Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

Net Present Value Tool Description

This document explains how to use the Net Present Value Tool. Net Present Value (NPV) is a

financial calculation that determines the risk-adjusted value (called the discounted value) of a

series of cash flows over time. It is a way of determining, in currency, if a New Product

Development (NPD) project can be anticipated to be worth the cost given the risks involved and

make money for the company or organization developing it.

At the core of NPV is the awareness that a dollar tomorrow is not worth the same as a dollar

today if you are not sure you are going to get it. The dollar tomorrow is worth less. Therefore, it

must be discounted when compared to today’s dollar, to reflect that risk. Inflation can cause the

same phenomena of reducing value so it may be added to the discount rate for an NPV

calculation if it is significant. In the NPD process, NPV is used to determine whether the NPD

project is on track to meet its financial targets. NPV can also be used to assess the potential

value of different NPD initiatives as part of portfolio creation and evaluation.

The NPV Tool provides a worksheet to enter estimated cash flows and discount rates for an

NPD project. Embedded formulas in the tool will then generate estimates of future cash flows for

each stage of the NPD project from the Idea stage through Launch, and then into the Post-

launch stage. The tool will provide the calculated NPV at selected intervals over a specified time

period stretching into the future. This tool can be modified as necessary to incorporate factors

that are specific to the NPD project. In addition, the tool can be run repeatedly with different

inputs using different assumptions for each run, to generate multiple cash flow and NPV

scenarios that can then be compared to test the possible outcomes of different decisions.

What is Net Present Value?

Net Present Value (NPV) is equal to the sum of discounted future net cash flows minus any

investment. This document provides a brief introduction to calculating NPV. For those desiring

more information, a review of the Damodaran OnLine website hosted at New York University

1

is

highly recommended, where you will find tutorials on all aspects of valuation as well as a wealth

of data and sources for data to use when making calculations.

NPV is the difference of today’s value of a set of future cash flows minus today’s value of the

cash that must be invested to realize those cash flows. The cash flows used in NPV calculations

come from subtracting revenues from expenses. The discounting used in NPV reflects the

likelihood that those cash flows will not materialize. The discount rate in an NPV calculation is

simply the risk that the cash flow might not materialize.

1

Damodaran Online, available at https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/)

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

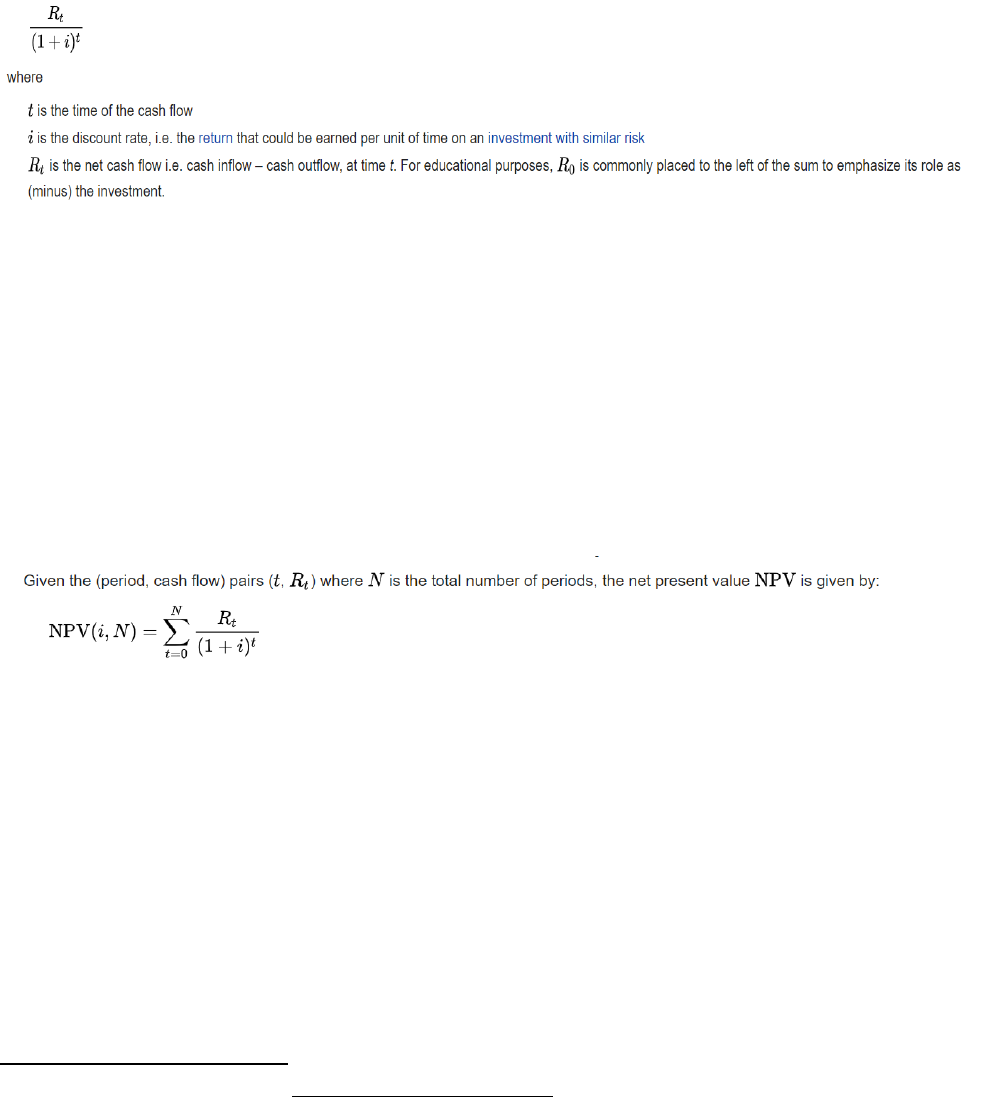

The first part of the formula for NPV of a specific period is the net cash flow for that period,

divided by 1 + the discount rate raised to a power equal to number of periods until the period is

reached for which the net cash flow has been calculated. Each time period must be of the same

duration. Mathematically the formula for a single future cash flow period looks like this:

2

Figure 1: Discounted net cash flow formula for a specific period

The second part of the formula addresses R

0

the current period cash flow. If period 0 has

ended, by definition the investment for the current period is known with certainty and does not

need to be discounted. It is simply subtracted. Similarly, if revenue was booked in the current

period, it also is known with certainty. An example of revenue in an NPD project might be

receipt of a government grant payment supporting your new product research and development

(R&D). Regardless of whether it is negative or positive, the net cash flow for the current period

is added to the sum of the discounted net cash flows.

Because NPV calculation relates to a series of cash flows, the discounted cash flows are

summed.

3

Figure 2: The formula for summing the discounted net cash flows

After summing, subtract the net initial investment (negative cash flow) or revenues (positive

cash flow) in the just-ended current cash flow period.

While the math used to calculate NPV is straightforward, the process for determining the

assumptions to use when estimating cash flows and discount rates is not. The next section of

this document discusses how to make these assumptions.

The discount rate can be calculated in a variety of ways. For many investments, such as a

capital expenditure to build a factory, the firm's weighted average cost of capital (after tax) can

be used. The weighted average cost of capital reflects the cost of capital (the interest rate paid

on a loan) on loans for different kinds of things, such as construction, equipment, operating

2

“Net present value”, Wikipedia, Net present value - Wikipedia, Accessed October 28, 2021. Used in

accordance with the Wikipedia license.

3

Ibid.

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

capital, and so on. The weighting reflects the proportion of the total sum to be borrowed for that

kind of loan.

However, few projects that involve investments today in the hopes of future revenues are

without other risks or discounting factors attached to them. NPD is an example. That is why the

discount rate is typically calculated from the ground up to account for risk when doing an NPV

calculation for an NPD project. Another reason to do a ground-up calculation of the discount

rate is to consider opportunity cost, inflation, or other factors.

In NPV, risk is systematically evaluated as best as possible – which is a polite way of saying a

guestimate is made – or a rule of thumb is used. Two rules of thumb are common. The first is to

use the discount rate which would be applied to an alternative venture, such as investing the

money in blue chip stocks or buying a government or corporate bond. The problem with this rule

of thumb is that NPD is usually riskier, so using this discount rate as a substitute might be

unrealistic due to the higher risk levels for NPD. Another rule of thumb is to use the firm's

reinvestment rate. The reinvestment rate is the average rate of return for the firm's investments

in other NPD programs in the past, or return on very similar NPD projects. This approach

reflects opportunity cost of investment in NPV, rather than the likely lower cost of capital of the

alternative investments. But as was mentioned before, this rule of thumb suffers from the fact

this is a generalized risk rate and not one specific for this NPD initiative.

Ground-up estimates of the discount rate must include four factors. The first is general macro

level risk that applies to any NPV calculation: anticipated inflation. The last three factors are

intrinsic to the specific NPD initiative. In The Wide Lens

4

, Ron Adner describes three main types

of risk that apply to NPD. Execution risk refers to the ability of your company or organization to

actually conduct NPD. Adoption risk refers to whether the intended customer segments will

actually buy the product or service being developed and the intended end-users actually deploy

it. Co-innovation risk refers to the ability of vendors, suppliers, and partners to provide what you

need as part of your NPD and to conduct their own NPD if that is necessary to develop

consumables or other essential goods needed to effectively deploy your product or service.

These risks need to be calculated and combined. The Gate Progress Review Tool can be used

to support making a ground-up determination of risks that will be used to estimate the discount

rate.

Recall the discount rate is simply the likelihood the anticipated cash flows will not materialize. In

other words, the discount rate is a probability. When adding probabilities, the critical question is

whether they are mutually exclusive or not. If they are mutually exclusive, you can simply add

them. If Adner’s three kinds of risk for the NPD project are mutually exclusive, the discount rate

is 1 minus the sum of the probability of execution risk plus the probability of co-innovation risk

plus the probability of adoption risk. This is expressed mathematically as follows, where D is the

discount rate:

D = 1 - (P

e

+ P

ci

+ P

a

+ I)

P is the probability of occurring and the subscripts represent the first letters of the kind of risk

(P

e

= execution risk probability, P

ci

= co-innovation risk probability, P

a

= adoption risk

probability), and I is the inflation rate.

4

Adner R., The Wide Lens: What Successful Innovators See That Others Miss, Portfolio; Revised edition

(June 25, 2013).

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

Almost always, Adner’s three risks are interconnected. Therefore, use the formula for summing

the probability of non-mutually exclusive events to calculate the project-specific rate and then

add in inflation as a mutually exclusive probability if you want to include it. The formula for using

the interconnected project specific risks is as follows, where P

NPD

is the probability of NPD

specific risk:

P

NPD

= (P

e

+ P

ci

+ P

a

) – P(P

e

and P

ci

and P

a

)

Next, add the interest rate to calculate the overall Discount Rate:

D = 1 – (P

NPD

+ I)

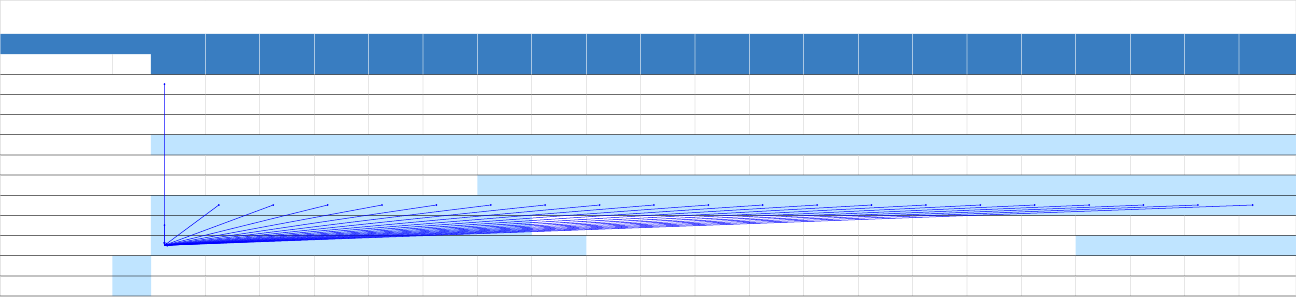

Because of its utility for doing a check on value for the developing entity, the NPV Tool can and

should be used as part of every gate review in a stage-gate NPD project, as indicated by the

green arrows in the graphic in Figure 3. A calculation of NPV can also be done to measure

value for customers and end-users if desired. In that case you would focus on their relevant

cash flows and risks.

Figure 3: NPV calculations are done at each gate review of an NPD project. At the early gates the NPD is just a quick

estimate. They get more refined as more data is collected as the NPD process progresses. It is especially critical at

the gate between the Design and Development stages due to the rapid rise of expenses that begins there, on the one

hand, and on the other hand, reasonable quality market data should exist for making a projection at this time.

The tool supports all the activities in Module III “Integrating public domain knowledge into

product development processes” of the WIPO publication Using Inventions in the Public

Domain: A Guide for Inventors and Entrepreneurs (2020). In NPD projects using a stage-gate

system, a calculation of NPV is made at every gate as part of the decision to move forward into

the next stage. Over time, the NPV of an NPD project should increase as each stage reduces

the risk of success. If it does not, there is a problem.

How do you enter data in the Net Present Value Tool?

To enter data, you first must estimate cash flows and discount rates.

Cash flow is simply money in and money out (i.e. revenues and expenses) for some specified

period. Cash flow is the lifeblood of a business or any other entity. It represents the money you

have control over to do with as you wish. Negative cash flow means you need financing to

operate. Sufficient positive cash flow means you can self-fund your operations. If cash flow is

v

V

V

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

high enough, you can even support growth. Thus, one of the key goals of NPD is to generate

free cash flow or positive gross revenues.

Discount rates are the risk that a cash flow estimated to be realized at a specified time in the

future will be worth less than the equivalent cash flow today. The discount rate used for NPD

NPV is like the interest rate used for a bank loan. Both capture an estimate of the reduction of

value of currency over a specified period due to risk.

It is critical to be clear about what you are doing in your calculations of cash flows and choice of

discount rates, so viewers of your NPD financial projections understand how the inputs were

created. You can exclude whatever you want from your calculations as long as you are open

and upfront about doing so. Similarly, for each assumption made, you should document it and

explain why it was done. The NPV Tool workbook provides a tab entitled “Assumptions and

notes” where you can enter assumptions, data used for calculations, data sources, etc., that

were used for the calculations carried out on the main “NPV – single rate” tab in the tool.

Aswath Damodaran, a famous professor of valuation at New York University, once said much of

the tedium in valuation is having to calculate cash flows. This is because calculating future cash

flows is a matter of making and justifying assumptions about revenues and expenses.

There are five steps for estimating cash flow:

1) Estimate the revenues. Revenues can be calculated in two ways. Either you calculate

the units that can be sold and multiply that by the price at which they will be sold, or you

calculate a market size in dollars and estimate what share (percent) of the market you

will capture. These revenues are called gross revenues or gross income, where gross

means before any other costs have been subtracted. Gross revenues are generated

from direct sales of products or services, grants, royalty payments if your company or

organization licenses technology, or dividends and profit sharing if the entity has equity

in another company. Since you are projecting cash flow, a separate calculation must be

made for each year.

For example, suppose you are estimating revenues from sales of a new municipal street

trash bin for cities. You might also look to see if someone has already collected that

data. Most likely, however, you will not find that it is already collected. You might try

counting the number of trash bins in every city of the country where you will sell it. That

would be a very burdensome activity in order to make an estimate. What you could do,

therefore, is get an idea of how many cities of various sizes are in the country. You could

call the city officials responsible for placing and maintaining public street trash bins in

cities of a specific size range and ask them how many are in their city. Then you could

take an average and multiple that by the total number of cities in the appropriate size

group. After doing this for each size group, you could add them up and have a market

size.

When calling those officials, you might also have asked them how often they replace

bins, how they select the ones to buy, and what they pay for trash bins. Let us assume

you have a clear competitive advantage so there is a reasonable basis to assume they

would definitely buy yours when it is available. Then by using the annual replacement

rate you can use the purchase price provided to calculate potential sales per year and

thus annual revenues. If there is not a clear competitive advantage and you do not have

confidence you can capture the total addressable market, you could determine how

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

many vendors there are, what their market shares are, and make an estimate of what

percent of the total addressable market you can capture each year. A similar approach

might be used if city officials are reluctant to bring in a new vendor even if their product

is clearly superior. Then you need to estimate the ramp-up of sales.

2) The second step is to calculate costs. Costs have two major components: costs of goods

sold (COGS) and operating expenses (OE).

For our purposes here, COGS are the anticipated direct costs associated with producing

and selling the specific product or service being developed, including materials, labor

and factory overhead. COGS includes the costs of the primary activities in Porter’s Value

Chain.

OE are other, more general business expenses such as R&D, general marketing,

administrative costs, etc. which support divergent product lines and families. The nature

of these expenses makes it difficult to allocate them to a specific product line or family

and thus include them in COGS. Instead, a percentage of COGS is commonly used. OE

are the support activities in Porter’s Value Chain. Sometime OE are excluded when

calculating the NPV of an NPD initiative to simplify things. However, when OE are

excluded it is important to make it clear to everyone that these costs are not included in

the calculation, or it would be misleading. Do not fail to include OE if the NPV will be

shown to investors.

Probably the best way to determine costs is to make a ground-up estimate of them. In a

going concern, if the product or service is similar to one already developed and now

being made and sold, an internal estimate will work. If your entity has not done anything

like this before, and if your product or service is like others on the market that are sold by

other companies, then you can look at the annual report of one of those companies or in

some government filing to see if they have included an income statement. From

examining such income statements, you can make an estimate of both COGS and OE

as needed, based on either a percentage of revenues or actual expenditures. A third

way to get cost data is to consult with experts and ask them for their best estimates.

3) The third step is to subtract costs from revenues. This calculation is done in two steps.

First, take gross revenues and subtract COGS to calculate gross profit, which is

sometimes called sales profit. The ratio of net income over gross income is called the

“gross profit margin”.

Second, if OE are included, then subtract OE from gross profit to get net profit or net

loss (which is also called net income). Net means the expenses have been subtracted.

The ratio of net profit over gross revenues is called the “operating profit margin”. It is

generally recommended to include these in your calculation.

4) For investors, or if management desires, a fourth step can be included which involves

subtracting any preferred dividends that will be paid (since these will reduce cash on-

hand) and then adding back any depreciation or other non-cash charges to earnings

after taxes. The result is called “net cash flow”, also called “free cash flow”.

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

5) After estimating cash flow, a final step that can be added is estimating interest and taxes

and then subtracting these. That leaves net profits. Again, this can be done using a

percentage of COGS.

In NPV, risk is estimated as best as possible – which is a polite way of saying a guestimate is

made – or an NPD-specific rule of thumb is used. Three rules of thumb are commonly used if

the anticipated value of project does not justify a comprehensive ground-up analysis.

The first rule of thumb is to use the discount rate which would be applied to an alternative

venture, such as investing the money in a stock in an equivalent company developing, making,

and/or selling similar goods. The problem with this rule of thumb is uncertainty about whether

your NPD is riskier or less risky, so it can be a crude substitute.

A second rule of thumb is to use the firm's reinvestment rate. The reinvestment rate is the

average rate of return for the firm's investments in other NPD programs in the past, or return on

very similar NPD projects. This approach reflects the opportunity cost of investment in NPV,

rather than the likely lower cost of capital of the alternative investments. But as mentioned

before, this rule of thumb suffers from the fact this is a generalized risk rate and not one that is

specific for this NPD initiative. Further it assumes the entity has a track record based on

previous NPD projects.

The third rule of thumb for calculating a discount rate is to use a rate a venture capitalist might

rely on when making an investment in a company, based on your Business Model Canvas and

staff and company or organization’s experience. These rates are adjusted up or down each

period in light of the technology readiness level (TRL) of the product or service for the

appropriate stage of NPD. This is our preferred rule of thumb if the NPD project does not justify

the time and expense of making a ground-up estimate. Figure 4 is an example of such discount

rates and the rationales for selecting each rate. It was developed using data in Richard

Razgaitis’ book Early-Stage Technology: Valuation and Pricing.

5

As this book was published in

1999, it makes sense to confirm the rates you choose to use by interviewing some venture

capital firms in your country and doing web research.

5

Richard Razgaitis, Early-Stage Technology: Valuation and Pricing (Wiley, 1999).

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

Figure 4: Discount rates from venture capital. Figure courtesy of Foresight Science & Technology.

If inflation is a significant factor, you can usually find inflation figures from a government or

financial sector website. This information is then added into the results.

If you are using ground-up estimates instead of using a rule of thumb for the discount rate, then

the ground-up estimates of the discount rate must include four factors. The first is anticipated

inflation, which is simple and considered a macro level risk. The last three are intrinsic to the

specific NPD initiative. They are execution, co-innovation, and adoption risks. These need to be

calculated and combined as discussed above. The Gate Progress Review Tool can be used to

support a ground-up determination of the discount rate.

Now turn to the NPV Tool spreadsheet itself and start entering cash flows and discount rates.

Before doing that, remember that unlike the other tools in this NPD Toolkit, the spreadsheet in

the NPV Tool almost always needs to be modified to fit the specifics of your project. A

discussion of how to modify the Tool is provided later in this description. Another option is to use

one of the many NPV tools you can find through web searching, should that fit your needs

better. Yet another option, if you are familiar with Microsoft Excel, is to build a new spreadsheet

and use the NPV and Internal Rate of Return (IRR) formulas built into Excel to calculate those

values. As always, remember that whatever spreadsheet or calculator you use, it is critical to

document your assumptions at every step. As noted previously, the NPV Tool workbook

provides a tab entitled “Assumptions and notes”, where you can enter the assumptions, data

used for calculations, data sources, etc., that you used for the calculations carried out on the

“NPV – single rate” tab. Otherwise, a viewer cannot understand why those numbers have been

entered into the spreadsheet, and why you obtained the results shown on the spreadsheet.

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

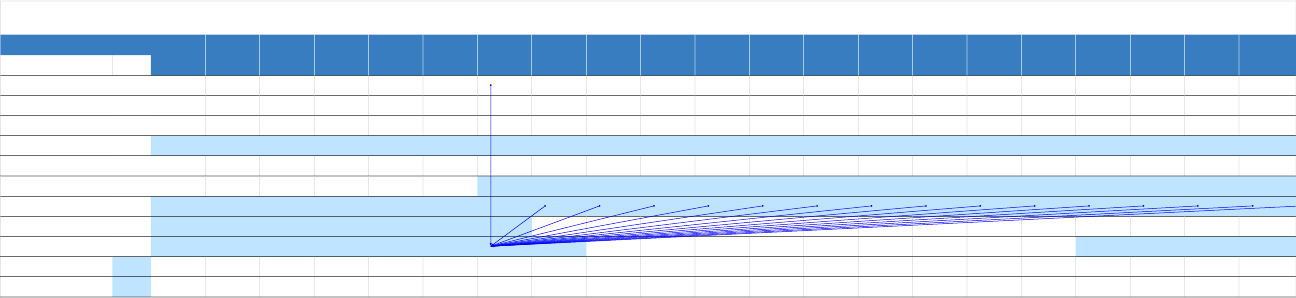

Figure 5 below depicts the NPV Tool spreadsheet for the Biofuels Example. This is a long spreadsheet, so the images pasted into

this discussion are sometimes hard to read. If you open the Biofuels Example workbook for the NPV Tool on your own computer, you

can follow the steps described below using a bigger image.

Note the tab labeled “NPV – single rate”. This means only one discount rate is used for all the periods as opposed to allowing the

discount rate to vary depending on the unique risks of each period. This highlights the fact that the Tool uses a single discount rate

for each calculation of NPV. This means the NPV for all future cash flows in the spreadsheet as of the specific period (the column) for

which the calculation is being made, is based on using a single discount rate.

In the Figure 5a (below), note that a series of discount rates have been entered in the columns along row 4 “Discount rate” for each

stage (Idea, Screening, Design, Development, Test, Launch, and Post-launch). These are estimated discount rates. They could also

be target rates. Because this is a single rate NPV, the calculated NPV value shown on row 12 of a specific column is the value of all

the future cash flows, going forward from that period, discounted only by the discount rate entered in row 4 of that same column. This

is important because the calculated NPV value in this tool is a single-rate calculation, and the forward calculations are a series of

single-rate calculations.

Alternatively, you could delete every discount rate and NPV for future columns. It would not affect the rate for the current column of

interest, as seen in the other clip in Figure 5b. However, doing so would necessitate rebuilding the spreadsheet.

Figure 5a: NPV Tool workbook for the Biofuels Example. In this clip of the spreadsheet there are additional discount rates entered as targets for future gate

reviews.

Stage Idea Screening Design Development Development Test Launch Post-launch

Period Half-year

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Discount rate

75.0% 50.0% 45.0% 35.0% 20.0% 15.0% 10.0% 5.0% 20.0% 75.0% 100.0%

Units sold

0 0 0 0 0 0 5 20 30 40 40 40 45 45 45 40 40 20 5 5 0

Average revenue/unit 0

0 0 0 0 0 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 400,000 400,000 300,000 300,000 300,000 300,000 260,000 0

Revenues 0 0 0 0 0 0 2,750,000 11,000,000 16,500,000 22,000,000 22,000,000 22,000,000 24,750,000 18,000,000 18,000,000 12,000,000 12,000,000 6,000,000 1,500,000 1,300,000 0

Average cost of goods/unit

0 0 0 0 0 0 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 0

Expenses

25,000 50,000 100,000 300,000 500,000 50,000

1,250,000 5,000,000 7,500,000 10,000,000 10,000,000 10,000,000 11,250,000 11,250,000 11,250,000 10,000,000 10,000,000 5,000,000 1,250,000 1,250,000 0

Gross profit

(25,000) (50,000) (100,000) (300,000) (500,000) (50,000)

1,500,000 6,000,000 9,000,000 12,000,000 12,000,000 12,000,000 13,500,000 6,750,000 6,750,000 2,000,000 2,000,000 1,000,000 250,000 50,000 0

Investment to date

(25,000) (75,000) (175,000) (475,000) (975,000) (1,025,000)

475,000

Net present value 27,349 1,224,061 2,960,717 26,736,051 42,268,339 59,144,750 71,803,699 243,056 28,571 0 0

Total gross profit (not discounted)

83,775,000

Internal rate of return

101%

Net present value (NPV) calculator

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

Figure 6b: NPV Tool workbook for the Biofuels Example. In this clip these discount rates and the NPV calculations for future periods are deleted. Note the NPV for

period zero has not changed as this is a single rate calculation. Therefore, deleting the discount rates and NPV for future periods is not recommended as that

necessitates rebuilding the spreadsheet.

To use the Tool, first enter the NPD stage names in columns in row 2. These column labels will refer to what NPD stages are being

conducted and completed in the period of each column. The blank worksheet is pre-populated with standard NPD stage names. In

this tool, NPV calculation requires each period to be identical. This example uses periods of half-years (6 months), but the period

(see cell B3) can be defined as required to fit the gates defined for your project. This spreadsheet has 21 periods. It begins with

period 0, where period 0 represents the start of the NPD initiative. In the Biofuels Example, period 0 is the beginning of the Idea

stage.

Next enter the anticipated discount rate for the period in which you are making the NPV calculation. If is not necessary to enter

discount rates for other periods, although you may enter them as targets for future stage-gate reviews. Again, the spreadsheet is set

up to only use the discount rate for the period you are in, for all of the out-period cash flows. In other words, the NPVs are not

cumulative. You never add results from divergent discount rates in a single rate calculation.

Next enter your cash flows. First enter the average revenue per unit; next the average cost for you to build, market and sell, and

service and support each unit for each period of the NPV calculation. If you examine the Biofuels Example you will see these

expenses vary over time as economies of scale, economies of scope and network economies kick-in. Learning curve also affects

costs. Whether your expenses will vary is determined when making your cash flow estimates.

Now, let’s look at the embedded formulas in various cells that carry out calculations. Here, consider inputs and calculations for period

0, when the NPD project is in the Idea stage. Go to cell C12 for NPV at time 0. Clicking on the “Trace Precedents” function under

“Formulas” in Excel generates what is shown in Figure 6.

Stage Idea Screening Design Development Development Test Launch Post-launch

Period Half-year

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Discount rate

75.0%

Units sold

0 0 0 0 0 0 5 20 30 40 40 40 45 45 45 40 40 20 5 5 0

Average revenue/unit 0

0 0 0 0 0 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 400,000 400,000 300,000 300,000 300,000 300,000 260,000 0

Revenues 0 0 0 0 0 0 2,750,000 11,000,000 16,500,000 22,000,000 22,000,000 22,000,000 24,750,000 18,000,000 18,000,000 12,000,000 12,000,000 6,000,000 1,500,000 1,300,000 0

Average cost of goods/unit

0 0 0 0 0 0 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 0

Expenses

25,000 50,000 100,000 300,000 500,000 50,000

1,250,000 5,000,000 7,500,000 10,000,000 10,000,000 10,000,000 11,250,000 11,250,000 11,250,000 10,000,000 10,000,000 5,000,000 1,250,000 1,250,000 0

Gross profit

(25,000) (50,000) (100,000) (300,000) (500,000) (50,000)

1,500,000 6,000,000 9,000,000 12,000,000 12,000,000 12,000,000 13,500,000 6,750,000 6,750,000 2,000,000 2,000,000 1,000,000 250,000 50,000 0

Investment to date

(25,000) (75,000) (175,000) (475,000) (975,000) (1,025,000)

475,000

Net present value 27,349

Total gross profit (not discounted)

83,775,000

Internal rate of return

101%

Net present value (NPV) calculator

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

Figure 7: Tracing precedents for the formula in cell C12 for NPV as calculated for period 0, in the NPV Tool workbook for the Biofuels Example.

The formula in the Biofuels Example for cell C12 is reproduced below from the entry line at the top of the spreadsheet:

=NPV(C4,D10,E10,F10,G10,G10,H10,I10,J10,K10,L10,M10,N10,O10,P10,Q10,R10,S10,T10,U10,V10,W10)+C11

The first item after the parenthesis is a reference to cell C4, the cell which contains the discount rate assigned for period 0. This 75%

rate is being applied to all the estimated future cash flows because at this time the risk has not been brought down further. Only one

rate is applied to all future cash flows for the NPV as of period 0, which is why this tab is entitled “NPV – single rate”.

Now look at the links to the future cash flows in Figure 6. Note that these links go out to the end of the periods for which cash flows

are being estimated, which in this case is period 20.

Because this method involves calculating at the end of the period, after making the calculation in this spreadsheet, until break-even is

reached, it is necessary to include the net of investment and revenues for the just ended current cash flow period as we have

negative cash flow for the period. That means additional investment in the project is required to cover the loss. This is seen in the last

entry in the formula, which is +C11 to add the amount of investment to date listed in cell C11 (25,000). Please be aware the

investment to date value is not in the Excel NPV formula entry box or the formula when it runs. For that reason, investment to date

was added. Without it, the NPV is not accurate for NPD. It is not necessary to add it when there is no loss, as the investment for the

period is captured in the positive net cash flow on the “Gross profit” line (row 10).

Investments not recouped are carried forward until break-even is achieved. We see this in period 6, for example, in the NPV Tool

workbook for the Biofuels Example. At the end of the Launch stage at period 6, the sum of gross profit minus the investment to date

Stage Idea Screening Design Development Development Test Launch Post-launch

Period Half-year

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Discount rate

75.0% 50.0% 45.0% 35.0% 20.0% 15.0% 10.0% 5.0% 20.0% 75.0% 100.0%

Units sold

0 0 0 0 0 0 5 20 30 40 40 40 45 45 45 40 40 20 5 5 0

Average revenue per unit 0

0 0 0 0 0 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 400,000 400,000 300,000 300,000 300,000 300,000 260,000 0

Revenues 0 0 0 0 0 0 2,750,000 11,000,000 16,500,000 22,000,000 22,000,000 22,000,000 24,750,000 18,000,000 18,000,000 12,000,000 12,000,000 6,000,000 1,500,000 1,300,000 0

Average cost of goods per unit

0 0 0 0 0 0 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 0

Expenses

25,000 50,000 100,000 300,000 500,000 50,000

1,250,000 5,000,000 7,500,000 10,000,000 10,000,000 10,000,000 11,250,000 11,250,000 11,250,000 10,000,000 10,000,000 5,000,000 1,250,000 1,250,000 0

Gross profit

(25,000) (50,000) (100,000) (300,000) (500,000) (50,000)

1,500,000 6,000,000 9,000,000 12,000,000 12,000,000 12,000,000 13,500,000 6,750,000 6,750,000 2,000,000 2,000,000 1,000,000 250,000 50,000 0

Investment to date

(25,000) (75,000) (175,000) (475,000) (975,000) (1,025,000)

475,000

Net present value 27,349 1,224,061 2,960,717 26,736,051 42,268,339 59,144,750 71,803,699 243,056 28,571 0 0

Total gross profit (not discounted)

83,775,000

Internal rate of return

101%

Net present value (NPV) calculator

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

is positive. That means there is no more investment required and the past investment has been recouped. Figure 7 below, from the

NPV Tool workbook for the Biofuels Example, illustrates that.

Figure 8: Tracing precedents for the formula in cell I12 for NPV as calculated for period 0, in the NPV Tool workbook for the Biofuels Example. As break-even is

reached, there is no longer any initial investment to recoup and hence it is not included in the NPV formula.

For all other later periods in the Biofuels Example, since the investment to date has been recouped, investment to date amounts are

not included as inputs in the NPV formula.

When entering your own data, be aware that you may need to change the NPV formula depending on when break-even is reached. If

break-even does not occur by the end of the launch stage, you will need to copy the calculation in cell I11 (investment to date, period

6, launch stage) and paste it in row 11 for all columns to the right until the period (column) when break-even is attained, so

investment to date can be included in the formula.

By copying the cells in the last column, you can extend the spreadsheet out to further periods. If you do that, you will need to modify

the entries in the Excel formula used in row 12, using the formula entry box for Excel’s NPV formula. Here is the procedure for

modifying the formula.

Place your cursor on cell C12, the first period in which you are calculating an NPV. This is the current period (period 0) on the

spreadsheet, when the NPD project is in the Idea stage. Next, on Excel’s menu bar you should click on Formulas, then Financial, and

move the slider down so we can click on the NPV formula. That opens the input box shown in Figure 8. Use this formula to enter the

cells that have the required data if you modify the spreadsheet.

Stage Idea Screening Design Development Development Test Launch Post-launch

Period Half-year

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Discount rate

75.0% 50.0% 45.0% 35.0% 20.0% 15.0% 10.0% 5.0% 20.0% 75.0% 100.0%

Units sold

0 0 0 0 0 0 5 20 30 40 40 40 45 45 45 40 40 20 5 5 0

Average revenue per unit 0

0 0 0 0 0 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 550,000 400,000 400,000 300,000 300,000 300,000 300,000 260,000 0

Revenues 0 0 0 0 0 0 2,750,000 11,000,000 16,500,000 22,000,000 22,000,000 22,000,000 24,750,000 18,000,000 18,000,000 12,000,000 12,000,000 6,000,000 1,500,000 1,300,000 0

Average cost of goods per unit

0 0 0 0 0 0 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 250,000 0

Expenses

25,000 50,000 100,000 300,000 500,000 50,000

1,250,000 5,000,000 7,500,000 10,000,000 10,000,000 10,000,000 11,250,000 11,250,000 11,250,000 10,000,000 10,000,000 5,000,000 1,250,000 1,250,000 0

Gross profit

(25,000) (50,000) (100,000) (300,000) (500,000) (50,000)

1,500,000 6,000,000 9,000,000 12,000,000 12,000,000 12,000,000 13,500,000 6,750,000 6,750,000 2,000,000 2,000,000 1,000,000 250,000 50,000 0

Investment to date

(25,000) (75,000) (175,000) (475,000) (975,000) (1,025,000)

475,000

Net present value 27,349 1,224,061 2,960,717 26,736,051 42,268,339 59,144,750 71,803,699 243,056 28,571 0 0

Total gross profit (not discounted)

83,775,000

Internal rate of return

101%

Net present value (NPV) calculator

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

Figure 9: The Excel NPV formula entry box.

The top row of the box is the discount rate. That is found in row 4 of the spreadsheet for the relevant column.

The next set of rows in the formula box in Figure 8 is for values or the net cash flow for that period. That is found on the “Gross profit”

row of the spreadsheet (row 10). Note in the entry box in Figure 8 there are separate rows for each period’s cash flow. The first

period for discounting is the period after the period you are in. A slider on the left allows you to enter as many periods as needed.

When finished, hit enter. The formula automatically calculates the NPV using data from as many periods as you have specified.

The last two rows on the spreadsheet contain additional calculations that are useful for stage-gate reviews.

The first is the “Total gross profit (not discounted)” in row 13. This is simply the sum of the gross profits of all periods, not discounted.

For the Biofuels Example, this would be the sum of the gross profits of all 20 periods, not discounted, shown in cell B13 (83,775,000).

The second is the Internal rate of return (IRR) in row 14. The IRR is the discount rate that makes the NPV of all cash flows equal to

zero. IRR uses the same formula as an NPV calculation, only this time the NPV is set to zero and the formula is solved for the

discount rate. This rate is not adjusted for risk, inflation, or anything else. That is why it is called internal. IRRs are useful for

comparing the performance of this set of cash flows against a hurdle rate, as this IRR represents the annual rate of growth that an

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

investment is expected to generate. The hurdle rate is a financial metric set by management. It specifies the return an NPD initiative

should achieve to continue. For the Biofuels Example, this would be the IRR calculated for 20 periods, shown in cell B14 (101%).

When you use this spreadsheet for your own projects, follow this approach:

1. Figure out in which periods the various stages of NPD will end.

2. Modify the formulas discussed above to reflect this shift. Copy a cell with an “Investment to date” (in row 11) until you reach a

column where the investment to date is positive, indicating the investment has been recouped and you have hit break-even.

At that point, cease adding that adjustment into the formula. If you want to calculate NPV for any period not currently in the

spreadsheet, click on Formulas, select the drop-down menu for financial formulas, and select NPV. Then complete the pop-

up box as explained above.

3. Modify the formula for “Total gross profit (not discounted)” to include any added periods beyond period 20 (i.e. columns

beyond column W).

4. Modify the formula for IRR to include any periods beyond period 20.

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

How do you interpret the data in the Net Present Value Tool and

use it in your NPD process?

The first task before interpreting any data in any NPV calculation is to determine whether the

assumptions behind it seem reasonable. The second task is making sure you do not have a

spreadsheet error. Click on Formulas, then Trace Precedents to check the assumptions that

went into the formulas you used, and to check for potential error in the formulas themselves.

Only then can you interpret the results and use them in a stage-gate review.

The assumptions behind the data for the Biofuels Example using this tool should be considered.

There is a very high discount rate for the Idea stage. All things being equal, this would normally

be a showstopper. In this case, however, assume the cost for the Idea stage is low enough that

management decided to continue because of a commitment to building a greener economy and

greater energy independence for their country.

In this spreadsheet, there is no further calculation of discount rate after the Post-launch stage

until near the end of the 10 years over which the spreadsheet runs. The assumption behind this

is that for periods 17 through 19, hitting market saturation during this time was anticipated, after

which sales become harder to find. Assume it will be necessary to introduce an improved unit

before then, as per the NPD portfolio, so any sales of the older model would only involve using

up remaining previously purchased parts inventory.

Interpreting the results is a matter of seeing if the NPV you calculate is acceptable. At a gate

review, the next step is to estimate what the discount rate is anticipated to be at the end of the

next stages. If those are also acceptable, that is probably a good sign that you can safely

proceed. If both the current and future NPVs look good or are otherwise acceptable, you would

probably decide to go forward into the next stage. If the NPV for the current period or future

ones looks bad, figure out why and see if risk mitigation can reduce the discount rate by

reducing the risk-associated factors that go into estimating the discount rate. The Life Cycle

Risk Reduction Tool is helpful for exploring ways to modify the Action Plan in order to reduce

risk. The Gate Progress Review Tool is useful for assessing the impact on the discount rate of

any changes in the Action Plan.

When the results in the Biofuels Example spreadsheet for this tool are interpreted, it seems that

a Go decision at some of the early gates, such as the decision to move from the Idea stage to

the Screening stage, is a reasonable high risk, high reward decision. Management has

accepted the high risk for the early stages so long as the rewards look excellent. The

calculations of high gross profit and internal rate of return support an expectation of high reward.

Of course, the decision to move forward at any gate would depend on whether the cost for the

next stage was low enough that management could afford, and was willing, to continue

investing even if the project was terminated at the end of that next stage. Assuming the NPD

team can demonstrate a strong anticipated competitive advantage, that would help the project

make it through this next gate because the anticipated advantage supports the expectation of

attaining high returns. A good likelihood of winning a government grant to fund R&D would also

support a Go decision. If the cost of development is zero and the market prognosis is good, that

would provide a strong reason to continue.

Pre-published version. Not for further distribution

When using the Tool for your own NPD project, be aware that you can run various scenarios

based on various sets of assumptions. It is recommended to run at least three scenarios

including a most likely scenario, a best-case scenario, and a worst-case scenario.

The point of this exercise is to explain and illustrate that the numbers entered into the NPV Tool

spreadsheet have to make sense in light of what is happening in the entity carrying out NPD, in

the market, and in the larger environment. If you write down and explain your assumptions, then

a viewer can either agree or disagree with them. If they disagree with your assumptions, they

can ask you to use different numbers and run that scenario.