Routledge Handbook of

Public Policy

This Handbook provides a comprehensive global survey of the policy process. Written by an

outstanding line-up of distinguished scholars and practitioners, the Handbook covers all aspects of

the policy process including:

theory – from rational choice to the new institutionalism

frameworks – network theory, the advocacy coalition framework, punctuated equilibrium

models and institutional analysis and development theory

key stages in the process – agenda-setting, formulation, decision-making, implementation

and evaluation

the roles of key actors and institutions

policy learning and policy dynamics from path dependency to process sequencing

This is an invaluable resource for all scholars, graduate students and practitioners in public policy

and policy analysis.

Eduardo Araral Jr. is Assistant Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy,

National University of Singapore.

Scott Fritzen is Associate Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National

University of Singapore.

Michael Howlett is Burnaby Mountain Chair in the Department of Political Science at Simon

Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada.

M Ramesh is Chair Professor of Govenance and Public Policy at the Hong Kong Institute of

Education and Visiting Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National

University of Singapore.

Xun Wu is Associate Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University

of Singapore.

Routledge Handbook of

Public Policy

Edited by

Eduardo Araral Jr.

Scott Fritzen

Michael Howlett

M Ramesh

Xun Wu

First published 2013

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

© 2013 selection and editorial matter, E. Araral Jr., S. Fritzen, M. Howlett, M. Ramesh, X.

Wu; individual chapters, the contributors

The right of E. Araral Jr., S. Fritzen, M. Howlett, M. Ramesh, X. Wu to be identified as

editors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and

Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any

form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented,

including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and

are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Routledge Handbook of Public Policy / edited by E. Araral ... [et al.].

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Policy sciences. I. Araral, Eduardo II. Title: Handbook of Public Policy.

H97.R68 2013

320.6–dc23

2012008846

ISBN: 978-0-415-78245-6 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-203-09757-1 (ebk)

Typeset in Bembo

by Taylor & Francis Books

Contents

List of illustrations ix

List of contributors xi

PART I

Introduction to the study of the public policy process: history

and method 1

1 Public policy debate and the rise of policy analysis

3

Michael Mintrom and Claire Williams

2 The policy-making process

17

Michael Howlett and Sarah Giest

3 Comparative approaches to the study of public policy-making

29

Sophie Schmitt

4 International dimensions and dynamics of policy-making

44

Anthony Perl

PART II

Conceptualizing public policy-making 57

5 State theory and the rise of the regulatory state

59

Darryl S.L. Jarvis

6 The public choice perspective

76

Andy Whitford

7 Institutional analysis and political economy

87

Michael D. McGinnis and Paul Dragos Aligica

8 Postpositivism and the policy process

98

Raul Perez Lejano

v

PART III

Modelling the policy process: frameworks for analysis 113

9 The institutional analysis and development framework

115

Ruth Schuyler House and Eduardo Araral Jr.

10 The advocacy coalition framework: coalitions, learning and policy change

125

Christopher M. Weible and Daniel Nohrstedt

11 The punctuated equilibrium theory of agenda-setting and policy change

138

Graeme Boushey

12 Policy network models

153

Chen-Yu Wu and David Knoke

PART IV

Understanding the agenda-setting process 165

13 Policy agenda-setting studies: attention, politics and the public

167

Christoffer Green-Pedersen and Peter B. Mortensen

14 Focusing events and policy windows

175

Thomas A. Birkland and Sarah E. DeYoung

15 Agenda-setting and political discourse: major analytical frameworks and

their application

189

David A. Rochefort and Kevin P. Donnelly

16 Mass media and policy-making

204

Stuart Soroka, Stephen Farnsworth, Andrea Lawlor and Lori Young

PART V

Understanding the formulation process 215

17 Policy design and transfer

217

Anne Schneider

18 Epistemic communities

229

Claire A. Dunlop

19 Policy appraisal

244

John Turnpenny, Camilla Adelle and Andrew Jordan

Contents

vi

20 Policy analytical styles 255

Igor S. Mayer, C. Els van Daalen and Pieter W.G. Bots

PART VI

Understanding the decision-making process 271

21 Bounded rationality and public policy decision-making

273

Bryan D. Jones and H.F. Thomas III

22 Incrementalism

287

Michael Hayes

23 Models for research into decision-making processes: on phases, streams,

rounds and tracks of decision-making

299

Geert R. Teisman and Arwin van Buuren

24 The garbage can model and the study of the policy-making process

320

Gary Mucciaroni

PART VII

Understanding the implementation process 329

25 Bureaucracy and the policy process

331

Ora-orn Poocharoen

26 Disagreement and alternative dispute resolution in the policy process

347

Boyd Fuller

27 Governance, networks and intergovernmental systems

361

Robert Agranoff, Michael McGuire and Chris Silvia

28 Development management and policy implementation: relevance beyond

the global South

374

Derick W. Brinkerhoff and Jennifer M. Brinkerhoff

PART VIII

Understanding the evaluation process 385

29 Six models of evaluation

387

Evert Vedung

30 Policy feedback and learning

401

Patrik Marier

Contents

vii

31 Randomized control trials: what are they, why are they promoted as the

gold standard for casual identification and what can they (not) tell us?

415

David Fuente and Dale Whittington

32 Policy evaluation and public participation

434

Carolyn M. Hendriks

PART IX

Policy dynamics: patterns of stability and change 449

33 Policy dynamics and change: the never-ending puzzle

451

Giliberto Capano

34 Policy trajectories and legacies: path dependency revisited

462

Adrian Kay

35 Process sequencing

473

Carsten Daugbjerg

36 Learning from success and failure?

484

Allan McConnell

Author index

495

Subject index 510

Contents

viii

Illustrations

Figures

9.1 A framework for institutional analysis 118

10.1 Flow diagram of the advocacy coalition framework 128

11.1 Incremental and punctuated policy change distributions 148

14.1 Comparative attention to terrorism 180

14.2 Dominant problem frames in school violence, by venue 182

16.1 Coverage of natural disasters/weather and pollution/climate change by year 210

18.1 Bibliographic analysis of 638 articles, book chapters and books citing Haas’s

1992 introductory article to the IO special edition 231

18.2 Bibliographic analysis of 638 articles, book chapters and books citing Haas’s

1992 introductory article to the IO special edition (subject areas receiving 11

citations or more) 232

20.1 Policy analysis tasks 258

20.2 Policy analysis styles 259

20.3 The underlying values and criteria of policy analysis 262

20.4 Overview of the complete hexagon model of policy analysis 266

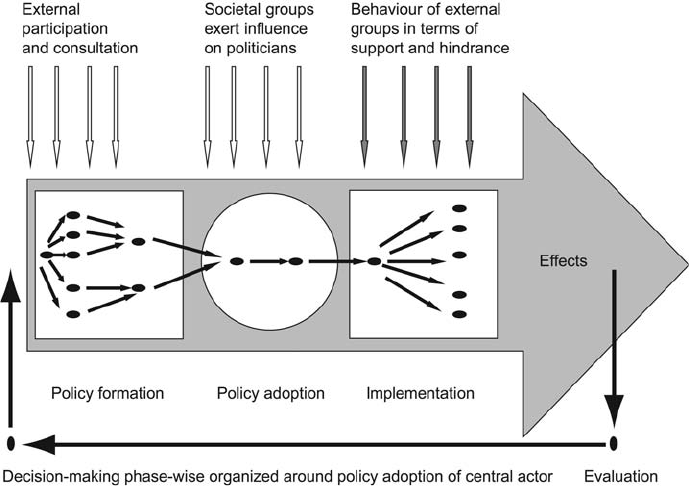

23.1 A depiction of four models for the analysis of decision-making processes 302

23.2 The concept of decision-making used in the phase model 304

23.3 The concept of decision-making used in the stream model 305

23.4 The concept of decision-making used in the rounds model 306

23.5 The concept of decision-making used in the tracks model 307

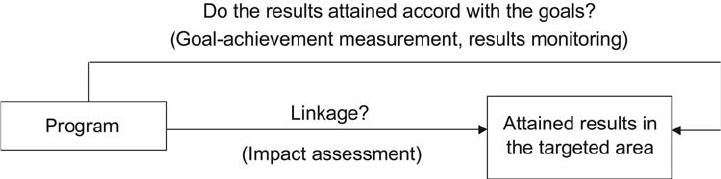

29.1 Goal-attainment model 389

29.2 Side-effects model with specified pigeonholes for side-effects 391

29.3 Potential stakeholders in local social welfare interventions 395

Tables

2.1 A taxonomy of substantive policy instruments 22

2.2 A resource-based taxonomy of procedural policy instruments 23

3.1 Subdisciplines of comparative public policy research 38

4.1 Supranational governance dynamics 52

5.1 General approaches to political phenomena and illustrative theoretical examples 60

5.2 A comparative typology of the interventionist and regulatory state 68

14.1 The substance of the agenda when events are or are not mentioned in testimony 181

14.2 Key issues addressed in aviation security legislation 183

ix

16.1 Coverage of natural disasters/weather and pollution/climate change 211

20.1 Positive and negative images of the policy analyst 265

22.1 Four quadrants of policy change 289

22.2 A typology of decision environments 291

23.1 Comparative perspectives on the phase model, the stream model and the

rounds model 308

23.2 Events in decision-making on the Betuwe line and a fourfold research result 314

28.1 Competing perspectives on development management 378

36.1 The three realms of policy success 488

Box

20.1 Translation of values into quality criteria 264

List of illustrations

x

Contributors

Camilla Adelle is a Senior Research Associate in the Science, Society and Sustainability Research

Group, School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK.

Robert Agranoff is an Emeritus Professor in the School of Public and Environmental Affairs,

Indiana University, Bloomington, USA and Catedrático in the Government and Public

Administration Program, Instituto Universitario Ortega y Gasset, Madrid, Spain. He joined

Indiana University in 1980 from Northern Illinois University and started at Ortega y Gasset in

1990. He continues to be professionally active, specializing in public administration, inter-

governmental relations and management, and public network studies.

Paul Dragos Aligica is a Senior Research Fellow at the Mercatus Center, a Senior Fellow on

the F.A. Hayek Program for Advanced Study in Philosophy, Politics and Economics, a Faculty

Fellow at the James Buchanan Center for Political Economy at George Mason University,

USA, and an Adjunct Fellow at the Hudson Institute, Washington DC, USA. He studies

institutional analysis and institutional theory.

Eduardo Araral Jr. is an Assistant Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public

Policy, National University of Singapore. He is interested in the study of institutions for

collective action from local to international levels and covering a variety of areas from the

commons, international security, climate adaptation, bureaucracy and aid and water resources

management.

Thomas A. Birkland is William T. Kretzer Distinguished Professor at the School of

International and Public Affairs, North Carolina State University, USA where he teaches

courses on the public policy process, environmental politics and policy, and disaster policy

and management. His research has focused on how and to what extent major ‘focusing

events’ influence policy agendas. His current research seeks to connect focusing events and

policy failure to policy change and learning. He is the author of An Introduction to the Policy

Process (2nd edn, M.E. Sharpe), and After Disaster and Lessons of Disaster (both Georgetown

University Press), and is co-editor with Todd Schaefer of The Encyclopedia of Mass Media

(CQ Press).

Pieter Bots is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management

(TPM), Delft University of Technology, Netherlands. His expertise lies mainly in conceptual

models and computer-based tools to support problem formulation and multi-actor systems

analysis, preferably in combination with serious gaming/simulation.

xi

Graeme Boushey is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at the Uni-

versity of California, Irvine, USA, where he teaches courses in American politics, Californian

and state politics, public policy, and research methodology. His research focuses on public

policy processes and political decision-making in American federalism. His teaching and research

are organized around practical and theoretical questions of state and federal policy-making.

Derick W. Brinkerho ff is a Distinguished Fellow in International Public Management, at the

Research Triangle Institute and has more than 30 years of experience with public management

issues in developing and transitioning countries, focusing on policy analysis, programme imple-

mentation and evaluation, participation, institutional development, democratic governance, and

change management. He is co-editor of the journal Public Administration and Development, and

serves on the editorial boards of Public Administration Review and International Review of Adminis-

trative Sciences. He also holds an associate faculty appointment at the Trachtenberg School of

Public Policy and Public Administration, George Washington University, USA.

Jennifer M. Brinkerhoff is Professor of Public Administration and International Affairs and

Co-Director, GW Diaspora Program at the Elliott School of International Affairs at George

Washington University, USA. She teaches courses on public service, international development

policy and administration, development management and organizational behaviour. She is par-

ticularly keen on encouraging people to pursue service careers thoughtfully, grounding their

commitment to change in self-awareness and working in community. She is the author

of Digital Diasporas: Identity and Transnational Engagement (Cambridge University Press, 2009)

and Partnership for International Development: Rhetoric or Results? (Lynne Rienner, 2002); the

editor of Diasporas and Development: Exploring the Potential (Lynne Rienner, 2008); and co-editor

of NGOs and the Millennium Development Goals: Citizen Action to Reduce Poverty (Palgrave

Macmillan, 2007).

Giliberto Capano is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the University of

Bologna, Italy. He specializes in comparative higher education, public administration and the-

ories of policy-making. He has recently edited (with Elisabetta Gualmini) La Pubblica amminis-

trazione in Italy (Il Mulino, 2011) and European and North American Policy Change (Routledge,

2009) with Michael Howlett.

Carsten Daugbjerg is a Professor at the Institute of Food and Resource Economics, University

of Copenhagen, Denmark. His research area is comparative public policy with a particular

interest in historical institutitionalism, policy networks, policy instruments and ideas in public

policy. His empirical research has focused on agricultural policy reform, trade negotiations in

the World Trade Organization, global food regulation, government interest group relations and

environmental policy.

Sarah E. DeYoung is a doctoral student at North Carolina State University, USA, in the

Psychology in the Public Interest programme. Her research interests are disaster policy and

community disaster preparedness.

Kevin P. Donnelly is Assistant Professor of Political Science and Public Administration at

Bridgewater State University, USA. His previous work includes Foreign Remedies: What the

Experience of Other Nations Can Tell Us about Next Steps in Reforming U.S. Health Care (2012),

co-authored with David A. Rochefort.

List of contributors

xii

Claire A. Dunlop teaches politics and administration at the University of Exeter, UK. Pre-

viously she worked for the Scottish Consumer Council and the Scottish Executive. She has worked

and published widely on issues related to knowledge use in governments and policy appraisal.

Her recent work has appeared in Political Studies, Public Management Review and Regulation and

Governance.

Stephen J. Farnsworth is Professor of Political Science and International Affairs at the George

Washington University, USA, where he directs the university’s Center for Leadership and

Media Studies. He is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics and a former

Fulbright Scholar at McGill University, Canada.

David Fuente is a PhD student in the Department of City and Regional Planning at the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA.

Boyd Fuller is an Assistant Professor in the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the

National University of Singapore. His research focuses on the resolution of difficult water,

environmental and land conflicts when stakeholders have apparently irreconcilable differences in

values, identities or culture. He is currently researching the use of traditional and innovative

dispute resolution techniques for public disputes in post-conflict areas of Southeast Asia. His

previous research examined the mediation of intractable environmental conflicts in the United

States. He has eight years’ experience designing and implementing water supply projects in

developing countries.

Sarah Giest is a PhD student in the Department of Political Science at Simon Fraser University

in Burnaby, BC, Canada. She works on innovation systems and networks with special reference to

comparative biotechnology clusters.

Christoffer Green-Pedersen is Professor of Political Science at Aarhus University, Denmark.

His research focuses on agenda-setting dynamics and party competition.

Michael Hayes is Professor of Political Science at Colgate University, USA, specializing in

interest group theory, incrementalism and policymaking, effects of public opinion on the

legislative process. He has taught at Lawrence University and Rutgers University and pub-

lished Incrementalism and Public Policy; Lobbyists and Legislators; various book chapters and

articles (Journal of Politics, Polity) on the influence of interest groups and public opinion on

policy-making.

Carolyn M. Hendriks’s work examines the democratic practices of contemporary governance,

particularly with respect to public deliberation, inclusion and political representation. She

has taught and published widely on the application and politics of inclusive and deliberative

forms of citizen engagement. With a background in both political science and environmental

engineering, Carolyn has a particular interest in the governance of the environment, as well as

science and technology issues. She has recently published a book on the practice of delib-

erative democracy entitled The Politics of Public Deliberation: Citizen Engagement and Interest

Advocacy (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

Ruth Schuyler House is a PhD student in the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the

National University of Singapore. Her research concentrates on the fields of water and

List of contributors

xiii

sanitation policy. She is also interested in the changing face of governance and emerging

opportunities for the private sector to assume responsibility for and lend valuable knowledge

and resources to addressing poverty alleviation.

Michael Howlett is Burnaby Mountain Professor in the Department of Political Science at

Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada. He has published widely, most recently

Designing Public Policies: Principles and Instruments (Routledge, 2011) and is co-editing with David

Laycock Regulating Next Generation Agri-Food Biotechnologies, Lessons from European, North Amer-

ican and Asian Experiences (Routledge, 2012)

Darryl S.L. Jarvis is Vice-Dean of Academic Affairs and Associate Professor at the Lee Kuan

Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore and specializes in risk analysis

and the study of political and economic risk in Asia, including investment, regulatory and

institutional risk analysis. He has been a consultant to various government bodies and business

organizations, and for two years was a member of the investigating team and then chief

researcher on the Building Institutional Capacity in Asia (BICA) project commissioned by the

Japanese Ministry of Finance.

Bryan D. Jones’s research interests centre on the study of public policy processes, American

governing institutions, and the connection between human decision-making and organizational

behaviour. Before joining the Department of Government at the University of Texas, Austin,

USA, in 2008, Professor Jones was the Donald R. Matthews Distinguished Professor of Amer-

ican Politics at the University of Washington. Previously, he was Distinguished Professor and head

of department at Texas A&M University, and also taught at Wayne State University. His books

include Politics and the Architecture of Choice (2001) and Reconceiving Decision-Making in Democratic

Politics (1994), both winners of the APSA Political Psychology Section Robert Lane Award; The

Politics of Attention (co-authored with Frank Baumgartner, 2005); Agendas and Instability in

American Politics (co-authored with Frank Baumgartner, 1993), winner of the 2001 Aaron

Wildavsky Award for Enduring Contribution to the Study of Public Policy of the American

Political Science Association’s Public Policy Section and The Politics of Bad Ideas (co-authored

with Walt Williams).

Andrew Jordan is Professor of Environmental Politics at the University of East Anglia, Nor-

wich, UK. He is interested in the governance of environmental problems in many different

contexts, but especially that of the European Union.

Adrian Kay is an Associate Professor in the Crawford School at the Australian National Uni-

versity and Director of its Policy and Governance Program. His current research interests are in

the relationships between international and domestic policy processes, with a particular empiri-

cal focus on health and agriculture.

David Knoke is a Professor in the Department of Sociology at University of Minnesota, USA,

where he teaches a graduate network analysis seminar that attracts students from diverse dis-

ciplines. He co-authored Network Analysis (1982) and has published 15 books and more than

100 articles and book chapters, primarily on organizations, networks, politics and social statistics.

He was principal co-investigator on several National Science Foundation-funded projects on

voluntary associations, lobbying organizations in national policy domains, and organizational

surveys of diverse establishments.

List of contributors

xiv

Andrea Lawlor is a PhD student the Department of Political Science McGill University, Canada

specializing in media and public policy. Other research interests include political parties, party

financing and Quebec politics. Her research can be found in Canadian Public Administration.

Raul Perez Lejano is an Associate Professor of Planning, Policy and Design in the School of

Social Ecology at the University of California, Irvine, USA. His research is currently in envir-

onmental planning, new decision models for explaining non-state/non-market institutions,

relational models of collective action, planning theory, institutional models of care and justice

research.

Patrik Marier holds a Tier-II Canada Research Chair (CRC) in Comparative Public Policy. His

research focuses broadly on the impact of changing demographic structures on reforms to the

welfare state in comparative contexts. His earlier work examined the politics of pension reform in

a number of countries including Sweden, Canada, Mexico and the United States. His current

research looks more broadly at the impact of ageing populations on a number of public policy

fields including education, health care and labour policy across comparative cases.

Igor S. Mayer is a Senior Associate Professor in the Faculty of Technology, Policy and Man-

agement (TPM) at Delft University of Technology, Netherlands. He is also the director of the

TU-Delft Centre for Serious Gaming.

Allan McConnell is Professor in the Department of Government and International Relations,

University of Sydney, Australia. He has published extensively on policy and political issues

surrounding crises, disasters, failures and fiascoes, as well as the more upbeat topic of policy success.

Michael D. McGinnis is Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in the Department of

Political Science at Indiana University, Bloomington, USA. He studies the unique contributions

that faith-based organizations make to the design and implementation of public policy related to

humanitarian relief, development assistance, peace-building and reconciliation in troubled

regions of the world, as well as standard public services in education, health care and welfare

assistance in societies less directly challenged by the ravages of war.

Michael McGuire is Professor in the School of Public and Environmental Affairs, Indiana

University, Bloomington, USA. He works on intergovernmental and interorganizational colla-

boration and networks and has published widely on public management topics. His recent

publications on the subject have appeared in Public Administration Review and Public Administra-

tion among others.

Michael Mintrom is Professor of Public Sector Management at Monash University and the

Australia and New Zealand School of Government. He is the author of Contemporary Policy

Analysis (Oxford University Press, 2012), People Skills for Policy Analysts (Georgetown University

Press, 2003), and Policy Entrepreneurs and School Choice (Georgetown University Press, 2000).

Peter B. Mortensen is Associate Professor of Political Science at Aarhus University. His

research focuses on agenda-setting and public policy.

Gary Mucciaroni is a member of the Political Science Department at Temple University,

USA and was Department Chair between 2005 and 2010. The focus of his research and

List of contributors

xv

publication is the politics of public policy-making in the United States – examining the forces

and actors that impinge upon the policy choices of government. He has published The Political

Failure of Employment Policy, 1945–1982, Reversals of Fortune: Private Interests and Public Policy,

Deliberative Choices: Debating Public Policy in Congress and Same Sex, Different Politics: Issues and

Institutions in the Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Rights.

Daniel Nohrstedt is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the Department of Gov-

ernment, Uppsala University, Sweden. His research is primarily focused on crisis and learning,

intelligence issues, counter-terrorism policy and the public policy process.

Anthony Perl is Professor and Director of the Urban Studies Program and a member of the

Department of Political Science at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada. His current

research crosses disciplinary and national boundaries to explore the policy decisions that affect

transportation, cities and the environment. His latest book, co-authored with Richard Gilbert,

is Transport Revolutions: Moving People and Freight Without Oil published by New Society Pub-

lishers in 2010.

Ora-orn Poocharoen is an Assistant Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy

at the National University of Singapore. Her research interests include public management

reform, public administration theory, organization theory, comparative public administration

and public policy analysis.

David A. Rochefort is Arts and Sciences Distinguished Professor of Political Science at

Northeastern University, USA. His previous works include Foreign Remedies: What the Experience

of Other Nations Can Tell Us about Next Steps in Reforming U.S. Health Care (2012), written with

Kevin P. Donnelly, and co-editor with Roger W. Cobb of The Politics of Problem Definition (1994),

among other titles.

Sophie Schmitt is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Comparative Public Policy

and Administration, University of Konstanz, Germany, and specializes in comparative public

policy with a particular focus on environmental and social policy and regulation. She has

recently published articles in the Journal of European Public Policy and European Integration Online

Papers.

Anne Schneider is a Professor in the School of Justice at the University of Arizona, USA and

specializes in public policy and the role of policy in democracy. She and long-time co-author

Helen Ingram are the authors of Policy Design for Democracy (Kansas University Press), and

Deserving and Entitled (SUNY Press), and ‘The social construction of target populations,’ American

Political Science Review, June 1993.

Chris Silvia looks at interorganizational approaches to service delivery through the lens of

emergency management. His research aims to help public managers, who are more accustomed

to leading in hierarchical organizations, successfully contribute to leading networks. His recent

research has appeared in Journal of Public Affairs Education, State and Local Government Review and

Public Administration Review.

Stuart Soroka is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Sciences, McGill University,

Montreal, Canada.

List of contributors

xvi

Geert R. Teisman is currently Professor of Public Administration and Complex Decision

Making and Process Management at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands, and was

previously Professor of Spatial Planning at the University of Nijmegen. He is member of the

board of Habiforum, a joint venture between science, private sector and public authorities which

explores possibilities of multiple land use. He is Scientifi c Director of Living with Water, a

foundation which governs a variety of projects in which water system improvement is one of its

important aims. He is member of the executive board of Netlipse, a European knowledge

exchange network in the field of infrastructure project management. He regularly advises gov-

ernments and private organizations on complex decision-making, strategic planning, public-

private partnerships, process management, intergovernmental co-operation in metropolitan areas

and policy evaluation.

H.F. Thomas III is a PhD student at Pennsylvania State University, USA, working on information,

science and technology policy issues.

John Turnpenny is a Senior Research Associate at the University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK.

His research focuses on the relationship between science, evidence and public policy-making.

Arwin van Buuren is an Associate Professor at the Department of Public Administration at

the Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands. His research focuses on the domain of

water and climate governance. He is especially interested in the way in which complex

governance processes are organized and how the relationship between knowledge and govern-

ance can be optimized. He combines fundamental with applied research. His recent articles

have been published in International Journal of Project Management, International Journal of Public

Management, Public Management Review, Climatic Change and Environmental Impact Assessment

Review.

Els van Daalen is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Technology, Policy and Manage-

ment (TPM), Delft University of Technology, Netherlands. Her research interests include

system dynamics modelling and the use of models in policy-making.

Evert Vedung is an Emeritus Professor of Political Science and a specialist in housing policy at

Uppsala University, Sweden. He has held posts at Mälardalen University College and the

University of Uppsala. He has been a board member of the Swedish Evaluation Society since its

foundation.

Christopher M. Weible is an Assistant Professor in the School of Public Affairs at the Uni-

versity of Colorado Denver, USA. He teaches courses in environmental policy and politics,

public policy, policy processes, policy analysis, and research methods and design. His area of

research is in policy change, learning, political behaviour, coalitions and networks, institutions and

collective action, collaborative governance, and the role of scientific and technical information

in the policy process.

Andy Whitford is a Professor of Public Administration and Policy in the School of Public and

International Affairs at the University of Georgia, USA. He concentrates on research and

teaching in organizational studies and public policy, with specific interest in organization theory,

models of decision-making and adaptation, and the political control of the bureaucracy. His

interests in public policy include environmental, regulation and public health policy. He has

List of contributors

xvii

particularly strong interest in the use of simulation and experimental methods for understanding

organizational behaviour and individual choice.

Dale Whittington is a Professor of Environmental Sciences and Engineering, City and

Regional Planning, and Public Policy, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

USA. Since 1986 he has worked for the World Bank and other international agencies on the

development and application of techniques for estimating the economic value of environmental

resources in developing countries, with a particular focus on water and sanitation and vaccine

policy issues.

Claire Williams is a policy advisor at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. She

has previously published in Policy and Society.

Chen-Yu Wu is a graduate student in the Department of Sociology at the University of

Minnesota, USA, and was a Teaching Assistant for the courses ‘Introduction to Sociology’ and

‘Basic Social Statistics.’

Lori Young is a PhD student in the Annenberg School of Communication at the University of

Pennsylvania, USA. Her published work includes studies of foreign news reporting in Canada

and the United States and has appeared in journals such as The International Journal of Press/Pol-

itics.

List of contributors

xviii

1

Public policy debate and the rise

of policy analysis

Michael Mintrom and Claire Williams

Since the mid-1960s, an increasingly large number of people, trained in the humanities and

social sciences, have come to devote their professional lives to producing policy advice. This is a

global phenomenon, although until recently the intensification of activities associated with

policy advising has been most pronounced in the United States. As government demand for

well-trained policy analysts and advisors has risen, universities have sought to provide relevant

graduate-level training.

The rise of policy analysis is usefully construed as a movement. Use of this term implies a

deliberate eff ort on the part of many people to reconceive the role of government in society

and renegotiate aspects of the relationships that exist between individuals, collectivities and

governments. However, the claim that there is a policy analysis movement should not be taken

to imply either consistency of purpose or a deliberate striving for coordination among producers

of policy analysis. While not directly comparable in a political sense with other social movements,

the policy analysis movement has been highly influential. It has served to transform the advice-

giving systems of governments, altered the nature of policy debate, and, as a consequence,

challenged informal yet long-established advising practices through which power and influence

flow. The profundity of this transformation has often eluded the attention of social and political

commentators. That is because the relevant changes have caused few immediate or obvious rup-

tures in the processes and administrative structures typically associated with government or,

more broadly speaking, public governance.

Early representations of policy analysis tended to cast it as a subset of policy advising. As such,

policy analysis was seen primarily as an activity conducted inside government agencies with the

purpose of informing the choices of a few key people, principally elected decision-makers

(Lindblom 1968; Wildavsky 1979). Today, the potential purposes of policy analysis are under-

stood to be much broader. Many more audiences are seen as holding interests in policy and as

being open to – indeed demanding of – appropriately presented analytical work (Radin 2000).

Beyond people in government, people in business, members of non-profit organizations, and

informed citizens all constitute audiences for policy analysis. While policy analysts were once

thought to be mainly located within government agencies, today policy analysts also can be found

in most organizations that have direct dealings with governments, and in many organizations

where government actions significantly influence the operating environment. In addition, many

3

university-based researchers, who tend to treat their peers and their students as their primary

audience, conduct studies that ask questions about government policies and that answer them

using forms of policy analysis. Given this, an appropriately encompassing definition of con-

temporary policy analysis needs to recognize the range of topics and issue areas policy analysts

work on, the range of analytical and research strategies they employ, and the range of audiences

they seek to address. In recognizing the contemporary breadth of applications and styles of

policy analysis, it becomes clear that effective policy analysis calls for not only the application of

sound technical skills (Mintrom 2012), but also deep substantive knowledge, political percep-

tiveness and well-developed interpersonal skills (Mintrom 2003). Although producing high-

quality, reliable advice remains a core expectation for many policy analysts, advising now

appears as a subset of the broader policy analysis category. The transition from policy analysis as

a subset of advising to advising as a subset of analysis represents a significant shift in orientation

and priorities from earlier times.

In what follows, we first review the sources of increasing demand for policy analysis. We then

review the growth and adaptation in the supply of policy analysis that has occurred in response

to this demand. We conclude by discussing the current state of public policy debate and the

likely future trajectory of both the practice of policy advising and the training of policy analysts.

Throughout, we take the United States as our main point of reference. However, we have also

sought to demonstrate the comparative relevance of our argument. We have done this by discussing

the international embrace of New Public Management orthodoxy (from the late 1970s to the

mid-1990s) and government responses to the global financial crisis (from 2007 into 2012).

Before proceeding, it is useful to define terms. For the purposes of this discussion, public policies

are considered to be any actions taken by governments that represent previously agreed responses

to specified circumstances. Governments design public policies with the broad purpose of

expanding the public good (Howlett 2011; Mintrom 2012). Policy studies refers to research on

policy topics and analytical work conducted primarily by university-based researchers with the

goal of critically assessing past, present and proposed policy settings. Policy studies can be under-

taken by researchers in many disciplinary or cross-disciplinary settings. They can draw upon a

range of analytical and interpretative methodologies. Policy studies may be historical and com-

parative in their scope. The term policy sciences refers to the subset of analytical techniques

devised in the social sciences that have been applied to understanding the design, implementa-

tion and evaluation of public policies. Policy analysis is here discussed as work intended to

advance knowledge of the causes of public problems, alternative approaches to addressing them,

the likely impacts of those alternatives, and trade-offs that might emerge when considering appro-

priate governmental responses to those public problems. Policy advising is defined here as the

practice of providing information to decision-makers in government, with the intention of

improving the base of knowledge upon which decisions are made. While policy advising need

not be based upon rigorous policy analysis, over recent decades such policy analysis has come to

play a more central part in the development of advice for decision-makers.

The evolving demand for policy analysis

Demand for policy analysis has been driven mostly by the emergence of problems and by

political conditions that have made those problems salient. Early in the development of policy

analysis techniques, the people who identified the problems that needed to be addressed tended

to be government officials. They turned to academics for help. Frequently, those academics

deemed to be most useful, given the problems at hand, were economists with strong technical

skills, who had the ability to estimate the magnitude of problems, undertake statistical analyses,

Mintrom and Williams

4

and determine the costs of various government actions. During the twentieth century, as transpor-

tation, electrification and telecommunications opened up new opportunities for market exchange,

problems associated with decentralized decision-making became more apparent (McCraw 1984).

Meanwhile, as awareness grew of the causes of many natural and social phenomena, calls emerged

for governments to establish mechanisms that might effectively manage various natural and

social processes. Many matters once treated as social conditions, or facts of life to be suffered,

were transformed into policy problems (Cobb and Elder 1983). Together, the increasing scope

of the marketplace, the increasing complexity of social interactions, and expanding knowledge

of social conditions created pressures from a variety of quarters for governments to take the lead

in structuring and regulating individual and collective action. Tools of policy analysis, such as

the analysis of market failures and the identification of feasible government responses, were devel-

oped to guide this expanding scope of government. Yet as the reach of policy analysis grew,

questions were raised about the biases inherent in some of the analytical tools being applied. In

response, new efforts were made to account for the effects of policy changes, and new voices

began to contribute in significant ways to policy development. To explore the factors prompt-

ing demand for policy analysis, it is useful to work with a model of the policy-making process.

A number of conceptions of policy-making have been developed in recent decades. Here, we

apply the ‘stages model’, where five stages are typically posited: problem definition, agenda setting,

policy adoption, implementation, and evaluation (Eyestone 1978).

Initial demands for policy analysis were prompted by growing awareness of problems that

governments could potentially address. Questions inevitably arose concerning the appropriateness

of alternative policy solutions. Thus, in the United States in the 1930s, as the federal government

took on major new roles in the areas of regulation, redistribution and the financing of infra-

structural development, the need arose for high quality policy analysis. With respect to regulatory

policy, concerns about the threat to the railroads of the emerging trucking industry prompted

the expansion of the Interstate Commerce Commission (Eisner 1993). This body employed lawyers

and economists who helped to devise an expanding set of regulations that eventually covered

many industries. Although the American welfare state has always been limited compared with

welfare states elsewhere, especially those within Europe, its development still required concerted

policy analysis and development work on the part of a cadre of bureaucrats (Derthick 1979).

Initially, much of the talent needed to fill these positions was drawn from states like Wisconsin,

where welfare policies had been pioneered by Robert LaFollette. As the role of the United States

government in redistribution expanded, policy analysts swelled the ranks of career bureaucrats in

the Treasury, the Office of Management and Budget, and the Department of Health and Human

Services. Meanwhile, benefit-cost analysis, a cornerstone of modern policy analysis and a core

component of public economics, was developed to help in the planning of dam construction in

the Tennessee Valley in the 1930s. Politicians at the time worried that some dams were being

built mainly to perpetuate the flow of cash to construction companies rather than to meet growing

demand for electricity and flood control (Eckstein 1958). The broad applicability of the tech-

nique soon became clear and its use has continually expanded. At the same time, efforts to improve

the sophistication of the technique, and to develop variations on it that are best suited to different

sets of circumstances have also continued to occur (Boardman et al. 2006; Carlson 2011).

Several features of policy development, the politics of agenda setting, and the policymaking

process have served over time to increase demand for policy analysts. The dynamics at work

have been similar to those through which an arms race generates ongoing and often expanding

demand for military procurements. In Washington, DC, the growing population of policy analysts

employed in the federal government bureaucracy led to demand elsewhere around town for

policy analysts who could verify or contest the analysis and advice emanating from government

Public policy debate

5

agencies. A classic example is given by the creation of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

This office was established as an independent resource for Congress that would generate analysis

and advice as a check on the veracity of the analyses prepared and disseminated by the execu-

tive-controlled Office of Management and Budget (Wildavsky 1992). The General Accounting

Office – renamed in 2004 the Government Accountability Office – was also developed to

provide independent advice for Congress. The purview of this Office has always been broader

than that of the Congressional Budget Office.

As the analytical capabilities available to elected politicians grew, groups of people outside

government but with significant interests in the direction of government policy began devoting

resources to the production of high-quality, independent advice. Think tanks, like the Brook-

ings Institution and the American Enterprise Institute, established in the 1920s and 1940s

respectively, and both still going strong, represent archetypes of many independent policy shops

now located in Washington, DC (Smith 1991).

Today, due to the knowledge base of think tanks and their entrepreneurial capacity, their

staff and affiliates are often regarded as members of a select few who dominate policy. Networks

between non-governmental policy experts and politicians in the United States are strengthened

through appointments into government departments – often described as a “revolving door”–

in which policy experts frequently move into and out of key positions in the government over

successive presidential elections. Therefore, United States think tanks are often viewed as

trustworthy sources of advice to the administration because of their deep connections, the star

status of some of their people, and their sophisticated influence efforts.

It is useful to note that the roles, character, and effectiveness of think tanks are shaped by

country-specific institutional and political factors. In the United States, most think tanks tend to

serve both as ‘watch dogs’ and as ‘idea brokers’; how much they exhibit either characteristic

depends largely on their alignment or lack of alignment with the political colours of the current

Administration. In contrast, most think tanks operating in Asian countries tend to view their

role as ‘regime-enhancing’ (Stone 2000; Stone and Denham 2004; Abelson 2004).

Parliamentary systems, found most conspicuously in Commonwealth countries, tend to

exhibit greater centralization of legislative power and accountability than systems like that of the

United States where the separation of powers is a fundamental characteristic of governance.

Centralization of power gives those in leadership positions greater control over policy. The

electoral system can serve to either enhance or diminish the power that those in government

exercise over policy development. This has been clearly exhibited in the case of New Zealand,

where a switch in 1996 from first-past-the-post to mixed member proportional representation

in parliament changed the political landscape. Due to the increased diversity and number of

actors in the policy-making process, policy deliberation now tends to be longer and more con-

sultative, requiring greater input from a wider range of political actors and interest groups (Boston

et al. 2003). This change in the electoral system has resulted in greater demand for policy ana-

lysis. The potential for influence among political parties, members of parliament and interest

groups outside the government has led them to build analytical strengths that had previously

been almost the exclusive preserve of government departments.

The American constitution has an enshrined checks and balances system including a federal

and presidential system which is highly decentralized and fragmented. Establishment of the

Congressional Policy Advisory Board in 1998 has provided a further channel for experts to

share their advice with members of Congress as three-quarters of the policy experts on the

board are from think tanks. Combined with weak parties and considerable employee turnover,

the United States government is open to a host of government and non-government experts

engaging in policy-making (McGann and Johnson 2006).

Mintrom and Williams

6

Although policy analysis is often understood as work that occurs before a new policy or

programme is adopted, demand for policy analysis has also been driven by interest in the

effectiveness of government programmes. The question of what happens once a policy idea has

been adopted and passed into law could be construed as too operational to deserve the attention

of policy analysts. Yet, during the past few decades, elements of implementation have become

recognized as vital for study by policy analysts (Bardach 1977; Lipsky 1984; Pressman and

Wildavsky 1973). In part, this has been led by results of programme evaluations, which have

often found policies not producing their intended outcomes, or worse, creating whole sets of

unintended and negative consequences. One important strain of the work devoted to assessing

implementation has contributed to what is now known as the ‘government failure’ literature

(Niskanen 1971; Weimer and Vining 2005; Wolf 1979). The possibility that public policies

designed to address market failures might themselves create problems led to a greater respect for

market processes and a degree of scepticism on the part of policy analysts towards the remedial

abilities of government (Rhoads 1985). In turn, this required policy analysts to develop more

nuanced understandings of the workings of particular markets. The government failure litera-

ture has led to greater interest in government efforts to simulate market processes, or to reform

government and contract out aspects of government supply that could be taken up by private

firms operating in the competitive marketplace (Osborne and Gaebler 1993). Where efforts to

reform government have been thorough-going, an interesting dynamic has developed. As the

core public sector has shrunk in size, the number of policy analysts employed in the sector has

increased, both in relative and in absolute terms. This dynamic is indicative of governments devel-

oping their capacities in the management of contracts rather than in the management of services

(Savas 1987). In these new environments, people exhibiting skills in mechanism design and

benefit-cost analysis have been in demand. Therefore, employment opportunities for policy ana-

lysts have tended to expand, even as the scope of government has been curtailed. Fiscal con-

servatism, which was a hallmark of governments in many jurisdictions that embraced the New

Public Management practices added to this trend (Yergin and Stanislaw 1998; Williamson 1993).

When budgets are squeezed, it becomes critical for all possible efficiency gains to be realized.

More than any other trained professionals, policy analysts working in government are well-

placed to undertake the kind of analytical work needed to identify cost-saving measures and to

persuade elected decision-makers to adopt them.

The exact influence policy advisors have been able to exert over political decision-makers is

difficult to measure because of the range of factors that influence policy outcomes. Moreover,

the changing nature of political and institutional environments throughout periods in history

have meant that not only has the definition of policy analyst changed over time but the extent

of their influence has also fluctuated. ‘Windows of opportunity’ for policy influence appear

more frequently in some circumstances than in others (Kingdon 1995). For example, the move

towards addressing large national debts led to wide-scale reform of government policy settings

in many jurisdictions during the 1980s and 1990s.

By the 1980s the world had become intensely global: economically, socially and politically.

Global problems often resulted in similar policy outcomes. In New Zealand at that time, poli-

tical leaders became aware that the country’s economic position was deteriorating. Faced with

economic stagnation, social disruption and ideological shifts away from dependence upon gov-

ernment for the allocation of many resources in society, the New Zealand government became

open to the influence of institutions and agencies with perceived expertise in the dominant

problems of the day (Oliver 1989).

The strength of central agencies, endowed with economic expertise, such as the New Zealand

Treasury and organizations such as the New Zealand Business Round Table (NZBRT), were

Public policy debate

7

intensified by individual networks intertwining ministers with key bureaucrats and non-elected

political actors. Not unlike other countries such as Norway, Sweden, Britain and France, in the

1980s, a single economics ministry in New Zealand meant that there were few opportunities

for countervailing power. The system in New Zealand at that time was thus described by one

commentator as an ‘elective dictatorship’ (Boston 1989).

In New Zealand the Treasury was the Government’s most important advisory body. By

recruiting a senior manager from the Treasury, Roger Kerr, to lead the NZBRT in 1986,

business leaders recognized the value of networks and the strength of the Treasury department

(Mintrom 2006). The NZBRT ensured that the views of business leaders were fully articulated

in policy discussions. The Minister of Finance was reported at the time to have a relationship

with the Round Table that was ‘so close you couldn’t slide a Treasury paper between them’

(Murray and Pacheco 2001).

The conditions that allowed a few advisors broad influence over political decision-makers can

partly explain why the economic restructuring undertaken in New Zealand in the 1980s and

1990s was so extensive. As with ‘Reaganism’ in the United States, and at least the early days of

‘Thatcherism’ in Britain, ‘Rogernomics’ in New Zealand followed a pattern of international

policy transfer which included commercialization, liberalization and deregulation. These ideas

were not new. They began in North America and Europe a decade earlier and ‘represented a

global spread of neo-liberal politics’ (Dolowitz and Marsh 2000; Heffernan 1999).

Over the past few decades, technological advances have improved communication and made

it easier for policy advisers and decision-makers to assess different policy decisions, thus increasing

the occurrences of policy transfer. While it is relatively simple to spot broad trends in policy

development, individual countries always exhibit specific, even idiosyncratic, policy design ele-

ments. Liberalization in New Zealand, the United States and Britain during the 1980s and 1990s

included rescission of the existing regulatory regime and a reduction in protectionist legislation

aimed at instituting competitiveness through a free market. In New Zealand, it was carried out

extensively at an unprecedented speed and has largely been unparalleled (Goldfinch 1998). In

the United States the focus on monetary policy as a prime instrument to shape the economy

represented a comprehensive change in policies which were up to that time not politically

viable. In contrast, liberalization and deregulation in Britain were not as quick, nor were they a

radical departure from ideas already in train, and were thus seen as more path dependant and

incremental (Niskanen 1988; Heffernan 1999).

The global financial crisis emerged rapidly in mid-2007. This saw governments around the

world intervene in the operation of financial markets in a manner that would have been

shunned during the 1980s and 1990s. The degree to which public policy settings undergird the

effective workings of markets has become salient again. As a consequence, the current period

has entrenched the pervasive role of government in capitalist societies. At its best, this new era

of policy-making has seen efforts being made to carefully balance responses to market failures

against risks of government failure. At its worst, the new era has offered instances of those who

contributed to the crisis being cushioned, with those most harmed by the crisis receiving no

governmental relief. In short, the current period has opened space for extensive debate about

public policy and the role of government in society. The developmental role of governments in

promoting economic advancement – observed most starkly in the Asian tiger economies over

recent decades – has been eyed by some observers as a sound prescription, even for the most

advanced economies in the world. Sceptics have been much more concerned about extensive

government interventions into economic activities. Frequent voice has been given to the worry

of government failure – exhibited most obviously by special interest capture of government

subsidies.

Mintrom and Williams

8

Discussions during the 1960s and 1970s of the role of policy analysts in society often por-

trayed them as ‘whiz kids’ or ‘econocrats’ on a quest to imbue public decision-making with

high degrees of rigour and rationality (Self 1977; Stevens 1993). Certainly, proponents of benefit-

cost analysis considered themselves to have a technique for assessing the relative merits of

alternative policy proposals that, on theoretical grounds, trumped any others on offer. Likewise,

proponents of programme evaluation employing quasi-experimental research designs considered

their approach to be superior to other approaches that might be used to determine programme

effectiveness (Cook and Campbell 1979). That the application of both benefit-cost analysis and

quantitative evaluation techniques has continued unabated for several decades speaks to their

perceived value for generating usable knowledge. However, the limitations of such techniques

have not been lost on critics. In the case of benefit-cost analysis, features of the technique that

make it so appealing – such as the reduction of all impacts to a common metric and the cal-

culation of net social benefits – have also attracted criticism. In response, alternative methods for

assessing the impacts of new policies, such as environmental impact assessments, social impact

assessments and health impact assessments have gained currency (Barrow 2000; Lock 2000; Wood

1995). Similarly, widespread efforts have been made to promote the integration of gender and

race analysis into policy development (Mintrom 2012; Myers 2002; True and Mintrom 2001).

In the case of evaluation studies, fundamental and drawn-out debates have occurred covering

the validity of various research methods and the appropriate scope and purpose of evaluation

efforts. Significantly for the present discussion, these debates have actually served to expand demand

for policy analysis. Indeed, government agencies designed especially to audit the impacts of

policies on the family, children, women and racial minorities have now been established in

many jurisdictions. Further, evaluation of organizational processes, which often scrutinize the

nature of the interactions between organizations and their clients are now accorded equivalent

status among evaluators as more traditional efforts to measure programme outcomes (Patton

1997; Weiss 1998). Yet these process evaluations are motivated by very different questions and

draw upon very different methodologies than traditional evaluation studies that assessed programme

impacts narrowly.

This review of the evolving demand for policy analysis has identified several trends that have

served both to embed policy analysts at the core of government operations and to expand

demand for policy analysts both inside and outside government. These trends have much to do

with the growing complexity of economic and social relations and knowledge generation. Yet

there is also a sense in which policy analysis itself generates demand for more policy analysis.

While these trends have been most observable in national capitals, where a large amount of

policy development occurs, they have played out in related ways in other venues as well. For

instance, in federal systems, expanding cadres of well-trained policy analysts have become engaged

in sophisticated, evidence-based policy debates in state and provincial capitals.

Cities, too, are increasingly making extensive use of policy analysts in their strategy and planning

departments. At the global level, key coordinating organizations, such as the World Bank, the

International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization, and the Organization for Eco-

nomic Cooperation and Development have made extensive use of the skills of policy analysts to

monitor various transnational developments and national-level activities of particular relevance

and interest.

Today, the demand for policy analysis is considerable, and it comes both from inside and

outside governments. This demand is likely to keep growing as calls emerge for governments to

tackle emerging, unfamiliar problems. On the one hand, we should expect to see ongoing

efforts to harness technical procedures drawn from the social sciences and natural sciences for

the purposes of improving the quality of policy analysis. On the other hand, more people are

Public policy debate

9

likely to apply these techniques, reinvent them, or develop whole new approaches to counteract

them, all with the purpose of gaining greater voice in policy-making at all levels of government

from the local to the global.

The evolving supply of policy analysis

To meet the growing demand for policy analysis, since the mid-1960s supply has greatly

expanded. But this expansion has been accompanied, at least around the edges of the enterprise,

by a transformation in the very nature of the products on offer. Consequently it is now com-

monplace to find policy analysts who question the questions of the past, who are politically

motivated, or who seek to satisfy intellectual curiosity rather than to offer solutions to immediate

problems. Thus, the apparently straightforward question of what constitutes policy analysis cannot

be addressed in a straightforward manner. Answers given will be highly contingent on context.

For example, an answer offered in the mid-1970s would be narrower in scope than an answer

offered now. Likewise, the question of who produces policy analysis is also contingent. Econ-

omists have always been well represented in the ranks of policy analysts. People from other

disciplines have also contributed to policy analysis, although there has often been a sense that

other disciplines have less to contribute to policy design and the weighing of alternatives.

Today, practitioners and scholars heralding from an array of disciplines are engaged in this kind

of work, and the relevance of disciplines other than economics is well understood. In this review

of the evolving supply of policy analysis, we consider both the development of a mainstream

and the growing diversity of work that now constitutes policy analysis.

There has always been a mainstream style of conducting policy analysis. That style is more

prevalent today than it has ever been. The style is portrayed by practitioners and critics alike as

the application of a basic, yet continually expanding, set of technical practices (Stokey and

Zeckhauser 1978). Most of those practices derive from microeconomic analysis. They include

the analysis of individual choice and trade-offs, the analysis of markets and market failure, and the

application of benefit-cost analysis. Contemporary policy analysis textbooks tend to build on this

notion of policy analysis as a technical exercise (Bardach 2000; Mintrom 2012; Munger 2000;

Weimer and Vining 2005). For example, in his practical guide to policy analysis, Eugene Bar-

dach (2000) contends that a basic, ‘eightfold’ approach can be applied to analysing most policy

problems. The approach requires us to define the problem, assemble some evidence, construct the

alternatives, select the criteria, project the outcomes, confront the trade-offs, decide, and tell our

story. As with Stokey and Zeckhauser’s approach, Bardach’s approach clearly derives from

microeconomic analysis, and benefit-cost analysis in particular. None of this should surprise us

since, to the extent that a discipline called policy analysis exists at all, it is a discipline that grew

directly out of microeconomic analysis. That disciplinary linkage remains strong. Economists

comprise the majority of members of the United States-based Association for Public Policy Analysis

and Management (APPAM), the largest such association in the world. Likewise, contributions

to the Association’s Journal of Policy Analysis and Management are authored predominantly,

although certainly not exclusively, by economists.

Viewed positively, we might note that the basic approach to policy analysis derived from

microeconomics is extremely serviceable. As scholars have continued to apply and expand this

style of analysis, a rich body of technical practices has been created. Extensive efforts have been

made to ensure that university students interested in careers in policy analysis gain appropriate

exposure to these approaches and receive opportunities to apply them. Most Masters pro-

grammes in public policy analysis or public administration require students to take a core set of

courses that expose them to microeconomic analysis, public economics, benefit-cost analysis,

Mintrom and Williams

10

descriptive and inferential statistics, and evaluation methods. Sometimes the core is augmented

by courses on topics such as strategic decision-making, the nature of the policy process, and

organizational behaviour. Students are usually also given opportunities to augment their core

course selections with a range of elective courses from several disciplines. Without doubt, gradu-

ates of these programmes emerge well-equipped to immediately begin contributing in useful

ways to the development of public policy. Over recent decades, many universities in the United

States have introduced Masters programmes designed to train policy analysts along the lines

suggested here. More recently, similar programmes have been established in many other coun-

tries around the globe. Those establishing them know that there is strong demand for the kind

of training they seek to provide. These professional courses create opportunities for people who

have already been trained in other disciplines to acquire valuable skills for supporting the devel-

opment of policy analyses. Graduates end up being placed in many organizations in the public,

private and non-profit sectors.

Viewed more negatively, the mainstream approach to teaching and practising policy analysis

can be critiqued for its narrowness and the privileging of techniques derived from economic

theory over analytical approaches that draw upon political and social theory. Suppose we again

describe the policy-making process as a series of stages: problem definition; agenda setting; policy

adoption; implementation; and evaluation. The mainstream approach to policy analysis has little

to contribute to our understanding of agenda setting, or the politics of policy adoption, imple-

mentation and evaluation. Steeped as it is in the rational choice or utilitarian perspective, main-

stream policy analysis is poorly suited to helping us to understand why particular problems

might manifest themselves at given times, why some policy alternatives might appear politically

palatable while others will not, and why adopted policies often go through significant trans-

formations during the implementation stage. In addition, technical approaches to programme

evaluation, while obviously necessary for guiding the measurement of programme effectiveness,

typically prescribe narrow data collection procedures that can leave highly relevant information

unexamined. Studies that dwell on assessing programme outcomes are unlikely to reveal the

multiple, and perhaps conflicting, ways that programme personnel and programme participants

often make sense of programmes. In turn, this might cause analysts to misinterpret the motiva-

tions that lead programme personnel and participants to redefine programme goals from those

originally intended by policy-makers. Problems of programme design or programme theory

might end up being ignored in favour of interpretations that place the blame on faulty imple-

mentation (Chen 1990). More generally, mainstream approaches to policy analysis can encou-

rage practitioners to hold tightly to assumptions about individual and collective behaviour that

are contradicted by the evidence. In the worst cases, this can lead to inappropriate specification

of proposals for policy change.

The foregoing observations might cause us to worry that mainstream training in policy ana-

lysis does not sufficiently equip junior analysts to become reflective practitioners or practitioners

who listen closely to the voices of people who are most likely to be affected by policy change

(Forrester 1999; Schön 1983). Certainly, strong critiques of mainstream analytical approaches

have led to some rethinking of the questions that policy analysts should ask when working on

policy problems (Stone 2002). Yet it is a fact that many people who have gone on to become

excellent policy managers and leaders of government agencies began their careers as junior

policy analysts fresh out of mainstream policy programmes. This suggests that, within profes-

sional settings, heavy reliance is placed on mechanisms of tacit knowledge transfer, whereby

narrowly trained junior analysts come to acquire skills and insight that serve them well as policy

managers. Our sense is that the key components of this professional socialization can be codified

and are teachable (Mintrom 2003). But much of what it takes to be an effective policy analyst is

Public policy debate

11

not captured in the curricula of the many university programmes that now exist to train future

practitioners.

Beyond mainstream efforts to expand the supply of policy analysts, all of which place heavy

emphasis on the development of technical skills informed primarily by microeconomic theory,

other disciplines also contribute in significant ways to the preparation of people who eventually

become engaged in policy analysis. In these cases, the pathway from formal study to the practice

of policy analysis is often circuitous. People with substantive training in law, engineering, natural

sciences and the liberal arts might begin their careers in closely related fields, only to migrate

into policy work later. For example, individuals trained initially as sociologists might gain pro-

fessional qualifications as social workers and, after years in the field, assume managerial roles that

require them to devote most of their energies to policy development. People pursuing these

alternative professional routes towards working as policy analysts can bring rich experiences and

diverse insights to policy discussions. The resulting multidisciplinary contributions to policy

discussions have been known to generate their share of intractable policy controversies (Schön

and Rein 1994). Yet, when disagreements that emerge from differences in training and analy-

tical perspectives are well managed, these multidisciplinary forums can produce effective policy

design. Indeed, increasing efforts are now being made to address significant problems through

‘joined-up government’ initiatives (Perri 6: 2004). Through these, individuals with diverse profes-

sional backgrounds who are known to have been working on similar problems are brought

together to work out cohesive policy strategies to address those problems. For example, pedia-

tricians, police officers, social workers and educators might be asked to work together to devise

policies for effective detection and prevention of child abuse.

Two somewhat contradictory trends in the evolving supply of policy analysis have been noted

here. On the one hand, the growth of university-based professional programmes designed to

train policy analysts has contributed to a significant degree of analytical isomorphism. No matter

which university or country such programmes are based, the students are required to study

much the same set of topics and to read from a growing canon of articles and books covering

aspects of policy analysis. These programmes promote ways of thinking about public policy that

owe heavy debts to the discipline of economics. On the other hand, researchers and practi-

tioners working out of other disciplines have increasingly become involved in the production of