1

Equality, diversity and inclusion in

recruitment to Public Health specialty

training in the United Kingdom

A report commissioned by the UK Recruitment Executive Group of Health

Education England and the Faculty of Public Health

Fran Bury MFPH

Richard Pinder FFPH FRCP

School of Public Health

Imperial College London

Final version

Date of Publication: November 2022

2

CONTENTS

Executive Summary 3

Introduction 5

Recruitment into Public Health Specialty Training 9

Methods 14

Findings 15

Options for action 27

Recommendations for the Recruitment Executive Group 31

Conclusion 32

References 33

Appendices 35

Appendix A. Detailed results from Analysis 1: Success rates 35

Appendix B. Detailed results from Analysis 2: Staged progression pipeline 38

Appendix C. Detailed results from Analysis 3: Assessment Centre performance 43

Cite as: Bury F, Pinder RJ. Equality, diversity and inclusion in recruitment to Public Health

specialty training in the United Kingdom. 2022. Imperial College London, London, United

Kingdom.

3

Executive Summary

Public Health is a profession that seeks a more equal and more equitable world. The Public Health

specialty training scheme is the primary route to becoming a senior Public Health professional in

the United Kingdom. Over recent years recruitment into Public Health specialty training has

become increasingly competitive. The recruitment process in 2022 received more than 1000

applications for approximately 70 places.

Established in 2009, the current multi-stage recruitment process involves eligibility checking,

psychometric assessment and interview. Previous academic analysis has shown the process to

be effective in selecting candidates likely to perform well in training.

While care has been taken to design and maintain a recruitment process that attempts to be

impartial, Health Education England’s Public Health Recruitment Executive Group has been

increasingly concerned about the risk of differential attainment – a phenomenon observed in many

clinical specialties and at many different levels, where some groups appear systematically

disadvantaged in their ability to progress.

After identifying trends suggesting differential attainment from routine monitoring, the Recruitment

Executive Group invited Imperial College London to independently analyse four years of

application data to determine the extent to which differential attainment may be present and, if

present, how it may be mitigated.

The applicant pool for Public Health is highly diverse. There was no evidence to suggest that

interviewers were unfairly discriminating against minoritised groups. There was no evidence that

first language or socioeconomic status was associated with success. The main point-of-loss for

some candidate groups appears to be within the psychometric testing stage. Candidates from

ethnic minority backgrounds, those who are older, those from international medical graduate

backgrounds and backgrounds other than medicine are materially under-represented by the end

of the process. After statistical adjustment these patterns remain, leading to the conclusion that

differential attainment is present in the process.

This report presents a range of options for the Recruitment Executive Group in mitigating future

differential attainment to enable Public Health to deliver on its mission to create a fairer world.

4

Abbreviations

About the authors

Fran Bury (FB) is a Public Health registrar training in London, and a member of the Faculty of

Public Health’s Equality and Diversity Special Interest Group. Prior to entering Public Health

specialty training she worked in the private sector and local government and then ran the

operations for a children’s charity in North London.

Richard Pinder (RJP) is a consultant and clinical academic in Public Health Medicine based in

the School of Public Health at Imperial College London. RJP was the technical co-lead for

Assessment Centre from 2017 to 2021 and a member of the Recruitment Executive Group during

that time.

AC

Assessment Centre

BOTM

Background other than medicine

FPH

Faculty of Public Health

HEE

Health Education England

IMG

International Medical Graduate

RANRA

Rust Advanced Numerical Reasoning Assessment - one of the three

psychometric tests used as the Assessment Centre

REG

Recruitment Executive Group

SC

Selection Centre

SJT

Situational Judgement Test - one of the three psychometric tests used

as the Assessment Centre

WG

Watson Glaser test of critical thinking - one of the three psychometric

tests used as the Assessment Centre

5

Introduction

Background

Public Health is a medical specialty rooted in identifying and dismantling structural barriers and

the inequity they drive. In this way, Public Health as a profession has been outwardly progressive

in advocating for greater equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) over decades. Over recent years

racism and injustice have been increasingly in the spotlight: a subject of widespread societal

concern and criticism.

Institutions (including the medical and public policy professions as a whole) are being challenged

more than ever before to demonstrate how equal, diverse and inclusive they really are. A measure

of this is the extent to which their workforce truly reflects the populations they serve.

In 2020, The BMJ published a news item reporting widespread ethnic disparities among

applicants deemed appointable for specialty training. Three-quarters of White colleagues were

deemed to be appointable in 2018 across specialties, compared to 53% of those from ethnic

minority backgrounds (Iacobucci, 2020). In this article, it was suggested Public Health recruitment

resulted in the lowest proportion of ethnic minority applicants being deemed appointable: 15%

compared to over 50% among the larger specialty training programmes.

The same report also suggested that Public Health exhibited the greatest ethnicity gap: with 36%

of White candidates deemed appointable, meaning White applicants were 2.4x more likely to be

deemed appointable than ethnic minority candidates. It has not been possible to determine the

raw data source for this analysis. And while drawing precise conclusions from these findings is

fraught with complexity, the analysis poses a valid question: is there differential attainment in

Public Health specialty recruitment?

Context

Governance and accountability

The UK Public Health Recruitment Executive Group (REG) is a committee of Health Education

England that reports to the Medical and Dental Recruitment and Selection (MDRS) Board. The

REG is responsible for overseeing the recruitment process for Public Health across the four

nations of the United Kingdom. The REG is led by two Consultant-level Co-Chairs: a regional

Head of School and a Training Programme Director. Its membership includes representatives of

Health Education East Midlands (the lead organisation for Public Health recruitment across the

four nations), the UK Faculty of Public Health, Consultant leads for the components of the

recruitment process and specialty registrar representatives.

6

Recruitment cycle and monitoring

For those outside the specialty, it is important to note that Public Health specialty training differs

from most other medical specialties. The Consultant workforce in Public Health comprises a

mixture of staff from medical backgrounds as well as backgrounds other than medicine (BOTM).

Today, this is mirrored in the eligibility for training as Public Health specialty training attracts

applicants from medical as well as BOTM backgrounds, with differing eligibility criteria applied.

As such, any recruitment process cannot assume a clinical background or indeed assess on the

basis of presumed clinical competence as is the case in most other specialities (including those

who rely on the Multi-Specialty Recruitment Assessment, MSRA).

The Public Health specialty recruitment cycle for candidates begins in November of each year,

with a three-stage recruitment process culminating the following March, when offers are made for

prospective registrars to start their training five months later in August. For the REG, the

recruitment cycle is an all-year programme with substantial planning and logistics work beginning

almost as soon as the preceding cycle has completed. For the purposes of this report, recruitment

cycles are referred to by their August intake year, meaning that the cycle that began in 2019

leading to appointments made for 2020, is referred to as the 2020 cycle.

A more detailed description of the recruitment process is included later in this report. However,

the quality assurance of the recruitment cycle has been reported every year in a late Spring-time

wash-up meeting since the current multi-stage process was introduced in 2009. Demographic

and equalities monitoring has been subject to scrutiny throughout that period. The current

recruitment design was successfully validated against postgraduate progression in terms of

annual appraisal and postgraduate examinations (Pashayan et al., 2016). However no similar

process beyond routine monitoring had been devised in relation to differential attainment. This

routine monitoring has demonstrated an association of non-White ethnicity and older age with

lower overall performance although single-year cohorts have until now precluded more robust

analyses. While a number of explanatory hypotheses have been proposed, there was insufficient

analytical capacity to test these properly. Efforts have been made over the period to prevent

differential attainment: unconscious bias training and a number of other safeguards have been

implemented following concerns that the interview panels might be unduly favouring certain

applicants.

Differential attainment

The UK General Medical Council defines differential attainment as the gap between attainment

levels of different groups of doctors, which exists in multiple contexts including recruitment,

examination, progression (General Medical Council, 2022). The GMC defines differential

attainment to be inherently unfair.

Commonly, the term discrimination, implies a process that is unfair. However, in one sense

discrimination is a technical process of differentiating one group from another and ultimately the

7

goal of all selection processes. While it is clear that discrimination relating to a protected

characteristic (within the Equality Act 2010, and associated Public Sector Equality Duty) is

absolutely unacceptable, the extent to which some elements of professional values and behaviour

are culturally underpinned can present challenges when trying to determine what outputs of a

selection process are intended (versus unintended), and acceptable (versus unacceptable).

For example, professional attitudes differ around the world in relation to punctuality. Therefore, it

is possible to debate the fairness of evaluating an applicant’s attitude towards punctuality through

a situational judgment test.

a

Likewise, in a professional environment where communication

capability is important, the extent to which English language proficiency (or lack thereof) is

intentionally or acceptably assessed can be questioned.

Differential attainment in medical training has been observed across many clinical specialties,

although research has traditionally focused on postgraduate examinations and progression

(McManus & Wakeford, 2014; Patterson et al., 2018; Tiffin & Paton, 2021). Much of the evidence

in medicine has focused on three groups: white UK medical graduates, non-White UK medical

graduates and international medical graduates (IMG) with clear trends showing poorer

progression statistics for the latter two groups when compared to the former.

Yet evidence is increasingly showing that differential attainment in respect of ethnicity occurs

early, even during undergraduate training (Gupta et al., 2021). While beliefs persist that such

disadvantage is attributable to biased examiners and selectors (Woolf, 2020), differential

attainment is observed on machine marked assessments too (Woolf et al., 2013).

Comparatively less has been reported on recruitment processes in UK medical specialty

recruitment.

Terms of reference and reporting

It was in the context described so far, that the REG commissioned Imperial College London in

late 2021 to independently:

1. Investigate the extent to which differential attainment may be present in the recruitment

process for Public Health specialty training; and

2. Make recommendations to mitigate any adverse impacts identified.

By this time, the REG had already introduced enhanced EDI monitoring for the 2021 cycle

recognising the need for better data to understand the problem. This report’s senior author made

recommendations for that data collection process in his position as a member of REG and

Technical Co-Lead for the Assessment Centre process in 2020.

a

Situational judgment tests are used widely in the selection of applicants in postgraduate medical

recruitment in the United Kingdom. Clinical assessments commonly involve providing a candidate with a

scenario after which they are invited to rank or select actions / responses (Koczwara et al., 2012).

8

This technical report and accompanying peer-reviewed publications form the outputs of this

commission.

Neither Health Education England (and its committees) nor the Faculty of Public Health had any

role in the analysis, reporting, recommendations or decision to submit findings presented in this

report or associated peer-reviewed publications. Owing to the timelines involved in peer-review,

the REG were given access to the findings ahead of public release.

This report is the work of the named authors who independently analysed the data and present

their recommendations.

9

Recruitment into Public Health Specialty Training

The Public Health Specialty Training recruitment process

Since the introduction of the current multi-stage process in 2009, Public Health recruitment has

extended from an England and Wales system, to incorporate Scotland, Northern Ireland, Defence

and Dental Public Health. As part of the preparation for the 2009 launch, detailed work was

undertaken to define the job description and person specification of the Specialty Registrar. The

intent was that the newly designed recruitment process would enable HEE to select the strongest

candidates into specialty training.

Candidates applying for specialty training in Public Health are assessed at three points to

determine whether they meet the person specification

b

and are appointable:

▪ Eligibility checking - candidates are required to demonstrate they meet the eligibility

criteria as set out in the person specification:

▪ Medical route: have completed a primary medical qualification, be eligible for full

registration with, and hold a current licence to practise from, the UK General

Medical Council (GMC), have a minimum of two years of postgraduate medical

experience (equivalent to the UK Foundation Programme) and have evidence of

having achieved foundation competencies in the last three years.

▪ BOTM route: have completed an undergraduate degree (1st or 2:1 or equivalent)

OR a higher certified degree (e.g. MSc, PhD), have at least 48 months of full time

work experience at the time of application, of which at least 24 months must be in

an area relevant to population health practice. The 24 months should be at Band

6 or above of Agenda for Change or equivalent, and a minimum of three months

at Band 6 or above should have been in the last three years.

All candidates who meet these criteria are then invited to the Assessment Centre

▪ Assessment Centre - candidates sit three psychometric tests over a period of

approximately three hours:

▪ Watson Glaser II Critical Thinking Appraisal (WGCTA II): a test of critical thinking

widely used across the world in recruitment to professional roles.

▪ Rust Advanced Numerical Reasoning Assessment (RANRA): a test of numerical

reasoning developed specifically for the UK market

▪ Situational Judgement Test (SJT): developed specifically for the Public Health

Specialty Training programme, this tests four characteristics from the person

specification (managing others and team involvement; professional integrity;

b

Person specification for 2023 recruitment round can be found at

https://specialtytraining.hee.nhs.uk/portals/1/Content/Person%20Specifications/Public%20Health/PUBLIC

%20HEALTH%20-%20ST1%202023.pdf

10

coping with pressure; organisation and planning).

In order to pass the Assessment Centre, candidates must achieve a standardised pass

score on all three tests.

For the 2022 cycle, to be invited to the Selection Centre, candidates must rank in the top 216

following Assessment Centre (or, for candidates eligible via the Disability Confident Scheme, pass

all three tests). The number of places at Selection Centre is broadly stable around 216 both prior

to and since the pandemic, but a reserve list is also sometimes called upon if candidates at or

above 216 withdraw. Rank is calculated based on an overall Assessment Centre score, with

Watson Glaser and RANRA weighted 25% each, and the SJT weighted at 50%.

▪ Selection Centre - until 2020 this was an in-person event held in Loughborough, and

assessed candidates via a written exercise, a group exercise and six mini-interviews

taking approximately three hours. Since 2021, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the

Selection Centre-equivalent has been held online, and the components reduced to a

single multi-question interview taking place over approximately 40 minutes.

At the end of the Selection Centre process, candidates are deemed appointable if they

pass a threshold score normally considered as 60% of the marks available in the Selection

Centre.

Those deemed appointable at Selection Centre are again ranked for a final recruitment score

comprising 60% of their score coming from Selection Centre, and 13.3% from each of the

Assessment Centre tests.

Posts are then offered to candidates, reflecting their location preferences as stated in their

application, starting with the top-ranked candidate and working down the list until all posts have

been filled.

The high-level process is summarised visually with approximate numbers (Figure 1).

As the number of applicants has grown (now exceeding 1000 candidates in the 2022 cycle), the

system has increasingly acted as a funnel with scrutiny increasing as candidates progress.

Accordingly, candidates are only deemed appointable after successfully completing all three of

these recruitment stages. It is likely that this bottleneck (constraining the numerator) and a very

large number of applicants applying but removed at earlier stages of the process (contributing to

the denominator) is part of the reason for the much lower percentages of candidates deemed

appointable (from both White and minority ethnic groups) cited in The BMJ analysis.

11

Figure 1. Funnel overview of the Public Health Specialty Training recruitment process,

extract from monitoring report (2021).

Existing actions undertaken to reduce the risk of differential attainment in

the process

Since its establishment, the REG has monitored the recruitment process and attempted to identify

groups which may be under-represented through the process.

In the first years after the establishment of the national recruitment process, the REG

commissioned an academic to assess the predictive validity of the new process, assessing scores

in recruitment against measures of progress through training. This analysis showed that higher

scores in the various parts of the recruitment process were associated with higher odds of passing

professional exams in training, and making satisfactory progress through training (assessed by

Annual Review of Competence Progression (ARCP) outcomes) (Pashayan et al., 2016). Related

(and unpublished) analysis by the private company who co-designed the 2009 process suggested

that the process demonstrated lower differential attainment than the regional processes it

replaced (Work Psychology Group, 2021).

There are various ways in which the REG, in designing and running the recruitment process, has

attempted to reduce the risk of differential attainment (Table 1).

12

Table 1. Existing measures to reduce the risk of differential attainment in the recruitment

process

Stage

Measures

Application

process

Public Health training is open to candidates from a wide range of professional

backgrounds, potentially increasing the diversity of the pool of applicants.

Since 2020 and inclusion on the UK Shortage Occupation List, the

recruitment into specialty training has been open to those requiring visa

sponsorship to work in the UK.

Eligibility

checking

Eligibility checkers are blinded to candidates’ name, age and sex. However,

they can identify country of primary qualification, location of work experience

and may be able to deduce age from other information provided. All eligibility

checkers are trained to ensure consistency in who is deemed eligible. All

applications are judged by two people independently, and a process exists

for resolving disagreements when these arise.

Assessment

Centre

Tests are the same for all candidates, regardless of professional background.

When introduced, all three tests were tested against existing measures (prior

to the introduction of a single national recruitment process) and found to

result in lower levels of differential attainment. Situational Judgement Tests

are developed through a rigorous process involving subject matter experts,

and tested and piloted before being used.

Selection

Centre

Interviewers are blinded to applicant’s background. Interviewers are required

to have undertaken Equality and Diversity training and Unconscious Bias

training. As far as possible, a diverse pool of interviewers is recruited

Each part of the process is marked by two or three assessors. Prior to the

pandemic at least 10 people assessed each candidate. Since the switch to

interview format, two people assessed each candidate in 2021 and three

people in 2022.

Process

overall

The recruitment process combines scores from a range of different types of

test, covering a range of competencies, to create a balanced overall score.

In 2020, ahead of the 2021 recruitment cycle, two additional voluntary questions were

incorporated into the initial application process designed to facilitate subsequent analysis for

possible residual confounders. The questions were designed to approximate language and

socioeconomic status.

The two questions posed were:

1. What is your main language?

Sourced from UK Census 2011 (Office for National Statistics, 2009)

13

2. What is the highest level of qualifications achieved by either of your parent(s) or

guardian(s) by the time you were 18?

Sourced from Cabinet Office paper on measuring proxies of socioeconomic status (HM

Government, 2018)

Furthermore, we also reviewed all medical applicants to identify whether they were UK trained or

non-UK trained (international medical graduate, IMG).

It is important to note that some medically qualified persons apply through the BOTM route due

to them not being able to fulfil the medical eligibility criteria – whether to do with recent clinical

competence or because they are not registered or eligible for a licence to practise in the UK. This

number is likely to be small, but the exact number is unknown. These candidates are categorised

in the following analyses as BOTM applicants.

14

Methods

Data extracts were provided to the analytical team by Health Education East Midlands. These

were partially redacted to fulfil data protection requirements on data minimisation. Four datasets

were provided, including applicant-level demographic and performance data across the four years

from 2018 to 2021 inclusive. Data were stored securely in-line with local information governance

requirements, and analyses were undertaken using STATA 17.0 for Mac.

The complexity of the recruitment process and potentially multiple (dependent variable) endpoints

necessitated a hypothesis-driven approach. Accordingly, and ex ante, a pre-specified descriptive

analysis and the following four hypotheses were selected following engagement with key

stakeholders:

H1. Lower success rates among non-White candidates reflected poorer performance by

International Medical Graduates

H2. Lower success rates among non-White candidates reflected a smaller proportion of

non-White candidates having English as a first language than White candidates

H3. Lower success rates among non-White and older candidates are confounded or

mediated by professional background

H4. Older candidates may have applied multiple times in the past and been unsuccessful

- could not be tested as data on the number of attempts made by candidates is not

collected.

The recruitment cycle interviews (termed ‘Selection Centre’) completed just as the pandemic

manifested in 2020. In-person interviews were not possible in 2021, meaning that the method of

selection changed. Accordingly, comparisons between the process up to 2020 and in 2021 and

beyond are not directly comparable. The 2021 recruitment cycle also collected the enhanced

equalities data. Therefore, two analytical cohorts were designated: the first covering the three

years 2018-2020 and the second, a single year snapshot of 2021.

The extracts were cleaned, collated and compiled into two cohorts for the analytical processes.

15

Findings

Preface

This report is underpinned by the peer-reviewed scientific papers that accompany it. Full methods

statements are included in those papers.

Please note that there are a very large number of potential endpoints that can be used to

characterise progression in this process.

Cohort sizes

There were 2430 applications to specialty training in the three years 2018 to 2020 inclusive (Table

2). For the second cohort (2021, involving the enhanced equalities monitoring), there were 984

applicants (Table 3).

Table 2. Descriptive breakdown of cohort by group, 2018-2020.

Application

year 2018

Application

year 2019

Application

year 2020

Total

applications

made

n

(%)

n

(%)

n

(%)

N

Total [%]

732

[30.1]

769

[31.7]

929

[38.2]

2430

Sex [%]

- Male

- Female

- Not disclosed

238

478

16

(32.5)

(65.3)

(2.2)

232

507

30

(30.2)

(65.9)

(3.9)

296

605

28

(31.9)

(65.1)

(3.0)

766

1590

74

Age group [%]

- ≤29

- 30-34

- 35-39

- 40-44

- 45+

- Not disclosed

229

211

159

73

60

-

(31.3)

(28.8)

(21.7)

(10.0)

(8.2)

218

207

171

84

70

19

(28.3)

(26.9)

(22.2)

(10.9)

(9.1)

(2.5)

261

275

184

101

77

31

(28.1)

(28.5)

(21.2)

(10.6)

(8.5)

(2.1)

708

693

514

258

207

50

Ethnicity [%]

- White British

- White Other

- Black

- Asian

- Mixed

- Chinese

- Other

- Not disclosed

346

84

84

119

37

8

11

43

(47.3)

(11.5)

(11.5)

(16.3)

(5.1)

(1.1)

(1.5)

(5.9)

390

66

80

113

25

16

19

50

(50.7)

(8.6)

(11.7)

(14.7)

(3.3)

(2.1)

(2.5)

(6.5)

455

81

112

155

43

13

18

52

(49.0)

(8.7)

(12.1)

(16.7)

(4.6)

(1.4)

(1.9)

(5.6)

1191

231

286

387

105

37

48

145

Professional

background [%]

- Medical

- BOTM

- Not disclosed

328

404

-

(44.8)

(55.2)

332

437

(43.2)

(56.8)

378

551

(40.7)

(59.3)

1392

1038

16

Table 3. Descriptive breakdown of cohort by group, 2021.

Application year 2021

n

(%)

Total

984

Sex [%]

- Male

- Female

- Not disclosed

315

641

28

(32.0)

(65.1)

(2.8)

Age group [%]

- ≤29

- 30-34

- 35-39

- 40-44

- 45+

- Not disclosed

306

269

165

115

77

52

(31.1)

(27.3)

(16.8)

(11.7)

(7.8)

(5.3)

Ethnicity [%]

- White British

- White Other

- Black

- Asian

- Mixed

- Chinese

- Other

- Not disclosed

438

90

123

170

57

13

38

55

(44.5)

(9.1)

(12.5)

(17.3)

(5.8)

(1.3)

(3.9)

(5.6)

Professional

background [%]

- UK Medical

- IMG

- BOTM

- Not disclosed

290

155

539

-

(29.5)

(15.8)

(54.8)

Highest parental

qualification

- No degree

- Degree

- Not disclosed

315

591

78

(32.0)

(60.1)

(7.9)

Main language

- English

- Not English

- Not disclosed

672

72

240

(68.3)

(7.3)

(24.4)

17

Analysis 1: Overall success rates by demographic group (2021)

To begin the analysis, we start high-level and examine the process from end-to-end. In this

analysis we use the term success rate:

c

success rate =

[candidates offered a post]

[

total candidates applied

]

− [candidates who withdrew their application]

In this analysis, we present the data broken down by demographic and professional

characteristics (Table 4). In 2021, the overall success rate was 15%

Graphs showing success rates for each group in 2018-2021 and 2021 are reported later

(Appendix A).

Analysis 1 identified suggests differential attainment, as the following groups were less

likely to be successful in recruitment to Public Health specialty training:

- Older candidates

- Non-white candidates, especially those from Black, Asian and Chinese

backgrounds

- International medical graduates and those from a background other than medicine

- Candidates who do not speak English as a first language

c

While mathematically not technically a ‘rate’, the term success rate is used as it appropriately describes the measurement

intended.

18

Table 4. Success rates by demographic group (2021 cohort)

Demographic

characteristic

Pattern seen in

recruitment in 2021

Was there evidence of differential attainment in

2021?

Sex

64% of successful

candidates are female

No. Male and female candidates are equally likely to be

successful:

- Male: 17%

- Female: 14%

(p=0.29, no statistically significant difference)

Age

83% of successful

candidates are under 35

years old

Yes. Success rate declines with increasing age

- Under 30: 25%

- 30-34: 17%

- 35-39: 10%

- 40-44: 3%

- Over 45: 5%

Ethnicity

79% of successful

candidates are White

Yes. Success rates varies by ethnicity

- White British: 22%

- White Other: 16%

- Asian: 6%

- Black: 4%

- Chinese: 9%

- Mixed: 21%

- Other: 13%

Overall, the “Mixed” category performs similarly to “White

British”

Professional

background

60% of successful

candidates are UK

Medical graduates, 3%

are IMG and 36%

BOTM

Yes. Success rates vary by professional background

- UK Medical graduates: 36%

- IMG: 4%

- BOTM: 9%

Primary

language

96% of successful

candidates reported

English as their primary

language (NB. data

were not available for

24% of candidates)

Yes. Success rates vary by first language

- English: 17%

- Not English: 8%

Highest

educational

qualification of

either parent

(SES proxy)

68% of successful

candidates had one or

more parent with a

degree level

qualification

No. Success rates did not vary by parental education

level

- No qualifications: 15%

- Qualifications below degree level: 14%

- Degree level or above: 16%

19

Analysis 2. Staged progression “pipeline”

On the back of findings that differential attainment appears to be present, we took a stage-by-

stage approach to identify at which point(s) the differential attainment may be arising.

A pipeline visualisation is used to present the demographic proportions at each point, running

from left to right. An example of this using ethnic groups for UK medical graduates only is

presented (Figure 2). Note that the numbers in each column fall from left to right, as some

candidates fail to progress to the next stage of recruitment.

Figure 2. Recruitment “pipeline” for UK Medical Graduates, by ethnicity (2021 cohort)

This initial analysis suggests that differential attainment by ethnic group appears to be operating

even within the sub-cohort of UK medical graduates, with White British candidates forming an

increasing share of the candidates left in the recruitment process at each stage except being

deemed eligible and being offered a post. Concurrently there a notable reduction in the share of

Black candidates at the Assessment Centre, and in Asian candidates being deemed appointable.

Full pipeline diagrams can be found in Appendix B. These cover the 2021 cohort only, but similar

patterns are observed for the 2018-2020 cohort, for those characteristics for which data are

available.

Analysis 2 identified that different groups are affected at different stages of the process,

but that the greatest impact is seen at the Assessment Centre stage. The largest variation

in likelihood to progress by age, ethnicity and professional background occurs at this

stage.

20

Analysis 3. Assessment Centre performance

Having identified that the most significant differential attainment by age, ethnicity and professional

background is observed in the Assessment Centre, we were interested to explore which

constituent tests, or combination of tests, might be driving the differential attainment.

As with success rates, performance on each psychometric test, and overall pass rates, were

examined by demographic group (Figure 3).

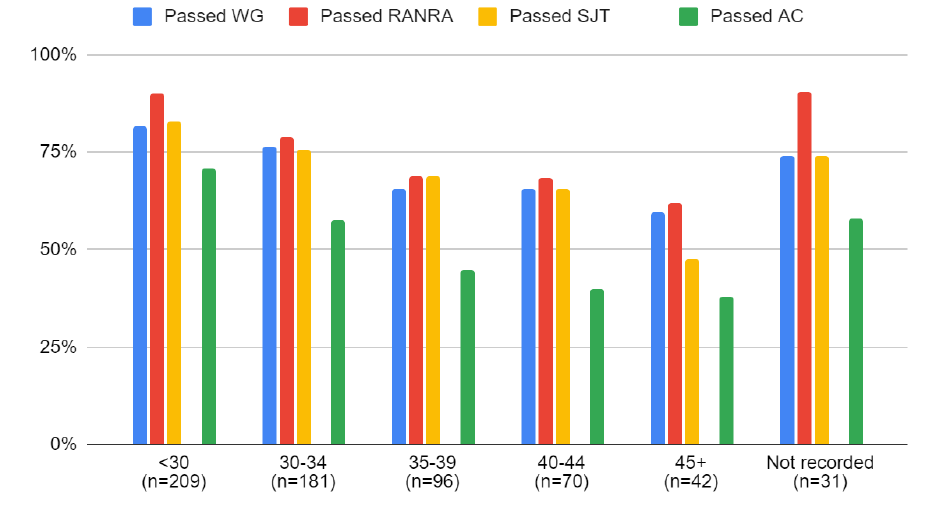

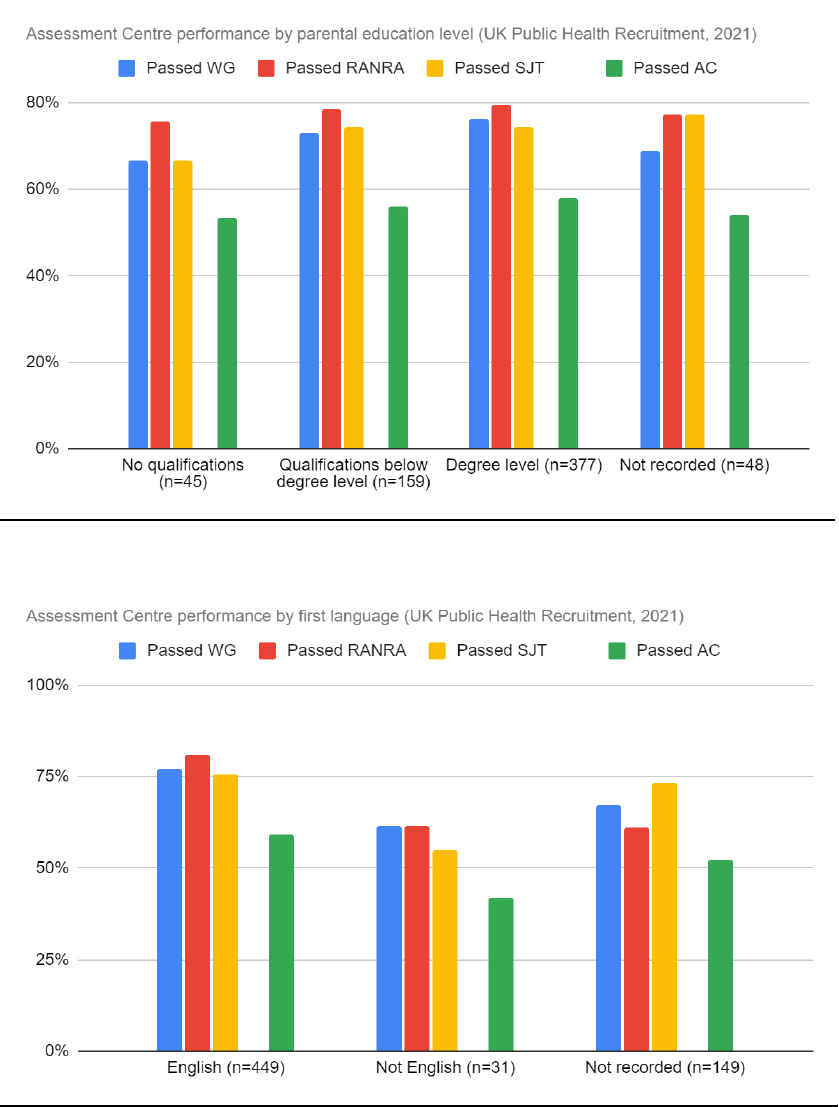

Figure 3. Assessment Centre performance by age (2021 cohort)

The full analysis can be found in Appendix C.

Analysis 3 determined that similar patterns of performance were observed across all three

psychometric tests. Groups which tend to have higher pass rates on one test also tend to

have higher pass rates on the other two. Black and Asian candidates, older candidates,

those who do not speak English as a first language and those from IMG and BOTM

backgrounds have lower overall success rates at the Assessment Centre.

21

Analysis 4. Multivariable analysis for assessment and selection

Multivariable logistic regression was undertaken for each of the cohorts against two endpoints

(dependent variables, see below). Odds ratios (OR) and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with

accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each demographic group at two

key stages of the process:

- Passing the Assessment Centre.

Note: that this is about passing the AC, not about ranking in the top 216 candidates to

progress.

- Being deemed appointable at the Selection Centre.

Note: that this is about passing the SC, not about ranking in the top 70+ places to secure

an offer of a post.

For the purposes of presenting these data, where p<0.05 the OR is presented, while findings that

did not achieve statistical significance (alpha = 0.05) are described as “NS” or not significant.

We found few differences between the OR and AOR calculated, suggesting that each of the

demographic characteristic variables is influencing success rates independently, and there is

comparatively little confounding (at least among the variables included) taking place (Table 5).

22

Table 5. Summary results from multivariable analysis

d

Demographic

characteristic

Passing the Assessment Centre

Deemed appointable

at Selection Centre

2018-2020

2021

2018-2020

2021

Sex

NS

NS

NS

NS

Age

With increasing

age, reduced odds

of success

With increasing

age, reduced odds

of success

Candidates 45+

reduced odds of

success

NS

Ethnicity

Black OR=0.10

Asian OR=0.24

Black OR=0.17

Asian OR=0.36

Chinese OR=0.27

White Other

OR=0.56

Asian OR=0.2

Background

BOTM OR=0.38

IMG OR=0.06

BOTM OR=0.2

NS

NS

First language

N/A

NS

N/A

NS

Parental education

N/A

NS

N/A

NS

Statistical note: The OR can be interpreted as [ 1.00 – (OR) = reduction in probability of achieving the specified endpoint ].

Therefore for an OR of 0.10, it means the group had a 90% lower probability of passing AC or being deemed appointable at SC.

Analysis 4 identified statistically significantly lower probability of passing the Assessment

Centre for the following groups:

- Older candidates, with each older age band having lower likelihood of success than

the last

- Black and Asian candidates

- Chinese candidates (2021 analysis only) – note small numbers

- International medical graduates and candidates from a background other than

medicine

The analysis also identified statistically significantly lower likelihood of being deemed

appointable at Selection Centre for the following groups:

- Candidates aged over 45 (2018-2020 analysis)

- White Other candidates (2018-2020 analysis)

- Asian candidates (2021 analysis) – note small numbers

d

NS = No statistically significant differences found; N/A = this data was not collected in this period.

Reported odds ratios are unadjusted.

Reference groups were:

- Age: under 30

- Ethnicity: White British

- Background: UK Medical Graduates

- First language: English

23

Summary of findings from Public Health recruitment data

The analyses outlined above were used to test the three hypotheses (H) formulated at the start

of our research:

H1. Lower success rates among non-White candidates reflect poorer performance by

International Medical Graduates

▪ International Medical Graduates have the lowest success rate of the three

professional groups.

▪ However, within the UK Medical Graduate group, which has the highest overall

success rate, non-White candidates have lower success rates

H2. Lower success rates among non-White candidates reflect a smaller proportion of non-White

candidates having English as a first language than White candidates

▪ Candidates who speak a language other than English as their first language

have lower success rates than those who speak English as their first language

▪ However, within the group of candidates who speak English as a first language,

non-White candidates have lower success rates

H3. Lower success rates among non-White and older candidates are confounded or mediated

by professional background

▪ For example, UK Medical Graduates tend to be younger than BOTM candidates,

and tend to have higher success rates, so professional background could be

confounding the relationship between age and success.

▪ However, analysis within each professional group shows the same patterns of

lower success rates for non-White candidates and candidates aged over 35.

None of the hypotheses can either fully or collectively explain the differential attainment observed

in these analyses.

Put together, the analyses provide evidence that some demographic groups, especially

older candidates, Black and Asian candidates and candidates who are not UK medical

graduates, are less likely to be successful in recruitment to Public Health specialty

training.

This attainment gap is most marked at the Assessment Centre stage of the process, and

persists in multivariable analysis, suggesting that age, ethnicity and professional

background each are independently associated with a candidate’s likelihood of success.

24

Discussion

The analyses enable us to describe patterns of differential attainment. However, the findings

cannot explain the drivers of such patterns. To try to understand this, and what options might be

practicable and effective, we undertook a rapid literature review, with particular focus on

psychometric testing.

We focused on psychometric testing because:

▪ The most marked differential attainment in the Public Health specialty training recruitment

process is apparent the Assessment Centre, both in proportional and numerical terms.

▪ More intuitive explanations for differential attainment, such as bias by interviewers, do not

appear to explain the patterns observed.

The published literature reveals similar patterns of attainment by age and ethnicity to those

observed in Public Health specialty training recruitment. The Assessment Centre is provided by

Pearson Vue, a commercial testing and certification provider operating internationally. Pearson

Vue’s own literature on the Watson Glaser Critical Thinking Assessment reports that language,

age and especially ethnicity have been previously associated with differential group performance

on the test, but argues that following up the cohorts, there was no difference between groups

when predicting progression in-role (Pearson, 2020). Similar patterns are observed in other

cognitive ability tests (Hough et al., 2001). In associated technical documentation, it is

recommended that local implementation organisers validate attainment in their own cohorts

(Watson & Glaser, 2010).

Equivalent evaluation evidence for the RANRA test was not available, although suggestion is

made in the technical guidance that local implementors give due to consideration for candidates

with English as a second language, as the RANRA test is predicated on proficient English (Rust,

2006).

The Situational Judgment Test for Public Health is a bespoke assessment with development led

by Work Psychology Group who validate items co-developed with Public Health specialists on a

rolling basis. Annual reporting is provided back to the REG which includes analysis of group

performance. There has been a consistent pattern of differential performance by ethnicity and

professional group in those reports.

In summary, the evidence from the literature available on cognitive testing suggests that ethnic

and age differences are at best not unusual and, at worst, commonplace (Hough et al., 2001).

The causes of differential attainment in psychometric testing are unknown, although a number of

hypotheses have been proposed:

▪ Differential access to networks of people who can support preparation for the recruitment

process

▪ Differential familiarity with psychometric testing generally, and the specific tests used

25

(Hinton, 2014)

▪ Test taker perception (candidates perform better on tests which they perceive to have

higher criterion validity) (Hough et al., 2001)

▪ Test taker concern or stereotype threat (poorer performance by candidates who belong

to groups who are not expected to perform well on tests)

(Steele, 1997)

▪ Structural racism as experienced throughout the life-course (in education and more

broadly)

Of interest, tests focusing on other domains have been shown to have different patterns of

differential attainment. For example, tests of emotional intelligence, interpersonal skills and

performance on real job tasks, have be found to show less differential attainment or even favour

minoritised groups and older candidates (Hough et al., 2001).

A number of approaches have been taken in other recruitment settings to try to overcome historic

differential attainment:

▪ The Royal College of Midwives has developed their programme Turning the Tide which

offers mentoring and interview preparation for non-White midwives to support their career

progression

▪ A commercial recruitment specialising in improving workplace diversity, Rare Recruitment

has developed a process for contextualising the academic achievements of graduates

from less traditional backgrounds, enabling them to access elite graduate schemes, for

example in law firms.

▪ Rare Recruitment also offers internships and coaching to support non-White candidates

to prepare for the selection processes of specific employers, including Civil Service Fast

Stream. Such schemes produce substantial improvements in the likelihood of candidates

being successful (Rare Recruitment, 2012)

While this is the largest and most comprehensive analysis to date on these data, there are

inherent limitations to this analytical process. Even with the aggregation of multiple years’ data,

the findings are limited by comparatively small group sizes for minoritised groups. The analytical

mitigation was to aggregate ethnic groups which consequently risks masking underlying

differences between more precise ethnic groups.

The enhanced equalities monitoring questions were introduced in the 2021 recruitment cycle (and

have been retained for 2022 onwards). However, we note no positive findings for either of the two

new questions. Like the other negative findings, the possibility of a type II error cannot be

discounted (where the absence of a finding does not mean the absence of an effect).

The risks of misclassification have already been highlighted. The findings of differential attainment

for IMG are stark and consistent with patterns observed elsewhere. It is likely that there are IMGs

and possibly UK trained doctors misclassified as BOTM and future data collection should focus

on capturing this variable more accurately.

26

Finally, because the numbers reduce as the process advances, the statistical power to identify

issues at the Selection Centre stage is less than that at earlier stages of the process. While we

are confident that differential attainment appears more attributable to the Assessment Centre than

the Selection Centre, we also cannot rule out differential attainment occurring at the Selection

Centre. The implication of this is that attention should continue on ensuring an EDI-informed

approach among assessors.

27

Options for action

These analyses point to the need for action to be taken to ensure the Public Health specialty

training recruitment process is fair for all applicants, and to ensure that Public Health as a

discipline does not lose excellent candidates because of the design of the selection process.

Possible options for action should be considered in the context of the following points:

▪ Pragmatism is vital. It is not sufficient to criticise an existing process if no better process

can be selected to replace it.

▪ The recruitment process involves hundreds of applicants each year meaning that solutions

need to be scalable.

▪ That the specialty recruitment process is part of a wider system and does not exist in

isolation; while the REG has the power to determine the process end-to-end through the

recruitment, we must recognise that options may need to be considered pre-application

and across a range of organisations and institutions and outside the HEE’s sphere of

control.

There are two further complications:

▪ Continued evidential uncertainty about the root causes of the differential attainment.

▪ The absence of ready-made solutions which could be adopted by the REG.

In light of this uncertainty, a range of options are presented chronologically (Figure 4) for

consideration (Table 6). Not all may be practical or desirable, and the risks associated with

different options are not explicitly explored. However, in the context of this report’s analyses,

doing nothing is unlikely to remain an option.

28

Figure 4. Stages of the recruitment process and areas for action

29

Table 6. Options appraisal

Areas for action

Options for action include…

1. The decision to apply

1.1 Provide universal

information and advice

prior to application

▪ Advertise and operate a national webinar prior to application

deadline, or for all those who have applied, to explain the

recruitment process and answer any questions.

▪ Provide all candidates with more information about the

Assessment Centre tests, including sample questions and model

answers with rationale.

▪ Review where training posts are advertised to increase awareness

of the recruitment opportunity

1.2 Provide targeted

support to candidates

▪ Develop a package of support focused specifically on the

recruitment process available to members of groups known to be

disadvantaged by the current process. For example, Black and

Asian candidates who were deemed eligible but not appointable in

Year 1, could be offered additional support before re-applying in

Year 2.

▪ Provide general coaching and / or mentoring support available to

members of groups known to be disadvantaged by the current

process.

2. Assessment Centre

2.1 Amend “cut scores” for

Assessment Centre tests

▪ Lower the cut scores (pass marks) for Assessment Centre tests

would increase the number of candidates eligible to attend the

Selection Centre (Pearson, 2020). However, this is likely to have

a limited impact on differential attainment unless the number of

Selection Centre slots were increased, since there are already

more candidates who pass the Assessment Centre than can be

invited to the Selection Centre, so only those with the highest

ranking proceed.

e

▪ Implement different cut scores for different groups, to reflect

established differences in performance such as those identified in

Pearson’s assessment of the Watson Glaser test.

2.2 Amend, replace or

eliminate the

psychometric tests used

at Assessment Centre

▪ Identify psychometric tests that measure the same domains

(critical thinking, numerical reasoning and situational judgement)

but show lower differential attainment than those currently used,

and either piloting them alongside existing tests or replacing

existing tests

▪ Include psychometric tests that measure different domains that

have been shown to have different patterns of differential

attainment compared with those currently used e.g. tests of social

and emotional intelligence

▪ Identify tests used by other organisations e.g. Civil Service Fast

Stream which has moved away from using generic psychometric

e

Sensitivity analysis was undertaken to assess the potential impact of changes to both cut scores and the weighting of the different

psychometric tests, and none of the changes trialled were found to significantly reduce differential attainment by ethnicity, although

there were some improvements for older candidates and those from a background other than medicine. This appeared to be a by-

product of the mismatch between candidates passing AC and the limited 216 places at SC.

30

tests and is likely to be monitoring the effect of this change on

differential attainment. It may be that these organisations are

willing to share the tests with HEE for use for Public Health

recruitment.

2.3 Replace the

Assessment Centre with

another shortlisting

approach

▪ Identify alternative ways to reduce the number of candidates to

the 216 who can be accommodated at the Selection Centre. It

should be noted that other approaches, such as scoring CVs,

would be fundamentally different from the existing approach,

which aims to measure only potential to benefit from training, and

not prior experience in Public Health.

3. Selection Centre

3.1 Increase the number

of candidates invited to

Selection Centre

▪ Differential attainment is lower at the Selection Centre than the

Assessment Centre, suggesting that allowing more candidates to

reach the Selection Centre stage could reduce differential

attainment. However, there would be cost and logistical

implications for any increase in Selection Centre places, and at

present Assessment Centre scores are still used in the final

ranking of candidates, so could continue to disadvantage some

groups of candidates.

4. Research, analysis and evaluation

4.1 Continue to collect

and analyse additional

demographic information

from all candidates

▪ Continue to collect information on parental education and main

language, and ensure data on disability (which is already

collected) is available for future analysis of differential attainment

▪ Improve monitoring to capture those with medical qualifications

applying through the Background Other Than Medicine route, to

determine whether these candidates have a distinct profile

alongside the other professional background groups, and country

of Primary Medical Qualification for any candidates with medical

degrees.

4.2 Conduct further

research to understand

the drivers of differential

attainment

▪ Seek input from subject matter experts to identify opportunities to

reduce differential attainment in the recruitment process. This

might include other recruiters e.g. Civil Service Fast Stream, or

experts within recruitment consultancies

4.3 Analyse the results of

the “Leaky pipeline”

survey carried out in 2021

▪ The “Leaky pipeline” survey of current Registrars was undertaken

by the Faculty of Public Health’s Equality and Diversity Special

Interest Group in 2021 but has not yet been analysed. It focused

on experiences of applying for Specialty Training and may include

insights which could be used to inform the development of the

recruitment process to reduce differential attainment

4.4 Monitor and evaluate

the impact of any changes

to the recruitment process

▪ Consider piloting new approaches before adopting them

permanently

▪ Ensure resources are available to monitor the impact of any

changes to the recruitment process

31

Recommendations for the Recruitment Executive Group

This report has identified that specific groups appear to be disadvantaged by the current

recruitment process. The reasons for this differential attainment are complex and not fully

understood. Any changes implemented need to recognise this uncertainty. Any such changes

also need to recognise that the current system has many features designed to reduce the risk of

differential attainment, and has been demonstrated to be effective at predicting success in key

milestones during training.

We recommend action should be taken in three key areas, in parallel:

Recommendation 1

Undertake a comprehensive review of the job analysis, person specification and

selection process

We recommend that an external organisation with expertise in recruitment processes and

equality and diversity considerations should be commissioned to review each of the key

components of the recruitment process. This should involve refreshing the job analysis (last

reviewed in 2009), updating the person specification accordingly, and then reviewing the

selection process.

We do not expect that updating the job analysis alone will have an impact on differential

attainment. However, this is a necessary foundation upon which any new or modified

selection process should be built. This work is vital in being able to determine what questions

may deemed acceptable in the Situational Judgment Test component in particular.

Given the findings of the review, particular care should be given to designing a process which

reduces the likelihood of differential attainment by ethnicity or age.

Recommendation 2

Initiate shorter-term actions to mitigate the risks associated with the current process

While the more comprehensive review work is being undertaken, there are a number of

shorter-term actions that can be pursued to mitigate the risks associated with the current

process. These should include the following options (outlined in more detail in Table 5):

▪ Provide universal information and advice around the point of application: whether prior

to applications closing, following the point of application, or again at various points

within the process.

▪ Explore opportunities to provide targeted support to candidates from disadvantaged

groups. This may require piloting and evaluating how such candidates can be

32

identified and subsequently supported. It may be that the Faculty of Public Health is

best placed to co-ordinate this.

Recommendation 3

Continue monitoring, evaluation and research to better understand, support and refine

the process

Any options pursued by the REG should be accompanied by continuing monitoring and evaluation

to assess their impact on differential attainment, as well as identifying any unintended

consequences. This evaluation should be built in from the start, and should include the following

options:

▪ Continue to collect and analyse additional demographic information from all candidates

▪ Conduct further research to understand the drivers of differential attainment

▪ Analyse the results of the “Leaky pipeline” survey carried out in 2021

▪ Monitor and evaluate the impact of any changes to the recruitment process

Conclusion

Our findings provide strong evidence that differential attainment is present in the current Public

Health specialty training recruitment process. While we acknowledge the strengths of the system

in providing a scalable, multi-point assessment of candidate potential which correlates well with

future performance, we must recognise its deficiencies.

The existing process appears to select strong candidates. Yet at the same time, it appears to

disadvantage candidates from several groups: those from minority backgrounds, those who are

older, and those from international medical graduate backgrounds and backgrounds other than

medicine.

Future improvements must take care to avoid losing the positives in attempts to mitigate the

negatives. However, action is needed to create a more level playing field and ensure that the

Public Health specialty can deliver on its commitment to a fairer and more equal future.

33

References

General Medical Council. (2022). What is differential attainment? https://www.gmc-

uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula/projects/differential-attainment/what-is-

differential-attainment

Gupta, A., Varma, S., Gulati, R., Rishi, N., Khan, N., Shankar, R., & Dave, S. (2021). Differential

attainment in undergraduate medical education: a systematic review. BJPsych Open,

7(Suppl 1), S27. https://doi.org/10.1192/BJO.2021.128

Hinton, D. P. (2014). Uncovering the root causes of ethnic differences in ability testing:

Differential test functioning, test familiarity and trait optimism as explanations of ethnic

group differences.

HM Government. (2018). Annex A - Evaluation of measures of socio-economic background.

Hough, L. M., Oswald, F. L., & Ployhart, R. E. (2001). Determinants, Detection and Amelioration

of Adverse Impact in Personnel Selection Procedures: Issues, Evidence and Lessons

Learned. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9(1–2), 152–194.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2389.00171

Iacobucci, G. (2020). Specialty training: ethnic minority doctors’ reduced chance of being

appointed is “unacceptable.” BMJ, 368, m479. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.M479

Koczwara, A., Patterson, F., Zibarras, L., Kerrin, M., Irish, B., & Wilkinson, M. (2012). Evaluating

cognitive ability, knowledge tests and situational judgement tests for postgraduate

selection. Medical Education, 46(4), 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1365-

2923.2011.04195.X

McManus, I. C., & Wakeford, R. (2014). PLAB and UK graduates’ performance on MRCP(UK)

and MRCGP examinations: Data linkage study. BMJ (Online), 348.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g2621

Office for National Statistics (UK). (2009). Finalising the 2011 questionnaire - Office for National

Statistics.

https://www.ons.gov.uk/census/2011census/howourcensusworks/howweplannedthe2011ce

nsus/questionnairedevelopment/finalisingthe2011questionnaire

Pashayan, N., Gray, S., Duff, C., Parkes, J., Williams, D., Patterson, F., Koczwara, A., Fisher,

G., & Mason, B. W. (2016). Evaluation of recruitment and selection for specialty training in

public health: interim results of a prospective cohort study to measure the predictive validity

of the selection process. Journal of Public Health, 38(2), e194–e200.

https://doi.org/10.1093/PUBMED/FDV102

Patterson, F., Tiffin, P. A., Lopes, S., & Zibarras, L. (2018). Unpacking the dark variance of

differential attainment on examinations in overseas graduates. Medical Education, 52(7),

736–746. https://doi.org/10.1111/MEDU.13605

Pearson. (2020). Watson Glaser Efficacy Report. https://us.talentlens.com/resources/watson-

glaser-efficacy-report.html

Rare Recruitment. (2012). Diversity Graduate Recruitment.

https://www.rarerecruitment.co.uk/news/civil-service-programme-bags-best-diversity-award

Rust, J. (2006). Advanced Numerical Reasoning Appraisal TM (ANRA) Manual.

34

Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air. How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and

performance. The American Psychologist, 52(6), 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-

066X.52.6.613

Tiffin, P. A., & Paton, L. W. (2021). Differential attainment in the MRCPsych according to

ethnicity and place of qualification between 2013 and 2018: a UK cohort study.

Postgraduate Medical Journal, 97(1154), 764–776.

https://doi.org/10.1136/POSTGRADMEDJ-2020-137913

Watson, G., & Glaser, E. M. (2010). Watson-Glaser TM II Critical Thinking Appraisal Technical

Manual and User’s Guide. www.TalentLens.com

Woolf, K. (2020). Differential attainment in medical education and training. BMJ (Clinical

Research Ed.), 368. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.M339

Woolf, K., Mcmanus, I. C., Potts, H. W. W., & Dacre, J. (2013). The mediators of minority ethnic

underperformance in final medical school examinations. The British Journal of Educational

Psychology, 83(Pt 1), 135–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.2044-8279.2011.02060.X

Work Psychology Group. (2021). Personal communication.

35

Appendices

Appendix A. Detailed results from Analysis 1: Success rates

Success rates were calculated as follows:

success rate =

[candidates offered a post]

[

total candidates applied

]

− [candidates who withdrew their application]

In 2021, 984 candidates applied, 775 did not withdraw and 118 were offered posts, giving an

overall success rate of 15%.

Success rates by age

Success rates by sex

36

Success rates by professional background

Success rates by ethnicity

All four cohorts were analysed together by reported ethnicity, rather than the condensed

categories used elsewhere in this report. Between 2018 and 2021, no candidates from

Bangladeshi (n=21), Mixed White and Black African (n=32) or Any Other Black (n=18)

backgrounds were successful in public health specialty training recruitment:

37

Success rates by parental education (proxy for socio-economic status) (2021 only)

Success rates by first language (2021 only)

38

Appendix B. Detailed results from Analysis 2: Staged progression pipeline

Pipeline diagram by age

Pipeline diagram by sex

39

Pipeline diagram by professional background

Pipeline diagram by ethnicity

40

Pipeline diagrams by ethnicity and professional background

NB the diagram for International Medical Graduates is not presented here as the number of

successful candidates is too small to be able to draw meaningful conclusions, and the small

numbers mean candidates would be potentially identifiable.

41

Pipeline diagram by parental education

Pipeline diagram by first language

42

Pipeline diagram by ethnicity and first language

43

Appendix C. Detailed results from Analysis 3: Assessment Centre

performance

Assessment Centre performance by age

Assessment Centre performance by sex

44

Assessment Centre performance by professional background

Assessment Centre performance by ethnicity

45

Assessment Centre performance by parental education

Assessment Centre performance by first language