National Vital

Statistics Reports

Volume 73, Number 1 January 31, 2024

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Health Statistics

National Vital Statistics System

Shifts in the Distribution of Births by

Gestational Age: United States, 2014–2022

by Joyce A. Martin, M.P.H., and Michelle J.K. Osterman, M.H.S.

Abstract

Objectives—This report presents changes in the distribution

of singleton births by gestational age in the United States for

2014–2022, by maternal age and race and Hispanic origin.

Methods—Data are based on all birth certificates for

singleton births registered in the United States from 2014 to

2022. Gestational age is measured in completed weeks using the

obstetric estimate and categorized as early preterm (less than

34 weeks), late preterm (34–36 weeks), total preterm (less than

37 weeks), early term (37–38 weeks), full term (39–40 weeks),

and late- and post-term (41 and later weeks). Data are shown

by maternal age and race and Hispanic origin. Single weeks of

gestation at term (37–41 weeks) are also examined.

Results—Despite some fluctuation in most gestational age

categories during the pandemic years of 2020–2022, trends from

2014 to 2022 demonstrate a shift towards shorter gestational

ages. Preterm and early-term birth rates rose from 2014 to

2022 (by 12% and 20%, respectively), while full-term and late-

and post-term births declined (by 6% and 28%, respectively).

Similar shifts for each gestational age category were seen across

maternal age and race and Hispanic-origin groups. By single

week of gestation at term, the largest change was for births at 37

weeks (an increase of 42%).

Keywords: preterm • early- and full-term births • age of mother •

race and Hispanic origin • National Vital Statistics System

Introduction

The rate of preterm birth in the United States rose by more

than one-third from 1981 to 2006 (1). This rise prompted concern

and a heightened awareness of the morbidities associated with

births delivered at 34–36 weeks of gestation, or late preterm.

Late preterm births comprise about 70% of all preterm births and

were the largest contributor to the overall preterm increase over

the period (1–3). Subsequently, the greater vulnerability of births

delivered at 37–38 weeks (referred to as early term) compared

with those born at 39–40 weeks (full term) also became evident

(4) and national organizations such as the March of Dimes, the

National Institute for Child Health and Human Development, the

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and the American College

of Obstetricians and Gynecologists began to champion the

prevention of nonmedically indicated preterm and early-term

deliveries (4). Late preterm and early-term births declined for

several years from 2007 to 2014, but have been on the rise in

recent years (1,5,6).

This report describes changes in the gestational age

distribution of singleton births from 2014—the year when the

most recent low rates in preterm and early-term birth rates

occurred—to 2022 for all births and by maternal age and race

and Hispanic origin.

Methods

This report is based on final data from the natality data

file from the National Vital Statistics System for 2014–2022.

Information from the vital statistics natality file is derived from

birth certificates and includes information for all births occurring

in the United States (7). This report describes changes in

gestational age distribution for 2014–2022. The most recent

lows in preterm and early-term birth rates occurred in 2014.

Singleton births are births in pregnancies for which only

one fetus is delivered live at any time during the pregnancy.

This analysis is restricted to singleton births because multiple

births tend to be born at earlier gestational ages than singletons,

and changes in the rate of multiple births can impact overall

gestational age distribution. Gestational age is based on the

obstetric estimate, defined as the best estimate of the infant’s

gestational age in completed weeks based on the clinician’s final

estimate of gestation at delivery (7).

Preterm births are defined as births delivered before 37

completed weeks of gestation; early preterm births are those

delivered at less than 34 completed weeks of gestation and late

NCHS reports can be downloaded from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm.

2 National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 73, No. 1, January 31, 2024

preterm births are those delivered at 34–36 completed weeks.

Early-term births are those delivered at 37–38 completed

weeks, full-term births are those delivered at 39–40 completed

weeks, and late- and post-term births are those delivered at 41

completed weeks and later (see Figure 1). Births are examined by

these gestational age categories and by single week of gestation

for weeks 37–41 to better identify changes seen in the broader

categories. Rates are calculated per 100 births. Relative percent

changes are shown in Table and Tables 1 and 2 for the full

reporting period of 2014–2022 and for each year between 2019

and 2022 (2019 to 2020, 2020 to 2021, and 2021 to 2022) to

better describe changes for the year before and each year during

the COVID-19 pandemic, as changes in birth outcomes have

been shown over this period (6). Gestational age was missing

for less than 1% of all births and for births to Black non-Hispanic

(subsequently, Black), Hispanic, and White non-Hispanic

(subsequently, White) mothers for each year of the study period

of 2014–2022.

Race and Hispanic origin are reported independently on the

birth certificate and are self-reported by the mother. Data for

2014 and 2015 are based on the bridged race of the mother; data

for 2016–2022 are single race (7). Where race of the mother

is not reported, it is imputed based on the race of the father if

known, or according to the race of the mother on the preceding

record with a known race of mother. In 2022, race of mother

was imputed for 7.6% of births. Hispanic origin was missing for

1% of records for 2022. Data shown by Hispanic origin include

all people of Hispanic origin of any race. Data for non-Hispanic

people are shown separately for single-race groups Black and

White. Due to small numbers, data for other race and Hispanic-

origin groups are not shown.

References to single-year changes in rates indicate that

differences are statistically significant at the 0.05 level based on

a two-tailed z test. Evaluation of long-term trends was conducted

using the Joinpoint Regression Program (8). Computations

exclude records for which information is unknown.

Results

Preterm births (less than 37 weeks of gestation)

The preterm birth rate rose 12% from 2014 to 2022, from

7.74% to 8.67%. The rate rose an average of 2% annually

from 2014 to 2019 (8.47%) and then fluctuated through 2022,

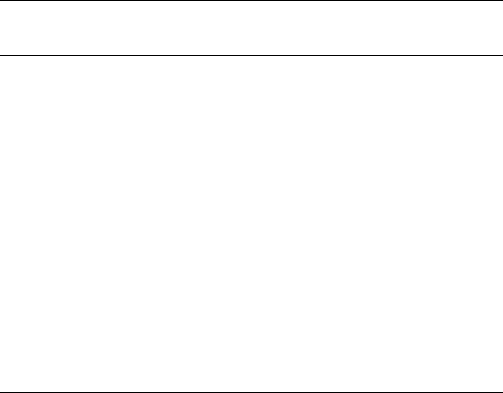

Figure 1. Percent distribution of singleton births, by gestational age: United States, 2014–2022

NOTES: Significant changes for all gestational age categories and years (p < 0.05). Singleton births only. Preterm is less than 37 weeks of gestation, early term is 37–38 weeks, full term is

39–40 weeks, and late and post-term is 41 weeks and later. Totals may not add to 100 because of rounding.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, natality data file.

Full termEarly termPreterm Late and post-term

Percent

7.74

7.82

8.02

8.13

8.24

8.47

8.42

8.76

8.67

24.31

24.56

25.07

25.59

26.18

26.99

27.46

28.53

29.07

60.76

60.47

59.93

59.47

59.17

58.92

58.83

57.71

57.11

7.20

7.15

6.97

6.81

6.41

5.62

5.29

5.01

5.15

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 73, No. 1, January 31, 2024 3

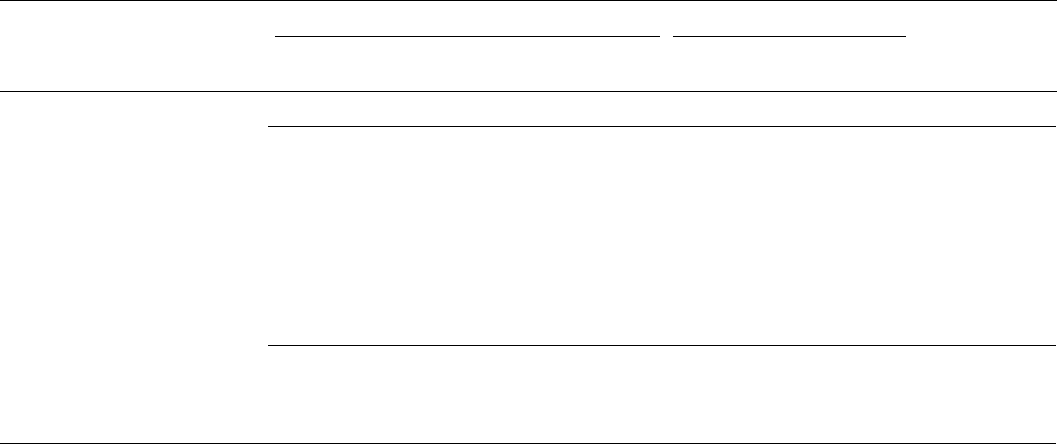

Figure 2. Percent change in gestational age category, by age of mother: United States, 2014 and 2022

NOTES: Significant changes for each age group (p < 0.05). Singleton births only. Preterm is less than 37 weeks of gestation, early term is 37–38 weeks, full term is 39–40 weeks, and late

and post-term is 41 weeks and later.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, natality data file.

-20

-30

-40

-50

-60

-10

0

10

20

30

Younger than 20 20–29 30–39 40 and older

Percent

Full termEarly termPreterm Late and post-term

9

10

14

16

18

19

20

22

-5 -5

-7

-9

-32

-27 -27

-52

declining 1% in 2020 (8.42%), increasing 4% in 2021 (8.76%),

and declining 1% in 2022 (8.67%) (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Rates for both early and late preterm births rose from 2014

to 2022 (Table 1). The rate of early preterm births increased 4%

from 2014 to 2022, from 2.07% to 2.16%, and generally rose

from 2014 to 2019 (2.14%), declined in 2020 (2.11%), and

fluctuated from 2020 to 2022. The late preterm rate increased

15% from 2014 to 2022, from 5.67% to 6.51%, and rose

by an average of 2% annually from 2014 to 2019 (6.32%),

was essentially unchanged from 2019 to 2020 (6.30%), and

fluctuated from 2020 to 2022.

By maternal age

Preterm birth rates increased for each 10-year maternal age

group from 2014 to 2022, ranging from 9% (age 20 or younger)

to 16% (age 40 and older) (Table 2, Figure 2). Rates generally

rose steadily for each group from 2014 to 2019 (the trend for

mothers age 20 or younger was less consistent) and fluctuated

from 2019 to 2022.

Early preterm births increased for each 10-year maternal

age group for 2014–2022, ranging from 3% (ages 20–29 and

age 40 and older) to 6% (ages 30–39); however, the increase for

mothers age 40 and older was not significant. Late preterm birth

rates also rose for each age group from 2014 to 2022; increases

ranged from 11% to 21%.

By maternal race and Hispanic origin

Preterm birth rates rose for the three largest race and

Hispanic-origin groups from 2014 to 2022, from 11% for

both Black and White mothers to 13% for Hispanic mothers

(Table 1, Figure 3). The preterm rate for Black mothers increased

each year from 2014 (11.12%) to 2021 (12.51%), and then

declined in 2022 (12.34%). The preterm birth rate for White

mothers increased 11% from 2014 to 2022, rising from 6.90%

to 7.64%; the rate for Hispanic mothers increased 13%, from

7.72% to 8.72%. Rates for White and Hispanic mothers increased

steadily through 2019 and then fluctuated from 2019 to 2022.

Increases in early and late preterm rates were seen for each

of the three race and Hispanic-origin groups from 2014 to 2022.

Early preterm birth rates rose 2% for Black mothers (from 3.88%

to 3.97%), 3% for births to White mothers (1.64% to 1.69%),

and 5% for births to Hispanic mothers (2.02% to 2.13%). Late

4 National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 73, No. 1, January 31, 2024

Figure 3. Percent change in gestational age category, by race and Hispanic origin of mother: United States, 2014 and

2022

NOTES: Significant changes for each age group (p < 0.05). Singleton births only. Preterm is less than 37 weeks of gestation, early term is 37–38 weeks, full term is 39–40 weeks, and late

and post-term is 41 weeks and later.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, natality data file.

-20

-30

-40

-10

0

10

20

30

Black, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Hispanic

Percent

Full termEarly termPreterm Late and post-term

11

21

-9

-31

13

11

15

22

-6

-5

-24

-28

preterm rates increased 13%–16% from 2014 to 2022 for the

three groups, from 7.24% to 8.37% for Black mothers, 5.26%

to 5.96% for White mothers, and 5.70% to 6.59% for Hispanic

mothers.

Early-term births (37–38 weeks of gestation)

Births delivered early term increased 20% from 2014 to

2022 (Table 1 and Figure 1), from 24.31% to 29.07%. Early-term

rates rose by an average of 2% annually from 2014 to 2022.

By maternal age

The early-term birth rate rose by 18%–22% across the

10-year age groups from 2014 to 2022; increases were seen for

each age group in each year of the 8-year study period, although

the increase between 2019 and 2020 for mothers age 20 or

younger was not significant (Table 2, Figure 2).

By maternal race and Hispanic origin

Among Black mothers, the early-term birth rate rose 21%

from 2014 (26.93%) to 2022 (32.71%), with increases seen for

each year (Table 1, Figure 3). Early-term births to White mothers

also rose each year from 2014 (22.48%) to 2022 (27.34%), for a

total rise of 22%. Early-term births to Hispanic mothers rose 15%

from 2014 (26.14%) to 2022 (29.94%), also rising each year.

Full-term births (39–40 weeks of gestation)

Births delivered full term declined 6% from 2014 (60.76%)

to 2022 (57.11%). Rates declined by an average of less than 1%

each year from 2014 to 2022, with larger declines for 2020–2022

(Table 1, Figure 1).

By maternal age

Over the 8-year study period, full-term birth rates declined

for mothers in each 10-year age group, ranging from 5% (for age

20 or younger and ages 20–29) to 9% (ages 40 and older) for

National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 73, No. 1, January 31, 2024 5

mothers in each 10-year age group (Table 2, Figure 2). Full-term

births generally declined for each age group each year throughout

the study period, although not all declines were significant.

By maternal race and Hispanic origin

Full-term births to Black mothers declined 9% from 2014

(56.08%) to 2022 (50.90%), trending downward by 1%–2%

each year (Table 1, Figure 3). Among White mothers, full-term

births also declined each year for a total decline of 5% from

2014 (62.48%) to 2022 (59.19%). Full-term births to Hispanic

mothers declined 6% from 2014 (59.96%) to 2022 (56.63%),

declining for most years over the period.

Late- and post-term births (41–42 and later

weeks of gestation)

Late- and post-term births declined 28% from 2014 to 2022,

from 7.20% to 5.15%. Late- and post-term births declined each

year from 2014 to 2021 by an average of 5% each year, and then

increased 3% in 2022 (Table 1, Figure 1).

By maternal age

Rates of late- and post-term births declined for each 10-year

age group, ranging from 32% (age 20 or younger) to 52% (ages

40 and older) (Table 2, Figure 2). Age-specific rates generally

declined for each year from 2014 to 2021 (the decline for

mothers age 40 and older from 2020 to 2021 was not significant)

and then rose in 2022 for each group except for mothers age 40

and older, for whom the rate declined.

By maternal race and Hispanic origin

The rate of late- and post-term births to Black mothers

declined 31% from 2014 (5.87%) to 2022 (4.05%) (Table 1,

Figure 3). The rate generally declined through 2021 (3.86%) and

rose in 2022 (4.05%). Among White mothers, late- and post-

term births declined 28% from 2014 (8.14%) to 2022 (5.83%);

rates generally declined through 2021 and rose in 2022. A similar

pattern was seen for Hispanic mothers, for whom late- and post-

term births declined 24% from 2014 (6.17%) to 2022 (4.71%).

Early-, full-, and late-term births by single

week of gestation

Early-term births delivered at 37 weeks rose each year from

2014 (8.17%) through 2022 (11.63%), for a total increase of

42% (Table, Figure 4). Births delivered at 38 weeks generally

increased each year from 2014 (16.13%) to 2022 (17.45%), for

a total rise of 8%.

Full-term births at 39 weeks fluctuated, but the trend was

essentially unchanged from 2014 through 2022 (from 38.71%

to 38.84%); the rate increased by 3% from 2014 through 2020

(40.03%) and declined in 2021 (39.61%) and 2022.

In contrast, births at 40 weeks declined 17% from 2014 to

2022, from 22.05% to 18.26%. The rate declined by an average

of 3% annually from 2014 to 2021 (18.10%) and then increased

1% in 2022.

Births at 41 weeks, which comprise most late- and post-

term births (94%), declined 28% from 2014 (6.77%) to 2022

(4.88%). Births at 41 weeks generally declined from 2014

through 2021 (4.76%) and then rose in 2022. Births at 42 weeks

of gestation and later declined 37% from 2014 (0.43%) to 2022

(0.27%); as with the trends for 41 weeks, the rate generally

declined through 2021 (0.25%) and rose in 2022.

Discussion

This report describes shifts from 2014 to 2022 in the

gestational age distribution of newborns towards births delivered

at less than full-term. Over this 8-year period, the percentages of

births delivered preterm and early-term rose by 12% and 20%,

respectively, while the percentage of full-term births declined 6%

and late- and post-term births declined by 28%. Despite some

fluctuation in rates of preterm, full-term, and late- and post-term

births during the pandemic years of 2020–2022, overall trends

continued upward for preterm and downward for full-, late-,

and post-term births; early-term births rose steadily throughout

the entire study period. Similar trends for each gestational age

category were seen across maternal age and race and Hispanic-

origin groups.

Recent changes in preterm birth rates in the United States

have been documented (5,6,9,10); less has been published on

trends in early-term births. Analysis of early-term births by single

week of gestation reveals that the largest changes occurred

among births at 37 weeks, up 42% from 2014 to 2022. Births at

38 weeks also rose, but to a lesser degree (8%). Full-term births

at 39 weeks were essentially unchanged from 2014 to 2022, but

births at 40, 41, and 42 and later weeks declined by 17%, 28%,

and 37%, respectively.

Table. Percentage of singleton births, by week of gestation:

United States, 2014–2022

Year 37 38 39 40 41

42 and

later

Percent

2022. . . . . . . . . 11.63 17.45 38.84 18.26 4.88 0.27

2021. . . . . . . . . 11.23 17.30 39.61 18.10 4.76 0.25

2020. . . . . . . . . 10.54 16.92 40.03 18.80 5.04 0.25

2019. . . . . . . . . 10.13 16.86 39.51 19.40 5.36 0.26

2018. . . . . . . . . 9.58 16.60 38.73 20.44 6.11 0.31

2017. . . . . . . . . 9.16 16.43 38.47 21.00 6.47 0.34

2016. . . . . . . . . 8.77 16.30 38.54 21.39 6.61 0.36

2015. . . . . . . . . 8.40 16.16 38.60 21.87 6.75 0.41

2014. . . . . . . . . 8.17 16.13 38.71 22.05 6.77 0.43

Percent change

2019–2020. . . . 4 † 1 -3 -6 -3

2020–2021. . . . 7 2 -1 -4 -6 ‡0

2021–2022. . . . 4 1 -2 1 3 7

2014–2022. . . . 42 8 † -17 -28 -37

† Less than 0.5.

‡ Not significant at p < 0.05.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, natality

data file.

6 National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 73, No. 1, January 31, 2024

Although infants born preterm are at highest risk of

morbidity and mortality, early-term birth is associated with

poorer outcomes compared with full-term birth, and differences

in outcomes are seen across the single-week full-term spectrum

(11–13). According to the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists, the neonatal risks of preterm and early-

term birth are well-established (14). In 2021, infant mortality

rates declined by more than one-third each successive week of

gestational ages 37–39 weeks (from 4.03 per 1,000 to 2.55 to

1.64) (15). Increases in births delivered preterm and early term

were observed for all maternal age groups from 2014 to 2022.

Although the largest changes were seen for mothers age 30 and

older, the percent change for births delivered at less than full

term ranged only from 15% (for the youngest mothers) to 20%

(for the oldest mothers).

Increases in preterm and early-term birth were also seen

for each of the race and Hispanic-origin groups studied from

2014 to 2022, with some variation in the magnitude of change;

the percentage of births at less than full term rose 14% among

Hispanic mothers compared with increases of 18%–19% among

births to Black and White mothers. It is important to note,

however, that the percentage of births delivered at less than full

term was higher for Black mothers compared with White and

Hispanic mothers throughout the study period. For example, in

2022, this rate was 45.05% for Black mothers compared with

34.99% for White mothers and 38.67% for Hispanic mothers.

Limitations

Gestational age may be misreported in birth certificate data.

Studies conducted from 2009 to 2013 in three vital records

jurisdictions (two states and New York City) found levels of

agreement between hospital records and birth certificate data on

obstetric estimate of gestation within 2 weeks to be high (90.0%

or more) in each state; levels of exact agreement ranged from

moderate (60.0%–74.9%), to substantial (75.0%–89.9%), to

high across the three jurisdictions (16,17).

This report did not take into account changes over the study

period in medical or obstetric indications for delivery, which may

have influenced the observed increase in births occurring at less

than full term. While delivery at 39 completed weeks or later

is considered optimal given reduced morbidity and mortality

compared with delivery at earlier ages, deferring delivery to the

39th week is not recommended if there is a medical or obstetric

indication for earlier delivery (14).

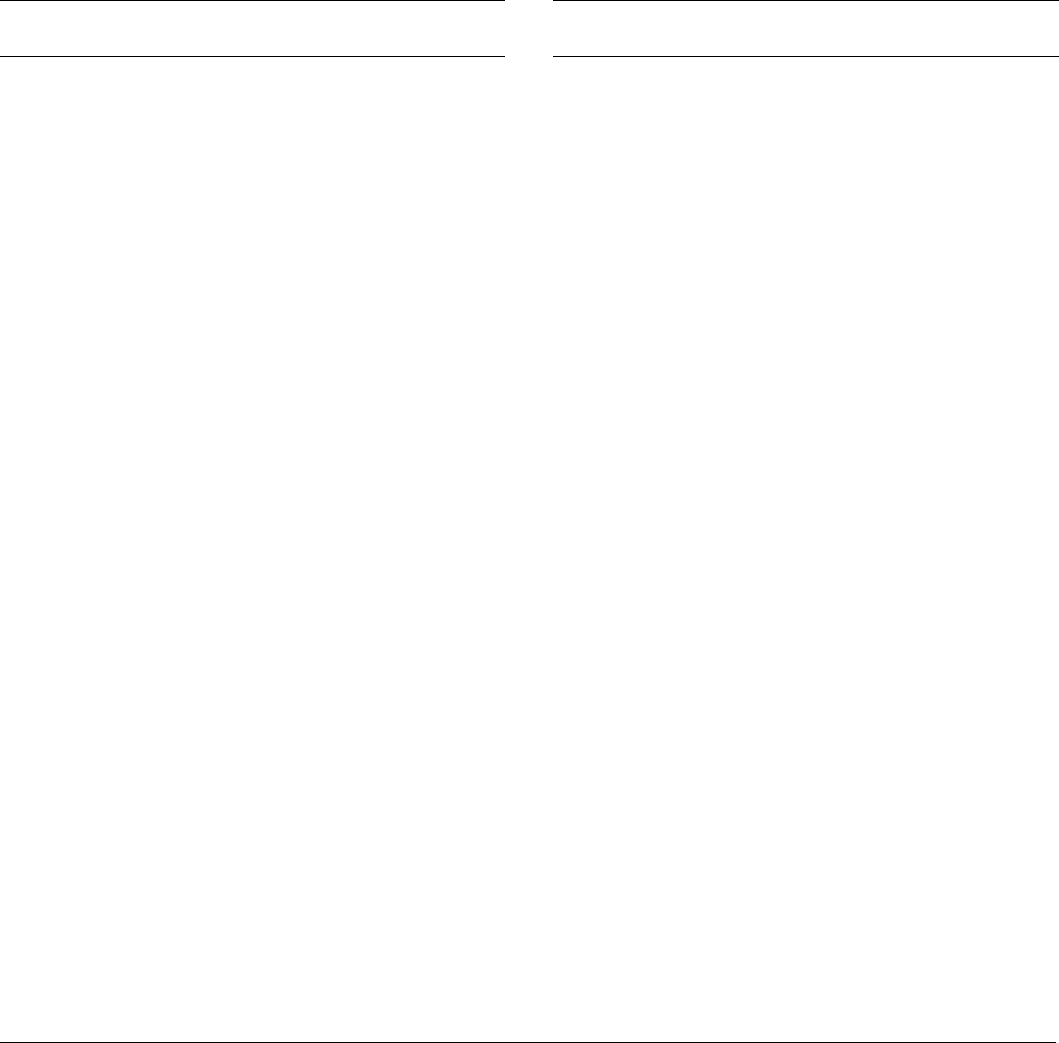

Figure 4. Percentage of singleton births, by single week of gestation: United States, 2014 and 2022

NOTES: Significant changes for each gestational age week (p < 0.05). Singleton births only.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, natality data file.

8.17

11.63

16.13

17.45

38.71

38.84

0

10

20

30

40

37 38 39

40

41

Percent

2014 2022

22.05

18.26

6.77

4.88

National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 73, No. 1, January 31, 2024 7

Summary

Gestational age is a strong predictor of short- and long-term

morbidity and early mortality. Births delivered preterm are at the

greatest risk of adverse outcomes, but risk is also elevated for

early-term compared with full-term births (4,11–14). This report

demonstrates a shift from 2014 through 2022 across gestational

age categories, with the largest changes occurring among early-

term births—particularly those delivered at 37 weeks—and

among late- and post-term births. Similar shifts were observed

across the maternal age and race and Hispanic-origin groups

studied.

References

1. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC,

Mathews TJ. Births: Final data for 2013. National Vital

Statistics Reports; vol 64 no 1. Hyattsville, MD: National

Center for Health Statistics. 2015.

2. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ,

Menacker F, Kirmeyer S, Mathews TJ. Births: Final data

for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 57 no 7.

Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2009.

3. Raju TNK, Higgins RD, Stark AR, Leveno KJ. Optimizing

care and outcome for late-preterm (near-term) infants:

A summary of the workshop sponsored by the National

Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Pediatrics

118(3):1207–14. 2006. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/

peds.2006-0018.

4. Spong CY, Mercer BM, D’Alton M, Kilpatrick S, Blackwell S,

Saade G. Timing of indicated late-preterm and early-term

birth. Obstet Gynecol 118(2 Pt 1):323–33. 2011. DOI:

https://www.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182255999.

5. Osterman MJK, Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Driscoll AK,

Valenzuela CP. Births: Final data for 2021. National Vital

Statistics Reports; vol 72, no 1. Hyattsville, MD: National

Center for Health Statistics. 2023. DOI: https://dx.doi.

org/10.15620/cdc:122047.

6. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United

States, 2022. NCHS Data Brief, no 477. Hyattsville, MD:

National Center for Health Statistics. 2023. DOI: https://

dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:131354.

7. National Center for Health Statistics. User guide to the 2021

natality public use file. 2022. Available from: https://ftp.cdc.

gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/

DVS/natality/UserGuide2021.pdf.

8. National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint Regression Program

(Version 4.9.0.0) [computer software]. 2021.

9. Martin JA, Osterman MJK. Describing the increase in

preterm births in the United States, 2014–2016. NCHS Data

Brief, no 312. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health

Statistics. 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/

products/databriefs/db312.htm.

10. Driscoll AK, Osterman MJK, Hamilton BE, Valenzuela CP,

Martin JA. Quarterly provisional estimates for selected birth

indicators, Quarter 1, 2021–Quarter 2, 2023. National Center

for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Vital

Statistics Rapid Release Program. 2023. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/natality-dashboard.

htm.

11. Clark SL, Miller DD, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, Frye DK,

Meyers JA. Neonatal and maternal outcomes associated

with elective term delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200(2):156.

e1–4. 2009.

12. Tita ATN, Landon MB, Spong CY, Lai Y, Leveno KJ,

Varner MW, et al. Timing of elective repeat cesarean

delivery at term and neonatal outcomes. N Engl J Med

360(2):111–20. 2009. DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.1056/

NEJMoa0803267.

13. Tita ATN, Jablonski KA, Bailit JL, Grobman WA, Wapner RJ,

Reddy UM, et al. Neonatal outcomes of elective early-term

births after demonstrated fetal lung maturity. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 219(3):296.e1–8. 2018. DOI: https://www.doi.

org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.011.

14. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’

Committee on Obstetric Practice, Society for Maternal-

Fetal Medicine. Medically indicated late-preterm and

early-term deliveries: ACOG Committee Opinion, no 831.

Obstet Gynecol 138(1):e35–9. 2021. DOI: https://www.doi.

org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004447.

15. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital statistics online

data portal. 2021 period linked birth–infant death data files.

Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/

VitalStatsOnline.htm.

16. Martin JA, Wilson EC, Osterman MJK, Saadi EW, Sutton SR,

Hamilton BE. Assessing the quality of medical and health

data from the 2003 birth certificate revision: Results from

two states. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 62 no 2.

Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2013.

17. Gregory ECW, Martin JA, Argov EL, Osterman MJK.

Assessing the quality of medical and health data from the

2003 birth certificate revision: Results from New York City.

National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 68 no 8. Hyattsville,

MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2019.

List of Detailed Tables

1. Number and percentage of singleton births, by gestational

age and race and Hispanic origin of mother: United States,

2014–2022. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

2. Distribution of singleton births, by gestational age and age

of mother: United States, 2014–2022 ................. 10

8 National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 73, No. 1, January 31, 2024

Table 1. Number and percentage of singleton births, by gestational age and race and Hispanic origin of mother: United States,

2014–2022

Race and Hispanic origin

and year

Preterm Term

Late and

post-term

(41 or more weeks)

All births

1

(number)

Total

(less than 37 weeks)

Early

(less than 34 weeks)

Late

(34–36 weeks)

Early

(37–38 weeks)

Full

(39–40 weeks)

All races and origins Percent

2022. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,547,741 8.67 2.16 6.51 29.07 57.11 5.15

2021. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,544,292 8.76 2.20 6.56 28.53 57.71 5.01

2020. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,495,915 8.42 2.11 6.30 27.46 58.83 5.29

2019. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,621,616 8.47 2.14 6.32 26.99 58.92 5.62

2018. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,662,203 8.24 2.12 6.12 26.18 59.17 6.41

2017. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,720,586 8.13 2.12 6.02 25.59 59.47 6.81

2016. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,806,807 8.02 2.10 5.92 25.07 59.93 6.97

2015. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,838,382 7.82 2.09 5.73 24.56 60.47 7.15

2014. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,845,046 7.74 2.07 5.67 24.31 60.76 7.20

Percent change

2019–2020. . . . . . . . . . . . … -1 -1 †‡ 2 ‡ -6

2020–2021. . . . . . . . . . . . … 4 4 4 4 -2 -5

2021–2022. . . . . . . . . . . . … -1 -2 -1 2 -1 3

2014–2022. . . . . . . . . . . . … 12 4 15 20 -6 -28

Black, non-Hispanic

2

Percent

2022. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 489,400 12.34 3.97 8.37 32.71 50.90 4.05

2021. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 496,049 12.51 4.04 8.47 32.28 51.35 3.86

2020. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 507,449 12.18 3.94 8.24 31.12 52.58 4.12

2019. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 524,774 12.12 3.99 8.13 30.33 53.08 4.46

2018. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 528,503 11.92 4.00 7.92 29.48 53.50 5.10

2017. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 536,643 11.73 3.94 7.80 28.71 54.09 5.47

2016. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 535,252 11.63 4.01 7.62 28.25 54.56 5.56

2015. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 564,804 11.32 3.96 7.36 27.38 55.50 5.80

2014. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 564,325 11.12 3.88 7.24 26.93 56.08 5.87

Percent change

2019–2020. . . . . . . . . . . . … †§ †-1 1 3 -1 -8

2020–2021. . . . . . . . . . . . … 3 3 3 4 -2 -6

2021–2022. . . . . . . . . . . . … -1 †-2 †-1 1 -1 5

2014–2022. . . . . . . . . . . . … 11 2 16 21 -9 -31

White, non-Hispanic

2

Percent

2022. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,778,229 7.64 1.69 5.96 27.34 59.19 5.83

2021. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,823,277 7.69 1.71 5.98 26.69 59.89 5.73

2020. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,780,710 7.36 1.63 5.72 25.52 61.07 6.05

2019. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,849,136 7.44 1.66 5.78 25.11 61.07 6.38

2018. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,886,312 7.21 1.64 5.57 24.20 61.27 7.33

2017. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,918,410 7.13 1.65 5.48 23.61 61.47 7.80

2016. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,979,051 7.07 1.65 5.43 23.11 61.82 8.00

2015. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,049,655 6.91 1.64 5.27 22.67 62.28 8.14

2014. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,066,324 6.90 1.64 5.26 22.48 62.48 8.14

Percent change

2019–2020. . . . . . . . . . . . … -1 -2 -1 2 †0 -5

2020–2021. . . . . . . . . . . . … 4 5 5 5 -2 -5

2021–2022. . . . . . . . . . . . … -1 †-1 †‡ 2 -1 2

2014–2022. . . . . . . . . . . . … 11 3 13 22 -5 -28

See footnotes at end of table.

National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 73, No. 1, January 31, 2024 9

Table 1. Number and percentage of singleton births, by gestational age and race and Hispanic origin of mother: United States,

2014–2022—Con.

Race and Hispanic origin

and year

Preterm Term

Late and

post-term

(41 or more weeks)

All births

1

(number)

Total

(less than 37 weeks)

Early

(less than 34 weeks)

Late

(34–36 weeks)

Early

(37–38 weeks)

Full

(39–40 weeks)

Hispanic

3

Percent

2022. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 913,437 8.72 2.13 6.59 29.94 56.63 4.71

2021. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 863,477 8.88 2.17 6.71 29.69 57.00 4.42

2020. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 845,176 8.54 2.07 6.47 28.80 57.99 4.68

2019. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 863,731 8.60 2.11 6.48 28.48 57.95 4.97

2018. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 863,610 8.39 2.07 6.32 27.84 58.25 5.53

2017. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 875,663 8.27 2.08 6.19 27.36 58.57 5.80

2016. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 894,619 8.11 2.05 6.06 26.78 59.28 5.82

2015. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 900,251 7.83 2.02 5.82 26.30 59.81 6.06

2014. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 890,808 7.72 2.02 5.70 26.14 59.96 6.17

Percent change

2019–2020. . . . . . . . . . . . … †-1 -2 †‡ 1 †§ -6

2020–2021. . . . . . . . . . . . … 4 5 4 3 -2 -6

2021–2022. . . . . . . . . . . . … 2 -2 -2 1 -1 7

2014–2022. . . . . . . . . . . . … 13 5 16 15 -6 -24

…

Category not applicable.

† Not significant at p < 0.05.

‡ -0.5 to 0.0.

§ 0.5 or less.

1

Excludes unknown gestational age.

2

Race groups are single race (defined as only one race reported on the birth certificate). Race and Hispanic origin are reported separately on birth certificates. Race categories are consistent

with 1997 Office of Management and Budget standards.

3

People of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, natality data file.

10 National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 73, No. 1, January 31, 2024

Gestational age

and year Total

Younger

than 20 20–29 30–39 40 or older

Preterm Percent

2022. . . . . . . . . 8.67 9.66 8.23 8.69 12.52

2021. . . . . . . . . 8.76 9.72 8.33 8.77 12.79

2020. . . . . . . . . 8.42 9.33 8.05 8.42 12.12

2019. . . . . . . . . 8.47 9.37 8.13 8.46 12.10

2018. . . . . . . . . 8.24 9.37 7.92 8.21 11.72

2017. . . . . . . . . 8.13 9.24 7.83 8.09 11.70

2016. . . . . . . . . 8.02 9.36 7.72 7.96 11.53

2015. . . . . . . . . 7.82 8.95 7.55 7.76 11.03

2014. . . . . . . . . 7.74 8.85 7.49 7.65 10.82

Percent change

2019–2020. . . . -1 †‡ -1 †‡ †§

2020–2021. . . . 4 4 3 4 6

2021–2022. . . . -1 †-1 -1 -1 -2

2014–2022. . . . 12 9 10 14 16

Early preterm Percent

2022. . . . . . . . . 2.16 2.71 2.04 2.14 3.23

2021. . . . . . . . . 2.20 2.69 2.08 2.18 3.34

2020. . . . . . . . . 2.11 2.63 2.02 2.09 3.07

2019. . . . . . . . . 2.14 2.65 2.03 2.12 3.28

2018. . . . . . . . . 2.12 2.65 2.03 2.09 3.10

2017. . . . . . . . . 2.12 2.69 2.01 2.09 3.21

2016. . . . . . . . . 2.10 2.71 2.00 2.06 3.21

2015. . . . . . . . . 2.09 2.59 2.01 2.05 3.13

2014. . . . . . . . . 2.07 2.57 1.98 2.02 3.14

Percent change

2019–2020. . . . -1 †-1 †‡ -1 -6

2020–2021. . . . 4 †2 3 4 9

2021–2022. . . . -2 †1 -2 -2 †-3

2014–2022. . . . 4 5 3 6 †3

Late preterm Percent

2022. . . . . . . . . 6.51 6.95 6.19 6.54 9.28

2021. . . . . . . . . 6.56 7.03 6.25 6.59 9.44

2020. . . . . . . . . 6.30 6.70 6.04 6.33 9.04

2019. . . . . . . . . 6.32 6.71 6.09 6.34 8.82

2018. . . . . . . . . 6.12 6.71 5.89 6.13 8.61

2017. . . . . . . . . 6.02 6.56 5.82 6.01 8.49

2016. . . . . . . . . 5.92 6.65 5.72 5.90 8.32

2015. . . . . . . . . 5.73 6.36 5.54 5.71 7.90

2014. . . . . . . . . 5.67 6.28 5.51 5.63

7.68

Percent change

2019–2020. . . . †‡ †‡ -1 †‡ 2

2020–2021. . . . 4 5 3 4 4

2021–2022. . . . -1 †-1 -1 -1 †-2

2014–2022. . . . 15 11 12 16 21

Table 2. Distribution of singleton births, by gestational age and age of mother: United States, 2014–2022

† Not significant at p < 0.05.

‡ -0.5 to 0.0.

§ 0.5 or less.

NOTES: Singleton births only. Preterm is less than 37 weeks of gestation, early term is 37–38 weeks, full term is 39–40 weeks, and late and post-term is 41 weeks and later.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, natality data file.

Gestational age

and year Total

Younger

than 20 20–29 30–39 40 or older

Early term Percent

2022. . . . . . . . . . . 29.07 29.25 28.68 29.06 33.71

2021. . . . . . . . . . . 28.53 28.57 28.28 28.39 33.30

2020. . . . . . . . . . . 27.46 27.45 27.20 27.34 32.52

2019. . . . . . . . . . . 26.99 27.19 26.76 26.86 31.82

2018. . . . . . . . . . . 26.18 26.43 25.99 25.99 31.00

2017. . . . . . . . . . . 25.59 26.01 25.39 25.45 29.90

2016. . . . . . . . . . . 25.07 25.37 24.91 24.91 29.30

2015. . . . . . . . . . . 24.56 25.16 24.39 24.40 28.39

2014. . . . . . . . . . . 24.31 24.87 24.14 24.19 27.68

Percent change

2019–2020. . . . . . 2 †1 2 2 2

2020–2021. . . . . . 4 4 4 4 2

2021–2022. . . . . . 2 2 1 2 1

2014–2022. . . . . . 20 18 19 20 22

Full term Percent

2022. . . . . . . . . . . 57.11 55.89 57.72 57.09 51.47

2021. . . . . . . . . . . 57.71 56.68 58.25 57.76 51.48

2020. . . . . . . . . . . 58.83 57.62 59.37 58.86 52.87

2019. . . . . . . . . . . 58.92 57.44 59.40 58.99 53.26

2018. . . . . . . . . . . 59.17 57.22 59.56 59.34 53.95

2017. . . . . . . . . . . 59.47 57.49 59.83 59.65 54.72

2016. . . . . . . . . . . 59.93 57.85 60.26 60.17 55.01

2015. . . . . . . . . . . 60.47 58.32 60.76 60.75 56.07

2014. . . . . . . . . . . 60.76 58.57 61.01 61.08 56.67

Percent change

2019–2020. . . . . . ‡ †§ †‡ ‡ -1

2020–2021. . . . . . -2 -2 -2 -2 -3

2021–2022. . . . . . -1 -1 -1 -1 †‡

2014–2022. . . . . . -6 -5 -5 -7 -9

Late and post-term Percent

2022. . . . . . . . . . . 5.15 5.21 5.37 5.17 2.31

2021. . . . . . . . . . . 5.01 5.03 5.14 5.08 2.44

2020. . . . . . . . . . . 5.29 5.60 5.38 5.39 2.49

2019. . . . . . . . . . . 5.62 6.00 5.72 5.69 2.82

2018. . . . . . . . . . . 6.41 6.99 6.53 6.45 3.34

2017. . . . . . . . . . . 6.81 7.26 6.96 6.81 3.68

2016. . . . . . . . . . . 6.97 7.41 7.11 6.96 4.15

2015. . . . . . . . . . . 7.15 7.57 7.31 7.09 4.52

2014. . . . . . . . . . . 7.20 7.71 7.36 7.08 4.82

Percent change

2019–2020. . . . . . -6 -7

-6 -5 -12

2020–2021. . . . . . -5 -10 -4 -6 †-2

2021–2022. . . . . . 3 4 4 2 -5

2014–2022. . . . . . -28 -32 -27 -27 -52

FIRST CLASS MAIL

POSTAGE & FEES PAID

CDC/NCHS

PERMIT NO. G-284

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF

HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Health Statistics

3311 Toledo Road, Room 4551

Hyattsville, MD 20782–2064

OFFICIAL BUSINESS

PENALTY FOR PRIVATE USE, $300

National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 73, No. 1, January 31, 2024

For more NCHS NVSRs, visit:

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/nvsr.htm.

For e-mail updates on NCHS publication releases, subscribe online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/email-updates.htm.

For questions or general information about NCHS: Tel: 1–800–CDC–INFO (1–800–232–4636) • TTY: 1–888–232–6348

Internet: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs • Online request form: https://www.cdc.gov/info • CS345982

Suggested citation

Martin JA, Osterman MJK. Shifts in the

distribution of births by gestational age: United

States, 2014–2022. National Vital Statistics

Reports; vol 73 no 1. Hyattsville, MD: National

Center for Health Statistics. 2024. DOI: https://

dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:135610.

Copyright information

All material appearing in this report is in

the public domain and may be reproduced

or copied without permission; citation as to

source, however, is appreciated.

National Center for Health Statistics

Brian C. Moyer, Ph.D., Director

Amy M. Branum, Ph.D., Associate Director for

Science

Division of Vital Statistics

Paul D. Sutton, Ph.D., Acting Director

Andrés A. Berruti, Ph.D., M.A., Associate

Director for Science

Contents

Abstract .......................................................1

Introduction ....................................................1

Methods .......................................................1

Results ........................................................2

Preterm births (less than 37 weeks of gestation) ......................2

Early-term births (37–38 weeks of gestation). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Full-term births (39–40 weeks of gestation) ..........................4

Late- and post-term births (41–42 and later weeks of gestation) ..........5

Early-, full-, and late-term births by single week of gestation .............5

Discussion .....................................................5

Limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

References .....................................................7

List of Detailed Tables ............................................7

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared in the Division of Vital Statistics under the general

direction of Acting Director Paul D. Sutton and Robert N. Anderson, Chief,

Statistical Analysis and Surveillance Branch. The authors would like to thank

Acting Deputy Director Isabelle Horon for her helpful comments.