Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

1

Final Project Report for Powering Small Business: Understanding the Impact of Solar

Energy Under Different Pricing Schemes

William Jack and Tavneet Suri

I. Introduction

This report details the progress on the project “Powering Small Business: Understanding the Impact of

Solar Energy Under Different Pricing Schemes” set up in Kenya in 2013.

587 million people (69.5% of the population) lack access to electricity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Retailers

with poor access to electricity have limited means to keep their shops open at night. This limits their

ability to operate during evening hours and reach customers who might be at work during the day.

Solutions like kerosene do a poor job of lighting the room and have negative health effects. Besides,

traditional off-grid solutions require significant one time investments, making them unrealistic for

poorer consumers.

This project studies the pricing schemes for a new solar technology that combines solar power, mobile

repayment, and mobile enforcement. We are partnering with Angaza Design who will roll out 1000 units

of their Solite-3 – a solar-powered device that provides light and charges phones. The devices allow

payment via mobile money and monitoring of payments with enforcement upon non-payment. This

enables Angaza to ask retailers for a very low and affordable down payment and allows them to

gradually pay back the full amount of the device over time, based on use and at no transaction cost

(PAYG using M-PESA, the current mobile money system in Kenya).

The project aims to study three broad sets of research questions:

(i) What is the impact of electricity (and light) on small retailers? Retailers may be able to keep

their shops open later, and could get additional income from phone charging. They may also

offset current kerosene or lamp expenditures.

(ii) What is the impact of mobile repayments and mobile enforcement on asset purchases relating

to take-up, default rates and use? This is a very cheap and simple way to enforce credit

contracts in environments where such enforcement is usually extremely costly and involves

door to door, group visits and in person collections.

(iii) What is the impact of varying the pricing structure? What is the effect of different per-hour

prices on take-up, default rates and energy consumption? The variation in the price structure

also helps us determine how to optimally price such an asset in a developing country

environment.

The study is being conducted in low-income peri-urban areas of Nairobi, Kenya.

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

2

II. Experimental Design and Research Questions

Angaza Design has agreed to offer 1000 Solite-3s as part of the research study. We have selected about

1800 retailers that satisfy Angaza’s criteria as potential clients. They will be randomly assigned to five

treatment groups and one control group: each group having 300 retailers. Retailers in the five

treatment groups are offered the Solite-3 under varying conditions which allows us to understand the

impact of different pricing structures and technologies.

Pricing options

There are three prices at which hours of power can be purchased:

Basic service price: Kshs 15

Valued user price: Kshs 10

Default price: Kshs 20

Option 1: Basic service plan (Pay As You Go)

Customer can purchase power in any increments at a per-hour price of Kshs 15. There is no weekly

minimum purchase required. Payments continue until the simple undiscounted sum reaches the capital

cost of the product: Kshs 8,000.

Option 2: Valued user plan with enforcement

Customer can purchase power in any increments at a per-hour price of Kshs 10 , but over the course of

any calendar week, starting on the day of the week on which the unit first enters service, at least Kshs

150 much be deposited.

If in a given calendar week the customer deposits less than Kshs 150, then the customer enters a default

period. Starting on the first day of the following week, the per-hour price switches to the penalty or

default rate of Kshs 20. The customer faces this per-hour price until Kshs 150 have been deposited

within a week. At that point, the customer reverts to paying a per-hour price of Kshs 10 for the rest of

the week. At the beginning of the next week, the customer is deemed to be “in good standing” and faces

a per-hour price of Kshs 10, and must deposit Kshs 150 again. However, if during the default period the

customer does not deposit Kshs 150 within the first week, the per-hour price remains at the default

rate, Kshs20, into the next week. This continues until during the course of one calendar week the

customer has been able to pay a total of Kshs 150.

Option 3: Valued user plan without enforcement

This is the same as Option 2, but the requirement to deposit Kshs 150 each week is not enforced. That

is, if less than Kshs 150 is deposited in a given week, no change occurs in the following week. Option 3 is

similar to Option 1 but with simply a lower per-hour price.

Treatment arms

With these three pricing options, we defined the following treatment groups

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

3

Treatment A: Pricing option 1 offered

Treatment B: Pricing option 2 offered

Treatment C: Pricing option 3 offered

Treatment D: Pricing option 2 offered, but converted to option 3 ex post.

Treatment E: Pricing option 1 offered, but converted to option 3 ex post.

This allows us to study 3 main questions:

(1) What is the impact of electricity?

To understand the impact of electricity on small retailers, we are administrating two baseline surveys,

three follow-up surveys and one endline survey and comparing relevant outcomes between retailers

offered the possibility to purchase a SOlite-3 in the treatment group with the highest take up –likely to

be treatment group C. These surveys collect data on business outcomes such as profits, revenue,

operating costs and operating hours. Through this randomized design, we will quantify the impacts of

providing light and energy to small retailers. We expect these benefits to include higher profits due to

stores being open longer and phone charging services being provided to customers.

(2) What is the impact of mobile repayments and mobile enforcement?

The Solite-3 automatically collects usage data in real time and Angaza’s internal systems collect

repayment data. Angaza Design has agreed to provide us with full access to this information. By

comparing adoption rates, repayment rates, usage and other outcomes between treatment groups B

and D, we can quantify the treatment effect of enforcement. Retailers in both treatment groups B and D

have been offered a low per hour price at the condition of being financially punished if they do not use

the Solite for more than Kshs 150 per week. Although retailers in treatment group D have decided to

purchase the product at these same conditions, the punishment is not enforced ex post. By comparing

both of these groups, we can determine the differences in behaviors when enforcement is cut

(Treatment group D). Similarly, the comparison between treatment groups C and D highlights the

selection effect of enforcement. Indeed, retailers in both groups do not get financially punished even if

the weekly Kshs 150 threshold is not reached. Average outcome differences might however exist as

retailers in both groups might have different characteristics having initially chosen to purchase the

product under different pricing schemes (each group’s self-selection was under different pricing terms).

(3) What is the impact of varying the price structure?

Groups are offered different per hour energy prices (Kshs 10 or Kshs 15) and comparing usage,

repayment rates and business outcomes between these groups will help us understand the importance

of pricing and price discrimination for small retailers. What impact on take up does an increase on per

hour price have? Does a lower per hour price encourage clients to consume more electricity and repay

more quickly or does it select unworthy clients who default? As part of this process, we will work closely

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

4

with Angaza Design to develop an optimal pricing structure that will maximize both adoption and

repayment rates.

Similarly to above, the comparison between Treatment group A (Kshs 15) and E (Kshs 10) allows us to

quantify the treatment effect of prices variation on business outcomes but also on repayment rates and

electricity usage. Comparing Treatment C to E allows us to calculate the selection effect of pricing as

retailers in both groups enjoy a low per hour price although those in E had initially purchased the device

assuming a higher per hour price. Therefore this comparison highlights the difference in the types of

customers who self-select in different pricing schemes.

Summary of the Experimental Arms

Treatment

Group

Name of

Group

Price per

hour

N

Role of Enforcement

Role of per hour price

Treatment A

Basic service

plan

Kshs 15

300

Treatment

effect

Treatment B

Valued user

plan with

enforcement

Kshs 10–

default Kshs

20

300

Treatment

effect

Treatment C

Valued user

plan without

enforcement

Kshs 10

300

Selection

effect

Selection

effect

Treatment D

Valued user

plan with

enforcement

dropped ex

post

Kshs 10

300

Treatment

effect

Selection

effect

Treatment E

Rebate on

basic service

plan ex post

Kshs 10

(coming from

Kshs 15)

300

Treatment

effect

Selection

effect

Control

Group

No Solite

300

III. Changes

III.a Location

In late 2012, the project was moved from Tanzania to Kenya after the implementers (Angaza Design)

realized that the distribution of solar panels in Tanzania would be much costlier than expected. Their

main distributing partner in East Africa is Sunny Money whose presence in Tanzania is too limited for a

project this size. In addition, the high prevalence and use of mobile money in Kenya meant that the take

up of these solar lights would be much higher in Kenya since mobile money is used to pay off the asset.

The penetration of mobile money is much lower in Tanzania which would have imposed further costs as

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

5

retailers would also have to be trained to use mobile money. The research team conducted a scoping

visit to Tanzania and also supported this move to Kenya.

III.b. Timeline

Although the length of the project remains the same, the project’s timeline has been shifted by a few

months due to (a) the change in location (b) the Kenyan General Elections and (c) the delay in delivery of

the Solite3 units. Firstly, the launch of the project was delayed due the change of location. Secondly,

Kenya’s presidential elections on March 4

th

meant the project activities had to be slowed down and

minimized during the few weeks around these events. Thirdly, Angaza Design has experienced delays in

shipping the units to Kenya, which are necessary before the start of the Implementation phase. We are

therefore hoping to start implementing end of April 2013. However, this delay has had no material

impact on the IGC component of the funding. The IGC funding was used to cover a portion of the capital

costs of the panels; the listing exercise we conducted in Nairobi to identify the relevant sample of

participating retailers; the first two baseline surveys across all 1800 retailers in the sample, the second

of which was just completed at the end of March, as we detail below. We have additional funds to cover

the rest of the study.

III.c. Experimental Treatment Groups

Experimental Treatment Groups were modified and increased from 5 to 6 (including the control group).

This was motivated by (i) on the ground piloting by our partner distributor and feasibility assessments

and (ii) technical limitations of Angaza’s products and internal systems.

IV. Progress to Date

The team invested significantly in setting up and piloting the project. A number of exploratory trips and

procedures were conducted both in Tanzania and in Kenya, which led to a shift of location to the latter

and the selection of adequate peri-urban areas in Nairobi. Eight neighborhoods were selected based on

(i) electrification rate (ii) density of retailers and (iii) type/size of retailers. The eight areas are

Kawangware, Kangemi, Uthiru, Waithaka, Dagoretti, Kikuyu, Kinoo and Wanginge.

In January 2013, our Research Team on the ground conducted a detailed census of all small retailers in

these neighborhoods -around 9440 retailers were recorded. 2300 of those have no access to electricity

and are forced to either shut before dark or use kerosene or candles at great costs. These retailers

could benefit hugely from solar energy and therefore became our target sample.

The first Baseline study was rolled out in February 2013 and took about three weeks to complete. 76%

of the sample was successfully surveyed (summary statistics reported below). The second Baseline

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

6

34%

21%

9.3%

8.6%

8.2%

7.2%

5.8%

4.9%

Kawangware Kangemi

Uthiru Waithaka

Kinoo Kikuyu

Wanginge Dagoretti

Other

Listing January 2013

Distribution of listed retailers per area

survey started in mid-March 2013 – after a break due to the General Election - and has been completed.

The implementation/distribution of the solar lights is scheduled for the end of April.

The Research Team and Angaza Designed partnered with Sunny Money, a global distributor of solar

lights operational in East Africa to set up distribution and servicing of the devices. Sunny Money has

successfully tested the products to confirm they meet their standards as well as national guidelines.

They have also set up a dealer network in the relevant Nairobi neighborhoods to facilitate distribution.

Indeed, 34 dealers were selected and recruited. They will be trained intensively to sell the solar devices

to the retailers, to offer technical assistance during set up and after-sale advices. Sunny Money is

responsible for this training. The dealers will only sell a device to retailers in exchange of a voucher that

will be distributed during a marketing round carried out by the Research Team. The purpose of these

vouchers is to make sure (1) retailers in the control group do not purchase these solar lights (no

transfers from the treatment groups to the control group) and (2) the retailers receive the correct

treatment, depending on which treatment group they belong to. All training and marketing material and

logistics have been organized for a rapid launch as soon as the products arrive in Nairobi.

Next, we report on some of the findings from the census we conducted as well as the first baseline. The

second baseline is currently being cleaned.

V. Summary Statistics:

V.a Listing

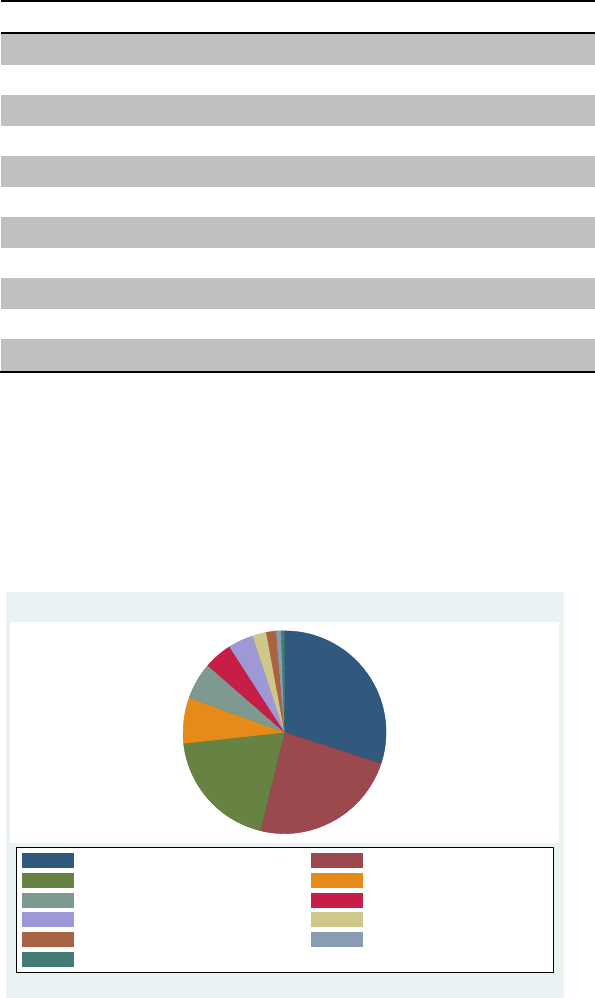

In January 2013 we conducted a listing of all small retailers in the eight areas of study. The research

team listed 9,437 small retailers. The table and graph below show the distribution of the 9,437 retailers

in the eight areas visited.

Graph 1:

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

7

Table 1: Distribution of listed retailers per area

Area

Freq.

%

Kawangware

3,203

33.94

Kangemi

1,983

21.01

Uthiru

873

9.25

Waithaka

811

8.59

Dagoretti

463

4.91

Kikuyu

678

7.18

Kinoo

772

8.18

Wanginge

543

5.75

Other

111

1.18

Total

9,437

100

The listing included all small retailers, irrespective of the type of shop they own. 30% of the listed

retailers who allowed us to report their type of shops own small kiosks and specialize in one item, such

as green grocers (Graph 2).

Graph 2:

Access to electricity:

Access to electricity also varies across these retailers. Although grid electricity seems to be available for

more than 88% of the retailers listed, only 49% report using grid electricity (see graphs 3 and 4).

30%

24%

19%

7.4%

5.8%

4.5%

4%

Food Specialized Duka Multi Product Duka/Kiosk

Clothes/Shoes/Accesoories Shop Non-Food Specialized Duka

Milk Bar/Eatery Other

Electronics or Music/CD Shop Beauty Shop/Cosmetics

Chemist or Traditional Medicine Wines and Spirit Shop/Bar

Stationary/Book Shop

Listing January 2013. 920 retailers did not report the type of shop and are not included in this graph

Distribution of listed retailers per type of shops

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

8

88%

2.1%

10%

Yes No

Missing Data

Listing January 2013

Potential access to grid electricity

Graph 3: Graph 4:

When retailers do have access and use grid electricity, they seem to rely primarily on it. Indeed, most of

the 49% who report using grid electricity list electricity as their first source of energy (48% of listed

retailers).

Table 2: Prime source of energy for listed retailers

Sources of energy for shop

Freq.

%

Electricity

4,550

48.21

Coal

18

0.19

Kerosene

1,083

11.48

Other oil

8

0.08

Gas (cooking gas, etc)

8

0.08

Solar

63

0.67

Wood

3

0.03

Candles

213

2.26

Batteries

119

1.26

Other

1,985

21.03

Missing

1,387

14.7

Total

9,437

100

Out of the 9,437 retailers listed, we selected 2,359 (25% of the listing) who had agreed to be included in

the listing and who did not use electricity as their first source of energy. This selection was based on the

assumption that a solar powered light and phone charger would be most beneficial to retailers with

limited access to electricity. The 2,359 retailers now constitute our sample.

49%

38%

12%

Yes No

Missing Data

Listing January 2013

Use of grid electricity

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

9

33%

25%

9.5%

8.4%

7.2%

6.2%

4.8%

4.6%

Kawangware Kangemi

Uthiru Kikuyu

Wanginge Dagoretti

Waithaka Kinoo

Other

Sample from Listing January 2013

Distribution of retailers in sample per area

V.II: Baseline 1 statistics

Baseline 1 was conducted in February 2013 and 1,783 surveys were completed

1

(76% of the sample).

The sample selected remains representative of the listing. As an example, more than 30% of our sample

is located in Kawangware and more than 20% in Kangemi, which matches the listing’s distribution of

locations (Graph 5). Similarly to the listing, food specialized kiosks form more than 30% of our sample

(Graph 6).

Graph 5:

Graph 6:

1

The remaining 14% were not surveyed due to refusals or retailers not available/found at the time of survey.

36%

27%

10%

9.7%

7.4%

6.1%

Food Specialized Duka Clothes/Shoes/Accessories

Multi Product Duka/Kiosk Non-Food Specialized Duka

Milk Bar/Eatery Other

Electronics or Music/CD Shop Beauty Shop/Cosmetics

Stationary/Book Shops Chemist or Traditional Medicine

Wines and Spirit Shop/Bar

Sample from Listing January 2013.

Distribution of retailers in sample per type of shops

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

10

Revenues/Profit:

From our Baseline 1 data, the sampled retailers make approximately 600 Kenyan shillings (US $7) of

profit daily and Kshs 1700 (US $20) of revenue daily (Table 3). The down-payment for the Solite-3 (Kshs

500) is therefore equivalent to about one day of profit.

Table 3: Daily Profit and Revenue for Retailers in Sample:

Daily Profit

Normal Day

Daily Profit

Good Day

Daily Profit

Bad Day

Daily Revenue

Normal Day

Daily Revenue

Good Day

Daily Revenue

Bad Day

N

1632

1638

1629

1681

1692

1682

Mean

586.6

1165.4

302.8

2307.2

3994.6

1310.5

Min

0

0

0

0

0

0

Max

5000

10000

3000

20000

30000

10000

p25

200

400

100

800

1000

400

p50

400

600

200

1500

2300

800

p75

700

1400

400

3000

5000

1500

Table 4: Monthly Profit and Revenue for Retailer in Sample:

One of our main research questions is the impact of the solar energy on the profits of the retailers. This

could happen via two mechanisms. First, shops can open for longer hours due to the additional light and

second, retailers could set up a phone charging business, adding a new revenue stream.

Hours of business:

Our baseline data shows that an average retailer opens his/her shop 10 hours a day and 6 days a week

(Table 5). He/she opens before 6 am three days a month and closes after 6pm 22 days. Interestingly,

Average

Monthly

Profit

Profit

Last

Month

Profit

2 Months

Ago

Profit

3 Months

ago

Average

Monthly

Revenue

Revenue

Last

Month

Revenue

2 Months

Ago

Revenue

3 Months

Ago

N

1558

1462

1410

1537

1446

1391

Mean

12807.1

11166.0

15071.6

12183.8

47976.0

43084.9

54488.2

46355.0

Min

0

0

0

0

0

0

Max

95000

120000

90000

384000

462000

400000

p25

4000

5000

4000

12000

14000

12000

p50

7500

10000

8000

25000

30000

27000

p75

15000

20000

15000

54000

70000

60000

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

11

73% of retailers would open for longer hours if electricity was cheaper or more reliable. If they could

open for longer, 41% would want to open earlier and 69% would open later (Graphs 7 to 10).

Table 5: Business Hours and Days for shops in sample

Number of hours

open per day

Number of days

open per week

Number of days open

before 6 am per month

Number of days open

after 6pm per month

N

1776

1778

1777

1773

Mean

10.9

6.4

3.7

22.1

p25

9

6

0

20

p50

11

6

0

27

p75

12

7

0

31

Graphs 7: Graph 8:

Graph 9: Graph 10:

71%

23%

2.6%

Yes No

Would not open longer Missing

Would retailers open their store later if they were to open longer

75%

24%

.62%

Yes No

Missing

Would retailers open their store longer hours if access to electricity was more reliable

42%

53%

2.6%

Yes No

Would not open longer Missing

Would retailers open their store earlier if they were to open longer

75%

25%

.62%

Yes No

Missing

Would retailers open their store longer hours if access to electricity was cheaper

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

12

As highlighted previously, profits could also be increased if the Solite-3 is used to set up a phone

charging business. Currently less than 2% of the retailers own such a business but an additional 68%

would consider offering this service if they had access to the Solite-3 as the demand seems to exist

(Graph 11).

Graph 11:

Sources of energy:

Finally, this project might create a shift from traditional energy sources to solar power. Coal and

Kerosene (in that order) seem to be popular energy sources for these retailers. Currently, an average

retailer spends for all energy purposes Kshs 145 ($ 1.70) on Kerosene per month and Kshs 300 ($3.50) on

Coal. If we restrict the analysis to those who do use Kerosene, an average user will spend Kshs 465

($5.50) per month on Kerosene and Kshs 3000 ($35) on Coal (Tables 6 and 7)

Table 6: Monthly Spending on Energy (dropping the top percentile)

Monthly Spending on Energy (dropping the top percentile)

Monthly

Expenditures

on Batteries

Monthly

Expenditures

on Candles

Monthly

Expenditures

on Coal

Monthly

Expenditures

on Electricity

Monthly

Expenditures

on Gas

Monthly

Expenditures

on Kerosene

N

1737

1737

1741

1725

0

1731

Mean

22.8

20.9

296.9

9.7

144.0

Min

0

0

0

0

0

Max

540

600

8400

563

1800

68%

29%

Already offers service Yes

No Missing

Baseline 1 February 2013

Existence of demand for mobile phone charging

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

13

p25

0

0

0

0

0

p50

0

0

0

0

0

p75

0

0

0

0

200

p90

40

0

6

0

600

p95

200

200

2400

0

750

Table 7: Monthly Spending on Energy for those using the source (dropping the top percentile)

Monthly Spending on Energy for those using the source (dropping the top percentile)

Monthly

Expenditures

on batteries

Monthly

Expenditures

on Candles

Monthly

Expenditures

on Coal

Monthly

Expenditures

on Electricity

Monthly

Expenditures

on Gas

Monthly

Expenditures

on Kerosene

N

178

169

175

59

0

540

Mean

222.1

214.9

2953.6

283.4

464.5

Min

8

6

6

40

1

Max

540

600

8400

563

1800

p25

120

50

960

120

240

p50

200

240

2400

300

335

p75

300

300

4650

400

600

p90

450

500

6200

500

900

p95

480

600

7200

520

1200

For lighting purposes, most retailers use kerosene – in our sample, 460 retailers use kerosene compared

to 130 who use candles, the second most used lighting input. Kerosene is not only the most used source

of energy for lighting, an average retailer also invests in Kerosene the most. Kshs 116 ($1.50) is spent on

Kerosene every month to provide light to their retail shop whereas Kshs 14 ($0.15) is invested in candles

monthly (Table 8). Similarly to the analysis for expenditures in energy, if we only focus on the retailers

who do use that input, expenditures in kerosene amounts to Kshs 440 ($5) per month for an average

user whereas only Kshs 180($2.10) are invested in candles. Interestingly, coal seems very expensive for

lighting (Table 9).

Table 8: Monthly Spending on Lighting (dropping the top percentile)

Monthly Spending on Lighting (dropping the top percentile)

Monthly

Expenditures on

Batteries

Monthly

Expenditures on

Candles

Monthly

Expenditures

on Coal

Monthly

Expenditures

on Gas

Monthly

Expenditures on

Kerosene

N

1733

1728

1745

0

1733

Mean

9.8

13.8

7.5

116.6

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

14

18%

81%

.62%

Yes No

Missing

Baseline 1 February 2013

% of retailers in sample who have purchased solar products

Min

0

0

0

0

Max

480

560

1440

1600

p25

0

0

0

0

p50

0

0

0

0

p75

0

0

0

60

p90

0

0

0

500

p95

0

80

0

620

Table 9: Monthly Spending on Lighting for those using the source (dropping the top percentile):

Monthly Spending on Lighting for those using the source (dropping the top percentile)

Monthly

Expenditures on

Batteries

Monthly

Expenditures on

Candles

Monthly

Expenditures

on Coal

Monthly

Expenditures

on Gas

Monthly

Expenditures on

Kerosene

N

80

131

22

0

458

Mean

212.9

181.4

598.5

441.2

Min

3

3

9

3

Max

480

560

1440

1600

p25

140

40

200

220

p50

200

150

455

310

p75

280

300

1050

600

p90

400

310

1300

900

p95

450

500

1400

1040

Finally, 81 % of our retailers in our sample have never used solar products (Graph 12), although half of

them have considered them (Graph 13). The main reasons for not purchasing solar products seem to be

primarily because they are too expensive (34% of the responses) (Graph 14).

Graph 12: Graph13:

49%

51%

Yes No

Baseline 1 February 2013. N=1444 (never used solar products)

% retailers in sample considering purchasing solar products having never used one

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

15

Graph 14:

VI. Timelines and Future Project Output

VI.a. Timeline

As described in Section IV, by the end of March 2013, we have conducted multiple exploratory trips, a

full census and two Baseline studies – the second Baseline data is currently being cleaned. The

implementation is to begin end of April and will run for about a month, depending on take-up and the

need for additional marketing rounds. Three follow-up surveys and one endline survey will then be

carried out from July to November 2013. As mentioned, we will intensively follow just one treatment

group and the control group.

The project is heavily co-funded by other sources and co- funding will cover for the remaining steps. We

expect to have results by the end of 2013.

VI.b Project output

Analysis will be based on two sources of data: (1) data collected by the Research Team during baseline

and follow–up surveys and (2) electronic data collected by Angaza including purchasing date, energy

usage, frequency of top-ups, amount spent, repayment and default rates, etc. Angaza’s electronic

system also collects usage data separately for the mobile phone charging and for the light.

Using the data collected, we expect to answer the three research questions outlined above. Firstly, we

will measure the impact of solar energy on businesses’ profits, revenues, working hours and energy

consumption. Secondly, we will determine whether enforcement is necessary for repayment in these

environments and whether it affects usage, repayment and default rates. Thirdly, we will analyze the

33%

24%

3.7%

9.8%

.96%

25%

3.4%

Too expensive No need as enough energy

Did not know of existence Skeptical

Location not exposed to sun Other

Missing

Baseline 1 February 2013. N=727 (never used & never considered using solar products)

Retailers' reasons for not purchasing solar products

Powering Small Businesses Final Report March 2013

16

pricing structure and quantify the importance of non-linear pricing on energy consumption and default

rates. We hope that this will contribute to emphasizing the importance of solar energy in East Africa and

how this can benefit poor retailers who may be unable to make the large investment costs needed for

solar panels. We also hope to show the importance of asset based loan financing and how mobile

money repayment and enforcement can reduce upfront costs and increase take-up. Finally, the data

collected will help Angaza and other companies select the best pricing scheme (the data in Baseline 1

was already used to determine adequate pricing of per hour energy).

VII. Conclusion

This project studies the take up, pricing and impact of solar panels in a developing country context.

These are important questions for an environment such as that faced by poor small scale retailers in

Kenya where liquidity constraints prevent them from making productive investments. Given our

baseline data on these retailers, it is clear that solar power could have immense gains, either by allowing

them to keep their stores open later or by reducing their expenses on kerosene and batteries, the costs

of which are reasonably high. This project aims to first look at the impacts of these solar panels. Second,

we test various pricing mechanisms of the asset to understand what best trades off take up and default

on the asset.

The IGC funding was crucial in the setup of the project. As mentioned above it was used to scope out

locations for the project, cover some capital costs of the panels, and to conduct a census and two

baseline surveys. We have additional funding to cover the parts of implementation we are responsible

for as well as the follow-up surveys.