Appraisal Methods

Basic information and

procedures for setting up

a mass appraisal program

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17)

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Table of contents

Chapter Title Pages

Foreword

1 Introduction to the Property Tax System ........................................1–1

2 Organization and Administration ..............................................2–1

3 Records .....................................................................3–1

4 Oregon Cadastral Map System .................................................4–1

5 Fundamental Appraisal Concepts ..............................................5–1

6 The Three Approaches to Value ................................................6–1

7 Statistics and Appraisal Standards .............................................7–1

8 Mass Appraisal of Land .......................................................8–1

9 Mass Appraisal of Residential Properties ........................................9–1

10 Mass Appraisal of Income–Producing Properties ................................10–1

11 Mass Appraisal of Farm and Ranch Properties ..................................11–1

12 Common Ownership Properties ..............................................12–1

13 Maximum Assessed and Assessed Value .......................................13–1

14 Other Assessment Programs ..................................................14–1

15 Property Tax Appeals ........................................................15–1

16 Glossary ...................................................................16–1

17 Index ......................................................................17–1

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Foreword

Appraisal Methods for Real Property

This manual provides county assessors and their staffs with the basic information and procedures to set

up and maintain a mass appraisal program for property tax purposes. A well-run appraisal program

benefits and serves all those who pay property taxes in Oregon.

The International Association of Assessing Officers defines mass appraisal as:

“. . . the systematic appraisal of groups of properties as of a given date using standardized procedures and statistical

testing.”

By following the guidelines in this manual, it is possible to achieve accurate, persuasive, and defendable

appraisals to use as the basis for property tax assessment. The cost of estimating property value using

other methods would be prohibitive and not in the best interest of the public.

This manual reflects laws and Department of Revenue policies that were current at the time of

publication. In addition to other publications, we have utilized the following sources to produce this

manual:

Property Assessment Valuation, Third Edition, IAAO, 2010

The Appraisal of Real Estate, 14th Edition, The Appraisal Institute, 2013

The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, Sixth Edition, The Appraisal Institute, 2015

Note: Although this manual reflects laws and policies that were current as of the revision date, a

substantial number of the forms and examples included in the manual haven’t been updated since the

time of the last major revision in 2003. Be assured this doesn’t invalidate the manual as an effective

training tool for appraisers in the assessment field.

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Chapter 1

Introduction to the Property Tax System

Oregon’s property tax system supplies revenue that funds services provided to citizens. In recent years,

Oregon voters approved two significant property tax limitations, yet revenue generated by property tax

is second only to personal income tax revenue. For the 2014–15 tax year, property taxes raised more than

$5.7 billion for local governments.

This chapter summarizes the assessment program and tax collection process.

Legal basis for assessment

ORS 307.030 states:

• All real property within this state and all tangible personal property situated within this state,

except as otherwise provided by law, shall be subject to assessment and taxation in equal and ratable

proportion.

• Except as provided in ORS 308.505 to 308.681, intangible personal property isn’t subject to assessment and taxation.

Oregon has an ad valorem taxation system. The taxation system is based on the value of property. The

amount of property tax an owner of a property will pay is determined by:

• The taxable assessed value of the property;

• The total of the tax levies imposed by the taxing districts in which the property is located; and

• Constitutional tax limitations.

Imposition of tax

A taxing district collects property tax dollars by imposing a levy. Property tax levies are either rate-

based or amount-based. Most taxing districts impose rate-based levies for at least some of their operating

revenues. The rate for most districts is limited by an amendment to Oregon’s constitution referred to as

the permanent rate limit. Districts can levy a tax rate every year that is less than or equal to this limit

without additional voter approval. Amount-based levies are usually bond levies or local option levies that

have been approved by the voters of a taxing district for a fixed dollar amount per year. Bond and local

option levies are in addition to the permanent rate levy. Local option levies can be either rate-based or

amount-based. When a taxing district imposes an amount-based levy, the county assessor converts the

amount levied into a tax rate by dividing the levy amount by the total assessed value in the district.

Role of the Department of Revenue

The Department of Revenue supervises the administration of the property tax system in Oregon. ORS

306.115 states:

“The department may do any act or give any order to any public officer or employee that the department deems

necessary in the administration of the property tax laws so that all properties are taxed or are exempted from

taxation according to the statutes and Constitutions of the State of Oregon and of the United States.”

In partnership with the counties, we:

• Train and provide technical assistance for county staff;

• Write administrative rules and legislative concepts;

• Advise the counties regarding property tax issues;

• Review the assessors’ certified ratio studies;

• Hold property tax supervisory and merits conferences; and

• Respond to questions from taxpayers.

1-1

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

We are responsible for appraising and maintaining the inventory of large industrial improvements

valued at over $1 million. The inventory of state appraised industrial property is updated annually

through the state’s Industrial Property Return, 150-301-032. The property that must be reported on the

return includes buildings and structures, yard improvements, machinery and equipment, and personal

property.

The department is also responsible for appraising and developing the inventory of all centrally assessed

property. Centrally assessed property includes utility property, railroads, and airlines.

Summary of the assessment program

The assessment program is the foundation of the property tax system in Oregon. Each county has an

elected or appointed assessor who administers the program at the local level. The assessor has the

responsibility to discover, list, and value both real and taxable personal property according to the

following guidelines.

Assessment date

ORS 308.210(1) describes the “assessment date” and states in part:

The assessor shall maintain a full and complete record of the assessment of the taxable property for each

year as of January 1, at 1:00 a.m.

Frequency of appraisal

From 1955 to 1996, the assessor was required by law to physically reappraise all property in the

county every six years. This requirement was eliminated in 1997 for various reasons including budget

constraints, accelerated appraisal techniques, and the successful application of computerized valuation

programs. Current law requires that each parcel of real property be appraised using a method of

appraisal approved by our administrative rule. See ORS 308.234.

Duties of assessor

The major duties of the county assessor are:

• Locate and identify each property.

• Inventory each property.

• Classify each property.

• Estimate the real market value (RMV) of each property.

• Calculate the taxable value of each property.

• Prepare and certify the assessment roll for the county.

• Calculate the tax due for each property.

• Respond to all property value appeals.

Locate and identify each property

To locate and identify property, the assessor needs an adequate mapping system that shows each parcel

of land in the county.

After the assessor receives notice of the existence of new property, the assessor must describe the

property to make an assessment. This is achieved through a parcel numbering system, referred to as

cadastral mapping, in which each property is assigned its own identifier. (See Chapter 4 for more details.)

1-2

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Inventory each property

Except for large industrial and utility property, the assessor is responsible for maintaining the inventory

of land, buildings, and other improvements attached to the land throughout the county. Maintaining the

inventory of real property requires an on-site inspection. During the inspection, the appraiser records the

following information about the land and improvements:

• Size;

• Quality;

• Condition; and

• Other pertinent data.

The assessor updates the inventory through additional physical inspections whenever new construction

is discovered.

The assessor’s staff develops an inventory of taxable personal property from annual returns filed by

the property owner or the person in possession of the property. The return filed with the assessor is

called a Confidential Personal Property Return, 150-553-004. The assessor may choose to perform an on-site

inspection of the property to confirm the inventory. For more information about how the assessor values

personal property see: Methods for Valuing Personal Property, 150-303-450, and Personal Property Valuation

Guidelines, 150-303-441.

The inventory of county appraised industrial property is updated through the county’s Real Property

Return, 150-301-031. The property that must be reported on the return includes buildings and structures,

yard improvements, machinery and equipment, and land site development. Just as for personal property,

the assessor may choose to perform an on-site inspection to confirm the inventory reported in the return.

Classify each property

Each property in the county must be classified according to its taxable status and property type. OAR

150-308-0310 contains the basic property class codes that the assessor must use to classify property.

Correct classification ensures that property receives the correct annual adjustment or exemption from

taxation.

In Oregon, the basic property classes are:

0. Miscellaneous 5. Farm

1. Residential 6. Forest

2. Commercial 7. Multi-family

3. Industrial 8. Recreation

4. Tract 9. Exempt

There are sub-classes to further identify property.

Estimate real market value (RMV)

Oregon law requires all real or personal property that isn’t exempt from ad valorem taxation or subject to

special assessment be valued at 100 percent of its RMV. RMV is defined in ORS 308.205:

(1) Real market value of all property, real and personal, means the amount in cash that could

reasonably be expected to be paid by an informed buyer to an informed seller, each acting without

compulsion in an arm’s-length transaction occurring as of the assessment date for the tax year.

(2) Real market value in all cases shall be determined by methods and procedures in accordance

with rules adopted by the Department of Revenue and in accordance with the following:

1-3

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

(a) The amount a typical seller would accept or the amount a typical buyer would offer that could

reasonably be expected by a seller of property.

(b) An amount in cash shall be considered the equivalent of a financing method that is typical for a

property.

(c) If the property has no immediate market value, its real market value is the amount of money that

would justly compensate the owner for loss of the property.

(d) If the property is subject to governmental restriction as to use on the assessment date under

applicable law or regulation, real market value shouldn’t be based upon sales that reflect for the property

a value that the property would have if the use of the property weren’t subject to the restriction unless

adjustments in value are made reflecting the effect of the restrictions.

The RMV of all taxable property in the state is updated annually through various methods of appraisal,

the Assessor’s Certified Ratio Study, and application of computerized trending or recalculation.

Calculate taxable value

The law defines taxable assessed value as the lesser of a property’s maximum assessed value (MAV)

or RMV. Assessed value (AV) is the value upon which taxes are based. MAV was created through an

amendment to the constitution (Measure 50) passed by Oregon voters in 1997. MAV was defined for the

1997–98 tax year as the 1995 RMV reduced by 10 percent. For the years following 1997–98, MAV is equal

to the greater of 103 percent of the prior year’s assessed value or 100 percent of the prior year’s MAV. See

ORS 308.146.

The law allows MAV to be adjusted above three percent only for specific reasons that are referred to as

“exceptions.” Exceptions are discussed in Chapter 13 of this manual.

The assessor must keep additional values on the roll for specially assessed property.

Prepare the assessment roll

The product of the assessor’s work is an annual assessment roll. The roll is the basis for the levy of taxes

that will be collected annually. The roll contains information about each property including:

• The name of the owner;

• A description of the property by code area and account number;

• The property class;

• The number of acres;

• The RMV of the land;

• The RMV of the buildings;

• The taxable status of the property; and

• The total AV, MAV, and RMV of the property.

See ORS 308.215 for a complete listing.

Calculate the tax

Typically, the assessor calculates the taxes due against a property by multiplying the AV of the property

by the tax rate of the taxing districts in which the property is located. However, if the amount of tax

calculated by this method is higher than the Measure 5 constitutional limits allow, the taxes due against

a property must be compressed. In such a situation, the tax is under “compression” and is calculated

by multiplying the RMV of the property times the constitutional limits of $5 per $1,000 of RMV for the

education category and $10 per $1,000 of RMV for the general government category.

The assessor knows if the tax for a property is under compression by applying the “M5 test.” The M5 test

checks the taxes to be billed against the $5 and $10 category limits. If the taxes are less than the limits, the

taxes will be billed without compression. If the taxes to be billed are more than either the $5 limit or $10

1-4

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

limit, the taxes will be reduced until they fit under the limitation. The M5 test is applied to every taxable

property in the county.

After the taxes are computed for each property tax account, the assessment roll is certified to the tax

collector and becomes the tax roll. In some counties, the assessor may also be the tax collector.

Respond to property value appeals

The result of each assessment is a tax bill. If a property owner disagrees with the assessor’s estimate of

value, the owner may appeal the value to their local board of property tax appeals (BOPTA). The value

of state–appraised industrial property must be appealed to the Magistrate Division of the Oregon Tax

Court. Centrally assessed property is appealed to our director. An appeal of a penalty assessed for the

late filing of a real, personal, or combined industrial property return must be filed with BOPTA even if

the value of the property has to be appealed to the Magistrate Division.

The appeal process allows property owners the opportunity to ensure their property is valued correctly

and in accordance with statutory provisions. If the taxpayer or the assessor disagrees with the board’s

decision, either one may appeal to the Oregon Tax Court.

The assessor may respond to appeals at each step in the appeal process. See Chapter 15 for a complete

discussion of appeal procedures.

Role of the tax collector

The tax collector bills and collects all taxes and makes periodic remittances of collections to taxing

districts. The tax collector mails tax statements to property owners on or before October 25 of each year.

The statements contain the RMV and AV of the property and the taxes imposed for each taxing district.

The statements also indicate any delinquent taxes from previous tax years.

Taxes are levied and become a lien on property on July 1. Tax payments are due November 15 of the same

calendar year. Taxpayers may elect to pay their property taxes in three equal payments:

• First payment due November 15;

• Second payment due February 15; and

• Final payment due May 15.

The taxpayer receives a 3 percent discount if full payment is made by November 15 or a 2 percent

discount if two-thirds is paid by November 15. For late payments, interest accrues at a rate of 1-1/3

percent per month.

If the property is real property, taxes become delinquent if not paid in full by May 15. Foreclosure

proceedings begin if taxes are unpaid after three years. Foreclosure is the legal process a county uses to

acquire title to property. After foreclosure, the property can be sold to satisfy the tax debt.

If the property is personal property, taxes are delinquent immediately after any required payment is

missed. Counties are required to issue warrants for collection 30 days after delinquency and may seize

the property for collection at any time after delinquency.

1-5

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Chapter 2

Organization and Administration

Organization

The organization of an assessor’s office is determined by the type and volume of work that must be

completed. The larger the staff, the greater the need for a formal organization plan. Small offices are

organized less formally than large offices, but a division of responsibility still needs to be identified so

the office runs smoothly.

The following chart outlines the organization generally found in an assessor’s office. It can be modified

to fit any county’s requirements.

Assessor’s oce organization chart

Information

Systems Unit

Assessor

Chief

Cartographer

Chief Appraiser

Office Mgr. /

Chief Deputy

Data Analyst

Cartographer Data Entry Accounting

Clerical & Special

Programs

Residential Commercial Farm Industrial

Personal

Property

To accomplish work objectives, the assessor establishes a line of authority. Each person should know his

or her position description and supervisor. Each supervisor needs to know the employee(s) he or she

supervises. No person should have more than one direct supervisor. This avoids conflicting instructions

that could lower efficiency and morale. Responsibilities shouldn’t be delegated to a supervisor without

the accompanying authority to carry out the necessary duties.

2-1

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Positions commonly found in an assessor’s office and the duties of those positions are:

Assessor—Establishes the procedures and manages an organization that complies with the provisions of

the law relating to the assessment of property. As administrator, the assessor is responsible for all work

performed by the staff. The assessor needs to know the statutory requirements and steps involved in the

assessment process. The assessor plans, organizes, coordinates, and directs all the office functions.

Chief deputy/Office manager—Supervises office functions; helps develop office policy and programs;

establishes and maintains the records system; and acts for the assessor in the assessor’s absence.

Office support—The amount and type of support needed varies with the size of the county. Common

positions are file clerk, program support, and data entry clerk. Duties for these positions vary but most

include assisting the public.

Chief appraiser—Establishes appraisal objectives and directs the appraisal program; plans and develops

appraisal policy; coordinates the various appraisal sections; and develops the staff training program.

Chief cartographer—Supervises the maintenance of the cadastral mapping program.

Supervising appraiser—Supervises a staff of appraisers; supervises preappraisal set-up studies;

appraises the larger and more complex properties; conducts field reviews of completed appraisals for

quality, uniformity, and equity; and monitors appraisal progress to meet the established appraisal

objectives.

Data analyst—Collects, confirms, and records market data of all types; develops the ratio study;

maintains the sales database; and provides market analysis for the appraisal staff.

Field appraiser—Establishes the RMV of the majority of the properties in the county. The success of most

other functions of the assessor’s office depends on the quality and quantity of the field appraiser’s work.

Information systems unit manager—Sometimes referred to as the information technology (IT) manager

or data processing (DP) manager. Maintains, updates, and coordinates the computer programs and the

assessment and taxation records through the use of a mainframe computer, local area network, and

personal computer, or any combination of the three.

Administration

Assessment time line

The assessment year begins on January 1 and ends on December 31. The assessor must complete many

tasks throughout the year according to a specified timeline. The following assessment calendar includes

the most important deadlines that affect the assessor’s workload. These dates are either required by

statute or recommended by us.

January

1 Assessment date for most real and personal property (ORS 308.210).

1 Beginning of sales collection year (ORS 309.200).

31 Last day for nonprofit homes for the elderly to notify the assessor that veterans have been given

property tax credit (ORS 307.385).

February

Board of Property Tax Appeals (BOPTA) convenes on or after the first Monday of month (ORS 309.026).

2-2

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

March

1 Assessor sends income questionnaire to owners of non-exclusive farm use (EFU) farmland (OAR

150-308-1050).

15 Last day to file personal property and/or industrial real or combined returns (ORS 308.290).

31 Last day for taxing district to file boundary description and map changes with us (ORS 308.225).

April

1 Filing deadline for most exemptions and special assessments.

10 Assessor sends written notice of late filing to veterans or the surviving spouse (ORS 307.260).

15 BOPTA must adjourn (ORS 309.026).

15 Last day owner of non-EFU farmland can file for farm use assessment of wasteland or land under

farm use dwellings (ORS 308A.074 and ORS 308A.253).

15 Deadline for owner of non-EFU farmland to provide income information requested by the assessor

(OAR 150-308-1050).

May

1 Last day certain veterans or the surviving spouse can file for exemption (must pay a late fee) (ORS

30 7. 26 0).

1 CAFFA grant applications due to us (ORS 294.175).

June

1 Last day to file a personal property return with the assessor and receive a 5 percent penalty on the

tax (ORS 308.296).

1 Deadline for county to file an amended CAFFA grant application that includes a revised estimate of

expenditures.

15 We issue CAFFA certification letters to the county governing body. (ORS 294.175).

30 Last day (or 60 days after property destroyed or damaged) for owner to file application with county

tax collector for proration of taxes for property destroyed or damaged by fire or act of God (ORS

308.425).

30 End of the tax/fiscal year (ORS 308.007).

30 Last day for BOPTA to issue amended orders (ORS 309.110).

30 Last day for five or more taxpayers owning in the aggregate 5 percent or more of total forestland in a

land market area to appeal specially assessed forestland values (ORS 321.219).

30 Our industrial values due to county (OAR 150-306-0110).

July

1 Start of tax/fiscal year (ORS 308.007).

1 Last day to submit Assessor’s Certified Ratio Study to us or request an extension in writing (OAR

150-309-0250).

1 Lien date for real and personal property (ORS 311.405).

1 Assessment date for damaged or destroyed property if application filed timely [ORS 308.146(6)].

1 Prepayment of taxes on subdivisions and condominiums (ORS 92.095 and ORS 100.110).

2-3

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

August

1 Last day to submit ratio study to us if extension has been granted [OAR 150-309-0250].

1 Last day, or 60 days after property destroyed or damaged, for owner to file application for July 1

reassessment without paying a late fee.

1 Last day for owners of land disqualified from special assessment as farm, forestland, or wildlife

habitat to file for a different special assessment if disqualification occurs on or after January 1 and

before July 1 (ORS 308A.724).

1 Last day for Servicemembers to file claim for Oregon Active Military exemption for tax year ending

on previous June 30. (ORS 307.289)

1 Last day to file a personal property return with the assessor and receive a 25 percent penalty on the

tax (ORS 308.296).

2 Penalty for failure to file personal property return becomes 50 percent of the tax (ORS 308.296).

14 Last day assessor mails notice of disqualification for “no longer in use” farm or forestland (ORS

308A.113; ORS 308A.116; ORS 321.822). Owner has 30 days from date of disqualification notice to file

for a different special assessment (ORS 308A.724).

September

1 Last day for us to issue Assessor’s Certified Ratio Study findings and recommendations to the

assessor and the county governing body.

1 Last day for filing for tax deferral on farm use land in a disaster area (ORS 311.745).

25 Assessor’s last day to change values on assessment roll except for allowed reductions (ORS 308.242).

25 Assessor certifies value or value estimate of joint taxing districts

(ORS 310.110).

October

Assessor delivers roll and warrants to tax collector at such time as necessary to enable mailing of tax

statements by October 25 (ORS 311.105 and ORS 311.115).

1

Assessor notifies us of new industrial accounts that should become state responsibility. (OAR

150-306-0100).

15 Assessor files ratio study with BOPTA clerk (ORS 309.200).

25 Last day to mail tax statements (ORS 311.250).

The day after tax statements are mailed, the county clerk begins to accept petitions for reduction in value

(ORS 309.100).

November

1 Last day for assessor to submit appraisal plan to us if not submitted with ratio study (our policy).

4 Last day for assessor to submit a certified copy of roll summary (SAL Report) to us (ORS 309.330).

15

Property tax due (ORS 311.505).

30 Last day for assessor to mail notice of increase of current year values (ORS 311.208).

2-4

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

December

1 Enterprise zone report due from assessor to us (ORS 285B.695).

15 Last day to file application for designation as forestland due to any increase in assessment (ORS

321.358).

15 Last day to requalify non-EFU zoned farmland disqualified for lack of income. Late fee required

(ORS 308A.089).

31 Last day to file for exemption with a late filing fee (ORS 307.112, ORS 307.162, ORS 307.166).

31 Last day to apply for open space land assessment (ORS 308A.306).

31 Last day to file for riparian land exemption (ORS 308A.356).

31 Last day to file appeals to BOPTA (ORS 309.100).

31 End of sales collection year (ORS 309.200).

31 Last day for assessor to reduce value (ORS 308.242).

31

Last day to apply to assessor for correction of maximum assessed value (MAV) based on error in

square footage or exception added in error (ORS 311.234).

31 Last day to apply to have destroyed or damaged property redetermined as of July 1 with payment of

a late fee.

31 Last day owner can apply to have the MAV of property reduced due to demolition or removal.

2-5

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Planning the mass appraisal program

Supervisory oce work

Review eld and oce procedures

When planning the appraisal program, analyze the policies and procedures of the current appraisal

program by reviewing:

• Office procedures such as:

− Removal of appraisal records and field maps from the office;

− Computer access and data entry;

− Completion of appraisal work and posting progress charts; and

− Filling out work reports.

• Field procedures including:

− Appraiser identification;

− Purpose of appraisal;

− Filling out appraisal records and forms;

− Property inspection;

− Confirmation of building measurements;

− Property photos; and

− Recording data on field maps.

• Policies regarding:

− Closed gates;

− Dogs and other protective animals;

− Property hazards;

− Property visits when only minors are present; and

− General trespass.

This review ensures that current office and appraisal policies and procedures are adequate to meet

statutory compliance and program needs.

Ratio analysis

A ratio study compares the RMV of property on the tax roll to current sales prices. The conclusions

arrived at through the ratio study are used to adjust roll values to market value as of the assessment

date. Ratio studies are also used to identify areas that may need reappraisal. The assessor is required to

complete a ratio study each year. For an in-depth discussion on ratio analysis, see Chapter 7.

Reappraisal

Measure 50 eliminated regular reappraisal for many counties. Instead, most counties now conduct

“hot-spot reappraisals.” Hot spots are those areas that don’t comply with current ratio standards, have

changed dramatically since their last physical reappraisal, or in some other way indicate that reappraisal

is needed. For example:

• Coefficients of dispersion (COD) indicate a lack of uniformity.

• Sales indicate an increase in the number of accounts that are not the same as appraised.

• Appeal activity for any given neighborhood increases significantly.

• The last physical appraisal is 10 or more years old.

2-6

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Appraisal performance review

Review appraisals for acceptable quality levels. The quality of the appraisals can be measured through

field review and ratio analysis.

Develop, monitor, and summarize performance measures of the appraisal program. Such measurements

may include:

• Appraisal production per day and by each appraiser.

• Ratios and coefficients of dispersion for the appraisal area and for each appraiser.

• Number of appeals for the program and for each appraiser.

Determine workload

Next, determine the annual workload of the appraisal program. This analysis includes workload

measures for activities such as reappraisal, appraisal maintenance, special assessments, appeals,

miscellaneous time, and management and supervision. Establish geographic/physical areas with equal

workloads so that each area will require approximately the same staff resources to appraise.

Consider the number of accounts and types of property in the county, distribution of each type,

neighborhood boundaries, and relative difficulty of appraising the different property types.

Another factor is geographical distance. Allow for travel time to and from the appraisal areas and

between properties within the area. Small tracts scattered throughout an area will require much more

time per appraisal than an urban area with many similar properties located in a relatively small area.

To establish valuation areas, consider:

• Total county workload:

− Total accounts; and

− Number of accounts of each property type.

• Division of workload:

− Property class;

− Code areas; and

− Market area boundaries.

• Time required for:

− Appraisal set-up, analysis of market data, and development of value indicators;

− Appraisal production;

(Determine how long it takes to appraise one unit of each property type, then multiply by the

number of each type of property.)

− Supervisor’s field review of appraisals;

− Maintenance of appraisals due to new construction, segregation, damage and destruction,

reviews, etc.;

− Preparation and presentation of value data at various levels of the appeal process;

Establish dates throughout the coming year to periodically check the progress of the project to determine

if work will be completed on schedule. This will allow for shifting of personnel as needed to complete the

project on time.

After the supervisor gives the appraisal staff their assignments, the supervisor must monitor appraisal

progress and keep a current work report. The report usually contains information on areas being

appraised, date and time involved, miles traveled, type of property appraised, and the unit count of

land and improvements. Without a current work report, it will be impossible to forecast and refine

the timeline and number of personnel required. Work reports provide a means of assuring that the

appraisals in an area will be completed within the allotted time. By tracking work reports, the supervisor

can shift resources as needed to ensure timely completion of the appraisal area.

2-7

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Estimate sta requirements

Apply the expected production to the project’s workload to derive an estimate of time required. Convert

the time required to the number of positions to determine staff needs.

For example: the project is the reappraisal of a hot-spot residential area. Based on information from

prior work reports, determine the average time needed to appraise one unit of each property type.

Then multiply the total number of units within each property type in the appraisal area by the average

appraisal time required for one unit of that property type.

400 units, type 101 x 1.5 hours/unit = 600 hours, or 75 work days

The total time required for all property types (bare land, improved single family, duplex, triplex, and

fourplex) will determine the time and staff necessary to complete the appraisal area.

Total time required for area = 1,575 work days

Time available to appraise area = 178 days

1,575 ÷ 178 = 9 appraisers required to appraise the area.

To estimate the staff required, consider miscellaneous time such as vacations, sick leave, training, and

holidays.

The following worksheet can be used to determine:

• Staffing requirements for the year;

• Staff availability for reappraisal;

• If staffing is adequate;

• At what point additional staff may be required; or

• If part-time contract help is needed.

2-8

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

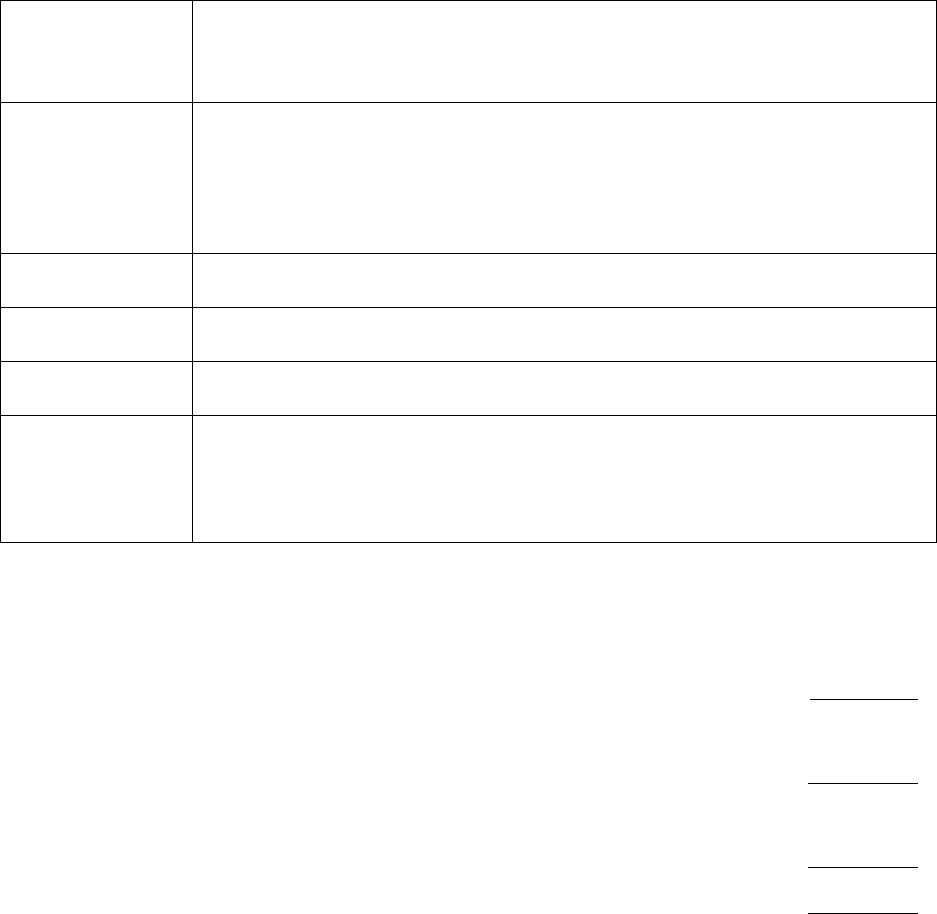

Appraisal staffing worksheet

Total number Required Estimated

Work activity of accounts production workdays

1. Maintenance

New construction, remodels, etc. __________ __________ __________

Segregations, lot line adjustments, etc. __________ __________ __________

Other __________ __________ __________

2. Reappraisal / Recalculation

Appraisal set-up studies

Residential __________ __________ __________

Commercial / Industrial __________ __________ __________

Rural __________ __________ __________

Manufactured structure __________ __________ __________

Field appraisal __________ __________ __________

3. Farm and forest use __________ __________ __________

4. Personal property __________ __________ __________

5. Exemptions, deferrals, specially assessed __________ __________ __________

6. Appeals

BOPTA __________ __________ __________

Magistrate Division—Tax Court __________ __________ __________

Regular Division—Tax Court __________ __________ __________

7. Appraisal review

Residential __________ __________ __________

Commercial / Industrial __________ __________ __________

Other __________ __________ __________

8. Miscellaneous days

Taxpayer assistance __________

Training and tech groups __________

9. Administration

Management and supervision __________

Ofce / Clerical support __________

Data analyst __________

Total days required __________

10. Non-work days

Holidays and vacation __________

Sick leave and other leave __________

Current staff ____________________ x (260 days − Non-work days) = Available days __________

If available days are equal to or greater than days required, then the proposed plan can be

accomplished with current staff. If the available days are less than the days required, then either

the plan or staffing will need to be altered.

2-9

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

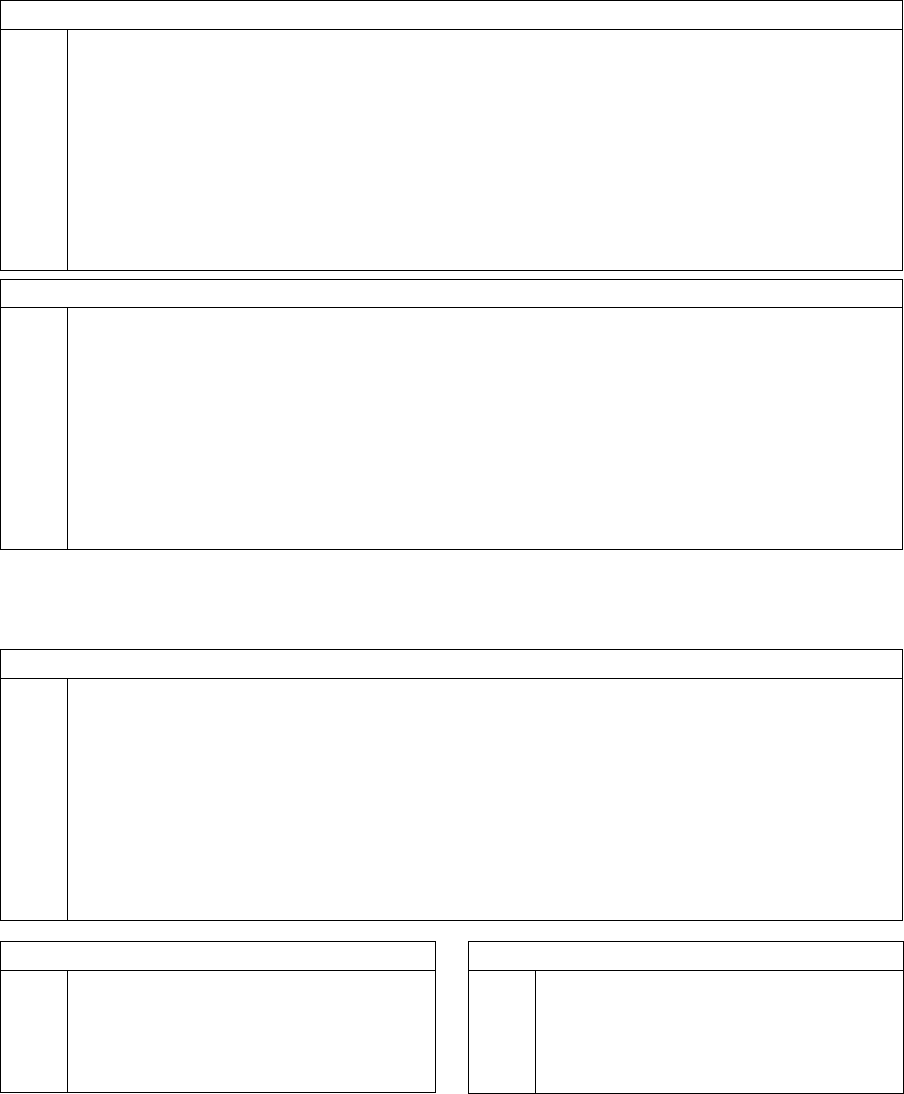

Use a worksheet like the one below to estimate the total number of full time equivalent (FTE) positions

needed to perform each separate task. To calculate the FTE, divide the total number of hours required to

perform the task by the total number of hours available during the time allocated to complete the task.

The following is an example of clerical support for processing BOPTA petitions:

Duties Unit of measurement Volume per period Estimated total

Petition 400 petitions 20 minutes each 133 hours

Misc. records Miscellaneous 50 hours 50 hours

Total hours 183 hours

Method to calculate the full-time equivalent positions

Total working hours per year

52 weeks x number days per week worked x number hours per day attendance

2,080

From total working hours per year, above, subtract the following:

Holidays per year x number hours worked per day 96

Vacation (use average number hours taken per person for prior year) 80

Sick leave (use average number hours taken per person for prior year) 40

Hours available to work in a year 1,864

Total hours = 183 183 ÷ 1,864 = 0.10 (rounded) FTE

Hours available in a year = 1,864

Supervisory eld work

It is important for supervising appraisers to conduct a field review of a representative sample of each

appraiser’s work. The review ensures that accurate inventory and uniformity of value is achieved, and

that county policy is followed.

Appraisal oce work

An appraisal is an opinion of value formed after considering many variables. In mass appraisal, variables

are measured and standards are developed for application to individual properties. This method

promotes sound RMV estimates and equality between properties.

One important requirement for achieving an accurate RMV is a current and complete data file. An

effective program of data collection and recording will improve the quality and quantity of the appraisals

and provide support for the final value conclusions.

The data file includes:

• Sales data records.

• Sales confirmation questionnaires.

• Sales data maps:

– Sales entered on maps with color-coding;

– Other appraisal data (land leases, listings, offerings, opinions, etc.) entered on map;

– Boundary lines of market areas.

2-10

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

• Current construction cost data of structures and components.

• Income and expense information:

– Income and expense questionnaires;

– Gross income multiplier (GIM) studies;

– Capitalization rate studies.

• Land data:

– Rural soil maps, aerial photos, land production records, water rights, and climate and rainfall

information;

– Urban land–use maps, facilities, zoning and building restrictions;

– Tabulations of confirmed sales of vacant parcels;

– Tabulations of land rentals (urban and rural);

– Tabulations of opinions of value, asking prices, etc.

• Building data:

– Tabulations of confirmed sales of improved properties;

– Tabulations of depreciation benchmark studies.

Valuation studies

Preappraisal set-up studies provide the basis for the mass appraisal program. These studies include:

Time trend—All data affected by inflationary or recessionary trends should be adjusted to the base

appraisal date.

Land—Sales are analyzed to develop base unit values, market adjustments and benchmarks.

Quality class benchmarks—Properties are identified that are representative of each quality class. The

properties don’t have to be sold properties.

Local cost modifier (LCM) —Information from builders, sales of new homes, building supply houses, and

government indexes are used to establish the LCM, which brings factor book costs in line with local market costs.

Depreciation—Sales, costs, and improvement residuals are analyzed to develop depreciation schedules

and benchmarks for various types of improvements.

Income and expense data—Income property information is analyzed to establish economic rents and

typical expenses.

Capitalization rates—Sales are analyzed to determine the overall rate applicable to income-producing

properties. Recapture and tax rates are extracted from the sales.

Gross income multiplier (GIM) —Analyze the sale-to-income ratio to determine the GIMs to use on

various properties.

Exception calculation

Exceptions are changes to property that allow adjustments to maximum assessed value. After a changed

property has been identified and physically inspected, calculate the RMV of the change and update the

account. Computing the exception value is a separate procedure. For more information see Chapter 13 on

“Exceptions.”

Appeals

Allocate appraisal and clerical staff time to respond to taxpayer inquiries and appeals. It is expected that

any valuation program will produce a certain number of appeals. However, well-documented supporting

data can reduce the time necessary to respond to the appeals.

Appraisers and clerical staff typically spend considerable time assisting taxpayers after the tax statements

have been mailed. Diplomatic and helpful information at this stage of the taxpayer’s inquiry into the

accuracy of their value can greatly reduce the number of appeals.

2-11

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Appraisal field work

Valuation studies

Each of the previously listed studies also requires field verification. For instance, improvement quality

and special site characteristics can be accurately determined by field inspection. In some cases, a personal

interview provides the most complete sales data and income and expense data.

Maintenance appraisal

This involves the annual appraisal of new property and changes to existing property after the January 1

assessment date.

Reappraisal

Once the preappraisal set-up studies are complete and base standards have been established, they

are applied to each property separately, taking into consideration the individual characteristics each

property may possess. By using this approach, the value indicators can be uniformly applied to a mass of

properties by following accepted appraisal principles and procedures.

Properties are inspected and data from preappraisal set-up studies are applied through the three

approaches to value to develop the final estimate of RMV for each property being appraised.

Appeals

In most counties, appeals of residential property will require a new appraisal, typically made using the

market approach and supported by the cost approach. Income properties receive new appraisals using

the most appropriate (income, market, cost) method.

Although more closely associated with office time, the appraiser must also be given adequate time

for preparation and testimony at BOPTA hearings, Department of Revenue supervisory or hardship

conferences, Magistrate hearings, and Regular Division Tax Court hearings.

Summary

Proper administration requires that the assessor maintain a sufficient number of skilled staff to conduct

the necessary functions of the assessor’s office. In addition to maintaining adequate staff, the assessor is

required to maintain current procedures and ensure that staff maintains its competency through annual

training. By using the proper administrative procedures and a good organizational structure, a legal and

equitable assessment roll can be achieved.

2-12

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Chapter 3

Records

Assessors have responsibility for locating, identifying, inventorying, and valuing all property in their

counties. The assessor must be able to explain and defend each assessed value. It is essential to maintain

accurate records that show the underlying factors and procedures used.

Office records used by assessors and their staffs include many documents, both in hard copy and

computerized formats. Some of these records include:

• Property transaction records;

• Property description cards (taxlot cards);

• Journal vouchers for tracking account changes;

• Office or counter maps;

• Appraisal maps;

• Sales cards/sales printouts;

• Sales questionnaires;

• Ownership indexes;

• Appraisal inventory cards;

• Confidential real and personal property returns;

• Exemption files/special assessment files;

• Our appraised industrial and centrally assessed property files;

• Real property assessment roll;

• Personal property assessment roll; and

• Administrative records.

Examples and brief descriptions of some types of records used in an assessor’s office begin on the

following page.

3-1

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Property transaction records

Property transaction records include deeds, contracts, and any other instrument that conveys an interest

in real property. These instruments may be documents recorded in the clerk or recorder’s office (in

home–rule counties, the recorder’s office) or they may be provided to the assessor’s office by the taxpayer.

A property transaction document usually contains the name(s) of the grantor(s) and grantee(s), type of

transaction, a description of property, consideration, encumbrances (such as easements, severed mineral

rights, and taxes owed), date of transaction, and the name and address of the party who is to receive the

tax statement. Following is an example of a deed.

3-2

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Example of a deed

The form included here has been reproduced with the permission of Stevens-Ness Law Publishing Co.

No further copying or reproduction in any form is permitted without the express permission of the

Publisher.

3-3

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Property description record

County assessors must set up and maintain a filing system that makes it easy to locate individual

property accounts.

Property description records are commonly referred to as taxlot cards. Information on this record

includes:

• Map number;

• Parcel number;

• Special interest numbers;

• Tax code area number;

• A tie to the parent account;

• Legal description;

• Any taxlots that have been cancelled and combined with another taxlot;

• Gross and net acres;

• Deed references (important for history research purposes);

• Geographic Information System (GIS) coordinates; and

• Exceptions for roads, segregations, and easements.

If taxlot cards are part of an automated system, they need to contain the same information as the manual

taxlot card. Following are two examples of a taxlot card.

3-4

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Example of taxlot card

Twp Rge Sec 1/4 1/16 Parcel Type Num

Map Number Number Spec Int Code

Taxlot Number

Official Record of Descriptions

of Real Property

Union County Assessor's Office

Formerly part of

Description and Record of Change

Acre

Change

Doc

Type

Date of Entry

On This Card

Deed Record Acres Remaining

03S 38E 9 B C 503

1-1

Revised Desrciption PP 8/11/2014

20142040T

0.82

Partition Plat 2014-0011

Parcel 1, 2 & 3

Exc: -0.14 PP 8/11/2014

20142040T

0.68

Parcel 2 (03S38E09BC 525)

Exc: -0.46 PP 8/11/2014

20142040T

0.22

Parcel 3 (03S38E09BC 526)

LLA from 03S 38E 9BC Parcel 526 0.25 SWD 1/21/2016 20152194 0.47

Also: (FTLPO)

BAAP on the W ROW li of Twenty-First Street, sd pt being the NE cor

of Par 3 of PP 20140011T.

Th N89°36'18"W 201.26’ alg the N li of sd Par 3, to the NW cor of sd

Parcel 3,

Th S0°19'20"W 88.58’alg the W li of sd Par 3;

Th S89°31'14"E 100.66’ to the E li of sd Par 3;

Th S0°19'01"W 28.64’ alg said E li of sd Par 3 to the SW cor of Par 1 of

sd PP;

Th S89°31'14"E 100.65’ alg the S li of sd Par 1 to the E li of sd Par 1,

Th N0°18'16"E 117.52’ alg sd W ROW li to the POB.

3-5

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Example of taxlot card

Twp Rge Sec 1/4 1/16 Parcel Type Num

Map Number Number Spec Int Code

Taxlot Number

Official Record of Descriptions

of Real Property

Union County Assessor's Office

Formerly part of 03S38E09BC 503

Description and Record of Change

Acre

Change

Doc

Type

Date of Entry

On This Card

Deed Record Acres Remaining

03S 38E 9 B C 526

5-3

Partition Plat 2014-0011 PP 8/11/2014

20142040T

0.46

Parcel 3

LLA to 03S38E09BC Parcel 503 -0.25 SWD 1/21/2016 20152194 0.21

Exc: (FTLPO)

BAAP on the W ROW li of Twenty-First Street, sd pt being the NE cor

of Par 3 of PP 20140011T.

Th N89°36'18"W 201.26’ alg the N li of sd Par 3, to the NW cor of sd

Parcel 3,

Th S0°19'20"W 88.58’alg the W li of sd Par 3;

Th S89°31'14"E 100.66’ to the E li of sd Par 3;

Th S0°19'01"W 28.64’ alg said E li of sd Par 3 to the SW cor of Par 1 of

sd PP;

Th S89°31'14"E 100.65’ alg the S li of sd Par 1 to the E li of sd Par 1,

Th N0°18'16"E 117.52’ alg sd W ROW li to the POB.

3-6

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Journal vouchers

A journal voucher assures that the various steps necessary in assessment and taxation have been

completed. The journal voucher form can either be hard copy or computerized. If the voucher is

computer-generated, all information is entered directly into the system, thus eliminating the need for a

hard copy. A journal voucher system that uses sequential numbering and is filed numerically makes it

easy to locate vouchers. Include all information needed to update the assessment roll:

• Grantor;

• Grantee;

• Affected taxlot(s);

• New account number;

• Deleted accounts;

• Computer reference number;

• Old and new acreage;

• Reason for change;

• Deed reference, including type of deed and date of deed; and

• Check–off list associated with office flow to assure all required functions have been completed.

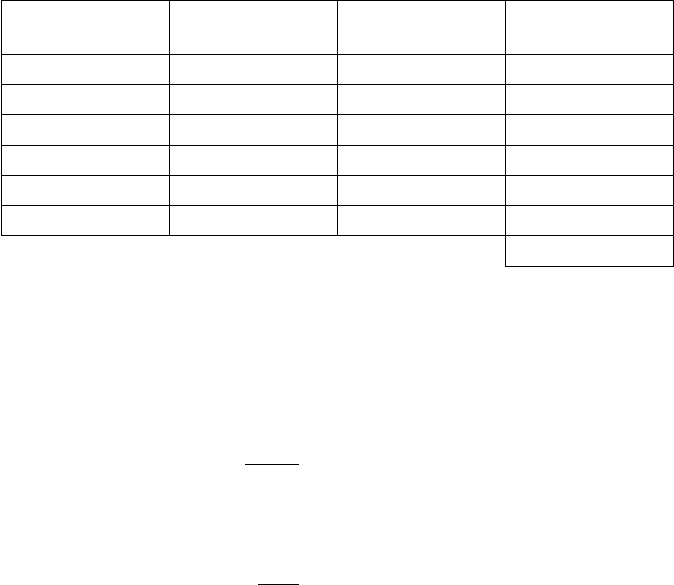

Following is an example of a journal voucher.

3-7

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Reference # 5493

Maintenance ID # 4932

ASSESSOR'S JOURNAL VOUCHER

Union County

Assessment Years Affected

Check when completed and ready to file

PRESENT ACCOUNT NEW ACCOUNT

Code Code

Account No Name of Owner Account No Name of Owner

Class Class

Land Land

Improv Improv

Exemp Exemp

TOTAL TOTAL

PRESENT RECORD NEW RECORD NEW ACCOUNT CHANGES TO ROLL

Acres Value Acres Value Acres Value Acres Val Inc Val Decl

Reason for Change

Changes Needed

Completed

(initial)

1. 1.

2. 2.

3. 3.

4. 4.

5. 5.

6. 6.

7. 7.

8. 8.

9. 9.

10. 10.

11. 11.

12. 12.

13. 13.

14. 14.

15. 15.

16. 16.

17. 17.

18. 18.

19. 19.

Name Change

Acreage Change

Value Change

Segregation

Consolidation

Code Change

Omitted Property

Double Assessment

Clerical Error

Cancelled

Examination Change

Per Prop Value Change

Per Prop New Account

R/W

New Map

Non-Contiguous Parcel

Lot Line Adjustment

Subdivision/Partition Plat

Other

Counter Map

Map Tracing

Taxlot Card

Fly Sheet

Appraisal Map

Soil Class Map

Index Card Filed

Sales Data Card

Appraisal Envelope (Value)

Copy to Appraisal Section

Copy to Collector

New Forms

New Tax Roll and Statement to

Collector

Assessment Roll

Computer

Detail

PERSONAL PROPERTY

Class Present Value Revised Value

Change to Roll

Inc -(Decl)

1. Other Mach

and Equip

2. Furn Equip

in Coml Use

TOTAL

TAX COLLECTOR'S OFFICE

Collector's JV No

Tax Roll Corrected

Statement Corrected

Remarks

INSTRUMENT RECORD

No.

Type

Sale Price

Date

Prepared By Date Confirmed

Telephone Mail/Email Counter

150-303-034 (Revised 1-2014) County Form, Oregon Department of Revenue

SH

SH

1-1 1-1

03S 38E 9BC 526 Hunt, L Wavel & Judy A

LLA to parcel 503 of 0.25 acres.

0.46 0.21 0.47

03S 38E 9BC 503 Pfaff, Wade E & Stephanie C

LLA from parcel 526 of 0.25 acres.

MID# 4932

CS 036-2015

20152194 7/10/2015

SWD

$225,000.00

Sally Hood 1/21/2016

3-8

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Sales data records

Use sales data records to analyze market data for appraisals (ORS 308.232 and ORS 308.233), to measure

results against appraisal standards (ORS 308.234 and OAR 150-308-0380), and for the annual sales ratio

study (ORS 309.200 and OAR 150-309-0250). Sales information is taken from recorded instruments, such

as deeds and contracts, and documentation like Multiple Listing Service data. This process is known as

sales take-off.

The office of the clerk or recorder and the cartography section of the assessor’s office identify the

properties that have transferred or conveyed whole or partial ownership. In several counties, our

cartography section performs the mapping duties under contract with the county.

Written procedures with specific timelines can be developed to show the process of sales information

moving quickly from the clerk’s office through the cartography section and on to the data analyst. The

data analyst needs to ensure that the sales collection, confirmation, and qualification process is current.

Following are examples of computerized sales data records.

3-9

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Examples of property transfer screens

3-10

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

3-11

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Chapter 4

Oregon Cadastral Map System

Purpose

The primary purpose of the Oregon Cadastral Map System is to discover, identify, and inventory all real

property within the state of Oregon.

A joint effort of several counties and what was then the State Tax Commission first began to develop

standards for the Oregon Cadastral Map System in 1952. The state standards continue to evolve to keep

pace with new laws and new technology.

New technology in recent years includes the Computer Assisted Mapping System (CAMS) and

Geographic Information Systems (GIS). These systems link appraisal records to the corresponding parcel

on the map.

The Oregon Map Project (ORMAP) is the latest mapping concept. Its ongoing purpose is to develop a

statewide property tax parcel base map that is digital and continually maintained. ORMAP will support

a variety of GIS applications and has improved the administration of the property tax system.

The Oregon Cadastral Map System is based on the U.S. Rectangular Survey System (USRSS). The national

system uses township, range, and section references. Oregon is divided into four quadrants of the USRSS.

Townships are divided into two north and south quadrants. Townships lying north of the Oregon Base

Line are North Townships and those lying south of the base line are South Townships. Ranges are also

divided into two east and west quadrants. West Ranges are west of the Willamette Meridian and East

Ranges are east of that meridian.

On the next page is a map showing the Willamette Meridian and Oregon Base Line.

4-1

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Map of base line and meridian

4-2

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Township map

Townships are approximately six miles square and are divided into 36 sections. Each section is

approximately one mile square and contains approximately 640 acres.

4-3

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Sections are divided into four one-quarter sections, each approximately one-half mile square and

containing approximately 160 acres. Quarter sections are labeled according to their location within the

section:

NE 1/4 = A NW 1/4 = B

SW 1/4 = C SE 1/4 = D

4-4

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Each quarter section is divided into fourths, or quarter-quarter sections. Each quarter-quarter section

is approximately one-quarter mile square and contains approximately 40 acres. The quarter-quarter

sections are labeled according to location within the quarter section:

NE 1/4 NE 1/4 = AA NW 1/4 NE 1/4 = AB

SW 1/4 NE 1/4 = AC SE 1/4 NE 1/4 = AD

4-5

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

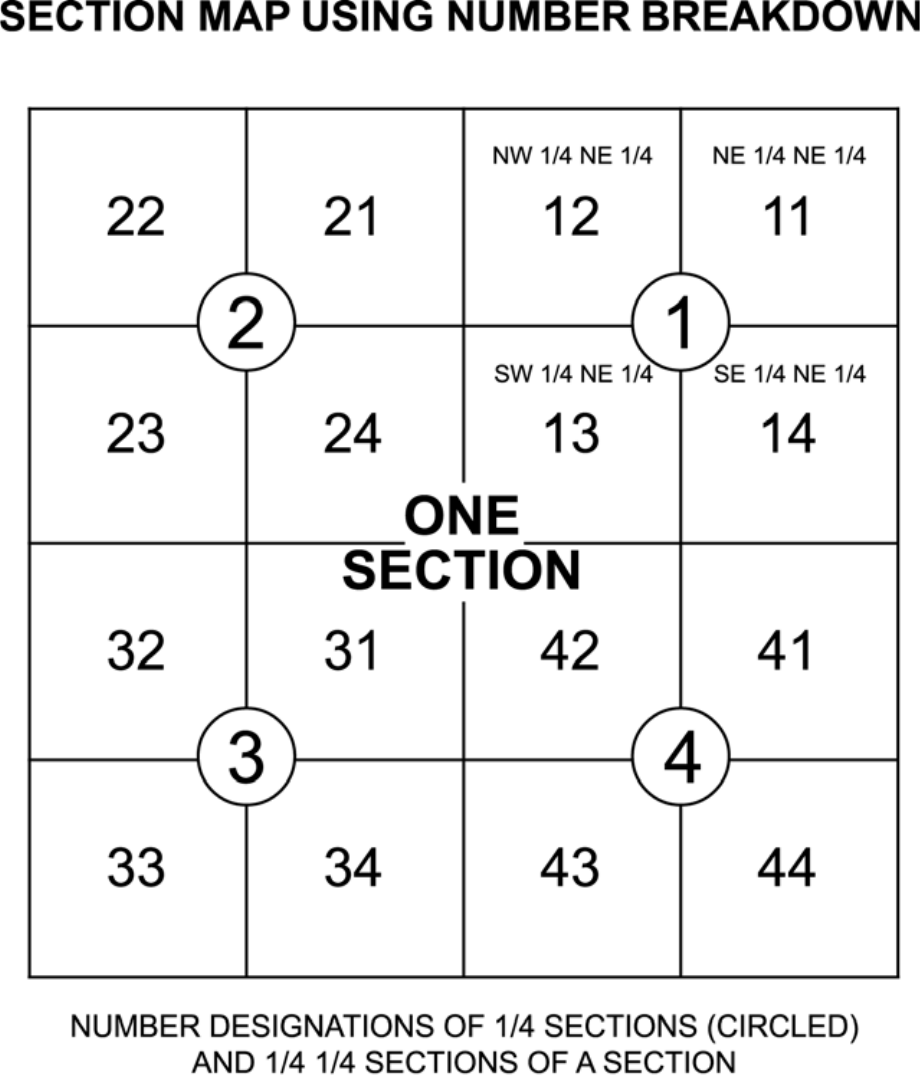

In some counties, computers are not able to integrate alpha characters with numeric characters. In these

counties, the maps use a numeric designation instead of the more common letter designation. Sections

are divided in the same manner. Numbered designations are assigned in the following manner:

Quarter sections

NE 1/4 = 1 NW 1/4 = 2

SW 1/4 = 3 SE 1/4 = 4

Quarter-quarter sections

NE 1/4 NE 1/4

= 11

NW 1/4 NE 1/4

= 12

SW 1/4 NE 1/4

= 13

SE 1/4 NE 1/4

= 14

4-6

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

4-7

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Standard map number

The Oregon Cadastral Map System contains four standard scale maps:

1 inch = 2,000 feet Township map

1 inch = 400 feet Section map

1 inch = 200 feet Quarter section map

1 inch = 100 feet Quarter-Quarter section map

A map’s scale is determined by the number of parcels in the map area, the amount of detailed

information that has to be shown, and an estimate of how much development is expected in the area.

Cadastral maps developed for assessment and taxation are an appraisal tool. They must be constructed at

a scale large enough to show any and all information the appraiser will need when in the field.

The standard cadastral map number is based on the national USRSS system—township, range, and

section. The map number is derived from the map scale. The following examples show map numbers and

their relationship with the scale of the map. We will use Township 11 South, Range 5 West, Section 36.

Map scale Map number

Township Range Section Quarter Quarter-Quarter

1" = 2,000' 11 5

1" = 400' 11 5 36

1" = 200' 11 5 36 A

1" = 100' 11 5 36 A B

The Oregon Cadastral Map System also employs special scale maps. These maps are used to show detail

that can’t be shown on a standard cadastral map. Some of the uses of special scale maps are:

1" = 800' Mining claims (Detail map)

1" = 20' through 1" = 50' Condominiums (Supplemental map)

1" = 20' through 1" = 50' Planned communities (Detail map)

This general explanation of map numbers doesn’t address unique cases such as half townships, three-

quarter ranges, or oversized sections. For explanation of these, see Volume 1, “Concepts and Standards,”

of the Oregon Cadastral Map System.

Standard taxlot number

The standard taxlot number in the Oregon Cadastral Map System is a combination of:

• Map number;

• Parcel number or unit ownership number;

• Special interest number, if applicable; and

• Code number.

The unique property identification number used in the Oregon Cadastral Map System is called a

parcel number. The parcel number is referred to as a “two–zero” number. The numbers are assigned in

numerical order by hundreds. They begin with 100 and proceed in order, such as: 100, 200, 300, 400.

The two–zero number provides an orderly expansion of the parcel number for future segregation: 101,

102, 103, 104, up through 198. It also provides a direct link from the segregation back to the parent account

(or the account it was created from). The 199 number is reserved for omitted property.

A parcel, as defined for assessment and taxation, is a contiguous area of land that is described in a

single description by a closed traverse. The definition of parcel also provides for describing it as one of

a number of lots, blocks, sections, or tracts in a subdivision or section that is separately owned and that

4-8

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

can be separately conveyed. When a parcel number is canceled, it can’t be reused. If parcel numbers are

reused, the previous history is destroyed and research becomes almost impossible.

Code number

The code number used in the standard taxlot number represents a unique combination of taxing districts

that levy, or could levy, a tax on a particular parcel of property. This unique combination of taxing

district levies determines the cost per thousand dollars of assessed value. A taxlot may lie in more than

one tax code, called a split code.

Special interest number

Special interest numbers alert the map user that a particular parcel has something unusual about it. The

special interest number always contains a letter designation followed by a number. The special interest

designations are:

A Improvements only.

F Air space only—above a given elevation.

M Mineral rights—assessed and taxed only if actively being mined as of the assessment date.

S Subsurface ownership.

U Undivided interests.

The number following the special interest letter refers to the number of special interests on a particular

parcel. For example, if you have an airport with a parcel number of 100, and four separately owned

hangars built on the airport property, you would assign improvement-only numbers to the hangars. The

map would show the following numbers:

100

100 A01

100 A02

100 A03

100 A04

A complete taxlot number containing a special interest number is shown as:

2N 4 23AA 100A01 7-02

Township Range Section 1/4 1/4 Parcel Special interest Code no.

2N 4 23 A A 100 A01 7–02

Note that any parcel with an undivided interest will contain a minimum of two special interest numbers;

such as 100 U01, 100 U02.

4-9

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

A typical cadastral map available for appraisal purposes looks like:

Atypicalcadastralmapavailableforappraisalpurposes:

Condominiums

Condominiums are assigned a unique parcel number. This number alerts the appraiser to refer to the

condominium’s recorded plat for the specification of each unit, the dedication and declaration, and the

restrictive covenants that apply to individual condominiums. The parcel numbering for a condominium

begins with 90000.

All condominiums have general common elements owned by all unit owners. General common elements

are not assessed directly. However, they are assigned a value and that value is divided proportionately

among the interest of the unit owners.

An important part of the general common elements is the common area—the land and improvements

that are apart from the unit itself (swimming pool, lawns, recreation rooms, etc.). Although the common

areas are not assessed separately, they must be assigned a taxlot number. That number is composed of the

map number and the four-zero base number of the condominium, called the common area number.

Example: 27 13 36AB 90000

4-10

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

If there is more than one condominium complex on a map, the common area numbers would be:

Examples: 27 13 36AB 80000 (2nd condominium)

27 13 36AB 70000 (3rd condominium)

Unit numbers are assigned to each unit. Each unit in the first condominium on a map would be

numbered consecutively beginning with 90001. If there were 15 units in this condominium, the numbers

would be 90001 through 90015.

In addition to general common elements, many condominiums have limited common elements. Items

limited to unit ownership—such as patios, decks, moorage slip, and aircraft hangers—are limited

common elements.

Planned communities

A planned community is a subdivision that includes a common area and a homeowners’ association

that is responsible for the maintenance and operation of the common area. Owners of individual lots, by

virtue of their ownership, automatically are members of the homeowners’ association.

Each lot in a planned community has a separate parcel number. Each lot must be separately taxed

and assessed. The common properties are taxlotted separately, but under ORS 94.728, are not assessed

separately. The exception is when the declarant alone is liable for payment of taxes on any portion of the

common property of a planned community in which the declarant has reserved the right to develop the

property into additional lots.

4-11

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Chapter 5

Fundamental Appraisal Concepts

Appraising isn’t an exact science. There are no known tables, formulas, or mathematical calculations

that will yield an indisputable estimate of market value. The appraiser must base an opinion of value

upon the ever-changing relationship between human desires and a commodity. Fundamental appraisal

methods enable the appraiser to arrive at an estimate of value that is logical and supportable. Familiarity

with fundamental appraisal theory helps the appraiser understand the importance of factors affecting

buyers and sellers.

The final product of any appraisal is an estimate of value. There are many definitions of value and types

of value. Oregon Revised Statutes, ORS 308.232 and ORS 308.205, provide that the final product of an

assessment appraisal is RMV, or market value. For the definition of RMV refer to the glossary at the end

of this manual.

Appraisal principles

These basic appraisal principles should be considered when valuing property:

Anticipation—Value is the present worth of all the anticipated future benefits to be derived from a

property.

Assemblage—The combining of two or more parcels into one ownership or use.

Balance—Maximum value or profit is achieved or sustained when the agents of production, or the

surrounding land uses, are complementary and in a state of equilibrium. For example, a residential

lot needs complementary land uses like schools, parks, grocery stores, and medical facilities to protect

or maximize its value. Complementary land uses are just as important to commercial property. The

principle of balance also applies to the relationship between land and building.

Change—The principle of change deals with the transitional nature of property. Today’s property

conditions evolved from yesterday and are the basis for forecast of tomorrow’s conditions. Real property,

whether an entire neighborhood or a single property, is constantly changing, at times imperceptibly,

from one condition or stage to another. Stages of change within a neighborhood include the development

or growth stage, static or stability stage, disintegration or decline stage, and revitalization stage. The

principle of change is the law of cause and effect in the market. Change is reflected in the market as

appreciation or depreciation in property value.

Competition. Competition is created by the potential for profit that attracts new sellers and buyers

to a market. Competition among sellers may lead to an oversupply that reduces prices and profits.

Competition among buyers may lead to shortages that increase prices and profits to sellers. Applied to

property, competition means an excess of one type of facility will decrease the value of all such facilities.

Conformity—Value is created, strengthened, or sustained when reasonable homogeneity or similarity

exists. This doesn’t mean monotonous uniformity, but relates to the social and economic forces that create

a complementary mix. Pressure for property to conform may be exerted through zoning or through

deed restrictions on architectural design or size. Conformity works with the principle of progression and

regression. It is also tied to under-improvement and over-improvement concepts.

Consistent use—The principle of consistent use states that the entire property must be valued with a

single use. It is improper to value a property on the basis of one use for the land and another use for the

improvements. This principle is especially important to remember when valuing a property in transition

from one use to another.

5-1

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

Contribution—The principle of contribution states that the value of a component of property depends

upon its contribution to the whole. In other words, the cost of the component doesn’t necessarily equal

the value that the component adds to the property. For example, installing a gold faucet in a low quality

house won’t add as much value to the property as the cost incurred.

Externalities—Externalities are influences from outside the property that affect the value. An appraiser

shouldn’t assume externalities exist. Market analysis is necessary to determine whether external

conditions are affecting the property’s value. Externalities may refer to the use or physical attributes of

properties located near the subject property or to the economic conditions that affect the market in which

the subject property competes. For example, construction of a sewage treatment plant near the subject

property may have a negative impact on value.

Increasing and decreasing returns—Increasing the amount of agents in production produces a greater

net return to the property up to a point (point of diminishing returns). Once the point of diminishing

returns is reached, successive investment increments will decrease their net benefit to the property. This

principle helps the appraiser compare alternative use patterns and intensities of use to establish the

highest and best use of the property.

Plottage—An increment of value that results when two or more sites are assembled under a single

ownership to produce greater utility.

Progression—The concept that the value of an inferior property is enhanced by proximity to a superior

property.

Regression—The concept that the value of a superior property is adversely affected by its association

with an inferior property.

Substitution—A property’s value is typically based on the value of an equally desirable substitute

property. People tend to pay no more for a property than they would pay to acquire substitute property

of equivalent utility, assuming there are no costly delays. The principle also recognizes that the substitute

property with the lowest price will attract the greatest demand and widest distribution in the market.

The principle of substitution is fundamental to all approaches to value. The cost approach is influenced

by this principle, in that a purchaser may acquire a similar site and construct a building of like utility.

The sales comparison approach relates by substituting one property for a comparable property. The

income approach specifically relates to the option of substituting one income stream for another. Income-

producing properties can be substituted for different investments as they relate to risk and return.

Supply and demand—The utility of real property creates demand, which is desire for possession.

Demand is effective when supported by purchasing power. Value increases if supply of real property is

reduced by demand, resulting in scarcity. The value of property depends upon the demand for that type

of property and varies directly, but not necessarily proportionally, to the supply available within the

limits of the available purchasing power.

Surplus productivity—The net income that remains after the cost of capital, labor, and management has

been paid.

Highest and best use

Highest and best use is the basic premise of RMV. Highest and best use analysis is an integral part of the

appraisal process. It is based on the accepted economic assumption that people involved in the real estate

market want to receive the maximum benefit of either the land or the improved property, whichever

produces the greatest overall investment return.

Highest and best use defined:

The reasonably probable use of property that results in the highest

value as of the date of the appraisal.

5-2

150-303-415 (Rev. 05-17) Appraisal Methods for Real Property

To reconcile a property’s highest and best use, the appraiser must answer these four questions in order to

determine whether a use is reasonably probable:

• Physically possible—suited to the size, shape, and terrain of the parcel?

• Legally permissible—conforming to zoning, building codes, private restrictions, environmental

regulations, and other governmental controls?

• Financially feasible—resulting in a positive net return to the property?

• Maximally productive—producing the highest rate of return or highest value for the property?

The proposed use that answers all of these questions positively is the subject property’s highest and best use.

Land value is always based on the land’s highest and best use as though vacant, even if the site is