Shared property services in

the public sector: a future of

collaboration?

Author:

Brian Thompson

Director, realestateworks Ltd

brian@realestateworks.co.uk

RICS Lead:

Jon Bowey

Associate Director, Property Professional Groups

jbowey@rics.org

Contributors

RICS Public Sector Group

Association of Chief Estates Surveyors

Crown copyright material is reproduced under the Open

Government Licence v3.0 for public sector information

Published by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS)

RICS, Parliament Square, London SW1P 3AD

www.rics.org

The views expressed by the authors are not necessarily those of RICS nor any body

connected with RICS. Neither the authors, nor RICS accept any liability arising from

the use of this publication.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any

information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the

publisher.

Copyright RICS 2017

rics.org/insight

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

1

Report for RICS

rics.org/insight

Content s

Executive summary ...................................................................... 4

1.0 Introduction ........................................................................... 5

2.0 Evolution of trading and sharing ........................................... 6

2.1 Legislation ................................................................. 6

2.2 Other government programmes .............................. 7

2.3 Austerity .................................................................... 8

2.4 Evidence of change ................................................... 9

3.0 The questionnaire .................................................................. 10

3.1 Respondents ............................................................. 10

3.2 Questions on shared property services .................. 11

3.3 Statements ............................................................... 12

4.0 Case studies ........................................................................... 23

4.1 Richmond and Wandsworth Councils ...................... 23

4.2 Place Partnership ..................................................... 24

4.3 A five-council partnership ....................................... 25

4.4 Essentia ..................................................................... 25

5.0 Conclusions ........................................................................... 26

6.0 Acknowledgments ................................................................. 27

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

2

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Figures

Figure 1 Geography - regional distribution of responses ... 10

Figure 2 Sector distribution of responses ........................... 10

Figure 3 Awareness of shared property services ................ 11

Figure 4 Participation in shared property services ............ 11

Figure 5 Public sector ethos ................................................. 12

Figure 6 Better value for money ........................................... 13

Figure 7 Understanding issues ............................................. 14

Figure 8 Pooling resources ................................................... 15

Figure 9 Costly and time consuming .................................... 16

Figure 10 Commerciality ......................................................... 17

Figure 11 Rise in popularity .................................................... 17

Figure 12 Resistance to collaboration ....................................18

Figure 13 Selective collaboration ........................................... 19

Figure 14 Appetite to buy or sell ............................................. 20

Figure 15 Availability of resources ......................................... 20

Figure 16 Local knowledge ..................................................... 21

Figure 17 Preparedness to sell services ................................ 21

Figure 18 Appetite to learn more ............................................ 22

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

3

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

rics.org/insight

rics.org/insight

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

4

Executive summary

The days when public sector service providers worked

alone or, worse, in competition with other providers, are

thankfully no more. Whether this is because of a genuine

collaborative spirit or because they recognise their survival

depends on working with partners, the result is that

shared services have increased across the public sector.

New legislative freedoms are also partly responsible

for the rise of this model of service delivery, which

encompasses joint ventures and corporate entities.

Shared property services are now trying to catch up,

spurred on by government programmes like One Public

Estate (see section 2.2.2). At one extreme, shared

property services can involve a public sector body

supplying a resource to another on an ad hoc basis (and

often for free), which is both informal and unstructured.

But at the other end of the scale, a shared property

services arrangement might involve creating an entirely

new company to serve public sector shareholders and,

potentially, the wider market. There are of course many

variations between these two extremes.

Research

RICS commissioned a research project to understand

the pace of change of shared property services in the

public sector. To gather opinions, they published an

online questionnaire that the Association of Chief Estates

Surveyors and Property Managers in the Public Sector

(ACES) then promoted. They also spoke to various

organisations across the public sector with experience of

shared property services.

The key findings are:

• Shared services are already widespread, and we are

likely to see many more develop over time.

• Having a public service ethos, that is being

committed to the value to society that your work

provides rather than being purely motivated by

financial rewards, is an important part of delivering

shared property services, but the distinction between

the public and private sector is becoming blurred.

• It appears there is a market opportunity if working

with public sector partners is seen as providing better

value for money, particularly as public sector partners

are also seen as more likely to understand a buyer’s

issues.

• Although there is some political distaste, sharing

resources might be the best way to make sure the

public sector retains specialist skills.

• Public sector partners can potentially deliver a wide

range of property services.

• There is a clear appetite within the sector to learn

more about shared property service models – this is

even evident among people who have either bought

or sold property services.

The report also raises several points that anyone thinking

about sharing resources needs to consider:

• An exit strategy, or at least a plan to handle the

partnership being dissolved, should be put in place at

the start (even though it might be unpleasant).

• Those who provide services to others might need

to change their culture. They may need to move

away from being public servants towards becoming

commercial professional services providers.

• An effective resource-sharing strategy among

partners could be a catalyst to recruit new property

professionals into the public sector.

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

5

1.0 Introduction

There are many examples of the public sector coming

together to share services because it wants or has to.

Back office functions have traditionally been seen as an

area for immediate positive results for integration, but this

has typically been restricted to HR, legal and financial

services.

Some might argue the importance of local knowledge

means that property services do not readily lend

themselves to integration or sharing across boundaries.

However, this might just be an excuse to try to keep their

independence.

Research gap

Property services, along with frontline services, are now

firmly in the spotlight for sharing or integration in some

form. But there does not appear to be much research into

how much these services are already shared or what the

barriers and outcomes are. The purpose of this research,

carried out with ACES, is to gauge the opinions of those

operating in the market.

Research methodology

RICS published a short online questionnaire on their

website in March and April 2017. They also carried out

face-to-face discussions and phone interviews with

people from several shared services organisations. The

findings from these are shown in the case studies in

section 4.0.

The report begins with commentary on the legislative

and policy framework surrounding the creation of trading

entities and the sharing of resources.

rics.org/insight

rics.org/insight

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

6

2.0 Evolution of trading and sharing

The following commentary puts the findings of the

research into context. It details the frameworks the

public sector operates in that involve trading and sharing

resources, and also looks at the drip feeding of new

programmes and initiatives that encourage collaboration in

one form or another.

For decades, the public sector has traded services to

fellow organisations. The difference now is the pace and

urgency with which some organisations are building

partnerships to share services. Sharing resources is seen

by some as a must to make sure organisations can survive

and improved service delivery is a welcome by-product.

2.1 Legislation

2.1.1 The Local Government Act 1972

Section 111 of the Local Government Act 1972 gave

local authorities the power to do anything ‘which is

calculated to facilitate, or is conducive or incidental to, the

discharge of any of their functions’. Section 112 enables

local authorities to appoint officers to carry out their own

functions as well as any performed for another local

authority. And section 113 allows local authorities to make

agreements with other authorities to place its officers

at the disposal of the other authority, subject to certain

conditions.

2.1.2 The Local Authorities (Goods and

Services) Act 1970

Section 1 of the Local Authorities (Goods and Services)

Act 1970 allows a local authority to make an agreement

with another to provide them with goods and services.

This could include administrative, professional or technical

services.

2.1.3 The Local Government Act 2000

Part 1 of the Local Government Act 2000 gave principal

authorities (county councils, district councils, London

boroughs and unitary authorities) in England and

Wales the power to promote the economic, social and

environmental wellbeing of their areas. Section 20 of the

Local Government in Scotland Act 2003 introduced a

similar power in Scotland.

This helped local authorities build partnerships with

commercial, private and third sector partners, as well

as other public organisations. In theory at least, it

also allowed them to move from a naturally cautious

approach towards a more innovative one involving joint

action. However, evidence suggests they only used it

occasionally, partly because of the complex legal position.

The wellbeing power has now been repealed in England,

although it is still in force in Wales.

In 2008, the Department for Communities and Local

Government produced a report called Practical use of the

well-being power. The report concluded that:

‘…councils are not fully aware of the opportunities

provided by the power to improve well-being

introduced in 2000 to give local authorities the

statutory powers necessary to allow them to play

their full part in improving the quality of life for

local people.’

Under the Local Government Act 2000, local authorities

also became responsible for putting together a sustainable

community strategy. This strategy sets out their long-

term vision for the economic, social and environmental

wellbeing of their areas. To do this they were encouraged

to form a local strategic partnership to help find and work

with other local service providers. They would then work

together on the strategy and agree ways to put it in place

using the new wellbeing powers (among others).

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

7

2.1.4 The Local Government Act 2003

The Local Government Act 2003 introduced a new general

power for local authorities to charge for discretionary

services. This included services they chose to provide

under the wellbeing power.

2.1.5 The Localism Act 2011

Part 1 of the Localism Act 2011 gave a general power

of competence to local authorities in England, giving

them another legal route to provide shared services.

It determined that local authorities that want to deliver

shared services by ‘trading for a commercial purpose’ (in

other words for profit), must do that through a separate

company.

This does not extend to Wales, Scotland or Northern

Ireland. Local authorities that want to use it to help with

joint working across public sector partners might run into

problems, as currently it does not apply to the NHS or to

police services.

2.2 Other government

2.2 programmes

While there have been other government programmes that

have resulted in services being shared, these were more in

the form of incentives rather than enablers.

2.2.1 Devolution deals

In 2015 and 2016, the government and local areas agreed

a number of devolution deals, mainly involving new or

planned combined authorities. Several deals included a

commitment to share services between local authorities.

For example, Greater Manchester’s devolution deal

included commitments to redesign children’s services

across the ten Greater Manchester boroughs.

2.2.2 One Public Estate

One Public Estate is a national programme jointly run by

the Government Property Unit and the Local Government

Association. The first phase was launched in 2013, and

it is now on its sixth. Over 75 per cent of local authorities

take part in it along with wider public sector partners. Its

objective is to build collaboration on asset management to

achieve various outcomes, and it allows the public sector

bodies taking part to choose the paths they want to follow.

For example, one path might involve sharing property

resources, while another could mean setting up a new

combined property vehicle.

It would be unusual today if newly created groups of public

bodies given funding by One Public Estate did not at least

look at the opportunities available to share resources.

Setting up companies to trade

commercially

Section 1(1) of the Localism Act 2011 states that

‘a local authority has power to do anything that

individuals generally may do’. As mentioned above,

section 3 says that although they can undertake

commercial activities, they must do it through a

company (but they can’t sell services they have

a statutory requirement to provide). Some local

authorities have used this provision to sell services,

which implies competing on the open market with

other commercial providers.

In 2013, the Local Government Association published

a The General Power of Competence: Empowering

Councils to Make a Difference on the new power

confirming it was a step in the right direction.

They gave several examples of local authorities’

imaginative use of it, including one that involved

sharing an entire management team across two

authorities:

‘Several councils cited the broader definition

of the General Power compared to the

previous wellbeing powers (where it was

necessary to identify a specific link to the

economic, environmental or social wellbeing

of the area) as providing a more secure legal

basis for entering shared services or similar

arrangements. It had reduced the uncertainty

arising from previous litigation in this area.’

rics.org/insight

rics.org/insight

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

8

2.3 Austerity

A commentary on shared services would not be complete

without mentioning austerity. Recent collaborations

between public bodies at a strategic rather than tactical

level are a direct response to financial challenges. Rather

than cutting services (and facing losing votes), local

politicians have had to work with public sector partners in a

marriage of convenience.

2.3.1 A partnership between three London

boroughs

When the landmark tri-borough partnership of Kensington

and Chelsea, Hammersmith and Fulham, and Westminster

councils was launched, the key aims were to:

• cut the number of middle and senior managers in

combined services by 50 per cent

• reduce the ‘overheads’ on direct services to the public

by 50 per cent and

• make sure that the costs for these overheads and for

middle and senior management would be a smaller

proportion of the total spend in 2014 and 2015 than

they were in 2010 and 2011.

One early indication of the potential benefits of bringing

together these aspects of asset management was the

councils entering into a ten-year total facilities management

contract with Amey in 2013. Significant progress was made

with some £43m saved across the three councils. Then in

2014, Labour regained control of Hammersmith and Fulham

after eight years of Conservative administration. Rather

than scrapping the tri-borough arrangement partnership,

the new leader said he wanted to reform it. However,

three years later, in March 2017, notice was served on

Hammersmith and Fulham council by its ‘partners’. Political

trust appeared to have been lost at the election.

The above scenario shows some of the problems caused

when a shared service agreement unravels, particularly

where resources have been brought together and pared

back, and single systems have been created instead of

independent solutions. The loss of Hammersmith and

Fulham has no doubt been sweetened by the fact that

several other London boroughs signed up to the tri-borough

facilities management framework during 2014 and 2016.

2.3.2 Shared staffing agreements

In 2016, a unique alliance was created between the London

boroughs of Richmond and Wandsworth. Under a shared

staffing arrangement, staff were merged into a single

structure in October of that year. The highly publicised aim

of this was to save up to £10m a year for each authority (see

section 4.1).

This type of arrangement arguably creates new challenges

if the parties later fall out. But current proposals in Dorset

to create two new local authorities from nine existing

ones (amalgamating the county council with districts

and boroughs) should avoid this. The two new enlarged

authorities (if created) will have the ability to establish

entirely new and dedicated organisational structures.

Redrawing the local authority map in response to funding

cuts will create more certainty in the long term, and it

might help to sustain skilled property resources within local

government.

In Scotland, there’s now one police force – Police Scotland

– after eight forces were amalgamated in 2013. In the same

year the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service was created

as a similar number of locally based public sector bodies

disappeared. And in Wales, government reform isn’t far

away. With all local authorities now guaranteed a future due

to the development of the legislative framework described

above, at least in the medium term, it’s expected that

regional working will be established across many local

government services, which could include the sharing of

resources across neighbouring local authorities. The White

Paper on reform launched in 2017 specifically identifies

asset management as a ‘specialist service’ that lends itself

to a regional approach.

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

9

2.4 Evidence of change

It is difficult to quantify the impact of these changes

on whether public sector bodies are now acting more

commercially when collaborating with others. But the

evidence points towards a clear upward trajectory. The

following examples demonstrate the trend.

2.4.1 Commercial Councils, Localis 2015

A survey by the independent think tank Localis of 150 key

local government figures showed that:

• 94 per cent of councils currently share a service with

another council

• 91 per cent use assets (like land) in an entrepreneurial

way and

• 62 per cent run joint ventures with neighbouring

councils, 57 per cent with the private sector and 54 per

cent with the voluntary sector.

Looking forward, Localis concluded that:

‘…entrepreneurial activities make up 6% of total

council budgets at present. In five years’ time, the

weighted average of our respondents indicates that

entrepreneurial endeavours will treble and equate

to a far higher 18% of total council budgets. This

equates to a shift from around £10bn of activity to

£27.4bn by the end of the next parliament.’

2.4.2 Local Government Association shared

2.4.2 services map

For several years the Local Government Association has

used a database to produce a map of shared service

activities in local government across England. In 2015, it

reported that there were 416 shared service arrangements

between councils, with £462m of efficiency savings.

The data for 2017 shows a dramatic increase – there are

now 464 reported examples of shared services with an

estimated £640m of savings for taxpayers. The potential

savings are actually even higher than this, as more than

280 authorities stated that they couldn’t estimate what they

expected to save.

rics.org/insight

rics.org/insight

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

10

3.0 The questionnaire

3.1 Respondents

Between March and April 2017, 43 people responded to RICS’ online questionnaire. The figures below show the

characteristics of the respondents.

Figure 1: Geography - regional distribution of responses

42%

2%

England

Scotland

Wales

Figure 2: Sector distribution of responses

65%

9%

7%

5%

12%

Local government

Health

Emergency

Other public sector

Self-employed

Central government

56%

2%

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

11

3.2 Questions on shared property services

Once the respondent’s main work location and employment were established, they were asked questions to check their

awareness of shared property services.

3.2.1 ‘Are you aware of any shared property services ventures?’

The responses show that a high level of awareness of shared property services exists across the public sector.

91%

9%

Yes

No

Figure 3: Awareness of shared property services

3.2.2 ‘Do you participate or have you participated in a shared property services venture?’

Given the relatively wide definition of shared property services used (from informal arrangements where services are

provided for free or on a cost-recovery basis, to formally constituted entities specifically set up to trade), it might be

surprising that 40 per cent of respondents do not take part in any form of sharing.

Yes

No

60%

40%

Figure 4: Participation in shared property services

rics.org/insight

rics.org/insight

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

12

3.3 Statements

A range of statements was then set out. Respondents were asked to give their view on each one, ranging from ‘Strongly

agree’ to ‘Strongly disagree’.

3.3.1 ‘Resources accessed from partners via a shared service arrangement will possess a

critical public sector ethos’

This proposition was looking to understand whether procuring services from a public sector partner guarantees that

services are coming from those with a public sector ethos. While 72 per cent of respondents agreed with this (without

any definition of what a public sector ethos actually means today), 23 per cent claimed they didn’t know the answer to

the question. Does this indicate that people no longer understand the classical interpretation of the public sector ethos –

working to make a difference rather than just to make a living?

Critics of outsourcing often identify private sector suppliers’ lack of understanding of the public sector and the absence of

a relevant ethos as reasons why it should be resisted. But how different are the drivers behind the two sectors? It is wrong

to claim that public sector employees have a vocation while private sector employees seek profit above all else. But there

is no doubt that a blurring of the sectors has been caused in part by the impact of efficiency and commercialisation on the

public sector – saving costs and making money.

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

Figure 5: Public sector ethos

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

13

3.3.2 ‘Better value for money will be obtained through shared services compared with

employing commercial advisers’

Despite there being no definition given for the term ‘value for money’, 60 per cent of respondents agreed with this

proposition. It is safe to assume that respondents consider the term to include aspects of both price and quality. With 95

per cent of respondents working in the public sector, this might at first glance be a surprising result. On the other hand, it

perhaps reflects the recognised shortage of skills across the sector.

Over a quarter of respondents said they didn’t know the answer to the question. This might have been a pragmatic

response as services potentially available from one public sector partner might be vastly different to those from another. But

rather surprisingly, 73 per cent of those who didn’t know the answer were currently either providing or receiving services

to or from a public sector partner. This could point towards a lack of transparency in agreements, an absence of clear

specifications or poor performance monitoring of the outcomes.

There is no doubt that shared property services arrangements must in future be able to transparently demonstrate value for

money to all parties, otherwise they will remain open to criticism and more susceptible to political influence.

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

Figure 6: Better value for money

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

rics.org/insight

rics.org/insight

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

14

3.3.3 ‘Resources procured from partners are more likely to understand the issues facing the

purchaser’

This statement explores a similar issue to the one on ‘ethos’ (section 3.3.1). While a clear majority agreed with it, 16 per

cent didn’t know and almost 10 per cent said that partners wouldn’t necessarily understand their issues. Interestingly, half

of these respondents were from the emergency services sector, which highlights the perceived importance of partners

understanding your core business. In practice, are some services not sufficiently generic that they can be provided across

sectors – e.g. valuation, rating, building surveying and day-to-day property management?

The issues of whether skills can be transferred across subsectors is explored in more detail in section 3.3.4.

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

Figure 7: Understanding issues

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

15

3.3.4 ‘Through “pooling”, specialist resources can be shared and therefore sustained across

public sector partners’

For many years, the public sector has found it hard to recruit and keep property professionals. There is a lot of anecdotal

evidence pointing to challenges to this across the public sector, supported by hard evidence in research and reports:

• Progress on government estate agency: ‘The Ministry of Defence established a central property function, but found

practical skills shortages.’

• NHS estates: Review of the evidence: ‘The identification of skills shortages in strategic estates management in the

public sector make the need to develop in-house capacity clear. This capacity can be developed but can also be built

by capitalising on available skills and mechanisms for sharing and disseminating expertise.’

• NHS estates: Review of the evidence: ‘One Public Estate is a central initiative, organised on a regional basis.

Stakeholders in local government-led, place-based approaches have capitalised heavily on the wider skills available,

e.g. planning, procurement, housing management.’

• a review of Private Finance Initiative and other projects concluded that public sector organisations (including the NHS)

often do not have the skills to make decisions on complex projects. This can put the public sector at a disadvantage

when negotiating with the private sector, and jeopardise the realisation of benefits. The review also found that the

public sector can lack the contract management skills needed to handle complex issues when they come up.

Against this background, this statement explored the views of respondents on the potential for sharing property services to

enable them to survive.

Almost 80 per cent of respondents agreed that sharing was a way to sustain resources within the public sector. One Public

Estate opens the door for collaboration on many fronts – from assets, through data to the use of services. In fact, the

initiative was the inspiration behind the creation of Place Partnership, a public–public company with a mission to deliver

property-related services to its ‘founding fathers’ and others in the public sector (see section 4.2).

There is an argument for specialisation and the sharing of those specialist resources since each public body simply cannot

afford its own internal resource pool. The nurturing of more specialists capable of successfully walking the corridors of

government in the widest sense of the term, and acting as intelligent clients, can only be a good thing for those seeking a

career path in the public sector.

Perhaps surprisingly, 9 per cent of respondents disagreed with the proposition. One reason for this might relate to the

statement in section 3.3.5.

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

Figure 8: Pooling resources

rics.org/insight

rics.org/insight

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

16

3.3.5 ‘It is costly and time consuming to set up a shared services venture’

Despite an introductory comment stating that shared property services include informal arrangements where services are

provided at no charge by one body to another, 42 per cent of respondents said it was expensive and time consuming to

set up a shared services venture. This might have been because the term ‘venture’ indicated a more formal arrangement.

Of those sharing this view, 44 per cent said they had not taken part in a shared property services venture. This might point

towards institutional bias based on the experience of creating companies or partnerships within the public sector. There is

certainly little publicly available data on the range of costs and timescales that people stepping into this territory might incur.

0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35%

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

Figure 9: Costly and time consuming

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

17

3.3.6 ‘Shared service resources will lack the necessary commerciality’

Respondents delivered a vote of confidence in the commerciality of public sector property professionals: 52 per cent

disagreed with the statement even though very few had taken part in a shared services arrangement. In contrast, 25 per

cent of respondents agreed with it, three quarters having participated in a shared services arrangement.

In the final analysis, the level of commerciality will depend on various factors, including the service specification, the

expectations of the parties, and the contract management processes to make sure you get what you pay for.

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

Figure 10: Commerciality

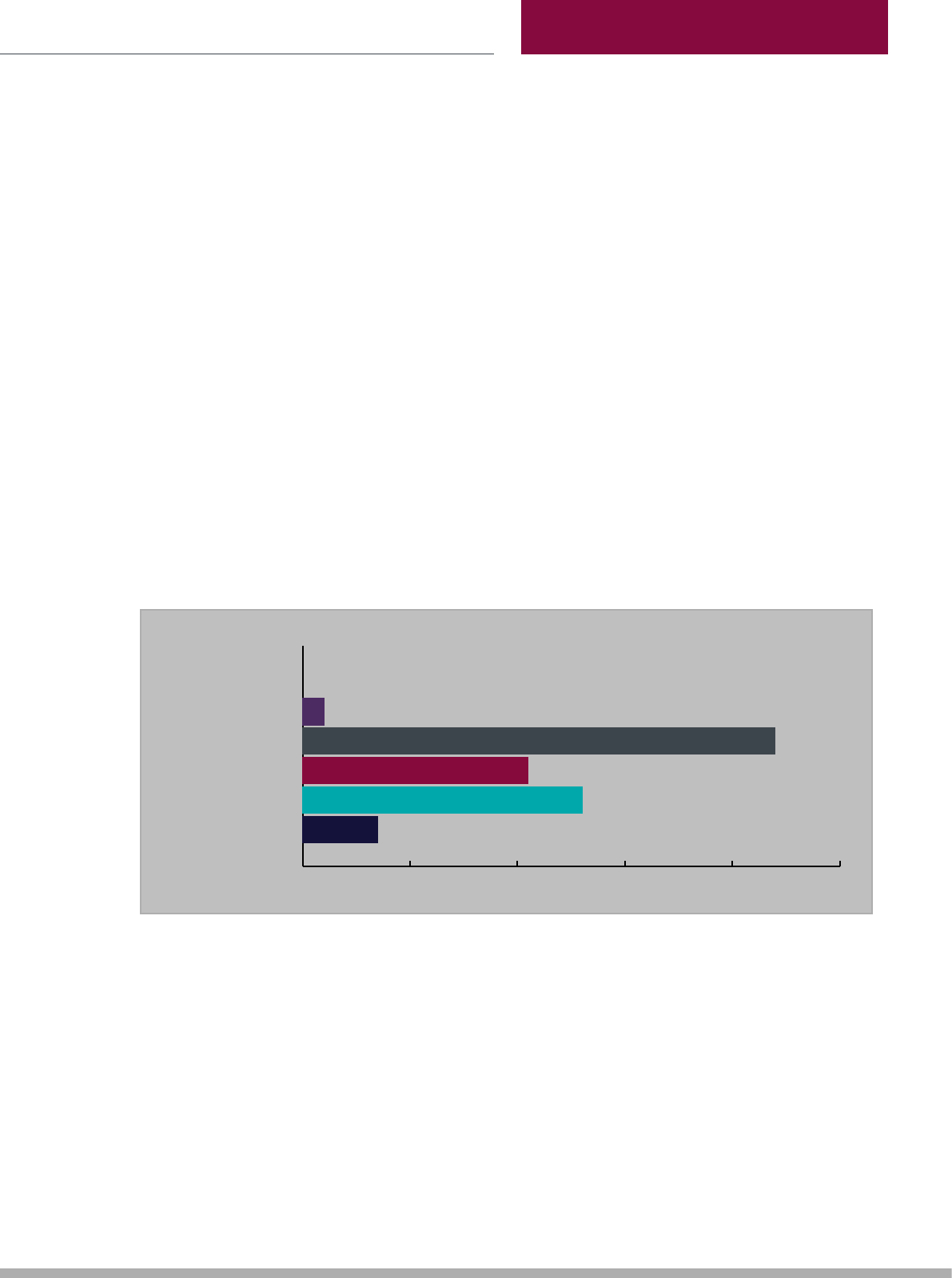

3.3.7 ‘The sharing of property expertise is likely to become more common over time’

There was widespread agreement that the practice of sharing resources will become more common. But 5 per cent of

respondents disagreed with the proposition, even though they had all previously said that sharing provides better value for

money.

In section 2.0, there is a summary of trends and events that have combined to support and encourage parties to join

forces. It is difficult to see this reversing or even slowing down in the next decade – survival for some will rely on meaningful

collaboration.

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

Figure 11: Rise in popularity

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

rics.org/insight

rics.org/insight

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

18

3.3.8 ‘Some public bodies will resist buying from or selling to others for local political reasons’

The day-to-day realities of life in local government are evident in the response to this statement. Most of the respondents

agreed that local politics can, in effect, trump rational decision-making. For example, there is anecdotal evidence that some

local authorities have not applied for One Public Estate funding because the programme originated in a Conservative-

led coalition government. Respondents who agreed with the proposition were from both local government and central

government, the health sector and emergency services.

We can work it out: the human hurdles to collaboration in local government highlights the absence of trust we sometimes

find within organisations we expect to be reliable:

‘As local authorities come under pressure to reduce their spending, collaboration is one way to protect

public services from cuts. The government is encouraging councils to explore opportunities to work with

one another, and with the private and voluntary sectors. But there are some very human obstacles that

prevent collaboration happening as smoothly as it might.’

This content is brought to you by Guardian Professional.

One respondent commented that ‘sovereignty…is a roadblock to general shared property management services’. The

implication is that ceding the management of property to another authority is politically unacceptable – yet many authorities

cede the management of their estates to the private sector. If there are fundamental concerns around political interference

by another authority, or concerns about service quality, continuity and assurance, these can arguably be taken care of

through an appropriate service contract. On the other hand, if the concerns are founded more on emotion than economics,

the tightest contractual arrangement will still not resolve these issues.

A further issue may relate to split loyalties: can a property investment adviser employed by one authority, for example,

provide investment advice to another authority? The answer must be ‘yes’ since no public sector body could successfully

seek exclusivity from its private sector property agent or adviser commissioned to bring forward investment opportunities

or advise on the buying, selling or letting of space. The answer to this potential dilemma is to construct a clear service

specification and confirm at the outset how potential conflicts will be dealt with. In other words, act in a commercial

manner.

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

Figure 12: Resistance to collaboration

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

19

3.3.9 ‘Sharing resources will only work for specific property services’

The field was almost evenly split on this issue. Respondents who agreed or strongly agreed with the proposition were

asked to identify services that could be ‘traded’. While some referred to only one or two specific services, the range

mentioned overall was fairly broad. It covered:

• day-to-day asset management

• valuation

• acquisition and disposals

• condition surveys

• procurement support and

• facilities management.

One respondent with a negative view on the potential for greater sharing commented:

‘A substantial amount of local knowledge is required for a number of property services that is unlikely to

be delivered by a partner.’

While it is true that local knowledge can carry added weight, it can also arguably be gained or learned relatively quickly and

simply. Over time, barriers put up by those with specialist local knowledge will inevitably become easier to overcome.

Echoing earlier comments on political resistance to sharing property services, another respondent said:

‘Sovereignty, or its perception, is a roadblock to general shared property management services.’

This begs a fundamental question about the role of local politicians in asset management – are they owners or custodians?

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

Figure 13: Selective collaboration

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

rics.org/insight

rics.org/insight

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

20

3.3.10 ‘I would consider buying in property services from, or selling services to, public sector

partners’

Without any pre-conditions, this simple two-part statement sought feedback on how many respondents would buy or

sell property services to public sector partners. Over 80 per cent said they would, but somewhat surprisingly, 10 per cent

were undecided – perhaps because they needed to understand the conditions under which they could buy or sell services

before agreeing or disagreeing.

On the face of it, the result indicates there is a clear appetite to trade property services within the public sector.

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80%

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

Figure 14: Appetite to buy or sell

3.3.11 ‘There are insufficient resources at my disposal to deploy across various partners’

Although the appetite to trade services might exist in theory, there are constraints in real life. One of these is the resource

pool available.

While most respondents agreed with the statement, 20 per cent did not. This implies they have resources that could be

used across other public sector partners. Of these, 75 per cent were from local government and all but one confirmed they

would be prepared to trade resources with other partners.

The above findings suggest that there might be a hidden pool of resources available for sharing across the public sector.

But only if the right arrangements are put in place, alongside the political will.

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

Figure 15: Availability of resources

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

21

3.3.12 ‘I need resources with local knowledge and my partner(s) might not be able to provide

this’

For those who already feel that local knowledge is not the overriding factor when procuring resources from a public sector

partner, the findings in relation to the above statement may bring reassurance.

Respondents who disagreed with the statement might actually be disagreeing with the point about needing resources with

local knowledge, or the ability of public sector partners to bring this. Potentially, 40 per cent of respondents do not see

local knowledge as particularly important, or they feel their public sector partners can bring this. Either way, it suggests that

barriers to entry might not be very high.

On the other hand, almost half the respondents said they need resources with local knowledge, and that their partners

might not be able to meet this.

A wider debate about the importance of local knowledge, and how this can be supplied by partners (with or without

external expertise), will help in making choices on resourcing strategies.

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

Figure 16: Local knowledge

3.3.13 ‘I would consider selling services to other partners, subject to internal needs being met

as a priority’

The above statement is very specific on the conditions to be met before surplus resources are sold to other parties. Some

might say, why wouldn’t you consider selling if your needs are met? But 16 per cent of respondents were not able to agree

with the statement. Perhaps the existence of surplus resources might threaten their existence – or maybe the respondents

know the political reality only too well in their organisations.

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80%

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

Figure 17: Preparedness to sell services

0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40%

rics.org/insight

rics.org/insight

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

22

3.3.14 ‘I want to understand more about the alternative structures, cost and benefits for

buying in or selling services’

Little previous research into the items referred to in this statement became evident during the course of producing this

paper. One reason may be that commercial and confidential arrangements have been put in place to govern the buying and

selling of property services. It is acknowledged that some high-profile case studies exist about creating new legal entities.

But what about the less formal approaches to sharing resources covering resource management, costing of services and

quality and performance management?

The vast majority of respondents said they wanted to learn more about sharing services. While 11 per cent of respondents

apparently don’t want to learn more, they all claimed to have experience of buying or selling property services.

Returning to the sample who claimed to have experience buying or selling property services (see section 3.2.2), almost half

wanted to learn more.

No answer

Strongly disagree

Disagree

Don’t know

Agree

Strongly agree

Figure 18: Appetite to learn more

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80%

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

23

4.0 Case studies

4.1 Richmond and Wandsworth

4.1 Councils

Like many local authorities, the two councils were

predicting substantial reductions in funding from two key

sources: Revenue Support Grant and Retained Business

Rates. Between 2015/16 and 2019/20, Richmond Council

assumed that income from these sources would reduce

by 66 per cent while Wandsworth Council was basing

its financial strategy on a reduction amounting to 22 per

cent. In cash terms, the total sum to be secured through

savings and/or additional income streams to recover these

‘losses’ amounted to more than £110m.

With a history of joint working with a range of boroughs

across London, the councils decided to embark on

a ground-breaking proposal through the mechanism

of a Shared Staffing Arrangement (SSA). The SSA

serves a population of approximately 500,000 which,

for comparison, is not far short of the population of

Manchester. Under the SSA, each Borough retains their

independence but services are delivered through a single

staffing structure with a single Chief Executive and one

Service Director for each service area. Preparations

began in 2015 and went live on 1 October 2016. Staff

were transferred into the new SSA with adjustments

made to align terms and conditions to ensure consistency

in relation to issues such as holiday allowances,

performance-related pay, overtime payments and car

allowances.

It was predicted that the creation of single Chief Officer

team would alone save more than £1.6m per annum. This

would make a significant dent on the projected £10m per

annum financial benefit each council would secure from

the operation of the SSA.

Within the Housing and Regeneration Directorate, a

new post of Assistant Director (Property Services) was

created bringing together the property functions of the

two councils, formerly operating very different business

models. Wandsworth Council favoured a multi-disciplinary

in-house team and Richmond Council pursued an

outsourcing model. The extent of overlap and duplication

of roles could have been much more significant were it

not for the divergent approaches to running an estates

function.

With the councils retaining their sovereignty, including key

democratic and governance procedures, the SSA requires

the newly integrated team of 120 or so property, project

management, design and FM professionals to serve two

masters, although some sections within the Property

Services directorate operate trading accounts.

The creation of a single Property Services team created

an initial saving of around £200,000 per annum and it is

expected that there will be further savings by a series of

joint procurements. A range of services are in the process

of being jointly let including cleaning, some hard FM

services, commercial estate management and agency.

Over time, the team could potentially deliver services to

other public bodies but growth into this market does not

feature in the immediate plan for the team.

‘Establishing the SSA and running services for

two boroughs is a huge challenge. However, there

has been considerable mutual learning from staff

who worked for each Borough and adopting best

practice from both. It has also given the service a

critical mass which has created opportunities for

staff development in the broad range of work the

service covers.’

Andy Algar, Assistant Director, Property Services for

Richmond and Wandsworth Councils

rics.org/insight

rics.org/insight

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

24

4.2 Place Partnership

Place Partnership (PP) is a limited company wholly owned

by a number of public sector bodies, namely:

• Hereford & Worcester Fire Authority

• Redditch Borough Council

• Warwickshire Police

• West Mercia Police

• Worcester City Council and

• Worcestershire Borough Council.

It is the first multi-agency asset management company

of its kind in the UK and provides property services to a

core portfolio of some 1,400 assets across four counties.

PP owes its origin to One Public Estate (OPE), the joint

Cabinet Office and the Local Government Association

programme aimed at delivering a range of asset and

service-related outcomes through collaboration across

public sector partners. In the vast majority of instances,

OPE has originated or facilitated tangible projects. In

this instance, a unique entity was created to support

integrated asset management across the partners.

With approximately 180 employees based in Worcester,

PP provides a range of advice and support to its ‘home

team’ of partners in areas such as tactical and strategic

asset management, capital projects, FM, and energy

procurement/management. Since its inception in 2013,

PP has recruited from the public and private sectors

to enhance its capabilities. It has also widened its

customer base to include public sector bodies outside its

geographic boundaries. In time, the strategy for growth

could see PP opening up offices in other parts of the

country. While the Teckal exemption effectively limits

the extent of PP’s growth into the wider market to 20%

of turnover, this leaves ample room for growth into this

market as it currently turns over approximately £25m.

The quantum of external business can increase as the

quantum of the ‘home team’ business increases, which

could include increasing the number of shareholders in the

partnership.

The vision of the partners is embedded in a series of

shared objectives. While a formal common estate strategy

was not documented on day one, this can be seen as

both a strength and a weakness: flexibility on the one

hand, as opposed to challenges in prioritising strategic

objectives in view of the demand for services that the new

joint vehicle has created.

The construct is undoubtedly unique and, being the first

of its kind, it is subject to scrutiny. Some in the public

sector are watching from a distance while others are

actively engaged in discussions to learn from this new

development. Having been awarded ‘Property Newcomer

of the Year’ in the 2017 Property Awards, expectations

have been raised that the new company will deliver

demonstrable performance above and beyond that which

could otherwise have been achieved.

‘Place Partnership is at the very forefront of

facilitating change in public service delivery.

Whilst multi-agency collaboration is undoubtedly

challenging, the benefits can be seen in

the creation of significant capital value and

operational savings, which will realise so many

tangible benefits for the public estate and those

whom it serves.’

Andrew Pollard, Managing Director, Place Partnership

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

25

4.3 A five-council partnership

South Oxfordshire District Council and the Vale of White

Horse District Council have a history of working together.

In 2006, they signed a contract with Capita to outsource

their revenues and benefits services and exchequer

functions. As the contract came close to expiring, the two

councils agreed to extend it by joining forces with other

councils whose contracts with Capita were also about to

expire. Together they created a five-councils partnership

with Hart District Council, Havant Borough Council and

Mendip District Council.

The newly created partnership then signed a nine-year

contract with Capita and Vinci for various services,

including property management. The property

management service was delivered by Arcadis under a

subcontract with Vinci. It covers 40 separate services

including:

• providing a management system

• day-to-day property management

• acquisitions and disposals

• lettings

• development consultancy

• building maintenance

• statutory compliance and

• strategic property advice.

This range of services gives the councils the flexibility

to choose a combination of services that suit their

circumstances

The contract for South Oxfordshire District Council and

Vale of White Horse District Council started in August

2017, and will start for the other councils in late 2017 when

their current contracts with Capita expire. Around ten

estates professionals are expected to transfer to Arcadis,

and it is anticipated they will provide services across

council boundaries from one of two operational hubs. To

help achieve this strategy, the partners can access a wide

pool of resources within Arcadis at agreed rates.

One of the main reasons for creating this five-council

partnership was to give the councils the ability to buy

goods and services together – something that could save

an estimated £50m. And the councils are already looking

at joining forces with another council in the north of

England for valuation services, which will give them even

more buying power.

4.4 Essentia

Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust Hospital

created the Essentia brand and organisation. It was

designed to deliver property and facilities management

services to the Trust with a workforce of 1,800 employees.

In 2013, they created Essentia Trading Limited, a new legal

entity described as Essentia’s commercial arm. It employs

50 people who provide multi-disciplinary consultancy

services to both the Trust and wider market. Its core

services include:

• strategic asset planning

• capital project management

• healthcare planning

• sustainability advice

• IT solutions and

• procurement.

While most of Essentia Trading’s business comes from

clients in the health sector, it has also provided strategic

estates advice to local authorities. This might reflect

the inevitable merging of health and social care service

delivery taking place within communities.

Essentia Trading wins new business in competition with

others, but also through links and relationships that

already exist across the health sector. One of its USPs

is that, unlike commercial competitors, its profits are

recycled back into the Trust.

With a turnover of £6.5m, the business plans to expand

its current national and international customer base. It

has already given specialist healthcare planning advice to

clients in Australia, Qatar and the Republic of Ireland.

When the company was established in 2013, it was made

up of less than ten people. Most of the new recruits over

the last four or so years have come from the private sector.

They generally have track records advising health sector

clients on property asset management and healthcare

planning.

rics.org/insight

rics.org/insight

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

26

5.0 Conclusions

Legislation has paved the way for more imaginative

ventures to be created within the local public sector. This

has undoubtedly had some impact on the pace of change,

but a greater stimulus for change has perhaps been the

‘carrot and stick’ approach:

• provide incentives in the form of more devolved

responsibility in exchange for driving through

efficiencies, or hard cash to test and implement asset

management initiatives like shared property services

or

• squeeze local authorities and others to the point

where collaboration and alliances (or forced

marriages) become the best options.

Whatever the causal factors, the sharing of services is

here to stay.

Results

The survey aimed to understand how strongly RICS

practitioners feel about shared property services. Sharing

can take many forms in practice, as shown by the case

studies in section 4.0, which were put together after face-

to-face meetings and phone interviews.

The dangers of jumping to conclusions on the back of

survey results are well known. This report treads carefully

and identifies the following tentative conclusions:

• Shared services are widespread, and we are likely to

see many more develop over time.

• Public sector ethos is an important factor in delivering

shared property services – but the distinction

between the public and private sectors is becoming

blurred.

• If working with public sector partners is seen as

better value for money, a market opportunity appears

to exist, particularly as public sector partners are seen

as more likely to understand buyers’ issues.

• Despite some political distaste, sharing resources

might be the best way to keep specialist skills within

the public sector.

• The retention or protection of sovereignty can act as

a constraint – but is contracting for the delivery of

day to day property management services to another

public body so different from contracting with a

private sector supplier?

• A wide range of property services is believed to be

potentially deliverable by public sector partners.

• There is a clear appetite within the sector to learn

more about shared property service models. This is

even evident among people who have already bought

or sold property services to partners.

The survey and research undertaken to inform this report

also raise a number of points:

• Exit strategies, or at least a strategy to handle a

partnership being dissolved, should be considered at

the start, even though it might be unpleasant.

• A cultural shift away from public servant towards

commercial professional services provider might

be needed for some. This is deliberately simplistic

but points to the need for a new toolkit including

customer relationship management, competitive

pricing strategies, time recording and quality

management.

• Can an effective resource-sharing strategy among

partners provide a catalyst to recruit new property

professionals into the public sector? If the strategy

is founded on a strong relationship and high level of

trust between partners, the business case could be

very solid. And if the employer is a separate company

shielded from day-to-day political decisions, risks to

prospective employees are reduced.

RICS Insight Paper © 2017

Shared property services in the public sector: a future of collaboration?

27

6.0 Acknowledgments

Thank you to the following for their valuable insights and

contributions to this research:

• Andy Algar (Richmond and Wandsworth Councils)

• Andrew Pollard (Place Partnership)

• Neil O’Connor (Luton Borough Council)

• Peter Beer (5 Council’s Partnership)

• Neil Palmer (Fieldfisher)

• Stephen Edgar (Essentia)

• Dave Pedersen (Suffolk Fire and Rescue)

• Richard Baker (Welsh Government).

rics.org/insight

rics.org/insight

GLOBAL/NOVEMBER 2017/20747/RICS INSIGHTS

Confidence through professional standards

RICS promotes and enforces the highest professional

qualifications and standards in the development and

management of land, real estate, construction and

infrastructure. Our name promises the consistent

delivery of standards – bringing confidence to the

markets we serve.

We accredit 125,000 professionals and any individual or

firm registered with RICS is subject to our quality assurance.

Their expertise covers property, asset valuation and

real estate management; the costing and leadership of

construction projects; the development of infrastructure;

and the management of natural resources, such as mining,

farms and woodland. From environmental assessments

and building controls to negotiating land rights in an

emerging economy; if our professionals are involved the

same standards and ethics apply.

We believe that standards underpin effective markets.

With up to seventy per cent of the world’s wealth bound

up in land and real estate, our sector is vital to economic

development, helping to support stable, sustainable

investment and growth around the globe.

With offices covering the major political and financial centres

of the world, our market presence means we are ideally placed

to influence policy and embed professional standards. We work

at a cross-governmental level, delivering international

standards that will support a safe and vibrant marketplace

in land, real estate, construction and infrastructure, for the

benefit of all.

We are proud of our reputation and we guard it fiercely, so

clients who work with an RICS professional can have confidence

in the quality and ethics of the services they receive.

United Kingdom RICS HQ

Parliament Square, London

SW1P 3AD United Kingdom

Media enquiries

pressoffi[email protected]

Ireland

38 Merrion Square, Dublin 2,

Ireland

t +353 1 644 5500

f +353 1 661 1797

Europe

(excluding UK and Ireland)

Rue Ducale 67,

1000 Brussels,

Belgium

t +32 2 733 10 19

f +32 2 742 97 48

Middle East

Office B303,

The Design House,

Sufouh Gardens,

Dubai, UAE

PO Box 502986

t +971 4 446 2808

Africa

PO Box 3400,

Witkoppen 2068,

South Africa

t +27 11 467 2857

f +27 86 514 0655

Americas

One Grand Central Place,

60 East 42nd Street, Suite #542,

New York 10165 – 2811, USA

t +1 212 847 7400

f +1 212 847 7401

Latin America

Rua Maranhão, 584 – cj 104,

São Paulo – SP, Brasil

t +55 11 2925 0068

Oceania

Suite 1, Level 9,

1 Castlereagh Street,

Sydney NSW 2000. Australia

t +61 2 9216 2333

f +61 2 9232 5591

Greater China (Hong Kong)

3707 Hopewell Centre,

183 Queen’s East

Wanchai, HongKong

t +852 2537 7117

f +852 2537 2756

China (Shanghai)

Room 4707-4708, 47/F

968 Beijing Road West,

Nanjing Road West, Jing’an District,

Shanghai, 200041, China

t +86 21 5243 3090

f +86 21 5243 3091

Japan

Level 14 Hibiya Central Building,

1-2-9 Nishi Shimbashi Minato-Ku,

Tokyo 105-0003, Japan

t +81 3 5532 8813

f +81 3 5532 8814

ASEAN

#27-16, International Plaza,

10 Anson Road,

Singapore 079903

t +65 6812 8188

f +65 6221 9269

South Asia

GF-17. Ground Floor, Block B

Vatika Atrium, Sector 53 Gurgaon,

Haryana 122002, India

t +91 124 459 5400

f +91