The University of Rhode Island

Master of Public Administration Program

University of Rhode Island,

Providence Campus

Providence, RI 02903

uri.edu/politicalscience/academics/m-p-a-program

Short-Term

Rentals in

Rhode Island

Prepared for:

Rhode Island

League of Cities

and Towns

1 State St # 502, Providence, RI 02908

Prepared by:

Master of Public Administration Policy Fellows,

Alice Aieskoll, Jake Clemen, Jenna Maloney,

Zachary Perkins

Faculty Supervisor:

Aaron Ley, Ph.D.

1

Executive Summary

This report was requested by the Rhode Island League of Cities and Towns with the overall aim of

creating a universal tool municipalities could use in managing short-term rentals (e.g., Airbnb,

Homeaway, etc). Upon studying the current environment for short-term rentals, the complexities

associated with the short-term rental marketplace became clear and made evident how such a tool does

not fit the current Rhode Island short-term rental economy. Instead, this report proposes policy options

for Rhode Island cities and towns to adopt after taking into account the unique context and

characteristics of each jurisdiction. The analysis included here examines the economic and social benefits

of short-term rentals while also providing policy recommendations to lower the potential drawbacks of a

burgeoning short-term rental market. The rise of short-term rentals presents new and complex policy

questions for state and local policymakers; the effective management of registration and enforcement,

taxation, nuisance considerations, and housing stock implications all merit consideration. Although

short-term rental properties are required to collect and remit taxes - similar to hotels - the process is

largely self-policed by the housing platforms themselves and the tax rates cannot be changed by

individual municipalities without General Assembly approval. The same statutes requiring General

Assembly approval for tax rate changes also prohibit municipalities from banning the listing of

short-term rental services by property owners, which means there are litigation risks associated with

these regulations. To address some of the drawbacks associated with short-term rentals, we recommend

the creation of regulations that deal with numerous issues concurrently rather than addressing each

potential issue individually. Residency restrictions (i.e. property operators must reside in property being

offered as short-term rental) and quantitative restrictions (e.g. maximum number of days a short-term

rental may be offered, maximum number of short-term rentals per municipality, etc.) each allow for

addressing both nuisance and housing stock concerns. Enforcement mechanisms we discuss include free

permitting, third-party monitoring, and direct municipal oversight.

2

Background

Introduction

A short-term rental (STR) is usually defined as a rental of a residential dwelling unit or accessory

building for periods of less than 30 consecutive days. In some communities, STR housing may be referred

to as vacation rentals, transient rentals, short-term vacation rentals, or resort dwelling units. STRs can be

owner-occupied or non owner-occupied dwellings and operators can rent out entire homes, apartments, or

rooms. Many STRs are advertised using online hosting platforms such as Airbnb, VRBO, and FlipKey.

These websites have created a surge in STRs, which are spread all over the country. The number of STRs

has grown at a 45 percent annual rate over the past five years and is expected to continue growing in the

foreseeable future (Host Compliance, 2018).

Rhode Island Context

Legislative history.

To regulate the STR industry, Rhode Island legislators introduced legislation in 2015 that

expanded the state’s hotel tax to include STRs of residential property, including the rental of vacation

homes and beach cottages. The bill was supported by Governor Gina Raimondo’s administration and the

Rhode Island Commerce Corporation. Proponents of the 2015 law projected that the collective 13 percent

tax would generate $7.1 million per year that could be used to support the state’s tourism sector (Parker,

2018). Rhode Island landlords, local and state property owner associations, and home sharing platforms

like Airbnb opposed the hotel tax. Landlords considered it inconvenient and predicted that it would

discourage property owners from renting properties (Shalvey, 2015). Despite opposition from this

coalition, the legislation passed on June 30, 2015, requiring STR operators to pay the state’s five percent

hotel tax for accommodations, including apartments, beach houses or cottages, condominiums, houses,

and mobile homes. The law requires 25 percent of the hotel tax to be allocated to the municipality in

which the STR or hotel

is located. In addition,

the 2015 legislation

also amended Chapter

42-63.1 of the Rhode

Island General Laws

entitled “Tourism and

Development” to

include a provision

preventing any city or

town from prohibiting

the listing of housing

units on STR platforms

by property owners

(Rhode Island

Department of Revenue, 2015).

In May 2018, the “Relating to Property - Short-Term Rentals Act” was considered but eventually

held for further study by the General Assembly as an amendment to Title 34 of the General Laws entitled

“Property.” The “Short-Term Rentals Act” amendment sought to clarify language that defined STR listing

services, STR providers, and STR transactions, in addition to addressing affordable housing concerns,

local control, safety and health, insurance, accessibility requirements, civil rights, posting of rates, and

3

penalty concerns for STR transactions. The proposal included an amendment to Title 34 of the General

Laws entitled “Property”, which addressed safety and health concerns while also defining safety and

health standards for STR operators. This includes safety and health standards that require operators to

maintain STR facilities in a sanitary condition while also meeting healthy and safety standards such as

installation of functioning extinguishers, smoke detectors, and carbon monoxide detectors. RI General

Law § 45-24.3-8 states an STR provider may not rent a unit to another person without first thoroughly

cleaning the unit and providing clean and sanitary sheets, towels, and pillowcases. In addition, the STR

facility shall have a clearly visible list of emergency information posted. While this particular act was not

passed, it does indicate that STRs and their impacts are still being considered and further legislation may

be proposed.

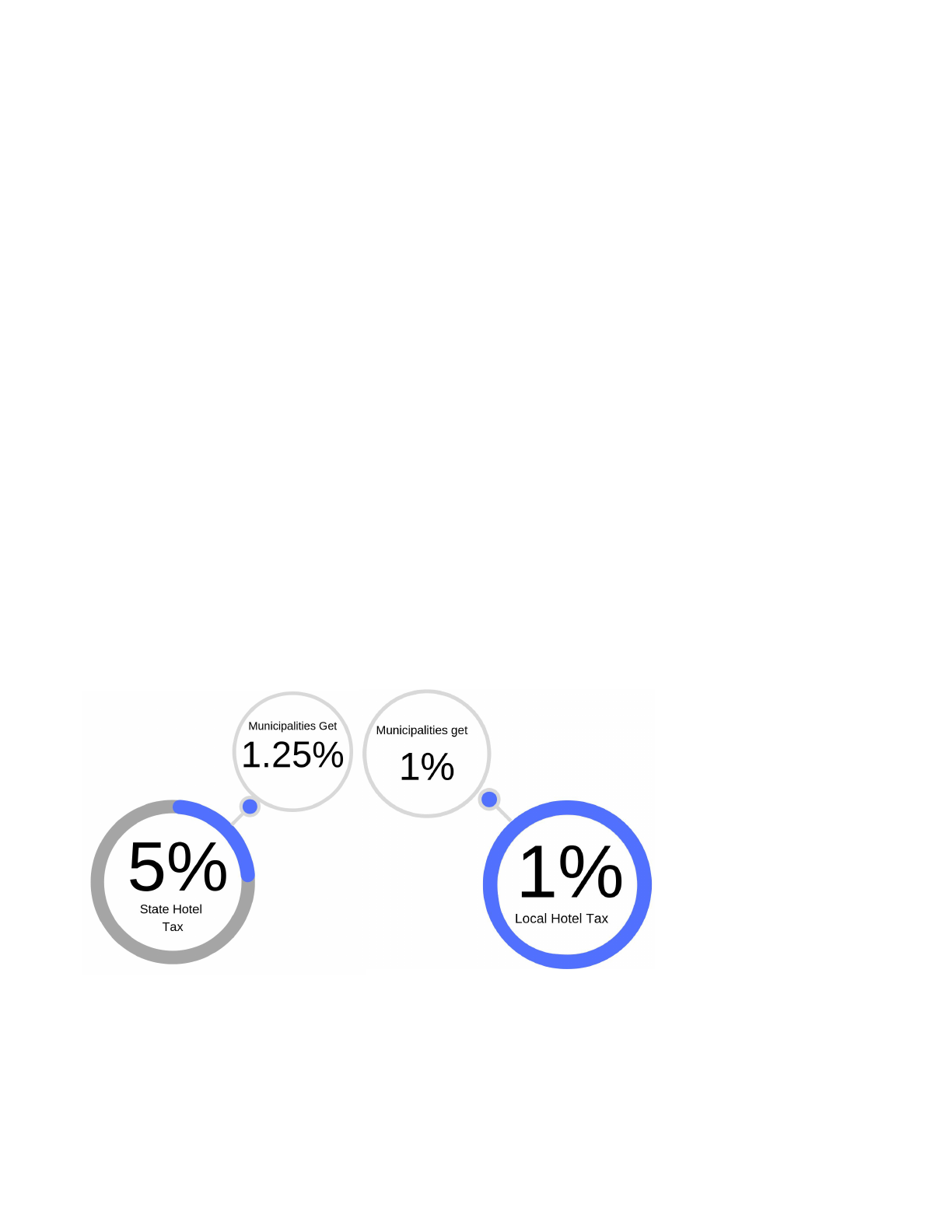

Current Rhode Island regulation - registration and taxation.

An STR is a rental property that is rented for no longer than 30 days. In Rhode Island, STR

operators must register with the Rhode Island Division of Taxation, pay the annual ten dollar sales tax

permit fee, and collect and remit the sales tax and the hotel tax if independently advertising STRs (i.e., not

through a hosting platform such as Airbnb). If an online platform is used, Rhode Island law requires the

hosting platforms to register with the state’s Division of Taxation, charge and collect the tax, and remit

the tax to the Division of Taxation (Rhode Island Department of Revenue, 2018). Registration requires

completing a business application either online or at the Division of

Taxation. For STRs of an entire house, entire condominium, entire

apartment, or other such residential dwelling, operators must collect

and remit the seven percent sales tax and the one percent local hotel

tax, for a total taxation rate of eight percent (the five percent statewide

hotel tax does not apply). For room rentals of 30 days or less, the seven

percent Rhode Island sales tax applies along with the one percent local

hotel tax and the five percent statewide hotel tax for a total taxation rate

of thirteen percent (Rhode Island Department of Revenue, 2018). The

one percent local hotel tax and 25 percent of the local share of the

state’s five percent tax was passed and was expected to generate

revenue of $10.0 million in FY 2018 and $10.9 million in FY 2019 for

distribution to cities and towns (RI Senate, 2018).

History of STRs and the Sharing Economy

The practice and culture of sharing has become so integrated with technology that it is now

referred to as the sharing economy. While the sharing economy traces its historical roots to colonial times,

its fusion with modern day technology has caused it to become more widespread through online STR

platforms like Airbnb (Jefferson-Jones, 2014). The growth of STR platforms has caused lawmakers to

begin addressing the potential social and economic consequences of STRs. These benefits include

allowing STR operators to efficiently utilize space in their homes while generating additional income, and

increasing economic activity and revenue in areas that are not normally visited by tourists. The benefits of

STRs, however, must be considered along with their potential downsides, which include their effect on

the local housing market and neighborhood complaints.

Community Impact

Neighborhood effects.

4

Residents in close proximity to STRs have complained about their effect on neighborhoods. STRs

are typically associated with noise and nuisance complaints created by unknown visitors. The negative

effects that are created include increased competition for parking spaces, increased traffic, and higher

usage of local neighborhood resources like community beaches. A perception also exists that transient

STR tenants care less for public and private spaces than permanent residents and have caused lasting

damage to surrounding areas (Edelman & Geradin, 2015). As a result of these nuisances, it has become

common practice for private condominiums and apartments to set their own rules regarding STRs so that

some buildings allow them, while others do not (Edelman & Geradin, 2015). STRs have also been found

to reduce the amount of affordable housing stock (Gurran & Phibbs, 2017). If properties are bought and

used for the primary purpose of being rented out as STRs, the properties become no longer available as a

long-term housing option. One study of STRs in Los Angeles found that STRs cause gentrification in

surrounding communities, reduce socioeconomic integration, and exacerbate racial and socioeconomic

inequality (Lee, 2016).

Economic Impact

Impact on the housing market.

There is an existing debate as to whether or not STRs increase housing costs, or if they allow low

income property owners to acquire and save money to offset the costs of homeownership (Kaplan &

Nadler, 2015). For some homeowners, STR arrangements increase home and neighborhood property

values (Jefferson-Jones, 2015). The income that is added through STRs allow homeowners to pay off

mortgages earlier, while also allowing them to finance improvements to their properties that attract STR

customers and improve the desirability of the community (Lee, 2016). STRs also distribute housing

resources more efficiently, where bedrooms which

may have otherwise been unoccupied can be used

(Palombo, 2015). Kaplan and Nader (2015) found

that fewer than two percent of users have three or

more listings, suggesting that very few users are

listing at a commercial level. STRs are dispersed

around wide areas, but demand is not as high for

those far from city centers (Quattrone et al., 2016).

Consequently, there will be greater effects on the

housing market in areas with higher population

density as STR transactions increase the

prevalence of frequent short-term renters and

reduce the supply of properties to be otherwise

used for long-term residents (Lee, 2016). Cities

and towns have responded to the negative effect of STRs on local housing markets in different ways. For

example, San Francisco has taken a strong regulatory approach and requires rental operators to obtain

permits, which are only granted to homeowners with a regular presence on the property. A similar

regulation was passed in Boston to prevent STRs from removing affordable housing stock from the

market.

5

Impact on the hotel industry.

Researchers have argued that STRs are a form of disruptive innovation that will harm the hotel

industry (Guttentag, 2015). Disruptive innovation theory describes how products can, over time,

transform a market and capture mainstream consumers. The improvement of the disruptive product

eventually causes it to become more appealing to customers and thus significantly impacts existing

businesses. Airbnb, for instance, has grown to be the largest home sharing enterprise in the world, having

hosted more than 60 million guests to date (Horn & Merante, 2017). Its rapid popularity has sparked

concern over whether STRs threaten the traditional accommodation sector. Some researchers have

discovered that the number of Airbnb listings negatively affects hotel revenue in regions where both exist,

particularly low-end hotels without conference spaces (Oskam & Boswijk, 2016). In one Texas market,

every one percent increase of new Airbnb listings caused a .05 percent drop in hotel industry revenue

(Kaplan & Nadler, 2015). An additional study strongly suggests that Airbnb provides a viable, but

imperfect, alternative for certain types of overnight accommodation. Lower-end hotels and hotels not

catering to business travelers are highly vulnerable to increased competition from rentals enabled by firms

like Airbnb (Zervas, Proserpio and Byers, 2017). Another analysis demonstrated how some hosts signaled

a preference or expectation for guests of lower income levels by self-identifying the service as a low-cost

option targeted toward frugal and less discerning guests (Lutz & Newland, 2017). Studies also

demonstrate that STRs minimally impact the hotel industry and that hotels are beginning to list vacancies

on STR platforms (Edelman & Geradin, 2015).

Economic development.

STR platforms utilize real-time market conditions to deliver efficiencies in pricing. Airbnb was

designed to address the influx of prices caused by high-demand events like conferences (Edelman &

Geradin, 2015). Research shows that Airbnb guests tend to stay an average of two days longer than

typical hotel guests (Kaplan & Nadler, 2015). During 2012-2013 alone, Airbnb guests spent $632 million

in New York City and supported over 4,000 jobs. Furthermore, Airbnb argues that its offerings expand

tourism to areas at such a rate that hotels benefit from the increased overall market demand for

accommodations (Boswijk, 2016). Moreover, STRs provide market segment fulfillment for consumers

seeking sharing (particularly of a home), practical novelty, and interaction novelty, which further supports

increased tourism in a way that hotels cannot (Guttentag, 2016). The income effect is also significant and

positive, demonstrating that guests higher in socioeconomic status are more likely to book an entire home

than consumers of lower socioeconomic status, providing further market segment fulfillment by drawing

in customers that are not attracted by hotels (Lutz & Newlands, 2017).

The capacity for individual residences in neighborhoods to offer one or more rooms via STR

platforms carries substantial potential financial benefits to homeowners in particular and the

neighborhood at large (Palombo, 2015). Airbnb contends that STR platforms and home sharing allows

visitors to stay longer, spend more money, and provide more income to the local community (Boswijk,

2016). In an Oregon study, some cities indicated that STRs provide new tax revenues and support for

tourism by providing additional lodging options and, thus, drawing tourists into areas they might not have

otherwise visited (DiNatale, Lewis & Parker, 2017). STRs also keep guests away from centrally located

hotels, which provides an opportunity for additional neighborhood improvement via homeowner revenue

increases (Kaplan & Nadler, 2015). The neighborhood improvement may also come via the shared city

initiative where owners of Airbnb properties can donate part of each stay toward supporting

community-based activities (Palombo, 2015).

6

Regulatory Implications

STRs blur the distinction between commercial and residential activity, which makes applying

municipal land-use regulations difficult (Gurran & Phibbs, 2017). Cities seek to stimulate the positive

economic effects of STRs for the tourism industry, local entrepreneurs, and its hosts while minimizing

two negative effects that rank high among the concerns of residents: (1) the shortage of affordable

housing and (2) neighborhood changes (Nieuwland & Van Melik, 2018). Nieuwland and Van Melik

(2018) published a study where they found three general regulatory approaches to STRs – prohibition,

laissez-faire, and allowing STRs with certain restrictions. The first approach bans STRs altogether in an

entire community or certain district. Although this approach countered the negative effects of STRs, local

governments sacrificed tax revenues and added homeowner income, while also creating an underground

market for STRs (Nieuwland & Van Melik, 2018). The laissez-faire approach prescribes not interfering

with the industry and proposes no regulatory options. The most commonly adopted approach is the third

one, which permits STRs with restrictions.

Numerous regulatory options exist under this third option, including an STR permitting process

limiting the amount of permits per neighborhood (or square mile), prohibiting “conversion” by stopping

landlords with no-fault evictions from listing as STRs for one year, and allowing STRs only in buildings

that meet an inclusionary housing threshold where a certain percentage of the units in the building are

deemed affordable long-term housing (Lee, 2016). Nieuwland and Van Melik (2018) identify the

following as the four overall types of restrictions: quantitative restrictions limiting the amount of STRs,

the number of visitors, the number of days, and the number of times an Airbnb can be rented out per year;

locational restrictions confining STRs to certain locations; density restrictions limiting the number of

STRs in certain neighborhoods; and lastly, qualitative restrictions limiting STRs by defined type of

accommodation (i.e., complete apartment, room, commercial-style Airbnb, etc.).

7

Problem Identification and Policy Alternatives

Nuisance

This section of our policy analysis will focus on the problems that arise when STRs become more

prevalent in communities. The most common complaints that occur involve nuisance behavior, such as

loud noise, increased trash, parking issues, and additional traffic. Neighbors in proximity to STRs have

complained of late night check-ins, loud music and backyard gatherings after bar hours, the late night use

of outdoor hot tubs, marijuana smoke, and loud profanity (Weisburg, 2016). Residents have also voiced

concerns about neighborhood preservation as transient visitors have become more prevalent in

neighborhoods. Permanent residents argue that short-term tenants are without ties to the neighborhood

and therefore do not reflect the community’s values (Jefferson-Jones, 2015). Local residents also argue

that residential areas are not zoned for lodging purposes. Although hosting platforms claim that these

types of complaints are uncommon, nuisance behavior is a very real issue for local residents living near

STR properties. For Rhode Island communities confronting issues relating to nuisances, we have explored

several alternative policy responses that may be available to them. They include the following:

Alternative 1: Require renters to agree to “house policies.”

One approach to handling nuisance behavior is to require renters to agree to “house policies.” In

Miami, rental operators must provide written notice to transient occupants of vacation rental standards

and regulations for noise, public nuisance, parking, solid waste collection, and common area usage

(Miami-Dade County, 2018). Similarly, in Maui, rental operators are required to post house policies,

which must be signed by renters. House policies in Maui must include quiet hours from 9:00 p.m. to 8:00

a.m., during which time the noise from STRs shall not unreasonably disturb adjacent neighbors. Sound

that is audible beyond the property boundaries during non-quiet hours shall not be more excessive than

would be otherwise associated with a residential area. Maui County also requires rules on parking and

group gatherings to be included in STR house policies. Vehicles must be parked in designated onsite

parking areas and they are not to be parked on the street. Finally, the policy associated with the property

must state that no parties or group gatherings other than registered guests shall occur (Code of the County

of Maui, Hawaii. Title 19, Article IV., Chapter 19.65). One clear benefit of considering the posting of

house rules as a regulatory alternative is that there is minimal financial cost related to posting written

rules. One downside, however, is that it will be difficult to these rules without and enforcement

mechanism that requires routine inspections and the imposing of fines, which will be discussed later in

this section.

Alternative 2: Financial penalties.

In response to neighborhood nuisance, cities and towns can impose fines on the offending STR

operator or on property renters. Under this type of response, STR operators are responsible for having

written rules in place regarding noise, trash, and parking, while also notifying renters of fines associated

with noncompliance. Written notice would be necessary to ensure renters are aware of STR policies and

will have an opportunity to abide by them. A positive aspect of this option is that it carries with it a

deterrent effect, which may stop unwanted nuisances from occurring in the first place. High fines levied

on property owners for a guest’s nuisance behavior may give hosts a stronger financial incentive to

require more respectful behavior from guests or to carefully examine the background of guests renting the

property. Another option is to place the burden of compliance on the renters. A major financial incentive

8

exists for renters to comply with nuisance rules and regulations, because so many of them are motivated

by the financial savings associated with STRs. Fines can also be used to fund resources that help ensure

greater STR regulatory compliance, such as hiring a municipal employee responsible for enforcing the

local STR laws. One downside to this alternative is that imposing high fines may ultimately deter STR

operators from renting their properties, which may lower the number of available STR properties.

Alternative 3: Require STRs to be owner-occupied.

Requiring primary residence is not an uncommon response for addressing STR issues. This action

prevents commercial operators (those who rent three or more properties) from large-scale renting. The

City of San Francisco allows a host to register his or her primary residence only, defined as the place

where the host resides 275 calendar days per year (San Francisco Office of Short-term Rentals, 2018). For

275 calendar days, the property will not be used as an STR as it will be used as a primary residence.

Without this restriction, a property can be used as an STR every day of the year. Since this regulation

limits the amount of time a property can be used as an STR, opportunities to generate nuisances are fewer.

Boston is another city that requires tenants and investors to occupy their rental units in order to list

properties as STRs. One downside to this approach is that it will be met with fierce criticism or possible

lawsuits from commercial operators and owners who have purchased property for the sole purpose of

using them as STRs. The benefit of this option is that requiring operators to claim primary residence of

their properties may encourage the rentals to become long-term rentals that add to the available housing

stock. San Francisco and Boston are cities with housing shortage concerns, so this type of regulation is a

particularly beneficial way to respond to this problem.

Alternative 4: Frequency restrictions.

Another way to address nuisance behavior is to limit the number of days renting can occur on

STR properties. San Francisco limits rentals to a maximum of 90 days per year when the host is not

present in the unit. Property owners violating the ordinance are fined $484 for the first offense and up to

$968 for repeat offenses (San Francisco Office of Short-term Rentals, 2018). Similarly, in London, a

property can be used as an STR for a maximum of 90 days per year. The downside of this approach is that

it restricts the way owners can use their property and will cause opposition from STR operators.

Moreover, enforcement of this regulation poses its own challenges in that it will require municipalities to

develop systems that monitor the number of days STR properties are being used as rentals. San Francisco

is one of the only cities with an Office of Short-term Rentals to handle all STR matters. As we will

discuss in a later section, creating a separate office to respond to STR matters is costly because it involves

staffing and financing a new organizational unit.

Alternative 5: Restrict occupancy.

Another way to limit nuisance complaints is to place limits on the number of occupants allowed

per household or per room. This alternative is aimed at preventing loud parties on STR properties. In

Miami, the maximum overnight occupancy is two people per bedroom, plus two additional people per

property, up to a maximum of 12 people, excluding children under three. In Maui, guests must agree to a

policy of no parties or group gatherings. The downside of this alternative is that it limits the number of

people and, thus, limits the potential for additional local revenue by placing limits on occupancy.

Allowing more people into cities and towns allows visitors to spend money in restaurants and bars, movie

9

theaters, and other locations. Another shortcoming is that regulation would be difficult as there is no way

to ensure compliance from renters because STR renters can secretly invite additional guests to the

property without the property owner’s knowledge. Furthermore, limiting the number of guests does not

promise that noise will be abated because noise can be generated by any group, no matter how small. The

benefit of this alternative is that it minimizes nuisance behavior by restricting parties and minimizes the

potential for noise and neighborhood nuisance.

Housing Stock

The effect on housing stock is another common issue arising with the growth of STRs in

communities. In this section we focus on several emerging issues regarding both documented and

anticipated STR impacts on housing stock. The two main issues relating to housing stock that we

analyzed for this report include hotelization and low- and moderate-income housing impact. An analysis

of these impacts on RI municipalities and our associated recommendations follow.

Hotelization.

Hotelization occurs when property owners convert housing units from long-term rentals to STRs

with the aim of making more money. These property owners usually have more than one listing on STR

platforms, with two listings being the most common. Property owners with three or more listings are

considered to be commercial operators, which make up only three percent of Airbnb property owners

nationally (Kaplan and Nadler, 2015). Both of these aforementioned instances - two property listings by

one owner and three or more listings by another owner - remove long-term housing from the market.

Kaplan and Nadler (2015) identify a more malicious form of hotelization where landlords of large

apartment complexes pursue no-fault evictions of tenants in order to turn their complexes into more

profitable large-scale STR's. Abcarian (2015) interviewed one tenant from San Francisco who was not

allowed to renew her long-term lease, which was then listed as an STR for $250 per night. Higher rates of

10

hotelization not only lead to reductions in long-term housing, but also cause an increase in the cost of

existing long-term housing.

In November of 2018, there were a total of 2,758 Airbnb listings in Rhode Island, of which 936,

or 33 percent, are hosted by commercial operators (InsideAirbnb.com, 2018). Of those listing STRs in

1

Rhode Island, 169 are commercial operators, comprising 18 percent of all operators in the state. As such,

Rhode Island’s ratio of commercial Airbnb operators to total operators may be six times greater than the

national average. While many of these commercial operators list standard names like “Cindy” or “Mike,”

several more are listed under names that indicate they are without question commercial operations. These

include “Evolve Vacation Rentals” with 26 unique listings, “AMPM Property Management” with 13

unique listings, and “Atlantic Beach Hospitality” with 13 unique listings. Overall, 71 percent of Rhode

Island Airbnb listings are whole home rentals and 29 percent are room rentals according to the

InsideAirbnb data(2018). In comparison, commercial operators in the state offer 60 percent of their

listings as whole home rentals and 40 percent as room rentals (InsideAirbnb.com, 2018). This

demonstrates that commercial operators tend to operate both types of STRs - whole home and room

rentals - in contrast to some of the national data mentioned above. As a means of preventing hotelization

from reducing long-term rental stock, three primary regulations can be imposed: tiered fee structures, time

limitations, and owner residency restrictions.

Alternative 1: Tiered fee structure.

One way of addressing the issue of hotelization of STRs is by adopting a tiered registration fee

structure. This fee structure progressively increases the cost of offering an STR based upon the number of

STRs a single operator runs. Portland, Maine has adopted such a system where operators renting property

for less than 30 days must register with the city for $100 annually if listing a single unit. For two units in

the same building the fee increases to $250, which increases to $2,000 for five units. For non-owner

occupied rentals, a one unit fee is $200 with the fee increasing to $4,000 for those operating five units or

more. Discounts are applied for prohibiting smoking, installing sprinkler systems, or having fire alarms

that are connected to local fire departments. A $1,000 penalty is fined for providing false information on

the registration form (portlandmaine.gov, 2018). One of the key benefits of a tiered STR fee structure is

that municipalities can even the playing field between high volume commercial operators and low volume

operators, while also keeping incentives in place to discourage the removal of long-term housing. The

primary costs of this fee structure are those associated with developing and enforcing a registration

process, as well as forgoing the taxes associated with increased STR offerings brought by commercial

operators.

Alternative 2: Frequency restrictions.

Frequency restrictions limit the number of days a specific unit is listed on an STR platform.

Several options are available for this type of frequency restriction: days per year, days per month, months

per year, etc. Rhode Island municipalities near beaches, for instance, may choose to implement frequency

restrictions that allow STR listings only during the months of June, July, and August. With South County

being a primary housing location for academic-year undergraduate and graduate students from the

1

This data, as well as all other RI data in this section, is a result of analysis that took place in November 2018. InsideAirbnb data is a snapshot of

a moment in time and is the main source of data for several other academic studies (see Gutiérrez et al., 2016; Kakar, Franco, Voelz, & Wu,

2016) on STRs despite its limitations.

11

University of Rhode Island (URI), restricting STRs to the summer ensures long-term rental availability,

while also providing property owners with the best period of the year to offer STRs in a high tourism

region. One benefit of this alternative is that it provides greater certainty in preventing the prevalence and

growth of commercial operators from reducing long-term housing availability. Although the benefit is

more certain, the downside is more pronounced, as well: only allowing STRs for a limited number of days

stops property owners from collecting revenue that is earmarked for making improvements to their

property.

Alternative 3: Require STRs to be owner-occupied.

An owner residency restriction limits eligibility for STR listings in a particular municipality to

just those property owners who reside on the premises of the STR offering. Currently, Boston allows

STRs to operate only if they are owner-occupied units (Sokolowsky, 2018), meaning that hotelization is

effectively illegal. It is important to note that this option is currently the subject of an Airbnb lawsuit

against the city of Boston (Associated Press, 2018). Although this would be a guaranteed means of

eliminating hotelization, for some municipalities litigation of this nature may be cost-prohibitive and has

substantial potential cost downsides should an STR platform file suit like in Boston.

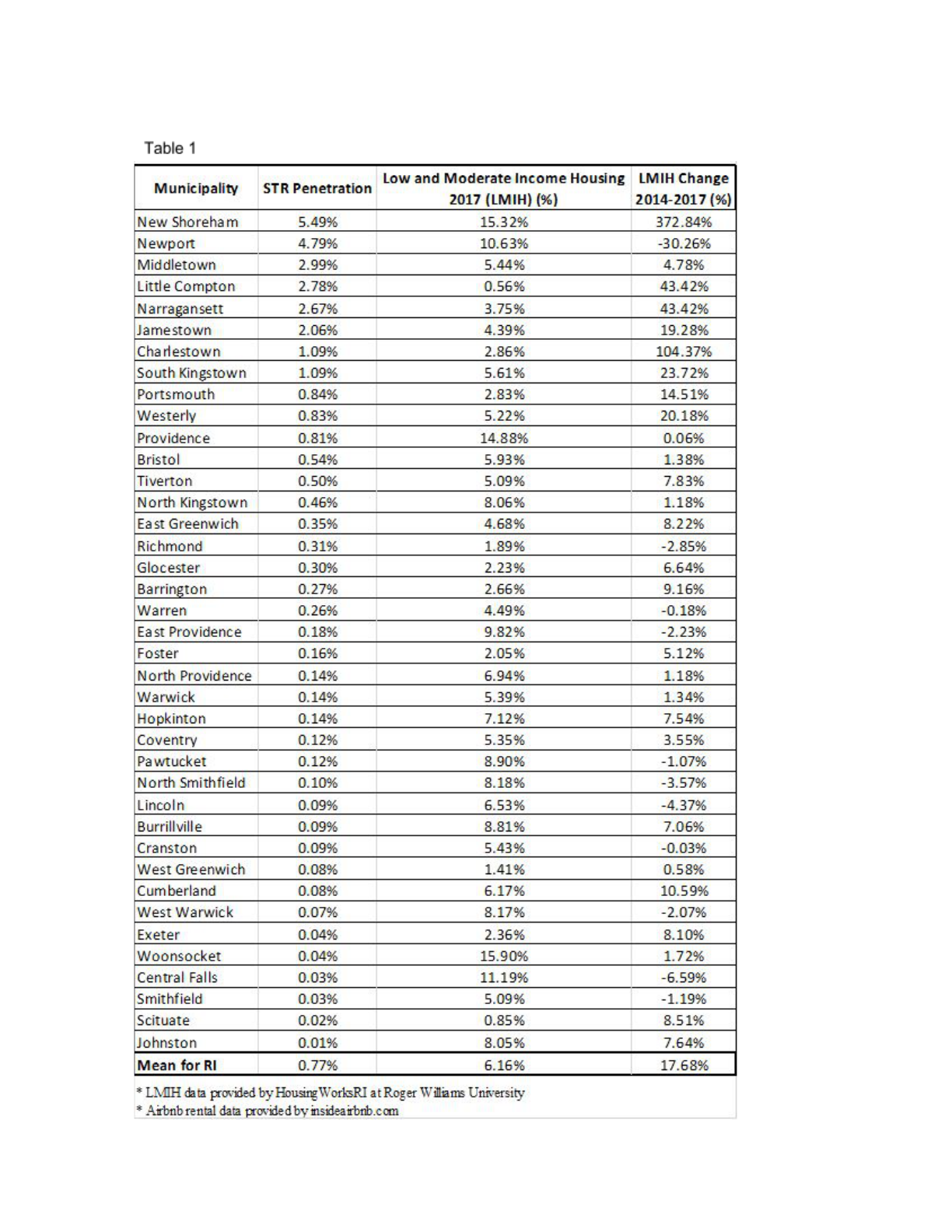

STR market penetration and low and moderate income housing (LMIH).

Decreased low and moderate income housing availability is perhaps one of the most

consequential documented effects of STR prevalence in municipalities. LMIH is also cited as a building

block for effective community economic development and facilitating economic growth (Wardrip,

Williams, & Hague, 2011; Klacik, 2003). In 2004, the RI General Assembly passed the Low and

Moderate Income Housing Act to address this issue. That law recommends that municipalities have at

least ten percent of their housing units categorized as LMIH (RIGL 45-53-2). To date, only five

municipalities have accomplished this target for affordable housing and so it is important to take into

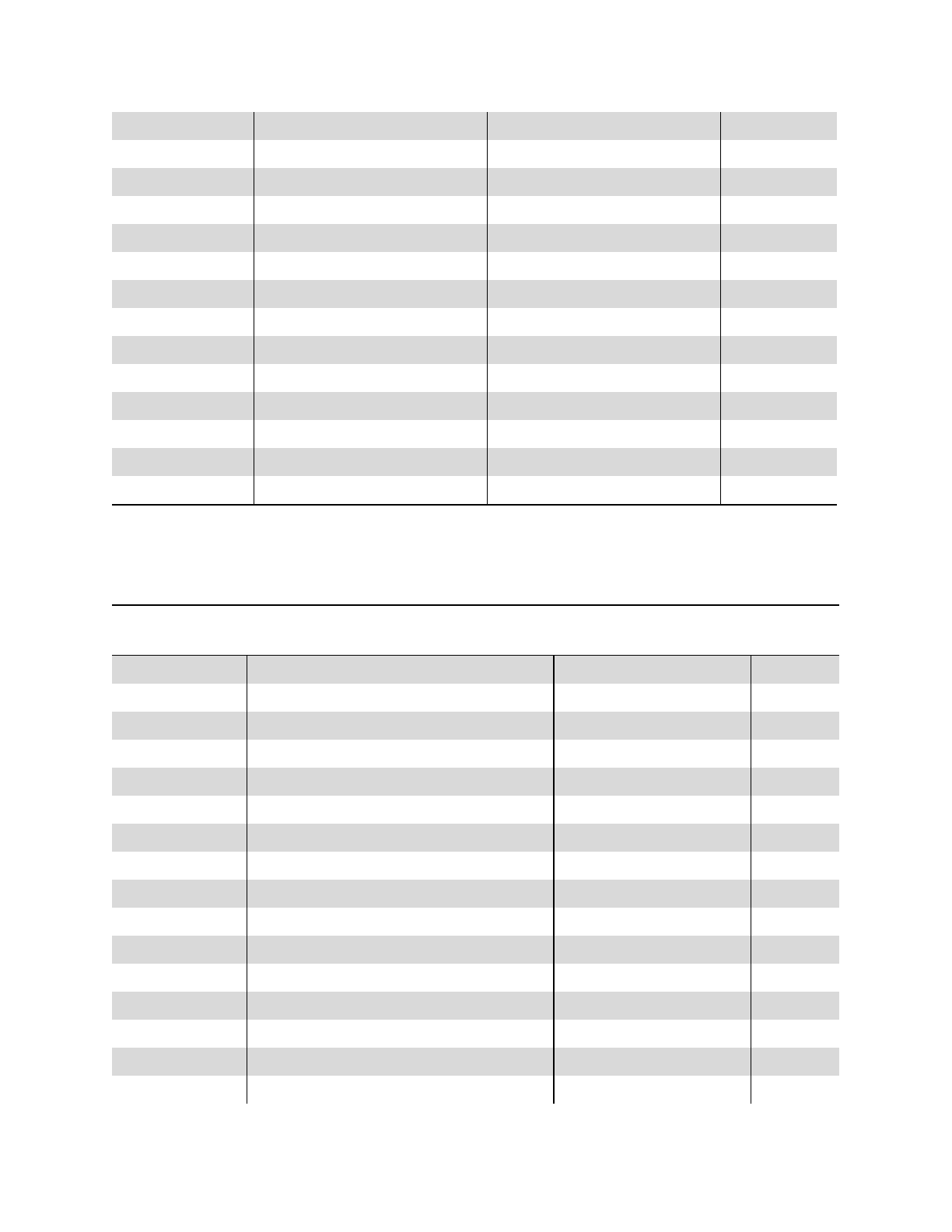

consideration the current state of LMIH in Rhode Island. Table 1 demonstrates market penetration of

STRs in all 39 municipalities along with the percentage of all housing in each municipality categorized

2

as LMIH and the change in LMIH from 2014-2017:

2

STR penetration in the housing market is calculated by taking the number of residential properties offering STRs

and dividing this by the total number of housing units in a particular municipality

12

13

Due to RI state government attempting to influence an increase in LMIH (reflected in an average

municipal LMIH increase of 17% across the state) and a burgeoning STR market that is demonstrating

growth, there is substantial potential for overlap wherein STR offerings replace LMIH. Given that the vast

majority of municipalities in the state do not provide the statutorily recommended minimum amount of

LMIH, several regulatory options exist for municipalities to consider: quantitative restrictions, qualitative

restrictions, and time-horizon restrictions.

Alternative 1: Quantitative restrictions.

Quantitative restrictions allow STRs only insofar as a certain proportion of all community

housing is already designated and available for low and moderate income persons (e.g., ten percent as

statutorily recommended). This could be broken down by building, neighborhood, or by taking the LMIH

proportion of the municipality as a whole. By ensuring a ready supply of LMIH through a quantitative

restriction of STRs, it is possible that lower income persons will have access to affordable dwellings. The

feasibility of these regulations hinge on a permitting or licensing process that is in place, as well as

adequate tracking of the LMIH proportion of total housing. With this information available, a

municipality can restrict new permits from being issued whenever that municipality’s annual LMIH data

indicates it is not meeting the state statutory recommendation of ten percent.

Another option for quantitative restrictions would be to restrict the number of STR permits or

licenses made available through the municipality. This could be done in absolute terms or in proportion to

property demographic changes. For example, a municipality of 2,000 households allows permits for 50

STR properties. Or if 40 new houses are built in a municipality, STR permitting can be expanded by one

for the following year (maintaining a 2.5% STR penetration rate). By capping the number of STRs, a

municipality can quickly control potential LMIH effects from the growing STR market. The most notable

downside to all these quantitative restrictions is the capacity required for enforcement and the capping of

permits, the loss of tax revenue from not allowing more aggressive STR expansion, and the loss of

revenue to property owners.

Alternative 2: Operational restrictions.

Operational restrictions differ from quantitative restrictions in that no limitations are placed on

whether

somebody may offer his or her property as an STR. Rather, operational restrictions limit how

much

of a property can be offered for rent or how often

that property can be rented. The latter portion is

akin to the frequency restrictions noted in the hotelization section. As such, these restrictions limit either

the number of rooms that are allowed to be rented per property or the number of times a property is

allowed to be rented (per week, per month, etc.). With a system like this being such a complicated

undertaking, the primary cost to the municipality of pursuing this type of restriction would be the ongoing

collaboration and tracking, along with Airbnb and other rental services, of how often a particular property

is rented. The primary benefit of this alternative is that it allows earnings from STR listings, organic

growth in property owners that list as STRs, and the preservation of some housing stock for LMIH.

Moreover, this alternative also decreases the potential for nuisance issues as noted in the nuisance section

of this report.

Alternative 3: Proximity restrictions.

14

A proximity regulation requires a tracking process, like the permitting and licensing identified

with quantitative regulations. However, unlike quantitative restrictions, proximity regulations restrict new

STRs from being located within a certain distance of already existing ones. Although this requires

substantial public education on the part of the municipality, it allows a more fine-tuned approach to

addressing the neighborhood LMIH impacts of STRs. This regulation enables a municipality to ensure

STRs are spread throughout the various locales of a particular neighborhood which, in turn, better ensures

that LMIH stock can be available throughout the various locales of particular neighborhoods. The primary

downside of this alternative is the substantial investment required by a municipality in determining the

optimal proximity restriction (e.g. 500 ft, 2 blocks, distance varying by population density, etc.) and

utilizing geographical information systems to maintain an accurate database of active STRs that are

licensed and permitted.

Enforcement

Municipalities have adopted a variety of different regulatory measures like those above. We have

concluded that enforcement of any alternative that is adopted will pose significant challenges for

communities addressing the issue of STRs. Lack of regulatory enforcement allows STR operators to

violate municipal ordinances, zoning codes, and required registration procedures without consequence.

Hawaii dealt with this issue when STR platforms were not required to register nor comply with STR tax

laws. According to Ross Birch, the Executive Director of the Island of Hawaii Visitors Bureau, less than

25 percent of Airbnb and VRBO operators are registered and paying taxes. A total of 2,034 operators are

registered compared with 8,647 STR listings (Lauer, 2018). Airbnb does not collect or remit taxes in

Hawaii, but legislation is pending that requires software platforms to submit them (Sokolowsky, 2018).

Two different lodging standards exist in Rhode Island, one for licensed and inspected hotels and inns, and

the other for STR properties, which are not licensed or inspected. This raises questions as to how

municipalities should identify STR properties and formulate an equitable approach to regulating them

(Bridges, 2018). To comply with the state’s Short-Term Rentals Act, enforcement agents, whether as

private contractors or municipal employees, should be charged with ensuring that safety and health

15

requirements are being met. The following alternatives represent some strategies for ensuring better

enforcement of STR regulations.

Alternative 1: Free permitting and permit display.

Nguyen, Taheri, and Valenta (2016) analyzed STR permitting in Los Angeles and recommend

creating a system with free permitting that requires STR permit numbers to be displayed on any

advertisement. The authors argued that compliance under such a system will increase because it will be

easier to identify operators that are not in compliance with STR policies. STR platforms have resisted

complying with these ordinances, causing some municipalities like Portland to take legal action against

platforms that do not require users to register with municipalities before using the platform (Njus, 2018).

In Portland, Airbnb, for its part, has aided in enforcement by removing ads not displaying permit numbers

(Nguyen et al., 2016). Making the permitting process available through an automated online platform and

at no cost expedites the process and encourages compliance from those not earning large sums of money

through STR rentals (Nguyen et al., 2016). Nguyen et al. (2016) also suggest that municipal workers can

easily find STRs not complying with local regulations because the permit number will not be displayed

with advertisements. While most of these regulations refer to displaying the permit number in an

advertisement, in New Hampshire STRs also have to display their physical permit in a visible window.

Municipalities could choose to require the permit number to be posted on advertisements and a copy

posted at the physical location. It is important to note that this enforcement mechanism has caused

litigation between platforms and municipalities elsewhere, while also adding to a municipality’s

responsibilities by requiring the creation of an online permitting system that employees will review for

compliance.

Alternative 2: Third party compliance monitoring.

Municipalities can outsource enforcement efforts by contracting a third party company to review

STR locations and activity. In Newport, city records indicated 198 registered STRs, but Airbnb notified

Newport that they had 390 active hosts that accommodated 22,000 guest arrivals staying at an average of

two nights per month (Rulli, 2018) In response, Newport hired a private company, Host Compliance, to

identify the registered establishments within the municipality. The price of contracting with Host

Compliance, LLC depends on the number of STRs within a municipality and the type of monitoring

services purchased. In 2017, the City of Newport paid $29,980 for this service as a way of monitoring

STR identification and compliance. One benefit of partnering with a third party service provider is that

monitoring begins quickly and there is no need for designing and executing a municipal personnel

training system. The costs associated with contracting third party compliance monitoring results in

reduced municipal control and oversight of STR activity. However, depending on the level of STR

activity within a municipality, contracting out for compliance monitoring could be a better option than

hiring a municipal officer. In some municipalities, STR activity may be too low to provide a return on

investment for contracting out for STR services.

Alternative 3: Municipal oversight and control.

The Newport Planning Board’s STRs investigative task force recommended the hiring of an STR

officer for municipalities dealing with STR issues. An officer hired for this position collects registration

forms and fees, works with state and local tax offices to collect revenues, and identifies illegal guest

16

houses by reviewing hosting platforms (Flynn, 2017). Allocating funding to support a monitoring agency

will require considering how the agency will be funded in the municipal budget. For example, in the

FY2018 budget, the City of Newport allocated $1,568,921 and expended $1,576,243 in police salaries, as

well as $22,479 in direct enforcement, with overtime totaling $75,000 as expended. In addition, the City

of Newport expended $456,000 dollars in FY2017 to support personnel in planning and zoning

enforcement (City of Newport, 2018). The City of Newport’s Planning Board supports increasing the

STR registration fee over the current amount of $45 in order to help defray personnel costs and to

increase the municipality’s monitoring and enforcement capacity. At the current registration fee of $45,

registration user fees can generate revenue for the municipality should all STR operators register their

STR units. For example, for the 12 months leading up to July in 2018, Newport had 708 active whole

home rentals (Flynn, 2018), which generated $31,860 in revenue for whole home rental registration.

Within the same time frame, Newport had 462 rooms available for rent, with only 16.16 percent rooms

registered. Ensuring that all STR room operators register their STR units would yield $20,790 in revenue

based on registration fees for Newport (Flynn, 2018). The Short Term Rentals Investigatory Group

recommended that the $45 registration fee for Newport could be increased substantially; allowing for

increased revenue for the municipality to further support personnel costs while adding greater capacity to

monitor regulatory compliance (Flynn, 2018). The task force recommended hiring a municipal

administrator responsible for enforcement of registration requirements and administering fines set at a

minimum of $1,000 for listing unregistered STR units online. Any revenue generated would then be

redirected to the Town’s restricted funds to continue supporting personnel costs to administer STR

monitoring compliance. For owners who continue to advertise illegally or rent without registering their

STRs, the task force also recommended that fines should increase for owners (Flynn, 2018).

Municipal control may also become burdensome over time, especially as STR numbers increase

substantially. Municipalities may not be able to commit the necessary resources and support in the

oversight process. Municipalities also do not know the future of the STR market, and committing

permanent resources and personnel to enforcement may be a poor investment. Platforms like Airbnb have

been fairly good at complying with regulations but have certainly not gone out of their way to help

municipalities with enforcement, and these platforms value the privacy of operators. Overall, municipal

oversight may be infeasible for smaller municipalities and unwieldy for larger ones, but it provides total

control over STR enforcement.

17

Rhode Island Tax Implications

Current STR Tax

The State of Rhode Island currently taxes STR operators by varied amounts depending on the

type of STR dwelling, with funds being collected and distributed in different ways. An entire house,

cottage, condo, or apartment is taxed at a seven percent sales tax rate and a one percent local hotel tax rate

(totaling eight percent). The seven percent state sales tax is allocated to the state’s general fund while the

one percent rate is distributed to municipalities. Short-term room rentals are taxed an additional five

percent, which is the state hotel tax (for a total taxation rate of thirteen percent). The funds from this state

tax are distributed to municipalities, the RI Commerce Corporation, regional tourism councils, the

Providence/Warwick Convention & Visitors Bureau, and East Providence escrow. According to data from

Inside Airbnb (2018) about 70 percent of Airbnb rentals are whole home rentals, while 100 percent of

VRBO and HomeAway rentals are whole properties. This makes approximately 30 percent of STRs

subject to the state hotel tax. State law precludes municipalities from creating their own taxes on STRs as

stated in RIGL § 42-63.1-8.

Municipal Tax Revenue from STRs

Tax

Whole Home

Room Rental

Local Hotel Tax

1%

1%

State Hotel Tax

N/A

1.25%*

Totals

1%

2.25%

*Municipalities get 25 percent of the five percent State Hotel Tax

Municipal Income

Municipalities receive one-fourth of all

revenue from the five percent state hotel tax. The RI

Division of Taxation collects the tax and then

distributes it to the municipality. The RI Division of

Taxation publishes monthly reports on the five

percent state hotel tax, and a separate monthly report

on the one percent local hotel tax, with the most

recent available report created in June 2018 (RI

Division of Taxation, 2018). According to the RI

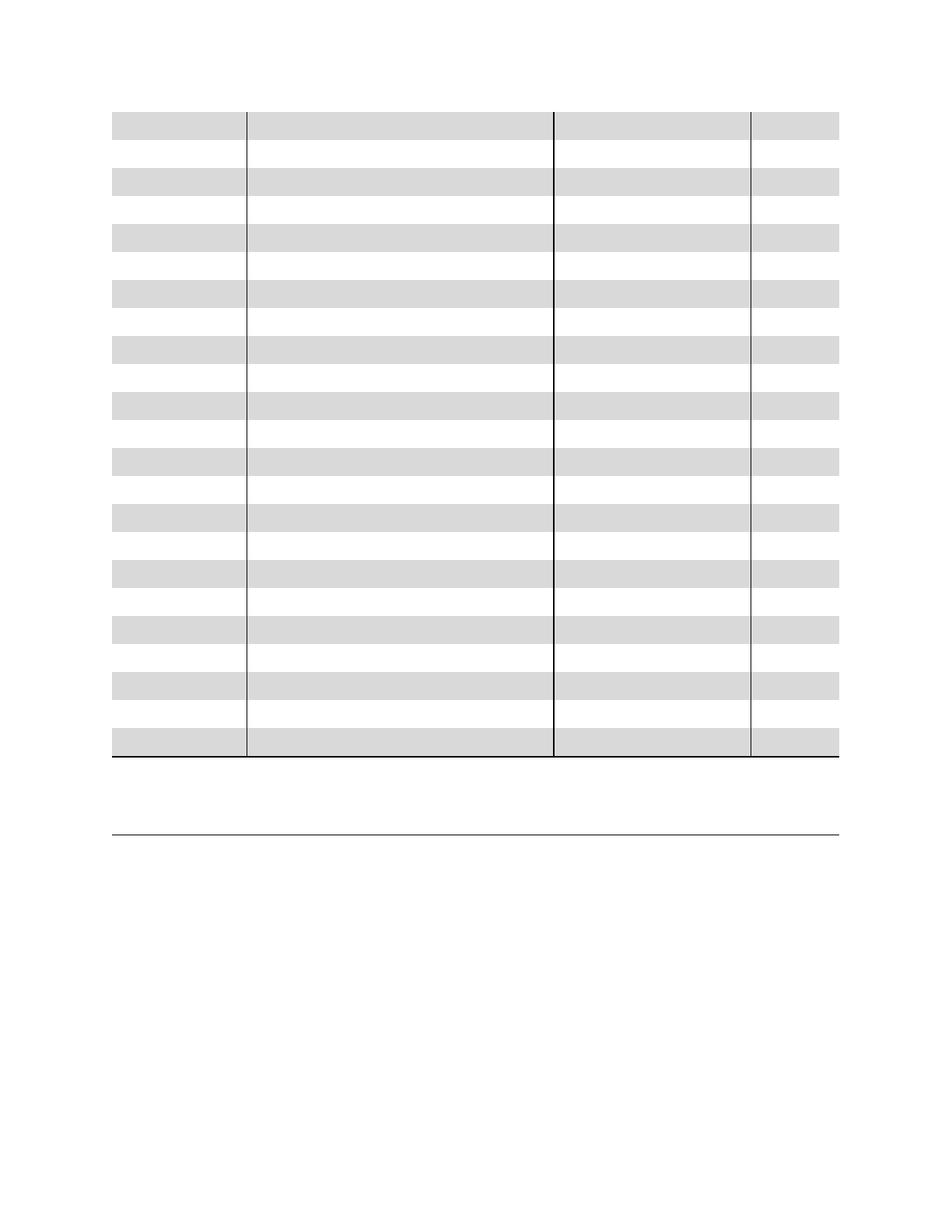

Division of Taxation, in FY18 municipalities

received a total of $10,138,681 as revenue from state

and local hotel taxes. It is very important to note that

both the state hotel tax and the local hotel tax is

mostly comprised of taxes on hotel rooms, not STRs.

Newport, which collected the largest amount of taxes,

18

collected $2,561,498 from hotels but only generated $195,528 from hosting platforms. The five

municipalities generating the most revenue from both taxes combined, only earned between two and eight

percent of that total from STRs. An overwhelming 90 percent of all combined municipal revenue from

hotel and local taxes comes from hotels. There are exceptions with New Shoreham, Narragansett,

Charlestown, Jamestown, and Little Compton each earning between 51 and 74 percent of hotel and local

tax revenue from STRs. The cause for this discrepancy might be due to a number of factors, including a

lack of major hotels or different types of tourism, but these communities in particular may benefit from an

increased focus on STR taxes.

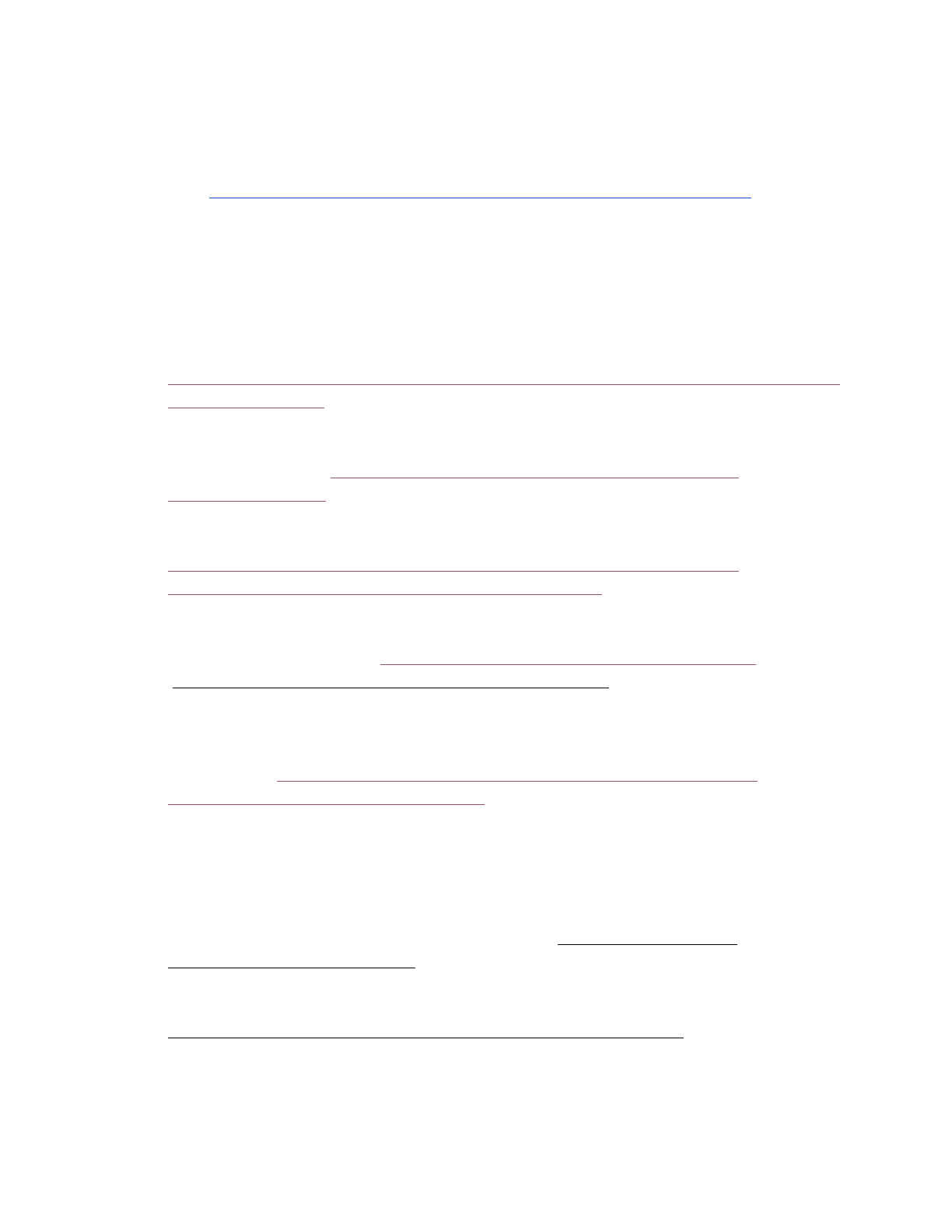

Another aspect of municipal income from STRs is the difference between room rentals and whole

home rentals. Municipalities receive a total of 2.25 percent from room rentals and only receive one

percent from whole home rentals. This is because the room rentals are subject to the state hotel tax, and

the whole home rentals are only subject to the local hotel tax. The majority of rentals in Rhode Island are

whole home rentals, around 70 percent. As mentioned before, STRs account for only ten percent of total

tax income for municipalities, and of that ten percent, 72 percent of municipal income is from whole

home rentals, while 28 percent is from room rentals. This will provide a basis for alternatives one and

two, which are described below.

The real issues municipalities face in terms of taxing STRs is in supporting the related

enforcement costs, should municipalities choose to regulate STRs. The overwhelming majority of Rhode

Island municipalities, 28 of the 39, received less than $10,000 in FY 2018, with 12 municipalities earning

less than $1,000. For most communities, the revenue generated from all STR taxes increased from FY17

to FY18, as would be expected from a growing industry. Most municipalities saw growth in the double

digit percentage range, while some increased or decreased by hundreds or thousands of percentage points,

which is likely due to a community having a small number of STRs and having new STRs emerge or the

19

few existent STRs go away. Overall, tax revenues from STRs to municipalities have been increasing over

time. For those communities with hotels, tax collections have been relatively flat by comparison, except

when new hotels are built. Whatever the case, municipalities should carefully consider the potential tax

earnings of developing an enforcement plan because at first glance funding it through permitting systems

and fines may prove to be an insufficient funding source. We will now list potential alternatives to

address the varying municipal needs.

Table 2

Municipal Revenue from Hotel and Local Taxes*

Municipality

Hotels

% of Total

STRs

% of Total

Totals

Newport

2,365,970

92%

195,528

8%

2,561,498

Providence

2,135,679

96%

87,827

4%

2,223,506

Warwick

1,218,075

98%

30,651

2%

1,248,726

Middletown

1,030,140

96%

43,829

4%

1,073,969

Westerly

639,061

93%

47,403

7%

686,464

New Shoreham

310,333

48%

342,673

52%

653,006

Narragansett

132,421

49%

139,302

51%

271,723

South Kingstown

166,960

85%

29,146

15%

196,106

Smithfield

163,623

99%

2,450

1%

166,073

West Warwick

151,434

99%

2,106

1%

153,540

West Greenwich

120,731

98%

2,741

2%

123,472

North Kingstown

107,510

96%

4,651

4%

112,161

Lincoln

110,801

99%

1,104

1%

111,905

Coventry

105,244

98%

1,994

2%

107,238

Pawtucket

86,540

96%

3,465

4%

90,005

Charlestown

18,327

26%

50,954

74%

69,281

Bristol

56,266

91%

5,286

9%

61,552

Woonsocket

50,935

98%

1,127

2%

52,062

East Providence

44,091

94%

2,950

6%

47,041

Jamestown

7,290

26%

20,445

74%

27,735

Cranston

21,027

85%

3,829

15%

24,856

Little Compton

5,805

29%

14,245

71%

20,050

Portsmouth

10,292

60%

6,810

40%

17,102

Johnston

7,159

97%

251

3%

7,410

Scituate

6,746

96%

249

4%

6,995

Richmond

3,845

59%

2,683

41%

6,528

20

Tiverton

-

-

3,645

100%

3,645

North Smithfield

3,148

98%

76

2%

3,224

Glocester

2,944

96%

110

4%

3,054

Barrington

-

0%

2,973

100%

2,973

Hopkinton

742

44%

931

56%

1,673

East Greenwich

762

69%

347

31%

1,109

Cumberland

-

-

834

100%

834

Warren

-

-

826

100%

826

Foster

560

88%

74

12%

634

North Providence

-

0%

519

100%

519

Central Falls

-

0%

123

100%

123

Burrillville

-

-

63

100%

63

Exeter

-

-

-

-

-

Totals

9,084,461

1,054,220

10,138,681

*RI Division of Taxation FY 18 TYD data from June 2018

Table 3

FY 2018 Municipal Income from STR taxes*

Municipality

1.25% Room

Rentals

1% Room

Rentals

% of

Total

1% Whole Home

Rentals

% of

Total

Totals

New Shoreham

2,527

2,023

1%

338,123

99%

342,673

Newport

53,128

42,503

49%

99,897

51%

195,528

Narragansett

4,691

3,754

6%

130,857

94%

139,302

Providence

47,535

38,028

97%

2,264

3%

87,827

Charlestown

479

383

2%

50,092

98%

50,954

Westerly

1,522

1,217

6%

44,664

94%

47,403

Middletown

10,726

8,581

44%

24,522

56%

43,829

Warwick

16,826

13,461

99%

364

1%

30,651

South Kingstown

3,148

2,518

19%

23,480

81%

29,146

Jamestown

3,919

3,136

35%

13,390

65%

20,445

Little Compton

563

450

7%

13,232

93%

14,245

Portsmouth

1,167

934

31%

4,709

69%

6,810

Bristol

1,137

877

38%

3,272

62%

5,286

North Kingstown

868

694

34%

3,089

66%

4,651

Cranston

1,747

1,399

82%

683

18%

3,829

Tiverton

528

422

26%

2,695

74%

3,645

21

Pawtucket

1,819

1,455

94%

191

6%

3,465

Barrington

312

250

19%

2,411

81%

2,973

East Providence

1,594

1,275

97%

81

3%

2,950

West Greenwich

560

448

37%

1,733

63%

2,741

Richmond

1,369

1,094

92%

220

8%

2,683

Smithfield

823

658

60%

969

40%

2,450

West Warwick

1,170

936

-

-

-

-

Coventry

993

795

90%

206

10%

1,994

Woonsocket

627

500

-

-

-

-

Lincoln

313

208

47%

583

53%

1,104

Hopkinton

137

110

27%

684

73%

931

Cumberland

89

71

19%

674

81%

834

Warren

122

98

27%

606

73%

826

North Providence

288

231

-

-

-

-

East Greenwich

173

138

90%

36

10%

347

Johnston

95

76

68%

80

32%

251

Scituate

137

112

-

-

-

-

Central Falls

70

53

-

-

-

-

Glocester

61

49

-

-

-

-

North Smithfield

42

34

-

-

-

-

Foster

41

33

-

-

-

-

Burrillville

35

28

-

-

-

-

Exeter

-

-

-

-

-

-

Totals

161,381

129,032

763,807

1,049,773

Combined Room

Total

290,413

*FY 18 TYD data from June 18

Alternative 1: Petition the state to make tax rates uniform whole home and room rentals.

Municipalities can lobby the state legislature to add a new 1.25 percent local hotel tax on whole

home STRs. This would make the tax rate between room rentals and whole home rentals more equitable,

or at least allow municipalities to generate more revenue since 70 percent of listings are whole home

rentals, and 72 percent of tax revenues are generated by whole home rentals. Of the $1,049,773 generated

by STRs in FY18, $763,807 came from whole home rentals. Creating an additional 1.25 percent local

hotel tax would have generated an additional $954,758.75 in municipal revenue in FY18 and over $1

million in future years (assuming that the tax increase does not deter STR renting behavior). From a

political feasibility standpoint, this option can be framed as leveling the playing field for all operators, and

the legislature may be more inclined to approve this small increase. As with all tax increases there may be

22

pushback from operators or platforms, but this increase keeps Rhode Island on the low end of STR taxes

when compared with regional states. Connecticut, for example, imposes a 15 percent room occupancy tax

and allows an additional one percent local tax, totaling 16 percent for STRs (State of Connecticut

Department of Revenue Services, 2017). Changing the current STR taxing structures to bring whole home

rentals to the same 2.25 percent received from room rentals may help municipalities cover the cost of

their enforcement efforts, especially considering that the overwhelming majority of STRs are whole home

rentals.

Alternative 2: Petition the state to extend the state hotel tax to all STRs.

Similar to Alternative 1, this option requires municipalities to petition the state to change state

law to include all STRs under the umbrella of the state hotel tax. This option not only provides

municipalities with a larger tax base and all the benefits listed in alternative 1, but will also benefit the

other state recipients of the five percent state hotel tax. This is similar to Alternative 1, but may be more

or less politically viable depending on the disposition of the legislature. The additional benefit Alternative

2 provides is that taxes on all STRs will be exactly the same; all STRs will have a seven percent sales tax,

a five percent state hotel tax, and a one percent local hotel tax for a total tax rate of thirteen percent. This

alternative will simplify tax considerations across the board for operators, consumers, and platforms. This

alternative also has the benefit of not necessarily being a new tax, but an extension of an existing tax to

create uniformity and bring Rhode Island in line with other regional states. In Connecticut and New

Hampshire STR taxes apply to all STRs, regardless of whether they are a room or whole home rental. The

possible costs to this alternative are that it is a larger tax increase and it affects a large pool of operators.

Care would have to be taken to promote the tax increase as leveling the playing field and simplifying the

tax structure. Additionally, the legislature would need to change the current definition of hotels to apply

the state hotel tax on whole home rentals, which are currently not considered hotels.

Alternative 3: Municipality control of taxes.

Giving municipalities control over choosing STR tax rates would allow for independent

assessment and control of STR activity within a municipality. Currently, all 39 municipalities receive

revenue from the state hotel tax at fixed percentages depending on STR rental type. As already described

above, all 39 municipalities in Rhode Island receive 2.25 percent for room rentals and one percent for

whole home rentals from the five percent state hotel tax. Adopting a model as such would require

municipalities to ask the state to allow municipalities to create and collect their own local hotel tax instead

of receiving monthly payments from the Rhode Island Department of Revenue. The benefit of allowing

municipalities to determine their own STR tax rates allows municipalities to control STR activity by

tailoring STR taxes to either attract STR customers where STR type activity is low, or to dissuade STRs

by administering higher taxes. This model allows municipalities to limit nuisance issues by increasing

taxes where STR prevalence is high. At the current taxing structure model, revenue received from

municipalities significantly varies in Rhode Island due to varying STR activity or hotel prevalence as a

potential alternative to STR utilization. For example, in Woonsocket, 98 percent of municipal revenue

received from hotel and local taxes is generated from hotels whereas two percent of the revenue is

generated from STRs in FY18. For a city like Woonsocket, STR prevalence could be increased by

allowing the municipality to have control of STR taxes. Adopting a model similar to California, which

does not have a state-level lodging tax, would allow Rhode Island to implement a transient occupancy tax

23

(TOT) which is administered as a locally-imposed tax paid by guests who stay at hotels or similar

establishments in a municipality that levies the tax. This model allows each municipality in California to

have its own unique TOT and, depending on the municipality, the tax rate can reach up to 16 percent

(Sheyner, 2018). Florida has a six percent state sales tax, which applies to rental charges or room rates for

rental periods six months or less, often called “transient rental accommodations” or “transient rentals.”

Individual Florida counties may impose a local option tax. Local option transient rental taxes include the

tourist development tax, convention development tax, tourist impact tax, and municipal resort tax. The

local tax imposed is in addition to the six percent state sales tax and any applicable discretionary sales

surtax (Florida Department of Revenue, 2018). The local tax ranges from zero percent to six percent.

Counties either collect this local tax independently or it is collected by the state department. Municipal

control of STR taxes provide the opportunity for municipalities to tax based on the impact STRs are

having in their community.

Alternative 4: Do nothing.

Municipalities may decide not to attempt to change the tax rates or expand the base by including

whole homes in the hotel tax. There may be several reasons for doing nothing, including: political

headwinds that make legislative changes unlikely, limited new revenue generation from alterations in the

tax structure and rate, and lack of municipal staff time and energy to exert on advocacy efforts with the

General Assembly.In each of these cases municipalities may want to rely on a standard permitting system.

This would maintain the status quo, which does not necessarily improve accountability, but would save

time and energy while allowing the continued receipt of taxes at the current rates.

24

Recommendations and Conclusion

We have analyzed the various policy options that are available to cities and towns in Rhode

Island for regulating STRs. We found that municipalities can combine various alternatives discussed in

this analysis to address unique STR issues that cities and towns may face. Municipalities can respond to

nuisance and long-term housing concerns by requiring rental properties to be the operator’s primary

residence. This alternative limits the amount of the property that can be used as an STR since the property

must be used as a primary residence for a specific number of days in the year. Since properties will be

used as an STR for a limited time, there are fewer opportunities to generate nuisances as a result of

renting out the property. This alternative also addresses long-term housing concerns as it prohibits

commercial operators (those who rent out three or more properties) from using STR properties like hotels.

Units can then be rented out as long-term rentals, adding to the available housing stock. The downside to

this approach is the fierce criticism, and potential legal action, that comes from commercial operators and

owners who have purchased property for the sole purpose of generating income. Restricting the amount of

rented days a property can be used as an STR is another alternative that addresses both nuisance and

housing concerns. Limiting the number of days a property can be used as an STR can limit the number of

days nuisance behavior occurs. A municipality can choose to tailor this quantitative limitation on the basis

of the severity of its housing shortage and nuisance issues.

Given the diversity of Rhode Island’s 39 municipalities, the alternatives we described in this

analysis do not lend themselves well to a one-size-fits-all recommendation. Depending on community

composition and characteristics, municipalities can combine various alternatives discussed in this report

to address unique STR issues experienced. For example, we would not recommend hiring a municipal

enforcement agent for a city like Johnston with only three percent of the state hotel tax share generated

from STRs totaling $7,410 annually. For municipalities like Newport, however, a mix of alternatives such

as high fines and having municipal oversight and control would allow the municipality to address

neighborhood nuisance concerns. Our analysis demonstrates that the front-end costs of contracting out to

a private entity can be offset by the revenue received from taxes, permitting fees, and noncompliance

fines. The revenue from taxes, fees, and fines could be used to support STR officers hired by

municipalities to continuously monitor and enforce STR requirements. For municipalities like Newport,

this approach may be feasible due to the $2,561,498 in annual revenue it receives from the state hotel tax

that can be used to support start-up costs for STR program monitoring and personnel hiring.

Municipalities receiving less than $10,000 annually from STRs may consider a more traditional approach

where free permitting, tracking, and fining offenders is emphasized. This will at least allow municipalities

to stay abreast of their changing STR environment so that changes can be made as needed.

Overall, municipalities must contend with a variety of challenges in managing their approach to

the STR marketplace. Most notably, the procedural burdens on tax rate adjustments and the risk of

litigation from STR platforms can limit the options that are available. The viability of the various policy

alternatives discussed in this report will depend on the needs and demographic characteristics of the

municipality.

25

26

References

A.P. (2018, November 13). Airbnb Sues Boston Over Short-Term Rental Rules. CBS Local.

Retrieved

From https://boston.cbslocal.com/2018/11/13/airbnb-sues-boston-lawsuit-short-term- rental-rules/

Abcarian, R. (2015, May 22). In San Francisco, a battle over the 'hotelization' of neighborhoods.

Retrieved from

http://www.latimes.com/local/abcarian/la-me-0522-abcarian-sharing-economy-20150522-column

.html

Bridges, B. (2017, September 2). Airbnb Seen as Creating Uneven Playing Field (N., Ed.). from

http://www.newportthisweek.com/news/2017-02-09/Front_Page/Airbnb_Seen_as_Creating_Unev

en_Playing_Field.html

Connecticut Department of Revenue. (2017). Room Occupancy Tax on Short-Term Home Rentals.

CT.gov.

Retrieved fromhttps://portal.ct.gov//media/DRS/Publications/pubsps/2017/

PS20173pdf.pdf?la=en

Denvergov.org. (2018). Denver Short-term Rental License FAQ. Retrieved from

https://www.denvergov.org/content/denvergov/en/denver-business-licensing-center

/business-licenses/short-term-rentals/short-term-rental-faq.html

Department of Revenue, Division of Taxation. (2015). Sales and hotel taxes on short-term residential

rentals: FAQs. Retrieved from http://www.tax.ri.gov/notice/Short-term%20residential

%20rentals%20--%20FAQs%20--%2008-28-18%20revised.pdf

DiNatale, S., Lewis, R., and Parker, R. (2017). Assessing and Responding to Short-term Rentals in

Oregon. University of Oregon, Department of Planning, Public Policy and Management.

Retrieved from https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/22520/

DiNatale_final_project_2017.pdf?sequence=3

Edelman, B. G., & Geradin, D. (2015). Efficiencies and regulatory shortcuts: How should we regulate

companies like Airbnb and Uber. Stan. Tech. L. Rev., 19, 293.

Florida Department of Revenue. (2018). Sales and Use Tax on Rental of Living or Sleeping

Accommodations. Floridarevenue.com.

Retrieved from: http://floridarevenue.com/

Forms_library/current/gt800034.pdf

Flynn, S. (2017, August 02). Landlord fined $15K for illegal rentals. Retrieved from

http://www.newportri.com/0212b01d-4141-5b80-829c-a465d5aa78bb.html

Flynn, S. (2018, November 09). Newport to weigh actions on short-term rentals. Newportri.com

27

Retrieved from http://www.newportri.com/news/20181108/newport-to-weigh-actions-on-short-

term-rentals

Gurran, N., & Phibbs, P. (2017). When tourists move in: how should urban planners respond to Airbnb?

Journal of the American planning association, 83(1), 80-92.

Guttentag, D. (2016). Why tourists choose Airbnb: A motivation-based segmentation study

underpinned by innovation concepts (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from

https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/handle/10012/10684

Horn, K., & Merante, M. (2017). Is home sharing driving up rents? Evidence from Airbnb in Boston.

Journal of Housing Economics, 38, 14-24.

Host Compliance. (2018). Home-sharing and Short-term Rentals Regulations FAQ. Retrieved from

https://hostcompliance.com/short-term-vacation-rental-faqs/

Inside Airbnb. (2018). Rhode Island. Retrieved from http://insideairbnb.com/rhode-island/

Jefferson-Jones, J. (2015). Can short-term rental arrangements increase home values? A case for

Airbnb and other home sharing arrangements. Cornell Real Estate Review

, 13(1), 12-19.

Retrieved from http://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/crer/vol13/iss1/5

Kaplan, R. A., & Nadler, M. L. (2015). Airbnb: A case study in occupancy regulation and taxation.

University of Chicago Law Review Dialogue, 82

, 103.

Klacik, D. (2003) Affordable housing key to economic development. Central Indiana.

Indianapolis, IN: Center for Urban Policy and the Environment.

Lauer, N. C. (2018). Most vacation rental owners not paying taxes. Retrieved from

http://www.westhawaiitoday.com/2018/02/27/hawaii-news/most-vacation-rental-owners-n

ot-paying-taxes/?sessionId=1538934533982&referrer=https://www.google.com/&lastRef

errer=www.avalara.com

Lee, D. (2016). How Airbnb short-term rentals exacerbate Los Angeles's affordable housing crisis:

Analysis and policy recommendations. Harv. L. & Pol'y Rev., 10, 229. (JC)

http://harvardlpr.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/10.1_10_Lee.pdf

Lutz, C., & Newlands, G. (2018). Consumer segmentation within the sharing economy: The case of

Airbnb. Journal of Business Research, 88, 187-196.

Malm, L. (2017). 2017 Legislative Update. National Conference of State Legislatures.

Retrieved from http://www.ncsl.org/documents/taskforces/Short_term_rental_tax_

update.pdf

28

Miami-Dade County. (2018). Short-Term Vacation Rentals. Miami-Dade.gov.

Retrieved from

https://www.miamidade.gov/building/standards/residential-short-term-vacation-rentals.

Asp

Nieuwland, S. & Van Melik, R. (2018). Regulating Airbnb: how cities deal with perceived negative

externalities of short-term rentals. Current Issues in Tourism, p. 1-15. (AA)

https://www-tandfonline-com.uri.idm.oclc.org/doi/pdf/10.1080/13683500.2018.1504899?needAc

cess=true

Nguyen, Taheri, & Valenta. (2016). Designing Enforceable Regulations for the Online Short-Term Rental

Market in Los Angeles. Retrieved from

https://www.lewis.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/09/2015-2016_Nguyen_Taheri_Vale

nta_AirbnbEnforcement.pdf

Njus, E. (2018). Portland, vacation rental site HomeAway settle dispute over lodging taxes. Retrieved

from https://www.oregonlive.com/front porch/index.ssf/2018/02/portland_vacation_

rental_site.html

Oskam, J., & Boswijk, A. (2016). Airbnb: the future of networked hospitality businesses. Journal of