actionable guidance on the implementation of internal border

controls.

X In addition, the ECDC should improve the monitoring of the extent to which its

guidance is implemented.

6

Introduction

Freedom of movement for persons: a major EU achievement

01 Free movement of persons is the right of European Union (EU) citizens and legally

resident third-country nationals to move and reside freely within the territory of the

EU Member States. It is one of the four fundamental freedoms of the EU (together

with the free movement of goods, services and capital), and has been at the heart of

the European project since its inception. The Treaty on European Union

1

(TEU)

stipulates that “The Union shall offer its citizens an area of freedom, security and

justice without internal frontiers, in which the free movement of persons is ensured

(...)”. Freedom of movement is further enshrined in the Treaty on the Functioning of

the EU

2

(TFEU) and in the Free Movement Directive

3

(FMD).

02 EU citizens value freedom of movement as a particularly significant achievement

of EU integration. “The freedom to travel, study and work anywhere in the EU” is the

most frequently mentioned aspect associated with the European Union, and was

ranked first in all the 27 EU Member States, ahead of the euro and peace

4

.

03 Like other fundamental rights, EU citizens’ right to free movement is not

absolute. EU legislation allows EU citizens’ freedom of movement to be restricted due

to public policy, public security or public health considerations

5

. Such limitations must

be applied in compliance with the general principles of EU law, especially

proportionality and non-discrimination.

04 Free movement of persons within the EU is different from the abolition of

internal border controls in the Schengen area, which has allowed a border-free travel

area. This means that citizens can move freely within the Schengen Area without being

1

Article 3(2) TEU.

2

Article 20(2)(a) and Article 21(1)TFEU.

3

Directive 2004/38/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the

right of citizens of the Union and their family members to move and reside freely within the

territory of the Member States amending Regulation (EEC) No 1612/68 and repealing

Directives 64/221/EEC, 68/360/EEC, 72/194/EEC, 73/148/EEC, 75/34/EEC, 75/35/EEC,

90/364/EEC, 90/365/EEC and 93/96/EEC (Free Movement Directive).

4

Eurobarometer 95 – Spring 2021.

5

Articles 27 and 29 of Directive 2004/38/EC.

7

subject to internal border controls. EU citizens enjoy free movement throughout the

EU, including to and from EU Member States that have not (yet) abolished internal

border controls. While internal border controls per se do not limit freedom of

movement, in practice their absence facilitates the movement of persons.

The Schengen area

05 Border-free travel is governed by the Schengen Agreement, its Implementing

Convention

6

and the Schengen Borders Code (SBC)

7

, the aim being to eliminate

physical border controls between Schengen countries (referred to hereafter as

“internal borders”). At present, 22 EU Member States, as well as Iceland, Norway,

Liechtenstein and Switzerland, participate in Schengen, while some EU Member States

do not: Ireland opted not to participate, and Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, and Romania

are Schengen candidate countries.

06 Although the main purpose of the Schengen legislation is to abolish internal

borders, it allows internal border controls to be temporarily reintroduced in the

following major cases and in full compliance with the general principles of EU law,

especially proportionality and non-discrimination:

o a serious threat to public policy or internal security in a Member State

8

;

o a serious threat to public policy or internal security in a Member State due to

unforeseen events requiring immediate action

9

.

07 Figure 1 describes the process of reintroducing internal border controls in the

Schengen area. It highlights the role and mandate of the Commission, and the Member

States’ obligations.

6

Agreement between the Governments of the States of the Benelux Economic Union, the

Federal Republic of Germany and the French Republic on the gradual abolition of checks at

their common borders; Convention implementing the Schengen Agreement of

14 June 1985 between the Governments of the States of the Benelux Economic Union, the

Federal Republic of Germany and the French Republic on the gradual abolition of checks at

their common borders; OJ L 239, 22.9.2000, pp. 13-18 and pp. 19-62.

7

Regulation (EU) 2016/399 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2016

on a Union Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders

(Schengen Borders Code).

8

Articles 25 and 27 SBC.

9

Article 28 SBC.

8

Figure 1 – Standard workflow for internal border control reintroduction

procedure

Source: ECA.

SCHENGEN

MEMBER STATE

Art. 25, 27, 28 and 29* of the

Schengen Border Code (SBC)

SCHENGEN

MEMBER STATE

Art. 25, 26, 27, 28 SBC

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

Art. 27 and 28 SBC

SCHENGEN

MEMBER STATE

Art. 32 and 33 SBC

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

Art. 33 SBC

SCHENGEN

MEMBER STATE

+

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

Art. 31, 33 and 34 SBC

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

Art. 17

of the Treaty on

European Union

* specific procedure not depicted in this Figure

• Serious threat to public policy or internal security in a Member State

• Serious threat to public policy or internal security in a Member State

requiring immediate action

• Exceptional circumstances putting the overall functioning of the

area without internal border controls at risk

MS Notification

Internal

analysis of the

notification

Request for

additional

information

Negative/Positive

opinion

may issue, if needed

may issue, if needed

shall issue, if concerns about

necessity or proportionality

Implementation of

border control

Ex post report on the

reintroduction of internal

border control

Annual report on the

Schengen area

Internal

analysis of the

report

Negative/Positive

opinion

may issue, if needed

Informing the European Parliament, Council, other Member States and

general public about the reintroduction of internal border controls

Monitoring compliance with EU law as the guardian of EU Treaties

9

08 In addition, under exceptional circumstances that put the overall functioning of

the area without internal border controls at risk as a result of persistent serious

deficiencies relating to external border control, the Commission may propose a

recommendation

10

, to be adopted by the Council, to reintroduce internal border

controls as a matter of last resort. Border controls may be introduced for a period of

up to six months, and can be prolonged for additional six-month periods up to a

maximum of two years. This mechanism was applied in 2016 when the Council

recommended reintroducing internal borders in Denmark, Germany, Austria and

Sweden due to the migration crisis and security threats

11

.

09 The initial decisions to reintroduce internal border controls were made in

response to clearly identifiable short events, in particular major sporting or political

meetings (e.g. the European Football Championship in Austria in 2008 and the NATO

Summit in France in 2009). Since 2015, several Member States have reintroduced

internal border controls in response to perceived threats posed by migration (mainly

due to weaknesses at the external Schengen borders and secondary movements of

irregular migrants from the countries in which they first arrived to their countries of

destination), or security threats (mainly terrorism). Since March 2020, most internal

border controls have been introduced in response to COVID-19. Figure 2 provides an

overview.

10

Article 29 SBC.

11

Council Implementing Decision (EU) 2016/894 of 12 May 2016 setting out a

recommendation for temporary internal border control in exceptional circumstances

putting the overall functioning of the Schengen area at risk.

10

Figure 2 – EU Member States that reintroduced internal Schengen border

controls between 2006 and 2021

N.B.: Some Member States reintroduced border controls for several reasons in a given year.

Source: ECA, based on Member State notifications published on the Commission’s website.

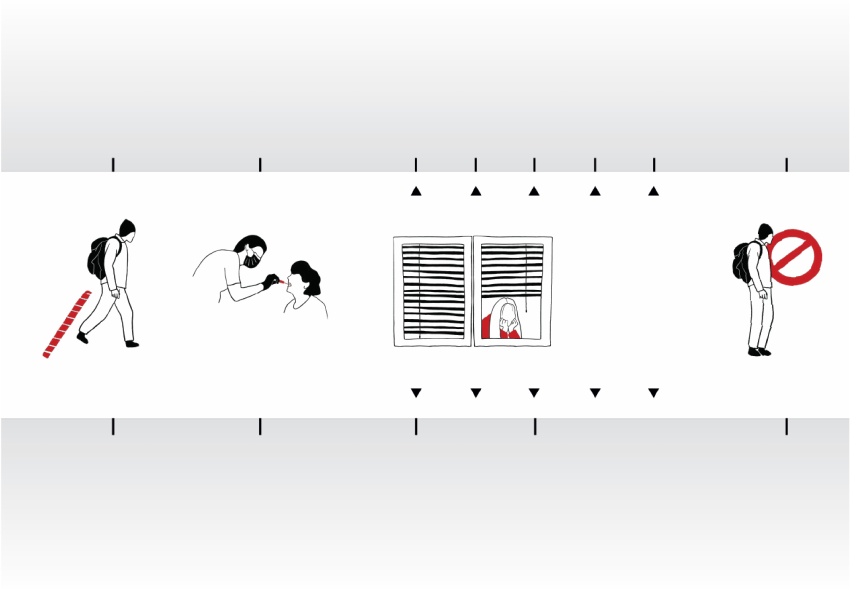

Internal border controls enforcing COVID-19 travel restrictions

10 During the COVID-19 pandemic, Member States have taken measures to restrict

freedom of movement within the EU in an attempt to limit the spread of the virus.

Since March 2020, Member States’ responses to the pandemic have taken different

forms – often combined – including:

o cross-border travel restrictions, such as quarantine or a negative COVID-19 test

requirement; and

o a ban on non-essential travel.

11 In general, internal border controls can be used to check compliance with these

restrictions, e.g. by checking justification for essential travel, possession of a valid

COVID-19 certificate, completion of a passenger locator form, or registration for

quarantine. They allow not only for a systematic compliance check when entering

Reason for reintroduction:

Events (including meetings and conferences)

Security (including terrorism)

Migration (including situation at external borders

and secondary movements)

COVID-19

Number of Member State notifications for each year

One rectangle =

one Member State

(*) data up to

the first half

of 2021

2006 2021*

3

2

3

7

5

3

2

1 3

18

15

18

13

14

99

51

11

national territory, but also for the possibility of refusing entry in the event of non-

compliance. However, internal border controls in the Schengen area may be

reintroduced only as a last resort, and the burden of proof to demonstrate their

proportionality lies with the Member States.

12 Figure 3 provides an overview of internal border controls during the first waves

of the pandemic, between March 2020 and June 2021.

Figure 3 – Overview of internal border controls between March 2020 and

June 2021

Source: ECA, based on Member State notifications published on the Commission’s website.

13 According to the Commission, 14 EU Member States reintroduced internal

Schengen borders to enforce COVID-19 travel restrictions. As the timeline in Figure 4

shows, the peak was reached in April 2020.

EU Schengen Member

States without COVID-19

internal border controls

or notification to the

Commission

EU Schengen Member

States with COVID-19

internal border controls

between March 2020 and

June 2021

EU Schengen Member

States with long-term

internal border controls

due to migration and

security concerns

EU non-Schengen Member

States

12

Figure 4 – Number of EU Member States with COVID-19-related internal

Schengen border controls between March 2020 and June 2021

Source: ECA, based on Member State notifications published on the Commission’s website.

EU action during the COVID-19 pandemic

14 Protecting public health is a national competence. This means that any decision

to implement travel restrictions and to enforce them through border controls lies with

national governments. However, the Commission remains responsible for monitoring

whether these restrictions comply with EU legislation related to freedom of

movement.

15 Furthermore, the Commission – while promoting the general interest of the

Union – should encourage cooperation between Member States. Member States

should liaise with the Commission, and adopt coordinated health policies and

programmes

12

. To this end, the Commission has taken various initiatives, consisting of

guidance, communications and proposals for EU Council recommendations, with the

aim of supporting coordination between the different Member States’ practices.

12

Articles 17 TEU and 168 TFEU.

2020 2021

0 0

13

14 14

6 6 6

5

4

3

7

8 8 8

6

4

14

THE PEAK

was reached

in April 2020

13

16 The Commission has also developed tools to facilitate the safe and free

movement of persons, and to make COVID-19 travel restrictions more transparent and

predictable for citizens. For instance, Re-open EU

13

, which is implemented by the Joint

Research Centre, is a tool that aims to consolidate essential information on borders,

available means of transport, travel restrictions, and public health and safety measures

within the EU. The Commission has proposed and – together with Member States –

developed the EU Digital COVID Certificate

14

to support a more coordinated approach

to travel restrictions between Member States. The EU Digital COVID Certificate is a

framework for issuing, verifying and accepting interoperable COVID-19 vaccination,

test and recovery certificates to facilitate free movement during the pandemic. The

Commission has also set up interoperability platforms to facilitate EU-wide contact-

tracing through passenger locator forms and smartphone applications.

17 In addition to the Commission, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and

Control (ECDC) is an independent EU agency (i.e. not under the Commission’s direct

control) whose mission is to strengthen Europe’s defences against infectious diseases.

It covers a wide spectrum of activities, including surveillance, epidemic intelligence and

scientific advice.

Challenges to and future of the Schengen mechanism

18 Although the Schengen area has never experienced a situation like the COVID-19

pandemic, the border-free travel zone has been challenged by the reintroduction of

internal borders since 2015. The pandemic has come on top of pre-existing tensions

caused by the migration crisis and terrorist threats, with the attendant risk of

“temporary internal border controls becoming semi-permanent in the medium

term”

15

.

19 To address this situation, the Commission published a Schengen Strategy in

June 2021

16

. Among the key actions in the Schengen area without internal border

13

https://reopen.europa.eu/en

14

Regulation (EU) 2021/953 on a framework for the issuance, verification and acceptance of

interoperable COVID-19 vaccination, test and recovery certificates (EU Digital COVID

Certificate) to facilitate free movement during the COVID-19 pandemic.

15

European Parliament resolution of 19.6.2020 on the situation in the Schengen area

following the COVID-19 outbreak (2020/2640(RSP)), paragraph 12.

16

A strategy towards a fully functioning and resilient Schengen area, COM(2021) 277 final.

14

controls, the Strategy presents: (i) political and technical dialogues with Member

States that have reintroduced long-lasting controls at internal borders; (ii) a proposal

for a Regulation amending the SBC; and (iii) codification of the guidelines and

recommendations developed in relation to COVID-19. In December 2021, the

Commission published its proposal for the amended SBC

17

.

17

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending

Regulation (EU) 2016/399 on a Union Code on the rules governing the movement of

persons across borders, COM(2021) 891 final.

15

Audit scope and approach

20 The objective of this audit was to ascertain whether the Commission has taken

effective action to protect the right of free movement of persons during the COVID-19

pandemic. To answer this main audit question, we asked two sub-questions:

(1) Has the Commission effectively scrutinised internal Schengen border controls and

travel restrictions?

(2) Has the Commission facilitated coordinated action by Member States to mitigate

the impact of internal Schengen border controls and travel restrictions?

21 In recent years, our audit reports have covered the external border element of

the Schengen Strategy: hotspots in Greece and Italy

18

, migration management

(including asylum and relocation procedures)

19

, IT systems

20

, Frontex operations

21

,

returns and readmission policy

22

, and Europol’s support to fight migrant smuggling

23

.

22 This audit looks into the internal border element of the Schengen Strategy. In

particular, we examined the Commission’s scrutiny of the internal border controls and

travel restrictions introduced by the Member States, as well as the actions taken by

the Commission at the start of the pandemic to facilitate coordinated action. We

expect this audit to feed into the ongoing debate on the review of the Schengen

system, including the revision of the Schengen Borders Code. The audit covers the

period from March 2020 to June 2021 (see Figure 5).

18

Special report 06/2017: EU response to the refugee crisis: the ‘hotspot’ approach.

19

Special report 24/2019: Asylum, relocation and return of migrants: Time to step up action

to address disparities between objectives and results.

20

Special report 20/2019: EU information systems supporting border control – a strong tool,

but more focus needed on timely and complete data.

21

Special report 08/2021: Frontex’s support to external border management: not sufficiently

effective to date.

22

Special report 17/2021: EU readmission cooperation with third countries: relevant actions

yielded limited results.

23

Special report 19/2021: Europol support to fight migrant smuggling: a valued partner, but

insufficient use of data sources and result measurement.

16

Figure 5 – Focus of the audit

Source: ECA.

23 We carried out the audit via desk review, written questionnaires and interviews

with relevant stakeholders, such as the Commission, the ECDC and the Joint Research

Centre. We performed a documentary review and analysis of:

o relevant EU legislation, including the FMD and the SBC, to identify the key

regulatory requirements and the responsibilities of the different stakeholders;

o all 150 notifications by EU Member States of the temporary reintroduction of

internal border controls between March 2020 and June 2021, and all available

ex post reports by Member States related to these notifications;

o a sample of 10 Member States’ notifications and the Commission’s related

internal documentation for internal border controls reintroduced between 2015

and 2019. We examined these notifications to compare the Commission’s scrutiny

of internal border notifications before and after the COVID-19 pandemic;

o the Commission’s internal documents, including a review of 33 meeting reports of

the Corona Information Group (see paragraph 69), and monitoring of the

temporary reintroduction of internal border controls and travel restrictions.

In addition, we met representatives of six national representations to the EU, selected

to obtain balanced geographical coverage (Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Lithuania,

Portugal and Slovenia).

24 The audit scope focuses on the EU citizen’s perspective when travelling within the

EU. Specific rights for third-country nationals, including rights to ask for international

protection and to seek asylum in the EU, are not included. Also, the audit did not cover

non-EU Schengen countries (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland).

March 2020

to June 2021

Guardian of

EU treaties

Guidance and

coordination

European Commission

Internal Schengen

border controls as

a tool...

...for enforcing

COVID-19-related

travel restrictions

17

Observations

The Commission’s supervision of Member States’ actions was

limited, and hampered by the legal framework

25 In the paragraphs below, we examine whether:

(a) the Commission properly scrutinised the Member States’ temporary

reintroduction of internal border controls during the COVID-19 pandemic. This

included not only the border controls triggered by the pandemic, but also those

triggered by the preceding migration crisis and security threats, and which were

still in place during the pandemic. Furthermore, we examined whether the

Commission made full use of the possibilities offered by the legal framework to

enforce Member States’ compliance with EU legislation;

(b) the Commission assessed in a systematic and timely manner whether the travel

restrictions imposed by the Member States complied with the applicable EU

legislation. Furthermore, we examined whether the Commission took action

when it identified potential issues of non-compliance during the period covered

by the audit.

The Commission did not properly scrutinise the reintroduction of

internal border controls

26 The Schengen legal provisions lay down strict reasons, maximum durations and

procedural requirements for reintroducing internal border controls. The burden of

proof lies with the Member States to demonstrate that there are no (better)

alternatives to border controls, and that the use of border controls is justified as a last

resort. When reintroducing internal borders, the Member States are required to notify

the Commission. The notifications need to be timely, and contain all the information

necessary for the Commission’s assessments.

27 When a Member State notification does not contain sufficient information, the

Commission should request additional details. If the Commission has concerns about

compliance with EU law, it may issue an opinion to publicly express its position on the

internal border control in question. Furthermore, if the Commission has concerns

about the proportionality of and need for the measure, “it shall issue an opinion to

that effect” (see paragraphs 06-08 and Figure 1).

18

Border controls introduced before the pandemic

28 The Council recommended

24

to Denmark, Germany, Austria and Sweden, which

had been severely affected by the migration crisis and security threats, that they

should retain proportionate temporary border controls for a maximum period of six

months. This recommendation was made three more times (in November 2016, and in

February and May 2017

25

) until November 2017.

29 We examined a sample of internal border notifications issued between 2015

and 2019 to compare the Commission’s scrutiny before and after the COVID-19

pandemic (see Annex I). We found that four of the 10 notifications examined (those

issued since November 2017) did not contain sufficient information to allow the

Commission to assess the proportionality of the respective border control measures. In

particular, they lacked justification that they were indeed a last resort in the absence

of any alternative. Although the Commission requested additional information from

the Member States in all four cases, the replies it received were still insufficient to

allow a robust assessment.

30 Since 2020, the content of Member States’ notifications relating to migration or

security threats has continued to be insufficient for the Commission to assess the

proportionality of border controls (see paragraphs 37 and 38). However, due to a

significant increase in COVID-19-related notifications, the Commission has stopped

requesting additional information.

31 According to the Schengen Borders Code, internal border controls can be

reintroduced for a maximum of two years. Five Member States (Denmark, Germany,

France, Austria and Sweden) exceeded this period by changing the legal grounds every

two years, or by claiming that a new notification represents a new border control

(rather than an existing control being prolonged). Despite this, the Commission issued

only one joint favourable opinion on the proportionality and necessity of internal

border controls for Austria and Germany in October 2015

26

.

24

Council Implementing Decision (EU) 2016/894 of 12 May 2016 setting out a

recommendation for temporary internal border control in exceptional circumstances

putting the overall functioning of the Schengen area at risk.

25

Council Implementing Decision (EU) 2016/1989 of 11 November 2016, Council

Implementing Decision (EU) 2017/246 of 7 February 2017 and Council Implementing

decision 2017/818 of 11 May 2017.

26

The Commission’s opinion of 23.10.2015, C(2015) 7100 final.

19

32 All Member States are required to report to the European Parliament, the Council

and the Commission on the implementation of border controls within four weeks of

their being lifted

27

. However, the five Member States with long-term border controls

mentioned in paragraph 31 have still not submitted an ex post report six years after

they were reintroduced. The Commission took no action to acquire information on the

implementation of these controls.

33 For the Commission, the extent and duration of long-term internal border

controls is neither proportionate nor necessary

28

. The Commission has the mandate

and obligation to monitor compliance with EU law, and to act in cases of potential non-

compliance (see paragraph 14). It can launch infringement procedures, but has not yet

done so despite its concerns that internal border controls do not comply with EU law.

34 The Commission has instead opted for soft measures, i.e. dialogue with Member

States and coordination, but with no apparent results, as the internal border controls

reintroduced more than six years ago are still in place. In the June 2021 Schengen

Strategy, the Commission expressed its intention to make use of the legal means at its

disposal in cases where Member States disproportionately prolong controls at internal

borders.

Border controls related to the COVID-19 pandemic

35 Although the Schengen Borders Code does not specifically mention a threat to

public health as a reason for introducing controls at internal borders, in view of the

COVID-19 pandemic the Commission accepted that a public health threat could

constitute a threat to public policy, thus allowing a Member State to reintroduce

controls of this kind. In such a case, though, the Member State needs to satisfy a strict

requirement that internal border controls are not only a measure of last resort, but are

also proportionate and limited in duration.

36 While border controls can be used to check the essential nature of travel,

together with testing and registration for quarantine (but not quarantine itself), other

27

Article 33 SBC.

28

Impact Assessment Report accompanying the document Proposal for a Regulation of the

European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation (EU) 2016/399 on a Union

Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders, SWD(2021) 462

final.

20

checks could be made by police

29

or health officials

30

(e.g. temperature screening)

instead of border controls to limit the spread of the virus.

37 We have reviewed all 150 Member State notifications of internal border controls

that were submitted to the Commission between March 2020 and June 2021, of which

135 related exclusively to COVID-19, six to COVID-19 and migration or security; and the

remaining nine to migration and/or security (see paragraph 30). Our review shows that

all notifications indicated the dates, duration and scope of border controls. However,

they did not provide sufficient evidence (backed by comprehensive statistical data and

comparative analysis of various alternatives to border controls) to demonstrate that

the border controls were indeed a last resort. Furthermore, they often failed to list the

authorised border crossings to which the controls would apply. For more details, see

Figure 6.

Figure 6 – Review of EU Member State notifications

Source: ECA.

38 Our review shows the same issues as for the notifications relating to the

migration crisis and security threats before the COVID-19 pandemic

(see paragraph 29). Although the information the Member States provided was

insufficient, the Commission has neither requested additional information, nor issued

any opinion since the COVID-19 pandemic began as required by Article 27 of the SBC.

We conclude that this lack of essential information from the Member States has

29

Commission Recommendation (EU) 2017/820 of 12 May 2017 on proportionate use of

police checks and police cooperation in the Schengen area, C(2017) 3349 final.

30

Paragraph 20 of the Guidelines for border management measures to protect health and

ensure the availability of goods and essential services, 16.3.2020 C(2020) 1753 final.

150EU Member State notifications examined

from January 2020 to June 2021

Date, duration

and scope

List of authorised border

crossings provided

Reasons for reintroduction

containing detailed data

Proportionality/last resort

sufficiently demonstrated

0 % 20 % 40 % 60 % 80 % 100 %

0

13

89

150

21

affected the Commission’s ability to carry out a robust legal analysis of individual

border control measures.

39 In addition, the Commission has no robust monitoring system in place to identify

cases of border controls of which the Member States have not provided notification.

During the audit, the Commission stated that it was not aware of any such cases, but

Box 1 below shows two examples we were able to identify.

Box 1

Examples of COVID-19-related border controls of which the

Commission was not notified

In summer 2020 and spring 2021, Slovenia reintroduced COVID-19-related border

controls at all its borders. The controls carried out by border police were mainly

used to ensure registration for mandatory quarantine or verification of a negative

COVID-19 test. The Commission was not notified of these controls.

In spring and summer 2021, Slovakia reintroduced border controls. They were

used to verify registration first for mandatory quarantine and later for the

COVID-19 certificate. Although Slovakia notified the Commission of border

controls in 2020, they did not do so in 2021.

In both cases, in the absence of formal notification, the Member States did not

report on the implementation of their border controls, and did not demonstrate

that they were proportionate or necessary.

40 The Commission did not obtain all the ex post reports it was supposed to receive

within four weeks of the end of internal border controls (see also paragraph 32).

Table 1 lists the Member States that did not submit ex post reports on COVID-19-

related internal border controls. The Commission did not provide evidence that it had

asked these Member States to send the missing notifications or ex post reports.

22

Table 1 – List of Member States that had not submitted ex post reports

on COVID-19 internal border controls by September 2021

Member State Situation

Belgium

Ex post reports submitted for border controls in 2020, but

not (yet) for border controls in 2021.

Portugal

Denmark

No ex post reports submitted for COVID-19 border controls,

either in 2020 or 2021.

Germany

France

Austria

Poland

No notifications of border controls in 2021. We therefore

assume that no ex post reports will be submitted.

Slovakia

Slovenia

No notification of border controls sent to the Commission,

either in 2020 or 2021. We therefore assume that no ex post

reports will be submitted.

Source: ECA, based on the review of ex post reports obtained from the Commission.

41 Our review of all the 12 ex post reports received by the Commission for the

March 2020 – June 2021 period shows that the reports vary greatly from general

statements to detailed statistics, but most of them did not fully comply with legal

requirements regarding the assessment of proportionality

31

. Ten of the 12 reports did

not cover this aspect sufficiently, but only very briefly and in general terms (see Box 2).

Only three reports mentioned the possible use of alternative measures, but again only

very briefly.

Box 2

Example of insufficient justification of proportionality in ex post

reports

Report 1 covering March – June 2020 in Hungary: “The measures introduced were

effective, proportionate and crucial in limiting the spread of the epidemic, given

that the number of cases in Hungary was kept low.”

31

Article 33 SBC.

23

Report 2 covering March – June 2020 in Portugal: “Considering the global

epidemiological situation, the main purpose and the objectives of the temporary

reintroduction was the safeguard of public health and the containment of

contagion of the COVID-19 virus. In this context, the reintroduction of internal

border controls was limited in operational and geographic standards to the needs

of guaranteeing the protection of public health and internal security.”

Report 3 covering March – June 2020 in Spain: “As expected, due to the very

objectives pursued with the reintroduction of controls, the free movement of

persons has been seriously affected. However, if the measures adopted within

Spanish territory, in the other Member States and Schengen associated States,

and at the other internal borders of the Schengen area are taken into account, the

measure can be considered to have been proportionate.”

42 None of the reports described the measures put in place to ensure compliance

with the principle of non-discrimination, especially as regards the equal treatment of

EU citizens, irrespective of nationality. Although not explicitly required by the

Schengen Borders Code, this information is relevant for assessing the legality of border

controls put in place to enforce restrictions in the form of travel bans based on

nationality or residence (see Box 3).

Box 3

Example of a border control used to enforce a travel ban, and its

potential impact on the principle of non-discrimination

In autumn 2020, Hungary used its internal border controls to enforce travel

restrictions by applying different rules for Hungarian citizens than for other EU

citizens, irrespective of the pandemic situation prevailing in EU Member States at

the time.

From 1 September 2020, Hungary decided not to allow foreign nationals, including

EU citizens, to travel to the country. The only exemption granted was for ‘Visegrad

Four’ (i.e. Czech, Polish and Slovak) citizens who could provide evidence of a

negative COVID-19 test.

On 1 October 2020, mandatory quarantine upon entry was introduced, but

Hungarian citizens and family members returning to Hungary from Czechia, Poland

and Slovakia were exempt from quarantine if they presented a negative test

result.

24

Also, citizens of Czechia, Poland and Slovakia who booked accommodation in

Hungary during October were excluded from quarantine rules if they presented a

negative PCR test result upon arrival in Hungary.

43 Lastly, as regards comprehensive annual reporting on the overall implementation

of Schengen (including the implementation of internal border controls and the

Commission’s views on the justification for them), the Commission has not issued an

annual report on the functioning of the area without internal borders since 2015

32

.

44 The European Parliament called on the Commission to exercise appropriate

scrutiny over the application of the Schengen acquis, to make use of its prerogatives to

request additional information from Member States, and to enhance its reporting to

the European Parliament on how it exercises its prerogatives under the Treaties

33

.

45 Figure 7 shows the weaknesses we found in the Commission’s scrutiny of the

internal Schengen borders.

32

As required by Article 33 SBC.

33

For example, European Parliament resolution of 19.6.2020 on the situation in the Schengen

area following the COVID-19 outbreak (2020/2640(RSP)).

25

Figure 7 – Weaknesses found in internal border control reintroduction

Source: ECA.

SCHENGEN

MEMBER STATE

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

SCHENGEN

MEMBER STATE

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

SCHENGEN

MEMBER STATE

+

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

MS Notification

Internal

analysis of the

notification

Request for

additional

information

Negative/Positive

opinion

may issue, if needed

may issue, if needed

shall issue, if concerns about

necessity or proportionality

Implementation of

border control

Ex post report on the

reintroduction of internal

border control

Annual report on the

Schengen area

Internal

analysis of the

report

Negative/Positive

opinion

may issue, if needed

Informing the European Parliament, Council, other Member States and

the general public about the reintroduction of internal border controls

Monitoring compliance with EU law as the guardian of EU Treaties

Insufficient information for a robust internal

analysis (paragraphs 30, 32, 37-38 and 40-42)

No monitoring of border controls not

notified to the Commission (39)

No request for additional information

since 2020 (30, 32, 38 and 40)

No opinion issued since 2015 (31 and 38)

No opinion issued in the event of concerns about

proportionality (31 and 33)

No annual report on the Schengen area

since 2015 (43)

Calls from EU Parliament to improve

reporting (44)

Lack of enforcement action/infringement (33-34)

26

The Commission supervises travel restrictions, but its work is hampered

by limitations in the legal framework

46 Member States reacted to the pandemic by imposing travel restrictions on the

grounds of protecting public health (see paragraph 10). We found that, overall, the

Commission does not have a robust legal framework to assess whether the Member

States’ travel restrictions complied with EU law. The main reasons are the following:

o the substantial powers and prerogatives of Member States in terms of public

health under EU law, an area which does not fall within the EU’s exclusive or

shared competence

34

and Member States determining their own health

policies

35

;

o the FMD

36

does not require Member States to notify the Commission of, or report

on, the measures they adopt under this directive. This is due to the functioning of

the FMD in general, where restrictions on free movement apply on the basis of an

individual assessment and are subject to judicial control. As there is no obligation,

Member States are free to decide whether or not they will report on the

measures adopted, including travel restrictions, and what form that reporting will

take. This increases the risk that the information the Commission receives about

travel restrictions is not complete;

o the non-binding nature of the Council Recommendations

37

, which is the main

policy document for a coordinated approach to restrictions on free movement in

response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and thus includes common principles agreed

by the Member States when implementing travel restrictions;

o the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and its rapid evolution.

47 In addition, the only tool the Commission has to ensure that travel restrictions

comply with the right of free movement is the infringement procedure, which is not

suitable in the context of a pandemic. This is due to the length of legal proceedings

(which often take several years at the European Court of Justice), combined with the

short-term and variable nature of the measures taken by the Member States during

34

See Article 3 TFEU, Article 45(3) TFEU, and Articles 27 and 29 FMD.

35

See Articles 4(2)(k) and 6(a) TFEU.

36

Directive 2004/38/EC.

37

Council Recommendations (EU) 2020/1475 of 13.10.2020, (EU) 2021/119 of 1.2.2021,

EU 2021/961 of 14.6.2021 and (EU) 2022/107 of 25.1.2022.

27

the pandemic. Previous Court rulings

38

have determined that the infringement

procedure becomes inadmissible when the breach disappears. As it is very unlikely that

the measures that the Commission currently considers to be non-compliant will still be

in force several years from now, this means that a non-compliant Member State will

not be sanctioned).

48 When monitoring the travel restrictions imposed by the Member States, the

Commission used several sources of information, such as national legislation posted on

government websites, direct contact with the Member States, information available in

the media, or complaints about specific problems from other Member States, citizens

or organisations.

49 Within the limitations of the legal framework, the evidence we obtained shows

that the Commission assessed the travel restrictions in a systematic and timely manner

when it received notification of them. However, we found that the data reported by

the Member States were often not comparable, and contained information gaps. This

made it more difficult for the Commission to obtain a timely and accurate picture of

the travel restrictions the Member States had imposed, and thus to fulfil its

compliance monitoring duties (see example in Box 4).

Box 4

Examples of problems with the data reported by the Member States

The Commission’s monitoring in June 2021 was based on the information received

from national authorities. It included the question “Do you already apply the

mechanism established by the Council Recommendations (common map,

thresholds, etc.)?” Eight Member States did not reply to this question (Bulgaria,

Croatia, Italy, Hungary, Netherlands, Austria, Poland and Slovakia).

In June 2021, the Commission also mentioned difficulties with collecting complete

and comparable data at EU level in its communication on the lessons learned from

the COVID-19 pandemic

39

.

38

See Case C 288/12 (paragraph 30), Case C 221/04 (paragraphs 25 and 26), and Case C-20/09

(paragraph 33).

39

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council,

the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the

Regions: Drawing the early lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic, COM(2021)-380 final.

28

50 Difficulties were encountered not only by the Commission, but also by the ECDC.

The Council Recommendation on a coordinated approach to restricting free movement

in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

40

requires the ECDC to publish weekly maps of

risk areas. These maps

41

disseminate data on COVID-19 transmission in the different

areas, and aim to support the Member States in their decision-making on free

movement. The Council Recommendation required Member States to report data at

regional level on a weekly basis. After six months (in May 2021), 12 Member States

had still not complied with this requirement.

Despite Commission and ECDC efforts, Member States’ actions

were mostly uncoordinated

51 As the EU had no health emergency framework in place, the Member States had

to respond quickly to a constantly evolving health situation. Although responsibility for

implementing COVID-19 travel restrictions lies solely with the Member States, the

Commission’s mandate is to liaise with the Member States to facilitate a coordinated

approach to these restrictions so as to minimise the impact on cross-border travel

within the EU (see paragraph 15).

52 In this section, we examine whether:

(a) the Commission and the ECDC issued relevant guidance, opinions and

recommendations on a timely basis to facilitate coordination of the Member

States’ actions, and adapted them to take account of new developments; and

(b) the Commission’s and the ECDC’s efforts resulted in a more consistent and better

coordinated application of travel restrictions and internal border management by

the Member States.

40

Council Recommendation (EU) 2020/1475.

41

https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/situation-updates/weekly-maps-coordinated-

restriction-free-movement

29

The Commission and the ECDC issued relevant guidance on a timely basis

to facilitate coordination at EU level

The Commission

53 Since the start of the pandemic, the Commission has issued extensive guidance

documents for the Member States in the form of communications, guidelines and

proposals for Council recommendations. These have covered various aspects of

freedom of movement and COVID-19 measures (see Annex II).

54 As regards EU guidance on border controls, the two main areas covered by the

Commission were the ban on non-essential travel to the EU (external borders) and

guidelines on border management (internal borders), and its subsequent

communication on the gradual lifting of border controls. Guidance on the ban on non-

essential travel to the EU lies outside the scope of this audit (see paragraph 22).

55 The guidelines on border management were published on 16 March 2020

42

in the

early days of the pandemic, and covered the main aspects of border management (i.e.

border control measures at internal and external borders, health-related measures,

and the transport of goods). These guidelines reminded the Member States of basic

legal principles, including proportionality and non-discrimination, and contained a

dedicated section on internal border controls which acknowledged that such controls

could be reintroduced, “in an extremely critical situation”

43

, as a reaction to COVID-19.

We consider this guidance to be timely and relevant.

56 However, we identified the following weaknesses in the Commission’s guidance:

o the March 2020 guidelines did not provide detailed advice on how the Member

States could ensure (and demonstrate) that their border controls complied with

the general principle of proportionality in the specific context of the pandemic;

o there was no practical guidance, including examples of good practice in border

management throughout the pandemic. For example, the Practical Handbook for

Border Guards, which serves as a user guide for border guards when conducting

42

Covid-19 Guidelines for border management measures to protect health and ensure the

availability of goods and essential services, 16.3.2020 C(2020) 1753 final.

43

Paragraph 18 of the Guidelines for border management measures to protect health and

ensure the availability of goods and essential services, 16.3.2020 C(2020) 1753 final.

30

their border control activities

44

, has not been updated to take account of the

pandemic (except for incorporating the certificate for international transport

workers);

o certain terms used in the guidance were not well defined in the context of a

pandemic. The March 2020 Guidelines for border management mention health

checks, of which the Commission does not need to be notified, as a potential

alternative to border controls

45

. However, the difference between border

controls and health checks at the borders in a COVID-19 context has not been

clearly defined. There is therefore a risk that Member States may implement

health checks which are de facto border controls, but which are not reported to

the Commission; and

o the term ‘border closure’ was also frequently used in the Commission and ECDC

guidance and in the Council recommendations. The term is not actually defined in

the Schengen Borders Code, and is potentially misleading for the general public

travelling within the Schengen area, because intra-EU borders have not been fully

closed. Only entry (and occasionally exit) was restricted, or certain border

crossings were temporarily closed.

57 In addition to the guidance on border management, the Commission issued

extensive guidance on various aspects relating to freedom of movement (see Annex II).

This included specific issues affecting workers and seasonal workers, ‘Green Lanes’

(the availability of goods and essential services), transport services and connectivity,

air cargo operations, repatriation and travel arrangements for seafarers, passengers

and other persons on board ships, tourism, serious cross-border threats to health, and

the use of rapid antigen tests.

58 Of particular importance were the Commission’s proposals for the Council

Recommendations for a coordinated approach to restrictions on free movement in

response to the COVID-19 pandemic

46

. In these documents, the Member States agreed

on common criteria for assessing regional epidemiological conditions. They also agreed

44

Annex to the Commission Recommendation C(2019) 7131 final of 8.10.2019 establishing a

common “Practical Handbook for Border Guards” to be used by Member States' competent

authorities when carrying out the border control of persons and replacing Commission

Recommendation C(2006) 5186 of 6 November 2006.

45

Paragraph 20, C(2020) 1753 final, 16.3.2020.

46

COM(2020) 499 final, 4.9.2020; COM(2020) 849 final, 18.12.2020 and COM(2021) 232 final,

3.5.2021.

31

to use a common colour map of the regions and countries within the European

Economic Area: from green to yellow and red according to their rates of COVID-19

notifications and testing, and the percentage of positive tests. The need to adapt to

the evolving situation was reflected in the two updates adopted in February and

in June 2021

47

.

59 The Commission also acted swiftly to provide support for tackling issues relating

to freedom of movement for specific categories of persons, in particular transport

personnel and seasonal workers. As early as March 2020, it issued practical guidelines

supporting the principle that all EU internal borders should stay open to freight, and

that supply chains for essential products must be guaranteed

48

. In July 2020, the

Commission issued similar guidelines to support seasonal workers

49

.

60 One major achievement by the Commission in this area was establishing the

‘Green Lanes’ concept in March 2020

50

, thereby ensuring the continuous flow of goods

across the EU and the free movement of transport personnel which were affected by

the reintroduction of internal border controls, particularly in the early days of the

pandemic. The Commission, in cooperation with the Member States, set up a National

Transport Contact Points Network that proved to be an effective tool for triggering

quick, coordinated action between transport ministries and the Commission

(see Box 5).

Box 5

Green Lanes: an example of good practice

To support the free movement of transport workers and the flow of goods across

the EU, the Commission worked with the EU Agency for the Space Programme on

developing a “green lane” mobile app (see images below). As well as allowing lorry

drivers and authorities to track border crossing times at the EU’s internal borders,

47

Council Recommendations (EU) 2021/961 of 14.6.2021 and (EU) 2021/119 of 1.2.2021.

48

Communication from the Commission on the implementation of the Green Lanes under the

Guidelines for border management measures to protect health and ensure the availability

of goods and essential services, C(2020) 1897 final.

49

Communication from the Commission Guidelines on seasonal workers in the EU in the

context of the COVID-19 outbreak, C(2020) 4813 final.

50

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_510

32

the app also tracks average border crossing times each day covering all the

178 border crossing points along the internal TEN-T network and several border

crossing points at the external border of the EU. By checking real-time traffic,

drivers can take informed decisions about when and where to cross each border,

and authorities are able to plan ahead to minimise the impact of congestion or

traffic disruption.

Source: EU Agency for the Space Programme.

61 On 15 June 2020, the Commission launched a web platform to support the safe

re-opening of travel and tourism across Europe (‘Re-open EU’

51

). The platform is based

on the voluntary information that EU countries provide about travel restrictions, and

public health and safety measures, and aims to rebuild confidence in travel in the EU

by informing citizens about the restrictions that apply in each Member State, the aim

being to facilitate their travel plans

52

.

62 Although this is a very positive initiative by the EU, its success depends on

cooperation by the Member States. In particular, Member States should regularly

51

https://reopen.europa.eu/en

52

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1045

33

provide official information that is complete and up to date. We also raised this issue

in our special report on air passenger rights during the COVID-19 pandemic

53

.

63 As at 5 July 2021 (i.e. more than one year after Re-open EU was launched), nine

Member States (Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, France, Romania, Slovenia,

Finland and Sweden) were still not providing updated information. The risk here is that

EU citizens may question the usefulness of the tool when they encounter problems at

the borders, because the information they have used to plan their journey is incorrect

or outdated.

The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

64 During the audited period, the ECDC published 27 risk/threat assessments and

more than 70 guidance and technical reports on the pandemic. Its first travel guidance

dates back to May 2020. The ECDC also provided input for the Commission’s guidance

on border controls and travel restrictions.

65 In May 2020, the ECDC issued guidance stating that border closures could delay

the introduction of the virus into a country. However, such closures would have to be

almost total and be implemented rapidly during the early phases of an epidemic,

something which the ECDC believed would only be feasible in specific contexts (e.g. for

small, isolated island nations)

54

. In practice, however, Member States did not always

follow this guidance, and border controls were reintroduced between interconnected

countries in the Schengen area. Box 6 provides an example of the challenges to the

effectiveness of land border controls in such cases.

53

Special report 15/2021: Air passenger rights during the COVID-19 pandemic: Key rights not

protected despite Commission efforts, paragraphs 68-70 and recommendation 3(a).

54

Considerations for travel-related measures to reduce spread of COVID-19 in the EU/EEA,

26.5.2020.

34

Box 6

Example of challenges to the effectiveness of Schengen land border

controls

On 16 March 2020, Germany reintroduced temporary border checks at its land

borders with Austria, Denmark, France, Luxembourg and Switzerland the aim

being to enforce a non-essential travel ban. The checks at the border with

Luxembourg were carried out for two months (until 15 May 2020), and led to the

closure of several smaller border-crossing points. In April 2020, the COVID-19 virus

was already widespread in Germany. Furthermore, as the Luxembourg/Belgium

and Belgium/Germany borders remained open in the first three weeks, it was

possible for Luxembourg residents to bypass these checks by passing through

Belgium.

On 14 February 2021, Germany reintroduced internal border controls with Czechia

and the Tyrol region in Austria to prevent the spread of virus mutations. It applied

a stricter non-essential travel ban than before, not even allowing transit through

Germany to the country of residence. However, it kept its borders with Poland

open. As there were no border controls between Poland and Czechia, it was

possible to bypass border controls there as well.

66 In November 2020, the ECDC prepared a ‘Strategic and performance analysis of

ECDC response to the COVID-19 pandemic’

55

, which looked at the usability of the

Centre’s COVID-19 outputs through surveys and focus groups. The document

concludes that the Centre’s guidance could be more practical and actionable.

67 The ECDC does not collect detailed information to verify how countries have

implemented its guidance, as it is under no obligation to do so.

68 ECDC guidance is not binding on Member States, as the Centre does not have

regulatory powers

56

. It relies mainly on data provided by national authorities, as it has

no powers of its own to inspect or gather information at source. The fact that Member

States have different surveillance and testing strategies made it difficult for the ECDC

to compare the epidemiological situation across the EU, an impediment which can

compromise the usefulness of its guidance.

55

Strategic and performance analysis of ECDC response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

56

Preamble (6) of Regulation (EC) No 851/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council

of 21 April 2004 establishing a European centre for disease prevention and control.

35

Member States applied uncoordinated approaches to COVID-19-related

internal border and travel restrictions

69 The national authorities’ implementation of the Commission’s guidance was

monitored in the ad hoc working group set up and led by the Commission: the Corona

Information Group (CIG). The Group aimed to identify problems and discuss them at a

technical level. The group met 33 times between February and September 2020.

70 All of the 33 meeting reports we reviewed clearly show that the Commission

made a significant effort to coordinate Member States’ actions. National

implementation of EU guidance was discussed at every meeting, with Member States

reporting on the measures they had taken. The Commission reiterated the overarching

principles of EU law, and emphasised the need for better coordination.

71 The CIG meeting reports and the public consultations for the Schengen Strategy

also show that the CIG was well regarded by the Member States. However, despite this

positive assessment, the CIG served mainly as a platform for exchanging information.

The Commission’s efforts to compensate for the lack of any crisis governance structure

by setting up the Group have not resulted in a consistent and coordinated approach to

internal border management by the Member States. This is evidenced by the different

approaches to COVID-19 internal border controls within the Schengen countries

(see Figure 3).

72 The meeting minutes we reviewed show that the Group also faced

communication challenges. Several Member States introduced new border controls

and travel restrictions without informing the other participants in the Group, even

though they had previously agreed to keep the other parties informed before

implementing any new measures.

73 We also analysed the documents mapping the situation at the internal borders

which the Commission produced in February, March and May (and partially updated in

June) 2021. Our analysis focused on the following four aspects: mandatory quarantine,

mandatory testing, entry and/or exit bans, and the use of ECDC maps for decision-

making. This served as a basis for a simplified overview, showing Member States’

measures over time (see Figure 8).

36

Figure 8 – Overview of travel restrictions among the EU-27 Member

States in the first half of 2021

N.B.: Due to the lack of readily available comparable data before February 2021, the figure does not

co

ver the travel restrictions put in place in 2020.

Source: ECA, based on the Commission’s internal monitoring of travel restrictions.

14 FEBRUARY

2021

18 MARCH

2021

28 MAY

2021

(partial update

on 8 June)

Mandatory quarantine upon arrival?

Mandatory testing upon arrival?

Entry and/or exit ban?

ECDC maps used for decision-making?

Yes, all arrivals

No

Yes, for public transport

Yes, for risk areas

Yes, if no test

Yes, all arrivals

No

Yes, for air travel

Yes, for risk areas

Yes, pre-departure test

Partial

No

Yes

Partially

No

Yes

37

74 In order to illustrate the challenges faced by EU citizens when travelling within

the EU, our analysis of minimum entry conditions on 21 June 2021 shows a wide

variety of practices put in place by Member States, ranging from quite open access to

quite restrictive measures (see Figure 9).

Figure 9 – Simplified overview of minimum entry conditions on

21.6.2021

Note: The figure shows minimum entry conditions for an EU citizen who was neither vaccinated nor

previously contaminated.

Source: ECA, based on the Commission’s internal monitoring of travel restrictions.

75 Figure 8 and Figure 9 show that despite the Commission’s efforts to facilitate

coordinated action, the travel restrictions imposed by Member States remained

uncoordinated, and formed a patchwork of individual measures that varied widely

from one Member State to another.

1

Member State

12 3 1 2 1 2 5

10 1 1 411

5 days 6 7 10 14

5 days

6 7 10 14

Free

entry

PCR test

Quarantine

(days)

No

entry

Travellers from

HIGH-risk areas

Travellers from

LOW-risk areas

38

Conclusions and recommendations

76 We conclude that while the Commission has monitored the free movement

restrictions imposed by the Member States during the COVID-19 pandemic, the

limitations of the legal framework hindered its supervisory role. Furthermore, the

Commission has not exercised proper scrutiny to ensure that internal border controls

complied with the Schengen legislation. Despite several relevant EU initiatives, the

Member States’ actions to fight COVID-19 remained mostly uncoordinated.

77 We found that the Member States’ notifications of internal border controls did

not provide sufficient evidence that the controls were a measure of last resort,

proportionate and of limited duration. However, the Commission has neither

requested additional information from the Member States, nor issued any opinion on

their notifications since the COVID-19 pandemic began. Furthermore, we identified

cases of border controls which had not been notified to the Commission. We believe

that this lack of essential information from the Member States has affected the

Commission’s ability to carry out a robust analysis of the extent to which the border

control measures complied with the Schengen legislation (see paragraphs 26-31

and 35-39).

78 Member States are required to submit an ex post report on the implementation

of temporary border controls, and to assess, among other aspects, how effective and

proportionate the reintroduction of border controls at internal borders has been.

Although nine Member States did not comply with the obligation to submit ex post

reports, we have not seen any evidence that the Commission asked the Member

States to provide the missing reports (see paragraphs 32 and 40-42).

79 Our review of all the ex post reports the Commission has received since 2020

shows that they vary greatly from general statements to detailed statistics. Ten out of

the 12 available reports did not cover the proportionality of applied measures in

sufficient detail. Only three reports briefly mentioned the possible use of alternative

measures (see paragraphs 41-42).

80 The Commission has the mandate and obligation to act in cases of potential non-

compliance. It can launch infringement procedures, but has not yet done so despite its

concerns that long-term internal border controls related to migration and security

threats do not comply with EU law. The Commission has instead opted for soft

measures and coordination with no apparent results, as the internal border controls

39

reintroduced more than six years ago are still in place. (see paragraphs 33-34

and 43-45).

Recommendation 1 – Exercise close scrutiny of internal border

controls

Taking account of the proposal to amend the Schengen Borders Code, and the

Commission’s scope for discretion, its assessment of internal border controls should

make proper use of the compliance monitoring tools by:

(a) asking the Member States for additional information when their notifications

and/or ex post reports do not provide sufficient evidence of the proportionality of

border controls;

(b) issuing opinions on proportionality when there are concerns that the border

controls do not observe this principle;

(c) systematically monitoring that all Schengen countries provide internal border

notifications and implementation reports within legal deadlines;

(d) asking Member States to report annually on the implementation of ongoing long-

term border controls; and

(e) launching enforcement action in the event of long-term non-compliance with the

Schengen legislation.

Target implementation date: end of 2023

81 The Member States implemented internal border controls to enforce a variety of

COVID-19 travel restrictions. Although the Commission is responsible for monitoring

whether these restrictions comply with the principle of free movement, we found that

the limitations of the legal framework hampered the Commission’s work in this area.

In addition, the length of legal proceedings, and the short-term and variable nature of

the measures which the Member States took during the pandemic, mean that the

infringement procedure, which is the only tool the Commission has to enforce the right

of free movement during the COVID-19 pandemic, is unsuitable (see

paragraphs 46-47).

82 Contrary to the case of internal border controls, the Member States were not

required to inform the Commission about travel restrictions. The Commission obtained

40

information from Member States, but it was not always complete or comparable.

(see paragraphs 48-49).

Recommendation 2 – Streamline data collection about travel

restrictions

The Commission should streamline information collection from Member States on the

justification for the proportionality and non-discrimination of their travel restrictions,

and provide guidance when this information is not sufficient.

Target implementation date: end of 2022

83 The Commission issued timely and relevant guidance to facilitate the

coordination of internal border controls. However, the guidance lacked practical

details about how Member States should demonstrate compliance with the principles

of proportionality and non-discrimination, as well as examples of good practice in the

way internal borders were managed during the pandemic. The Practical Handbook for

Border Guards, which serves as a user guide for border guards when carrying out their

border controls, has not been updated to take account of the pandemic (see

paragraphs 53-56).

Recommendation 3 – Provide more actionable guidance on the

implementation of internal border controls

The Commission should provide more detailed and actionable guidance on the

implementation of internal borders during the pandemic by:

(a) updating the Practical Border Handbook with examples of good practice of the

way internal borders are managed;

(b) explaining the difference between border controls and health checks in the

context of COVID-19.

Target implementation date: end of 2022

84 The Commission also launched important initiatives to coordinate measures

affecting freedom of movement. However, Member States’ practices show that, even

one year after the pandemic began, responses were still mostly uncoordinated and

were not always consistent with Commission guidance and Council recommendations

(see paragraphs 57-60 and 69-75).

41

85 The Commission set up a web platform to support the safe re-opening of travel