94 — Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, Vol. 9, No. 2 • Fall 2018

Keywords: Films, Audiences, Motivations, Attendance, Theaters

Email: e[email protected]

Discovering Audience Motivations Behind Movie Theater Attendance

Emily Flynn

Strategic Communications

Elon University

Submitted in partial fulllment of the requirements in

an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications

Abstract

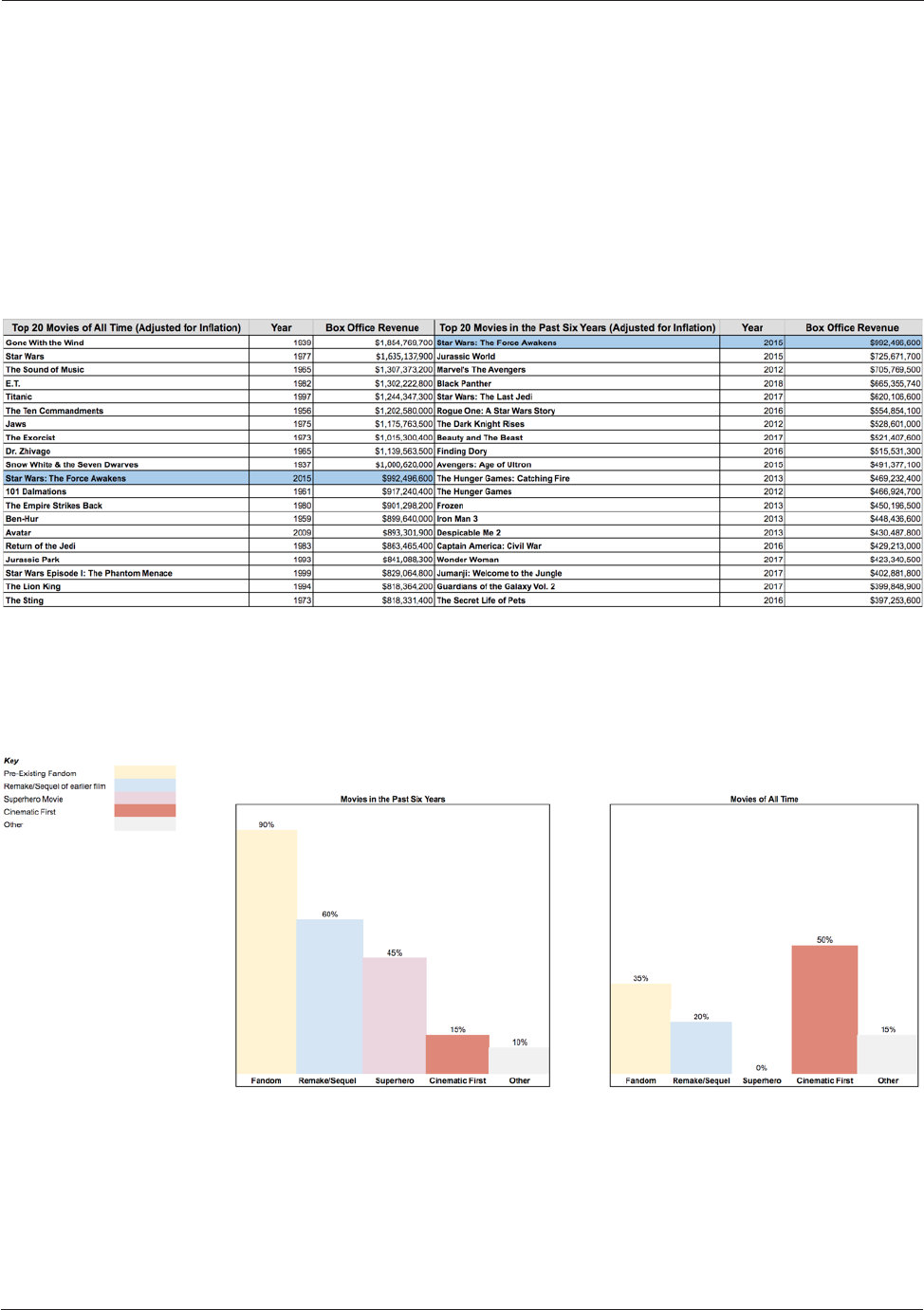

A content analysis tracked the top box ofce lms of the past six years, and the top box ofce lms of all time,

to determine what factors currently draw audiences to movie theaters in comparison to what factors have

drawn audiences in the past. Overall, the study concluded that movie theater attendees are more interested

in watching remakes of old movies, or lms with large fandoms, in order to remain part of an ongoing

conversation. Additionally, evidence suggests viewers tend to enjoy watching lms in community with others,

making movie theaters a prime medium for this type of interaction.

I. Introduction

Brent Lange (2017), Senior Film and Media Editor for Variety, noted that despite the rich and

successful history of movie theaters, “there is mounting anxiety among theater owners, studio executives,

lmmakers, and cinephiles that the lights may be starting to icker. As consumer tastes and demands

change, Hollywood is scrambling to adapt” (p. 1). With streaming services and in-home entertainment devices

such as Apple TV and Amazon Fire TV Stick on the rise, younger audiences are choosing the comfort and

convenience of home over a trip to the movie theater. However, despite an overall drop in ticket sales, movies

released within the past year continue to break box ofce records. Black Panther, which was released in

February 2018, had the highest-ever domestic opening weekend for a lm released in February, March, or

April, earning $201.8 million over its rst three days, not adjusted for ination (Vary, 2018). Additionally, prior

to the release of Black Panther, Wonder Woman became the highest-grossing superhero origin lm of all

time, with box ofce totals around $821 million (Hughes, 2017).

This article seeks to understand what entices audiences to view a lm in theaters versus at home

in today’s current technological climate of on-demand streaming services and large-screen televisions. The

collective spectatorship theory, which seeks to explain why audiences may enjoy watching lms together,

provides a framework for this research. This article proposes that audiences are particularly drawn to lms

in movie theaters when the content of the lm is relevant to previously existing aspects of popular culture.

Audiences want to experience these types of lms in a setting where there is a sense of community in order

to remain relevant and part of the overall conversation surrounding the lm.

Discovering Audience Motivations Behind Movie Theater Attendance by Emily Flynn — 95

II. Literature Review

This study draws from literature related to the rise of on-demand and subscription-based streaming

services, the current landscape of cinema attendance, and the theory of collective spectatorship, especially in

regards to movie viewership in theaters. Also relevant are studies related to online lm promotion and selling

an experience.

On-Demand and Subscription-Based Streaming Services

With a steady rise in digital media consumption, on-demand streaming services such as Netix, Hulu,

and Amazon prime continue to grow. According to Anderson (n.d.), video on-demand refers to “an interactive

system that allows viewers to select a movie from a database and watch it instantly on their television or

personal computer” (p. 1). Access to video on-demand is offered through a cable provider, or online through

a monthly subscription fee. Some devices such as Apple TV and Amazon Fire TV Stick charge a certain

fee per movie or television episode, but regardless of the platform, the movie or television show is available

to the viewer for instant consumption. According to a survey published by Statista in 2017, around 58% of

survey respondents in the U.S. reported having at least one subscription to a streaming service. Netix was

used by 50% of respondents, 29% reported using Amazon Prime, and 14% reported using Hulu (“Share of

consumers,” 2017).

The use of streaming services is especially prevalent in younger generations, specically those

between the ages of 18-29. Within this age group, about 61% watch television primarily through streaming

services on the Internet (Rainie, 2017). Additionally, the population’s media interactions are constantly

changing thanks to a rise in mobile phone usage, and entertainment viewership is no exception to this.

Researchers believe that the current boom in online video and music streaming is likely to change the entire

structure of the entertainment industry (Chen, Liu, & Chiu, 2017).

Despite the fact that many viewers of on-demand content are watching alone, some researchers

believe that it should still be considered a social experience due to the conversation and social connections

that form after one watches content. According to Steele, James, Burrows, Mantall and Bromham (2015),

“Even if consumers are watching on-demand alone, they are still likely to converse with others during or

after their experience. This has been greatly aided by the increase of present technological devices within

the home” (p. 219). However, despite the fact that delayed viewing of media allows for more consumers to

partake in conversations, it also has the tendency to exclude people from “water-cooler conversation,” as they

are afraid to hear spoilers. Therefore, both on social media and in-person, people feel excluded from cultural

conversation until they make the time to watch (Matrix, 2014).

Landscape of Cinema Attendance

Throughout history, movie theaters have represented a source of community for various

neighborhoods, cultures, and social groups. According to Luckett (2013), between 1908 and 1917, movies

had greater success when cinemas repositioned themselves as a “fundamentally local pleasure deeply linked

to family and community” (p. 130). These theaters encouraged customers to linger in the lobby before and

after the movie, and would often host local charity events, and showcase local businesses. By 1917, these

small neighborhood theaters were the main venue for feature lms (Luckett, 2013). As time progressed and

neighborhood theaters rose in popularity, moviegoing became a fun event for people of every social class.

It was a way to socialize and get out of the house without having to pay too much money, but still allowed

people to be part of a conversation. At the turn of the twentieth century, millions of new moviegoers viewed

lms as a language understood universally, and as something that transcended national class and boundaries

(Tratner, 2008).

From their very origin, movies and movie theaters were created with a sense of community in

mind. However, with the current increase in media technology, lms are no longer always released in the

so-called “traditional” sense (i.e. a lm goes to the theater before being released for everyday use). Tryon

(2009) suggests that in today’s digital landscape, “the optimal experience of watching movies with a group

of strangers in a darkened theater is about to disappear” (p. 4). For example, the Oscar-nominated lm

Mudbound received limited release in theaters at the same time it was released on Netix, which caused

an ongoing debate between theater owners and Netix producers, who wanted the lm to receive time

exclusively in theaters before release to the general public (Pearson, 2017).

96 — Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, Vol. 9, No. 2 • Fall 2018

As media technology continues to evolve, cinema attendance has slowly begun to reect this change.

Although movie box ofce numbers tend to uctuate from year to year, they are currently on the decline,

with 2017’s box ofce declining by 2.7% from the previous year (McNary, 2017). These numbers include the

release of Star Wars: The Last Jedi, which was expected to gain more revenue than it did.

Social Media and the Internet’s Inuence on Film Promotion

Social media in general has changed the landscape for conversation online given the fact that users

are able to discuss hot-button issues with large numbers of people in real time. This aspect of social media

plays a signicant role in the promotion of new lms, particularly after a lm is released. Sang Ho Kim,

Namkee Park and Seung Hyun Park (2013) conducted a study on the importance of word of mouth (WOM)

and critic reviews of movies and describes the signicance of their ndings:

Given that movies are an experience good whose product quality cannot be judged before

consumers attend it, moviegoers are likely to rely upon others’ reviews and opinions when they make

a movie consumption decision. Further, the recent development of the Internet and abundance of

social media make it possible for moviegoers to easily nd other people’s assessment and reviews

and exchange information about movies (p. 99).

Essentially, since the information is easily accessible online, moviegoers take into account whether

people who have previously viewed the movie gave it a positive review. Advertising tends to be the medium

that boosts a movie’s media presence, and media presence is what subsequently creates conversation in

social networks and forums. However, when people talk about a particular movie (regardless of whether or

not money has been spent to promote it), the number of people who go to see the movie is affected (Armelini

& Villanueva, 2011).

While it is clear that social media alone is not to be credited for all movie promotion success, it is

denitely the medium that fosters the most amount of conversation, which tends to be the highest-driving

factor for audiences to attend movies. Additionally, the Internet itself tends to motivate consumers to actively

seek information regarding movies, rather than passively watching the trailer on television (Xiaoge, Xigen, &

Nelson, 2005).

Selling an Experience

As consumer preferences continually evolve, newer generations have begun to show an interest in

paying money for experiences rather than material objects. In fact, this desire for experiences has grown in

popularity so much that experts have coined it as the “experience economy.” Experiences are often described

as a fourth economic category, and businesses have begun to adapt their services in order to position them

as experiences. According to Pine and Gilmore (1998), experiences are personal and unique, so they exist

“only in the mind of an individual who has been engaged on an emotional, physical, intellectual, or even

spiritual level” (p. 2). Most researchers believe that we haven’t quite reached a full experience economy, but

as younger generations continue to seek out new experiences, more and more businesses are changing their

marketing model to adapt.

It is also important to note that different experiences impact different senses, because they trigger

different emotions and levels of effort to comprehend. Movies are mentally demanding experiences, especially

those that require consumers to think about the greater social, political or cultural issues surrounding the story

(Sundbo & Darmer, 2008).

Theory of Collective Spectatorship

Although the theory of collective spectatorship is relatively new, it builds upon older theories regarding

how audiences perceive entertainment, particularly lms. In the 1970s and 1980s, some lm theorists

introduced the concept of “spectator theory” to explain the psychology behind the movie watching experience.

These earlier theories, developed by scholars such as Christian Metz, Jean-Louis Baudry and Roland Barthes,

all center on the idea that while watching a lm, spectators are silent, motionless, and expressionless.

Barthes compared lm viewing to a type of hypnosis where the viewer is not entirely conscious of what is

happening (De Luca, 2016). In contrast, theorist Vivian Sobchack disagreed with the notion that a spectator is

“motionless” and “silent,” and believed that the viewer is always conscious (De Luca, 2016).

Discovering Audience Motivations Behind Movie Theater Attendance by Emily Flynn — 97

Figure 1: Cinematic Firsts. Source: AMC Filmsite

The idea of “collective spectatorship” was originally introduced by Julian Hanich, who disagreed with

the idea that watching a lm was solely an individual experience, regardless of the medium. According to

Hanich (2014), the collective spectatorship theory states that audiences “can enjoy watching a lm collectively

without being fully aware of this fact” (p. 354). Essentially, the theory suggests that watching a lm should

be regarded as a joint action. Even though audiences may believe they are paying full attention to a lm,

the collective spectatorship theory proposes that the viewer hasn’t forgotten the other spectators present.

Audience awareness levels reach the very edges of one’s consciousness, because a viewer is usually not

actively thinking about those around them, but rather focusing on the lm. However, the idea of joint-viewing

is especially prevalent in moments of high emotion during a lm, as it becomes easier to sense a shared

emotion such as deep sadness or happiness (Hanich, 2014).

In light of the previous scholarship, this study seeks to explore communal aspects of movie viewing.

In particular, with increasing advances in subscription-based video on demand and declining movie theater

box ofce numbers, what elements inuence viewers to choose to watch a movie in theaters versus at home?

III. Methods

The author compiled a list of the top box ofce lms of all time, and the top box ofce lms within the

past six years. Both lists are adjusted for ination, and are based on calculations conducted by the website

Box Ofce Mojo. The purpose of comparing the two lists was to determine differences and similarities

between the most popular lms of all time, and lms that are currently considered popular. The author then

categorized each lm on both lists into the following categories: Pre-Existing Fandom, Remake/Sequel,

Superhero Movie, and Cinematic First. If a lm t more than one of the options, it was categorized more than

once. If a lm did not t any of the categories, it was listed as Other.

Pre-Existing Fandom refers to any lm where the basic storyline and characters had already been

introduced to audiences, either in an earlier movie, book, video game, or television show. Remake/Sequel

refers to any lm that continued or retold a storyline established in an earlier lm. Superhero Movie was

dened as any lm owned and created by Marvel or DC Comics. Cinematic First was dened as any lm that

incorporated new elements or concepts that had not been previously introduced in the lm industry at the time

(see Figure 1).

98 — Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, Vol. 9, No. 2 • Fall 2018

The purpose of categorizing the lms was to determine a few of the basic ways the lists differed from

one another, as well as what that may imply about current movie theater attendance.

In order to explore the impact that social media may have on the promotion of lms, the author also

compiled opening weekend box ofce numbers for the top lms listed and compared them to the total box

ofce gross. If a lm garners a high percentage of its revenues during the rst weekend, it may suggest a high

level of social media interaction during the days and weeks leading up to the lm’s opening.

IV. Findings

Comparison of Top Box Ofce Films

Figure 2: Top 20 box ofce lms of all time compared to top 20 box ofce lms in the past six years

The only movie to make both lists was Star Wars: The Force Awakens (highlighted in blue). All other

movies on the Top 20 Films of All Time list were released between the years of 1937 - 2009. Avatar is the only

other movie from the 2000s to make the all-time list.

Figure 3: General categories of top box ofce lms

Movies were sometimes placed in more than one category. For example, most superhero movies

were also classied as having a pre-existing fandom due to the fact that they are based on comic books.

However, the pre-existing fandom category does not exclusively include superhero movies since lms such

as The Hunger Games and Gone With the Wind also had pre-existing fan bases due to the fact that they were

based on books.

As the data shows, movies from the all-time list contain a lot of cinematic rsts. Gone With the Wind

continues to hold the highest box ofce success to date, and is often cited as the rst lm to use a more

Discovering Audience Motivations Behind Movie Theater Attendance by Emily Flynn — 99

Figure 4: Opening weekend box ofce gross in comparison to total box ofce gross (opening weekend

numbers not available for lms released prior to the mid-1970s.)

diverse technicolor palette, revolutionizing movies in color (Dirks, 2016). Additionally, Snow White and the

Seven Dwarfs was the rst full-length animated feature lm ever, a concept for which Walt Disney decided to

take a big (and successful) risk (Johnson, 2017). The top 20 movies of all-time list suggests that one of the

biggest driving factors for movie theater attendance was the opportunity to experience something new and

revolutionary.

In contrast, the movies with top box ofce performances from the past six years fell mainly into two

main categories: they were either a remake or sequel of a previously successful lm, and/or they had a pre-

existing fan base. In fact, the top two lms listed within Top 20 movies of the last six years are remakes or

sequels of lms appearing on the all-time list (Star Wars: The Force Awakens and Jurassic World).

Superhero movies also represented a large portion of the movies listed on the Top 20 movies in the

past six years list, with Marvel’s The Avengers ranking third and Black Panther a close fourth. However, there

is not a single superhero movie on the Top 20 Movies of All Time List.

Comparison of Opening Weekends

100 — Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, Vol. 9, No. 2 • Fall 2018

Generally, the opening weekends of newer movies made up a higher percentage of total box ofce

gross than older ones. In fact, Star Wars (1977) had a very limited release because movie theater owners

believed that it wouldn’t do well and didn’t want to show it. This changed once audiences began showing

great interest. Therefore, its opening weekend only comprised 1.48% of its total box ofce gross. Captain

America: Civil War’s opening weekend made up 43.9% of the movie’s total box ofce gross, making it the

highest out of all the movies listed.

V. Discussion

When considering ination, the top box ofce performers of all time were almost all released between

1937-1999 with Avatar (2009) and Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) being the only two exceptions. Half

of the movies on the Top 20 Movies of All Time list had some sort of historic cinematic rst, such as Snow

White and the Seven Dwarfs being the rst animated feature lm. This implies that audiences are drawn to

the theater in large amounts when something new and exciting is occurring. Conversely, the majority of the

popular movies released in the past six years were either superhero movies, or remakes of earlier lms (such

as Star Wars or Jurassic World). Current audiences aren’t necessarily as inspired to make a trip to the movie

theater for new content, but rather, they want to re-experience popular movies from the past. Part of the

reason for this could be the fact that it is easier for important plot points from Star Wars: The Force Awakens

to be spoiled than it is for a movie with a completely new storyline. Therefore, going to the theater to the view

the movie as soon as possible eliminates the chance of spoilers.

Additionally, as the theory of collective spectatorship suggests, people enjoy watching lms together

whether they are aware of it or not. Movies with an intense and loyal fandom like Star Wars tend to develop a

strong sense of community among viewers, meaning audiences want to experience the excitement of these

movies with others in the moment, rather than waiting to watch them on streaming services at home.

Superhero movies are also driving current audiences to movie theaters, a trend which Captain

America screenwriter Stephen McFeely says is because it is “a genre that you can do well now given the

world of computers and perhaps it’s also just a time in the sun. You went to the movies in the ’50s and ’60s

you went to a western. So at this point, you’re going to a superhero movie. It’s taking over that same black

hat, white hat myth-making surface” (Romano, 2015). Additionally, since superhero movies are based on old

comic books, they also have a pre-existing fan base and community with which to watch the lms. Therefore,

similar to the Star Wars franchise, people tend to watch these lms in a community setting.

Opening weekend box ofce numbers suggest that social media has an effect on movie theater

attendance. For movies released in the past six years, the percent of total revenue generated during the

opening weekend box is much higher than for movies of the past. This would imply that audiences are

attending movies during the opening weekend after hearing about the release ahead of time, very likely

through social media. Conversely, movies such as Star Wars and Jaws became popular by word of mouth

after their release because there were fewer media outlets through which to promote them.

This study has a number of limitations. Additional box ofce numbers were needed, since most

movies before the 1980s did not have opening weekend numbers reported. Some lms also had limited

release weekends before the actual release date, which were omitted from the study. Additionally, the

“cinematic rsts” category was dened largely by groundbreaking technical aspects, not for innovative

storylines or novel narrative structures. Future researchers may also want to utilize social media analytics

in order to determine a deeper evidence-based correlation between social media usage and movie theater

attendance.

VI. Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to determine some of the factors still drawing audiences to movie

theaters despite the increase in streaming service technology. It also sought to identify the differences

between popular box ofce lms of all time in comparison to top box ofce lms in the past six years in order

to further understand how audience preferences have changed.

Discovering Audience Motivations Behind Movie Theater Attendance by Emily Flynn — 101

The compilation of top box ofce lm data showed that recent popular movies were very different

from the top movies of all time. Today’s audiences are most interested in viewing superhero movies, or

remakes of old lms. In the past, audiences went to the movie theater to view lms that were considered

“groundbreaking,” but audiences now appear to want lms that already have a large fan base established,

such as Star Wars and Jurassic World. Audiences do not want to hear spoilers about lms where they

know the characters and plot well, so viewing it in the movie theater is a useful way to remain part of the

conversation in real time.

When considering the theory of collective spectatorship, movie theaters also elicit a sense of

community that people want to experience whether they realize it or not. Star Wars has a large, dedicated

fanbase (so much so that people will dress up for the premieres), thereby making it a movie people want

to view with their fellow fans. This is not as easy to do from one’s living room, and by the time the movie is

released to streaming services, the hype and excitement surrounding the movie’s release will have already

died down.

The movies chosen for this study only comprise a small portion of the top box ofce movies of all

time, so further research could be done with a more extensive list of movies over a longer time period.

However, the preliminary conclusions drawn from this study indicate that in order for movie theaters to remain

successful in the future, they need to brand themselves as an experience rather than just another medium to

view movies.

Acknowledgements

The author is thankful to Lorraine Ahearn, former professor at Elon University, for her supervision and

advice, without which the article could not be published. The author also appreciates numerous reviewers

who have helped revise this article.

References

Anderson, C. (n.d.). What is VOD technology? Retrieved March 2, 2018, from http://smallbusiness.chron.com/

vod-technology-14311.html

Armelini, G., & Villanueva, J. (2011). Adding social media to the marketing mix. IESE Insight, 9(9), 29–36.

Chen, Y.-M., Liu, H.-H., & Chiu, Y.-C. (2017). Customer benets and value creation in streaming services

marketing: a managerial cognitive capability approach. Psychology & Marketing, 34(12), 1101–1108.

Chuu, S. L. H., Chang, J. C., & Zaichkowsky, J. L. (2009). Exploring art lm audiences: A marketing analysis.

Journal of Promotion Management, 15(1/2), 212–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496490902835688

De Luca, T. (2016). Slow time, visible cinema: Duration, experience, and spectatorship. Cinema Journal,

56(1), 23–42.

Dirks, T. (2016). Background: Gone With The Wind (1939). Retrieved April 19, 2018, from http://www.lmsite.

org/gone.html

Dixon, W. W., & Foster, G. A. (2013). A short history of lm. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Gajanan, M. (2018, February 14). Oscars 2018: Here’s who has won the most Academy Awards ever. Time.

Retrieved April 19, 2018, from http://time.com/5148660/who-has-won-the-most-oscars/

Gomery, D. (1992). Shared pleasures: A history of movie presentation in the United States. Madison, WI:

University of Wisconsin Press.

Gone With the Wind: The essentials. (n.d.). Retrieved April 19, 2018, from http://www.tcm.com/this-month/

article/136724|0/Gone-With-the-Wind-The-Essentials.html

Haidee, W. (2016). Introduction: Entering the movie theater. Film History, 28(3), v–xi.

102 — Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, Vol. 9, No. 2 • Fall 2018

Hanich, J. (2014). Watching a lm with others: towards a theory of collective spectatorship. Screen, 55(3),

338–359. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hju026

Hansen, M. (2009). Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American silent lm. Cambridge, Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/elon-ebooks/detail.

action?docID=3300189

Johnson, M. L. (2014). The well-lighted theater or the semi-darkened room? Transparency, opacity and

participation in the institution of cinema. Early Popular Visual Culture, 12(2), 199–212. https://doi.org/

10.1080/17460654.2014.925248

Johnson, Z. (2017, December 21). 20 fun facts about Snow White on its 80th anniversary. Retrieved April

19, 2018, from http://www.eonline.com/news/901665/20-fun-facts-about-snow-white-and-the-seven-

dwarfs-on-its-80th-anniversary

Kim, S. H., Park, N., & Park, S. H. (2013). Exploring the effects of online word of mouth and expert reviews on

theatrical movies’ box ofce success. Journal of Media Economics, 26(2), 98–114. https://doi.org/10.1

080/08997764.2013.785551

Lang, B., & Lang, B. (2017, March 27). The reckoning: Why the movie business is in big trouble. Variety.

Retrieved March 14, 2018, from http://variety.com/2017/lm/features/movie-business-changing-

consumer-demand-studios-exhibitors-1202016699/

Luckett, M. (2013). Cinema and community: Progressivism, exhibition, and lm culture in Chicago, 1907-

1917. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press.

Mark, H. (2017, November 2). “Wonder Woman” is ofcially the highest-grossing superhero origin lm.

Forbes. Retrieved March 14, 2018, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/markhughes/2017/11/02/

wonder-woman-is-ofcially-the-highest-grossing-superhero-origin-lm/#686bb51cebd9

Matrix, S. (2014). The Netix effect: Teens, binge watching, and on-demand digital media trends. Jeunesse:

Young People, Texts, Cultures 6(1), 119-138. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/553418

Mayne, J. (2002). Cinema and Spectatorship. New York, NY: Routledge.

McNary, D. (2017, December 26). 2017 U.S. box ofce to fall to three-year low. Variety. Retrieved March 4,

2018, from http://variety.com/2017/lm/news/2017-u-s-box-ofce-three-year-low-1202648824/

Number of movie tickets sold in the United States and Canada from 2001 to 2017 (in millions). In Statista

- The Statistics Portal. Retrieved June 21, 2018, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/187076/

tickets-sold-at-the-north-american-box-ofce-since-2001/

Pearson, B. (2017, November 10). Netix’s Mudbound is getting a theatrical release. Retrieved March 2,

2018, from http://www.slashlm.com/netixs-mudbound-theatrical-release/

Pine, B. J., II, & Gilmore, J. H. (1998, July 1). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business

Review. Retrieved March 3, 2018, from https://hbr.org/1998/07/welcome-to-the-experience-economy

Rainie, L. (2017, September 13). About 6 in 10 young adults in U.S. primarily use online streaming to

watch TV. Pew Research Center. Retrieved March 1, 2018, from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-

tank/2017/09/13/about-6-in-10-young-adults-in-u-s-primarily-use-online-streaming-to-watch-tv/

Ramírez-Sánchez, R. (2008). Marginalization from within: Expanding co-cultural theory through the

experience of the Afro Punk. Howard Journal of Communications, 19(2), 89–104. https://doi.

org/10.1080/10646170801990896

Romano, N. (2015, January 15). Why superhero movies are popular right now, according to superhero

screenwriters. Retrieved April 19, 2018, from https://www.cinemablend.com/new/Why-Superhero-

Movies-Popular-Right-Now-According-Superhero-Screenwriters-69189.html

Share of consumers who have a subscription to an on-demand video service in the United States in

2017. In Statista - The Statistics Portal. Retrieved June 21, 2018, from https://www.statista.com/

statistics/318778/subscription-based-video-streaming-services-usage-usa/

Discovering Audience Motivations Behind Movie Theater Attendance by Emily Flynn — 103

Silver, J., & McDonnell, J. (2007). Are movie theaters doomed? Do exhibitors see the big picture as theaters

lose their competitive advantage? Business Horizons, 50(6), 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

bushor.2007.07.004

Steele, L., James, R., Burrows, R., Mantell, D. L. & Bromham, J. (2015). The consumption of on-demand.

Journal of Promotional Communications, 3(1), 219-24.

Sundbo, J., & Darmer, P. (2008). Creating Experiences in the Experience Economy. Northampton, MA:

Edward Elgar Publishing.

Tefertiller, A. (2017). Moviegoing in the Netix age: Gratications, planned behavior, and theatrical

attendance. Communication & Society, 30(4), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.30.3.27-44

Tratner, M. (2008). Crowd scenes: Movies and mass politics. New York, NY: Fordham University Press.

Tryon, C. (2009). Reinventing cinema: Movies in the age of media convergence. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers

University Press.

Vary, A. B. (2018, February 19). The historic success of “Black Panther” should change Hollywood forever.

Retrieved March 14, 2018, from https://www.buzzfeed.com/adambvary/black-panther-box-ofce

Xiaoge Hu, Xigen Li, & Nelson, R. A. (2005). The World Wide Web as a vehicle for advertising movies to

college students: An exploratory study. Journal of Website Promotion, 1(3), 115–122. https://doi.

org/10.1300/J238v01n03•09