The State of Tennessee’s Jails

John G. Morgan

Comptroller of the Treasury

Office of Research

State of Tennessee

August 2003

STATE OF TENNESSEE

John G. Morgan COMPTROLLER OF THE TREASURY

Comptroller

STATE CAPITOL

NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE 37243-0264

PHONE (615) 741-2501

August 29, 2003

The Honorable John S. Wilder

Speaker of the Senate

The Honorable Jimmy Naifeh

Speaker of the House of Representatives

and

Members of the General Assembly

State Capitol

Nashville, Tennessee 37243

Ladies and Gentlemen:

Transmitted herewith is a report prepared by the Office of Research concerning

conditions in Tennessee county jails. The study analyzes overcrowding, jail

inspections, and jail funding, and provides recommendations for consideration.

Comptroller of the Treasury, Office of Research. Authorization Number 307308, 600 copies,

August 2003. This public document was promulgated at a cost of $2.20 per copy.

The State of Tennessee’s Jails

Margaret Rose

Senior Legislative Research Analyst

and

Brian Doss

Associate Legislative Research Analyst

Ethel R. Detch, Director

Douglas Wright, Assistant Director

Office of Research

505 Deaderick Street, Suite 1700

Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0268

615/401-7911

www.comptroller.state.tn.us/orea/reports

John G. Morgan

Comptroller of the Treasury

August 2003

i

Executive Summary

Over the past several decades, courts have found that conditions of confinement in many

U.S. jails violate constitutional rights contained in the Eighth Amendment (banning cruel

and unusual punishment) and the Fourteenth Amendment (which guarantees due process

rights). In some cases, including in Tennessee, courts have ordered counties to make

extensive changes, costing extraordinary amounts, to deal with matters such as medical

care, staffing, overcrowding, sanitation, religion, nutrition, recreation, safety, and

security.

Although state law gives sheriffs responsibility to manage county jails, some state

agencies impact their operations—most frequently, the Tennessee Corrections Institute,

the Department of Correction, and the Department of Mental Health and Developmental

Disabilities. The Tennessee Corrections Institute inspects jails; the Department of

Correction holds some state inmates in jails; and the Department of Mental Health and

Developmental Disabilities is responsible for serving inmates with mental illnesses.

This report concludes:

Many Tennessee jails are overcrowded. Overcrowding presents many implications for

governments. It strains county and state budgets and severely limits a facility’s capacity

to provide adequate safety, medical care, food service, recreation, and sanitation. The

total number of inmates in Tennessee’s jails increased 56 percent, from 13,098 in fiscal

year 1991-92 to 20,393 in fiscal year 2002-03. Local jails held an average of 2,301

Department of Correction inmates awaiting transfer to state prisons during FY02-03.

By June 2003, the department had 1,956 inmates awaiting transfer.

During fiscal year 2000-01, 47 Tennessee county facilities operated at an average

capacity of 100 percent or greater and 12 operated at an average capacity of 90-99

percent. The number operating at 100 percent or greater rose to 60 in fiscal year 2001-02,

and declined to nine operating at an average capacity of 90-99 percent.

A National Institute of Corrections publication states that jail crowding is a criminal

justice system (emphasis added) issue, and its roots lie with decisions made by officials

outside the jail, such as police, judges, prosecutors, and probation officers. Like some

other communities, Shelby and Davidson Counties have created criminal justice

coordination committees to examine jail crowding and other criminal justice issues. The

committees provide a forum for key justice system professionals (such as law

enforcement officials, judges, prosecutors, and public defenders) and other government

officials to discuss justice system challenges. Committees analyze the implications that

individual agency decisions impose on the entire criminal justice system. (See pages 7-

10.)

Tennessee’s continuing failure to provide adequate capacity in state prisons has

contributed to overcrowding in some jails. Tennessee statutes address only state

prison overcrowding, but offer no contingencies for overcrowded local jails. Inmate

lawsuits against Tennessee resulted in several pieces of legislation that allowed the state

to respond to prison overcrowding. These laws specify that the governor can declare a

state of overcrowding under certain conditions and may direct the Commissioner of

ii

Correction to notify all state judges and sheriffs to hold certain inmates until state

facilities have lowered their population to 90 percent of capacity. The department has

operated under this statute continuously since the 1980s. (See pages 10-11.)

Tennessee statutes governing the transfer of state prisoners from county jails

conflict with each other. T.C.A. 41-8-106 (g) requires the department to take into its

custody all convicted felons within 14 days of receiving sentencing documents from the

court of counties not under contract with the County Correctional Incentives Program. On

the other hand, T.C.A. 41-1-504 (a)(2) allows the department to delay transfer of felons

who had been released on bail prior to conviction for up to 60 days until prison capacity

drops to 90 percent.

In 1989, Hamilton, Davidson, Knox, and Madison Counties sued the state for shifting its

overcrowding burden onto their facilities. A federal court placed certain limits on the

number of inmates that each of those jails could hold. The Department of Correction

takes inmates from those facilities before those from other jails when transferring inmates

to state facilities. (See pages 11-12.)

In spite of T.C.A. 41-4-141, which allows two or more counties to jointly operate a

jail, no Tennessee counties have done so. As a result, some counties miss the

opportunity to save county funds and to lower their liability risks. A regional jail is

defined as a correctional facility in which two or more jurisdictions administer, operate,

and finance the capital and operating costs of the facility. (See page 12.)

Comptroller’s staff observed unsafe and unsanitary conditions in some of the jails

visited during this study. Comptroller’s staff visited 11 jails during this study. Staff

selected rural, urban, and medium sized counties in all three grand divisions of the state.

Additionally, staff chose some counties recommended as model facilities and others

described as substandard. Two of the jails were new with no visible problems. In others,

however, research staff observed conditions that pose danger or violate standards. (See

pages 13.)

The Tennessee Corrections Institute has no power to enforce its standards, resulting

in conditions that endanger inmates, staff, and the public. In 2002, 25 county jails

failed to meet certification standards. Without sanctions, counties often fail to correct

conditions that may be dangerous and likely to result in costly lawsuits. Several other

states impose an array of sanctions for facilities that do not meet standards. In 2001 the

General Assembly considered, but did not pass, a bill that would have given TCI more

enforcement authority. House Bill 398/Senate Bill 764 would have allowed TCI to:

• issue provisional certifications;

• decertify facilities;

• exclude counties from participating in the County Correctional Incentives Act of

1981; and

• ask the Attorney General and Reporter to petition circuit courts to prohibit

inmates from being confined in facilities that do not meet standards or impose

threats to the health or safety of inmates.

iii

At least 53 sheriffs report that inmates have sued their facilities in the last five calendar

years, but that most suits are frivolous and eventually dismissed. As of calendar year

2001, at least nine jails are under a court order or consent decree. (See pages 13-14.)

TCI continues to certify inadequate and overcrowded jails that do not meet state

standards. State law prohibits TCI from decertifying deficient facilities if the county

submits a plan within 60 days of the initial inspection to correct deficiencies related to

square footage and or/showers and toilets as well as jail capacity. Many counties delay

implementing their plans indefinitely, yet TCI continues to certify the facilities. (See

pages 14-15.)

TCI standards do not appear to meet the level of quality mandated by T.C.A. 41-4-

140. The law requires that TCI standards approximate, as closely as possible, those

standards established by the inspector of jails, federal bureau of prisons, and the

American Correctional Association. However, TCI standards are minimal and are not as

comprehensive as those of the American Correctional Association. TCI omits ACA

standards dealing with monthly fire and safety inspections, prerelease programs,

population projections, staffing patterns, and administrators’ qualifications. (See page

15.)

TCI has not developed minimum qualification standards for local correctional

officers and jail administrators. Few local correctional officer positions are civil

service. Newly elected sheriffs usually hire new officers. TCI standards require that

correctional officers receive 40 hours of basic training within the first year of

employment. According to several jail administrators and sheriffs, newly hired

correctional officers frequently report on their first day with no experience or training on

how to perform their duties or handle unruly inmates and emergencies. (See pages 15-

16.)

The Tennessee Corrections Institute appears to have inadequate staff to fulfill its

mandate. TCI reduced its staff from 26 positions in 1982 to 11 positions in 2002 because

of forced budget cuts. The agency’s staff now consists of only six inspectors, an

executive director, and clerical staff. The six inspectors must cover all 95 county jails,

nine county jail annexes, 14 city jails, and eight correctional work centers. The lack of

staff contributes to conditions that negatively affect the quality of jail inspections.

The six inspectors provide training and technical assistance to jail staff as well as

conducting inspections. Mixing regulatory and assistance functions can result in a lack of

objectivity by inspectors. (See pages 16-17.)

TCI inspection practices appear inadequate to ensure safe and secure jails. Office of

Research staff observed several problems with TCI’s inspection practices during jail

inspections, including differences in interpreting standards, timing of inspections,

assigning inspectors, and quality of inspections.

Although TCI inspections are unannounced, they generally occur within the same or an

adjacent month of the previous year’s inspection. As a result, jail staff can anticipate

inspections and present themselves in ways during the inspections that do not reflect their

normal routines and practices. (See pages 17-18.)

iv

TCI inspectors provide minimal training to correctional officers (jailers), who must

attend 40 hours of basic training during their first year of employment. TCI

provides no training to sheriffs and jail administrators. As a result, some correctional

officers begin work with no preparation and, in fact, may never receive training,

increasing the potential of liability. Training is critical to protect both inmates and

correctional officers. Newly elected sheriffs without previous law enforcement

certification must attend training provided by the Peace Officers Standards and Training

Commission. However, most of this training relates to law enforcement activities, with

little time devoted to jail management. (See pages 18-19.)

The state does not evaluate the reimbursement process for housing state inmates in

local correctional facilities as required by T.C.A. 41-1-405, enacted in 1983. Although

the various reports submitted by counties to determine reimbursements are reviewed, the

overall reimbursement process is not continually evaluated. The statute explains the

General Assembly’s intent: “a continuing evaluation of the impact of the state correction

system upon local correction systems is essential to determine the method and amount of

assistance, financial or otherwise, necessary to equitably compensate such local systems

for their continuing role in the overall correction system of this state.” The statute

suggests that a “task force composed of all facets of the criminal justice system” conduct

the evaluation. Because the process has not been continually reviewed the current method

may not comply with the General Assembly’s intent to equitably compensate local

correctional systems. Any evaluation should include an analysis of marginal and fixed

costs which can help to determine if the reimbursement process is equitable to the

counties and the state. (See pages 19-20.)

Low funding for jails contributes to unsafe facilities, high correctional officer

turnover, and staff shortages in some jails. Most sheriffs interviewed by Office of

Research staff noted strained relationships with county executives and county

commissions regarding jail funding. The sheriffs believe that these county officials have

other budgetary priorities and do not fully appreciate the liability issues caused by

underbudgeting. Inadequate funding usually leads to unsafe conditions, including critical

understaffing or physical plant deterioration that endangers inmates and jail personnel.

Most sheriffs report a high correctional officer turnover rate because of low salaries. (See

pages 20-21.)

No state agency enforces or monitors compliance with T.C.A. 41-8-107 (c), which

requires non-certified facilities to use 75 percent of the state reimbursement to

improve correctional programs or facilities. These facilities may remain in poor and

uncertifiable conditions. In FY 2001-02, DOC paid $3,515,426 to county jails that were

not certified; 75 percent of this amount is $2,636,569. (See page 22.)

The Criminal Justice/Mental Health Liaison program helps divert inmates with

mental illnesses from jail in specific areas of the state. Statewide, however,

Tennessee continues to lack adequate community services and institutional

placements for inmates with mental illnesses held in jail. Both mental health

professionals and sheriffs agree that some inmates with mental illnesses would be better

served by community resources than by placing them in jails for minor offenses possibly

v

caused by manifestations of their illnesses. Other offenders may need the treatment

environment of a mental health facility. In at least one case, a Davidson County judge

ruled that the right to a speedy trial for an inmate with a mental illness had been violated

after the inmate spent over a year in jail awaiting a competency hearing.

In an attempt to relieve jails housing inmates who need treatment in mental health

institutes, Public Chapter 730 of 2002 specifies that the Commissioner of Mental Health

and Developmental Disabilities (DMHDD) must exert all reasonable efforts to admit

such an inmate within five days of receiving a commitment order.

The Department of Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities (DMHDD) established

a Criminal Justice/Mental Health Liaison pilot project to improve communication and

coordination among the community, the criminal justice system, and the mental health

system, and to establish diversion activities. Although the liaison program is too new to

determine the impact of its criminal justice activities, many jail staff told researchers that

the program is an asset. (See pages 22-24.)

Office of Research staff were unable to determine whether sheriffs comply with

federal and state special education mandates. In 2003, the Department of Education

sent a copy of the department’s Policy and Procedure for Incarcerated Children with

Disabilities to all county sheriffs and local education agencies (LEAs). State policies and

procedures follow the directives of the federal law. The policy applies to all students with

disabilities, who are legally mandated to receive an education in Tennessee through their

22

nd

birthday. Most sheriffs and jail administrators denied that they hold inmates who are

eligible for special education services. However, most smaller jails do not use a

classification system to identify eligible inmates. Thus, some eligible students may not

receive services to which they are entitled. Providing special education programming

could help such inmates as well as protect jail staff from suits for failing to ensure that

they identify such children. (See pages 24-25.)

Most jails do not help inmates access social or health services upon release. Most

jails do not offer help to inmates to prepare them to reenter society, often resulting in

inmates who are unprepared for the challenges they encounter. On the other hand,

Davidson County officials are committed to assisting inmates scheduled for release to

help them avoid reincarceration. Officials expressed concerns about inmates being

disenrolled from TennCare upon incarceration and the difficulties in reenrolling them

upon release. They also believe that the Department of Human Services should be more

involved in assisting released inmates to access its services, such as food stamps, TANF,

or vocational rehabilitation. An American Correctional Association standard recommends

prerelease planning.

An ACA non-mandatory standard suggests facilities adopt a written policy, procedure,

and practice to provide continuity of care from admission to discharge from the facility,

including referral to community care. Some criminal justice and mental health

professionals expressed concern that inmates with mental illnesses receive services in

jails, but upon release, are not always linked to community resources to provide

continued services. Because of a potential lapse in services, these same persons may

return to the criminal justice system. (See page 25.)

vi

Recommendations begin on page 26.

Legislative Recommendations

• The General Assembly may wish to authorize the Tennessee Corrections Institute

to ask the state’s Attorney General and Reporter to petition circuit courts to close

jails that fail to correct unsafe conditions.

• The General Assembly may wish to enact legislation prohibiting state prisoners

from being held in facilities that are not certified by TCI because of safety issues.

• The General Assembly may wish to clarify statutory language regarding the

transfer of state prisoners from county jails.

• The Select Oversight Committee on Corrections may wish to review the current

process to reimburse local governments for housing state inmates in local

correctional facilities.

Administrative Recommendations

• Local governments should establish ongoing avenues of communication such as

councils or committees composed of criminal justice agencies to seek solutions to

problems such as overcrowding.

• The Department of Correction should make every effort to transfer state inmates

held in non-certified jails as quickly as possible

• The Department of Correction should not contract with overcrowded jails to hold

state inmates.

• Some Tennessee counties should consider the feasibility of establishing regional

jails.

• The Tennessee Corrections Institute should review its standards and inspection

practices annually, revising them as needed to adequately protect jails from

liability.

• The Tennessee Corrections Institute should provide training to sheriffs, jail

administrators, and other supervisory personnel.

• The Tennessee Corrections Institute should request reinstatement of the positions

it lost because of budget reductions in the 1980s and 1990s.

• The Tennessee Corrections Institute should establish two distinct divisions within

the agency – one for inspections and the other for training and technical assistance

because mixing regulatory and assistance functions can reduce inspectors’

objectivity.

vii

• The Tennessee Corrections Institute should vary its inspection cycle and rotate

inspector assignments from year to year.

• The state should enforce the statute requiring counties with noncertified jails to

use 75 percent of their DOC reimbursements to improve correctional programs

and facilities.

• The Department of Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities should

determine the impact of its criminal justice activities in local jails. If warranted,

DMHDD should seek additional federal funds to expand the Mental Health

Liaison Program statewide and increase the availability of mobile crisis teams.

• The Department of Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities should

prioritize bed space to ensure that inmates awaiting competency hearings are

evaluated in a timely manner.

• Sheriffs and jail administrators should provide discharge planning for inmates

with mental illnesses who need continued care upon release.

• Sheriffs and jail administrators should report all inmates who may be eligible for

special education services to the LEA.

• State agencies such as the Bureau of TennCare and the Department of Human

Services should work more closely with jail personnel to reinstate benefits

inmates lose while incarcerated.

Agency responses to this report are in Appendices G-J.

Table of Contents

Introduction..........................................................................................................................1

Objectives ................................................................................................................1

Methodology............................................................................................................2

Why examine conditions in local jails? ..................................................................2

Background..............................................................................................................4

Analysis and Conclusions....................................................................................................7

Overcrowded Jails....................................................................................................7

Jail Conditions, Standards, Inspections, and Training...........................................13

Conditions........................................................................................................13

Standards..........................................................................................................13

Inspections .......................................................................................................16

Training............................................................................................................18

Jail Funding............................................................................................................19

Mental Illness, Special Education, and Post-Release Issues..................................22

Recommendations..............................................................................................................26

Legislative..............................................................................................................26

Administrative........................................................................................................26

Appendices.........................................................................................................................29

Appendix A: Office of Research Jail Survey.........................................................29

Appendix B: County Jails Not Certified in 2002 by TCI ......................................35

Appendix C: Average Total Population and Average Total Rated Beds of

Tennessee Local Correctional Facilities during FY 2001 and FY 2002................36

Appendix D: Rates Paid by the Tennessee Department of Correction To House

State Inmates in Local Facilities in Fiscal Year 2001............................................39

Appendix E: Amount Paid by TDOC to House State Inmates in

Non-Certified Facilities .........................................................................................41

Appendix F: Criminal Justice/Mental Health Liaisons..........................................42

Appendix G: Response from the Tennessee Department of Correction................43

Appendix H: Response from the Tennessee Corrections Institute ........................44

Appendix I: Response from the Tennessee Department of Education ..................47

Appendix J: Response from the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and

Developmental Disabilities....................................................................................49

Appendix K: Persons Interviewed .........................................................................51

1

If the public, through its judicial and penal system, finds it necessary to

incarcerate a person, basic concepts of decency, as well as reasonable respect

for constitutional rights, require that he be provided a bed.

Judge William P. Gray

Stewart v. Gates, 1978

1

Introduction

Contrary to Judge Gray’s opinion, some Tennessee jails are unable to furnish a bed for each

inmate. Overcrowding is only one issue that places some Tennessee counties at risk of lawsuit by

inmates.

Over the past several decades, courts have found that conditions of confinement in many U.S.

jails violate constitutional rights contained in the Eighth Amendment (banning cruel and unusual

punishment) and the Fourteenth Amendment (which guarantees due process rights). In some

cases, including in Tennessee, courts have ordered counties to make extensive changes, costing

extraordinary amounts, to address medical care, staffing, overcrowding, sanitation, religion,

nutrition, recreation, safety, and security.

The Tennessee Constitution requires each county to elect a sheriff and other officials, whose

qualifications and duties are determined by the General Assembly.

2

T.C.A. 41-4-101 places

sheriffs in charge of county jails and all their prisoners. The sheriff may appoint a jailer, but the

sheriff is civilly responsible for the jailer’s acts. Tennessee jails hold inmates who:

• have been committed for trial for public offenses,

• have been sentenced to a penitentiary, but await transfer to the prison,

• have been committed for contempt or on civil process,

• have been committed for failure to give security for their appearances as witnesses in

criminal cases,

• have been charged with or convicted of criminal offenses against the United States,

• are awaiting transfer to a mental health facility, or

• have otherwise been committed by authority of law.

3

Objectives

The Office of Research undertook this study with the following objectives:

• to determine the nature and extent of conditions in Tennessee jails that leave counties at

risk of lawsuits;

• to determine risks these conditions pose to inmates and the public;

• to determine the extent that state practices contribute to such conditions;

• to determine whether county jails have adequate funding to provide sufficient staff,

essential inmate services, and safety precautions; and

• to examine best practices shown to protect both inmates and the public.

1

Wayne N. Welsh, Counties in Court, Temple University Press, 1995, p. 3.

2

Constitution of the State of Tennessee, Article VII, Section 1.

3

T.C.A. 41-4-103.

2

Methodology

The conclusions reached and recommendations made in this report are based on the following:

• review of state statutes related to county jails,

• interviews with state officials, including the Tennessee Corrections Institute (TCI),

the Department of Correction (DOC), the Department of Mental Health and

Developmental Disabilities (DMHDD), and the Tennessee County Technical

Assistance Service (CTAS),

• interviews with selected sheriffs and jail administrators,

• interviews with others knowledgeable about jail conditions, including the American

Civil Liberties Union, a consultant to the Select Oversight Committee on Corrections,

and plaintiffs’ attorneys,

• on-site visits to selected jails,

• observations of selected jail inspections,

• review of jail standards and analysis of Tennessee Corrections Institute (TCI)

inspection reports,

• analysis of Department of Correction population projection reports,

• review of court settlements related to jail conditions, and

• review of various journals and newspaper articles.

In May 2002, researchers mailed surveys to 95 sheriffs responsible for 106 jails and workhouses

on the following issues:

• facility construction/expansion plans,

• facility beds and population,

• federal inmates,

• TCI certification,

• funding/budgets,

• staff issues,

• legal actions,

• inmate programs, and

• safety issues.

County officials returned 79 (75 percent) survey forms. A copy of the survey is in Appendix A.

Survey results are included throughout the analysis section of this report.

Why examine conditions in local jails?

The Office of Research staff undertook this study after reading numerous newspaper articles

highlighting problems in Tennessee’s jails. In some cases, the U.S. Department of Justice

investigated allegations of unconstitutional conditions. In addition, several local jails have been

involved in federal suits because of overcrowding and other safety issues. Shelby and Morgan

Counties have both been involved in long-term legal action because of safety issues. In some

cases, lawsuits may be more costly to counties than correcting the underlying conditions.

Tennessee Corrections Institute staff have the duty to inspect local correctional facilities and

recommend certification or non-certification to the TCI Board of Control. Facilities meeting all

TCI standards are certified. During calendar year 2002, TCI did not certify 25 county

correctional facilities.

3

Shelby County

The Shelby County Criminal Justice Center, which has not been certified since 1989, is under a

consent decree because of a suit, Darius D. Little vs. Shelby County, et al., stemming from

situations that include rape by gang members; absence of guards to assist inmate Little while he

was raped; rare presence of guards to observe inmates; overcrowding; failure to properly classify

inmates before deciding which inmates should be housed together; gang violence, such as

beatings and stabbings; and inmates posting orders and rules in the cell block that are imposed on

other inmates.

4

The court ordered the jail to classify inmates within 90 days of entry, never house inmates

classified as violent in a cell with more than one other inmate, assign a separate cell block officer

to each of the cell blocks in which inmates are incarcerated, and continuously observe inmates

directly.

5

Other Shelby County inmates filed suits for unconstitutional conditions, mostly because of

violent gang activity in the jail. In August 2000, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) notified

the county that it would investigate conditions pursuant to the Civil Rights of Institutionalized

Persons Act.

6

The allegations centered around:

• inadequate supervision of inmates;

• excessive levels of violence;

• inadequate mental health and medical care; and

• deficient sanitation and environmental health.

The DOJ toured the facility with expert consultants in prison security, correctional health care,

mental health care, and environmental health and safety. The investigation concluded that certain

jail conditions violated inmates’ constitutional rights. The investigation found:

• deficient security and supervision and protection from harm (e.g., inmate-on-inmate

violence; inmates not supervised adequately; failure to classify inmates effectively;

failure to discipline inmates who violate jail rules; failure to control dangerous

contraband, tools, or keys; and excessive use of force),

• constitutionally deficient mental health and medical care (e.g., deficient access to care;

deficient medication administration; inadequate suicide precautions; and medical safety

and related security concerns), and

• inadequate food, clothing, and shelter (e.g., unsafe food handling and food service;

inadequate pest control and sanitation; inadequate lighting, sanitation, and laundry

service in housing units; improper storage and handling of hazardous materials; deficient

4

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in Support of Order Granting Injunctive Relief to Remedy

Unconstitutional Conditions in the Shelby County Jail, Darius D. Little vs. Shelby County, et.al., Western District of

Tennessee, United States District Court, Civil Action No. 96-2520 TUA.

5

Order Granting Injunctive Relief to Remedy Unconstitutional Conditions in Shelby County Jail, Darius D. Little

vs. Shelby County, et.al., Western District of Tennessee, United States District Court, Civil Action No. 96-2520

TUA.

6

“The Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act,” U.S.C.A., Title 42, Chapter 21, Subchapter I-A, § 1997,

accessed July 27, 2001, http://www.ncd.gov/resources/cripa.html

.

4

fire safety and prevention; insufficient access to the courts; and insufficient access to

exercise.)

7

In August 2002, the DOJ announced an agreement to drop its lawsuit against Shelby County

because the county had initiated efforts to remedy deficiencies at the jail, especially related to

inmate supervision and revision of the jail’s policies and procedures.

8

Morgan County

The Justice Department had also filed suit against Morgan County for failing to maintain proper

living and health care standards. The DOJ and Morgan County subsequently entered a joint

motion for conditional dismissal of the suit in June 2000. The agreement required Morgan

County to:

• renovate or replace the jail to ensure adequate health, safety, and sanitation;

• construct an addition to contain cells and showers for women inmates a multipurpose

area for visitation, indoor recreation, and medical examinations;

• ensure compliance with life safety and fire protection codes;

• provide adequate staff and supervision;

• ensure that all jailers receive adequate training;

• allow inmates to be given exercise five days a week for one hour a day;

• provide adequate access to legal materials;

• provide medical and dental care;

• provide adequate mental health care;

• maintain the jail in a clean and safe physical condition and provide adequate clothing,

bedding, hygiene, and cleaning materials;

• ensure that inmates are not subject to unreasonable uses of force or chemical agents; and

• revise the jail manual to explicitly define and prohibit sexual misconduct and sexual

harassment.

9

The Morgan County sheriff indicates the suit has cost Morgan County in excess of $2 million.

10

Background

Although state law gives sheriffs responsibility to manage county jails, some state agencies

impact their operations—most frequently, the Tennessee Corrections Institute (TCI), the

Department of Correction (DOC), and the Department of Mental Health and Developmental

Disabilities (DMHDD.)

7

Letter from Department of Justice to Shelby County Mayor Jim Rout re Investigation of Shelby County Jail.

(accessed via web on August 28, 2001; accesses no longer available.)

8

News Release, U. S. Department of Justice, “Justice Department Reaches Agreement with Shelby County

Tennessee, Concerning Conditions of Confinement at Shelby County Jail,” August 12, 2002.

9

United States of America vs. Morgan County, Tennessee, et.al., Eastern District of Tennessee, United States

District Court, Civil Action No. 3:00 – CV 89.

10

Telephone conversation with Morgan County Sheriff, Bobby Clinton, October 16, 2002.

5

The General Assembly created the Tennessee Corrections Institute in 1974 to:

• train correctional personnel to deliver correctional services in state, municipal, county,

and metropolitan jurisdictions,

• evaluate correctional programs in state, municipal, county, and metropolitan jurisdictions,

and

• conduct studies and research in the area of corrections and criminal justice to make

recommendations to the Governor, the Commissioner of Correction, and the General

Assembly.

11

In 1980, the legislature gave TCI the additional responsibility to inspect all county and state

penal institutions, jails, workhouse detention facilities, or any other correctional facility.

12

The

1984 General Assembly removed TCI’s responsibility for inspecting state facilities and training

their staffs.

13

TCI staff inspect local correctional facilities using standards approved by the Board

of Control, the agency’s governing body. Staff recommend to the Board certification or non-

certification based on compliance or non-compliance. TCI staff told researchers that non-

certified facilities are likely less defensible in a lawsuit and could lose insurance coverage.

14

Exhibit 1 illustrates those counties with non-certified jails. A list of non-certified county jails is

in Appendix B. The 2002-03 budget for TCI is $691,500.

15

The Department of Correction pays local jails to house inmates for various reasons. In some

cases felons await transfer to penitentiaries to serve their sentences, but remain in local facilities

for extended periods because state facilities lack space. The Department of Correction also

contracts with some local jails to hold state prisoners to alleviate overcrowding in state facilities.

In other cases, judges sentence felons to serve their terms in county facilities. In FY 2002, DOC

paid $104,266,652 to 102 local facilities.

Sheriffs report that the number of local inmates with mental illnesses or disabilities and/or

substance abuse has increased. The Department of Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities

(MHDD) is responsible for court ordered forensic evaluations to determine a defendant’s

competency to stand trial and/or mental condition at the time of the offense. Regional Mental

Health Institutes, administered by DMHDD, serve pre-trial individuals from jails who meet

emergency involuntary commitment standards. Defendants ordered for forensic evaluations or

other pre-trial defendants are admitted without regard to bed availability upon meeting standards

for emergency involuntary commitment. DMHDD has created a diversion program with

community mental health centers to serve inmates in selected areas of the state.

16

In these

programs, criminal justice/mental health liaisons work to find alternative placements and

services for inmates with mental illnesses. The program’s budget is $770,000 ($294,000 in state

funds, and $476,000 in federal block grant funds).

17

In addition, mental health mobile crisis

teams conduct evaluations in jails, but responsiveness varies from team to team.

11

Public Chapter 733, Acts of 1974.

12

Public Chapter 913, Acts of 1980.

13

Public Chapter 938, Acts of 1984.

14

Interview with Roy Nixon, former Executive Director, Tennessee Corrections Institute, July 31, 2001.

15

TCI 2002-03 Budget.

16

Interview with Liz Ledbetter, Mental Health Specialist, Department of Mental Health and Developmental

Disabilities, July 26, 2002.

17

TDMHDD 2002-03 Budget.

6

Exhibit 1: County Jails Not Certified in 2002 by TCI

Source: Map created by Office of Research using Tennessee Corrections Institute Jail Inspection List.

Department of Education policy, in compliance with federal regulations, requires local education

agencies (LEAs) to provide special education services to eligible students, including those who

are incarcerated. The department has developed a procedure for sheriffs to identify affected

students and to notify the school system.

18

The director of special education for the Department

of Education indicated that the department does not have data on the number of special education

students served in county jails, but that it employs a staff person to monitor jails to ensure that

students with disabilities receive an appropriate education.

19

Special education criteria are found

at http://www.state.tn.us/education/speced/index.htm

18

Interview with Joe Fisher, Director of Special Education, Department of Education, August 26, 2002.

19

Email to Margaret Rose, Office of Research, from Joe Fisher, Director of Special Education, Department of

Education, Feb. 5, 2002.

7

Analysis and Conclusions

Overcrowded Jails

Many Tennessee jails are overcrowded. Overcrowding presents many implications for

governments. It strains county and state budgets and severely limits a facility’s capacity to

provide adequate safety, medical care, food service, recreation, and sanitation. In 1992, 27

percent of the nation’s large jails (those with 100 inmates or more) were under court order to

reduce overcrowding and/or improve general conditions of confinement.

20

• The number of inmates in Tennessee’s local correctional facilities increased 56 percent, from

13,098 in fiscal year 1991-92 to 20,393 in fiscal year 2002-03.

21

This increase is the result of

various factors, including:

o DOC inmates awaiting transfer to the penitentiaries

o some judges not allowing bail for pre-trial misdemeanants,

o some judges requiring sentenced misdemeanants to serve their full sentences,

o changes in law enforcement practices leading to more arrests,

o increase in the number of felons ordered to serve their sentences locally, and

o trial/hearing postponements.

• During fiscal year 2000-01, 47 Tennessee county facilities operated at an average capacity of

100 percent or greater, and 12 operated at an average capacity of 90-99 percent. The number

operating at 100 percent or greater rose to 60 in fiscal year 2001-02. The number operating at

an average capacity of 90-99 percent declined to nine.

22

The number of rated beds ranges

from 7 in Pickett County to 2,797 at the Shelby County Criminal Justice Center. (See

Appendix C.)

• In fiscal year 2002-03, local jails held an average of 2,301 DOC inmates awaiting transfer to

state prisons. According to the June 2003 Tennessee Jail Summary Report, DOC had 1,956

inmates awaiting transfer from jails to state facilities.

23

• The total number of state and local inmates in county jails has increased by almost 56 percent

since fiscal year 1992. Although DOC prisoners awaiting transfer to penitentiaries have

increased by about 13 percent since 1992, local felons have increased by almost 58 percent.

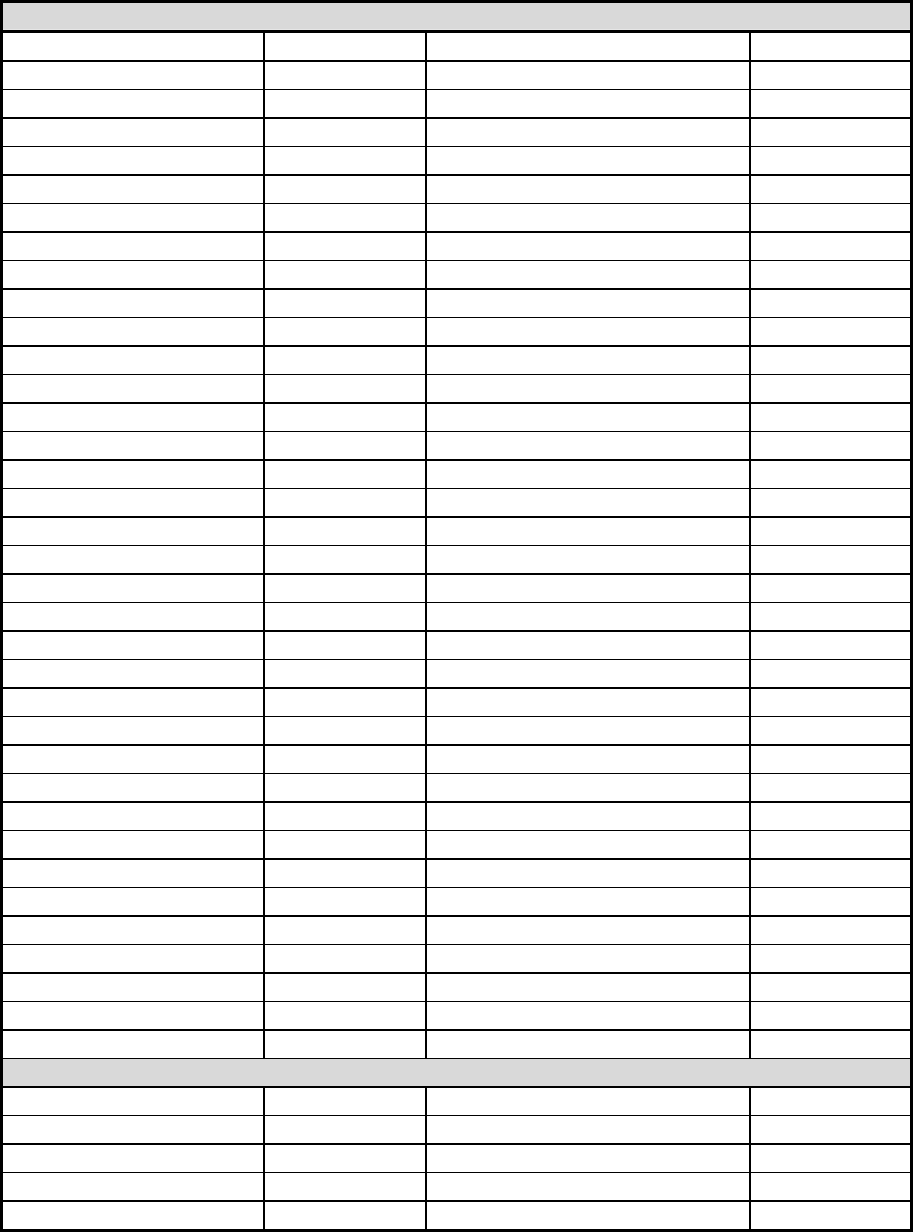

Exhibit 2 shows the increase in jail inmates from FY1991-92 through FY2002-03.

20

Wayne N. Welsh, Counties in Court, Temple University Press, 1995, p. 4.

21

Tennessee Department of Correction Monthly Jail Reports. Data in the TDOC monthly jail report is received from

each of the county jails. On the third Friday of every month, each of the county jails in Tennessee completes and

submits a monthly jail report form to the district Parole Officer. The officer then faxes each of the jail reports

without modification to the Tennessee Department of Correction (TDOC) and the information is recorded and

reproduced without modification.

22

TDOC Monthly Jail Report. TDOC maintains data on facilities in Johnson City and Kingsport but these were

excluded from analysis because they are municipal facilities and this project focused on county operated facilities

and facilities in which the county contracts with a private prison company.

23

Tennessee Department of Correction, Tennessee Jail Summary Report, June 2003, accessed July 15, 2003,

http://www.state.tn.us/correction/pdf/jail_jun03.pdf

.

8

• Even if the Department of Correction removed all its prisoners awaiting transfer, some

counties would be overcrowded. (See Exhibit 3.)

• According to a 2002 Office of Research survey of sheriffs, overcrowding is one condition

named in at least 19 percent of lawsuits brought against facilities and in six percent of

consent decrees or court orders. Of the 79 responding sheriffs, 48 (61 percent) believe that

overcrowding is one of the most important issues facing jails in the next five years. Federal

courts have ordered a number of counties, including Shelby, Madison, Knox, Hamilton, and

Davidson, to reduce the number of inmates.

o An attorney who sued Knox County in 1986 because of jail overcrowding announced

in October 2002 that he expects to ask the U.S. District Court to hold the county and

its sheriff in contempt of court because the jail repeatedly exceeded a mandated 215-

prisoner limit.

In 1997, a judge found the county in contempt for violating the cap and threatened to

fine the county until it found a solution. Attempts to build a new justice center have

collapsed.

24

o The Hamilton County jail could lose its certification because it failed to relieve

overcrowding. The average population in FY 2002 was approximately 578 with an

average capacity of 497.

25

TCI has repeatedly certified the facility because officials

promised to correct the problems. In 2001, TCI certified the facility based on a

planned expansion of the Silverdale Workhouse for federal prisoners, which is

expected to be completed in 2003.

26

A Hamilton County general sessions judge,

citing concerns regarding overcrowding and safety in the jail, began delaying the date

some non-violent offenders must report to the jail to serve their sentence and placing

these offenders in community corrections programs until the inmate population at the

jail decreases.

27

The Chattanooga police chief announced a new alternative

sentencing program called Project Transformation that offers drug offenders

counseling and job training classes rather than jail time.

28

o In Davidson County, federal court supervision ended in March 2002, 12 years after

the court imposed population limits on two of its facilities. However, in October

2002, the Davidson County General Sessions Court began conducting Saturday

sessions to move misdemeanants through the system more quickly because the

facility was becoming overcrowded again. The Saturday sessions handle offenders

who are arrested on the weekend, but must appear before a judge to have bail set.

Before the court began weekend sessions, defendants who might otherwise be out on

bail were held in the overcrowded jail.

29

24

Randy Kenner and Jamie Satterfield, “Full Jail Puts County on Spot,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, October 18, 2002.

25

Tennessee Department of Correction Monthly Jail Reports.

26

“Hamilton Jail Recertification May Be In Trouble Because of Overcrowding,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, October

23, 2002.

27

Telephone interview with Judge Bob Moon, Hamilton County General Sessions Judge, March 24, 2003.

28

“Hamilton Jail Tries Alternative Sentencing With Drug Offenders,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, October 25, 2002.

29

“Saturday Court is Helpful,” Tennessean, October 25, 2002.

9

Davidson County has also established a drug court that offers treatment as an

alternative to incarceration.

30

Davidson County has funded approximately $38 million

toward the renovation of and addition to the Criminal Justice Center and the

Correctional Work Center for an additional 1,000 beds.

31

• From 1996-2001, 24 counties increased jail capacity by building new jails, 19 counties

renovated existing facilities, and 14 added new space to existing facilities.

• According to the officials responding to the survey, 10 counties have immediate plans to

construct new jails, 14 counties plan to expand existing jails, and 11 will renovate existing

jail space. Over the years, some counties have added to their capacities by converting non-

traditional space, such as chapels, recreation areas, a library, and hallways, into dorms.

Exhibit 2 includes the statewide Tennessee jail population by inmate category from FY 91-92 to

FY 01-02. Analysis of this data can help identify past trends and anticipate future needs.

Exhibit 2: Jail Inmates from FY1991-92 through FY2002-03

Fiscal Year TDOC

Backups

Local

Felons

Other

Convicted

Felons

Others Convicted

Mis-

demeanants

Pre-trial

Felons

Pre-trial

Mis-

demeanants

Total

FY 91-92

2,041 2,638 1,222 285 3,098 3,000 814 13,098

FY 92-93

1,227 2,725 989 289 3,192 2,638 831 11,890

FY 93-94

1,156 2,920 1,073 273 3,371 2,756 904 12,451

FY 94-95

1,773 3,221 937 346 3,712 3,225 1,063 14,277

FY 95-96

2,042 3,350 1,082 330 3,956 3,452 1,287 15,499

FY 96-97

1,894 3,447 1,010 496 4,415 3,563 1,572 16,397

FY 97-98

1,617 3,515 1,070 632 4,613 3,972 1,739 17,160

FY 98-99

1,941 3,758 1,125 623 4,944 4,267 1,732 18,390

FY 99-00

1,927 3,917 1,136 797 4,821 4,538 1,802 18,935

FY 00-01

1,737 3,743 634 730 4,659 5,123 1,881 18,507

FY 01-02

2,143 4,137 555 811 4,982 5,333 2,158 20,118

FY 02-03

2,301 4,159 459 811 4,780 5,652 2,232 20,393

Change from

FY 91-92 to

FY 02-03

13% 58% -62% 185% 54% 88% 174% 56%

Source: Tennessee Department of Correction, Tennessee Jail Summary Report, June 2003, accessed July 15, 2003,

http://www.state.tn.us/correction/pdf/jail_jun03.pdf

.

A National Institute of Corrections publication states that jail crowding is a criminal justice

system (emphasis added) issue, and its roots lie with decisions made by officials outside the jail,

such as police, judges, prosecutors, and probation officers.

32

Like some other communities,

Shelby and Davidson Counties have created criminal justice coordination committees to examine

30

Telephone interview with David Byrne, Director of Court Annexed Programs, Davidson County Drug Court,

March 25, 2003.

31

Memorandum to Margaret Rose, Office of Research, from Karla Crocker, Communications Manager/Legislative

Liaison, Davidson County Sheriff’s Office, Feb. 6, 2003.

32

U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections (Mark Cuniff- National Association of Criminal

Justice Planners), Jail Crowding: Understanding Jail Population Dynamics, January 2002, p. 16.

http://www.nicic.org/pubs/2002/017209.pdf

. (accessed February 1, 2002).

10

jail crowding and other criminal justice issues. The committees provide a forum for key justice

system professionals (such as law enforcement officials, judges, prosecutors, and public

defenders) and other government officials to discuss justice system challenges. Committees

analyze the implications that individual agency decisions impose on the entire criminal justice

system. Office of Research staff interviewed representatives from the two Tennessee committees

and a similar group in Louisville. Members usually serve the same persons in the criminal justice

system, albeit in different capacities. Communities often form this type of committee in response

to a crisis rather than as a preventive measure.

Exhibit 3: Overcrowded Jails (Excludes DOC Backups)

Facility Percent Capacity

Excluding DOC

Backups

Facility Percent Capacity

Excluding DOC

Backups

Bedford

108%

Houston

113%

Bledsoe

189%

Humphreys

102%

Bradley

163%

Jackson

114%

Campbell

260%

Jefferson

118%

Carter

192%

Johnson

129%

Claiborne

182%

Lawrence

165%

Davidson CJC

104%

Loudon

204%

Davidson HD1

102%

Marshall

111%

Davidson CWC

103%

Monroe

109%

Davidson CCA

143%

Perry

106%

Fentress

115%

Pickett

133%

Gibson

114%

Polk

133%

Greene

153%

Roane

126%

Hamblen

110%

Scott

119%

Hamilton Jail

127%

Sequatchie

113%

Hardin

187%

Sumner

139%

Hawkins

102%

Warren

191%

Henderson

115%

Wayne

179%

Hickman

102%

Note: Only includes June 2003 data.

Source: Tennessee Department of Correction, Tennessee Jail Summary Report, June 2003, accessed July 15, 2003,

http://www.state.tn.us/correction/pdf/jail_jun03.pdf.

Tennessee’s continuing failure to provide adequate capacity in state prisons has

contributed to overcrowding in some local jails. Tennessee statutes address only state

prison overcrowding but offer no contingencies for overcrowded local jails. Inmate lawsuits

against Tennessee resulted in several pieces of legislation that allowed the state to respond to

prison overcrowding. These laws, combined with “The Reduction of Prison Overcrowding Act,”

specify that the governor can declare a state of overcrowding when the prison population exceeds

95 percent of capacity for 30 days or when there are reasonable grounds to believe that within 30

11

days capacity will be 95 percent. The statute allows the governor to direct the Commissioner of

Correction to notify all state judges and sheriffs to hold certain inmates until state facilities have

lowered their population to 90 percent of capacity.

33

The department has operated under this

statute continuously since the 1980s. The County Correctional Incentives Program (CCIP)

provides financial incentives for counties to hold felony offenders locally.

34

T.C.A. 41-4-140 (b)(2) and (e) specify that TCI cannot deny certification solely because of

overcrowding caused by DOC prisoners held in local jails. When determining compliance with

certain standards, TCI does not count DOC inmates awaiting transfer if the number is greater

than six percent of the county’s total average prisoner population over the preceding 90 days.

35

In Michigan, the County Jail Overcrowding State of Emergency Statute requires sheriffs to

notify judges, county executives, and other officials when the county jail population exceeds 100

percent of capacity for seven consecutive days. The Michigan statute outlines actions that

officials may take to reduce the population.

36

Tennessee statutes governing the transfer of state prisoners from county jails conflict with

each other. T.C.A. 41-8-106(g) requires the department to take into custody all convicted felons

within 14 days of receiving sentencing documents from the courts of counties not under contract

with the County Correctional Incentives Program. On the other hand, T.C.A. 41-1-504 (a)(2)

allows the department to delay transfer of felons who had been released on bail prior to

conviction for up to 60 days until the prison capacity drops to 90 percent. As a result, some

counties operate overcrowded facilities and often request other counties to hold some of their

inmates.

In the 1989 case, Dalton Roberts et. al v. Tennessee Department of Correction, et al., Hamilton,

Davidson, Knox, and Madison Counties sued the state for shifting its overcrowding burden to

their facilities. The Middle Tennessee District of the U.S. District Court placed certain limits on

the number of inmates that could be held in those facilities.

37

Because of the suit, the Department

of Correction gives priority to inmates in those facilities when deciding which inmates to transfer

to state facilities.

In late October 2002, the department began placing inmates in the Whiteville Correctional

Facility.

38

The Whiteville Correctional Facility in Hardeman County is owned by Corrections

Corporation of American (CCA).

33

T.C.A. 41-1-501 et.seq.

34

T.C.A. 41-8-101 et.seq.

35

Rules of the Tennessee Corrections Institute, Correctional Facilities Inspection, Chapter 1400-1 Minimum

Standards for Local Correctional Facilities, pp. 2-3 accessed July 27, 2001

http://www.state.tn.us/sos/rules/1400/1400-01.pdf

.

36

Michigan Compiled Laws § 801.55 and 801.56.

37

Dalton Roberts, et.al. v. Tennessee Department of Correction, et.al., United States District Court Middle

Tennessee District, Nashville Division, 1989, No. 3-89-0893.

38

Email to Brian Doss, Office of Research, from Howard Cook, Director of Classification and Acting Assistant

Commissioner of Operations, Tennessee Department of Correction, March 24, 2003.

12

Other recent additions to DOC capacity include:

• 1,536 new beds by construction at West Tennessee in 1998,

• 188 new beds by construction at DeBerry Special Needs Facility in 1998,

• 500 beds by expanding the Hardeman County contract in 1999,

• 256 beds by construction at the Tennessee Prison for Women in 2001, and

• 170 beds by double-celling at the Northeast Correctional Facility in 2002.

39

DOC and the Department of Finance and Administration have unsuccessfully attempted to locate

a suitable site for a new prison to increase capacity for a number of years. Plans being considered

are contingent on sites being conducive to construction and occupation. Administration officials

will report back to the Select Oversight Committee on Corrections when recommendations are

final.

In spite of T.C.A. 41-4-141, which allows two or more counties to jointly operate a jail, no

Tennessee counties have done so. As a result, some counties miss the opportunity to save

county funds and to lower their liability risks. A regional jail is defined as a correctional facility

in which two or more jurisdictions administer, operate, and finance the capital and operating

costs of the facility.

40

Authorities in other states use various approaches to operating regional jails; for example, in

some areas the agreement may specify that one jurisdiction may actually operate the facility, but

all participating jurisdictions equally share policy and decision-making responsibilities. In other

jurisdictions, adjoining counties may contract with a single county to house their prisoners and

relinquish their authority regarding policy and decision-making. Another option occurs when

each participating county operates its own facility for pre-trial inmates, but joins with other

jurisdictions for post-conviction incarcerations.

Sheriffs and county executives in some Tennessee counties have discussed the possibility of

creating regional jails, but could not reach agreement. Any attempt to establish a regional jail

calls for an examination of several issues. Some of these issues are:

• a perceived loss of authority by some county officials;

• a perception that not all counties are contributing equally;

• differing management styles;

• an increase in transportation costs;

• attorney complaints; and

• disagreements over the location of the facility.

39

Telephone conversation with Sendy Parker, Assistant to the Deputy Commissioner, Tennessee Department of

Correction, October 24, 2002.

40

National Institute of Corrections, Briefing Paper: Regional Jails, January 1992, p.1

http://www.nicic.org/pubs/1992/010049.pdf

(accessed February 4, 2002).

13

Jail Conditions, Standards, Inspections, and Training

Conditions

Comptroller’s staff observed unsafe and unsanitary conditions in some of the jails visited

during this study. Comptroller’s staff visited 11 jails during this study. Staff selected rural,

urban, and medium sized counties in all three grand divisions of the state. Additionally, staff

chose some counties recommended as model facilities and others described as substandard. Two

of the jails were new with no visible problems. Researchers observed the following conditions

that pose danger or violate TCI standards in some of the other facilities:

• overcrowding with inmates sleeping on the floor in cell areas or in hallways, blocking

exits;

• lack of clear markings for emergency exits;

• lack of male/female sight and sound separation;

• lack of sight and sound separation for juveniles;

• inability to separate inmates classified as violent from those determined to be non-

violent;

• excessive personal items;

• items that could be used for suicide or assaults, such as ropes for hanging towels, glass

mirror in maximum security cells, exposed television cords and cables, other electrical

cords;

• bare light bulb with exposed wiring hanging from ceiling;

• darkened cell blocks;

• no visual contact except during walk-throughs;

• lack of adequate exercise areas; and

• faulty plumbing.

Standards

The Tennessee Corrections Institute has no power to enforce its standards, resulting in

some jail conditions that endanger inmates, staff, and the public. In 2002,

25 county jails failed to meet certification standards. Without sanctions, counties often fail to

correct conditions that may be dangerous and likely to result in costly lawsuits. Fifty-three

sheriffs (67 percent of respondents) reported on the Comptroller’s survey that inmates have sued

their facilities within the last five calendar years. According to most sheriffs and jail

administrators interviewed, many suits are frivolous and eventually dismissed; however as of

calendar year 2001, nine sheriffs (11 percent) stated their jails are under a court order or consent

decree.

However, T.C.A. 41-7-101 et. seq., which created TCI, does not stipulate sanctions against

facilities not meeting standards. T.C.A. 41-4-140(a)(4) states that TCI has the power to establish

and enforce procedures to ensure compliance with its standards to guarantee the welfare of

persons in institutions. TCI personnel define that enforcement authority as the denial of

certification.

41

Non-certified facilities are likely less defensible in a lawsuit and could lose

insurance coverage.

41

Telephone conversation with Peggy Sawyer, Assistant Director, Tennessee Corrections Institute, Oct. 2, 2002.

14

Other Tennessee regulatory staff, including nursing home inspectors, food establishment

inspectors, and fire marshals, have authority to penalize non-compliant facilities with sanctions

such as fines, restricted admission, or closure.

Sanctions imposed in other states for non-certification vary. For example,

• Kentucky can close facilities.

• Louisiana places the facility on a 120-day notice and removes inmates if non-

compliance continues.

• Maryland requires jails to develop a compliance plan and reassesses the facility after

six months with continued follow-ups until the facility is in compliance; ultimately

the state can close facilities.

• Nebraska can terminate state reimbursements for inmates or close facilities.

• South Carolina employs a range of intermediate sanctions and can ultimately close

facilities.

• Virginia may place facilities on probation, decertify them, or close them.

42

In 2001 the General Assembly considered, but did not pass, a bill that would have given TCI

more enforcement authority. House Bill 398/Senate Bill 764 would have allowed TCI to:

• issue provisional certifications;

• decertify facilities;

• exclude counties from participating in the County Correctional Incentives Act of 1981;

and

• ask the Attorney General and Reporter to petition circuit courts to prohibit inmates from

being confined in facilities that do not meet standards or impose threats to the health or

safety of inmates.

TCI continues to certify inadequate and overcrowded jails that do not meet state

standards. T.C.A. 41-4-140(d) prohibits TCI from decertifying deficient facilities if the county

submits a plan within 60 days of the initial inspection to correct its “fixed ratio deficiencies.”

Fixed ratio deficiencies refer to square footage and/or showers and toilets as well as jail capacity.

TCI accepts plans that include:

• transferring inmates to the Department of Correction,

• asking judges to grant early release of some inmates,

• lowering bonds of some inmates,

• contracting with other counties to house inmates,

• renovating to add beds,

• adding to an existing facility, or

• building a new facility.

43

42

Judith T. Nestrud and Thomas A. Rosazza, Rosazza Associates, Inc., State Inspection and Standard Program

Survey, July, 1999, p. 19-21.

43

Memorandum from Peggy Sawyer, Assistant Director, TCI, to Brian Doss, Office of Research, October 3, 2002.

15

Many counties delay implementing their plans indefinitely, yet TCI continues to certify the

facilities. For example, the Department of Correction might be unable to accept enough inmates

to eliminate an overcrowding deficiency or judges might refuse to grant early releases or lower

bonds. Plans to build a new facility or expand housing units in an existing jail may be postponed

for years because of a lack of funding, yet TCI certifies the facility because county officials

submit evidence of discussing the issue.

The Knox County Grand Jury of the November-December 2002 term visited the Knox County

Jail and documented several areas of concern including no emergency lighting in the pods, an

easily accessible waste receptacle containing used needles in the medical area, and the need for

an upgraded ventilation system.

44

The county scrapped plans to build a new facility in 2000.

45

Regardless, TCI certified this facility in calendar year 2002.

TCI standards do not appear to meet the level of quality mandated by T.C.A. 41-4-140. This

section requires that: “Such standards shall be established by the Tennessee Corrections Institute

and shall approximate, insofar as possible, those standards established by the inspector of jails,

federal bureau of prisons, and the American Correctional Association's Manual of Correctional

Standards, or such other similar publications as the institute shall deem necessary.”

However, TCI standards are minimal and not as comprehensive as those of the American

Correctional Association. For example, ACA standards include items that TCI standards omit,

such as:

• a written policy, procedure, and practice for monthly inspections by a qualified fire and

safety officer for compliance with safety and fire prevention standards;

• programs to prepare inmates for release;

• population projection plans to anticipate future needs;

• formulas to determine the number of staff needed for essential positions; and

• qualifications for jail administrators.

As a result, Tennessee jails may be substandard in comparison to jails that comply with ACA

standards.

46

TCI has not developed minimum qualification standards for correctional officers and jail

administrators. Few local correctional officer positions are civil service. Newly elected sheriffs

usually hire new officers. TCI standards require that correctional officers receive 40 hours of

basic training within the first year of employment. According to several jail administrators and

44

Knox County Grand Jury, Report of the Knox County Grand Jury of Their Visits of Knox County Institutions and

Knox County-Operated Facilities During the November –December 2002 Term, p. 1.

45

Randy Kenner, “Report: County Jail Has Health, Security Woes,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, October 31, 2002.

46

To be ACA accredited, a facility must comply with 100 percent of all applicable mandatory standards and at least

90 percent of all non-mandatory standards. The ACA Adult Local Detention Facilities manual has 440 standards (41

mandatory and 399 non-mandatory standards.) For those non-mandatory standards not in compliance, there must be

a plan of action to bring them into compliance within a reasonable time or a request for the noncompliance to be

waived.

16

sheriffs, newly hired correctional officers frequently report on their first day with no experience

or training on how to perform their duties or handle unruly inmates and emergencies.

Inspections

The Tennessee Corrections Institute appears to have inadequate staff to fulfill its mandate.

TCI gradually reduced its staff from 26 positions in 1982 to 11 in 2002 because of forced budget

cuts.

47

The agency’s staff now consists of only six inspectors, an executive director, and clerical

staff. The lack of staff results in the following conditions that affect the quality of jail

inspections:

• The six inspectors provide training and technical assistance to jail staff as well as

conducting inspections. Mixing regulatory and assistance functions can result in a lack of

objectivity by inspectors.

• Inspectors may have inadequate time to perform quality inspections within statutory time

limits. The six inspectors must cover 14 city jails, 95 county jails, nine jail annexes, and

eight correctional work facilities within each calendar year. If a facility fails its initial

inspection, inspectors must revisit the facility within 60 days to assess whether the jail

has corrected violations.

48

To comply with the law, inspectors must complete all initial

inspections by November 1. In addition to conducting inspections, TCI staff train

correctional officers, testify in court, provide technical assistance to jail administrators,

and approve plans for new facility construction or renovation.

• Having so few positions prevents TCI from employing staff with specialized

qualifications. The inspectors cannot be expected to have expert knowledge in all aspects

of jail management and facility design, such as reading blueprints, wiring, and plumbing.

• The low number of staff can also result in less than thorough inspections. TCI staff

evaluate facilities on 136 standards: physical plant; administration and management;

personnel; security; discipline; sanitation and maintenance; food services; mail and

visitation; medical services; inmate supervision; classification; hygiene; programs and

activities; and admissions, records, and release.

49

• Office of Research staff accompanied TCI inspectors on three inspections, each

completed in approximately four hours by a single inspector. Because of the numerous

standards, four hours may not be sufficient to complete a comprehensive inspection.

Under these conditions, staff may not be able to thoroughly examine compliance with

each standard.

• Lone TCI inspectors conduct most jail inspections. Working in teams can result in a

more thorough inspection and discovery of standards violations. A team of two may

inspect larger facilities. However, in such instances the inspectors examine different

47

Interview with Roy Nixon, former Executive Director, and Peggy Sawyer, Assistant Director, Tennessee

Corrections Institute, Sept. 19, 2002.

48

T.C.A. 41-4-140 (b)(1).

49

Rules of the Tennessee Corrections Institute, Correctional Facilities Inspection,

http://www.state.tn.us/sos/rules/1400/1400-01.pdf

(accessed July 27, 2001).

17

aspects of the facility. In other words, one inspector observes the physical plant while the

other inspector reviews records.

50

Inspectors in 13 other states inspect jails alone;

inspectors in 11 states inspect jails in teams; and in six states either one inspector or a

team inspects jails.

51

TCI inspection practices appear inadequate to ensure safe and secure jails. Office of

Research staff observed several problems with TCI’s inspection practices during jail inspections:

• Inspectors conduct their examinations and interpret agency standards in various ways.

TCI’s executive director allows the inspectors to interpret the standards as they

understand them as long as they can defend their decisions in court. Non-uniform

interpretation of standards may result in inconsistency across the state and the

certification of some facilities that may not fully meet standards. Office of Research staff

members accompanied inspectors to three jails and observed that the tone and

thoroughness of the inspections varied.

•

Although TCI inspections are unannounced, they generally occur within the same or an

adjacent month of the previous year’s inspection. As a result, jail staff can anticipate

inspections and present themselves in ways during the inspections that do not reflect their

normal routines and practices.

•

TCI generally assigns inspectors to the same jails every year. This practice can result in

close relationships with jail staff that may compromise the integrity of inspections and

certification. The TCI director explained that inspectors live across the state and

generally inspect facilities in the regions where they live, with the exception of their

home counties. This practice reduces travel time and expenditures.

• When researchers accompanied TCI staff on inspections, some inspectors exhibited a

lack of attention to detail. For example, on one inspection, TCI staff did not point out

numerous safety hazards, such as exposed wiring, nor did that inspector advise jail

personnel to remove dangerous objects. Both the inspector and the jail administrator

acknowledged that the facility was uncertifiable because of physical plant conditions. In

spite of this, both parties should take steps to ensure the safety of staff and inmates.

Staff in one jail indicated that the local fire and health departments and the county risk manager

also conduct annual inspections to ensure that the facility is safe regardless of TCI’s report. Fire

department staff examine inmate living areas, office space, and chemical storage to advise jail

staff of potential fire hazards. The health department inspects inmate living areas, heating and

ventilation units, food services, and pharmaceutical control. The county risk manager primarily

screens for interests such as equipment safety and electrical hazards.

52

50

Interview with Roy Nixon, former Executive Director, and Peggy Sawyer, Assistant Director, Tennessee

Corrections Institute, Sept. 19, 2002.

51

Judith T. Nestrud and Thomas A. Rosazza, State Inspection and Standard Program Survey, July 1999,

p. 18.

52

Telephone conversation with Jim Hart, Chief of Corrections, Hamilton County Sheriff’s Department, October 23,

2002.

18