Report

by the Comptroller

and Auditor General

Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government

Help to Buy: Equity Loan

scheme – progress review

HC 2216 SESSION 2017–2019 13 JUNE 2019

A picture of the National Audit Office logo

Our vision is to help the nation spend wisely.

Our public audit perspective helps Parliament hold

government to account and improve publicservices.

The National Audit Office (NAO) helps Parliament hold government to account

for theway it spends public money. It is independent of government and the civil

service. The Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG), Gareth Davies, is an Officer

of the House of Commons and leads the NAO. The C&AG certifies the accounts of

all government departments and many other public sector bodies. He has statutory

authority to examine and report to Parliament on whether government isdelivering

value for money on behalf of the public, concluding on whether resources have

been used efficiently, effectively and with economy. The NAO identifies ways

that government can make better use of public money to improve people’s lives.

Itmeasures this impact annually. In 2018 the NAO’s work led to a positive financial

impact through reduced costs, improved service delivery, or other benefits to

citizens, of £539 million.

Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General

Ordered by the House of Commons

to be printed on 11 June 2019

This report has been prepared under Section 6 of the

National Audit Act 1983 for presentation to the House of

Commons in accordance with Section 9 of the Act

Gareth Davies

Comptroller and Auditor General

National Audit Office

10 June 2019

HC 2216 | £10.00

Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government

Help to Buy: Equity Loan

scheme – progress review

This report assesses whether the Help to Buy:

EquityLoan scheme has been value for money to date,

and whether it is likely to be so in the future.

© National Audit Office 2019

The material featured in this document is subject to

National Audit Office (NAO) copyright. The material

may be copied or reproduced for non-commercial

purposes only, namely reproduction for research,

private study or for limited internal circulation within

an organisation for the purpose of review.

Copying for non-commercial purposes is subject

to the material being accompanied by a sufficient

acknowledgement, reproduced accurately, and not

being used in a misleading context. To reproduce

NAO copyright material for any other use, you must

contact [email protected]. Please tell us who you

are, the organisation you represent (if any) and how

and why you wish to use our material. Please include

your full contact details: name, address, telephone

number and email.

Please note that the material featured in this

document may not be reproduced for commercial

gain without the NAO’s express and direct

permission and that the NAO reserves its right to

pursue copyright infringement proceedings against

individuals or companies who reproduce material for

commercial gain without our permission.

Links to external websites were valid at the time of

publication of this report. The National Audit Office

isnot responsible for the future validity of the links.

006336 06/19 NAO

The National Audit Office study team

consisted of:

Andy Whittingham, Alison Taylor,

OliverSheppard and John Anderson,

under the direction of Aileen Murphie.

This report can be found on the

National Audit Office website at

www.nao.org.uk

For further information about the

National Audit Office please contact:

National Audit Office

Press Office

157–197 Buckingham Palace Road

Victoria

London

SW1W 9SP

Tel: 020 7798 7400

Enquiries: www.nao.org.uk/contact-us

Website: www.nao.org.uk

Twitter: @NAOorguk

Contents

Key facts 4

Summary 5

Part One

About the Help to Buy:

EquityLoanscheme 14

Par t Two

The impact of the scheme 22

Part Three

Managing the Department’s

investment 37

Part Four

The future of the scheme 42

Appendix One

Our audit approach 47

Appendix Two

Our evidence base 49

Appendix Three

Regression analysis 51

If you are reading this document with a screen reader you may wish to use the bookmarks option to navigate through the parts.

4 Key facts Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

Key facts

211,000

equity loans made to

buyers in England by

December 2018

£11.7bn

loaned in total in England

by December 2018

14.5%

is the Ministry of

Housing, Communities

& Local Government’s

(theDepartment’s) estimate

of the increase in new-build

housing supply in England

as a result of the scheme

352,000

is the Department’s forecast of the number of home purchases

to be supported by Help to Buy equity loans in England by

March2021

37%

is the proportion of buyers in England who said they could not have

bought without the support of the scheme (measured between

June 2015 and March 2017)

31%

is the proportion of buyers in England who said they could have

bought a property they wanted without the support of the scheme

(measured between June 2015 and March 2017)

38%

is the proportion of new-build properties which have been sold with

the scheme in England between April 2013 and September 2018

4%

is the proportion of all property sales which have been sold with the

scheme in England between April 2013 and September 2018

81%

is the proportion of Help to Buy loans provided to fi rst-time buyers

in England, at December 2018

5%

is the proportion of buyers in arrears who bought in the fi rst

elevenmonths of the scheme in England, at February 2019

2031-32

is the year by which the Department estimates it will have

recoupedits investment in full

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Summary 5

Summary

Our report

1 The Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme (the scheme) aims to support the delivery

of the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government’s (the Department’s)

strategic objective to “deliver the homes the country needs”, through increasing

homeownership and increasing housing supply. It is the Department’s largest

housing initiative by value.

2 The government introduced the Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme to address

a fallin property sales following the financial crash of 2008 and the consequent

tighteningof regulations by the regulatory authorities over the availability of high

loan-to-value and high loan-to-income mortgages. The scheme has two principal

aims:to help prospective homeowners obtain mortgages and buy new-build

properties;and, through the increased demand for new-build properties, to

increasetherate ofhousebuildinginEngland.

3 Homes England, an executive non-departmental public body sponsored by

the Department, launched the scheme in April 2013 on behalf of the Department.

Thecurrent scheme will run to March 2021. Through the scheme, home buyers receive

an equity loan of up to 20% (40% in London since February 2016) of the market value of

an eligible new-build property, interest free for five years. The value of the loan changes

in proportion to changes in the property’s value. The loan must be paid back in full on

sale of the property, within 25 years, or in line with the buyer’s main mortgage if this

is extended beyond 25 years. Thescheme enables buyers to purchase a new-build

property with a mortgage of 75% of the value of the property. The scheme, which

is not means-tested, is open to both first-time buyers and those who have owned a

propertypreviously. Buyers can purchase properties valued up to £600,000.

4 The scheme is demand-led, meaning all eligible applications would be accepted,

with funding provided to meet demand. The scheme does not therefore have

targets either for the number of households supported to buy or for the additional

number of new homes built. The Department expects the scheme to support around

352,000property purchases by March 2021, via loans totalling around £22 billion in

cash terms. A new scheme, to follow on immediately from the current scheme for

twoyears to March2023, will be restricted to first-time buyers and will introduce lower

regional caps on the maximum property value, while remaining at £600,000 in London.

HomesEngland expect to have loaned around £29 billion in total in cash terms by

March2023, supporting 462,000property purchases.

6 Summary Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

Scope of our report

5 This report follows up on our March 2014 report The Help to Buy equity loan

scheme. Itcontinues a series of reports we have published on housing in England,

which have included Housing in England: overview (January 2017), Homelessness

(September 2017) and Planning for new homes (February 2019).

6 In our 2014 report, we examined the performance of the Department for

Communities & Local Government (now the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local

Government) and the Homes and Communities Agency (now Homes England) in

designing and implementing the scheme. We found that they had started the scheme

well, early demand for the scheme was strong, and that the scheme was improving

buyers’ access to mortgages.

7 Since our first report, the scheme has increased considerably in size and value.

This report assesses how the scheme has performed against its objectives, how

effectively the Department and Homes England have managed the Help to Buy: Equity

Loan scheme to date, and how they are planning the future of the scheme and its end.

This report does not examine whether quality standards for new-build properties are

either adequate or have been met.

Key findings

The scheme’s performance

8 The Department’s independent evaluations of the Help to Buy: Equity

Loan scheme show it has increased home ownership and housing supply.

HomesEngland had made around 211,000 loans by December 2018, amounting

to £11.7billion. TheDepartment commissioned two independent evaluations of

the scheme, which included sample surveys of households that had bought using

the scheme, and interviews with developers and lenders. Around two-fifths of

householdssaid they would not have been able to buy any property without the support

of the scheme. The Department did not set quantified objectives for the scheme,

butexpected that between 25% and 50% of sales would result in new homesbeing

built. Thesecondevaluation, covering loans made between June 2015 and March2017,

concluded that the rate of building had increased by 14.5% because of thescheme

(paragraphs1.3and2.2 to 2.6).

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Summary 7

9 The scheme has helped increase the number of new-build properties being

sold. Between the start of the scheme and September 2018, 38% of all new-build

property sales have been supported by loans through the scheme, equating to

around 4% of all housing purchases. Since the scheme was introduced in 2013, the

number of new-build property sales has increased from 61,357 per year in 2012-13 to

104,245peryear in 2017-18. Sales of new-build properties have also increased from

around 9% of all property sales in 2014 to over 12% in 2017. From 2013, the scheme

contributed to a general increase in transactions throughout the housing market and

planning system, although the Department acknowledges that the rate of transactions

was picking up before the start of the scheme and the housing market is sensitive to

arange of economic factors (paragraph 2.7).

10 The scheme has helped fewer people to buy new-build properties in areas

where less housing is available for sale below £600,000. Excluding London,

between the start of the scheme and December 2015, the proportion of new-build

properties bought with the support of the scheme ranged from 29% in the south east

to 42% in the north east. Over the same period the proportion was only 12% in London,

where the ratio of median house prices to median earnings is greatest (lessaffordable

areas as defined by the Office for National Statistics) and where there are fewer

new-build properties below the cap. In February 2016, the government decided

that it needed to improve the take up of the scheme in London, while accepting the

variation across other regions of England. It increased the maximum loan in London

to 40% of the property value. The change improved the scheme’s take-up in London,

to 26% of new-build sales between January 2016 and September 2018, although this

is still lower than the rest of England (46% of new-build sales over the same period)

(paragraphs2.8to2.9).

8 Summary Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

Buyers

11 The Department’s second evaluation found that around three-fifths of buyers

could have bought a property without the support of Help to Buy. The Department

intentionally set broad eligibility criteria for the scheme to enable as many households as

possible to benefit, not just first-time buyers. There are no limits on household income

and no restrictions on the number of scheme beneficiaries. As at December 2018 around

81% of all buyers supported by the scheme have been first-time buyers. TheDepartment’s

second evaluation, covering loans made between June 2015 and March2017, found that:

•

37% of buyers stated that they could not have bought without the support of the

scheme. We estimate this to be around 78,000 additional sales of new-build properties

since the scheme started.

•

63% of first-time buyers were aged 34 and under.

However, the evaluation also found that:

•

19% of buyers have previously owned a property and are using the scheme to buy,

on average, more expensive properties than first-time buyers using the scheme. We

estimate that thisequates to nearly 40,000 households (paragraphs 2.5 and 2.10 to 2.12).

•

31% of buyers could have purchased a property they wanted without the scheme.

Extrapolating this proportion over the whole of the scheme suggests that around

65,000 households could have purchased a property they wanted without the scheme.

12 Some 4% of the 211,000 buyers who had used the scheme by December 2018

had household incomes over £100,000. The proportion has increased each year, from

3%in 2013 to 5% in 2018. Over the whole scheme, 10% of buyers had household incomes

over £80,000 (or over £90,000 in London), the thresholds above which they would not be

eligible for the Department’s shared ownership housing scheme (also designed to help

with home ownership). TheDepartment regards these transactions as an acceptable

consequence of designing the scheme to be widely available. The Department also intended

to keep the scheme simple to administer andeasy for applicants to access (paragraph 2.14).

Help to Buy properties

13 The scheme has enabled buyers to purchase properties with more bedrooms,

or to buy a property more quickly, than they would otherwise have been able to.

Buyers have been able to borrow more through taking out both a mortgage and an

equity loan than they could have borrowed through a mortgage alone. Around four-fifths

of buyers reported, through the evaluations, that the scheme had enabled them to buy a

property sooner. Buyers took out mortgages and equity loans that together were typically

around four and a half times their annual income (increasing to over six times in London).

In contrast, first-time buyers generally took out mortgages that were three and a half times

their annual income over the same period. The increased spending power of buyers using

the scheme has contributed towards developers building properties with more bedrooms.

Though not a stated objective, the Department regards the scheme’s support to buyers

to move up the property ladder more quickly as a positive outcome, as it brings more

properties onto the market for other buyers (paragraphs 2.5, 2.12 and 2.13).

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Summary 9

14 Buyers who want to sell their property soon after they purchase it might find

they are in negative equity. New-build properties typically cost around 15%–20%more

than an equivalent ‘second-hand’ property, termed the ‘new-build premium’, which

reflects that these properties have yet to be lived in. The new-build premium fell away

following the financial crash of 2008 but has since recovered to pre-crash levels, as

wider economic and housing market conditions have changed, and sales of new-build

properties have increased (paragraphs 2.15 and 2.16).

15 Our analysis indicates that buyers who used the scheme have paid less

than 1% more than they might have paid for a similar new-build property bought

without an equity loan. By comparing prices paid for similar new-build properties in

the same area with and without the scheme, we estimate that buyers supported by the

scheme have paid less than 1% more. Our estimate is significantly less than others in

the public domain, which range between 5% and 20%. We found that these estimates

do not compare similar properties and so do not accurately assess any additional

premium paid by those using the scheme on top of the new-build premium. We have

not, however, quantified other financial incentives that buyers of properties without the

scheme might receive. Incentives on properties sold with the support of the scheme

are restricted to 5% of the total purchase price, but there is no restriction on incentives

onnew-build sales generally (paragraphs 2.17 and 2.18).

Developers

16 The scheme has supported five of the six largest developers in England

to increase the overall number of properties they sell year on year, thereby

contributing to increases in their annual profits. Five of the six developers in England

that build most properties account for over half of all loans through the scheme. Theysell

a greater proportion of properties with the support of the scheme than other developers.

Between 36% and 48% of properties sold by these five were sold with the support of

the scheme in 2018. The profits of all five developers have increased since the start of

the scheme. Over the same period, total combined housing completions for these five

developers have increased by over a half. It is not possible to determine what proportion

of a developer’s profits directly relates to sales through the scheme because this

information is not publicly available (paragraphs 2.19 to 2.21).

17 Some small and medium-sized developers have required more help than

anticipated from Help to Buy agents to engage with the scheme. The Department

designed the scheme so that it is easier for smaller firms to access. More small and

medium-sized developers have joined the scheme than joined previous schemes with

similar aims. By December 2018, 2,000 developers were registered with the scheme,

the majority of whom are small and medium-sized developers. However, some small

and medium-sized developers have struggled with the administration required to join

thescheme and sell properties with its support (paragraphs 2.19 and 2.20).

10 Summary Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

The government’s investment in the scheme

18 By 2023, the government will have invested up to £29 billion in the scheme,

tying up cash which cannot be used elsewhere. Homes England had loaned around

£11.7 billion by December 2018 and estimates it will have loaned around £22 billion in

cash terms by the close of the current scheme in 2021, rising to around £29 billion in

cash terms by the close of the new scheme in 2023. Factoring in the estimated rate of

redemptions, the net amount loaned is forecast to peak at around £25 billion in 2023

in cash terms. There is an opportunity cost in tying up this money in the scheme for a

considerable period, rendering it unavailable for other housing schemes or departmental

priorities (paragraphs 3.2 to 3.5).

19 The Department expects to recover its investment in the medium term and

make a positive return overall, although it recognises the investment is exposed to

significant market risk. By December 2018, Homes England had received £1.3billion

in redemptions, around 11% of the amount loaned. Based on current estimates of

the long-term performance of the housing market, Homes England expects total

redemptions to equal the amount loaned by 2031-32, and to have made a positive

returnon investment by the time all loans are repaid by 2048. However, both the

payback period and the return on investment are sensitive to house price changes and

the timing of buyers repaying loans. Recent housing market data indicate that house

price growth is slowing down, and that there has been a recent fall in prices in some

regions, notablyLondon (paragraphs 3.6 to 3.11).

Interest repayments

20 Homes England has recognised the need to improve processes for

recovering interest. The first homeowners in the scheme started paying interest in

May2018, fiveyears after the first loans were issued. At December 2018, around 7%

ofhomeownersusing the scheme were paying interest; most homeowners are still within

the five-year interest-free period. At February 2019 around 5% of homeowners were

in arrears, and the proportion of interest due that had not been received was around

4%. In almost all cases, homeowners have fallen into arrears because processes to

collect interest were not set up when the loan was issued, and they have not responded

to contact from Target (theorganisation administering the loans on behalf of Homes

England). FromSeptember2016, Homes England has required all homeowners to

set up a direct debit on issue of the loan, in anticipation of the interest payments.

In May2019, the Department approved animproved interest-recoupment policy

(paragraphs 3.12, 3.13and 3.17).

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Summary 11

Contract management

21 Target was not prepared for the volume and complexity of queries from

homeowners once they started redeeming their loans and paying interest.

InMay2018, Target faced an expected increase in enquiries as the first homeowners to

have bought with the support of the scheme came to the end of the interest-free period.

Target had planned on the basis of Homes England’s forecast, but the overall number of

telephone queries received was over 75% higher than the forecast for the previous year.

In addition, the queries received were more complex than predicted, requiring more and

longer interactions with customers. Target experienced problems in dealing with this

higher-than-expected level of engagement. Homes England and Target worked together

to address this, for example Target tripled the number of staff dedicated to administering

the scheme to 75. Homes England is undertaking a digital transformation programme

to speed up and streamline the administration of the scheme and to improve the

experience for buyers (paragraphs 3.14 and 3.16).

22 Homes England’s oversight of its mortgage administrator Target and the Help

to Buy agents needs to improve. In February 2019, Homes England’s internal auditor

gave only a limited assurance opinion for Target’s administration of the HelptoBuy

portfolio due to control weaknesses in several areas of Target’s operations, making a

number of recommendations for further improvement. A second internal audit report,

in March 2019, identified problems with the arrangements at the HelptoBuy agents

for securing documentation to support loans, and Homes England’s limited oversight

of information security arrangements at the agents. Homes England has accepted the

recommendations of the internal audit report and has a number of actions in place to

strengthen its monitoring and oversight for these keycontracts (paragraphs3.15and3.16).

The future of the scheme

23 In October 2018, the Autumn Budget included an announcement that, from

April2021, the new scheme would be targeted towards those who need more

helpinto home ownership. The new scheme will be restricted to first-time buyers.

Outside of London, lower regional limits on the maximum purchase price will restrict

thescheme to buyers purchasing cheaper properties, who are likely to be people

on lower incomes. TheDepartment also intends these changes to reduce overall

demand for the scheme in its finaltwo years, preparing the housing sector for its

end(paragraphs4.4 to 4.10).

12 Summary Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

24 The Department accepts there is less need for the scheme now that higher

loan-to-value mortgages are more available, and plans to end the scheme in

2023. The scheme was introduced in 2013 to address the difficulties that buyers were

experiencing with the availability of high loan-to-value mortgages. Lenders are now

offering high loan-to-value mortgages more widely, but eligibility is more restricted than

before the financial crash of 2008. The Department believes the scheme is therefore

still needed. It has announced the end of the scheme, giving developers and lenders

four and a half years to devise other ways for buyers to raise the necessary finance

to purchase new-build properties. Nevertheless, there is concern across the housing

sector that the end of the scheme will still result in a drop in new developments and

sales (paragraphs 4.2 to 4.4, and 4.11).

Conclusion on value for money

25 The Department’s independent evaluations of the Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme

show it has increased home ownership and housing supply. It seems likely to continue

to do so as long as the scheme remains open, provided there is no significant change

in the housing market. The scheme is therefore delivering value so far against its own

objectives. The Department is currently forecasting a positive return on its investment

and redemptions are running ahead of expectations.

26 Given that the government has entered the equity loan market place, it has put

reasonable arrangements in place to benefit from increasing property prices. However, this

is dependent on the performance of the housing market and property values can go down

as well as up. At points when the market turns down (whether over the near, medium or

longer term), the taxpayer could lose out significantly, as the government’s investment

in housing capital would reduce in value. Furthermore, property owners could face the

trap of negative equity, exacerbated by the new-build premium. Thescheme also has an

opportunity cost in tying up a great deal of financial capacity, and its broad participation

criteria have allowed some people who did not needfinancialhelpto buy a property to

benefit from the scheme.

27 The government has indicated that it will wean the property market off the

scheme.It will need to ensure that developers continue to build new properties at the

rates currently achieved, or better, if it is to meet its challenging ambition of creating

300,000 new homes per year of sufficient quality from the mid-2020s. The scheme

may have achieved the short-term benefits it set out to, but its overall value for money

will only be known when we can observe its longer-term effects on the property market

and the net return, or cost, to the taxpayer when the very substantial portfolio of loans

hasbeenrepaid.

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Summary 13

Recommendations

28 The Department’s greatest challenge is to wind down the scheme to minimise

negative effects on the housing market. It should also seek to maximise, as far as it can,

the return on its investment. Our recommendations aim to support the Department to

achieve these goals.

a Housing market conditions have changed since the start of the scheme.

TheDepartment should assess the existing scheme against current market

conditions and determine whether any changes to how it operates and criteria

foreligibility would increase its impact.

b The Department should consider further changes to the new scheme from 2021

to achieve other housing policy goals, for example to enact the government’s

commitment to addressing the practice of developers selling new houses

asleasehold.

c The Department should plan a further evaluation of the scheme, either soon

toinform the new scheme from 2021, or after the end of the current scheme

to inform potential new initiatives to support home ownership and housing

supplyafter 2023.

d The Department should support Homes England to take appropriate enforcement

action to recover money due from homeowners who have fallen into arrears.

e Homes England should continue to improve its oversight of the Help to Buy agents

and its mortgage administrator Target.

f The Department should review the information given by the Help to Buy agents and

developers to potential buyers, to confirm that it fully explains the financial risks of

buying a new-build property through the scheme.

g The Department has not undertaken a detailed assessment of the impact of the

scheme on the wider housing market. It should expand the scope of its next

evaluation to examine such wider effects, including a potential influence on the

new-build premium, and identify lessons learned for any future interventions.

14 Part One Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

Part One

About the Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme

Background

1.1 The Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (the Department)

aims to support the building of a million new homes in England between April 2015 and

December 2020, and thereafter deliver 300,000 new homes per year by the mid-2020s.

1.2 Housebuilding declined sharply after the financial crash in 2008. The number of

new homes built in England fell from a peak of 160,000 in 2007 to 65,000 in 2009,

before slowly rising again. In response to the financial crash, the regulatory authorities

tightened the rules on mortgage lending to curtail mortgages where the loan exceeds

90% of the property value and is greater than three and a half times the borrower’s

income (two and three-quarter times for joint borrowers). For example, the proportion

of 95% mortgages dropped from a peak of around 6% in 2007 to less than 1% in 2009.

However, this meant some prospective homeowners were not able to obtain mortgages

and buy properties as they needed larger deposits. The government introduced the

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme (the scheme) in 2013 to enable more people to obtain

mortgages and buy new-build properties, thereby stimulating developers to build more

properties to meet the increased demand.

The Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme

1.3 The scheme is demand-led and does not have targets either for the number of

households supported to buy or for the additional number of new homes built. It was

introduced in April 2013 with an initial budget of £3.5 billion to March 2016 (Figure 1).

The Department’s objectives for the scheme, as set out in the business case, were to:

•

support creditworthy, but deposit-constrained, households to buy a

new-buildproperty;

•

increase the supply of new housing; and

•

contribute to economic growth through the achievement of the first two objectives.

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Part One 15

Figure 1 shows Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme timeline

Figure 1

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme timeline

The scheme started in April 2013 and by December 2018 Homes England had loaned a total of £11.7 billion, supporting nearly

211,000 participants into homeownership

£11.7 billion

Amount loaned as

at December 2018

1 Apr 2013

Scheme opens

to public

Feb 2016

London equity share

increased from 20% to 40%

Nov 2015

Scheme further

extended to 2021

Oct 2018

Revised scheme

announced 2021–2023

Current

scheme ends

March2021

Revised

scheme ends

March2023

2048

All loans repaid

Sep 2016

£1 monthly management

fee brought in

£10 billion

additional

funding

announced in

October 2017

£8.6 billion

allocated

in Autumn

Statement 2015

up to2020-21

£3.5 billion

allocated for

2013-14 to

2015-16

£7.2 billion

additional funding

announced in

October 2018 for

2021-22 to 2022-23

£29 billion

Total amount the Ministry of Housing,

Communities & Local Government

has committed to the scheme

up to March 2023, to build up to

470,000homes

Source: National Audit Offi ce

Key milestones

Funding commitments

Scheme extensions

Policy changes

Total loaned

2013 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2048

Spring 2014

Scheme extended

to2020

2014

16 Part One Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

1.4 The Department designed the scheme to be straightforward to administer,

simple to understand, and easy for applicants to access. For example, the scheme is

not means-tested and is open to both first-time buyers and those who have owned

aproperty previously.

1.5 Demand for the scheme greatly exceeded initial expectations. The government

met demand by investing more money than originally planned in the scheme.

In2017-18, theDepartment invested £3.3 billion through the scheme, around 29%

oftheDepartment’stotal annual expenditure.

How the scheme works

1.6 The scheme is administered by Homes England, an executive non-departmental

public body sponsored by the Department, on behalf of the Department (Figure2).

The process of buying a new-build property through the scheme differs from a

traditional purchase (Figure 3 on pages 18 and 19). Under the scheme, Homes

England offers the buyer of a new-build property, costing up to £600,000, an equity

loan of up to 20% (40% in London since February 2016) of the purchase price.

Theloan supplements the buyer’s deposit, which the scheme requires to be at least

5% of the property price. The buyer obtains a repayment mortgage of, typically,

75%of the property’s value. Mortgages that are 75% or less of a property’s value

typically have alower interest rate and are more affordable.

1.7 The value of the loan changes to remain proportional to the property’s value.

Iftheproperty’s value increases, the value of the equity loan will increase in proportion.

When the buyer redeems the loan, either when they sell the property, remortgage or

choose to repay part or all of the loan, they will pay back more than they borrowed if

the property has increased in value. Conversely, if the property value falls, buyers will

pay back less than they borrowed. Buyers outside of London may repay either 50% or

100% of the current value of the equity loan at any time after the first year of owning their

home. InLondon, buyers can repay in up to four instalments, each at least 10% of the

home’s current market value, at any time after the first year. The loan must be paid back

in full on sale of the property, within 25 years, or in line with the buyer’s main mortgage

if this is extended beyond 25 years. The Department expects that most buyers will

redeem the equity loan early in the 25-year loan period to reduce the risk that they will

pay back significantly more than they borrowed if they keep the loan for longer. If a home

is repossessed, the mortgage lender gets their money back first because they are the

firstcharge on the property; the equity loan is the second charge.

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Part One 17

Figure 2 shows Roles and responsibilities for the Help to Buy: Equity Loan

Figure 2

Roles and responsibilities for the Help to Buy: Equity Loan

Source: Adapted from Comptroller and Auditor General,

The Help to Buy equity loan scheme, Session 2013-14, HC 1099, National Audit Offi ce, March 2014

The Department is responsible for the Help to Buy scheme, with Homes England and its agents, developers and

buyers playing important roles

Policy

Buyers

Funding and

commissioning

Service

providers

Register

Help to Buy

loan paid

directly

Issue

transaction

approvals

Receive

£315per

completed

sale

Loan

repayments

and interest

fees

Provide

information

on completed

sales

Register via

agent

Purchase

property

through a

registered

builder

Submit

application

Perform

affordability

checks

Repay

loans and

interest fees

Help to Buy agents

There are 7 regionally

based companies.

Perform the

affordability checks on

potential buyers and

process applications.

Mortgage

administrator – Target

Administers the loans

on behalf of Homes

England. Manages

redemptions and

interest fees.

Larger developers

Build new homes

Direct potential

purchasers toHelp

to Buy agents.

Smaller developers

Build new homes

Homes England

Responsible for delivering the scheme. Registers and contracts with house builders and

Help to Buy agents.

Makes the equity loan to the purchaser on the advice of the Help to Buy agent.

Buyers of new-build properties up to £600,000. Buyers provide a 5% deposit.

Help to Buy

loan paid

directly

Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government

Responsible for setting policy, funding and oversight of the scheme.

18 Part One Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

Figure 3 shows Help to Buy customer experience in England

Notes

1 Customer must not own a property at the point of fi nalising the equity loan. This is set to change to only fi rst-time buyers in 2021.

2 In London, customers can repay in up to four instalments, each at least 10% of the home’s current market value, at any time after the fi rst year.

Source: National Audit Office

Figure 3

Help to Buy customer experience in England

Prospective homeowners looking to use the equity loan have an additional application stage when purchasing their home

Customer finds a new-build property

1

and submits

reservation and property information forms to the

regional agent with the support of an independent

financial advisor.

Customers can apply for a 20% equity loan outside

of London towards a new-build property worth

up to £600,000 (40% equity loan in London).

Newregional prices will apply from April 2021.

Customer declined Help to Buy equity loan after

financial assessment by agent.

On selling the property, the customer repays the same

percentage value of the property as was loaned.

Alternatively, they can pay back the loan in full or in

two instalments at any time after the first year.

2

The loan must be repaid in full within 25 years or

in line with the buyer’s main mortgage if this is

extended beyond 25 years.

The customer begins paying equity loan interest

payments after 5 years, starting at 1.75% of the

equity loan and rising annually by Retail Price Index

+ 1%. Regardless of house price movements, the

interest fee repayments remain fixed to the original

equity loan price. In addition, the customer pays a

£1 monthly management fee from the first month.

These payments do not count towards repaying

theequity loan capital.

Authority to proceed issued by agent. The customer

can now submit a mortgage application and their

solicitor begins the normal conveyancing process.

Buyer provides deposit –

at least 5%.

Exchange and

completepurchase.

Pre-application Application

Purchase Post-purchase

FOR

SALE

SOLD

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Part One 19

Figure 3 shows Help to Buy customer experience in England

Notes

1 Customer must not own a property at the point of fi nalising the equity loan. This is set to change to only fi rst-time buyers in 2021.

2 In London, customers can repay in up to four instalments, each at least 10% of the home’s current market value, at any time after the fi rst year.

Source: National Audit Office

Figure 3

Help to Buy customer experience in England

Prospective homeowners looking to use the equity loan have an additional application stage when purchasing their home

Customer finds a new-build property

1

and submits

reservation and property information forms to the

regional agent with the support of an independent

financial advisor.

Customers can apply for a 20% equity loan outside

of London towards a new-build property worth

up to £600,000 (40% equity loan in London).

Newregional prices will apply from April 2021.

Customer declined Help to Buy equity loan after

financial assessment by agent.

On selling the property, the customer repays the same

percentage value of the property as was loaned.

Alternatively, they can pay back the loan in full or in

two instalments at any time after the first year.

2

The loan must be repaid in full within 25 years or

in line with the buyer’s main mortgage if this is

extended beyond 25 years.

The customer begins paying equity loan interest

payments after 5 years, starting at 1.75% of the

equity loan and rising annually by Retail Price Index

+ 1%. Regardless of house price movements, the

interest fee repayments remain fixed to the original

equity loan price. In addition, the customer pays a

£1 monthly management fee from the first month.

These payments do not count towards repaying

theequity loan capital.

Authority to proceed issued by agent. The customer

can now submit a mortgage application and their

solicitor begins the normal conveyancing process.

Buyer provides deposit –

at least 5%.

Exchange and

completepurchase.

Pre-application Application

Purchase Post-purchase

FOR

SALE

SOLD

20 Part One Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

Figure 4 Shows Illustrative annual interest payments for buyers using the scheme

1.8 The equity loan is interest-free for five years. From the start of year six,

HomesEngland charges buyers interest, initially at 1.75% of the original equity

loan’s value. Theinterest rate rises annually by 1% above the Retail Prices Index,

which equates to 1.82% in year seven based on current forecasts.

1

The buyer also

pays a management fee of £1 per month from the first year of homeownership.

Theinterestandmanagement fee payments do not count towards repaying the

equityloan capital(Figure 4).

1 As at April 2019, long-term Retail Prices Index is calculated as 3%.

Figure 4

Illustrative annual interest payments for buyers using the scheme

Buyers using the scheme begin to pay interest after the fi fth year of homeownership, starting at a

rate of 1.75% in year six and increasing by 1% above the Retail Prices Index each year after that

Property price

Year 6 Year 7 Year 8 Year 9 Year 10

£200,000

England (excluding London) £700 £728 £756 £788 £820

London £1,400 £1,456 £1,512 £1,576 £1,640

£300,000

England (excluding London) £1,050 £1,092 £1,134 £1,182 £1,230

London £2,10 0 £2,184 £2,268 £2,364 £2,460

£400,000

England (excluding London) £1,400 £1,456 £1,512 £1,576 £1,640

London £2,800 £2,912 £3,024 £ 3,152 £3,280

£500,000

England (excluding London) £1,750 £1,820 £1,890 £1,970 £2,050

London £3,500 £3,640 £3,780 £3,940 £4,10 0

£600,000

England (excluding London) £2,10 0 £2,184 £2,268 £2,364 £2,460

London £4,200 £4,368 £4,536 £4,728 £4,920

Interest rate 1.75% 1.82% 1.89% 1.97% 2.05%

Notes

1

A long-term Retail Prices Index estimate of 3% is used here.

2

The £1 monthly management fee is excluded from the calculation.

3

The calculation uses an equity loan proportion of 20% for England (excluding London) and 40% for London.

Source: National Audit Offi ce

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Part One 21

The future of the scheme

1.9 The Department forecasts that around 352,000 homeowners will have bought with

the support of the scheme by March 2021, with a total investment of around £22 billion

in cash terms. In October 2018, the government announced that a new scheme would

run from April 2021 to March 2023. The government will make available an additional

£7.2 billion, which it forecasts will support a further 110,000 households. This will take

the overall budget for the scheme to around £29 billion in cash terms. The Department

forecasts that this will support a total of around 462,000 households by 2023.

1.10 The new scheme will introduce restrictions to eligibility. Whereas former

homeowners can participate in the current scheme, only first-time buyers will be able

to take part in the new scheme. The Department will introduce regional caps on the

maximum property price, set at one and a half times the current average first-time buyer

purchase price for that region, with a maximum of £600,000 in London.

1.11 The scheme will end in March 2023 and the Department currently has no plans

to replace it. The Department told us that signalling the end of the scheme gives

developers enough time to plan for a regime without the scheme, to avoid a sudden

drop in new-build sales, and consequent reduction in housebuilding.

22 Par t Two Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

Part Two

The impact of the scheme

2.1 This part of the report examines how the Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme

(thescheme) has performed against its objectives, and who has benefited from it.

Italsolooks at the other consequences of the scheme, including for developers, and

thepotential impact of the scheme on new-build house prices.

Progress of the scheme

2.2 When it set up the scheme, the Department for Communities and Local

Government (now the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government)

(theDepartment) anticipated that it would support 74,000 property purchases across

thethree years 2013-14 to 2015-16, at an investment of £3.5 billion. The Department

initially expected that between 25% and 50% of sales would result in new homes

being built. From the outset, the scheme was more popular with potential buyers

thananticipated, supporting 81,000 property purchases over the first three years.

TheDepartment increased its investment in the scheme to meet demand. Based on

recent performance, it now expects the current scheme to support around 352,000

buyers by March 2021 and tohave invested just over £22 billion in cash terms.

2.3 As at December 2018, the scheme had supported around 211,000 property

purchases through loans totalling £11.7 billion (Figure 5). Outside London, participants

have typically bought properties with three or more bedrooms, and 11% of all sales

supported by the scheme have been flats. In London, participants have typically bought

properties with two beds, and 84% of sales have been flats. Almost all participants

outside London have taken out the full equity loan share of 20%, which has averaged

nearly £55,000 since the scheme started.

2

In 2018, over three-quarters of participants in

London took out the full equity loan share of 40%. Most properties (57%) have been sold

at £250,000 or under, although this proportion varies by region with the overall profile

and mix of transactions.

2 £55,000 includes properties in London. Excluding London, the average equity loan nationally was around £48,500 as at

December 2018.

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Par t Two 23

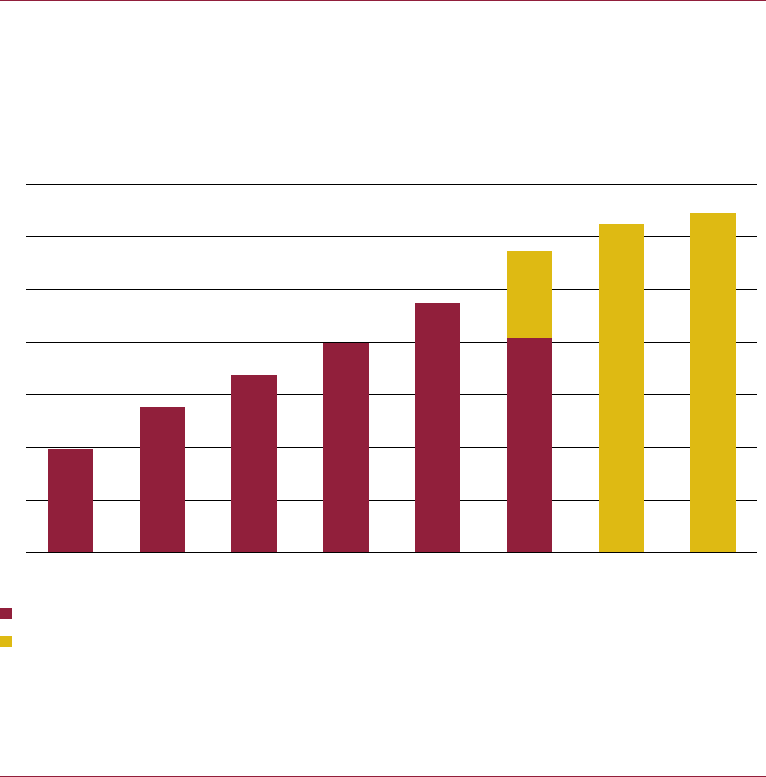

Figure 5 shows Total and forecast Help to Buy sales in England, 2013-14 to 2020-21

Achievement against the scheme’s aims

2.4 The scheme has two principal aims: to help prospective homeowners obtain

mortgages and buy new-build properties; and, through the increased demand for

new-build properties, to increase the rate of house building in England. The scheme has

no targets. The Department has commissioned two independent evaluations to assess

the additionality of the scheme: that is, the number of new-build sales and the number

of new properties built that would not have been built if the scheme did not exist.

Thefirst evaluation, published in February 2016, examined the scheme’s performance

toJanuary2015 and concluded that:

•

43% of buyers would not have been able to afford the same or similar property in

the new-build or existing markets without the scheme’s assistance; and

•

assuming these purchases are of properties that would not otherwise have been

built, the scheme resulted in 14% more new-build properties being built.

Figu

re 5

To

tal and forecast Help to Buy sales in England, 2013-14 to 2020-21

Completions (000)

The scheme has been used to support nearly 211,000 sales. Homes England for

ecasts that around

352,000 sales will have been made with support fr

om the scheme by April 2021

Help to Buy completions

Help to Buy completions – forecast

No

tes

1

Based on Homes England’s forecast as at December 2018.

2

Completion figures may not sum to exactly 211,000 due to time lags in updating forecasts for actual sales.

Sour

ce: National Audit Office analysis of data from Homes England

2013-14 2014-15 2015-16

2016-17 2017-18 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

19.6

27.7

33.7

39.8

47.5

62.1

64.3

41.0

16.1

24 Par t Two Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

2.5 The second evaluation, published in October 2018, examined the additionality of

the scheme between June 2015 and March 2017. It drew on a broader evidence base,

including a larger sample of buyers and a greater number of developers, compared with

the first evaluation. It concluded that:

•

37% of buyers could not have bought a property without the scheme, which

we estimate to be around 78,000 additional sales. This is the proportion of

homeowners who could not have bought without the scheme as a proportion of

total Help to Buy sales as at December 2018;

•

the scheme had resulted in 14.5% more new properties being built;

3

and

•

the scheme had enabled 79% of buyers to buy a property sooner than they would

otherwise have been able.

The buyers’ responses reflect their recollection of the situation at the time they bought.

They do not account for the possibility of the buyers’ circumstances changing to

enablethem to buy a similar property in the future.

2.6 Evaluating the impact of the scheme is difficult because there is not a group of

potential buyers for whom the scheme was not available, against whom the impact of

the scheme can be compared. We therefore examined the methods used to gather

evidence to evaluate the additionality of the scheme. We found that the methodology

of the evaluations, which were undertaken by experts in the fields of housing and

evaluation, was reasonable given the nature and design of the scheme, and the inherent

limitations of relying on responses in surveys to estimate additional house building.

Toassess the number of buyers who could not have bought without the support of the

scheme, the second evaluation surveyed a sample of 1,500 households that bought a

property through the scheme, using a series of questions. The evaluations assessed

the impact of the scheme and did not look at those people who did not go ahead or

were rejected from the scheme. Stakeholders from the housing sector stated to us in

interviews that they regarded the evaluations as comprehensive and robust, and the

calculation of additionality was reasonable.

3 The second evaluation calculated additionality differently to the first evaluation, including a further sub-question to

assess participants’ ability to buy a smaller property than the one they bought.

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Par t Two 25

Figure 6 shows New-build and existing-build property sales in England, 2000 to 2017

2.7 Since the scheme started, new-build sales have increased from 61,357 in 2012-13

to 104,245 in 2017-18. Over the period April 2013 to September 2018, 38%of new-build

purchases have been supported by the scheme, equating to around 4% of all housing

purchases. New-build sales as a proportion of total property sales has increased

from around 9% in 2014, the first full year of the scheme, to more than 12%in2017.

Totalproperty sales have levelled off during this time, following a sharp increase

in2013 (Figure6).

4

Bodiesrepresenting developers and lenders told us the scheme

had helped increase public confidence in housebuilding and house buying generally,

andthat the scheme had raised the profile of new-build properties with those looking to

buy. HomesEngland told us the scheme has given local authorities greater confidence

that planning consents they grant will be built out by developers, although we have

notbeenable to assess this effect.

4 These data are based on Land Registry transactions and underestimate the actual number of new-build sales because

Land Registry data do not identify new-build sales within developments of five or less properties. Land Registry data

uploads are also subject to long delays. At April 2019, Land Registry data indicated that new-build sales represented

12.5% of total sales over 2018.

Figu

re 6

Ne

w-build and existing-build property sales in England, 2000 to 2017

Property sales

No

te

1

Data accessed in April 2019. Office for National Statistics data for new-build sales and existing-build property sales originate from

the Land Registry which is subject to long delays.

Sour

ce: National Audit Office analysis of Office for National Statistics data on new-build sales and existing dwelling sales

The pr

oportion of new-build property sales has increased since the scheme began in 2013

0

200,000

400,000

600,000

800,000

1,000,00

0

1,200,00

0

1,400,00

0

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Total property sales

Existing-build property sales

New-build property sales

26 Par t Two Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

Impact of the scheme

2.8 At local authority level, areas where housing is less affordable have experienced

lower proportions of sales supported by the scheme (Figure 7 and Figure 8 on

page28).

5

Local authorities of lower affordability generally have higher proportions of

properties for sale at prices above the maximum of £600,000 allowed by the scheme.

In 2017, 68% of properties in London sold for £600,000 or less, compared with 97%

for the rest of England. The Department set a relatively high cap on property prices

at £600,000 so that almost all new-build properties would be eligible for the scheme.

Across England, in 2013, over 96% of all new-build properties sold for £600,000 or less.

Regional variation in sales supported by the scheme

2.9 London has experienced the lowest take up of the scheme. Following the increase

in the maximum loan allowed in London in February 2016, from 20% to 40% of the

sale price, the proportion of new-build homes sold with the support of the scheme

increased, from around 12% to 26%. However, the proportion of homes bought through

the scheme in London is still lower than in the rest of England. Between the start of the

scheme and December 2015, excluding London, the take up of the scheme was 34%,

and ranged from 29% of new-build sales in south-east England to 42% in north-east

England. Between January 2016 and September 2018, this increased to 46%, and

ranged from 42% in south-west England to 51% in the East Midlands.

6

Potential

homeowners in London face generally higher sale prices than the rest of England.

The average price in London in 2018 was over £450,000, 66% more than the average

purchase price across the rest of England (around £272,000). This price equates to an

equity loan of over £180,000 should the buyer take out the full 40%. After five years, a

typical London buyer will pay nearly £3,000 in interest annually, compared with under

£1,000 outside London.

5 Less affordable areas as defined by the Office for National Statistics, where the ratio of median house price to

medianearnings is higher.

6 Proportion of new-builds sold with the scheme based on data as at September 2018.

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Par t Two 27

Figure 7 shows Help to Buy sales as a proportion of total new-build sales, April 2013 to September 2018

Figure 7

Help to Buy sales as a proportion of total new-build sales, April 2013 to September 2018

Notes

1

New-build sales data between April 2013 and March 2018 taken from Offi ce for National Statistics (ONS) new-build sales dataset. New-build sales data

between April 2018 and September 2018 taken from Land Registry price-paid data. This is to account for the ONS new-build sales dataset which is

reported as rolling year.

2

Land Registry data accessed in April 2019.

3

All new-build properties are included in this analysis. Removal of non-qualifying property, ie property valued over £600,000, would increase the

HelptoBuy proportion, particularly in London.

4

Isles of Scilly excluded as no properties have been sold there using the scheme.

Source: National Audit Offi ce analysis of data from Homes England, Land Registry price-paid data, and Offi ce for National Statistics data on new-build sales

Proportion of Help to Buy properties

to new-build completions

Over 60% new-build properties

soldwith Help to Buy

45%–59% new-build properties

soldwith Help to Buy

30%–44% new-build properties

soldwithHelp to Buy

15%–29% new-build properties

soldwithHelp to Buy

Less than 15% new-build properties

sold with Help to Buy

Regions

London

There is wide variation in the take up of Help to Buy as a proportion of all new-build sales across England

28 Par t Two Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

Figure 8 shows Median property prices and proportion of Help to Buy sales for local authorities in England, 2013 to 2018

No

tes

1

Sales data as at September 2018.

2

Isles of Scilly excluded as no properties have been sold there using the scheme.

Sour

ce: National Audit Office analysis of data from Homes England, Office for National Statistics on affordability, and Ministry of Housing,

C

ommunities & Local Government data on new-build sales

Figu

re 8

Median pr

operty prices and proportion of Help to Buy sales for local authorities

in Englan

d, 2013 to 2018

Median house price (£)

Local authorities with mor

e expensive properties have generally experienced a lower proportion of Help to Buy sales

Proportion of new-build sales sold with Help to Buy (%)

0

200,000

400,000

600,000

800,000

1,

000,000

1,

200,000

1,

400,000

1,

600,000

010203040506070809

01

00

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Par t Two 29

Figure 9 shows First-time buyer loans in England, 2000 to 2017

First-time buyers

2.10 As at December 2018, 81% of all buyers supported by the scheme have been

first-time buyers. First-time buyers using the scheme have larger household incomes

than the typical first-time buyer in each region and nationally (median income of

£48,000in England in 2017 for those using the scheme, compared with £42,400 for

all first-time buyers).

7

Some 61% of first-time buyers using the scheme bought with a

5% deposit. The proportion of first-time buyers across the whole housing market has

increased from a low of under 30% in 2003 and 2004, to make up nearly half of the

totalmarket in 2017 (Figure 9).

7 This is a comparison between Help to Buy data and UK Finance data on lending to first-time buyers. UK Finance data

do not exclude those first-time buyers purchasing an existing-build property.

Figu

re 9

Firs

t-time buyer loans in England, 2000 to 2017

Pr

oportion of total loans (%)

Sour

ce: National Audit Office analysis of data from UK Finance

First-time buyers now make up nearly half of all mortgage loans

0

10

20

30

40

50

80

90

70

60

10

0

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Proportion of loans which are for first-time buyers

30 Part Two Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

Diversity

2.11 Although not an objective of the scheme, it has been taken up by a higher

proportion of black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) buyers compared with

first-timebuyers generally. The Department’s second evaluation found that a quarter

of first-time buyers who have bought with the support of the scheme are from BAME

backgrounds. This is compared with less than a fifth (15%) of allfirst-time buyers from

BAME backgrounds nationally. The evaluation also found that 63% of first-time buyers

usingthescheme were aged 34 and under.

Other consequences of the scheme

Scheme participants

2.12 As at December 2018, 19% of buyers were people who had previously owned

a property, equating to nearly 40,000 households. Of these former homeowners,

39%have bought with a deposit of more than 10% of the property value, compared

with 17% of first-time buyers. On average, former homeowners have larger households

than first-time buyers, have larger household incomes and purchase more expensive

properties with more bedrooms through the scheme with a larger deposit. The second

scheme evaluation found that 31% of homeowners could have bought a property they

wanted without the support of the scheme.

2.13 Scheme participants have generally bought more expensive properties than

the typical first-time buyer, using the equity loan to support the purchase (Figure10).

Thisdifference is greater in regions of greater affordability. Buyers took out mortgages

and equity loans that together were typically around four and a half times their

annual income (increasing to over six times in London). In contrast, first-time buyers

generally took out mortgages that were three and a half times their annual income.

The HomeBuilders Federation told us that developers have responded by building

more properties of all types. Properties built with three or more bedrooms have

becomeanincreasingly common feature of the market (Figure 11 on page 32).

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Par t Two 31

Figure 10 shows Average price paid for a new-build property by first-time buyers with and without support from the Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme in England, 2018

Average price paid

by first-time buyers

for new-build

properties

157,558 241,584 419,980 109,644 133,959 259,036 208,751 160,086 135,963

Average price paid

by first-time buyers

for new-build

properties using

the Help to Buy

scheme

235,470 299,682 449,443 182,445 215,351 338,395 263,301 233,13 5 201,971

Note

1

Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government data for all fi rst-time buyers are taken as an annual average of each month’s average purchase price.

Source: National Audit Offi ce analysis of Help to Buy data from Homes England and the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government data on fi rst-time buyers

Figu

re 10

A

verage price paid for a new-build property by first-time buyers with and without support from the

Help

to Buy: Equity Loan scheme in England, 2018

Price paid (£)

Scheme participants ar

e buying more expensive properties, on average, than those not using the scheme

0

150,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

400,000

450,000

500,000

200,000

100,000

50,000

Yorkshire

and The

Humber

West

Midlands

South

West

South

East

North

West

North

East

LondonEast

England

East

Midlands

32 Par t Two Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

Figure 11 shows Number of bedrooms in new-build properties in England, 2010-11 to 2017-18

Figu

re 11

Number

of bedrooms in new-build properties in England,

20

10-11 to 2017-18

Pr

oportion of properties built (%)

Pr

operties with three or more bedrooms make up a greater proportion of the new-build

market year on year since 2011-12

1 bedroom

2 bedrooms

3 bedrooms

4 or more bedrooms

No

te

1

Figures may not sum due to rounding.

Sour

ce: National Audit Office analysis of the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government’s data on

house

building: new dwellings

0

10

20

40

60

80

10

0

90

70

50

30

2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17 2017-18

33

7

27

34

32

8

27

30

8

28

34

33

28

7

31

34

25

6

33

36

24

6

35

35

23

6

35

36

22

6

36

36

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Par t Two 33

2.14 The Department is aware that some scheme participants have not needed an

equity loan to buy their property. It accepts that this is a consequence of the scheme

being demand-led and with no restrictions on eligibility based on household income.

As at December 2018, a total of 4% of the 211,000 scheme participants had household

incomes over £100,000, a proportion that has increased each year from 3% in 2013 to

5% in 2018. In 2018, around 2% of scheme participants had incomes in the upper tenth

percentile of household incomes nationally.

8

Ten per cent of scheme participants had

household incomes over £80,000 (or over £90,000 in London), the income threshold set

for another of the Department’s schemes to support Home Ownership.

9

The Department

told us that allowing unrestricted access to the scheme has made it simple to administer

and has maximised the number of participants, thereby adding to the increased

confidence the scheme has instilled throughout the housing market.

New-build premium

2.15 New-build properties typically sell at a higher price than existing properties with

similar characteristics, reflecting the fact that they have yet to be lived in. This ‘new-build

premium’ has typically averaged around 20% over time. It dropped to around 15% after

the financial crash of 2008, began to rise again from 2010 and has since risen to around

20%.

10

The scale of the new-build premium varies for property type and regionally, for

example in London new-build properties typically sell with only a small, if any, new-build

premium. Buyers who want to sell their property soon after they have bought it might

find they are in negative equity for a period of time, depending on the scale of the

premium at the time of purchase and the subsequent change in house prices locally.

2.16 We did not find a relationship when we compared the size of the new-build

premium of similar properties within a postcode district with the proportion of

propertiesbought with the support of the scheme. However, the scheme has

contributed to increased sales of new-build properties. Between the beginning of the

scheme and December 2018, prices paid for new-build properties increased by 41%

in England, compared with a 38% increase for existing properties. The increase in the

new-build premium since 2010 is likely a response to changes in wider economic and

housing market conditions, which the scheme has contributed to since 2013.

8 Upper tenth percentile household income here classed as Office for National Statistics’ estimate of UK all households’

gross income in 2017-18, calculated at £124,725.

9 These household incomes are the current (as at April 2019) household income caps for the Department’s Shared

Ownership scheme.

10 New-build premium calculated as new-build property purchase prices compared with existing builds nationally,

usingUK House Price Index. This calculation does not control for the mix of property sold.

34 Par t Two Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review

Help to Buy premium

2.17 Analysis by other commentators has found that buyers of Help to Buy properties

pay an additional premium, on top of the new-build premium, quoting figures of between

a 5% and 20% premium.

11

These figures originate from four different pieces of research

that compare the average price of properties bought with the support of the scheme

with those bought without. We found that the research did not directly compare

like-for-like properties and therefore the differences found will in part reflect differences

in the average size or other characteristics of properties bought with and without the

scheme. For this report, we compared prices paid by buyers of similar properties

(sametype of property, similar size of property by square metre, same postcode,

andbought within the same month) and found that the difference between buyers

whobought with and without the support of the scheme was less than 1%.

2.18 We have not been able to quantify other potential incentives for buyers of

new-buildproperties, such as a developer supplying white goods or paying solicitors’

fees. Thescheme restricts incentives to 5% of the purchase price, whereas there are

no restrictions on incentives to those buying without the scheme. Scheme participants

canalso achieve savings elsewhere, for example:

•

lower interest rates on lower loan-to-value mortgages;

•

savings from rent foregone by buying a property sooner; and

•

no interest paid on the equity loan for five years.

Developers’ engagement with the scheme

2.19 By December 2018, over 2,000 developers had registered with the scheme.

Fivedevelopers account for over half of all properties sold with the support of the

scheme. More small and medium-sized developers have joined the scheme than

joinedprevious schemes with similar aims. The Department designed Help to Buy so

that it was more accessible to smaller developers, as there are no criteria over who can

apply for funding, and there is no requirement to compete with other firms to develop

sites. The 2017 independent evaluation found that around four-fifths of the developers

registered with the scheme had made 10 or fewer transactions. The Department’s

evaluation also included a survey of small and medium-sized developers, which found

that fewer than 20% of the 65respondents were registered with the scheme. The main

reason given for not registering was that they were not planning to build properties

that would be eligible for Help to Buy loans. Administrative costs were not cited as a

major constraint to joining the scheme. However, a group of small and medium-sized

developers told us that there is a large amount of paperwork involved in registering

with the scheme, which some found difficulttodo because of the amount of time

andeffortrequired.

11 Research by property quotes and home-moving company Reallymoving quoted a premium of 12% (www.reallymoving.

com/news/april-2019/help-to-buy-premium-12-percent); research by property sales portal Okaylah quoted a premium

of more than 20% (www.propertyindustryeye.com/by-a-quarter-if-they-use-help-to-buy); The Times quoted a premium

of 15% per square metre between comparable properties that are and are not eligible (www.thetimes.co.uk/article/

help-to-buy-boom-could-leave-a-generation-in-negative-equity-ddtb68skb); Stockdale research in 2017, stating that

there is potentially a premium of up to 5%, is not available online.

Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme – progress review Par t Two 35

Figure 12 shows Proportion of Help to Buy sales by developer in England, 2013 to 2018

2.20 Developers interviewed through the Department’s evaluation said that they found

the scheme hard to use if they were doing so irregularly. One Help to Buy agent told

us that they spend more time supporting smaller developers, for example supporting

them to apply to register with the scheme and subsequently processing loans.

The Department’s evaluation found that larger developers were better equipped to

resource the scheme’s administration. For example, larger developers can manage

their own equity loan payments, whereas smaller developers are more likely to rely

onaHelptoBuy agent for support.

2.21 Of the six developers in England that build most properties, five sell a greater

combined total of properties with the support of the scheme than the remaining

developers on the scheme (Figure 12). In 2018, these five sold between 36% and

48%of their properties with the support of the scheme.

12

The sixth developer from

these top six tends to build high-value properties that sell for more than the upper price

limit of the scheme and therefore sells fewer properties with the support of the scheme.

Thescheme has supported these five to increase the overall number of properties they

sell year on year, thereby contributing to the increases in their annual profits and share

price (Figure 13 overleaf), a consequence of the scheme that has been extensively

commented upon in the media. Since the start of the scheme, total combined

housingcompletions for these five developers has increased by over a half.

12 Data as declared by developers in their annual reports. These data include all activity, which includes activity in both

Wales and Scotland for most of the top five developers.

Figure 12

Proportion of Help to Buy sales by developer in England, 2013 to 2018

Persimmon, 14.8%

Barratt, 13.3%

Taylor Wimpey, 11.9%

Bellway, 6.7%

Redrow, 3.7%

Remaining developers, 49.6%

Note