Walden University

ScholarWorks

Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Collection

2015

e Relationship Between Customer Relationship

Management Usage, Customer Satisfaction, and

Revenue

Robert Lee Simmons

Walden University

Follow this and additional works at: h*ps://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations

Part of the Business Commons

)is Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been

accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please

contact ScholarW[email protected].

Walden University

College of Management and Technology

This is to certify that the doctoral study by

Robert Simmons

has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects,

and that any and all revisions required by

the review committee have been made.

Review Committee

Dr. Ronald McFarland, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty

Dr. Alexandre Lazo, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty

Dr. William Stokes, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty

Chief Academic Officer

Eric Riedel, Ph.D.

Walden University

2015

Abstract

The Relationship Between Customer Relationship Management Usage, Customer

Satisfaction, and Revenue

by

Robert L. Simmons

MS, California National University, 2010

BS, Excelsior College, 2003

Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Business Administration

Walden University

September 2015

Abstract

Given that analysts expect companies to invest $22 billion in Customer Relationship

Management (CRM) systems by 2017, it is critical that leaders understand the impact of

CRM on their bottom line. The purpose of this correlational study was to investigate

potential relationships between the independent variables of customer satisfaction and

CRM utilization on the dependent variable of business revenue. The service-profit chain

formed the theoretical framework for this study. The study population included 203

service branches for an industrial equipment manufacturer in North America. The service

director for the subject organization provided the data for the study via data extracts from

the company’s corporate database. Some branches were eliminated, leaving a total

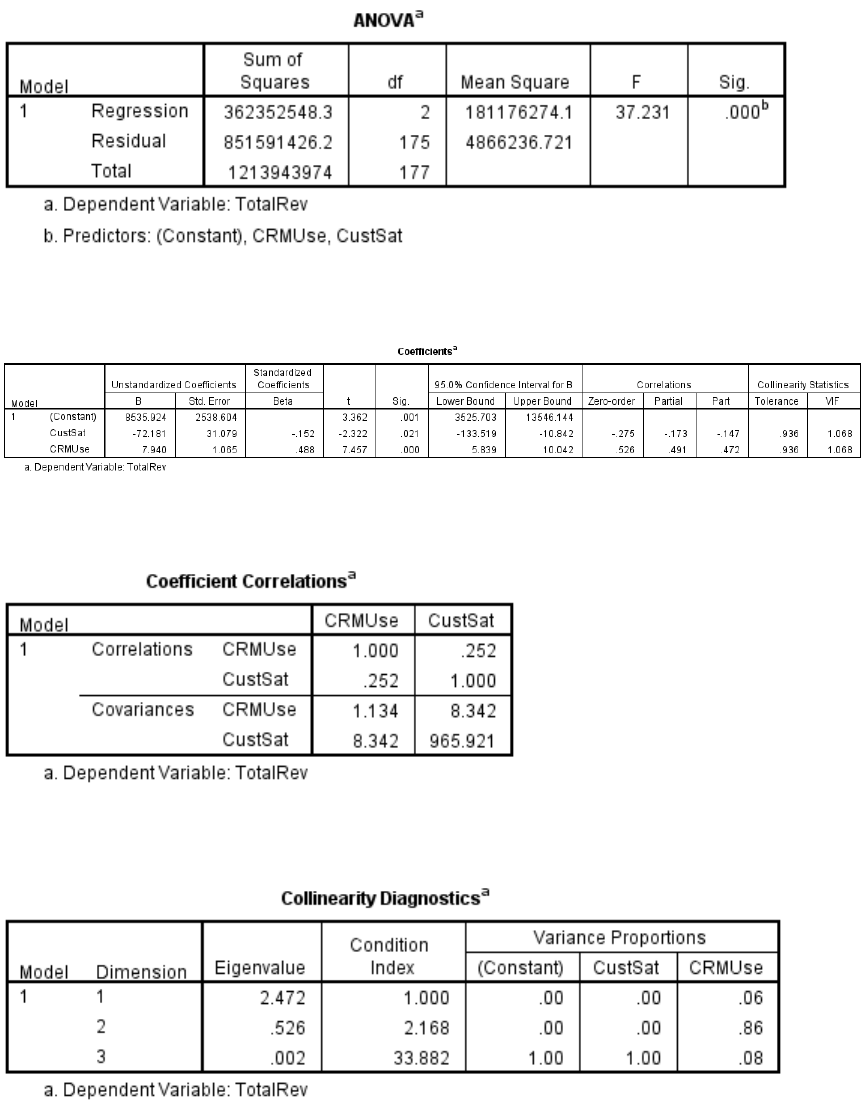

sample size of 178. The results of a multiple linear regression analysis showed that the

proposed model could significantly predict branch revenue F (2,175) = 37.321, p < .001,

R

2

= .298. Both CRM use and customer satisfaction were statistically significant, with

CRM use (beta = .488, p < .001) showing a higher contribution than customer

satisfaction (beta = -.152, p = .021). This study provides evidence to business executives

that CRM use has a strong positive influence on revenue. Additionally, this study

supports the findings of other studies that show a point of diminishing returns in

improved customer satisfaction. This study contributes to positive social change by

allowing firms to make better decisions with their investment dollars and by increasing

CRM utilization through cause-related marketing.

The Relationship Between Customer Relationship Management Usage, Customer

Satisfaction, and Revenue

by

Robert L. Simmons

MS, California National University, 2010

BS, Excelsior College, 2003

Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Business Administration

Walden University

September 2015

Dedication

The completion of this DBA doctoral study is the culmination of a life of

learning, perseverance, and determination. I wish that I could take credit for all of this but

that would be false. Primarily, I would never have made it through this journey without

the strength, guidance, and mercy of my Lord. In addition to all he has done for me, he

has blessed me with a wonderful family who has worked hard to make it possible for me

to reach this goal.

I am dedicating this dissertation to my amazing wife of 32 years, Karen. Without

her love and support, I would never make it out of bed in the morning. This

accomplishment is more a testament to her love, devotion, and belief in me than anything

I could have done on my own. When I was ready to give up, she pushed me forward.

When I thought I could no longer go on, she helped me through. She is due any honor,

title, or prestige that may come from this achievement.

Acknowledgments

Many people deserve my thanks for helping me achieve this goal. First, I would

like to thank my committee chair Dr. Ronald McFarland. Dr. McFarland has provided

countless hours of honest and needed feedback to help me along this journey. He has

worked diligently to help me get through this process as smoothly as possible. I would

also like to thank my other committee members Dr. Alexandre Lazo and Dr. William

Stokes. Both Dr. Lazo and Dr. Stokes have provided valuable feedback that helped me

improve the quality of my work and ensured my study lived up to the rigid academic

standards of Walden University.

I would also like to thank Dr. Freda Turner and all of the DBA program faculty

and staff. I cannot forget the help from the staff at the writing center and the library.

Walden has put together an incredible staff for this program. The staff at Walden gives

every student the tools and encouragement they need to succeed. I would not have

wanted to attempt this program of study at any other institution.

Lastly, I would like to thank my fellow students in every class and residency

along the way. They were a constant source of encouragement and help. I can only hope

that they would say the same about me.

i

Table of Contents

List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... iv

List of Figures ......................................................................................................................v

Section 1: Foundation of the Study ......................................................................................1

Background of the Problem ...........................................................................................1

Problem Statement .........................................................................................................3

Purpose Statement ..........................................................................................................3

Nature of the Study ........................................................................................................4

Research Question .........................................................................................................5

Hypotheses .....................................................................................................................5

Theoretical Framework ..................................................................................................6

Operational Definitions ..................................................................................................7

Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations ..............................................................10

Assumptions .......................................................................................................... 10

Limitations ............................................................................................................ 10

Delimitations ......................................................................................................... 11

Significance of the Study .............................................................................................11

Contribution to Business Practice ......................................................................... 11

Implications for Social Change ............................................................................. 12

A Review of the Professional and Academic Literature ..............................................14

Service-Profit Chain.............................................................................................. 15

CRM Market Growth ............................................................................................ 21

ii

The Emergence of CRM ....................................................................................... 22

CRM History ......................................................................................................... 23

CRM Benefits ....................................................................................................... 43

CRM Failures ........................................................................................................ 46

Problems With CRM............................................................................................. 47

CRM Definitions ................................................................................................... 50

CRM Strategy ....................................................................................................... 60

CRM Performance Measures ................................................................................ 64

CRM Success Measures ........................................................................................ 66

Transition .....................................................................................................................69

Section 2: The Project ........................................................................................................72

Purpose Statement ........................................................................................................73

Role of the Researcher .................................................................................................73

Participants ...................................................................................................................75

Research Method and Design ......................................................................................75

Research Method .................................................................................................. 75

Research Design.................................................................................................... 76

Population and Sampling .............................................................................................76

Ethical Research...........................................................................................................79

Data Collection Instruments ........................................................................................80

Data Collection Technique ..........................................................................................81

Data Analysis ...............................................................................................................82

iii

Assumptions .......................................................................................................... 84

Study Validity ..............................................................................................................87

Transition and Summary ..............................................................................................89

Section 3: Application to Professional Practice and Implications for Change ..................90

Introduction ..................................................................................................................90

Presentation of the Findings.........................................................................................90

Descriptive Statistics ............................................................................................. 91

Tests of Assumptions ............................................................................................ 92

Regression Analysis Results ................................................................................. 95

Impact on the Service-Profit Chain....................................................................... 98

Applications to Professional Practice ........................................................................102

Implications for Social Change ..................................................................................104

Recommendations for Action ....................................................................................106

Recommendations for Further Research ....................................................................108

Reflections .................................................................................................................109

Summary and Study Conclusions ..............................................................................110

References ........................................................................................................................112

Appendix A: Data Use Agreement ..................................................................................133

Appendix B: SPSS Output ...............................................................................................136

iv

List of Tables

Table 1. Summary Statistics for Research Articles Used in This Study ........................... 15

Table 2. Means (M) and Standard Deviations (SD) for Study Variables (N = 178) ........ 92

Table 3. Study Variable Correlation Coefficients and VIFs ............................................. 93

Table 4. Regression Analysis Summary for Predictor Variables ..................................... 97

v

List of Figures

Figure 1. Power as a function of sample size.................................................................... 78

Figure 2. Normal probability plot (P-P) of the regression standardized residuals. .......... 94

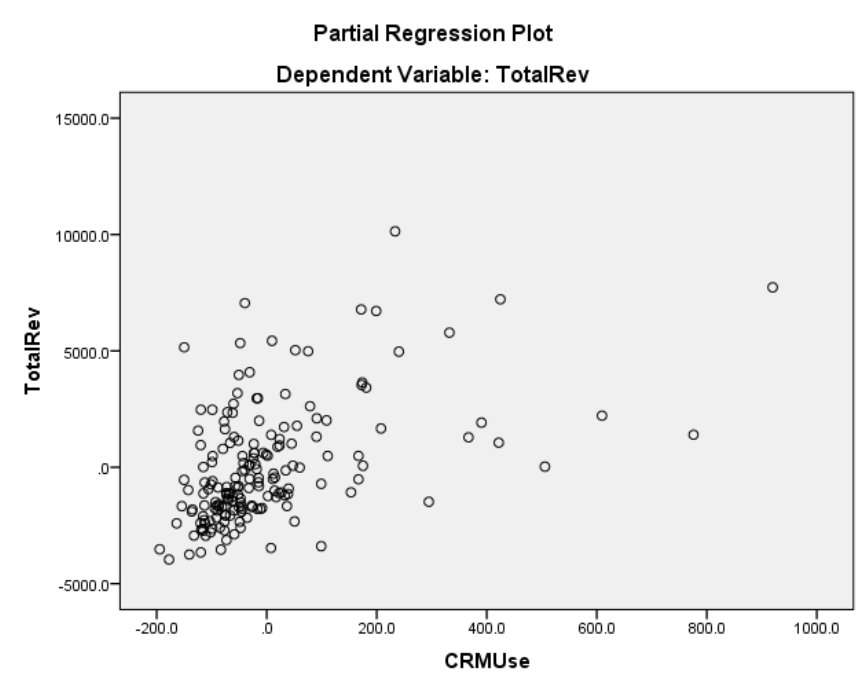

Figure 3. Scatterplot of the standardized residuals. .......................................................... 95

1

Section 1: Foundation of the Study

Business leaders realize that retaining profitable customers is essential to their

organization’s success (Herhausen & Schogel, 2013). In 2013, researchers estimated that

72% of business-to-consumer (B2C) companies listed retaining current customers as a

top priority (Verhoef & Lemon, 2013). The widespread need for organizations to retain

profitable customers is driving some of the current investment in business information

systems. Information systems help companies collect data and manage customer

relationships (Johnson, Clark, & Barczak, 2012; Oztaysi, Sezgin, & Ozok, 2011). In

Europe, 46% of chief information officers (CIO) had immediate plans to invest in

customer relationship management (CRM) systems (Verhoef & Lemon, 2013). Similarly,

in the United States, 73% of big business have already invested in CRM systems or plan

to do so in the near future (Verhoef & Lemon, 2013). The business demand for CRM

systems has fueled significant growth in an already strong industry (Greenberg, 2010;

Hassan & Parvez, 2013). However, many business leaders are questioning the need to

invest in CRM due to the high failure rate of CRM installations (Roy, 2013). Gartner

Group found that up to 70% of CRM installations showed no business benefits or

generated a loss (Li & Mao, 2012).

Background of the Problem

In the current literature on CRM usage, scholars have provided a multitude of

definitions for CRM systems. Most definitions focus on the technology portion of CRM,

specifically the information system that house the data (Vella & Caruana, 2012). A full

description of CRM should include the people and process that are part of any detailed

2

implementation (Ernst, Hoyer, Krafft, & Krieger, 2011). Using a blend of definitions

from other research, Vella and Caruana (2012) defined CRM as the integration of people,

systems, and processes to achieve customer satisfaction throughout the product life cycle.

The failure of many companies to adopt this more holistic view of CRM may be a key

reason that so many CRM implementations have failed to meet expectations (Maklan,

Knox, & Peppard, 2011). An accurate definition alone is not enough to ensure the success

of any system.

Much of the current research on CRM failures has focused on implementation

strategies. Scholars have developed a variety of implementation approaches for CRM

systems and found that no single implementation plan is always successful (Ahearne,

Rapp, Mariadoss, & Ganesan, 2012). Ahearne et al. (2012) offered a contingency

approach in order to provide the greatest opportunity for implementation success.

Ahearne et al. explained that there is no single correct approach applicable to all

organizations or situations. The concept of multiple successful strategies based on the

organizational situation is the fundamental tenant of contingency theory.

Contingency theory alone does not fill all the gaps in the current research.

Ahearne et al. (2012) called for further research to understand if CRM system usage has

any effect on firm financial performance. Much of the current CRM research focuses on

the costs of system implementation and does not address the ongoing costs or benefits of

CRM system operation. Law, Ennew, and Mitussis (2013) identified a gap in the current

research related to how CRM system operation may influence the financial performance

of the firm.

3

Problem Statement

Global CRM Project revenue topped $13 billion in 2012, and with failure rates

approaching 80%, businesses lost nearly $10.5 billion (Iriana, Buttle, & Ang, 2013; Sen

& Sinha, 2011). Experts predict that losses will continue, potentially reaching $22 billion

by 2017 (Li & Mao, 2012; Maklan et al., 2011). The general business problem is that

companies that invested heavily in CRM systems, such as Xerox, are not seeing the

expected improvement in customer satisfaction, service growth, and return on investment

(Ernst et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2012; Josiassen, Assaf, & Cvelbar, 2014). The specific

business problem is that some managers have limited knowledge of the relationship

between CRM system usage, customer satisfaction, and the company’s gross revenue

(Coltman, Devinney, & Midgley, 2011; Garrido-Moreno & Padilla-Meléndez, 2011).

Purpose Statement

The purpose of this quantitative correlational study was to examine the

relationship between CRM system usage, customer satisfaction, and gross revenue. The

independent variables were CRM system usage (X

1

) and customer satisfaction (X

2

). The

dependent variable was gross revenue (Y). The targeted population included 203 service

branches from an industrial equipment manufacturer in North America. This population

was appropriate for this study because the target company provides a representative

sample of industrial service firms in North America with a fully implemented CRM

system.

The implications for positive social change include helping companies understand

how to allocate their investment dollars. In addition, managers may use the results to

4

identify successful strategies to implement CRM systems or develop a method to justify

future investment. In addition to justifying the cost of a CRM system, firms may save

money by not investing in a CRM system if the cost exceeds the benefits. In either case,

business leaders can use a portion of the savings for sustainability projects or in

community development projects.

Nature of the Study

The main factors that affect a scholar’s choice of research methods are the

research question and data available (Fetters, Curry, & Creswell, 2013). The statistical

methods used in this study helped to identify if CRM system use has any relationship to

gross revenue. Researchers who use a quantitative method are attempting to accept or

refute a hypothesis using standard statistical analysis (Bettany-Saltikov & Whittaker,

2013). Since I sought to understand relationships using numerical methods in this study, a

qualitative approach was not appropriate. Similarly, a mixed method approach was not

appropriate since the study used only numerical data. The data for this study are

numerical in nature and lend themselves to a statistical analysis, which made a

quantitative approach the most appropriate; for these reasons, I selected a quantitative

method for this study.

A correlational design is appropriate to investigate relationships between the

independent and dependent variables (Bettany-Saltikov & Whittaker, 2013). In a

correlational design, the researcher is attempting to predict relationships and/or patterns

between the chosen variables (Aussems, Boomsma, & Snijders, 2011). A correlational

design was appropriate for this study since it was attempting to understand any

5

associations or relationships between the independent and dependent variables. Since

there was no intention of controlling any of the independent variables, experimental and

quasi-experimental designs were not appropriate for this study (Aussems et al., 2011).

Research Question

The research question is an essential element in determining the research method

(Fetters et al., 2013). Scholars should write their research question in a clear and concise

manner, purposefully worded to provide something other than a yes or no answer. In this

study, the research question explored relationships between CRM system usage, customer

satisfaction, and gross revenue. The central research question for this quantitative

correlational study was the following: What is the relationship between CRM system

usage, customer satisfaction, and gross revenue in the industrial service industry? The

primary research questions resulted in the following subquestions:

• RQ-1: What is the relationship between CRM system usage and gross revenue in

the industrial service industry?

• RQ-2: What is the relationship between customer satisfaction and gross revenue

in the industrial service industry?

Hypotheses

In quantitative correlational studies, the scholar answers the research question

through hypothesis testing (Bettany-Saltikov & Whittaker, 2013). Quantitative

researchers use statistical methods to reach conclusions in their work (Fetters et al.,

2013). In this study, I employed multiple regression analysis to test the following

hypotheses:

6

H1

o

: There is no relationship between CRM system usage and gross

revenue in the industrial service industry.

H1

a

: There is a relationship between CRM system usage and gross

revenue in the industrial service industry.

H2

o

: There is no relationship between customer satisfaction and gross

revenue in the industrial service industry.

H2

a

: There is a relationship between customer satisfaction and gross

revenue in the industrial service industry.

Theoretical Framework

Although researchers have developed multiple frameworks to evaluate business

performance within service industries, the service-profit chain has emerged as the most

popular. Heskett, Jones, Loveman, Sasser, and Schlesinger (1994) developed the service-

profit chain model and published it in their pioneering article in the Harvard Business

Review. The service-profit chain was one of the first theories to integrate operations

management concepts with human resource concepts in the service industry in an effort

to explain organizational success (Yee, Yeung, & Cheng, 2011). The service-profit chain

model establishes relationships between customer satisfaction, customer loyalty,

employee satisfaction, and firm profitability (Pantouvakis & Bouranta, 2013). Previous

studies have verified the validity of the service-profit chain. For example, Towler,

Lezotte, and Burke (2011) confirmed that the service-profit model links the following: (a)

concern for employees and concern for customers, (b) concern for customers and

customer satisfaction, (c) customer satisfaction and customer retention, and (d) customer

7

retention to firm performance. In this study, I proposed an additional variable of CRM

system usage in the service-profit chain. The intent of this study was to evaluate CRM

operation as an additional influence in the service-profit chain.

Several researchers have attempted to develop a framework to assess CRM

system performance. For example, Garrido-Moreno and Padilla-Melendez (2011)

developed a model that linked key variables including customer orientation, CRM

technology, CRM success, CRM experience, financial results, and marketing results.

Garrido-Moreno and Padilla-Melendez (2011) used an extensive review of existing

research to identify factors to use in their model and then used a survey of 311 Spanish

hotel employees to understand which factors were most significant. However, Garrido-

Moreno’s and Padilla-Melendez’s (2011) model is not sufficient for this study since it

focused on knowledge management as the primary success factor and did not consider

customer satisfaction as either a variable or result. Similarly, Hsieh, Rai, Petter, and

Zhang (2012) developed a model that linked CRM user satisfaction to employee service

quality and ultimately customer satisfaction. In another study, Wu and Lu (2012)

developed a model to link CRM operation to relationship marketing and ultimately firm

financial performance.

Operational Definitions

The following terms and phrases appear in this study. Readers who are unfamiliar

with customer relationship management can use the definitions provided to clarify terms

used in the study that are unclear. Additionally, the listing includes definitions for

8

common terms that may have different meanings in everyday use or could be confused

with similar terms in other industries.

Analytical customer relationship management (aCRM): The process of evaluating

a customer’s data to expose behavior patterns in relation to purchases, including parts of

the CRM system that focuses on the systematic collection, evaluation, and analysis of

customer data (Gneiser, 2010; Ranjan & Bhatnagar, 2011; Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012).

Analytic CRM includes technologies that store customer data and identify patterns such

as satisfaction levels, support levels, and customer segmentation (Gulliver, Joshi, &

Michell, 2013; Keramati, Mehrabi, & Mojir, 2010).

Collaborative customer relationship management: Collaborative CRM includes

systems that ensure the communication, management, and synchronization of customer

communications through specific distribution channels (Gneiser, 2010). Collaborative

CRM technologies include items such as e-mail, phone systems, faxes, website, and

forums (Keramati et al., 2010; Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012).

Customer lifetime value (CLV): A measure of the value of customer relationships,

in terms of profitability, over the length of the relationship (Kim, Park, Dubinsky, &

Chaiy, 2012). CLV uses the net present value technique to quantify the value of a

customer. Managers calculate CLV by subtracting the direct costs of the customer

relationship from the present value of expected benefits over the life of the relationship

(Gneiser, 2010; Verhoef & Lemon, 2013).

Customer relationship management (CRM): Vella and Caruana (2012) defined

CRM as the integration of people, systems, and processes to achieve customer

9

satisfaction throughout the product life cycle. CRM describes the strategic management

of customer relationships using technological tools where appropriate (Frow, Payne,

Wilkinson, & Young, 2011). The three main subcomponents of CRM are operational

CRM, analytic CRM, and collaborative CRM (Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012).

Electronic customer relationship management (eCRM): Electronic CRM is

simply CRM that includes the use of technology (Harrigan, Ramsey, & Ibbotson, 2012).

Global customer relationship management (GCRM): Kumar, Sunder, and

Ramaseshan (2011) defined GCRM as the strategic application of CRM processes and

tools across many customers in different countries.

Management CRM processes: The strategic activities that create business

intelligence and improves decision making for resource allocation, service delivery, and

product development (Keramati et al., 2010).

Operational customer relationship management (oCRM): Operational CRM

includes applications and processes that support all areas of the business that are in direct

contact with customers (Gneiser, 2010). Operational CRM technologies include

applications that support marketing, sales, and customer service (Keramati et al., 2010).

Social customer relationship management (sCRM): CRM systems that makes use

of blogs, forums, and other social media to broaden the focus of traditional CRM

(Gneiser, 2010; Trainor, Andzulis, Rapp, & Agnihotri, 2014).

Value-based customer relationship management: Gneiser (2010) defined value

based CRM as CRM that establishes a goal to build and manage a portfolio of customer

relationships, which provide maximum value for the business.

10

Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations

Assumptions

Nenty (2009) defined assumptions in a study as something that is not testable but

assumed to be true. For the purpose of this study, I assumed that the data provided by the

subject company were correct and accurate. There are no means available to verify the

accuracy of the data supplied. Since the data used are not public and only available from

internal company records, there are no external means available to validate the data.

Since the current North American Service Director for the subject equipment

manufacturer provided the data at the start of the study and is a credible source, the risk

of using erroneous data was minimal. Additionally, the service director was gathering

data from existing company records. The use of existing data sources further minimized

the risk of using inaccurate data.

The final assumptions relate to the mathematical requirements needed to use

regression analysis. Since regression analysis is a statistical procedure, certain

assumptions need to exist with the data for verification during data analysis. The

statistical assumptions for the regression model include (a) linearity between the

predictor and dependent variables, (b) no serial correlation, (c) homoscedasticity, and (d)

normally distributed errors (Williams, Grajales, & Kurkiewicz, 2013).

Limitations

Limitations are conditions out of the researcher’s control that provide bounds for

the conclusions (Nenty, 2009). The inherent limits of using a single national organization

for the study suggest that the results of this study are not necessarily transferable to other

11

groups or geographic locations. In addition, since a single division of the company uses

the CRM system under study, the results may not be transferable to the other divisions

within the same company. However, given the similarity of the equipment serviced by all

divisions within the enterprise, it is likely that the results may be transferable to other

divisions within the company and similar service companies within North America.

Delimitations

The purpose of imposing delimitations is to limit the scope of the study (Nenty,

2009). In order to complete data collection within the 1 year designated by the Walden

University Institutional Review Board (IRB), I limited the scope of the study to the North

American service branches of the subject company. Although this manufacturer has retail

service branches globally, I excluded branches outside of North America from this study.

Additionally, this manufacturer has at least three separate instances of CRM systems it

uses across various business units. However, in this study I only focused on one of the

three CRM installations. The basis for selection of the CRM system was longevity in use,

data availability, and its frequent use by employees.

Significance of the Study

Contribution to Business Practice

Several businesses have benefited from investing in CRM systems. For example,

Hassan and Parvez (2013) found that CRM systems have become a powerful marketing

tool. Marketing leaders use CRM systems as a means to communicate with and retain

existing customers. Similarly, the driving factor for CRM growth is that companies are

finding it more profitable to retain existing customers rather than attract new ones

12

(Garrido-Moreno & Padilla-Meléndez, 2011). In addition to communicating with

customers, CRM provides a means to enhance business relationships with existing

customers. Many companies see CRM systems as a tool to help them add value to

existing customers and improve customer satisfaction (Wu & Lu, 2012). However,

companies do not see the benefits expected from expensive CRM projects (Maklan et al.,

2011). Regardless of the many benefits CRM systems offer, business leaders are

questioning their value.

Existing research on CRM does not clearly identify the benefits of CRM

operation (Li & Mao, 2012). Additionally, there is little knowledge about the relationship

between CRM and customer satisfaction (Sivaraks, Krairit, & Tang, 2011). Much of the

research done on CRM systems has been in the retail goods or banking sectors. This

study will add to the body of knowledge by describing the impact of CRM systems in the

industrial service sector. The subject firm for this study manufactures and distributes

industrial products. The focus of this study is the service branches for the target business

in North America. Additionally, this research will add to the body of knowledge by

determining the impact CRM has on customer satisfaction and firm financial

performance for the target organization. The results of the study should be generalizable

to similar North American industrial service organizations.

Implications for Social Change

Traditional business theory focuses on the economic aspects of business

performance; however, the development of corporate social responsibility has highlighted

the expanded role of companies in the global community. The public expects businesses

13

to embrace social change, clean up the environment, and improve economic conditions in

their communities (Bondy, Moon, & Matten, 2012). The business case for corporate

social responsibility demonstrates how a company’s concern for social and environmental

issues contributes to the organization’s economic success (Bondy et al., 2012).

Businesses can reinvest gains from any commercial success they experience into

additional social and environmental projects. This concept substantiates that positive

social change occurs when a company’s corporate social responsibility efforts contribute

to its financial success.

This research helped to identify the economic benefits of CRM systems and this

was the most significant finding of the study. The high cost of CRM implementations

creates an expectation from business leaders to see a return on their investment.

However, researchers have found that up to 22% of CRM systems fail to meet business

leaders’ expectations, and 20% damage customer relationships (Frow et al., 2011).

Failure of a CRM system by any measure results in wasted time and money for business.

The direct investment spent on CRM systems is not the only downside for

companies if implementations fail. Managers must also contend with the cost of lost

opportunities. Money used to invest in CRM systems is not available for the business to

use for other more lucrative projects. For example, a company could invest its funds,

resources, and capital into other projects that theoretically would have produced a return.

The potential loss to the business from a failed CRM system includes the direct project

cost and the cost of not doing other income generating projects.

14

The results of this study contributed to positive social change by helping

companies understand how to allocate their investment dollars. This study helped enable

managers to identify successful strategies for CRM system implementation or to learn

how to justify the expense of a CRM system. Companies can save money by ensuring

their CRM system strategy will be successful or by choosing not to invest. In either case,

companies can use any savings to invest in their local communities or other sustainability

efforts.

A Review of the Professional and Academic Literature

The purpose of this study was to help business leaders understand what benefits

CRM system usage can have on their bottom line. Most managers believe that CRM

system use helps them serve their customers better, which leads to improved customer

satisfaction. Terpstra, Kuijlen, and Sijtsma (2012) found that improved customer

satisfaction leads to increased revenues. Many managers assume that merely using a

CRM system leads to improved customer satisfaction and increased revenue. In this

study, I hypothesized that the combination of CRM usage and customer satisfaction has a

positive impact on revenue.

The following literature review contains 11 major sections that provide an

extensive review of CRM. Table 1 contains a brief summary of the statistics relevant to

the journal articles used in this study. The literature review begins with a detailed

discussion of the service-profit chain. The next sections address CRM market growth, the

emergence of CRM from other processes, and a brief history of CRM platforms. The next

three sections shift focus to look at the benefits that CRM systems provide, some

15

examples of CRM failures, and several issues related to CRM system use. The discussion

on CRM definitions reviews the many types of CRM systems in use today and provides a

working definition for use in this study. In the discussion on CRM strategy, I provide a

detailed review of how business leaders include CRM in their overall strategy and an

example of a CRM value chain. The CRM value chain case presented in this discussion is

a synthesis of the many articles on the topic. The literature review ends with two sections

on CRM performance measures and criteria to measure CRM success.

Table 1

Summary Statistics for Research Articles Used in This Study

Frequency Percentage

Total references used that are 5 or less years old. 124 89%

Total references used that are peer reviewed. 133 96%

References used in the literature review. 100 76%

Total References 139 100%

Note. Article age refers to the number and percentage of articles that are less than 5 years

old at the expected CAO approval date. I verified the peer review for each article using

Ulrich's Periodicals Directory.

Service-Profit Chain

The service-profit chain has emerged as the primary theory to help managers

understand how employee and customer satisfaction leads to improved business

performance. Heskett et al. (1994) suggested the initial relationship later known as the

service-profit chain in 1994 (Pantouvakis & Bouranta, 2013). Other scholars have

16

suggested modifications such as the relationship that links performance outcomes to

employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty (Evanschitzky et al.,

2012). Researchers have shown that higher levels of customer satisfaction lead to repeat

business and improved margins (Oakley, 2012). The link between customer satisfaction

and improved business performance is the most studied aspect of the service-profit chain.

Additionally, studies show that satisfied customers result from interactions with happy,

loyal, and productive employees (Pantouvakis & Bouranta, 2013).

The service-profit chain has three principal components including employee

satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and business performance. Evanschitzky et al. (2012)

proposed operational investments as another essential element. Companies invest heavily

in CRM systems in an attempt to improve their operations. Although Evanschitzky et al.

considered the effects of time lags, they failed to consider the use of operational

investments as a variable in their research. The service profit chain, along with

Evanschitzky’s et al. modification provides the basis for this study with the addition of

the variable used to consider the utilization of a CRM system. A more detailed discussion

of employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and financial performance follows.

Employee satisfaction. Many managers think they already understand employee

satisfaction. For example, traditional views of employee satisfaction consider constructs

such as working conditions, compensation, and interpersonal relationships (Frey, Bayon,

& Totzek, 2013). However, it is important for managers to consider infrastructure and

training investments and the impact of these investments on employee satisfaction.

Operational investments such as employee training programs or employee development

17

programs have also had positive effects on employee satisfaction (Evanschitzky et al.,

2012). Evanschitzky, Groening, Mittal, and Wunderlich (2011) provided a simple

definition of employee satisfaction as the overall assessment of the job by the employee.

Regardless of the definition used, scholars have found a relationship between employee

satisfaction and customer satisfaction. However, the impact of CRM operation on

employee satisfaction is not apparent.

Researchers found CRM operation could have a positive or negative impact on

employee satisfaction. Law et al. (2013) claimed that employee satisfaction was a

primary outcome of CRM operation. Hsieh et al. (2012) concluded that the mandated use

of CRM might have an adverse impact on employee satisfaction. The conflicting results

in the literature reinforce the need for additional research on the overall effect of CRM

operation on the service-profit chain.

Previous research has confirmed the link between employee satisfaction and

customer satisfaction. Pantouvakis and Bouranta (2013) found that satisfied employees

exhibit positive behaviors that lead to better customer service. Evanschitzky et al. (2011)

found that employee satisfaction improves customer satisfaction and helps strengthen the

effect customer satisfaction has on customer repurchase intentions. Improved customer

repurchase intentions should lead to improved financial performance, but this is not

necessarily the case. Some researchers found no link at all between employee satisfaction

and financial performance (Evanschitzky et al., 2012). Customer satisfaction provides a

crucial link between employee satisfaction and business performance.

18

Customer satisfaction. Managers believe they already have a good

understanding of how customer satisfaction influences their business results. However, a

full understanding requires more than a basic understanding of what influences customer

perceptions. Scholars have defined customer satisfaction as a client’s sense of

contentment derived from their experience with a company as compared to their

expectation prior to interacting with the business (Chougule, Khare, & Pattada, 2013).

There are two separate conceptualizations of customer interactions in relation to customer

satisfaction. Transaction-specific customer satisfaction refers to the impact of a single

customer interaction on customer satisfaction (Chougule et al., 2013). Cumulative

satisfaction is a summation of the customer’s experiences with a company over time

(Chougule et al., 2013). Managers should seek to understand both aspects of customer

satisfaction. However, Pantouvakis and Bouranta (2013) found that service quality had a

more considerable impact on cumulative customer satisfaction. The cumulative effect of

a customer’s experience with a company over many service events does more to

influence their long-term perception of the enterprise.

Researchers have found substantial benefits to improved customer satisfaction.

For example, higher levels of customer satisfaction lead to customer retention, more

repeat business, increased gross margins, reduced acquisition costs, and improved long-

term revenues (Oakley, 2012). Increased revenues and improved cash flows are the most

significant business benefit of customer satisfaction documented in the academic

literature (Williams & Naumann, 2011). Baumann, Elliott, and Burton (2012) found that

satisfied customers are willing to pay a premium for a product or service. The existing

19

literature is clear that improved customer satisfaction results in improved financial

performance of an organization. Scholars are still researching the impact CRM may have

on customer satisfaction and business performance.

Many believe that CRM has a positive effect on performance. Business leaders

believe that CRM systems can have a positive impact on customer satisfaction by

enabling firms to customize offerings, increase the reliability of their products, and better

manage the customer relationships (Ata & Toker, 2012). One could summarize the

empirical research to suggest that CRM operation not only improves customer

satisfaction but also increases revenue, reduces labor cost, reduces lead times, and

improves quality (Ata & Toker, 2012). However, disagreement exists among scholars

regarding the benefits of CRM operations.

There are conflicting results in much of the existing research concerning the

impacts CRM operation have on customer satisfaction. There is still considerable debate

among researchers on the actual benefits of CRM operation (Verhoef et al., 2010). Many

factors other than CRM operation affect customer satisfaction and thus complicate the

debate. For example, Chougule et al. (2013) found that product quality affects customer

satisfaction by as much as 40%. Similarly, Azad and Darabi (2013) asserted that CRM

operation did not have a notable influence on the quality of service, customer complaints,

or improved revenues. It is hard to assess the impact of CRM on customer satisfaction.

Regardless of the impact of CRM, the majority of the literature suggests that higher

levels of customer satisfaction lead to improved financial performance (Steven, Dong, &

20

Dresner, 2012). The question of how CRM influences customer satisfaction, and overall

business performance remains unanswered.

Financial performance. Business leaders have developed a variety of methods to

assess performance. For example, managers in different functions use a variety of metrics

such as market share, sales growth, customer acquisition, sales activity, and win-loss

ratios to measure performance (Kumar et al., 2013). Some scholars believe that the use of

only financial measures is insufficient to explain broader organizational performance. In

an effort to provide a more comprehensive measure, Wu and Lu (2012) suggested a

three-pronged approach to measuring firm performance that included financial measures,

enterprise performance, a combination of financial and operational performance, and

organizational performance. However, the approach suggested by Wu and Lu (2012) has

failed to gain widespread use. Traditional financial measures such as revenue, net

income, earnings per share, and profitability are still the most common methods of

measuring business performance (Williams & Naumann, 2011). When CRM systems are

in use for extended periods, customer lifetime value is the most popular performance

measure (Tuzhilin, 2012). The customer lifetime value approach is gaining in popularity

but is hard to implement.

The customer lifetime value approach appeals to marketers because it provides a

strong indication of future performance. Some scholars have suggested that the best

method of evaluating a firm’s value is to sum the value of its existing and future

customers (Verhoef et al., 2010). Researchers developed the concept of CLV to describe

how to value customer relationships over the life of the firm. CLV is the sum of revenue

21

derived from a customer over their life with a firm minus the total cost of selling and

servicing that customer (Fan & Ku, 2010). The final step in calculating CLV requires

using the net present value method to account for the time value of money (Gneiser,

2010). CLV is a difficult metric for businesses to calculate because of the need to predict

customers’ future purchasing decisions (Fan & Ku, 2010). The complications in

computing CLV have limited organizations’ ability to implement it despite its popularity.

The CLV method of calculating value is becoming more popular as companies are

shifting their focus to profitable customers (Verhoef et al., 2010). CLV adds credence to

the paradigm that it is more costly to acquire a new customer than to retain an existing

one (Nguyen & Mutum, 2012). The implementation of information systems with

embedded analytics helps companies overcome many of the difficulties in implementing

CLV.

CRM Market Growth

The market for CRM systems has shifted significantly in the last 2 decades. In

2000, experts estimated the market for CRM systems between $44 and $50 billion

annually with a growth rate of approximately 15%; however, the market took a downturn

in the following years (Frow et al., 2011; Li & Mao, 2012; Maklan et al., 2011). Bull and

Adam (2011) estimated the total U.S. market size in 2008 for CRM systems at $13

billion. Some believe the decrease in market size was due to the global economic

recession. However, it appears that the market stabilized in the following years. Padilla-

Melendez and Garrido-Moreno (2013) reported the U.S. market size still at $13 billion in

2012. Market growth projections for CRM systems globally have proven to be unreliable.

22

Experts estimated the CRM market would grow anywhere from 12% to 36% in 2012

(Greenberg, 2010). Regardless of the actual change in market conditions, researchers are

not clear on what factors most affected the reduction in market size.

When CRM systems first came to market, many organizations believed that CRM

would provide a competitive advantage. Companies have invested in CRM systems since

the early 1990s to help them build stronger customer relationships and gain a competitive

edge in their markets (Kim et al., 2012). However, many CRM projects have failed to

meet the expected return on investment. For example, Yang (2012) found that 35% to

75% of CRM implementations failed to meet stakeholder expectations. Other scholars

have found similar results with typical failure rates between 50% and 70% (Frow et al.,

2011; Sundar, Murthy, & Yadapadithaya, 2012; Vella & Caruana, 2012). The high failure

rate of CRM applications has caused business leaders to question the need to invest in

these types of systems.

The Emergence of CRM

The emergence of CRM systems developed from the need for call center agents to

handle multiple customer contacts. The first CRM systems surfaced in the latter part of

the 1980s (Xu, Yen, Lin, & Chou, 2002). These early systems focused on the automation

of basic customer facing activities such as capturing sales leads or automating scripts for

customer service agents (Xu et al., 2002). Early CRM systems were transactional in

nature and relatively unsophisticated in terms of features or connectivity. The emergence

of the Internet in the mid-1990s significantly changed the CRM market. The Internet

enabled a new level of connectivity in two major areas. First, the Internet allowed access

23

to a larger user base. Second, intranets, wide area networks, and the Internet allowed

CRM systems to connect to a greater number of databases. CRM platforms based on

Internet technologies created a new market known as eCRM (Milovic, 2012; Xu et al.,

2002). The growth of eCRM platforms eventually lead to the demise of client/server

based systems (Xu et al., 2002). Web-based eCRM platforms enable consumer’s

heretofore-unprecedented access to CRM platforms while on the go.

Consumers in the new Internet age require information availability while on the

go. Consumers expect companies to have the same information available via the Internet

on computers, tablets, mobile phones, and PDAs (Milovic, 2012). New eCRM

technologies allow companies to interact with customers in ways they never could before.

Electronic CRM systems provide companies with capabilities to reach customers that did

not exist in the past (Milovic, 2012). The tools supplied by CRM and eCRM systems

have enabled a new wave of relationship marketing.

CRM History

Many people believe that CRM began with the introduction of large-scale

database technology. Although database technology undoubtedly enabled CRM growth,

the origins of CRM started in the business disciplines of marketing, strategy, and supply

chain management (Meadows & Dibb, 2012). More specifically, scholars can trace CRM

roots back to relationship-based marketing. However, CRM also has strong ties to

customer orientation and database management (Meadows & Dibb, 2012). In fact, early

implementations of CRM focused almost exclusively on technology (Meadows & Dibb,

24

2012). The view of CRM as a technology only solution may be a key reason that many

systems have failed.

Many companies lost their focus on the customer as they sought new technology.

The initial connection to database technology caused many users to concentrate more on

the technology rather than how to enable improved customer relationships (Frow et al.,

2011). The technology focus of the first CRM efforts, coupled with companies’ desire to

succeed, led to significant investments in CRM platforms. Between the years of 2000 and

2005, companies spent a combined $220 billion on CRM solutions (Maklan et al., 2011).

Research suggests that this was not money well spent. Scholars have found that 22% of

CRM systems implemented before 2008 have delivered disappointing results, and 20%

even damaged customer relationships (Frow et al., 2011). The misguided focus on

technology versus the balanced approach including people and processes may be a

fundamental reason that CRM systems fail.

Timeline. The history of CRM systems starts in the field of marketing.

Researchers traced the earliest origins of CRM systems to the field of relationship

marketing and the works of Berry in 1983 (Gneiser, 2010). Yeager et al. (2011) argued

that CRM started much earlier with the use of random digit dialing telephone surveys in

the 1970s. The first telephone surveys bear little resemblance to the current definition of

CRM. Abdullateef and Salleh (2013) found that the real growth of CRM started at the

beginning of the 1990s with the introduction of sales automation applications and the

expansion of call centers. Standard software applications, or platforms, sparked the real

growth of the CRM market. The release of commercial hardware and software solutions

25

by vendors such as Siebel Systems fueled the growth seen in the late 1990s (Saarijarvi,

Karjaluoto, & Kuusela, 2013). Commercial CRM systems came with prepackaged

applications such as sales force automation and customer support. Prepackaged

applications provided companies with system based best practices that drove

improvements in the management of sales and customer service functions. With the

implementation of commercial CRM applications, companies were able to collect vast

amounts of data on their customer’s preferences and buying habits.

With large amounts of newly obtained customer data, marketers quickly sought

new ways to use the data for strategic advantage. The availability of large quantities of

customer data spawned the idea of one-to-one marketing and mass customization in the

early 1990s (Nguyen & Mutum, 2012). Companies quickly learned that collecting and

acting on customer data could help them acquire and retain profitable customers (Nguyen

& Mutum, 2012). This need generated a new branch of CRM known as analytic CRM.

The promise of analytic CRM is that it can help convey the right offer to the right

customers at the right time (Verhoef et al., 2010). Managers’ use of analytic CRM

enabled them to turn customer data into information they could use to find new customers

or improve relationships with existing customers.

In the early to mid-2000s, a new generation of CRM began to emerge known as

social CRM or CRM 2.0 (Greenberg, 2010). The emergence of popular social networks

such as Facebook, MySpace, Twitter, and others helped develop new methods for

companies to communicate and collect information from their customers. Researchers

found that the adult use of social media grew from 8% in 2005 to over 35% in 2008

26

(Greenberg, 2010). The purpose of social CRM is to engage customers in collaborative

conversations and improve customer relationships (Trainor et al., 2014). Social CRM

expands the available data to CRM applications and allows marketers a new channel to

communicate with customers more effectively.

Marketing. A strong relationship exists between CRM applications and the

discipline of marketing. Schniederjans, Cao, and Gu (2012) suggested that the capability

of CRM applications to profile customers is as important as product, price, promotion,

and place, better known as the four Ps of marketing. Building and managing the customer

relationship is essential to marketing. CRM technology enables companies to develop

better marketing strategies and allows execution of targeted campaigns that are more

efficient because of integrated customer data (Chang, Park, & Chaiy, 2010). Additionally,

CRM technology enables companies to improve their marketing capabilities by allowing

employees to achieve objectives faster and more thoroughly.

Traditional marketing management has focused on manufactured and packaged

consumer products for mass distribution. However, the marketing trend changed in the

early 2000s from a product-centered model to a customer-centered model (Xu et al.,

2002). The customer-centered model forced companies to focus more on the services

their customers desired rather than manufacturing products. The change in economies to

a service base caused a similar shift to services marketing (Gummesson, 2002). Service

marketing is similar to relationship marketing and focuses on the interaction between

customers and suppliers (Gummesson, 2002). Additionally, services marketing stress the

importance of personal relationships with customers and the importance of execution at

27

the point of the service encounter (Gummesson, 2002). CRM systems provided new

methods for companies to improve their service marketing efforts.

Transaction marketing. Early marketing efforts focused on increasing the

number of customer interactions or transactions. Transaction marketing refers to the

traditional view of marketing where the focus was on individual transactions between

buyers and sellers (Gneiser, 2010). Transactional marketing grew from the division and

specialization of labor that resulted in a diverse collection of traded goods and services

(Layton, 2011). Companies could grow their business by attracting additional customers

for similar transactions. What began as simple transactions between individuals grew

quickly into intricate patterns of trade involving entire communities, which spawned

markets (Layton, 2011). Transaction marketing describes a similar set of buyers and a

single or multiple sellers that engage in economic exchanges with limited knowledge

(Layton, 2011). The concept of transaction marketing did little to improve customer

relationships or improve customer loyalty. Relationship marketing has largely shifted the

marketing paradigm of transaction marketing from a focus on customer acquisition and

distinct transactions to long-term customer relationships with customized products

(Gneiser, 2010). However, even without a shift to relationship marketing, CRM systems

have several benefits in a transactional environment.

A significant advantage of CRM systems is its ability to improve the efficiency of

service agents during customer interactions. CRM systems can increase independent

transactions by reducing transaction times and improving payment methods (Xu et al.,

2002). The advent of online and mobile devices allow customers to execute various

28

transactions on their own. Mobile devices, in particular, enable customers to carry out

transactions at their convenience from virtually any location (Awasthi & Sangle, 2013).

CRM systems have the added benefit of reducing transaction costs and improving the

flow of information between the company and its suppliers (Xue, Ray, & Sambamurthy,

2013). Previous CRM researchers focused on reducing the cost of each customer

interaction or transaction cost economics (Xue et al., 2013). However, the cost savings

related to transaction economics fail to describe the full financial benefits of a CRM

system.

Organizations need a more holistic description of the full financial impact of

CRM system usage. Market logic tends to be the dominant theory in business research

and focuses on the relationships that produce the greatest financial gain in any financial

transaction (Bondy et al., 2012). However, even market logic fails to account for the full

benefit from CRM use. CRM provides organizations with an alternative strategy that

creates greater financial performance (Keramati et al., 2010). The resource-based view

provides a framework to understand how CRM provides economic value (Keramati et al.,

2010). The resource-based view has become the dominant methodology to describe

economic value.

Resource-based view. Early researchers on the resource-based view attempted to

understand competitive advantage. Scholars initially developed the resource-based view

to help understand how companies can create and maintain a competitive advantage (Fan

& Ku, 2010). However, companies cannot market resources; they must be able to convert

resources into products or capabilities. The resource-based view suggests how efficiently

29

a firm converts resources into capabilities will determine its performance (Mohammed &

Rashid, 2012; Trainor et al., 2014). Resources are tangible or intangible factors that a

firm can use to achieve its objectives while capabilities are repeatable skills that a

company uses to accomplish its operations (Chang et al., 2010). The resource-based view

sees the company’s resources as valuable and specific to the firm. In order to maintain a

competitive advantage the company’s resource must be unique, valuable, rare, difficult to

imitate, and nonsubstitutable (Keramati et al., 2010). The resource-based view allowed

companies to make the link between resources and strategic plans.

The resource-based view is the dominant theory in strategic management

(Keramati et al., 2010). Business leaders use theories developed by the resource-based

view to justify new investments. The resource-based view provides a theoretical basis

that helps explain how information technology affords benefits to the organization over

time (Shanks & Bekmamedova, 2012). The resource-based view allowed scholars to

quantify aspects of human resources that were widely unaccounted for in prior theories.

Human resources are arguably the most important resource in any company.

Proponents of the resource-based view believe that businesses can expand into other

markets if they have unique, relevant, and unparalleled resources across a broad range of

markets (Xue et al., 2013). Kim, Jeon, Jung, Lu, and Jones (2012) found that the firm’s

human resources are essential to achieving a competitive advantage. For example,

Ahearne et al. (2012) saw that salespeople have dynamic capabilities that enable the

company to react quickly to customer needs and, for this reason, they provide a

competitive advantage.

30

The resource-based view provides the framework that ties human resources to

technology resources that combine to provide a competitive advantage. Azad and Darabi

(2013) defined CRM systems as infrastructural resources in line with the resource-based

view. Wang (2013b) argued that CRM practices could provide rare, valuable, and

difficult to imitate resources that could provide the company with a distinct competitive

advantage. In order to maintain a competitive advantage, the company must not only

guard core capabilities, but they must also protect critical resources and assets (Graf,

Schlegelmilch, Mudambi, & Tallman, 2013). The resource-based view allows researchers

to explain the relationship between people, processes, and technology that help CRM

systems achieve success.

The resource-based view has proven particularly useful in explaining the financial

outcomes of certain strategic investments. Researchers have applied the resource-based

view to CRM in order to help explain the productivity paradox of information technology

(Keramati et al., 2010). The productivity paradox refers to the problem company’s face

when they invest in information technology and see little to no improvement in firm

performance (Keramati et al., 2010). Researchers see the resource-based view as the most

appropriate method available to investigate the discrepancy between CRM investment

and firm performance. The preference for the resource-based view is due to its close tie to

marketing, information technology, and the previous application of the resource-based

view to both disciplines (Keramati et al., 2010). Scholars can take advantage of previous

research on the resource-based view and apply the learnings to current technology

investments.

31

Relationship marketing. The goal of most CRM strategies is to increase a client’s

income, satisfaction, and the company’s profit (Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012). CRM systems

are one method companies use to improve customer relationships and in turn customer

satisfaction and profits. CRM systems have three separate pieces. First, operational CRM

includes the customer facing software (Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012). Second, analytical CRM

stores customer information and provides reporting (Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012). Third,

collaborative CRM includes communication tools with end users such as e-mail,

telephone, and websites (Tohidi & Jabbari, 2012). These systems work together to

provide the company with the information that brings value to the customer and improves

customer relationships.

Creating value for customers is the first step in creating long-term and profitable

relationships. Companies develop relationship-marketing strategies to retain high-value

customers and maximize customer value (Ashley, Noble, Donthu, & Lemon, 2011).

Researchers believe that firms can use relationship marketing to generate repeat

purchases by encouraging customers to develop a psychological dependence on their firm

(Chen & Chen, 2013). CRM systems are a critical component of many businesses’

relationship marketing efforts. Numerous companies use CRM systems to improve their

relationship marketing efforts (Chen & Chen, 2013). Academics use the terms CRM and

relationship marketing interchangeably due to their interconnected history (Shafia,

Mazdeh, Vahedi, & Pournader, 2011). However, CRM and relationship marketing are not

the same.

32

Relationship marketing is a recent phenomenon in the business world. However,

scholars agree that CRM developed from relationship marketing (Ata & Toker, 2012).

Relationship marketing, unlike transaction marketing, focuses on developing and

maintaining continuous and profitable relationships with customers (Ata & Toker, 2012;

Johnson et al., 2012; Sen & Sinha, 2011). Relationship marketing changes the focus of

marketing away from products and focuses it squarely on customer relationships (Wang

X. L., 2012). Scholars identified developing relationships with new customers as a

primary goal of relationship marketing. Companies who engage in relationship marketing

develop relationships with clients based on quality, dialog, innovation, and learning

(Johnson et al., 2012; Nguyen & Mutum, 2012). However, Su et al. (2010) argued that

the foundation of relationship marketing is trust. Before companies can gain a customer’s

loyalty, they must first gain their trust.

Many of the marketing methods in common use today are a result of relationship

marketing and CRM. For example, marketing campaigns such as loyalty card programs,

company credit cards, personalized offers, email lists, and discount offers had their

beginnings in certain elements of relationship marketing (Ashley et al., 2011). Some

scholars describe CRM as relationship marketing targeted at the individual customer’s

needs (Yang, 2012). CRM platforms provide the information that enables many of the

now common marketing campaigns. The phrase information-enabled relationship

marketing describes how CRM provides an additional source of value creation and a new

growth enabler (Sundar et al., 2012). CRM systems are a primary component of

information-enabled relationship marketing.

33

Base of the pyramid. Relationship marketing has emerged as a key strategy for

organizations creating products targeted at the world’s poorest inhabitants at the base of

the pyramid. The base of the pyramid refers to the more than 4 billion consumers whose

annual income is less than $1,500 U.S. annually (Chikweche & Fletcher, 2013). Some of

the world’s poorest people make up the population at the base of the pyramid. The

majority of people at the base of the pyramid live in countries such as Sub-Saharan

Africa, South Asia, East Asia, and certain countries in Latin America (Chikweche &

Fletcher, 2013). Previous marketing strategies have largely ignored populations in poorer

countries. Schrader, Freimann, and Seuring (2012) found that much of the research on

markets at the base of the pyramid focused on corporate social responsibility. However,

recently scholars believe that consumers at the base of the pyramid rely more on social

networks and have unique needs from a supply chain perspective (Schrader et al., 2012).

The type of communication in markets with lower income participants makes them strong

candidates for relationship marketing strategies and CRM technologies.

Communication at the base of the pyramid is largely via person-to-person

interaction. The person-to-person connections provide a significant opportunity for

organizations to use social networks to enhance their marketing efforts. Social networks

are an important communication process at the bottom of the pyramid (Chikweche &

Fletcher, 2013). Social exchange theory may provide a link between social networks and

successful marketing strategies at the base of the pyramid. Social exchange theory

describes how actors in a relationship make investments in the relationship that

constitutes a commitment to the other party (Roy, 2013). The primary tenant of social

34

exchange theory is to prove oneself trustworthy and hope the other party reciprocates.

Social exchange theory matches the underlying premise of relationship marketing that is

to develop mutually beneficial relationships between a company and its customers (Roy

& Eshghi, 2013). Trust is a fundamental requirement when marketing products at the

base of the pyramid.

Roy and Eshghi (2013) found that the best relationship marketing strategy was

one of customer advocacy. Companies can build more trust and loyalty from customers

by keeping the customer’s best interest in mind. Roy (2013) found the market

mechanisms to optimize customer advocacy was the company’s focus on customer

success, increasing customer involvement, development of knowledge sharing

partnerships, and full transparency with customers. A robust CRM strategy provides a

means to achieve the goals laid out by a customer advocacy approach. CRM systems can

provide significant benefits to firms that target the base of the pyramid, particularly if

they include Social CRM.

CRM technology. Many view CRM solutions as a purely technical endeavor. For

the purpose of this study, CRM technology refers to the technical, or information

technology-based solutions that improve communication and information exchange

between the company and its customers (Ernst et al., 2011). Scholars should highlight the

significant differences between the technology used in CRM and the people and

processes that make up the entire CRM concept. The technology portion of a CRM

system consists of three fundamental parts (Keramati et al., 2010). The first part includes

technologies that allow two-way communication between the company and its customers.

35

The second part includes technologies that facilitate efficient internal operations between

different functions such as sales, operations, and customer service. The third part includes

technologies that provide the business with the ability to analyze data and make decisions

based on the analysis. All parts of a CRM system fit the overall system classification of

business intelligence systems. Business intelligence is the set of skills a company needs

to extract useful data from storehouses that provide insightful information on customer

needs (Malthouse, Haenlein, Skiera, Wege, & Zhang, 2013). Modern business

intelligence systems are blurring the lines between what used to be clear product

architectures such as ERP, CRM, and communications systems.

Business intelligence systems focus heavily on integration and are mostly

concerned with presenting information to decision makers. Business intelligence systems

provide decision makers with the right data at the appropriate time and in a format that

allows them to make the best decisions (Hou, 2012). Business intelligence technologies

provide the basis for CRM systems, which then allow a customer-focused strategy

(Alshawi, Missi, & Irani, 2011). In some installations, business intelligence systems

provide the linkage to stand-alone systems that allow integration of data sources. Industry

experts classify business intelligence systems as part of the family of Enterprise

Information and Communication Technologies (Alshawi et al., 2011). One example of

the use of business intelligence systems to enhance customer relationships via CRM is

the mining of data on customer complaints. If employees can analyze customer

complaints to gain more knowledge about customers, they can provide valuable business

36

intelligence for the organization (Galitsky & De La Rosa, 2011). Business intelligence

systems rely heavily on networking technologies.

Networking technologies enable communication between critical parts of the

enterprise infrastructure including CRM systems. The use of the Internet, intranet, and

extranet communications allows companies to carry out business-to-business, business-