Traffic Calming

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

TRAFFIC CALMING

L E S S O N 11L E S S O N 11

L E S S O N 11L E S S O N 11

L E S S O N 11

FHWA

11 - 1

11.2 Traffic-Calming

Objectives

The most fundamental traffic-calming goal is to

reduce the speed of vehicular movement. With

reduction of speed, the following objectives can be

realized:

1. Improved “feel” of the street.

This objective calls for increased community

involvement in and “ownership” of the street. If

people feel more comfortable on the street, they

are more likely to walk or bicycle there and to

11.1 Purpose

Traffic calming is a traffic management approach that

evolved in Europe and is now being implemented in

many U.S. cities. The following definition is quoted

from An Illustrated Guide to Traffic Calming by

Hass Klau (1990):

“Traffic calming is a term that has emerged in Europe

to describe a full range of methods to slow cars, but

not necessarily ban them, as they move through

commercial and residential neighborhoods. The

benefit for pedestrians and bicyclists is that cars now

drive at speeds that are safer and more compatible to

walking and bicycling. There

is, in fact, a kind of equilibrium

among all of the uses of a

street, so no one mode can

dominate at the expense of

another.”

This chapter explores the

principle of traffic calming and

provides a variety of studies,

design details, and photo-

graphs of areas where traffic

calming has been effectively

used in the United States and

in Europe. Along with the

advantages of traffic calming,

the text describes mistakes

that practitioners have

sometimes made in implement-

ing traffic-calming techniques.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 2

TRAFFIC CALMING

engage in other street-

oriented activities with their

neighbors. A key aspect of

achieving this objective is

reducing the perceived

threat of danger from motor

traffic.

2. Enhanced aesthetic values

and a sense of nature.

Several traffic-calming

techniques, such as street

landscaping, pedestrian

amenities, and reclamation

of roadway areas can serve

as community open space.

Not only do these tech-

niques make the neighborhood more attractive,

but they also break up long, uninterrupted street

vistas conducive to speeding and convey the

message that “this is a pedestrian place.”

3. Reduced crime.

It’s harder to make a speedy getaway if a fleeing

felon has to deal with speed humps, woonerfs,

and traffic circles. It’s harder to get away

without being spotted if there are “eyes on the

street” – if the street is a positive, community

focus.

4. Equitable balance among transportation modes.

With reduced motorist speeds, safety is im-

proved. Pedestrians and bicyclists have more

time to detect and avoid motor vehicles. Traffic

Traffic-calming devices are used to break up long

uninterrupted street vistas that encourage

speeding.

calming sends the message that

“motor vehicles don’t exclu-

sively OWN the roadway” –

that other modes have equal

rights. Studies that evaluate

traffic-calming improvements

show increased levels of

walking, bicycling, and transit

use following installation.

5. Increased safety/de-

creased severity of injury in

traffic crashes. With reduced

speeds comes a significant

reduction in the number and

severity of crashes involving

motor vehicles. Traffic-calming

facility evaluations uniformly show fewer

crashes, fewer fatalities, and less severe injuries.

6. Improved air quality and noise levels.

Slower moving vehicles make less noise and,

generally, emit fewer pollutants.

7. Decreased fuel consumption.

With more trips made by walking, bicycling, and

transit, and with slower traffic speeds, fuel

consumption reductions of 10 to 12 percent have

been reported.

8. Continued accommodation of motor vehicle

traffic.

An important objective is the continued accom-

modation of motor vehicle traffic. Although

traffic calming shifts the balance among travel

modes, this shift should not result in

severely restricted traffic volumes or

in shifting traffic problems from the

traffic-calmed area to other streets.

11.3 Traffic-Calming

Issues

When any new traffic management

approach is introduced, issues,

concerns, and questions are bound

to arise. Design decisions related to

traffic can have far-reaching conse-

quences. Lives, economic well-being,

and urban livability are directly

affected.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 3

TRAFFIC CALMING

Professional engineers, planners,

government, and the public all are

aware of and sensitive to proposals

for changes in the traffic environ-

ment. Roadway congestion, air

quality, traffic safety, street crimes,

and the high cost of new improve-

ments are among the most-widely

debated issues in America today.

New design ideas are, and should be,

subjected to rigorous testing and

evaluation before being accepted as

part of the standard engineering and

transportation planning tool kit.

Traffic calming is not a panacea for

urban transportation woes, but it can

have significant benefits in many

situations.

In considering the application of traffic-calming

techniques, what specific issues are likely to arise?

The discussion on the following pages focuses on

traffic-calming issues. (Note: Studies and statistics

referenced are cited in FHWA Case Study Nos. 19

and 20, National Bicycling and Walking Study.)

1. Traffic safety.

The Issue: Encouraging people to walk, play, and

bicycle in and next to the streets is just asking for

trouble. They will have a false sense of security and

accidents will increase. They will develop bad habits

that may increase their when they leave the

neighborhood.

Comment: Traffic-calming measures have been

implemented in many European cities. In the

Netherlands and Germany, extensive research has

been conducted to evaluate the safety and impact of

traffic-calming techniques and devices.

2. Impact on traffic volumes, distribution, and

operations.

The Issue: Traffic calming will never work on

anything except very low-volume residential streets.

It will substantially reduce the amount of traffic that a

street can handle efficiently and this is counterpro-

ductive. We need to move vehicles, not restrict them.

Furthermore, if we slow traffic on one street, the

traffic will simply be diverted to another street. The

net result will be increased congestion and more

problems overall.

Comment: A 5-year German Federal Government

evaluation of traffic calming and follow-up research

found:

• Little change in overall traffic volumes.

• Reduction in average vehicle speeds by almost

50 percent.

• Average increase in motorist trip time of only 33

seconds.

3. Lack of proven design standards.

The Issue: There are no uniform, accepted, and

legally defensible standards to follow. If we want to

try traffic calming, where can we get specific informa-

tion about design?

Comment: Many U.S. cities are now developing and

testing design guidelines for traffic-calming improve-

ments. Although uniform, national standards have

yet to evolve, valuable experience is being gained.

The list of references at the end of this lesson

provides a starting point for further exploration of

specific design approaches.

4. Liability.

The Issue: These traffic-calming ideas may be

accepted in Europe, but they haven’t really been tried

here. Are we opening the door to all kinds of legal

problems if somebody crashes on a traffic circle or a

speed table and sues us?

Comment: When considering the use of any new

design approach, concerns about liability can be

Traffic calming can be termed as engineering and other physical measures designed

to control traffic speeds and encourage driving behavior appropriate to the

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 4

TRAFFIC CALMING

addressed somewhat through performance of “due

diligence” on the part of the engineer, planner, or

other professionals involved in the design. Research

into the experiences of other U.S. cities, European

standards, and evaluation studies should be thor-

ough and followed up with a first-hand look if

possible. Construction of a pilot project or other

testing of proposed designs can benefit, as can on-

going and systematic evaluation of the improvements

once installed.

5. Emergency and service vehicle access.

The Issue: Construction of speed bumps, neck-

downs, medians, and traffic circles will increase

response times for emergency vehicles and may

restrict access for garbage trucks, delivery vans, and

other large vehicles.

Comment: Studies in Berkley and Palo Alto, CA,

show that traffic management measures (e.g., traffic

diverters, bicycle boulevards) have not impaired

police or fire emergency response times.

• The Seattle Engineering Department works

closely with its Fire Department to design and

field-test traffic circles on a site-specific basis to

ensure good emergency access.

6. Impacts on bicycling.

The Issue: Pavement texturing, speed tables, wider

sidewalks, “bulb-outs” at corners and similar

improvements may make things better for pedestri-

ans, but may have a negative impact on bicycling.

Emergency vehicle access should always be considered when incorporating traffic-calming

measures.

Comment: A 5-year German Federal

Government evaluation of traffic

calming and follow-up research

found doubling of bicycle use over a

4-year period.

• Implementation of traffic manage-

ment strategies in the downtown

area of the Dutch City of

Groningen contributed to a

substantial increase in bicycling

and walking. Bicycle use is now

well over 50 percent of all trips.

• Studies of traffic-calming areas in

Japan show increases in both

bicycle and pedestrian traffic

volumes along most routes.

(Note: Cyclists and Traffic Calming, a Technical

Note publication of the Cyclists Touring Club (see

references, end of lesson), includes extensive

information on adapting traffic-calming techniques

for bicycling.

11.4 Traffic-Calming

Devices

Traffic calming has many potential applications,

especially in residential neighborhoods and small

commercial centers. Traffic-calming devices can be

grouped within the following general categories:

• Bumps, humps, and other raised

pavement areas.

• Reducing street area where motor traffic

is given priority.

• Street closures.

• Traffic diversion.

• Surface texture and visual devices.

• Parking treatments.

Frequently, a combination of traffic-calming devices

is used. Examples of such combinations will be

discussed briefly, including:

• The woonerf.

• Entry treatments across intersections.

• Shared surfaces.

• Bicycle boulevards.

• Slow streets.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 5

TRAFFIC CALMING

Speed Humps

A speed hump (or “road hump”)

is a raised area in the roadway

pavement surface extending

transversely across the roadway.

Speed humps normally have a

minimum height of 3 to 4 inches

and a travel length of approxi-

mately 12 feet, although these

dimensions may vary. In some

cases, the speed hump may raise

the roadway surface to the height

of the adjacent curb for a short

distance.

The humps can be round or flat-

topped. The flat-topped

configuration is sometimes called

a “speed table.” Humps can

either extend the full width of the road, curb-to-curb,

or be cut back at the sides to allow bicycles to pass

and facilitate drainage.

Design Considerations:

• If mid-block pedestrian crossings exist or are

planned, they can be coordinated with speed

hump installation since vehicle speeds will be

lowest at the hump to negotiate ramps or curbs

between the sidewalk and the street.

• The hump must be visible at night.

• Speed humps should be located to avoid conflict

with underground utility access to boxes, vaults,

and sewers.

Speed humps slow traffic speeds on residential streets.

Speed bumps can be combined with curb extensions

and a winding street alignment. Signing and

pavement markings should clearly identify the bump.

• Channelization changes.

• Traffic calming on a major

road.

• Modified intersection

design.

1. Bumps, humps, and other

raised pavement areas.

This category includes all

traffic-calming devices raised

above pavement level. Drivers

must slow down when they

cross these devises or suffer an

uncomfortable KER-BUMP or

(KER-BUMP-KER-BUMP),

running the risk of spilled

coffee and a severe jolt to their

tailbones. Although people

often gripe about the inconvenience of having to

slow down for these devices, they don’t have much

choice. Their effectiveness at slowing traffic cannot

be disputed. They are sometimes referred to as

“Silent Policemen.”

Included in this category are:

• Speed bumps.

• Speed humps.

• Raised crosswalks.

• Raised intersections.

The following are brief descriptions of each, with

definitions, comments, and examples:

Speed Bumps

A speed bump is a raised area in the

roadway pavement surface extending

transversely across the travel way,

generally with a height of 3 to 6 inches

and a length of 1 to 3 feet.

Design Considerations:

• Most effective if used in a series at

300- to 500- foot spacing.

• Typically used on private property

for speed control – parking lots,

apartment complexes, private

streets, and driveways.

• Speed bumps are not conducive to

bicycle travel, so they should be

used carefully.

• Speed humps should not be constructed at

driveway locations.

• Speed humps may be constructed on streets

without curbs, but steps should be taken to

prevent circumnavigation around the humps in

these situations.

• Adequate signing and marking of each speed

hump is essential to warn roadway users of the

hump’s presence and guide their subsequent

movements.

• Speed humps should not be installed in street

sections where transit vehicles must transition

between the travel lane and curbside stop. To

the extent possible, speed humps should be

located to ensure that transit vehicles can

traverse the hump perpendicularly.

• A single hump acts as only a point speed

control. To reduce speeds along an extended

section of street, a series of humps is usually

needed. Typically, speed humps are spaced at

between 300 and 600 feet apart.

Example:

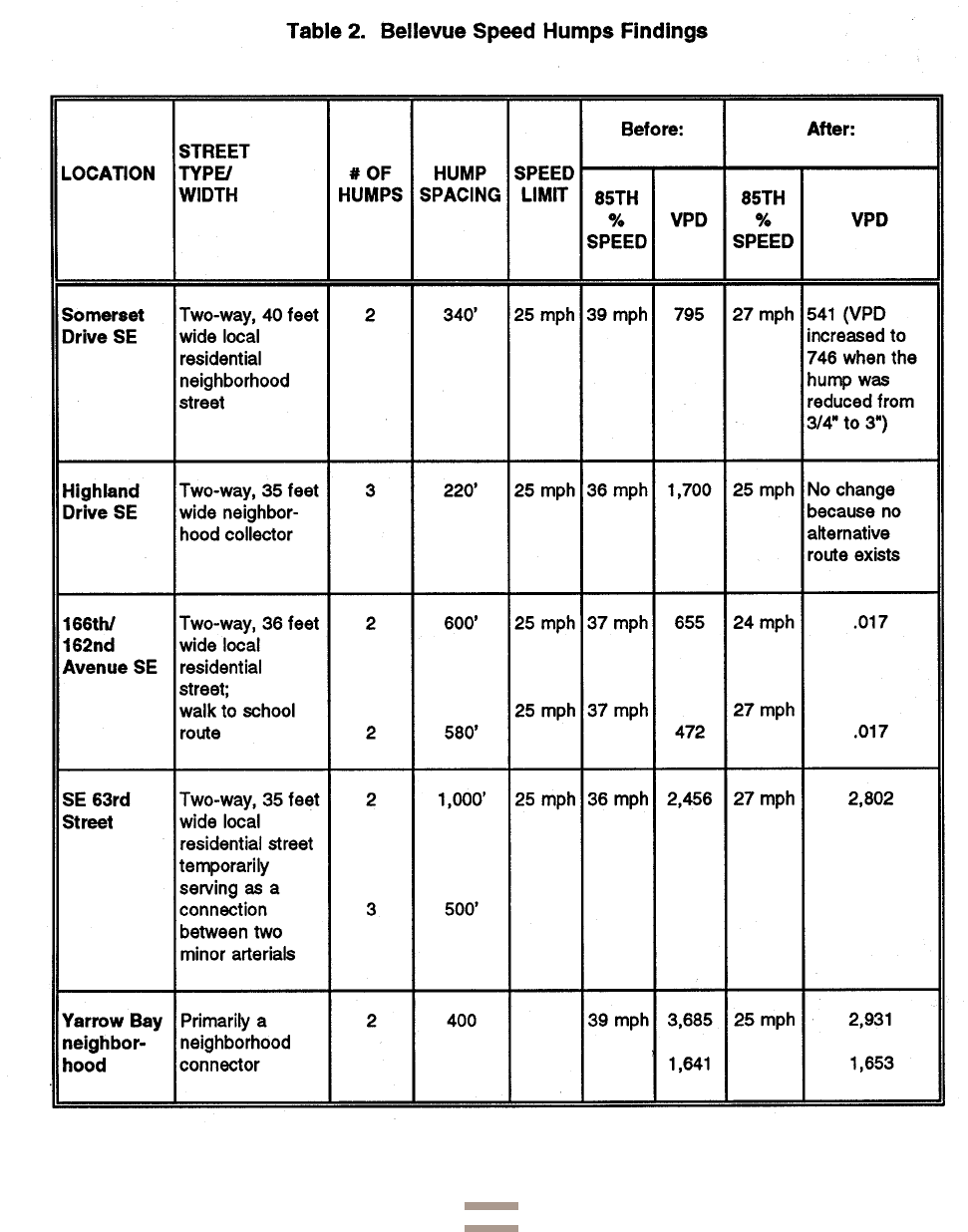

Bellevue, Washington has installed speed humps in

residential neighborhoods (labeled as speed

“bumps” below, although broader than the typical

speed bump). The City uses a 12-foot-wide hump, 3

inches high at the center. The design allows for little

or no discomfort at speeds of 15 to 25 mph, but will

cause discomfort at higher speeds. The humps are

marked clearly, distinguishing them from crosswalks.

White reflectors enhance nighttime visibility.

Bellevue found that the speed humps reduced traffic

speeds and volumes. The humps, in general,

received strong public support, and residents

favored their permanent installation.

The following concerns were raised regarding the

speed hump installation:

• Concern about restricted access and increased

response time for emergency vehicles. The

Bellevue Fire Department asked that the humps

be installed on primary emergency access routes.

• Concern about aesthetics of signing and

markings at the traffic humps. Residents raising

the concerns, however, felt that the speed

reductions compensated for the appearance of

the humps.

• Concern about the effectiveness of the humps in

reducing motor vehicle speeds along the length

of a street, not at just two or three points. The

distance between speed humps was found to

have an impact on traffic speeds. The City

found that maximum spacing should be approxi-

mately 500 feet.

The Bellevue Department of Public

Works concluded that speed humps

were effective speed-control measures

on residential streets and recommended

their use be continued. The table on the

following page summarizes “before” and

“after” data related to the Bellevue

speed humps:

Raised Crosswalks

Raised crosswalks are essentially broad,

flat-topped speed humps that coincide

with pedestrian crosswalks at street

intersections. The crosswalks are raised

above the level of the roadway to slow

traffic, enhance crosswalk visibility, and

make the crossing easier for pedestrians

who may have difficulty stepping up

and down curbs.

Raised crosswalks can both slow motor traffic and give pedestrians a continuous-

level surface at the crossing. Changes in texture and color help define the edges

of the crossing.

11 - 6

FHWA

GRADUATE COURSE BOOK ON

BICYCLE AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

TRAFFIC CALMING

11 - 7

FHWA

GRADUATE COURSE BOOK ON

BICYCLE AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

TRAFFIC CALMING

Source: FHWA Case Study No. 19.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 8

TRAFFIC CALMING

Design Considerations:

• Can be constructed of brick, concrete block,

colored asphalt or cement, with ramps striped for

better visibility.

• Raised crosswalks are applicable:

(1) On roadways with vehicular speeds perceived

as being incompatible with the adjacent

residential land uses.

(2) Where there is a significant number of pedes-

trian crossings.

(3) In conjunction with other traffic-calming

devices, particularly entry treatments.

(4) On two-lane or fewer residential streets

classified as either “local streets” or neighbor-

hood collector streets.”

(5) On roadways with 85

th

percentile speeds less

than 45 mph.

Intersection Humps/Raised Intersections

Intersection humps raise the roadway at the intersec-

tion, forming a type of “plateau” across the

intersection, with a ramp on each approach. The

plateau is at curb level and can be enhanced through

the use of distinctive surfacing such as pavement

coloring, brickwork, or other pavements. In some

cases, the distinction between roadway and sidewalk

surfaces is blurred. If this is done, physical obstruc-

tions such as bollards or planters should be

considered, restricting the area to which motor

vehicles have access.

Design Considerations:

• Ramps should not exceed a

maximum gradient of 16 percent.

• Raised and/or textured surfaces can

be used to alert drivers to the need

for particular care.

• Distinctive surfacing helps

reinforce the concept of a “calmed”

area and thus plays a part in

reducing vehicle speeds.

• Distinctive surfacing materials

should be skid-resistant, particu-

larly on inclines.

• Ramps should be clearly marked to enable

bicyclists to identify and anticipate them,

particularly under conditions of poor visibility.

• Care must be taken so the visually impaired have

adequate cues to identify the roadway’s location

(e.g., tactile strips). Color contrasts will aid

those who are partially sighted.

2. Reducing street area where motor traffic is given

priority.

This category of traffic-calming techniques includes

all those that reduce the area of the street designated

exclusively for motor vehicle travel. “Reclaimed”

space is typically used for landscaping, pedestrian

amenities, and parking.

Discussed here are:

• Slow points.

• Medians.

• Curb extensions.

• Corner radius treatment.

• Narrow traffic lanes.

Slow Points (neck-downs, traffic throttles, pinch

points)

Slow points narrow a two-way road over a short

distance, forcing motorists to slow and, in some

cases, to merge into a single lane. Sometimes these

are used in conjunction with a speed table and

coincident with a pedestrian crossing. The following

are advantages and disadvantages of both one-lane

and two-lane slow points:

ONE-LANE SLOW POINT TWO-LANE SLOW POINT

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 9

TRAFFIC CALMING

(1) One-lane slow point.

One-lane slow points restrict traffic flow to one lane.

This lane must accommodate motor traffic in both

travel directions. Passage through the slow point

can be either straight through or angled.

Advantages:

• Vehicle speed reduced.

• Most effective when used in a series.

• Imposes minimal inconvenience to local traffic.

• Pedestrians have a reduced crossing distance,

greater safety.

Disadvantages:

• Reduced sight distances if landscaping is not

low and trimmed.

• Contrary to driver expectations of unobstructed

flow.

• Can be hazardous for drivers and bicyclists if not

designed and maintained properly.

• Opposing drivers arriving simultaneously can

create confrontation.

(2) Two-lane slow point.

Two-lane slow points narrow the roadway while

providing one travel lane in each direction.

Advantages:

• Only a minor inconvenience to drivers.

• Regulates parking and protects parked vehicles

as the narrowing can help stop illegal parking.

• Pedestrian crossing distances reduced.

• Space for landscaping provided.

Disadvantages:

• Not very effective in slowing

vehicles or diverting through

traffic.

• Only partially effective as a

visual obstruction.

Design Considerations:

• Where slow points have been

used in isolation as speed

control measures, bicyclists

have felt squeezed as motorists

attempt to overtake them at the

narrowing. Not all bicyclists

have the confidence to position

themselves in the middle of the

road to prevent overtaking on the approach to

and passage through the narrow area.

• To reduce the risk of bicyclists’ being squeezed,

slow points should generally be used in con-

junction with other speed control devices such

as speed tables at the narrowing. Slower moving

drivers will be more inclined to allow bicyclists

through before trying to pass. Where bicycle

flows are high, consideration should be given to

a separate right-of-way for bicyclists past the

narrow area.

• A textured surface such as brick or pavers may

be used to emphasize pedestrian crossing

movement. Substituting this for the normal

roadway surface material may also help to

impress upon motorists that lower speeds are

intended.

• Such measures should not confuse pedestrians

with respect to the boundary of the roadway

area over which due care should still be taken.

In particular, where a road is raised to the level of

the adjacent sidewalk, this can cause problems

for those with poor sight. However, a tactile

strip may help blind people in distinguishing

between the roadway and the sidewalk; similarly,

a color variation will aid those who are partially

sighted.

• Slow points can be used to discourage use of

the street by large vehicles. They can, however,

be barriers to fire trucks and other emergency

This traffic-calming measure uses a landscaped median to narrow the travel lanes.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 10

TRAFFIC CALMING

This median provides a diagonal waiting area

for bicyclists, including a railing to hold onto.

vehicles. Some designs

permit access by emer-

gency vehicles by means

of lockable posts or

ramped islands.

• Slow points can enhance

the appearance of the

street. For example,

landscaped islands can be

installed, intruding into

the roadway to form a

narrow “gate” through

which drivers must pass.

Landscaping enhances the

neighborhood’s sense of

nature and provides a

visual break in views along

the street.

• Slow points are generally only sanctioned

where traffic flows are less then 4,000 to 5,000

vehicles per day. Above this level, considerable

delays will occur during peak periods.

• Clear signing should indicate traffic flow

priorities.

Slow Point Examples:

Medians

Medians are islands located along the roadway

centerline, separating opposing directions of traffic

movement. They can be either raised or flush with

the level of the roadway surface. They can be

expressed as painted pavement markings, raised

concrete platforms, landscaped areas, or any of a

variety of other design forms. Medians can provide

special facilities to accommodate pedestrians and

bicyclists, especially at crossings of major road-

ways.

Design Considerations:

• Medians are most valuable on major, multi-lane

roads that present safety problems for bicyclists

and pedestrians wishing to cross. The minimum

central refuge width for safe use by those with

wheelchairs, bicycles, baby buggies, etc. is 1.6

meters (2 meters is desirable).

• Where medians are used as pedestrian and

bicyclist refuges, internally illuminated bollards

are suggested on the medians to facilitate quick

and easy identification.

• Used in isolation, roadway medians

do not have a significant impact in

reducing vehicle speeds. For the

purpose of slowing traffic, medians

are generally used in conjunction

with other devices, such as curb

extensions or roadway lane

narrowing.

Several caveats apply:

• To achieve meaningful speed

reductions, the travel lane width

reduction must be substantial and

visually obvious. The slowing,

however, is temporary; as soon as

the roadway widens again, traffic

resumes its normal speed.

• Bicyclists have been put at risk of being

squeezed where insufficient room has been left

between a central median and the adjacent curb.

Experience shows that most drivers are unlikely

to hold back in such instances to let bicyclists

go through first. This threat is particularly

serious on roads with high proportions of heavy

vehicles.

• The contradiction between the need to reduce

the roadway width sufficiently to lower motor-

ist speeds, while at the same time leaving

enough room for bicyclists to ride safely, must

be addressed. This may be achieved by reducing

the roadway width to the minimum necessary

for a bicyclist and a motorist to pass safely

(i.e., 3.5 meters).

There are three suggestions:

• Introducing color or texture changes to the road

surface material around the refuge area reminds

motorist that a speed reduction is intended.

• White striping gives a visual impression that

vehicles are confined to a narrower roadway

than that created by the physical obstruction —

adjacent areas exist that vehicles can run over,

but these are not generally apparent to ap-

proaching drivers.

• In some cases, provide an alternate, cut-through

route for the bicyclists.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 11

TRAFFIC CALMING

A 7-foot radius allows for a slow and safe turn. As the radius increases, so does the speed

of the vehicle.

Curb Extensions

The sidewalk and/or landscaped

area on one or both sides of the

road is extended to reduce the

roadway to a single lane or

minimum-width double lane. By

reducing crossing distances,

sidewalk widening is used to

facilitate easier and safer

pedestrian movement.

Reducing roadway width results

in vehicle speed reductions.

When curb extensions are used

at intersections, the resultant

tightened radii ensure that

vehicles negotiating the

intersection do so at slow

speeds.

Design Considerations:

• Can be installed either at intersections or mid-

block.

• May be used in conjunction with other traffic-

calming devices.

• Curb extensions are limited only to the degree

that they extend into the travelway. Curb

extensions cannot impede or restrict the opera-

tion of the roadway.

• Successful bicycle facilities need a clear separa-

tion from sidewalk and street pavement, with

adequate distances from parked cars to avoid

opening doors. Cross-traffic should be slowed

to allow bicyclists better continuity and safety.

• Narrowing certain streets can, at the same time,

create safer bicycle facilities, but care should be

taken that bicyclists are not squeezed by

overtaking vehicles where the road narrows.

Encouraging motorists to let the bicyclists

through first by using complementary traffic-

calming techniques such as speed tables and

cautionary signing or leaving sufficient room for

both to pass safely at the narrowing would be

appropriate measures.

• If it is expected that a motorist should be able to

pass a bicyclist, the minimum desirable width is

3.5 meters.

• Curb extensions can be employed to facilitate

bicycle movement where a segregated multi-use

trail crosses a busy street.

Corner Radius Treatment

Corner radii of intersection curbs are reduced, forcing

turning vehicles to slow down. Efforts to accommo-

date trucks and other large vehicles have historically

led to increased corner radii at intersections.

The following results have been observed:

• Large vehicles (trucks, vans, etc.) turn the

corners easily.

• Other vehicles turn faster than with a reduced

radius corner.

• Pedestrian crossing distances are increased by

up to 4 feet, depending on the radius.

• Pedestrian safety is decreased, due to higher

speeds.

• The sharper turns that result from the reduced

radii require motorists to reduce speed, increas-

ing the time available to detect and take

appropriate actions related to pedestrians at the

crossing.

Advantage:

• Can result in increased safety for pedestrians by

reducing crossing distances and slowing the

speed of turning vehicles.

Disadvantages:

• May result in wide swings in turning movements

of large vehicles.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 12

TRAFFIC CALMING

• May affect response times for emergency

vehicles.

Design Consideration:

• To slow traffic, a corner radius of approximately 7

feet is recommended.

Narrow Traffic Lanes

Especially in residential areas, wide streets may not

be necessary or desirable. Wide traffic lanes

encourage faster motor vehicle speeds. Consider-

ation should be given to the review of cross-sections

for all street classifications to determine whether

roadway lane widths can be reduced (within

AASHTO guidelines) so more area can be dedicated

to bicycle and pedestrian use and associated traffic-

calming facilities.

Advantages:

• Additional area for landscaping, and pedestrian

facilities.

• Reduced vehicle speeds and increased safety.

Disadvantage:

• On-street parking may be restricted.

Design Consideration:

• Cross-section approaching the reduced-

width street should also be slowed.

Example: City of Portland, Skinny Street Program

The City of Portland requires most newly constructed

residential streets to be 20 or 26 feet wide, depending

The design of street closures should provide specific parking areas to discourage

obstruction of bicycle and pedestrian traffic.

on neighborhood on-street parking

needs. In the past, residential

streets were required to be as wide

as 32 feet. To achieve a variety of

benefits, the City reduced residential

street widths. The City’s Fire Bureau

participated in the development of

this standard to ensure access for

emergency vehicles.

3. Street closures.

Three types of street closures are

described in the following discus-

sion:

• Complete street closures.

• Partial street closures.

• Driveway links.

(Caution: Street closures must be considered in an

area-wide context or traffic problems may simply shift

to another nearby street).

Complete Street Closures

Street closures, generally on residential streets, can

prohibit through-traffic movement or prevent

undesirable turns. Street closures may be appropriate

where large volumes of through-traffic or “short-cut”

maneuvers create unsafe conditions in a residential

environment.

Design Considerations:

• Where proposals are likely to lead to a reduction

in access, prior consultation with residents at

early stages of planning and design is especially

important to minimize opposition.

• The benefits of exempting bicyclists should be

carefully considered in all cases.

• Bicycle gaps should be designed to minimize the

risk of obstruction by parked vehicles. Painting

a bicycle symbol and other directional markings

on the road in front of the bicycle gap has

proven to be effective.

• Bollards can reduce the parking obstruction.

• Bollards should be lighted or reflectorized to be

visible at night.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 13

TRAFFIC CALMING

• The design of bicycle gaps should permit good

visibility of adjacent roads.

• Signing should acknowledge the continued

route as a through one for bicyclists.

• Clearly defined parking can reduce the problem

of parked cars blocking the closure and bicycle

gap.

• Police and fire departments should be consulted

early in the design process to determine emer-

gency access requirements. Often, removable

bollards, crash gates, and card or key-operated

gates can satisfy these requirements, combined

with parking restrictions. A 20-foot-wide clear

path is needed for emergency access.

• Tree planting, benches, and textured paving can

enhance appearance.

• Street closures are recommended only after full

consideration of all expected turning and

reversing movements, including those of refuse

trucks, fire trucks, and other large vehicles.

Partial Street Closures

Access to or from a street is prohibited at one end,

with a no-entry sign and barrier restricting traffic in

one direction. The street remains two-way, but

access from the closed end is permitted only for

bicyclists and pedestrians.

Design Considerations:

• Bicycle and pedestrian exemp-

tions should be provided as a

general rule, designed to

minimize the likelihood of

obstruction by parked vehicles.

• All signing should acknowledge

the continued existence of the

route as a through one for

bicyclists and pedestrians.

Driveway Links

A driveway link is a partial street

closure, where the street character is

significantly changed so it appears

roadway is narrowed and defined with textured or

colored paving. A ribbon curb or landscaping may be

used to delineate roadway edges. “Reclaimed”

roadway area is converted to pedestrian facilities and

landscaping.

This is a very effective method of changing the initial

impression of the street. If done right, drivers will not

be able to see through. It appears as a road closure,

yet allows through traffic.

The driveway link can provide access to small groups

of homes and is especially applicable to planned

residential developments. The “go slow” feel of the

driveway link is enhanced by design standards that

eliminate vertical curb and gutter and use a relatively

narrow driveway cross-section. A ribbon curb may be

used to protect roadway edges.

4. Traffic diversion.

Traffic diversion is one of the most widely applied

traffic-calming concepts. It includes all devices that

cause motor vehicles to slow and change direction to

travel around a physical barrier. Physical barriers used

to divert traffic in this fashion can range from traffic

circles to trees planted in the middle of the road. The

discussion that follows provides information on:

traffic diverters, traffic circles, chicanes, and “tortu-

ous” street alignments as traffic-calming devices.

Traffic Diverters

Traffic diverters are physical barriers installed at

intersections that restrict motor vehicle movements in

Diagonal road closures/diverters limit vehicular access, but allow emergency vehicles

to enter through removable bollards.to be a private drive. Typically, the

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 14

TRAFFIC CALMING

selected directions. The

diverters may be designed to

prevent right- or left-hand turns,

to block straight-ahead travel

and force turns to the right or

left, or create a “T” intersection.

In all cases, paths, cut-throughs,

or other provisions should be

made to allow bicyclists and

pedestrians access across the

closure.

Traffic diverters can take many

forms. Here are two examples:

(1) Diagonal road closure/

diversion.

Straight-through traffic move-

ments are prohibited. Motorists are diverted in one

direction only.

Advantages:

• Through-traffic is eliminated.

• Area for landscaping is

provided.

• Conflicts are reduced.

• Pedestrian safety is in-

creased.

• Can include a bicycle

pathway connection.

Disadvantages:

• Will inconvenience residents

in gaining access to their

properties.

• May inhibit access by

emergency vehicles unless

street names are changed.

• Will move through traffic to

other streets if not back to

the arterial.

Example:

Eugene, Oregon has used diagonal diverters with

positive community response. Eugene installs the

The splitter islands should be raised and

landscaped to prevent left-turning vehicles from

taking a short cut to avoid driving around the

outside of the island.

Example of an integrated traffic-calming plan.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 15

TRAFFIC CALMING

Traffic Circles

Small traffic circles (center island approximately 4

meters in diameter) can be used as traffic-calming

devices at intersections, reducing vehicle speeds. A

roundabout is a channelized intersection at which all

traffic moves counterclockwise around a central

traffic island. These islands may be painted or

domed, mountable elements may be curbed, and may

include landscaping or other improvements.

Advantages:

• Crashes reduced by 50 to 90 percent when

compared to two-way and four-way stop signs

and other traffic signs by reducing the number of

conflict points at intersections.

• Effective in reducing motor vehicle speeds.

Success, however, depends on the central island

being sufficiently visible and the approach lanes

engineered to deflect vehicles, preventing

overrun of the island. Overrunnable

roundabouts on straight roads are less likely to

produce the desired speed reduction.

Roundabout Accident Study

In 1989, a survey of crashes at mini-roundabouts

examined years of crash data for 447 sites in

England, Wales, and Scotland.

Key survey findings were:

• Mini-roundabouts were most commonly used

on streets with speed limits of 30 mph or less.

diverters on a temporary basis

to get neighborhood feedback

before making a permanent

installation. Two types of

diagonal diverters are used —

some are landscaped, while

others are just guardrails. Both

types have openings for

bicycles. These have been

supported by nearby residents.

Seattle installed truncated

diagonal diverters, which allow

right-turn movements around

one end of the diverter. The

Engineering Department found

that these diverters were

disruptive to neighborhood

traffic and has focused instead on installation of

traffic circles to control neighborhood traffic prob-

lems. Problems experienced with diverters included:

(1) travel time and distance increased for all users; (2)

local residents were diverted to other streets; (3)

visitors and delivery services were often confused

and delayed; and (4) emergency vehicle response

times were potentially increased.

(2) Turning-movement diverters.

This type of diverter is designed to prevent cut-

through traffic at the intersection of a neighborhood

street with a major street or collector. It prevents

straight-through movements and allows right turns

only into and out of the neighborhood.

Advantages:

• Effective at discouraging cut-through traffic.

• Relatively low cost.

• Creates sense of neighborhood entry and

identity.

Disadvantages:

• Limits resident access. Should be installed as

part of overall neighborhood circulation im-

provements to ensure reasonable convenience

for residents.

• Motorists may try to override the diverter to

make prohibited turns unless vertical curbs,

barriers, landscaping, or other means are used to

discourage such actions.

Traffic circles can be designed to accommodate large vehicles and emergency access

without undue restrictions.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 16

TRAFFIC CALMING

Where possible, cyclists should be provided with cycle slips which enable them to bypass

speed humps.

• Mini-roundabouts were found to have a far

lower overall accident rate than that of signalized

intersections with equivalent speed limits.

• Looking only at crashes involving bicycles, the

study showed that four-arm mini-roundabouts

have about the same involvement rate (accidents

per million vehicles of that type entering the

intersection) as do conventional, four-legged,

signalized intersections.

Comparative Accident Rates:

Signalized intersections:

2.65 accidents/intersection/year

34 accidents per 100 million vehicles

20% resulted in serious or fatal injury

Roundabouts:

0.83 accidents/intersection/year

20 accidents per 100 million vehicles

19% resulted in serious or fatal injury

Both types of intersections compared have 30-mph

speed limits and are four-legged intersections.

Splitter islands are the islands placed within a leg of

the roundabout, separating entering and exiting

traffic and designed to deflect entering traffic. They

are designed to prevent hazardous, wrong-way

turning movements.

These islands are important design elements and

should be provided as a matter of routine, wherever

feasible. Without splitter islands, left-turning

motorists have a tendency to

shortcut the turn to avoid

driving around the outside of

the central island. The islands

should, preferably, be raised

and landscaped. If this is not

possible, painted island

markings should be provided.

Design Considerations:

• Roundabouts should

preferably have sufficiently

raised and highly visible

centers to ensure that

motorists use them, rather

than overrunning.

• Clear signing is essential.

• Complementary speed reduction measures such

as road humps on the approach to roundabouts

can improve safety.

• The design of roundabouts must ensure that

bicyclists are not squeezed by other vehicles

negotiating the feature. Yet, where possible,

adequate deflection must be incorporated on

each approach to enforce appropriate entry

speeds for motor vehicles.

Example: Seattle Neighborhood Traffic Control

Program

The Seattle Engineering Department (SED) has

experimented since the 1960’s with a variety of

neighborhood traffic control devices. The major

emphasis of the SED Neighborhood Traffic Control

Program is installing traffic circles (roundabouts) at

residential street intersections. City staff report that

about 30 circles are built each year. A total of

approximately 400 circles have been installed to date.

Each circle costs about $5,000 to $6,000.

In Seattle, a traffic circle is an island built in the

middle of a residential street intersection. Each circle

is custom-fitted to the intersection’s geometry; every

circle is designed to allow a single-unit truck to

maneuver around the circle without running over it.

A 2-foot concrete apron is built around the outside

edge of the circle to accommodate larger trucks.

Large trucks, when maneuvering around the circle,

may run over the apron. The interior section of the

circle is usually landscaped.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 17

TRAFFIC CALMING

These pavement markings at a median refuge not only delineate the crossing for motorists,

but also cue pedestrians about the location of the roadway edge.

• Where full closure or speed humps are not

feasible, chicanes may be used to reduce traffic

speeds. Many different layouts are possible,

including staggered parking (on alternating sides

of the road).

Tortuous Roads

Roads can be designed to meander or jog sharply,

slowing traffic and limiting views to discourage

speeding. This technique can incorporate use of cul-

de-sacs and courtyards.

Design Considerations:

Tortuous roads are generally planned as part of the

design stage of a new road layout, rather than being

superimposed on an existing layout. The siting of

buildings is used to create a meandering road.

SED coordinates the design and construction of each

circle with the Seattle Fire Department and school

bus companies.

Traffic circles are installed at the request of citizens

and community groups. Because there are more

requests than funding to build them, SED has created

a system for evaluating and ranking the requests.

Before a request can be evaluated, a petition request-

ing a circle must be signed by 60 percent of the

residents within a one-block radius of the proposed

location. Then, the intersection’s collision history,

traffic volume, and speeds are studied.

Chicanes

Chicanes are barriers placed in the street that require

drivers to slow down and drive around them. The

barriers may take the form of landscaping, street

furniture, parking bays, curb extensions, or other

devices.

The Seattle Engineering Department has experi-

mented with chicanes for neighborhood traffic

control. It has found chicanes to be an effective

means of reducing speed and traffic volumes at

specific locations under certain circumstances. A

demonstration project at two sets of chicanes

showed:

• Reduction of traffic volumes on the demonstra-

tion streets.

• Little increase in traffic on adjacent residential

streets.

• Reduced motor speeds and

collisions.

• Strong support for perma-

nent installation of chicanes

by residents (68 percent).

Design Considerations:

• Consideration should be

given to safe bicycle travel.

Bicycle bypasses and signs

to indicate directional

priority are suggested.

• A reduction in sight lines

should not be used in

isolation to reduce speeds,

as alone, this could be

potentially dangerous. A reduction in sight lines

may be appropriate to avoid excessive land

taking or as a reinforcing measure only where

other physical features are employed that reduce

speed.

• Chicanes offer a good opportunity to make

environmental improvements through planting.

However, preference should be given to low-

lying or slow-growing shrubs to minimize

maintenance and ensure good visibility.

• Measures should be employed to ensure that

chicanes are clearly visible at night.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 18

TRAFFIC CALMING

given to maintaining as direct a route as possible

for bicyclists.

• Tortuous roads (a.k.a. serpentines) are under

study, but have not yet been approved for use in

Portland. If approved, they would be limited for

use on two-lane or fewer residential streets.

• Road design is limited by AASHTO standards

for transition taper lengths.

• This traffic-calming device may require signifi-

cant parking removal and should be used where

parking removal is not an issue.

5. Surface texture and visual devices.

This category of traffic-calming devices includes

signing, pavement marking, colored and textured

pavement treatments, and rumble strips. These

devices provide visual and audible cues about the

traffic-calmed area. Colors and textures that contrast

with those prevailing along the roadway alert

motorists to the need for alertness, much as con-

spicuous materials increase bicyclist and pedestrian

visibility. Signs and pavement markings also provide

information about applicable regulations, warnings,

and directions.

Signing and Pavement Markings

Installation of directional, warning, and informational

signs and pavement markings should conform to

MUTCD guidelines, as applicable. Traffic-calming

devices may be new to many people in the United

States and the signs and markings will help minimize

confusion and traffic conflicts.

Design Considerations:

• A part of the sign/pavement marking approach

to mitigating traffic in residential areas includes

painting of stripes/lines on the roadway and

other patterns that are designed to have a

psychological impact on drivers. Although such

patterns are basically intended to slow vehicles

rather than reduce traffic, they should make

passage over residential streets less desirable

than if the roadway were untreated, in effect,

encouraging the use of alternative routes.

• Many of the patterns tried have had only

marginal success. In a few cases, the average

speed increased slightly. A pattern that is

successful is that of painting transverse bands.

Painted lines are applied to the

road at decreasing intervals

approaching an intersection or

“slow-down” point. They are

intended to give the impression

of increasing speed and

motorists react by slowing

down.

Pavement Texturing and

Coloring

The use of paving materials

such as brick, cobbles, concrete

pavers, or other materials that

create variation in color and

texture reinforces the identity of

the area as a traffic-restricted

zone.

Pavement treatments can be applied to the entire traffic-calmed area or limited to specific

street uses. The texture or color should be a noticeable contrast to the approaching

roadways if speeds are to be reduced.

• Designers should be aware of the need for

accessibility to residential properties, both in

terms of servicing and the needs of the indi-

vidual. Tortuous roads will prove to be

unpopular if they severely restrict accessibility.

• Where traffic is deliberately diverted onto a

tortuous route — to avert town center conges-

tion, for example — consideration should be

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 19

TRAFFIC CALMING

Model of a “woonerf.”

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 20

TRAFFIC CALMING

Design Considerations:

• The choice of materials should ensure that they

do not pose a danger or deterrent to bicyclists.

Cobbles present special difficulties, particularly

for vehicles with narrow wheels and without the

benefit of suspension. Such treatment is

particularly discouraging for bicyclists on steep

slopes, making it harder to maintain momentum

when riding uphill. Thus, as a general rule,

cobbles should not be employed. Similarly,

pavers with chamfered edges impair a bicyclist’s

stability and should be avoided.

• The color and texture of the street surface are

important aspects of the attractiveness of many

residential streets. The variation from asphalt or

concrete paving associated by most people with

“automobile territory” signals to the motorist

that he or she has crossed into a different,

residential zone where pedestrians and bicyclists

can be expected to have greater priority.

Putting the Design Techniques to Work: Selected

Examples of Traffic Calming

Most traffic-calmed streets utilize a combination of

the devices just discussed. The following are some

examples: the woonerf, entry treatments, shared

streets, and other techniques (bicycle boulevards,

modified street design, modified intersection design,

channelization changes, traffic calming on a major

road, slow streets, transit streets, and pedestrian

zones).

1. The woonerf.

A woonerf (or “living yard”)

combines many of the traffic-

calming devices just discussed

to create a street where pedestri-

ans have priority and the line

between “motor vehicle space”

and “pedestrian (or living)

space” is deliberately blurred

(see the model of a woonerf).

The street is designed so

motorists are forced to slow

down and exercise caution.

Drivers, the Dutch say, do not

obey speed limit signs, but they

do respect the design of the

street.

The woonerf (plural — woonerven) is a concept that

emerged in the 1970’s as increased emphasis was

given by planners to residential neighborhoods.

People recognized that many residential streets were

unsafe and unattractive and that the streets, which

took up a considerable amount of land area, were

used for nothing but motor vehicle access and

parking. Most of the time, the streets were empty,

creating a “no-man’s land” separating the homes

from one another.

The Dutch, in particular, experimented extensively

with street design concepts in which there was no

segregation between motorized and non-motorized

traffic and in which pedestrians had priority.

A law passed in 1976 provided 14 strict “design

rules” for woonerfs and resulted in construction of

2,700 such features in the following seven years.

The woonerven were closely evaluated, with the/

following findings:

• Injury accidents were reduced by 50 percent.

• Vehicle speeds were reduced to an average of 8

to 15 mph (13 to 25 km/h).

• Nationally, 70 percent of the Dutch population

thought woonerven to be attractive or highly

attractive.

• Non-motorized users assessed woonerven more

positively than motorized users.

The distinction between sidewalks and roadway is blurred in woonerfs.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 21

TRAFFIC CALMING

• Feedback from residents living on woonerfs was

very positive. They appreciated the low traffic

volumes and absence of cut-through traffic, but

considered the larger play areas and other

improvements to the street environment to be

even more important benefits.

Woonerf Design Principles:

Following evaluation of the woonerven, the Dutch

law was amended (July 1988) to allow greater design

flexibility, replacing the design rules with six basic

principles.

(1) The main function of the woonerf shall be for

residential purposes. Thus, roads within the

“erf” area may only be geared to traffic terminat-

ing or originating from it. The intensity of traffic

should not conflict with the character of the

woonerf in practical terms: conditions should

be optimal for walking, playing, shopping, etc.

Motorists are guests. Within woonerven, traffic

flows below 100 vehicles per hour should be

maintained.

(2) To slow traffic, the nature and condition of the

roads and road segment must stress the need to

drive slowly. Particular speed-reduction features

are no longer mandated, so planners can utilize

the most effective and appropriate facilities.

(3) The entrances and exits of woonerven shall be

recognizable as such from

their construction. They

may be located at an

intersection with a major

road (preferable) or at

least 20 meters (60 feet)

from such an intersection.

(4) The impression shall not

be created that the road is

divided into a roadway

and sidewalk. Therefore,

there shall be no continu-

ous height differences in

the cross-section of a

road within a woonerf.

Provided this condition is

met, a facility for pedestri-

ans may be realized.

Thus, space can be designated for pedestrians

and a measure of protection offered, for example,

by use of bollards or trees.

(5) The area of the road surface intended for parking

one or more vehicles shall be marked at least at

the corners. The marking and the letter “P” shall

be clearly distinguishable from the rest of the

road surface. In shopping street “erfs”

(winkelerven), special loading spaces can be

provided, as can short-term parking with time

limits.

(6) Informational signs may be placed under the

international “erf” traffic sign to denote which

type of “erf” is present.

2. Entry treatment across intersections.

Traffic-calming devices can be combined to provide

an entry or “gateway” into a neighborhood or other

district, reducing speed though both physical and

psychological means. Surface alterations at intersec-

tions with local streets can include textured paving;

pavement inserts; or concrete, brick, or stone

materials. At the entry, the surface treatment can be

raised as high as the level of the adjoining curb.

Visual and tactile cues let people know that they are

entering an area where motor vehicles are restricted.

Eugene, Oregon installs curb extensions at entrances

to neighborhood areas, usually where a residential

The conversion of a 58-foot roadway. Elimination of one travel lane in each direction

creates space for bicyclists.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 22

TRAFFIC CALMING

street intersects an arterial. The curb extension is

placed to prevent motor vehicle traffic from cutting

through the neighborhood. The curb extension is

signed as a neighborhood entrance or exit. Most of

the street remains two-way, but one end becomes a

one-way street. Compliance by motor vehicles is

mostly good. Bikes are allowed to travel both ways

at all curb extensions.

3. Bicycle boulevards.

The City of Palo Alto, California has moved beyond

spot traffic-calming treatments and has created

bicycle boulevards — streets on which bicycles

have priority.

The purpose of a bicycle boulevard is to provide:

• Throughway where bicycle movements have

precedence over automobiles.

• Direct route that reduces travel time for bicy-

clists.

• Safe travel route that reduces conflicts between

bicyclists and motor vehicles.

• Facility that promotes and facilitates the use of

bicycles as an alternative transportation mode

for all purposes of travel.

The Palo Alto bicycle boulevard is a 2-mile stretch of

Bryant Street — a residential street that runs parallel

to a busy collector arterial. It was created in 1982

when barriers were fitted to restrict or prohibit

through motor vehicle traffic, but to allow through

bicycle traffic. In addition, a number of stop signs

along the boulevard were removed. An evaluation

after 6 months showed a reduction in the amount of

motor vehicle traffic, a nearly twofold increase in

bicycle traffic, and a slight reduction in bicycle traffic

on nearby streets.

The City also found that anticipated problems failed

to materialize and concluded that a predominately

stop-free bikeway — on less traveled residential

streets — can be an attractive and effective route for

bicyclists. The bicycle boulevard bike traffic

increased to amounts similar to those found on other

established bike routes.

The bicycle boulevard continues to function as a

normal local city street, providing access to resi-

dences, on-street parking, and unrestricted local

travel. The City received complaints about the visual

appearance of the initial street closure barriers (since

upgraded with landscaping), but is unaware of any

other serious concerns of nearby residents.

Plans for the extension of the bicycle boulevard

through downtown Palo Alto were approved by the

City Council in the summer of 1992. Included in this

extension was the installation of a traffic signal to

help bicyclists cross a busy arterial.

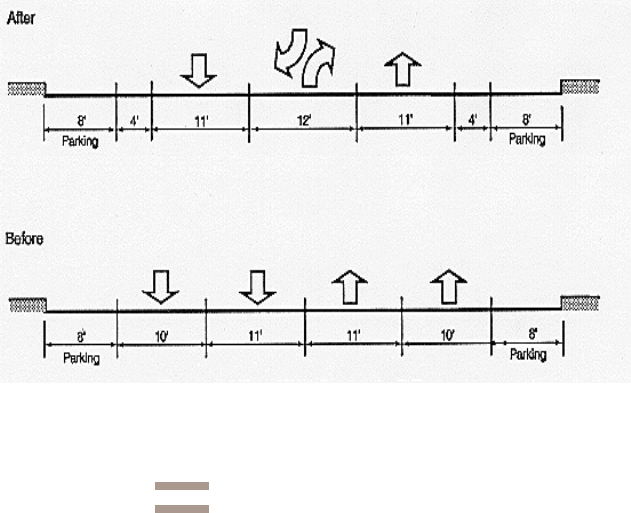

4. Channelization changes.

The Seattle Engineering Department is changing

some of its streets from four lanes to two lanes. with

a center left-turn lane. These channelization changes

can provide extra room for bicycle lanes or a wide

lane for cars and bikes to share.

Numerous comments from users of some of those

streets say motor vehicle speeds seem to have

decreased. One street in particular, Dexter Avenue

North, is a popular commuting route to downtown

Seattle for bicyclists.

Traffic counts on the street show bicyclists make up

about 10 to 15 percent of the traffic at certain times

during the day. The rechannelization had little or no

effect on capacity, reduced overtaking accidents, and

made it easier for pedestrians to cross the street (by

providing a refuge in the center of the road).

11.5 Exercise

Do one of the following exercises:

1. Choose a site-specific location (such as two to

three blocks of a local street) where fast traffic or

short cuts are a problem. Conduct a site analysis

to determine problems. Prepare a detailed site

solution that incorporates several traffic-calming

devices. Illustrate with drawings and describe

the anticipated changes in traffic speed.

2. Prepare a traffic-calming solution for an entire

neighborhood or downtown area that illustrates

an area-wide approach to slowing traffic.

Conduct a site analysis to determine problem

areas. Illustrate your solutions and describe the

anticipated changes in traffic speed and flow.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 23

TRAFFIC CALMING

11.6 References

Text and graphics for this lesson were derived from

the following sources:

Federal Highway Administration, National Bicycling

and Walking Study–Case Study No. 19: Traffic-

Calming, Auto-Restricted Zones, and Other Traffic

Management Techniques–Their Effects on Bicycling

and Pedestrians, 1994.

Federal Highway Administration, Pedestrian &

Bicyclist Safety and Accommodation–Participation

Handbook, NHI Course #38061, 1996.

Hass Klau, Illustrated Guide to Traffic Calming,

Institute of Transportation Engineers, 1990.

For more information on this topic, refer to:

J. Cleary, Cyclists and Traffic Calming, Cyclists

Touring Club, Godalming, U.K., 1991.

R. Ewing and Kooshian, “U.S. Experience With

Traffic Calming,” ITE Journal, August 1997, pp. 28-

33.

Cynthia Hoyle, Traffic Calming, Planning Advisory

Service Report No. 456, American Planning Associa-

tion, 1995.

Institute of Transportation Engineers, Recommended

Guidelines for the Design and Application of Speed

Humps, 1993.

National Cooperative Highway Research Program

(NCHRP), Research Synthesis on Roundabouts,

NCHRP Synthesis 264.

Traffic Calming in Practice– An Authoritative

Sourcebook With 85 Illustrative Case Studies

(available through ITE), Landor Publishing, London,

1994.

FHWA COURSE ON BICYCLE

AND PEDESTRIAN TRANSPORTATION

FHWA

11 - 24

TRAFFIC CALMING