EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

Land-Use Planning & Development Control:

Planning For Air Quality

www.iaqm.co.ukwww.environmental-protection.org.uk

Guidance from Environmental Protection UK and the Institute of Air Quality Management for the

consideration of air quality within the land-use planning and development control processes.

January 2017

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

2

Contents

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

Acknowledgements 3

Record of substantive amendments 4

1. Purpose and structure of this guidance 6

2. The Role of the Planning Regime 8

3. Links between poor air quality, human health and the environment 9

4. Planning Framework 11

Policy context 11

Supplementary Planning Documents and Guidance 12

The Planning Process 12

Material Considerations 12

Air quality as a material consideration 13

Linkages with other relevant issues 13

5. Better by design 14

Introduction 14

Overarching Concepts in Land Use Planning for Better Air Quality 14

Making Better Use of the Land-use Planning System 14

Examples of Approaches to Reducing Emissions and Impacts 16

Principles of Good Practice

17

Offsetting Emissions 18

6. Undertaking an Air Quality Assessment 19

Purpose 19

The need for an air quality assessment 19

Impacts of the Local Area on the Development 20

Impacts of the Development on the Local Area 21

Content of an air quality assessment 22

Agreement of datasets and methodologies 24

Describing the impacts 26

7. Assessing Significance 29

8. Mitigating Impacts 31

Abbreviations and acronyms 32

Table 4.1: Context of air quality and planning in England. 12

Table 6.1: Stage 1 Criteria 20

Table 6.2: Indicative criteria for requiring an air quality assessment 21

Table 6.3: Impact descriptors for individual receptors 25

Figure 1: Procedure for Evaluating New Developments 7

Figure 2: Role of Local Authority and Applicant/Developer in the planning process 15

Box 1: Examples of Approaches to Reducing Emissions and Impacts 14

EPUK & IAQM Land-Use Planning & Development Control: Planning For Air Quality 3

Acknowledgements

Disclaimer: This guidance was produced as a result of the

voluntary contribution of individuals within the Working

Group, who are members of EPUK and/or IAQM, for which

both organisations are grateful. Whilst this guidance represents

a consensus view of the Working Group, it does not necessarily

represent the view of individual members.

The information in this document is intended to provide

guidance for those working in land-use planning and

development control, and does not constitute legal advice.

The IAQM and EPUK have endeavoured to ensure that all

information in this document is accurate. However, neither

organisation will accept liability for any loss, damage or

inconvenience arising as a consequence of any use of or the

inability to use any information in this guidance. We are not

responsible for any claims brought by third parties arising from

your use of this Guidance.

Chairs of the Working Group

Stephen Moorcroft, Air Quality Consultants

Roger Barrowcliffe, Clear Air Thinking

Members of the Working Group

Paul Cartmell, Lancaster CC

Mark Chapman, Jacobs

Ben Coakley, Chiltern DC

Beth Conlan, Ricardo-AEA

Ana Grossinho, Air Quality Experts Global Ltd

Graham Harker, Peter Brett Associates

Claire Holman, Brook Cottage Consultants

Nigel Jenkins, Sussex AQ Partnership

Marilena Karyampa, Arup

Julie Kent, Rotherham MBC

Rachel Kent, Wiltshire DC

Duncan Laxen, Air Quality Consultants

Oliver Matthews, Carmarthenshire Council

Fiona Prismall, RPS Planning & Development

Rebecca Shorrock, Cheshire East Council

Claire Spendley, South Oxfordshire DC

Stuart Stearn

Alex Stewart, Public Health England

Adrian Young, Environment Agency

Environmental Protection UK: Environmental Protection UK

is a national charity that provides expert policy analysis and

advice on air quality, land quality, waste and noise and their

effects on people and communities in terms of a wide range of

issues including public health, planning, transport, energy and

climate. Membership of Environmental Protection UK is drawn

from local authorities, industry, consultancies and individuals

who are practicing professionals in their field, or have an interest

in the environment.

The Institute of Air Quality Management (IAQM): IAQM

aims to be the authoritative voice for air quality by maintaining,

enhancing and promoting the highest standards of working

practices in the field and for the professional development of

those who undertake this work. Membership of IAQM is mainly

drawn from practising air quality professionals working within

the fields of air quality science, air quality assessment and air

quality management.

Graphic Design: Darren Walker (darrengraphidesign.com)

Copyright statement: Copyright of these materials is held by

the members of the Working Group. We encourage the use of

the materials but request that acknowledgement of the source

is explicitly stated. All design rights are held by the IAQM, unless

otherwise stated.

Suggested citation: Moorcroft and Barrowcliffe. et al. (2017)

Land-use Planning & Development Control: Planning for Air

Quality. v1.2. Institute of Air Quality Management, London.

Contact: IAQM

c/o Institution of Environmental Sciences

3rd Floor, 140 London Wall, London

EC2Y 5DN

T: +44 (0)20 7601 1920

Date: January 2017

Cover image: © Stanko07 | Dreamstime.com

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

4

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

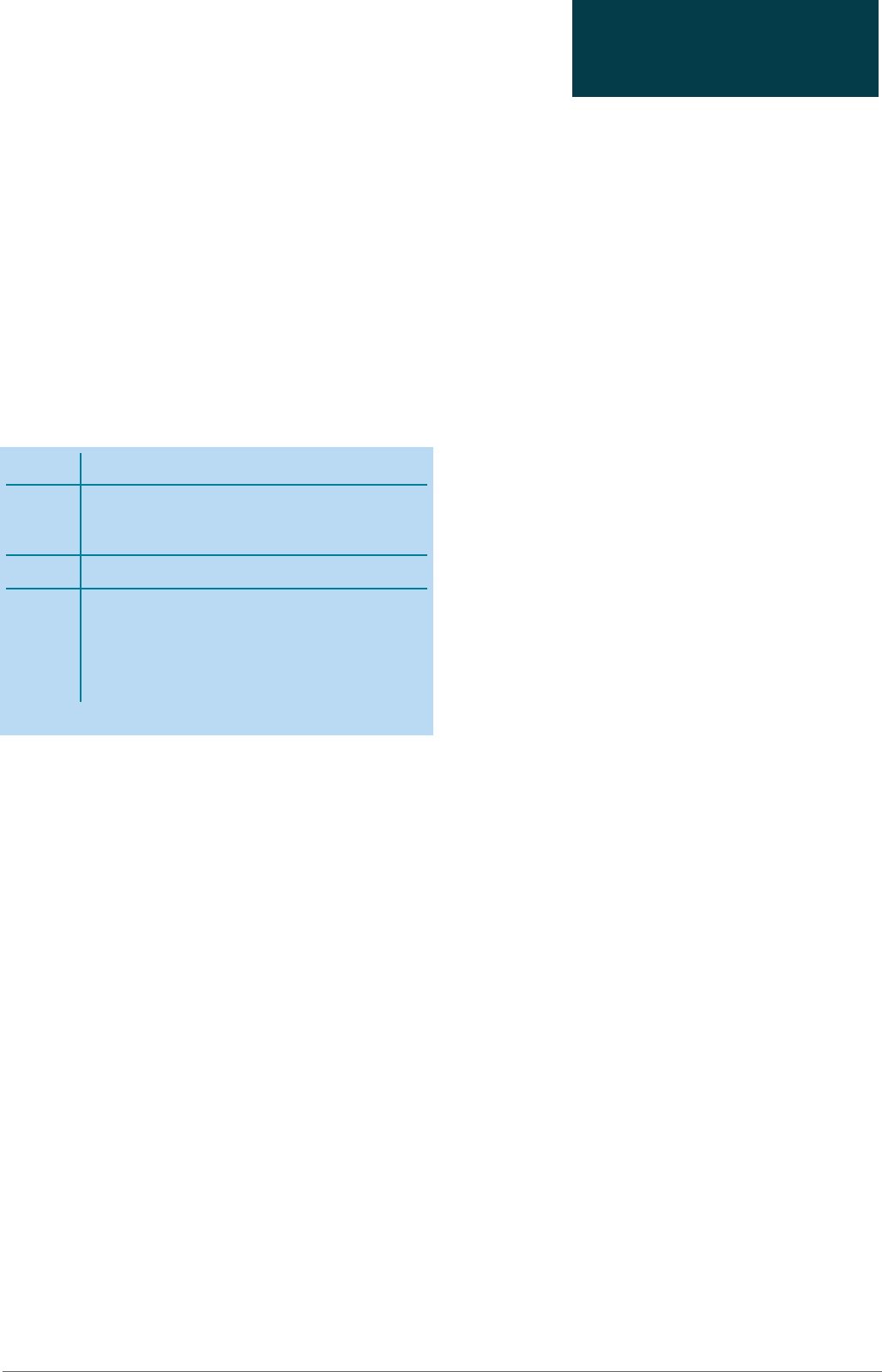

Record of substantive amendments

Original

location

Revised

location

Amendment made

Throughout

--- Reference to LAQM TG (09) updated to reflect the Technical Guidance issued in 2016

Throughout

--- Reference to the Environment Agency’s H1 methodology updated to reflect the withdrawal of this guidance

and its replacement in February 2016.

1.9 1.9 Replacement paragraph as follows: This guidance could be adapted for use in the Scottish and/or Northern

Ireland planning systems, because it is considered that the general principles of air quality assessment set

out herein are applicable in all parts of the United Kingdom.

3.4 3.4

Replacement final sentence: The Committee recommends that concentration response functions for the

association between NO

2

and premature mortality can be used, with some qualifications [footnote]. When

applied on a national basis, use of these functions suggests that the national premature mortality burden

for long term exposure to NO

2

is equivalent to 23,000 deaths annually [footnote].

New footnote: www.gov.uk/government/publications/nitrogen-dioxide-interim-view-on-long-term-

average-concentrations-and-mortality

New footnote: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/486636/aq-

plan-2015-overview-document.pdf

6.3 6.4 Additional paragraph: The guidance provided by the Environment Agency and Highways England has a

formal status, reflecting the connections these organisations have with Government departments. This

EPUK/IAQM guidance has no such status and is not intended as a substitute for the formal guidance.

6.8 6.9 Additional text: The use of a Simple Assessment may be appropriate, where it will clearly suffice for

the purposes of reaching a conclusion on the significance of effects on local air quality. The principle

underlying this guidance is that any assessment should provide enough evidence that will lead to a sound

conclusion on the presence, or otherwise, of a significant effect on local air quality. A Simple Assessment

will be appropriate, if it can provide this evidence Similarly, it may be possible to conduct a quantitative

assessment that does not require the use of a dispersion model run on a computer.

6.9 6.10 Amended text: The criteria provided are precautionary and should be treated as indicative. They are

intended to function as a sensitive ‘trigger’ for initiating an assessment in cases where there is a possibility

of significant effects arising on local air quality. This possibility will, self-evidently, not be realised in many

cases. The criteria should not be applied rigidly; in some instances, it may be appropriate to amend them

on the basis of professional judgement, bearing in mind that the objective is to identify situations where

there is a possibility of a significant effect on local air quality.

Additional text: In certain circumstances, it may be necessary to consider whether the site itself is suitable

for the introduction of new emission sources. This could be because the neighbouring land use has

particular sensitivities to increased exposure to air pollutants. It is not possible, or desirable, to set criteria

that would define such circumstances. In practice, it is more likely that an assessment would reach a

conclusion taking any local factors into account.

Original

location

Revised

location

Amendment made

Table 6.2;

row 7

Table 6.2;

row 7

‘kWh’ corrected to ‘kW’

v1.1. June 2015

v1.2. January 2017

EPUK & IAQM Land-Use Planning & Development Control: Planning For Air Quality 5

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

Original

location

Revised

location

Amendment made

6.14 6.16 Additional text: The principle underlying this guidance is that any assessment should provide enough

evidence that will lead to a sound conclusion on the presence, or otherwise, of a significant effect on local

air quality. A Simple Assessment will be appropriate, if it can provide this evidence.

Table 6.2 Table 6.2 Rows 7 and 8 merged.

Replacement text in left hand column: Have one or more combustion processes, where there is a risk of

impacts at relevant receptors.

NB. this includes combustion plant associated with standby emergency generators (typically associated

with centralised energy centres) and shipping.

Replacement text in right hand column: Typically, any combustion plant where the single or combined

NOx emission rate is less than 5 mg/sec is unlikely to give rise to impacts, provided that the emissions are

released from a vent or stack in a location and at a height that provides adequate dispersion.

In situations where the emissions are released close to buildings with relevant receptors, or where the

dispersion of the plume may be adversely affected by the size and/or height of adjacent buildings (including

situations where the stack height is lower than the receptor) then consideration will need to be given to

potential impacts at much lower emission rates.

Conversely, where existing nitrogen dioxide concentrations are low, and where the dispersion conditions are

favourable, a much higher emission rate may be acceptable.

6.32 6.33 Additional text: Users of the impact descriptors set out in Table 6.3 are encouraged to follow the

explanatory notes carefully and recognise the spirit in which they apply. In particular, the intention is that

the descriptors should not be applied too rigidly and assessors should recognise the inevitable uncertainties

embedded within the process of their determination.

6.33 6.34 Replacement text: Most particulate matter from combustion processes (including road traffic) occurs in

the PM

2.5

fraction. The AQAL for PM

2.5

is lower than that for PM

10

, and this therefore represents the more

conservative approach for these sources. The application of Table 6.3 for PM

2.5

is straightforward, given

that the AQAL is expressed as an annual mean. In assessing road traffic sources, however, regard must also

be given to emissions from brake/tyre wear and road abrasion, which are predominantly in the 2.5-10

μm

fraction. Consequently, PM

10

is the more appropriate pollutant to assess in these circumstances. For the

assessment of PM

10

, Table 6.3 should be applied using an AQAL of 40 μg/m

3

as an annual mean; in addition,

consideration should also be given to the daily mean AQAL. This can be done using a derived value for the

annual mean based on the number of days exceeding a daily mean concentration of 50

μg/m

3

being no

more than 35 times per year. (The equation in LAQM.TG16 shows an annual mean of 32

μg/m

3

equating to 35

days at or above 50

μg/m

3

).

6.37 6.38 Deleted text: It is preferred that the annual mean AQAL is used for this pollutant.

6.38 6.39 Amended text: Where such peak short term concentrations from an elevated source are in the range 101-

20% of the relevant AQAL, then their magnitude can be described as small, those in the range 20

1-50%

medium and those above 50

1% as large.

7.7 7.8 Additional paragraph: The population exposure in many assessments will be evaluated by describing the

impacts at individual receptors. Often, these will be chosen to represent groups of residential properties,

for example, and the assessor will need to consider the approximate number of people exposed to impacts

in the various different categories of severity, in order to reach a conclusion on the significance of effect.

An individual property exposed to a moderately adverse impact might not be considered a significant

effect, but many hundreds of properties exposed to a slight adverse impact could be. Such judgements

will need to be made taking into account multiple factors and this guidance avoids the use of prescriptive

approaches.

7.12 7.13 Replacement text: Where the air quality is such that an air quality objective at the building façade is not

met, the effect on residents or occupants will be judged as significant, unless provision is made to reduce

their exposure by some means.

6

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

1. Purpose and structure of this guidance

1.1 Environmental Protection UK (EPUK) and the Institute of Air

Quality Management (IAQM) have produced this guidance to

ensure that air quality is adequately considered in the land-use

planning and development control processes.

1.2

The spatial planning system has an important role to play in

improving air quality and reducing exposure to air pollution. Both

the development of local planning policies and the determination

of individual planning applications are important, the former

setting the framework for the latter. This guidance focuses

on development control, but also stresses the importance of

having good air quality policies within local authority planning

frameworks.

1.3 The intended audience for this guidance is made up of

air quality and planning officers within local authorities, and

developers and consultants involved in the preparation of

development proposals and planning applications.

1.4 This document has been developed for professionals operating

within the planning system. It provides them with a means of

reaching sound decisions, having regard to the air quality implications

of development proposals. It also is anticipated that developers

will be better able to understand what will make a proposal more

likely to succeed. This guidance, of itself, can have no formal or

legal status and is not intended to replace other guidance that does

have this status. For example, industrial development regulated by

the Environment Agency, and requiring an Environmental Permit, is

subject to the EA’s risk assessment methodology

1

, while for major

new road schemes, Highways England has prepared a series of

advice notes on assessing impacts and risk of non-compliance

with limit values

2

.

1.5

This guidance document is particularly applicable to assessing

the effect of changes in exposure of members of the public

resulting from residential and mixed-use developments, especially

those within urban areas where air quality is poorer. It will

also be relevant to any other forms of development where a

proposal could affect local air quality and for which no other

guidance exists. This guidance is not intended to be applied

to the assessment of air quality impacts on designated nature

conservation sites

3

.

1.6 The guidance sets out why air quality is an important

consideration in many aspects of local authority spatial planning.

It emphasises how good spatial planning can reduce exposure to air

pollution, as well as providing other benefits of well-being to the

wider community. It also emphasises the importance of applying

good design and ‘best-practice’

4

measures to all developments,

to reduce both pollutant emissions and human exposure. It also

provides guidance on how air quality considerations of individual

schemes may be considered within the development control

process, by suggesting a framework for the assessment of the

impacts of developments on local air quality.

1.7 Chapters 1 to 4 of this guidance set out the role of the planning

regime, the important links between air quality and human health,

and the links between planning and environmental assessment.

Chapters 5 to 8 then describe the roles of the local authority

and developer/applicant in the process through which air quality

and planning decisions are taken. More specifically, Chapter

5 deals with the overarching concepts of land-use planning

and air quality that should be applied throughout the strategic

planning and development control processes; it emphasises

that all developments should incorporate good principles of

design with regard to minimising emissions and the reduction

of impacts on local air quality. Chapters 6 to 8 then deal with

the assessment of individual planning applications; the approach

set out herein is founded on the concept that the principles

set out in Chapter 5 are firmly adhered to, but recognises that

within the development control process decisions have to be

made by local planning authorities on a case-by-case basis. A

flow chart describing the overall process through Chapters 5 to

8 is shown below in Figure 1.

1.8 This guidance is not intended to cover the specific assessment

of odour or construction dust effects that some developments

may give rise to. Separate guidance has been published by

IAQM i.e. ‘Guidance on the assessment of odour for planning’

and ‘Guidance on the assessment of dust from demolition and

construction’ and these guidance documents should be consulted

as appropriate

5

.

1.9

This guidance could be adapted for use in the Scottish and/

or Northern Ireland planning systems, because it is considered

that the general principles of air quality assessment set out herein

are applicable in all parts of the United Kingdom.

Figure 1: Procedure for Evaluating New Developments

EPUK & IAQM Land-Use Planning & Development Control: Planning For Air Quality 7

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

1. Review proposed development for evidence of

emission reduction and good design (See Chapter 5).

2. Screen where an air quality assessment

required (see Chapter 6)

3. Undertake an air quality assessment (See

Chapter 6).

4. Determine whether the air quality impact or

exposure is significant or not (see Chapter 7).

5. If significant identify additional mitigation

required.

6. Prepare air quality report.

2a. If not prepare short report/technical

note explaining the grounds for

screening out the need for an assessment.

1

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/air-emissions-risk-assessment-for-your-environmental-permit

2

www.standardsforhighways.co.uk/ians.

3

The IAQM and the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management are considering (as of Spring 2015) where such guidance would be useful

for professionals working in this area.

4

Best practice in this guidance implies those measures which are currently considered to be the best available – this does not preclude better practice in the future.

5

http://iaqm.co.uk/guidance.

8

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

2. The Role of the Planning Regime

2.1 Land-use planning can play a critical role in improving local

air quality. At the strategic level, spatial planning can provide for

more sustainable transport links between the home, workplace,

educational, retail and leisure facilities, and identify appropriate

locations for potentially polluting industrial development. For

an individual development proposal, there may be associated

emissions from transport or combustion processes providing

heat and power.

2.2 The pattern of land use determines the need for travel,

which is in turn a major influence on transport related emissions.

Decisions made on the allocation of land use will dictate future

emissions, as many people and businesses will make significant

use of road transport for journeys between places that form

part of their daily lives. Suppressing this demand for travel by

road can only be achieved by having a plan that recognises this

demand. Considering the merits of individual development

proposals in isolation is less likely to deliver a pattern of land

use that is more sustainable. Ideally, planning authorities should

have policies that reflect the desirability of reducing the demand

for road journeys with polluting vehicles. Local Transport Plans,

prepared in England by strategic transport authorities, contain

some of this thinking and are required to consider mechanisms

for reducing the need for travel.

2.3 Policies that promote high quality building standards,

reduce energy use, and require the preparation of low emissions

strategies, can help to reduce local emissions of air pollutants.

They will also align with other policies aimed at increasing

sustainability, notably for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

2.4 Development is not inherently negative for air quality. Whilst

a new development at a particular site may have its own emissions,

it may also bring an opportunity to reduce overall emissions in

an area over time by installing new, cleaner technologies and

applying policies that promote sustainability. The installation of

more efficient low NO

x

boilers is one obvious example.

2.5 The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) in England,

and Planning Policy Wales (PPW), set out the important role

of local authorities as contributing to the protection of and

enhancement of the environment. As part of this role they should

help to improve biodiversity, minimise waste and pollution, and

mitigate and adapt to climate change including moving to a low

carbon economy. It requires local authorities to grant planning

permission in conformity with NPPF/PPW and the local plan,

where there are no relevant policies or where these are out of

date, unless any adverse impacts of doing so would significantly

and demonstrably outweigh the benefits.

2.6 Specifically, planning policies should sustain compliance

with, and contribute towards, meeting EU limit values or national

objectives for air pollutants

6

, taking into account the presence

of Air Quality Management Areas (AQMAs) and the cumulative

impacts on air quality from individual sites in local areas. Planning

decisions should ensure that any new development in an Air

Quality Management Area is consistent with the local air quality

action plan.

2.7 Local authorities therefore need to set out their policies to

achieve good air quality, both within Air Quality Management

Areas and more widely across their districts and periodically to

review them to keep them relevant and up to date.

2.8 Many authorities have already done so and have included

these in their air quality action plans, supplementary planning

documents or within other documents.

6

The air quality objectives for England are defined in the Air Quality (England) Regulations 2000 and the Air Quality (England) (Amendment) Regulations 2002;

within Wales they are defined in the Air Quality (Wales) Regulations 2000 and the Air Quality (Wales) (Amendment) Regulations 2002. The EU Limit Values are

transposed into UK legislation within the Air Quality Standards Regulations 2010.

EPUK & IAQM Land-Use Planning & Development Control: Planning For Air Quality 9

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

3.1 Planning has an important influence on air quality and also,

therefore, the health of humans and ecosystems. Ideally, air

quality should be a prime consideration for long term planning,

so that land is used and allocated in ways that minimise emissions

and that reduce the exposure of people to air pollution. As

a minimum, the planning system should not take decisions

on individual proposals that lead to unacceptably poor air

quality, nor should it make a series of decisions that collectively

produces this undesirable outcome. The best means of ensuring

that this does not occur is to have sound policies in place that

guide decision making. This document explains what those

desirable policies might be to promote better air quality and

how individual proposals are best evaluated.

3.2

It is now beyond dispute that air quality is a major influence

on public health and so improving air quality will deliver real

benefits. In England, with the move of Directors of Public Health

into local authorities, along with the creation of Health and

Wellbeing Boards and Joint Strategic Needs Assessments, there

is another opportunity to refresh the collaboration between

professionals working in planning, transport, environmental

health and public health so that collective decisions can be

made that influence both air quality and health positively.

3.3 In the UK it has been estimated that the mortality burden

of long term exposure to particulate matter (PM

2.5

) in 2008 was

equivalent to nearly 29,000 premature deaths in those aged 30

or older

7

. The Public Health Outcomes Framework data tool

shows the fraction of mortality attributable to air pollution by

local authority (range 2.7 - 8.3%, average for England 5.4%)

8

. It is

likely that removing exposure to all PM

2.5

would have a bigger

impact on life expectancy in England and Wales than eliminating

passive smoking or road traffic accidents

9

. The economic cost

from the impacts of air pollution in the UK is estimated at £9-19

billion every year which is comparable to the economic cost

of obesity (over £10 billion)

10

. In 2013, the International Agency

for Research on Cancer has identified outdoor air pollution as

causing lung cancer, without identifying the specific pollutants

that are the carcinogenic component

11

.

3.4 Nitrogen dioxide can also, independently of particulate

matter, play an adverse role in exacerbating asthma, bronchial

symptoms (even in healthy individuals), lung inflammation and

reduced lung function. Reduced lung function growth is also

linked to nitrogen dioxide exposure at concentrations currently

found in many urban areas. There is also an increasing awareness of

evidence, as summarised in the HRAPIE review by the WHO

12

, that

chronic exposure to NO

2

may be important for premature mortality

effects. The strength of this evidence is less than it is for the much

3. Links between poor air quality, human

health and the environment

Image: © Roger Barrowcliffe

10

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

larger body of evidence for particles, with regard to the use of a

concentration-response function that is suitable for quantification

of the impact on mortality. The evidence is considered by the

Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants to be sufficient

to conclude that NO

2

is causing some of the health effects observed

in epidemiological studies

13

.

The Committee recommends that

concentration response functions for the association between NO

2

and premature mortality can be used, with some qualifications

14

.

When applied on a national basis, use of these functions suggests

that the national premature mortality burden for long term exposure

to NO

2

is equivalent to 23,000 deaths annually

15

.

3.5 Emissions of some airborne pollutants are known to damage

the health of ecosystems, often in subtle and long term ways.

Much more is now known about the effects of excess acidity

and nutrient nitrogen on plants, which have been taking place

over a long period of time. Many sensitive areas of the UK are

still adversely affected and are in an unfavourable condition,

despite the reduction in national emissions of SO

2

and NO

x

.

Agriculture is a dominant source of ammonia emissions which

contribute to acidity and nutrient nitrogen. Intensive livestock

units can be a significant local source of ammonia, for example.

As noted in the Introduction (paragraph 1.4) this guidance is not

designed to assess the impacts of air pollution on ecosystems.

3.6 The control of air pollution is the responsibility of local

authorities and other government agencies through several

Acts of Parliament and Regulations. Air pollution has many

sources and is not confined by administrative boundaries and

consequently its control requires regulatory authorities and

national government to use a wide range of policy levers to

influence air quality. Local authorities have a wide remit and their

responsibilities touch on many aspects of our lives. To achieve

their objectives they need to draw on many different resources,

some statutory, and some that rely on cooperation with others.

Good air quality is one such objective, where many players can

affect the outcome through actions taken in different places

and sometimes over long periods of time as one development

succeeds another. Determining one application in isolation may

not achieve good air quality on its own. This is often achieved

through many decisions made in different circumstances guided

by a mosaic of policies that implemented together will create

better air quality.

7

The Mortality Effects of Long-Term Exposure to Particulate Air Pollution in the United Kingdom. The Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants

(COMEAP) (2010) www.gov.uk/government/publications/comeap-mortality-effects-of-long-term-exposure-to-particulate-air-pollution-in-the-uk

8

Public Health England. (2013). Health Protection. Available: www.phoutcomes.info/public-health-outcomes-framework#gid/1000043/pat/6/ati/101/page/8/

par/E12000002/are/E06000008. (Accessed 20/1/14).

9

Comparing estimated risks for air pollution with risks for other health effects, Miller and Hurley, IOM (2006) www.iom-world.org/pubs/IOM_TM0601.pdf.

10

www.defra.gov.uk/environment/quality/air/air-quality/impacts/ 11 IARC Scientific Publication No. 161 Air Pollution and Cancer, Editors: K. Straif, A. Cohen,

and J. Samet, 2013, Lyon

12

www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/238956/Health-risks-of-air-pollution-in-Europe-HRAPIE-project,-Recommendations-for-concentration-

response-functions-for-costbenefit-analysis-of-particulate-matter,-ozone-and-nitrogen-dioxide.pdf.

13

COMEAP (2015) Statement on the Evidence for the Effects of Nitrogen Dioxide on Health, 12 March 2015 (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/

nitrogen-dioxide-health-effects-of-exposure).

14

www.gov.uk/government/publications/nitrogen-dioxide-interim-view-on-long-term-average-concentrations-and-mortality

15

www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/486636/aq-plan-2015-overview-document.pdf

EPUK & IAQM Land-Use Planning & Development Control: Planning For Air Quality 11

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

Policy context

4.1 This Chapter provides a brief overview of the important

aspects of land use planning in the context of this Guidance. A

more detailed review of the land use planning system in the UK

is provided in Essential Environment

16

, a regularly updated online

and hardcopy service provided by Environmental Protection

UK. Information may also be obtained from the Government’s

various specialist websites (e.g. www.laqm.defra.gov.uk).

4.2 The 2008 Planning Act

17

introduced a change in the planning

consent regime for major or ‘nationally significant’ infrastructure

projects, for example energy, transport, water and waste. The

Localism Act 2011 makes a number of amendments to the Planning

Act concerning consent for infrastructure planning which is now

the responsibility of the Major Infrastructure Planning Unit.

4.3 Local authorities at district, county and unitary level retain

the responsibility for decisions on all other developments except

where the Secretary of State determines those applications

subject to Appeal. In arriving at a decision about a specific

proposed development the local planning authority is required to

achieve a balance between economic, social and environmental

considerations. For this reason, appropriate consideration of

issues such as air quality, noise and visual amenity is necessary.

In terms of air quality, particular attention should be paid to:

• compliance with national air quality objectives and of EU

Limit Values

18

,

19

;

•

whether the development will materially affect any air

quality action plan or strategy;

•

the overall degradation (or improvement) in local air quality; or

•

whether the development will introduce new public

exposure into an area of existing poor air quality.

4.4

The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and the

Planning Policy Wales (PPW) set out planning policy for England

and Wales respectively. They place a general presumption in

favour of sustainable development, stressing the importance

of local development plans, and state that the planning system

should perform an environmental role to minimise pollution.

One of the NPPF twelve core planning principles notes that

planning should “contribute to…reducing pollution”, whilst PPW

includes a core principle that requires respect for environmental

limits such that resources are not irrecoverably depleted or the

environment irreversibly damaged. Both NPPF and PPW recognise

that to prevent unacceptable risks from air pollution, planning

decisions should ensure that new development is appropriate

for its location. The policies state that the effects of pollution

on health and the sensitivity of the area and the development

should be taken into account.

4.5 The NPPF/PPW states that: “Planning policies should sustain

compliance with and contribute towards EU limit values or national

objectives for pollutants, taking into account the presence of Air

Quality Management Areas and the cumulative impacts on air

quality from individual sites in local areas. Planning decisions should

ensure that any new development in Air Quality Management Areas

is consistent with the local air quality action plan”.

4.6 The NPPF is supported by Planning Practice Guidance (PPG),

whilst PPW is supported by Technical Advice Notes (TANs) and

Supplementary Planning Guidance. These include guiding principles on

how planning can take account of the impacts of new development

on air quality. The PPG states that “Defra carries out an annual

national assessment of air quality using modelling and monitoring

to determine compliance with EU Limit Values” and “It is important

that the potential impact of new development on air quality is taken

into account … where the national assessment indicates that relevant

limits have been exceeded or are near the limit”. The role of the local

authorities is covered by the LAQM regime, with the guidance stating

that local authority Air Quality Action Plans “identify measures that

will be introduced in pursuit of the objectives”. The PPG makes clear

that “Air quality can also affect biodiversity and may therefore impact

on our international obligation under the Habitats Directive”, and

in addition, that “Odour and dust can also be a planning concern,

for example, because of the effect on local amenity”. In Wales, a

specific link has been made between air quality and noise such that

where Air Quality Action Plans prioritise measures in terms of costs

and benefits, traffic noise

20

should also be given due consideration,

qualitatively if not quantitatively.

4.7 The PPG states that “Whether or not air quality is relevant

to a planning decision will depend on the proposed development

and its location. Concerns could arise if the development is likely

to generate air quality impact in an area where air quality is

known to be poor. They could also arise where the development

is likely to adversely impact upon the implementation of air

quality strategies and action plans and/or, in particular, lead to

a breach of EU legislation (including that applicable to wildlife)”.

4.8 The PPG sets out the information that may be required in an

air quality assessment, making clear that “Assessments should be

proportional to the nature and scale of development proposed

and the level of concern about air quality”. It also provides

examples of the types of measures to be considered. It states that

“Mitigation options where necessary, will depend on the proposed

development and should be proportionate to the likely impact”.

4. Planning Framework

12

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

4.9 An overview of the context of air quality and planning at a

national, regional and local level is set out in Table 4.1. The air

quality impacts of a planning application will be judged against

the policies within these documents.

Supplementary Planning Documents and Guidance

4.10 Supplementary Planning Documents/Guidance (SPDs or

SPGs) represent guidance formally adopted by local authorities in

England. They provide additional information in relation to specific

policy areas within the Local Development Framework. Many local

authorities have now published SPGs or SPDs on air quality

21

. Often

these draw on information provided in previous versions of this

guidance. They generally set out when an air quality assessment is

required and what it should include. Some also include criteria for

assessing the significance of the impact of a proposed development.

These documents are a very useful tool for providing transparent

and consistent advice to both Development Control departments

and developers. They can also provide a means for assessing the

adequacy of an air quality assessment.

4.11 SPGs and SPDscan be taken into account when considering

planning applications, and weight accorded to them will be

increased ifthey havebeen subject to public consultation.

Appropriate air quality policies should, however, underpin the more

detailed guidance in the SPD or SPG to ensure its effectiveness.

The Planning Process

4.12 Development proposals may be submitted as outline or full

applications. Outline applications should contain sufficient detail

to allow the impacts to be properly assessed. Pre-application

discussions between developers, or their representatives, and

local authorities are encouraged to ensure an application is

complete and meets the necessary requirements. The decisions

made by local authorities should be made in accordance with the

local policies and plans, unless there are material considerations

to suggest otherwise.

4.13 The applicant may receive an unconditional permission

or, more likely, for those developments requiring an air quality

assessment, permission subject to conditions. The application

can also be refused. Outline applications may be approved

subject to reserved matters. In some circumstances conditions

or the reserved matters require an air quality assessment prior

to commencement of site works or occupation/use of a

development. This is not good practice as it is unlikely that

major changes will take place to mitigate any impacts at this

late stage in the design of a new development.

4.14 Air quality (and other) impacts can be controlled through

the application of planning conditions or through planning

obligations (often known as ‘section 106 agreements’)

22

.

Conditions are specific to the development, while planning

obligations can have a wider remit. For instance, a planning

condition might be used to require the installation of a

suitable ventilation system, while an obligation often requires

a financial contribution, for example, to require a “car club”

to be set up. Conditions and planning obligations have

different legal standing and advice from planners should be

sought to determine the appropriate approach to apply to

mitigate the air quality impacts of specific developments.

Combinations of planning conditions and obligations are

now often used to fund Low Emission Strategies. The

Community Infrastructure Levy is a more recently introduced

mechanism that requires developers to contribute to new

local infrastructure, which may be relevant to improving air

quality in some cases.

Material Considerations

4.15 The planning system recognises that, in principle, any

consideration which relates to the use and development of land

is capable of being a planning consideration. This includes air

quality. The circumstances of a particular planning application will

determine whether or not this is the case in practice. Material

considerations must be genuine planning considerations, relating

specifically to the development and use of land in the public

interest. They must also fairly and reasonably relate to the

application concerned.

4.16 Where a planning application runs counter to relevant

local policies, it is not normally permitted, unless other material

planning considerations outweigh the objections and justify

granting permission. This emphasises the importance of ensuring

that appropriate planning policies dealing with air quality are

Level Relevant Documentation

National National Planning Policy Framework

Planning Practice Guidance

Air Quality Strategy 2007

Regional

Regional Air Quality Strategy

a

Local Local Development Framework (LDF)

Supplementary Planning Documents (SPD)

Air Quality Action Plans

Local Air Quality Guidance

Neighbourhood Plans

a

For example the Mayor’s Air Quality Strategy in London

Table 4.1: Context of air quality and planning in England.

EPUK & IAQM Land-Use Planning & Development Control: Planning For Air Quality 13

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

in place. Particular attention is paid to whether such policies

are met or not during the planning appeals process. If effective

policies for air quality management are in place, either within

the LDF/P, Local Plan, or a SPD, then air quality issues can be

accounted for in decision making far more than in cases where

there are only weak or no relevant policies.

Air quality as a material consideration

4.17 Any air quality issue that relates to land use and its

development is capable of being a material planning consideration.

The weight, however, given to air quality in making a planning

application decision, in addition to the policies in the local plan,

will depend on such factors as:

• the severity of the impacts on air quality;

•

the air quality in the area surrounding the proposed development;

•

the likely use of the development, i.e. the length of time

people are likely to be exposed at that location; and

•

the positive benefits provided through other material considerations.

4.18

Chapter 7 of this Guidance explores in more detail how to

judge the significance of the air quality impacts of a development

proposal, and inform the outcome in terms of planning decisions.

4.19 Some air quality assessments will be undertaken for

development that falls within the scope of the Environmental

Impact Assessment Regulations

23

. Such assessments will need to

recognise the requirements of these Regulations, in respect of the

need to define likely significant effects and identify mitigation, for

example. This guidance has been written to take into account

the EIA regulations, although it is not written purely for their

requirements. It is also possible that the Habitats Regulations

would invoke the need for an air quality assessment, should the

development have potential for affecting a designated site of

nature conservation at the European level, i.e. a Special Area of

Conservation (SAC), a Special Protection Area (SPA) or a Ramsar

site. Such an assessment is not part of this guidance, however.

Linkages with other relevant issues

4.20 Decision-makers need to take account of a wide range of

potential impacts arising from new developments. In many cases

there are linkages between air quality and these other issues.

Examples include the use of road humps to limit traffic speeds

and improve safety, which can in turn increase emissions through

vehicles braking and then accelerating and the use of biomass

boilers to reduce climate change impacts, which can increase

emissions of particulate matter and NO

x

. It is important that

these linkages are fully understood and taken into account to

optimise the opportunities to enhance the sustainability of new

developments. This may require the input of other specialists.

16

See www.pollutioncontrolonline.org.uk or http://www.essentialenvironment.org.uk

17

www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2008/ukpga_20080029_en_1.

18

The duty to meet EU Limit Values is placed on the Secretary of State and not local government.

19

The precise role of the development control process in delivering compliance with the EU limit values is uncertain, and clarification has been sought from Defra.

20

Local Air Quality Management Policy Guidance for Wales, Addendum Air Quality and Traffic Noise (2012).

21

Example in Annexe 3: www.lowemissionstrategies.org/downloads/LES_Good_Practice_Guide_2010.pdf

22

See www.communities.gov.uk/publications/planningandbuilding/circularplanningobligations.

23

The Town and Country Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2011 SI no. 1824.

14

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

Introduction

5.1 This section explains how all development proposals

can adopt good design principles that reduce emissions and

contribute to better air quality management. The roles of

the local authority and developer/applicant in the process

by which air quality and planning decisions are taken are

set out and commentary is given on how both the strategic

planning and development control processes can contribute

to good practice for all new development. The flow chart in

Figure 2 below provides an overview of the whole process,

defining the roles of the various parties and identifying

opportunities for optimising the development proposal so as

to reduce emissions. The concepts outlined in this section are

applicable to all development and can be applied regardless

of the outcome of any air quality assessment, as described

in Section 6.

Overarching Concepts in Land Use Planning for

Better Air Quality

5.2

The land-use planning and development control system

has an important role to play in driving forwards improvements

in local air quality, minimising exposure to pollution, and to

improving the health and well-being of the population.

5.3 Whilst land-use planning and development controls rarely

provide immediate solutions to improving air quality, they can

ensure that future problems are prevented or minimised.

5.4 This guidance deals primarily with the development control

process that is applied to determining individual applications.

The role of planning at the strategic level must not be

understated, however. Effective spatial planning can reduce the

need to travel by car to the workplace, schools, shopping and

leisure facilities by ensuring new dwellings are located in areas

where such facilities are readily available, or where alternative

transport modes are avaialble. Careful consideration to building

design and layout can assist in minimising exposure to future

occupants. Policies that enforce high building standards can

play an important role in reducing emissions from services

that provide heating and hot water – an increasingly important

sector as measures to tackle transport emissions are tightened.

Making Better Use of the Land-use Planning System

5.5 The land-use planning system has significant potential to influence

local air quality positively through the careful design of neighbourhoods.

Some actions which are strongly encouraged include:

•

Full integration of the inputs of the planning, transport, housing,

education and environment departments to ensure that environmental

considerations, including those related to air quality, are considered at

the earliest stages of the strategic planning processes;

• Ensuring public services are joined up and easier to access via public

transport or other sustainable choices such as cycling and walking; and

•

Giving careful consideration to the location of developments

(e.g. within the development of Site Allocation Policies)

5. Better by design

Image: © Debu55y | Fotolia.com

EPUK & IAQM Land-Use Planning & Development Control: Planning For Air Quality 15

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

a

Major applications are usually determined by the Development Control Committee; but in some cases the decision may be delegated to Planning Officers.

b

Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended).

c

Community infrastructure levy.

Local Planning Authority (LPA)

Pre-application discussions

Enforcement of planning requirements

Prepares AQA and issues to LPA, may provide clarification or

further information in response to comments

Consults on whether an air quality assessment (AQA) is required

Consults on the AQA methodology

Input to draft planning conditions

May provide clarification or further information in response to

comments

Input to S106/CIL

Applicant makes short representation in person

Developer submission(s) to show pre-development conditions

complied with

Consults on assessments required

Strategic Planning

Air Quality Policy(ies) in Core Document. Supplementary

Planning Document (SPD), good practice guidance,

and / or Air Quality Action Plan (AQAP) sets out local

assessment requirements, best practice/minimum

standards and financial contributions

Development Control

Determines whether an AQA is required. Informs applicant

/developer of air quality policies in plan/SPD/AQAP or

other document, and requirements for best practice for

all developments

Air Quality Officer comments

Air Quality Officer provides planning department

with comments on application including their

recommendations

Statutory bodies consulted, and comments submitted to

planning officer

Planning conditions drafted e.g. on mitigation measures

S106

b

or CIL

c

agreement e.g. contribution to mitigation or

Low Emission Strategy

Planning Officer prepares report with recommendations

for the Development Control (DC) Committee

a

DC Committee makes decision

a

. May refer matter back to

Planning Department for more information; may require

additional conditions

Agree pre-development planning conditions have been

complied with. Possibly request further information

Developer may make representations during public

consultation

Applicant / Developer

Figure 2: Role of Local Authority and Applicant/Developer in the planning process

16

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

BOX 1: Examples of Approaches to Reducing Emissions

and Impacts

1. Air Quality and emissions mitigation guidance for

Sussex authorities

The Sussex Air Quality Partnership has prepared guidance

to assess the potential impacts of new development,

providing a consistent approach to mitigation. The

guidance follows a three stage process. The first stage

is used to screen out developments that will have very

small impacts, on the basis of their size or location. All

developments that are not screened out are required

to carry out an “emissions mitigation assessment”. This

quantifies the additional emissions generated by traffic for

the development (following a set of defined assumptions)

and then assigns a monetary value to this (over a 5 year

period, based on Defra’s damage cost approach). This

defines the value of mitigation that should be applied,

preferably on-site.

For some developments, e.g. those within an AQMA,

developments that exceed threshold criteria for parking or

traffic generation, or where new exposure is introduced, an

air quality assessment is also required, to determine the likely

significant effects.

2. West Yorkshire Air Quality and Emissions Planning

Guidance

The West Yorkshire Low Emissions Strategy Group

has published guidance for integrating air quality

considerations into land-use planning and development

management policies. The air quality assessment

process follows three stages:

Determining the classification of the development

proposal – schemes are classified as Minor, Medium or

Major based on criteria that would trigger the need for

a Transport Assessment (Medium) and those that meet

additional criteria such as lying within an AQMA, exceeding

thresholds for traffic generation etc. (Major).

Air quality impact assessment – Minor and Medium

development proposals are further screened to identify

if they will introduce new exposure, which subsequently

influences the degree of mitigation required. Major

development proposals are required to complete both a

detailed air quality assessment (to determine likely significant

effects) and a quantification of pollutant emission costs

(for traffic generation only) based on a set of defined

assumptions and using Defra’s damage cost approach.

Mitigation and compensation - the outcome of stage 2

is used to determine the level of appropriate mitigation.

Default mitigation measures are proposed for Minor, Medium

and Major development; for the latter the scale of mitigation

is related to the calculated pollution damage costs.

3. Greater London Authority – Air Quality Neutral Policy

The Mayor’s SPG on Sustainable Design and Construction

requires ultra-low NO

x

boilers in all new developments and

sets emissions standards for all new CHP and biomass plant.

The SPG also sets out guidance on the implementation of “air

quality neutral” in London. This is achieved by establishing

benchmarks for both building and transport emissions which

all new developments must comply with. Where compliance

cannot be achieved, developers are required to prepare strategies

to demonstrate how the excess will be mitigated, on or off-site.

where particularly sensitive members of the population are

likely to be present e.g. school buildings should generally be

sited 100m or more away from busy roads, in areas where

pollution concentrations are high.

Examples of Approaches to Reducing Emissions

and Impacts

5.6 A particular concern of many local authorities is that

individual developments are often shown to have a very small air

quality impact, and, as a consequence, there are few mechanisms

available to the planning officer to require the developer to

achieve lower emissions. This, in turn, leads to concerns about

the potential air quality impacts of cumulative developments as

many individual schemes, deemed insignificant in themselves,

contribute to a “creeping baseline”.

5.7 To tackle this issue, a number of authorities have developed

various approaches to identify the requirement for good practice

and design requirements at an early stage of the assessment

process. A summary of a number of these approaches is set

out in Box 1; in the majority of cases, these approaches only

consider emissions from road traffic generated by the scheme.

The basic concept is that good practice to reduce emissions and

exposure is incorporated into all developments at the outset,

at a scale commensurate with the emissions.

5.8 It is probably not practicable or appropriate to apply the

approaches described in Box 1 to very small developments which

will have only a very small impact on local air quality conditions.

An approach that is commonly used is to consider only “major”

developments, such as defined within the Town and Country

Planning (Development Management Procedure) Order (England)

2010 [(Wales) 2012]. These include developments where:

• The number of dwellings is 10 or above;

•

The residential development is carried out on a site of more

than 0.5ha where the number of dwellings is unknown;

•

The provision of more than 1000 m

2

commercial floorspace; or

• Development carried out on land of 1ha or more.

5.9 Developments which introduce new exposure into an area of

EPUK & IAQM Land-Use Planning & Development Control: Planning For Air Quality 17

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

existing poor air quality (e.g. an AQMA) should also be considered

in this context.

5.10 Principles of Good Practice

Good practice principles should be applied to all

developments that have not been screened out using

criteria such as those in paragraph 5.8. These cover both

emissions and exposure, and address both the design and

operational phases. Some examples of such principles

include the following.

Design phase

•

New developments should not contravene the Council’s

Air Quality Action Plan, or render any of the measures

unworkable;

•

Wherever possible, new developments should not create a

new “street canyon”, or a building configuration that inhibits

effective pollution dispersion;

•

Delivering sustainable development should be the key theme

of any application;

• New development should be designed to minimise public

exposure to pollution sources, e.g. by locating habitable

rooms away from busy roads, or directing combustion

generated pollutants through well sited vents or chimney stacks.

Operational phase

•

The provision of at least 1 Electric Vehicle (EV) “fast

charge” point per 10 residential dwellings and/or 1000m

2

of commercial floorspace. Where on-site parking is provided

for residential dwellings, EV charging points for each parking

space should be made.

• Where development generates significant additional

traffic, provision of a detailed travel plan (with

provision to measure its implementation and effect)

which sets out measures to encourage sustainable

means of transport (public, cycling and walking) via

subsidised or free-ticketing, improved links to bus

stops, improved infrastructure and layouts to improve

accessibility and safety.

•

All gas-fired boilers to meet a minimum standard of <40

mgNO

x

/kWh.

•

All gas-fired CHP plant to meet a minimum emissions standard of:

˚ Spark ignition engine

22

:

250 mgNO

x

/Nm

3

;

˚ Compression ignition engine

23

: 400 mgNO

x

/Nm

3

;

˚ Gas turbine

24

: 50 mgNO

x

/Nm

3

.

•

A presumption should be to use natural gas-fired installations.

Where biomass is proposed within an urban area it is to meet

minimum emissions standards of:

˚

Solid biomass boiler

25

: 275 mgNO

x

/Nm

3

and 25 mgPM/Nm

3

.

(These suggested emission benchmarks represent readily

achievable emission concentrations by using relatively simple

technologies. They can be bettered by using more advanced

control technology and at additional cost over and above the

‘typical’ installation.).

Image: © Mark6138 | Dreamstime.com

18

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

22

At reference conditions of 273K, 101.3 kPa, 5%O

2

and 0% H

2

O.

23

At reference conditions of 273K, 101.3kPa, 5%O

2

and 0% H

2

O.

24

At reference conditions of 273K, 101.3 kPa, 15% O

2

and 0% H

2

O.

25

At reference conditions of 273K, 101.3 kPa, 6%O

2

and 0% O

2

26

Dickens R, Gill J, Rubin and Butterwick M (2013) Valuing impacts on air quality: Supplementary Green Book guidance. HM Treasury and Defra.

27

www.gov.uk/air-quality-economic-analysis#damage-costs-approach.

Offsetting Emissions

5.11 In addition to these good practice principles, local

authorities may wish to incorporate additional measures

to offset emissions at an early stage. It is important that

obligations to include offsetting are proportional to the

nature and scale of development proposed and the level

of concern about air quality; such offsetting can be based

on a quantification of the emissions associated with the

development. These emissions can be assigned a value, based

on the “damage cost approach” used by Defra, and then

applied as an indicator of the level of offsetting required,

or as a financial obligation on the developer. Unless some

form of benchmarking is applied, it is impractical to include

building emissions in this approach, but if the boiler and CHP

emissions are consistent with the standards as described

above then this is not essential.

5.12 An approach that has been widely used to quantify the

costs associated with pollutant emissions from transport is to:

•

Identify the additional trip rates (as trips/annum) generated

by the proposed development (this information will normally

be provided in the Transport Assessment to;

• Assume an average distance travelled of 10km/trip;

•

Calculate the additional emissions of NO

x

and PM

10

(kg/

annum), based on emissions factors in the Emissions Factor

Toolkit, and an assumption of an average speed of 50 km/h;

•

Multiply the calculated emissions by 5, to assume emissions

over a 5 year time frame;

•

Use the HM Treasury and Defra IGCB damage cost approach

26

to provide a valuation of the excess emissions, using the

currently applicable values for each pollutant

27

; and

• Sum the NO

x

and PM

10

costs.

5.13 The cost calculated by these means provides a possible

basis for defining the financial commitment required for the

offsetting emission reductions or the contribution provided

by the developers as ‘planning gain’.

5.14 Typical measures that may be considered to offset

emissions include:

• Support for and promotion of car clubs;

•

Contributions to low emission vehicle refuelling infrastructure;

•

Provision of incentives for the uptake of low emission vehicles;

•

Financial support to low emission public transport options; and

• Improvements to cycling and walking infrastructure.

5.15 Measures to offset emissions may also be applied as post

assessment mitigation.

Image: Roger Barrowcliffe

6. Undertaking an Air Quality Assessment

EPUK & IAQM Land-Use Planning & Development Control: Planning For Air Quality 19

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

Purpose

6.1 The air quality assessment is undertaken to inform the

decision making with regard to the development. It does not,

of itself, provide a reason for granting or refusing planning

permission. Almost all development will be associated with new

emissions if the development is considered in isolation. In most

cases, therefore, development will be associated with adverse

impacts. These impacts require quantification and evaluation

in the context of air quality objectives and existing air quality.

The significance of the effects arising from the impacts on

air quality will depend on a number of factors and will need

to be considered alongside the benefits of the development

in question. Development under current planning policy is

required to be sustainable and the definition of this includes

social and economic dimensions, as well as environmental.

Development brings opportunities for reducing emissions at a

wider level through the use of more efficient technologies and

better designed buildings, which could well displace emissions

elsewhere, even if they increase at the development site.

Conversely, development can also have adverse consequences for

air quality at a wider level through its effects on trip generation.

6.2 Where a development requires an air quality assessment,

this should be undertaken using an approach that is robust and

appropriate to the scale of the likely impacts. One key principle

is that the assessment should be transparent and thus, where

reasonable, all input data used, assumptions made, and the

methods applied should be detailed in the report (or appendices).

6.3 As set out in the introduction in Chapter 1, this guidance

document is not intended to replace guidance that exists for

certain types of development, notably:

• industrial developments that require a Permit;

• highways schemes promoted by Highways England; or

•

activities associated with sources of dust (e.g. mineral

extraction, waste handling, construction) or odours.

Separate guidance is available for these sources. Clearly, where

new developments are located in the vicinity of such sources,

the potential impacts of their operation on the proposed

development will need to be considered.

6.4 The guidance provided by the Environment Agency and

Highways England has a formal status, reflecting the connections

these organisations have with Government departments. This

EPUK/IAQM guidance has no such status and is not intended

as a substitute for the formal guidance.

6.5 The matter of industrial development and its regulation by

the Environment Agency, Natural Resources Wales or a local

authority deserves some further consideration in a planning

context. The guidance provided by the Environment Agency

28

for

use in assessing emissions to air is intended (in part) to assist in

the determination of Best Available Techniques for an installation

regulated under the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED). This

EPUK/IAQM guidance document has been written so as to be

complementary to the EA guidance and not a substitute for it.

The EA’s risk assessment methodology has not been designed for

conducting an assessment to accompany a planning application,

especially one undertaken for the EIA Regulations. In these

circumstances, a framework is required that allows the assessor

to describe the degree of impacts before reaching a conclusion

on significance of the effects. The EA methodology does provide

some useful elements of such a framework, however, and, where

relevant, these have been used in this guidance, partly for reasons

of consistency. It must be recognised, however, that the EA

assessment methodology and the assessment guidance in this

document serve different purposes. The EA methodology is

intended for the purpose of screening out insignificant emissions

of individual pollutants and identifying where there is a risk of

of other pollutants emitted being potentially significant in terms

of environmental effects. This excercise is carried out as part

of the impact assessment in support of an application under

the Environmental Permitting Regulations. The IAQM/EPUK

guidance is intended to provide a means of reaching a conclusion

on whether the proposed development has a likely significant

effect on local air quality, taking into account the overall severity

of the impacts and other factors as appropriate. In each case,

the concept of significance has a deliberately different meaning

and context.

This document is not intended to address impacts on nature

conservation sites, for which a different form of assessment

is required.

The need for an air quality assessment

6.6 It is established good practice to consult with the Local Planning

Authority (and/or its air quality specialists) to gain agreement on the

need for an air quality assessment in support of a planning application

and if one is required, the approach and methodology that will be

used. The Planning Practice Guidance at paragraph 6 makes this point.

There is however a prior step in the consultation process, which is

to determine the very need for an assessment. If an assessment is

required, the approach and methodology can then be constructed

to deal with the key issues driving the need for the assessment.

6.7 To inform the consultation process, it will be important to

identify the locations of any AQMAs relative to the proposed

20

EPUK & IAQM u GUIDANCE

Planning For Air Quality

development, the main existing and proposed sources of

atmospheric pollution and the location of existing and proposed

human-health sensitive receptors.

6.8It is reasonable to expect that an assessment will be required

where there is the risk of a significant air quality effect, either from a

new development causing an air quality impact or creating exposure to

high concentrations of pollutants for new residents. To a large extent,

professional judgement will be required to determine whether an

air quality assessment is necessary as it is not possible to apply an

exact and precise set of threshold criteria to cover the wide variety

of development proposals. The following tables provide criteria that

may be useful to guide the consultation process in establishing the

need for an assessment. They separately consider:

•

the impacts of existing sources in the local area on the

development; and

• the impacts of the development on the local area.

6.9 Where an air quality assessment is identified as being

required, this may be either a Simple or a Detailed Assessment.

A Simple Assessment is one relying on already published

information and without quantification of impacts, in contrast

to a Detailed Assessment that is completed with the aid of a

predictive technique, such as a dispersion model. Much of the

discussion in this Section relates to Detailed Assessments. The

use of a Simple Assessment may be appropriate, where it will

clearly suffice for the purposes of reaching a conclusion on the

significance of effects on local air quality. A Simple Assessment

will be appropriate, if it can provide this evidence. Similarly, it

may be possible to conduct a quantitative assessment that does

not require the use of a dispersion model run on a computer.

6.10 The criteria provided are precautionary and should be

treated as indicative. They are intended to function as a sensitive

‘trigger’ for initiating an assessment in cases where there is a

possibility of significant effects arising on local air quality. This

possibility will, self-evidently, not be realised in many cases.

The criteria should not be applied rigidly; in some instances, it

may be appropriate to amend them on the basis of professional

judgement, bearing in mind that the objective is to identify

situations where there is a possibility of a significant effect on

local air quality.

6.11 In certain circumstances, it may be necessary to consider

whether the site itself is suitable for the introduction of new

emission sources. This could be because the neighbouring land

use has particular sensitivities to increased exposure to air

pollutants. It is not possible, or desirable, to set criteria that

would define such circumstances. In practice, it is more likely

that an assessment would reach a conclusion taking any local

factors into account.

Impacts of the Local Area on the Development

6.12 There may be a requirement to carry out an air

quality assessment for the impacts of the local area’s

emissions on the proposed development itself, to assess

the exposure that residents or users might experience.

This will need to be a matter of judgement and should

take into account:

•

the background and future baseline air quality and whether

this will be likely to approach or exceed the values set by

air quality objectives;

•

the presence and location of Air Quality Management

Areas as an indicator of local hotspots where the air quality

objectives may be exceeded;

Table 6.1: Stage 1 Criteria

•

the presence of a heavily trafficked road, with emissions

that could give rise to sufficiently high concentrations of

pollutants (in particular NO

2

), that would cause unacceptably

high exposure for users of the new development; and

• the presence of a source of odour and/or dust that may

affect amenity for future occupants of the development.

Criteria to Proceed to Stage 2

A. If any of the following apply:

• 10 or more residential units or a site area of more than

0.5ha

• more than 1,000 m

2