How Financial Planners Actually

Do Financial Planning (2023)

Volume 1, 2023

The Kitces Report

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

About The Authors

Lead Researcher

Dan Inveen

CFA

Biography

For more than two decades Dan has

directed a broad spectrum of industry

executives toward a better understanding

of how to succeed in the financial

advisory marketplace. He has worked

with broker-dealers, asset managers,

leading RIAs, and every major industry

custodian, helping to identify emerging trends in the distribution and demand for

financial advice as well as best practices in firm management.

Once part of the Moss Adams consulting team that pioneered the field of advisor

“practice management” in the mid-2000’s, Dan later co-founded his own boutique

industry research and consulting firm, FA Insight. After just seven years he successfully

sold the firm to TD Ameritrade, one of the country’s leading providers of brokerage and

custody services.

His research and consulting experience covers a broad range of issues affecting financial

advisors, including strategic planning, organizational design, compensation, operations,

and M&A. For over a decade Dan led the production of the FA Insight Annual Study of

Advisory Firms, a leading resource of critical intelligence for financial advisory firms as

well as the institutions that serve them.

Dan began his career as a government economist, including several years leading the

Bureau of Economic Research in the U.S. Virgin Islands, before overseeing the marketing

research function for Russell Investments. Dan holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in

economics from the University of Washington and is a CFA Institute charter holder.

Chief Financial

Planning Nerd

Michael Kitces

MSFS, MTAX, CFP®, CLU, ChFC,

RHU, REBC, CASL

Biography

Michael Kitces is the Chief Financial

Planning Nerd at Kitces.com, dedicated

to advancing knowledge in financial

planning and helping to make financial

advisors better and more successful,

and the Head of Planning Strategy at

Buckingham Wealth Partners, an independent RIA with more than $50 billion of assets

under management, that provides private wealth management to consumers and

turnkey asset management platform services to advisors.

In addition, he is a co-founder of the XY Planning Network, AdvicePay, New Planner

Recruiting, fpPathfinder, and FA BeanCounters, the former Practitioner Editor of the

Journal of Financial Planning, the host of the Financial Advisor Successpodcast, and the

publisher of the popular financial planning continuing education blog Nerd’s Eye View.

Beyond his website and many businesses, Michael is an active writer and speaker

across the industry, and has been featured in publications including Financial

Planning, the Journal of Financial Planning, Journal of Retirement Planning, Practical

Tax Strategies, and Leimberg Information Services, as well as The Wall Street Journal,

BusinessWeek, CNBC PowerLunch, NBC Nightly News, and more. In addition, Michael

has co-authored numerous books, including “The Annuity Advisor” with John Olsen

(now in 5th edition), and “Tools & Techniques of Retirement Income Planning” with

Steve Leimberg and others.

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023 About The Authors | 2 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023 About The Authors | 3 of 67

Senior Research Nerd

Meghaan Lurtz

Ph.D., FBS™

Biography

Meghaan Lurtz, Ph.D., FBS™ is a Profes-

sor of Practice at Kansas State Univer-

sity where she teaches courses for the

Advanced Financial Planning Certificate

Program, a lecturer at Columbia Univer-

sity where she teaches Financial Psychol-

ogy, and an on-staff writer and researcher

of financial psychology at Kitces.com.

Her research interests vary as she studies both practitioners of financial planning

as well as financial planning and financial therapy practices and interventions. Her

research and expertise have been featured in Journal of Financial Planning, Journal of

Consumer Affairs, Financial Planning Review, Wall Street Journal, BBC, Million Dollar

Roundtable, and New York Magazine. She has also contributed chapters to the CFP

Board’s textbook, Client Psychology.

Meghaan is a past President and current board member for the Financial Therapy

Association and Financial Psychology Institute Europe.

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

About The Authors

FEATURED IN:

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

Table Of Contents

About The Authors .................................................................................2

Executive Summary ...............................................................................7

Key Findings .................................................................................................................................................... 7

‘The Plan’ Is Taking A Second Seat To Ongoing Planning ......................................................... 7

Financial Planning Increases In Complexity..................................................................................... 7

Financial Planning Technology Struggles To Keep Pace ........................................................... 8

Odds Favor Advisors Who Gain Control Over Their Time ........................................................... 8

Mid-Size Service Teams With 3–4 People Are The Sweet Spot ............................................... 8

Capability To Serve Affluent Clients Eases The Path To Higher Productivity .................. 9

Capturing Opportunity By Taming Time With Moderation ...................................................... 9

Introduction ...........................................................................................10

Study Objectives And Coverage ............................................................................................................10

Survey Participants And Methodology ...............................................................................................11

Figure 1. Summarizing Survey Respondents .......................................................................................................11

It’s About Time ...................................................................................... 12

Figure 2. Hours Worked By Role ..................................................................................................................................12

Bigger Teams Lead To Busier Advisors ..............................................................................................12

Figure 3. Senior Advisor Hours Worked By Size Of Service Team .....................................................13

Commission Business Requires Greater Time Investment ......................................................13

Figure 4. Senior Advisor Hours Worked By Channel ...................................................................................13

Advisor Hours And Revenue ...................................................................................................................14

Figure 5. Senior Advisor Hours Worked By Revenue Per Advisor .................................................... 14

Where Does Time Go? ...............................................................................................................................14

Figure 6. Time Allocation By Front, Middle, And Back Office ...............................................................15

Figure 7. Time Allocation By Specific Activity ...................................................................................................15

Optimizing The Senior Advisor Role .................................................................................................... 16

Figure 8. Senior Advisor Time Allocation By Revenue Per Advisor (Front, Middle,And

Back Office) ....................................................................................................................................................................................16

Figure 9. Senior Advisor Time Allocation By Revenue Per Advisor (Specific Activities) ....17

The Planning Service Team ..............................................................18

Team Size And Composition ...................................................................................................................18

Figure 10. Service Team FTE Range ........................................................................................................................... 18

Figure 11. Revenue Per Advisor By Team Size .................................................................................................... 18

Figure 12. Revenue Per Team Member By Team Size ..................................................................................19

Figure 13. Frequency Of Roles Used ...........................................................................................................................19

Figure 14. Roles Teams Use By Team Size .............................................................................................................19

Figure 15. Typical Service Team Structure By Team Size ......................................................................... 20

External Resources .....................................................................................................................................20

Figure 16. Reliance On External Support To The Team ............................................................................. 20

Figure 17. Reliance On External Support By Frequency Of Roles Used ......................................... 21

Figure 18. Reliance On External Support By Channel And Support Type .................................... 21

Team Time Per Client ................................................................................................................................ 22

Figure 19. Total Team Time Per Client By Business Channel ................................................................22

Figure 20. Total Team Time Per Client By Client Size..................................................................................22

Figure 21. Total Team Time Per Client By Revenue Per Advisor .........................................................23

A Process Of Compromises .................................................................................................................... 23

Financial Plan Development ........................................................... 24

Putting Plans In Context .......................................................................................................................... 24

Figure 22. Planning “Intensiveness” By Revenue Source ........................................................................ 24

Figure 23. When Clients Are Provided Financial Plans ..............................................................................25

Figure 24. Plan Update Frequency ............................................................................................................................25

Planning Vs Plans........................................................................................................................................ 25

Depth And Breadth Of Financial Plans ............................................................................................ 25

Figure 25. Components Included In Financial Plans .................................................................................. 26

Figure 26. Plan Breadth ..................................................................................................................................................... 26

Figure 27. Trends In Plan Breadth (2018-2022) ................................................................................................ 26

Plan Approach ..............................................................................................................................................27

Figure 28. Primary Approach To Plan Development ...................................................................................27

Figure 29. Primary Method For Presenting Plan Results ........................................................................ 28

Financial Plan Preparation Time .......................................................................................................... 28

Figure 30. Service Team Time To Prepare A New Plan By Breadth ................................................ 29

Table Of Contents | 4 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

Figure 31. Service Team Time To Prepare A New Plan By Approach ............................................. 29

Figure 32. Service Team Time To Prepare A New Plan By Revenue Source ............................ 29

Figure 33. Days From Client Sign-On To Implementation By Plan Breadth ........................... 30

Working With Clients - Year One .................................................... 31

Year One Time ...............................................................................................................................................31

Figure 34. Year 1 Time Allocation Per Client By Activity..............................................................................31

Figure 35. Average Year 1 Time Per Client By Activity (2018-2022) .....................................................31

Figure 36. Year 1 Time Allocation Per Client By Activity By Team Role .........................................32

Figure 37. Year 1 Senior Advisor Hours Per Client By Activity By Team Size .............................. 33

Year One Meetings – Overview ............................................................................................................. 33

Figure 38. Client Meetings To Complete The Financial Planning Process ................................33

Year One Meetings – Schedule of Coverage ................................................................................... 34

Figure 39. New Client Planning Process (Typical Meeting Flow) ...................................................... 34

Year One Meetings – Format ................................................................................................................. 35

Figure 40. Share Of Meetings By Format And Meeting Order ............................................................ 35

Working With Clients - Ongoing ................................................... 36

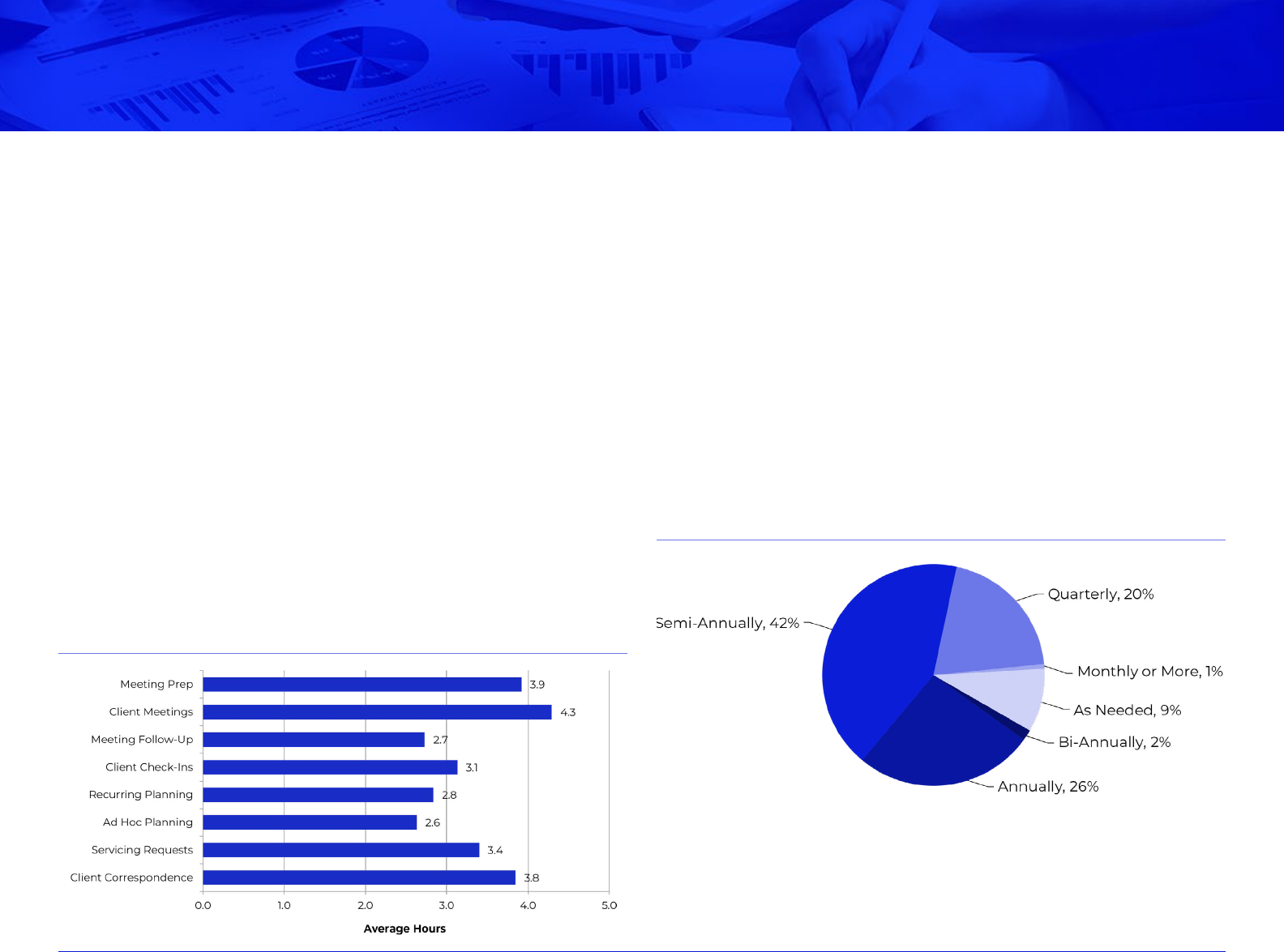

Figure 41. Average Annual Time Per Ongoing Client By Activity .......................................................36

Figure 42. Typical Meeting Frequency With Ongoing Clients .............................................................36

Practice Lifecycle ........................................................................................................................................37

Figure 43. Ongoing Client Touchpoints Per Year By Client Size ........................................................37

Figure 44. Distribution Of Ongoing Client Touchpoints By Type ....................................................37

Client Size Or Season? ..............................................................................................................................38

Relationship Type – Transactional Or Relationship Focused .................................................. 38

Figure 45. Ongoing Client Touchpoints Per Year By Revenue Source ........................................ 38

Ongoing Client Work – Conclusion ..................................................................................................... 38

Tools Supporting Plan Production ................................................ 39

Financial Planning Software Tools Overview ................................................................................. 39

Figure 46. Software Used To Produce Financial Plans ...............................................................................39

Figure 47. Per Plan Team Hours By Software Type Used ........................................................................39

Third-Party Planning Applications ..................................................................................................... 40

Figure 48. Third-Party Financial Planning Software Usage ..................................................................40

Figure 49. Third-Party Financial Planning Software Satisfaction .....................................................40

Figure 50. Third-Party Financial Planning Software (Usage vs. Satisfaction) ........................... 41

Table Of Contents | 5 of 67

eMoney ............................................................................................................................................................. 42

MoneyGuide ................................................................................................................................................... 43

RightCapital ...................................................................................................................................................43

NaviPlan .......................................................................................................................................................... 44

Orion Financial Planning .........................................................................................................................45

MoneyTree ......................................................................................................................................................46

Asset-Map .......................................................................................................................................................46

Specialty Financial Planning Applications ......................................................................................47

Figure 51. Specialized Software Usage ...................................................................................................................47

Figure 52. Specialized Tax Software .......................................................................................................................... 48

Figure 53. Specialized Social Security Software ..............................................................................................48

Charging For Plans And Financial Advice In General .............49

Pricing Overview .........................................................................................................................................49

Figure 54. Majority Revenue Source ........................................................................................................................49

Figure 55. Number Of Different Charging Methods Used ..................................................................... 49

Figure 56. Typical Client Affluence By Charging Method ....................................................................... 50

Typical AUM Fee Levels ............................................................................................................................50

Figure 57. Median Revenue As A Percentage Of Assets Managed ................................................. 50

Structuring Graduated Fee Schedules ............................................................................................... 51

Figure 58. Typical Blended Tier Fee Structure (Based On 4-Tier Median) ................................... 51

All-In Fees Including The Underlying Cost Of Investing ............................................................51

Figure 59. Expense Ratios For Underlying Client Funds By Advisor Channel ..........................51

Figure 60. All-In Fee By Advisor Channel By Portfolio Size (Moderate Risk Profile) ...........52

Retainer Fee ................................................................................................................................................... 52

Figure 61. Distribution Of Typical Annual Retainer Fee .............................................................................52

Hourly Charges ............................................................................................................................................. 53

Figure 62. Extent Of Variance For Retainer Fees ............................................................................................53

Figure 63. Distribution Of Hourly Planning Fees ............................................................................................53

Paying For Financial Plans ...................................................................................................................... 53

Figure 64. Typical Charging Methods For Financial Plans ...................................................................... 53

Figure 65. Median AUM Fee (Plan Bundled Vs Unbundled) ................................................................ 54

Standalone Project Planning Fees ......................................................................................................54

Figure 66. Distribution Of Fees For Standalone Plan ................................................................................. 54

Figure 67. Typical Standalone Plan Fee By Plan Breadth ........................................................................ 55

Plans By The Hour ....................................................................................................................................... 55

Figure 68. Distribution Of Cost For Plan Based On Hourly Rate 55

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

Planning For Success ......................................................................... 56

Figure 69. Advisor Productivity By CFP And Experience ......................................................................... 58

Figure 70. Advisor Productivity By Designations ........................................................................................... 58

What Does It All Add Up To? ........................................................... 59

Figure 71. Income By Role .................................................................................................................................................59

Figure 72. Senior Advisor Income By Experience .......................................................................................... 60

Figure 73. Senior Advisor Income By Service Team Size ..........................................................................60

Figure 74. Senior Advisor Income By Practice Structure ..........................................................................61

Figure 75. Senior Advisor Income By Majority Revenue Source ..........................................................61

Conclusion ............................................................................................. 62

Appendix ................................................................................................ 63

Financial Planning Software Detail Ratings ...................................................................................63

Study Terms ................................................................................................................................................... 65

Table Of Contents | 6 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

Executive Summary

Key Findings

• Despite a decade of naysayers claiming that financial advisors would be replaced

by ‘robots’ who can provide financial planning advice and implement portfolios, in

reality, the ongoing pressure of technology is leading financial advisors to do more

financial planning and go even broader and deeper in their financial planning

process.

• In turn, though, the work and service demands of doing more financial planning for

clients are leading to several additional shifts that repeatedly arose throughout our

research, including the ‘levelization’ of financial planning engagements over time

(to reduce the upfront burden with new clients and show ongoing value to clients

paying ongoing fees), the use of technology – not to make financial planning more

efficient but more effective, and the use of (the right-sized) teams to scale up the

efficiency of senior advisors.

• Notwithstanding the drive towards technology to improve advisor efficiency, we

found that adding staff support by growing a (3–4 person) team is a far greater

driver of productivity. However, one of the greatest predictors of advisor productivity

is simply the advisor’s ability to attract and retain more affluent clients who pay

higher fees and compensate the advisor more for their time and expertise, which

happens as advisors specialize, pursue advanced degrees and designations, and

gain years of experience in managing client relationships and delivering advice.

‘The Plan’ Is Taking A Second Seat To Ongoing Planning

• In the past year, the typical financial advisory team developed a new plan or

updated an existing one for over half of its clients (53%). However, most of their work

on plans, 71%, involved updates for ongoing clients. Financial planning work isn’t just

about ‘the plan’ anymore, as planning is increasingly both ongoing and dynamic as

more advisors build a base of recurring-revenue clients to whom they must show

their ongoing value.

• Even for new relationships, constructing The Plan only accounts for a minority of

the time that teams spend per client. Hours spent analyzing and evaluating the

new client’s financial status, developing recommendations, and then preparing

deliverables accounted for just ⁄ of the total time a team typically commits in the

first year of the relationship. More broadly, advisors are increasingly shifting from

delivering ‘The Plan’ to delivering financial plans more collaboratively, or making

planning more about the multi-meeting process than delivering The Plan at all (with

1-in-7 survey respondents spending above-average time on planning analysis but

below-average time on preparing and delivering the plan because their time was

spent more on the Process than the Plan itself).

Financial Planning Increases In Complexity

• Financial planning is becoming more complex. Most advisors, 54%, now cover 13 or

more financial topics in a typical client plan. Planning breadth is up from previous

related Kitces Research studies conducted in 2018 and 2020 when fewer than 40%

of advisors offered plans at that level of detail. The extent to which advisors prepare

custom-written financial plans for clients is also on the increase.

• As a result, the total time a team allocates to a financial planning client is on the rise.

The typical service team devoted 29 hours per client in the first year of a relationship

and 21 hours in subsequent years. After falling some as a result of the pandemic,

average first-year client time increased 13% from 2020 to 2022. The jump was

largely driven by a rise in time devoted to plan development, implementation, and

monitoring, which collectively was up more than 3 hours per client versus 2020.

• Despite fees holding mostly constant, signs are that advisors will continue to face

pressure to do more to substantiate and earn those fees. Of those advisors whose

clientele is predominantly 55 years or older, about half prepare Extensive plans for

their clients (13 or more topics). In contrast, ⁄ of those advisors serving a younger

client base prepare plans at this level of detail, suggesting a new generation of

clients that expects even more from the financial planning they get from their

advisors.

Executive Summary | 7 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

Financial Planning Technology Struggles To Keep Pace

• As advisors trend toward an increasingly greater level of comprehensiveness in their

planning, providers of financial planning software appear to be struggling to keep

up. While 90% of advisors rely on third-party comprehensive financial planning

applications, these programs rarely meet all the advisor’s technology needs for

planning. Of those advisors who used third-party comprehensive applications, nearly

⁄ further supported their planning work with either Word or Excel, and nearly half

needed specialized planning software to address specific needs such as planning

for taxes, retirement distribution planning, or Social Security, that aren’t covered

sufficiently by their general financial planning software.

• Given the trend towards greater depth and breadth in financial planning, the most

comprehensive planning tools (including RightCapital and eMoney) are winning

market share, though those applications with a strong portal and client-facing

experience in general (e.g., Orion Financial Planning and Asset-Map) appear to have

a steady (albeit niche) hold in the market.

Odds Favor Advisors Who Gain Control Over Their Time

• The challenge of client demand for increased depth and breadth in financial

planning, however, can be – and is being – overcome. In the face of advisors offering

ever more comprehensive plans, the median direct time for plan preparation,

including evaluating the client’s status and preparing the deliverable, has not

increased in at least 4 years. Since 2018 financial plan preparation time has held

steady at 10 hours.

• Growing adoption of the collaborative approach toward planning is helping to

facilitate advisors’ ability to better control planning time. Nearly half of advisors now

use planning software as a collaborative tool, developing plans with the client live

in ‘real time’. This compares to only about ⁄ of advisors just 4 years ago. At 8 hours

in typical prep time, collaborative plans are 2 hours below what is the norm across

all planning approaches. Overall, we find that fewer than 50% of financial advisors

even deliver ‘The Plan’ (whether via financial planning software output or their own

custom-written plan) to clients now, as collaborative planning processes rise.

• In addition, the most productive advisors are ‘levelizing’ planning work across the

life of a client relationship, in place of investing increasingly inordinate amounts of

time upfront in the initial year. For the typical advisor managing $1 million or more

in revenue, first-year time spent on a client, at 24 hours, is just 4% greater than the

23 hours in annual time spent in ongoing years. The comparable difference for less

productive advisors is significantly greater, with a 45% drop from 29 hours in the first

year to 20 hours in subsequent years.

Mid-Size Service Teams With 3–4 People Are The Sweet Spot

• The structure of an advisor’s service team is more impactful than the choice of

technology when it comes to advisor productivity and presents further opportunities

for the advisor to better manage time and raise productivity. The optimal team,

including senior advisors themselves, has 3 or 4 members. In addition to being a

sufficient size to offer career paths, this is also the range where productivity peaks,

in terms of both revenue per advisor and revenue per all team members. Typically,

these mid-size teams will consist of a senior advisor assisted by an associate

advisor and a client service or administrative support role to handle back-office

responsibilities. As the client count grows, a service advisor is added and delegated

relationship management of the team’s least complex relationships.

• While they may help to leverage productivity and capacity, a larger team doesn’t

necessarily reduce an advisor’s working hours, however. Typical senior advisors in

5-person teams work 22% longer annual hours than senior advisors in 2-person

teams. The time that advisors in bigger teams save by delegating to support staff is

offset by the greater oversight burden of managing a larger service team, though

productivity does rise as the team can support a higher number of (often more

affluent) clients.

• The ability to delegate has positive benefits on productivity, and the impact of

shifting just a few hours of advisor time away from back- and middle-office tasks

toward more time in client meetings can be material. High-productivity advisors

(those managing $1 million or more in revenue) devote 39% of a typical work week

to front-office activities, including meeting with clients as well as prospecting and

marketing. In contrast, lower-productivity advisors spend just 29% of their time

Executive Summary | 8 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

conducting front-office work. Client meeting time accounts for virtually all the

difference, where the most productive advisors are spending an average of 4.4 hours

more per week relative to less productive advisors. However, it’s also notable that

even the most productive advisors still spend ‘just’ 39% of their time on front-office

activities, as advisors can still only manage and maintain a meaningful connection

with so many client relationships, even with technology and team support.

Capability To Serve Affluent Clients Eases

The Path To Higher Productivity

• A clear correlation exists between advisor productivity (as measured by revenue per

advisor) and client wealth. Wealthier clients have more complex and demanding

needs, and a greater willingness and ability to pay for the higher level of advice it

takes to solve for those needs. For advisors managing $1 million or more in revenue,

the investable assets of a typical client are nearly double that of less productive

advisors.

• Advisors, however, need the right capabilities to serve wealthier – and typically more

complex – clients. These capabilities come in the form of their own education, skills,

and experience, in addition to other expertise they may have access to.

• Regarding external resources, those advisors serving more upmarket clientele are

far likelier to rely on outsourced support, typically centralized financial planning

specialists that are within the firm but external to the service team. For example,

outsourced support is used by 55% of advisors serving clients with $3 million or more

in assets versus just 41% of advisors serving clients with $1 million or less.

• Relative to the expertise of others they may have access to, advisors’ capabilities

to serve a wealthier client are even more correlated with productivity. In terms of

revenue per advisor, the typical senior advisor with 10-plus years of client-facing

experience is more than twice as productive as a less-experienced senior advisor.

Education, in the form of specialized degrees and advanced certifications, also sets

an advisor apart in terms of greater productivity. Having only CFP certification, for

example, correlates with an additional $100,000 in revenue per advisor.

Capturing Opportunity By Taming Time With Moderation

• Advisors have only so many hours in a day to adequately implement the financial

planning process across increasingly demanding clientele. How these hours are

allocated, and with whom, has a significant bearing on an advisor’s productivity and

income-generating potential.

• Real productivity boosts start with earning more on the advisor’s time, which

typically means establishing the skills and capabilities for attracting and retaining

more affluent clients.

• Further, rather than going ‘all-in’ on expanding or enhancing a business function,

a more reserved approach is frequently more effective. Building out a service team

beyond 3 or 4 individuals, for example, appears to typically result in diminishing

returns. Similarly, compared to offering a custom-written plan, a collaborative

approach is less costly to deliver and likely a more satisfying experience for the client.

And while it may be unrealistic for an advisor to maintain focus when spending 70%

of a workday in client meetings, increasing meeting time to just 20% to 30% of the

workday would realize material productivity gains.

• The financial planning environment may be growing more demanding, but

business complexity also means greater opportunity – opportunity that is within

reach of any advisor that can better leverage time.

Executive Summary | 9 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

Introduction

Study Objectives And Coverage

In 1995, CFP Board (Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc.) first established

its set of Practice Standards. These standards helped to define the financial planning

process and set a minimum level of expected professional practice for any individual

engaging in financial planning. Recently revised in 2020, there are now 7 steps that

make up CFP Board’s financial planning process, around which it has Practice Standards

to define what a competent professional would do within each step of the process.

The advisory profession is to be commended for the progress it has made in developing

and advancing this financial planning framework. In many respects, however, defining a

process framework for financial planning may be the easy part. Exactly how a planner or

advisor should implement this 7-step process is a more difficult question to answer. To

date, individual practitioners are largely left to resolve the implementation challenges on

their own, given the limited available guidance on the topic.

Since 2018, Kitces Research has sought to rectify this situation by researching and

reporting on exactly how advisors do financial planning. More specifically, our primary

study objectives are as follows:

• Shed deeper insight into how advisors are ‘doing’ financial planning, with a special

focus on the 4 domains of time, process, tools, and pricing;

• Highlight the ‘best practices’ of the most successful advisors; and

• Identify trends in financial planning productivity over time.

This is the third report focusing on the financial planning process. Following the

inaugural 2018 report, an update was released in 2020. With each successive study,

Kitces Research has provided advisors with more and deeper detail on how financial

planning is getting done. This report is no exception – few, if any, research efforts

have ever produced this level of detail on how the financial planning process is being

executed in practice.

Coverage is primarily organized according to 4 domains:

Time. How financial planners spend

their time and how time is allocated

by role across the entire financial

planning service team.

Planning Process. Service team

characteristics, plan development, and

first-year and ongoing client servicing.

Planning Tools. Technology tools

usage and satisfaction ratings.

Advice Pricing. How advisors get paid

in terms of charging methods and

levels of fees.

Throughout, the overarching theme is “productivity” – particularly the effectiveness of

how the time advisors invest in the client translates into revenue generated for the advi-

sors’ services, knowledge work, and expertise. Given this focus, study participants were

restricted to only those individuals who have a direct role in financial planning within an

advisory practice or firm.

Introduction | 10 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

Survey Participants And Methodology

This report utilized data collected online from September 15th through October 15th of

2022 via the Kitces.com platform. Participation in the Kitces Research survey was pro-

moted through articles on the Nerd’s Eye View blog as well as via email and social media.

Over 1,600 responded to the roughly ⁄-hour, 86-question survey. Of these, 767 were

usable responses that met our stringent qualification and completeness criteria. To be

eligible for the study, respondents were required to represent a business that provided

financial advice or implemented investment products. In addition, the practice had to

have been located in the United States and established in 2020 or earlier (such that it

served clients and earned revenue in 2021).

Different from past Kitces Research studies, the focus of this current study is at the level

of the client service team, as opposed to individual advisors (though obviously, for solo

advisors, the individual advisor still is the team). We focused on teams in recognition that

these are the core units within the firm that are most accountable for the financial plan-

ning process. For the purposes of this research, a “service team” is defined as a group

of individuals or a single individual with a practice that serves a defined base of individ-

ual clients. (See Appendix - Study Terms for a more detailed definition of this and other

study terms.)

While the survey focused on all facets of the financial planning process, the questions

also covered the general demographics of respondents and the characteristics of their

service team. Participants represented their own individual work with clients either as

unsupported solo advisors or as part of a bigger client service team.

Given that the survey drew from Kitces.com readers, it is important to also recognize

that this group is somewhat unique as a sample of the broader financial advisor com-

munity. The readership is generally more advice-centric and planning-centric relative

to the broader industry that still has more of a product-sales tilt. This matters because

results by the very nature of those sampled may not be fully generalizable and represen-

tative of all those who call themselves ‘financial advisors’. Conversely, the results should

be especially meaningful to ‘financial advicers’ – those that are in the business of deliv-

ering financial advice (not products) to clients and getting paid for financial (planning)

advice itself.

Across respondents, the median age of the practice each was affiliated with was 12, with

years in business ranging from 1 to well over 20. In terms of service team size, the typical

respondent represented 3 full-time advisors and support team members (including the

lead advisor themselves). Teams handled a median of about $600,000 in revenue. Their

business channel was overwhelmingly RIA (58%) or Hybrid (26%), with most revenue

coming from AUM fees (73%). For most practices (68%), the typical client served was age

55 or older. Their client size was most often in the range of $750,000 to $1.5 million in

investable assets. Over half of the typical respondent’s clients (53%) were provided with a

new or updated financial plan during the past year. (See Figure 1 for further detail.)

Figure 1. Summarizing Survey Respondents

Ranges represent 25th to 75th percentiles unless noted otherwise

Introduction | 11 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

It’s About Time

What is the most overwhelming dominant challenge for advisors aiming to succeed

at financial planning? It’s that the process is time-consuming. More so than how to do

financial planning, the greater concern for the typical advisor is simply how to make

time for what it takes to deliver financial planning to each and every client. The prioriti-

zation is entirely rational.

Time is a finite resource. In a business that is heavily people-dependent, time is nearly

always the primary constraint on financial planning capacity. And efficiency gains can

only take an advisor so far; many critical planning functions simply can’t be automated.

You can’t automate away the time needed to meet with clients in order to build rela-

tionships. You can’t automate the intellectual capital of good advice. Similarly, you can’t

completely automate the ability to get clients to modify their behavior and win their

buy-in and support to implement a beneficial strategy.

Getting tighter control of time starts with a better understanding of how it is expended.

On average, a senior advisor works a manageable 41 hours in a work week, about 2 hours

less than the nearly 43-hour average for full-time U.S. workers of any type

1

.

Figure 2. Hours Worked By Role

1

https://www.bls.gov/charts/american-time-use/emp-by-ftpt-job-edu-h.htm

Relative to other common advisory firm roles, service advisors work slightly less, aver-

aging 40 hours (Figure 2). Executives and financial planning specialists work a bit more,

averaging 43 hours. At 44 hours per week, workloads are highest for associate advisors

(the remaining role for which we have sufficient reporting data). All 5 of these roles typi-

cally take 4 weeks off per year (combined vacation and sick leave).

The 41.4 hours averaged per week across all respondents is down notably relative to our

past financial planning studies. In 2018 and 2020, weekly hours averaged 43.0 and 43.7,

respectively.

Covid is likely driving the recent decline, given that our 2020 study, representing the

peak for weekly hours, was fielded in the Spring of that year. At that time, the pandemic

was just taking hold, and advisors were anxiously working overtime to field calls from

worried clients while also re-crafting operating procedures to limit face-to-face inter-

actions and reduce the risks of infection. Now, 2 years later, this pandemic-induced

transformation appears to have resulted in lasting efficiency gains. Video meetings and

online collaboration between advisors and clients, for example, are now commonplace

and clearly reducing demands on an advisor’s time. We’ll explore this phenomenon in

more detail further ahead in this report. In addition, Covid may have prompted a ‘reset’

in terms of attitudes toward the importance of work/life balance, with workers not plac-

ing as high a priority on longer workweeks.

Bigger Teams Lead To Busier Advisors

While the average advisor may be working a shorter week, longer hours are charac-

teristic of certain advisor groups. One surprising example is a clear positive correlation

between the senior advisor’s number of hours worked and the size of the service team

they work with. Figure 3 displays the median weekly hours worked throughout the most

recent year, adjusting for weeks worked during the year. Counter to popular belief that

hiring and delegating will allow advisors to save time, a bigger team doesn’t always

synch with an advisor working any less. (Further, there is not a clear linear relationship

between team size and advisor productivity, as we will discuss more fully in our section

on service teams.)

It’s About Time | 12 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

Figure 3. Senior Advisor Hours Worked By Size Of Service Team

In other words, while there are real advantages related to larger service teams, lower

hours for senior advisors are not one of them. As shown, senior advisors working with

5-person teams are logging 22% more hours annually than those within a 2-person

team. (We’ve avoided comparing to 1-person teams given that many of these are unsup-

ported solos who work less than full-time, either by preference or simply because they

haven’t reached a ‘full’ client base yet.) A similar trend is evident when team structures

become complex. Senior advisors within ensemble firms work 13% more hours annually

than those working as supported solos (likely at least partially attributable to the extra

hours that have to be invested into management and leadership, and employee com-

munications within a larger team).

The tendency for bigger and more structured teams to work with larger (and thereby

usually more demanding) clients also likely contributes to a greater senior advisor work-

load. But even more so, it appears to be the management burden on senior advisors as

they move to manage more people and more complex teams. This suggests that hiring

more support doesn’t necessarily represent the path for advisors to lighten their work-

loads, as the time saved from delegation is more-than-offset by the additional time to

manage those delegees.

Commission Business Requires Greater Time Investment

Advisor hours also vary widely according to their channel and, relatedly, the advisor’s

majority source of revenue. As Figure 4 shows (again, adjusted for time off), senior advi-

sors in broker-dominated channels work significantly more hours than advisors affiliated

with an RIA. A typical IBD advisor without an RIA, for example, works 20% more hours

than a senior advisor in a ‘pure’ RIA—a difference of nearly 8 hours per week!

Figure 4. Senior Advisor Hours Worked By Channel

This occurs despite the broker-dealer affiliated advisor’s access to home office support

resources. Which means even if a resource advantage exists for the broker-dealer-affil-

iated advisor, it is more than offset by the greater time commitment associated with a

commission-based business. This may include a greater need to continuously find new

clients, as well as increased compliance obligations of working within such a firm. In

turn, our results also show that senior advisors who are mainly dependent on commis-

sions work 20% more hours than those that primarily rely on AUM fees. The difference,

identical to that between RIA and IBD advisors, implies that the more transactional

nature of commission-based business requires a greater time commitment relative to

RIA advisors, who oversee practices that are largely relationship and fee-based.

It’s About Time | 13 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

Advisor Hours And Revenue

Do longer hours pay off in terms of productivity? A loose correlation does exist – on an

annual basis, an additional 100 hours worked separates advisors generating $1 million or

more in client revenue from advisors under $1 million. Further parsing our data, however,

shows that the link between hours worked and revenue generation is hardly a smooth

upward trajectory (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Senior Advisor Hours Worked By Revenue Per Advisor

Typical hours worked seesaws as senior advisors increase their productivity, but overall,

advisors generating $1M+ of revenue are working nearly identical hours to those who

generate ‘just’ $250–$400k of revenue. As the saying goes, the key to success is to “work

smarter, not harder”, and this is reflected in our results. As discussed further ahead, the

key for advisors to lift their productivity is not working more hours to take on more cli-

ents; it’s to increase their expertise and the complexity of the problems they solve, which

allows them to work with more affluent clients who pay higher fees to solve those more

complex problems, enabling the advisor to generate more revenue from the hours they

spend advising clients.

Notably, the relative stability of hours worked by revenue also suggests that the classic

desire of advisors to “just grow a little larger, to be able to hire another staff member to

free up time” remains unfounded. As noted earlier, on average, advisors who expand

their teams tend to spend more time in their businesses, not less. And given that the

overall average hours worked is relatively stable as revenue rises, this implies that for

every advisor who adds headcount as their revenue grows (increasing their time), there

is another advisor who doesn’t add headcount and manages to reduce their time spent

at higher revenue (again, by working with fewer, more affluent clients, who are willing to

pay the advisor substantively more for the value of their time to generate greater reve-

nue in fewer hours worked).

Where Does Time Go?

What exactly individual advisors do

with the time they commit to their

roles offers a deeper perspective

on time management. Our survey

respondents, in addition to report-

ing on the practices of their teams

at large, also provided very specific

detail on their roles as individuals

within the team. This included inven-

torying their weekly time on the job,

bucketed according to 13 different

activity groups (summarized on the

right).

For the 5 different advisory firm roles

where sufficient data were available,

Figure 6 summarizes the allocation

of respondents’ time grouped at

a high level according to whether

time was spent on a back, middle,

or front-office function. Figure 7,

which follows, offers a more detailed

accounting by specific activity.

It’s About Time | 14 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

Figure 6. Time Allocation By Front, Middle, And Back Office

At a high level, there is only modest differentiation across roles. The minimum share

any role devotes to front office work is 20%. Of all roles, the senior advisor spends the

most time on client-facing front-office activities, as should be expected. The bulk of this

front-office time, about 60%, is devoted to client meetings, with prospecting and other

marketing activities making up the remainder.

More surprising, however, is that as critical as the senior advisor is to the success of client

relationships, only 30% of their time is focused in that direction (and just 17% of the advi-

sor’s time is in meetings with clients, with the rest spent on marketing)! Which means

that during a typical workweek, actual client meetings take 7 hours. This is likely 1–2

hourly client meetings per day (or, more commonly, 3 days per week with 2–3 meetings

per day, with time for meeting preparation and follow-up set for Mondays and Fridays).

Which, on the one hand, implies a tremendous opportunity for firms to better leverage

their senior advisors so that they can become more truly client-focused. However, as

discussed later, this may also be a signal that advisors can only manage ‘so many’ client

relationships requiring high-focus client meetings in the first place, as advisors with

larger teams and more support still don’t exhibit significantly higher amounts of time

allocated to client meetings!

Figure 7. Time Allocation By Specific Activity

It’s About Time | 15 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

As their more support-oriented roles would imply, service advisors and associate advisors

allocate the most time to back-office functions, each at 27%. The bulk of their time in this

area goes to client servicing tasks. Advisory firms may be under-utilizing administrative

support for their service advisors, however, given that service advisors are in ‘lead’ posi-

tions of managing client relationships.

Middle-office activities are clearly the domain of executives, financial planning special-

ists, and, to a lesser extent, associate advisors. All 3 roles spend more than half of their

time on middle-office functions. Unsurprisingly for executives, general management

accounts for the most time they spend in this area. While for the others, middle-office

time is most impacted by the time spent on financial planning analysis and related

knowledge work for clients (as would be expected), with nearly half of middle-office

time (and about ⁄ of all time) for financial planning specialists going directly to financial

planning preparation. To a lesser extent, planning prep is also the most prominent mid-

dle office activity for associate advisors. Except for less time on planning and more time

servicing clients, the average associate advisor’s distribution of time closely resembles

that of the financial planning specialist.

Optimizing The Senior Advisor Role

What potential exists for senior advisors to better allocate their time, take the best

advantage of the roles that support them, and raise their productivity? While the alloca-

tion of time varies little by the experience level of the advisor, there are notable shifts as

advisors grow more productive. Reviewing these differences offers some key lessons.

Figure 8 compares the distribution of time spent on front, middle, and back-office

functions as senior advisors increase their productivity in terms of the revenue they are

responsible for. For the most productive advisors, those generating $1 million or more in

revenue, front-office time is 39% of their typical work week versus just 29% for advisors

generating less than $1 million in revenue. The $1 million-plus advisor, relative to others,

devotes less time to both middle and back-office activities to focus more time directly

on clients. Their reduction in back-office work is especially significant.

Figure 8. Senior Advisor Time Allocation By Revenue Per Advisor (Front, Middle,

And Back Office)

It’s About Time | 16 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

Figure 9 details the specific shifts in emphasis that take place when an advisor crosses

the $1 million divide. Most notable is the increase in client meeting time (also accom-

panied by a slight increase in meeting prep time). While on the one hand, shifting

another 10% of a workweek toward more client-facing time may not seem significant –

it amounts to a little more than 4 hours per week, with less-productive advisors aver-

aging 6.4 hours of weekly client meetings versus 10.8 hours for the most productive

advisors (there is no meaningful difference related to business development between

the 2 groups) – over the span of a year, an extra 10% time allocation permits the most

productive advisors to add nearly 200 1-hour client meetings per year, allowing for a sub-

stantively deeper level of client relationships by sheer virtue of increased meeting and

contact frequency.

Regarding what the $1M-plus advisor does less of in order to free up time for clients,

reductions are evident across all middle and back-office activities, except for a slight

increase for general management (likely a result of having more of a support team to

delegate to in order to free up their time, but this requires at least some management

load to oversee them). The largest reduction occurs in financial planning preparations,

driven by support from associate advisors or centralized (or outsourced) financial plan-

ning specialists. The most notable reductions in back-office activity are for client servic-

ing and administrative tasks, as administrative staff support is also expanded for such

advisors. Though notably, most time allocations in these areas shift by no more than 1

or 2 percentage points of the senior advisor’s time, amounting to only 30–60 minutes of

time savings in each area in any particular week.

In sum, focusing on face time with clients is clearly a path to greater productivity, but it

is far more a ‘game of inches’ than one of radical change. The most productive advisors

are doing this largely through saving ½ –1 hour per week on financial planning prepara-

tions as well as time on client servicing and administrative tasks (whether automated or,

more likely, via delegation to other roles, in particular, an associate advisor, paraplanner,

or financial planning specialist). In turn, these few hours of savings can then be reallo-

cated to pick up ‘just’ another 2–4 client meetings each week.

Lastly, it’s also notable that even the most productive advisors look to have further

potential to limit time spent on less essential middle and especially back-office functions

(where even the most productive advisors still spend 17% of their time or about 6–7 hours

per week on back-office tasks), yielding even more time for clients and ultimately being

able to achieve even higher rates of revenue productivity.

Figure 9. Senior Advisor Time Allocation By Revenue Per Advisor (Specific Activities)

It’s About Time | 17 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

The Planning Service Team

Team Size And Composition

Kitces Research defines “service team” as 1 or more individuals, working within a financial

advisory firm, that are collectively serving and delivering financial planning advice to a

defined client base. Shared resources, such as centralized financial planning specialists,

an investment/trading team, operations staff, or outsourced support external to the prac-

tice, were not considered as part of the service team for the purposes of the research.

At a minimum, service teams will have at least 1 individual managing client relationships

and leading the delivery of financial planning advice. Most often, this is a senior advi-

sor who is accountable for client relationships, business development, and mentoring

others. Occasionally, in the absence of a senior advisor, a service advisor (accountable

for managing and retaining existing clients but typically with little or no new business

development responsibilities) will lead the team. Support roles within the team may

include an associate advisor, paraplanner, or client service administrator (CSA).

By this definition, the median size of financial planning teams participating in this sur-

vey was 3 – most often consisting of a senior advisor (who may be an owner/founder), a

second service or associate advisor, and a client service administrative employee. Only

about of respondents reported a team size greater than 3 (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Service Team FTE Range

The typical 3-member team is not coincidental; our results show a 3, or possibly 4-per-

son team is most often optimal. At this size range, the team is small enough to limit the

challenges and burdens of people management but also big enough to provide some

redundancy for limiting service gaps and leveraging the lead advisor’s time. In addition,

there is sufficient size for a simple career path to better facilitate employee development.

Larger teams tend to serve more affluent clients and generate more revenue per client,

likely due to broader capabilities. The mid-size team, however, is a sweet spot in terms

of productivity. This is true in terms of both the most revenue generated and the most

clients served per advisor across the entire range of team sizes. As shown in Figure 11, the

typical revenue per advisor in a 3-member team, at $610,000, is 57% greater than advi-

sors in 2-person teams and 44% greater relative to 5-person teams.

Figure 11. Revenue Per Advisor By Team Size

The Planning Service Team | 18 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

The typical 4-person team does nearly as well in terms of revenue per advisor while

achieving the highest productivity in terms of revenue per team member (revenue

across the service team divided by the total number of team members, including

advisors). At $278,00 in median revenue per team member, 4-person teams are $3,000

higher in productivity by this measure than their 3-person counterparts (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Revenue Per Team Member By Team Size

Even more impactful than the number of individuals on the team, however, may be the

roles that constitute a team and how roles evolve as the team grows. The most common

role, after the senior advisor, is the CSA – 60% of teams employed at least 1 (Figure 13).

Less than of teams employed a service advisor, associate advisor, or paraplanner.

Figure 13. Frequency Of Roles Used

Using this data, it is safe to assume that most 1-person teams are simply a sole senior

advisor, with the hiring of a CSA typically marking the progression to a 2-FTE team. Fig-

ure 14, displaying the prevalence of each role by the size of the service team, confirms

that the CSA is the second-most common position in a 2-person team, following the

senior advisor.

Figure 14. Roles Teams Use By Team Size

From Figure 14, in combination with analysis of the actual team rosters of respondents, a

more complete continuum emerges. Below, Figure 15 summarizes a typical progression

in terms of team composition by roles as a team increases its members. As shown, with

3 members, a team most often consists of a senior advisor, an associate advisor, and CSA.

4-member teams are often distinguished by the addition of a second advisor account-

able for client relationships – this comes in the form of a service advisor, who may either

be hired anew or promoted from the associate advisor (who becomes a service advisor

and is then back-filled with a new associate advisor). The addition of a second senior

advisor (i.e., a second person responsible for business development) typically rounds out

the 5-person team, either by addition or the promotion of a more growth-oriented ser-

vice advisor. A typical 6-person team might have a similar make-up but with 1 additional

CSA to support what is now typically a 4-advisor team.

The Planning Service Team | 19 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

Figure 15. Typical Service Team Structure By Team Size

Median Team Size: 3

Note that while our illustration represents what is typical, there are many variations to

this theme.

Paraplanners, for instance, were utilized overall by 23% of teams, but the role was left

out of our progression summary. As it turns out, paraplanners are not actually a com-

mon hire for any team size! Amongst 2–3 person teams, as noted above, advisors are far

more likely to hire an associate advisor to work alongside them in client meetings than a

paraplanner to provide behind-the-scenes financial planning support. Consequently, to

the extent that they are present, paraplanners are typically only employed by the largest

teams. This is because paraplanners appear in practice to be primarily used to leverage

multiple advisors at once, which typically means after a team has at least 2 advisors in

place and, more commonly, after 3 or more (usually a combination of senior, lead, associ-

ate, and service). However, even among the largest teams (5 or 6 members), fewer than

half have a paraplanner, and their frequency appears to drop as teams reach 6+ team

members… in all likelihood, because as firms reach this size, they don’t include paraplan-

ners directly on teams at all, and instead utilize them as part of a centralized financial

planning support unit that assists multiple service teams of advisors.

Of course, teams don’t need to grow by whole numbers, either. Of all surveyed teams

ranging from more than 1 FTE up to 2 FTEs, were less than 2 FTEs. In other words,

many solos preferred to build up gradually by making a part-time hire first rather than a

full-time hire. In virtually every instance, this was a part-time CSA that the firm was using

(either on a sustaining basis or until it was ready for a full-time CSA hire).

External Resources

External staff resources, either from elsewhere within the advisory firm or outside of it,

often supplement a direct service team. Across survey respondents, while 57% reported

their teams had no access to external planning support, ⁄ of teams tapped into out-

sourced support, and about 1 in 6 teams made use of centralized planning or technical

specialists within their own firms (Figure 16). (Note: teams may have reported using

more than 1 form of external resource support.)

Figure 16. Reliance On External Support To The Team

Surprisingly, teams that rely on outside support tend to be larger than teams without it.

2 FTEs make up the typical team that does not access outside support, compared to 3

team members for those that do. Despite bigger teams, no particular role seems more

prevalent with teams that tap into outsourced support. As Figure 17 shows, every team

role tends to be more prevalent.

The Planning Service Team | 20 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

Figure 17. Reliance On External Support By Frequency Of Roles Used

Why do bigger teams access outside help more than smaller teams? Why do teams out-

source at all? The advisor’s distribution channel provides a partial answer to these ques-

tions. Further explanation is that bigger teams and extra resources are often required to

fulfill the growth strategy of the practice.

Figure 18 summarizes key outsourcing differences by channel. The less independent

their channel, the more likely advisors are to get support from outside their own teams.

For example, just 37% of RIA teams access outside support, compared to 70% of W2 Bro-

ker teams. RIA’s, in particular, tend to lack the in-house financial planning and technical

resources that are often more readily available within the brokerage channels. In both

the IBD and W2 Broker channels, less than half who use outside support access support

that is outside their own firm (instead of from somewhere else within the advisory firm).

By contrast, at least 50% of RIA and Hybrid teams rely on outside support from beyond

their own firms.

Figure 18. Reliance On External Support By Channel And Support Type

Growth and business strategy, in terms of the kind of client a team targets, also influ-

ence outsourcing and service team resources. Teams that serve bigger (i.e., more afflu-

ent and typically more complex) clients not only tend to be bigger in terms of FTEs, but

they are also more likely to access expertise outside of the internal team. While 55% of

the teams whose typical client is $3M or more access outsourced support, this share

declines to only 41% for teams whose typical client is $1M or less.

Teams focused on a niche market, although similar in size to those without a niche, are

also more apt to use outside support. In teams where or more of their clients fit a niche

profile, about half (51%) of teams outsourced, compared to just 40% for other teams. Out-

sourcing also correlates positively with the breadth of financial plans provided.

In essence, then, the leveraging of external support resources for financial planning

appears to be less a matter of delegating tasks and services (e.g., a department to do

the labor-intensive work of building financial plans) and more a matter of being able to

The Planning Service Team | 21 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

tap specialized knowledge resources outside of the typical generalist expertise that is

available within a team. For instance, niche advisors may leverage external support for

financial planning expertise that is unique to their niche, and advisors who work with

the most affluent clients may leverage external support specific to addressing the spe-

cialized problems of HNW clientele.

While outsourcing may be a requirement for more specialized or comprehensive

approaches to advice, it also looks to be warranted in terms of greater reward. The more

productive the advisor, the greater the likelihood that they are associated with a service

team that accesses outsourced support. By tapping more robust expertise through

outsourcing, a team is better equipped to handle more affluent clients, who tend to pay

higher fees to access solutions to more complex problems. As a result, revenue gener-

ated per advisor is $420,000 when a team outsources, 20% greater than the $350,000

median for those advisors who do not seek outside help.

Team Time Per Client

Whatever the composition of a service team, optimally it will be positioned to best meet

the needs of targeted clients. This includes devoting sufficient time to adequately serve

these clients. Including establishing the relationship, setting up accounts, and initial

planning work, the first year of the new client relationship is the most time-consuming.

Across all service team members, the median time devoted per client is 29 hours in the

first year of the relationship. Time per client drops significantly, 38%, to 21 hours per year,

in the subsequent ongoing years of the relationship.

Time committed to clients will vary, however, according to the unique characteristics

of the advisor’s business model. One clear example relates to the distribution channel

of the advisor, which is often correlated with how clients are charged, the nature of the

client relationship, and the wealth of the client. As shown in Figure 19, RIA advisors spend

the greatest amount of time with clients, both during the initial year and ongoing. Com-

pared to a commission-based IBD broker, the RIA advisor spends 60% more first-year

time and 35% more on an ongoing basis.

The differences in time are a likely result of serving different types of clients in differ-

ent ways. The RIA advisor typically charges for providing expert advice exclusively via

an ongoing AUM fee and, as a result, tends to form long-term relationships in order to

retain that recurring revenue. The IBD broker, relying only on commissions, often has

more transactional relationships, as once the purchase is made, the broker is not com-

pensated for the ongoing relationship (until/unless there’s an additional transaction).

Figure 19. Total Team Time Per Client By Business Channel

Time devoted to clients also tends to increase when serving larger portfolio clients,

similar to the relationship between team size and client wealth. As Figure 20 illustrates,

larger clients tend to get more of a team’s time, most notably in the first year. (The data

also shows that RIAs tend to serve more affluent clients than brokers, which likely further

contributes to the higher time-per-client that RIAs provide relative to brokers.)

Figure 20. Total Team Time Per Client By Client Size

The Planning Service Team | 22 of 67

The Kitces Report, Volume 1, 2023

More than double the time is spent in Year One on a $10M+ client versus a client

between $250,000 to $750,000 in investable assets. This compares to an increase of just

44% in ongoing years. The greater first-year disparity likely reflects more time to com-

pete for and cement these more sought-after relationships. Further, the larger client is

typical more complex, with planning needs that require more analysis and deeper rec-

ommendations and implementation.

Surprisingly, though, the most productive advisors have managed to ‘flip the script’

regarding how time is apportioned across Year One and ongoing clients. For teams with

lead advisors generating $1M or more in client revenue, little difference exists between

time spent in Year One versus the following years of a client relationship (Figure 21). Rela-

tive to teams with less productive advisors, they are typically spending 5 hours less per

client in the initial year but 3 hours more on an ongoing basis. These results suggest that

economizing time in the first year of a client relationship is a critical contributor toward

greater overall productivity and, more generally, that advisors may be ‘over-servicing’

clients in the first year of the relationship relative to what the most productive advisors

have been able to implement in a more levelized-service manner.

Figure 21. Total Team Time Per Client By Revenue Per Advisor

A Process Of Compromises

In summary, team structure has very real implications for the kind of clients the team

can attract and productively retain. Developing the right planning service team can be

a challenging process of compromises. This includes compromises of time, allocating

work to be done, addressing client needs, and managing advisor capacity (including,

ironically, the capacity of the advisor to manage more people in addition to their own

client capacity!) – all of which are pushing and pulling at different times and at different

strengths. What type of client the team intends to serve, and how, can provide invalu-

able guidance for managing these compromises.

All that said, our data provides actionable advice for any advisor looking to structure an

optimal team. The following considerations are important to bear in mind, regardless of

an advisor’s specific business objectives: