Page 1 GAO-24-106263 Military Spouse Employment

Employment is a top concern for spouses of active-duty military service

members, according to the Department of Defense (DOD). Military spouses may

face challenges obtaining or maintaining employment that meets their financial or

professional needs due to the demands of military life. These demands include

frequent moves, overseas deployments, and irregular work hours for the service

member.

Some military spouses may pursue part-time employment—although it generally

pays less and provides fewer benefits than full-time employment—because they

can more quickly find part-time jobs. Other military spouses may work part time

because it allows them to better balance work with caregiving or other

responsibilities. However, managing military life and limited or unsatisfactory

employment options could create additional stress for military spouses and

families. This could, in turn, affect military families’ decisions about whether the

service member remains in the military.

House Report 117-397 includes a provision for GAO to examine the

characteristics and experiences of military spouses who work part time. We are

providing information on the size, demographic characteristics, employment

experiences, and health and well-being of this workforce.

• In 2021, about a third of employed military spouses worked part time based

on our estimates using data from DOD’s most recent survey of military

spouses. Overall, we estimate that there were about 540,000 civilian spouses

of active-duty military service members. The vast majority—around 90

percent—were women. Additionally, we estimate that about half of all military

spouses (270,000) were employed in 2021. Of these individuals who were

employed, about a third (88,000) worked part time.

• Military spouses we interviewed who worked part time reported various

employment challenges, including being underpaid or overqualified for their

job, lacking opportunities for career advancement, and not earning retirement

benefits. Although many other civilian workers may experience similar

challenges, military spouses discussed how military life—including frequent

moves—contributes to their employment challenges.

• In DOD’s 2021 survey, military spouses who worked part time reported levels

of satisfaction with military life that were similar to military spouses who

worked full time. However, DOD reported that, overall, military spouses’

satisfaction with military life has been decreasing since 2012.

U.S. Government Accountability Office

Military Spouse Employment: Part

-Time

Workforce Characteristics and Perspectives

GAO

-24-106263

Q&A

Report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

February

8, 2024

Why This Matters

Key Takeaways

Errata: On May 9,

2024, GAO

reissued this

report to revise a

paragraph on

page 4 and

related endnote 6

to clarify that the

administrative and

survey data we

analyzed

measured military

spouse

employment over

different

timeframes.

Page 2 GAO-24-106263 Military Spouse Employment

We estimate that about 88,000 of approximately 540,000 military spouses who

were civilians worked part time in 2021, according to our analysis of data from

DOD’s Survey of Active Duty Spouses.

1

The 2021 survey data were the most

recent and comprehensive data available on the employment status and well-

being of military spouses at the time of our review. To focus on employment

issues outside of military service, our analysis did not include military spouses

who were active-duty service members themselves, only military spouses who

were civilians. Our estimates are described in more detail below.

Overall employment status

The employment status of the estimated 540,000 military spouses—of whom

around 90 percent were women—was as follows:

• Employed. About half (270,000) worked for pay in either a full-time or part-

time capacity.

2

• Not employed and not seeking work. Around a third (196,000) were neither

working nor seeking work for various reasons, such as attending school or

caring for children or other family members.

• Not employed but seeking work. The smallest segment (about 74,000)

were unemployed but actively seeking work.

Part-time employment

Of the estimated 270,000 employed military spouses, about 88,000 or a third (32

percent) worked part time (see fig.1).

3

Within the general civilian population,

about 19 percent of married and employed individuals worked part time in 2021,

according to our analysis of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Various

factors could help explain this difference, including age, gender, educational

level, or other demographic characteristics.

Figure 1: Estimated Percentage of Employed Military Spouses Who Worked Part

Time or Full Time in 2021

Note: Estimates in the figure have a maximum margin of error of ±2 percentage points within a 95 percent

confidence interval. We rounded the estimated number of employed military spouses to the nearest thousand

individuals.

We found that employed military spouses were more likely or less likely to work

part time based on various demographic characteristics in our statistical model

(see fig. 2).

4

How many military

spouses worked part

time?

What do we know about

the

demographic

characteristics

of

military spouses who

worked part time?

Page 3 GAO-24-106263 Military Spouse Employment

Figure 2: Selected Characteristics of Employed Military Spouses that Indicated

Increased or Decreased Likelihood of Working Part Time in 2021

Note: In our statistical model, these selected characteristics were statistically significant at least at the 95

percent confidence level. Our model solely included employed military spouses and did not explain why

different groups of military spouses were more likely or less likely to work part time. To examine potential

reasons why the groups we identified were more likely or less likely to work part time, we would need to explore

a wider range of characteristics via an experimental design, which was outside the scope of this study.

a

We categorized the self-reported careers of military spouses into blue-collar and white-collar jobs. We defined

blue-collar jobs as those that typically involve manual labor or do not generally require a 4-year college degree

(e.g., customer service representatives, commercial drivers). In contrast, we defined white-collar jobs as those

that tend to require higher levels of education or entail administrative and managerial work (e.g., teachers,

nurses).

b

Based on the available data, we compared employed military spouses who never experienced a military move

to those who experienced at least one move. We could not examine the potential impact of multiple military

moves.

Additionally, we found that military spouses were more likely or less likely to work

part time based on various demographic characteristics of their service member

spouse (see fig.3).

Figure 3: Selected Characteristics of Service Members that Indicated Increased or

Decreased Likelihood of Their Spouse Working Part Time in 2021

Note: In our statistical model, these selected characteristics were statistically significant at least at the 95

percent confidence level. Our model solely included employed military spouses and did not explain why

different groups of military spouses were more likely or less likely to work part time. To examine potential

reasons why the groups we identified were more likely or less likely to work part time, we would need to explore

a wider range of characteristics via an experimental design, which was outside the scope of this study.

a

These results included service members from DOD’s first four pay grades (E-1 through E-4) out of nine total

pay grades for enlisted service members.

b

About 83 percent of service members were male in 2021 according to DOD data. Nonetheless, we found this

was a statistically significant characteristic associated with increased likelihood of employed military spouses

working part time. We did not examine any potential dynamics between the gender of the service member and

the gender of the individual to whom they were married.

c

The statistically significant category included spouses of service members who had not been deployed since

September 11, 2001 (in comparison to spouses of service members who had been deployed since that time).

For a complete list of the characteristics included in our statistical model,

including characteristics that we did not find to be associated with increased or

decreased likelihood of working part time, see appendix I.

Page 4 GAO-24-106263 Military Spouse Employment

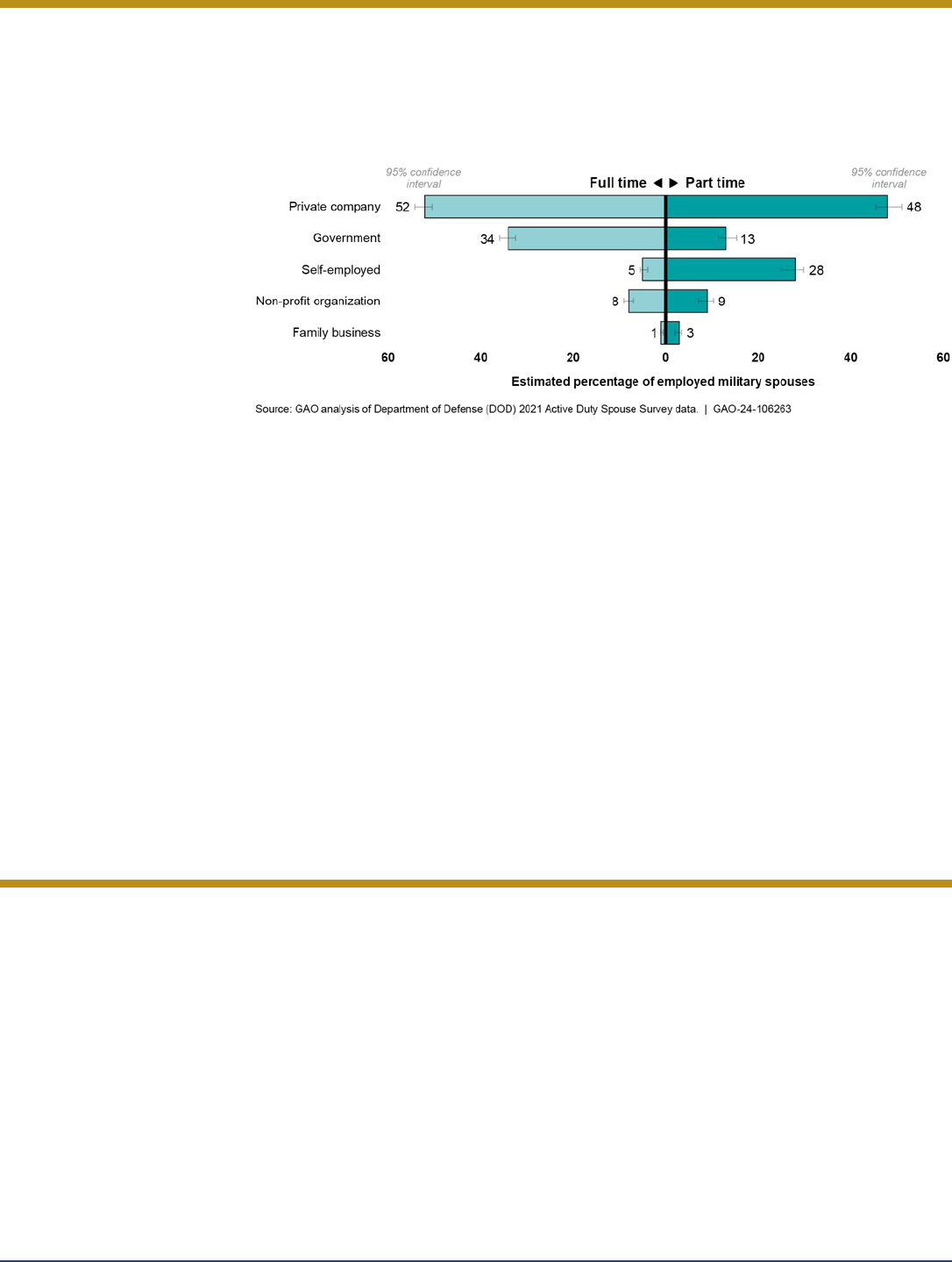

The largest employment sector was private companies, in which about half of

employed military spouses worked part time or full time in 2021 (see fig. 4). In

contrast, self-employment was more prevalent among the military spouses who

worked part time (28 percent) than among those who worked full time (5

percent).

5

Figure 4: Military Spouse Employment by Sector, 2021

Note: Estimates in the figure have a maximum margin of error of ±3 percentage points within a 95 percent

confidence interval.

Government was the third largest employment sector among military spouses

who worked part time, but the second largest among those who worked full time.

This sector included about 73,000 military spouses employed either part time or

full time across federal, state, and local governments.

Within the government sector, DOD employed a substantial number of military

spouses in civilian jobs. Over the course of 2021, about 46,000 military spouses

worked for DOD.

6

• DOD civil service positions. Of those 46,000 DOD-employed military

spouses, more than half (about 25,000) worked in federal civil service

positions at DOD, and mostly in full-time jobs. Among the positions they held

were budget analysts, information technology specialists, and nurses.

• Positions often at military bases. The remaining 21,000 DOD-employed

military spouses worked at entities that are often located on DOD military

bases that generate revenue (e.g., retail stores) or collect operating fees

(e.g., recreational facilities). Such positions included educational and training

instructors, food service workers, and retail store workers.

The 17 military spouses we interviewed from five discussion groups said they

worked part time because they needed flexible schedules to care for children or

to accommodate frequent military moves.

Child care needs

Nearly all military spouses we interviewed said they worked part time because

they were the primary caregivers for their children.

7

They said they needed

flexible jobs with reduced hours because their service member spouse was not

consistently or predictably able to contribute to child care.

8

For example, one

military spouse noted that her husband’s rotating schedule changed every few

months, and it was difficult to find an employer that would grant her that much

flexibility. Similarly, many military spouses noted that when the service member

was on duty, the military spouse needed to frequently function as a single parent,

responsible for all school drop-offs and pickups or grocery shopping, for

example.

What were the largest

employment sectors for

military spouses who

worked part time?

What were some

common

reasons

military spouses said

they worked part time?

Page 5 GAO-24-106263 Military Spouse Employment

Source: GAO transcription of discussion group recordings. | GAO-24-106263

Furthermore, getting help with child care was difficult, several military spouses

said. Some noted that child care costs were prohibitive or that child care services

were not readily available. Some other military spouses said that, due to

relocations, they did not have nearby friends or family members who could help

care for their children. For example, one military spouse noted that she would

prefer to work full time; however, it was not possible without family nearby to help

with her two young children.

Frequent moves

Many military spouses who worked part time also described the adverse effects

of frequent military moves on their employment opportunities, in some cases

leading them to take part-time work. Many spouses also noted that these moves

led to the end of their employment. For example, one military spouse said she

had to give up her full-time “dream job” when she moved from one country to

another. In general, many military spouses described how these moves made it

difficult to pursue work that paid more or that was better aligned with their

specific career goals and skills.

9

For example, one military spouse said she had

tried unsuccessfully for years to obtain a federal civil service job. After she finally

obtained one, she said her husband received a relocation order fewer than 30

days later. Her employer was unable to transfer her job to the new location.

Source: GAO transcription of discussion group recordings. | GAO-24-106263

Moreover, some military spouses said that moving their families was a time-

consuming process that took away from working. For example, they needed to

spend time locating schools or child care for their children or housing for their

families. One military spouse said that after a move the burden to establish new

routines for the family generally falls to the military spouse and that fulfilling these

responsibilities takes time away from searching for a job. A few others noted that

finding a new job after each move can also be time-consuming.

The military spouses we interviewed in our discussion groups reported various

employment challenges, including being underemployed (e.g., overqualified for a

job), lacking a career path or opportunities for advancement, and not earning

retirement benefits.

Underemployment

Nearly all of the 17 military spouses we interviewed expressed frustration with at

least one form of underemployment. While there is not a single, universal

measure of underemployment, it generally refers to working in a job that does not

meet one’s financial or professional needs. Below are examples of why military

spouses said their part-time jobs did not fully meet their needs.

What employment

challenges did military

spouses who worked

part time report?

Statement from a military spouse on the impact of child care needs

“I would like to be working full time; I have worked full time. But child care is the major limiting

factor. And it’s not just access to safe and affordable child care. When my spouse is on

temporary duty assignment, like right now, I am in single-parent mode. There is no backup…I do

not have family nearby.”

Statement from a military spouse on the impact of military moves

“We run into these problems when [moving with the military]. You are in a new place; you don’t

know anybody. I get into this rotation of, you get to a new [location], you get a not-so-good

job—a $13 an hour job. You do that for a year, get your schedule figured out, and then land a

great job making $80,000. Everything is going good, and then guess what? You get [military

move] orders and it’s time to move again.”

Page 6 GAO-24-106263 Military Spouse Employment

• Being underpaid. Nearly all the military spouses said they were not satisfied

with their current pay or perceived that they were underpaid compared to

their colleagues. For example, one military spouse said part-time work

allowed her to “be a mom” but it did not provide enough money “to make

ends meet” or to pay for travel to visit family out of state. Some military

spouses said they felt that gaps in their work experience and shorter periods

of employment—both of which were often due to frequent military moves—

played a role in their pay levels. For example, one military spouse said she

had to start at the bottom of the pay scale with each move. Several also said

that jobs with better pay might not be readily available in their new location;

they often found that their employment options were limited to entry-level

positions or lower-paying jobs, such as retail or child care positions.

• Working outside their professional field. Several military spouses said

they had to take jobs outside their professional fields because they could not

find relevant jobs in their locations. For example, one spouse who could not

find work as a paralegal when she accompanied her husband to an overseas

location instead worked as a fitness instructor. Another spouse said that she

would prefer to work in public policy, the field in which she held a master’s

degree; however, her husband’s frequent moves prevented her from building

necessary professional expertise in a policy area.

• Seeking a full-time job. Although many spouses said they were unable to

work full time for the reasons described previously, some said they could

work full time if an employer offered that or if child care were more readily

available. For example, one teacher with decades of experience and relevant

education said she was not offered full-time positions while she was teaching

overseas. She said the schools she taught at generally provided full-time

positions only to teachers who could commit to staying in the country for a

certain amount of time.

Source: GAO transcription of discussion group recordings. | GAO-24-106263

Lack of career path

Many military spouses we interviewed expressed frustration with their career

path. A few stated that they had jobs but wanted careers. As one military spouse

explained it, the two words have different implications; a part-time job is not your

career, and she found it less fulfilling. Another spouse said she settled for

unsatisfactory jobs because she was not offered positions that aligned with her

career goals. Some spouses said they believed employers were unwilling to hire

military spouses because of their frequent moves. Similarly, several other

spouses said they found it difficult to obtain raises and promotions, in part,

because of frequent moves and the resulting lack of job continuity on their

resumes.

Source: GAO transcription of discussion group recordings. | GAO-24-106263

Statement from a military spouse about the lack of career options

“Women in our forties are ready for that career move, and our kids are old enough that we are in

a position…to make a career move. But, again, we’re subject to deployments, [military] moves,

and availability [of jobs]…it’s extremely limited. So, we just continue to take the [part-time] job.”

Statement from a military spouse about her level of pay

“My plan was to work full time when my husband retired…but because of my employment

gaps and career change, I could not find employment that paid enough. So, I’m continuing to

work part time so that I can say I’ve got 3 or 4 years’ experience in [my] career field… [My

husband and I have] applied to literally the same company, and he got offered $10,000 more

than me, even though he didn’t have a degree [like me].”

Page 7 GAO-24-106263 Military Spouse Employment

Lack of retirement benefits

Many military spouses expressed concern about their lack of retirement savings,

noting that their part-time jobs generally did not offer retirement benefits.

10

Some

others said they did not stay in previous jobs long enough to qualify for their

employers’ retirement account matching contributions, or said they experienced

challenges rolling over funds into new retirement accounts when they left their

jobs. One military spouse explained that it is common among military spouses to

have “a trickle” of retirement contributions at one job, and then “a trickle” from

another, but nothing if they are working as independent contractors. She also

lamented that “it hurts my brain” to navigate all the retirement account transfers.

Some military spouses said their lack of individual retirement savings and low

earnings made them feel dependent on their service member spouse for their

long-term financial security. For example, one military spouse said that because

she made trade-offs like accepting jobs without retirement benefits in exchange

for job flexibility to care for children, she was dependent on her service member

spouse to sustain her financially in retirement.

To help manage the above employment challenges, many military spouses told

us that having more opportunities for remote work and other portable jobs that

they could keep after moving would greatly improve their ability to maintain stable

employment and develop their careers. Many military spouses also expressed a

desire for better access to federal civil service jobs, including more transparency

in the hiring process and more portable positions.

11

Source: GAO transcription of discussion group recordings. | GAO-24-106263

Military spouses who worked part time reported similar levels of physical and

mental health in recent years as military spouses who worked full time. To

consider the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on military spouses’

responses to questions about their health and well-being in DOD’s 2021 survey,

we also analyzed available data in the 2019 survey on these topics.

12

Physical health

We estimate that in 2019 almost 60 percent of military spouses—whether

employed part time or full time—rated their general health as excellent or very

good. We could not compare how military spouses’ general health changed

between 2019 and 2021 because the 2021 survey did not ask military spouses to

rate their general health.

Mental health

Military spouses employed part time and full time generally reported similar levels

of mental health in 2021 and in 2019. However, we could not directly compare

military spouses’ mental health across both years because the 2021 survey used

a slightly different mental health measure.

• In 2021, DOD used a mental health index to measure how often military

spouses felt depressed, nervous, or anxious in the previous week. The

average mental health score for military spouses who worked part time was

not statistically different from those who worked full time.

13

How did military

spouses who worked

part time characterize

their

health?

Statement from a military spouse on the desire for job stability

“I never imagined it would be almost impossible to find steady, remote work as a military

spouse. Preferably it would be [within the federal civil service]. Because I would like stability. I

would very much like to know how much I will get paid every month. I would very much like to

have that work stability, so I am not always hustling.”

Page 8 GAO-24-106263 Military Spouse Employment

• However, after controlling for various characteristics of individual military

spouses and their service member spouse using the 2021 survey data, we

found that military spouses with the best mental health scores (lowest

incidence of mental health issues) were more likely to be employed full time

than part time.

14

In contrast, we did not find differences based on part-time

versus full-time employment among those with "moderate” or “high” levels of

mental health issues.

Although military spouses who worked part time scored slightly lower on a

financial well-being scale than those who worked full time, the average scores for

both groups were within a range that indicated a moderate level of financial well-

being in 2021. This financial well-being measure was one that DOD adapted from

an existing Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) scale and applied to

its military spouse survey data. Specifically, the average financial well-being

score for military spouses who worked part time in 2021 was approximately 56,

on a scale of 0 to 100, compared to 59 for military spouses who worked full time.

However, after controlling for various characteristics of individual military spouses

and their service member spouse, military spouses who worked part time were

less likely to have slightly below average scores (41-50) compared to those who

worked full time.

15

Nonetheless, we did not find differences based on part-time

versus full-time employment among military spouses with the lowest or highest

levels of financial well-being (scores of 0-40 or 61-100, respectively).

Military spouses who worked part time reported levels of satisfaction with military

life that were similar to the levels for other military spouses, including those who

worked full time.

• Almost half of military spouses who worked part time or full time said they

were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the military lifestyle.

16

However, DOD

reported that, overall, military spouses’ satisfaction with military life has been

decreasing since 2012 and was statistically lower in 2021 than in all previous

years.

17

DOD’s report did not include an assessment of why military spouses’

reported satisfaction with military life has decreased over time.

• More than half of military spouses—whether employed part time or full time,

unemployed but seeking work, or out of the workforce altogether—said they

supported the idea of their service member spouse remaining on active duty.

• Nonetheless, several military spouses who participated in our discussion

groups said their employment challenges were a factor in their family’s

discussions about whether to remain in military life. However, none of these

individuals said they were considering leaving military life until after their

spouse completes the 20 years of service that are required to qualify for a

defined benefit military pension.

18

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. DOD did not

have any comments on the report.

To estimate the size and demographic characteristics of military spouses who

worked part time, we analyzed data from DOD’s 2019 and 2021 surveys of

military spouses, the two most recent surveys available at the time of our review.

This biennial survey examines the experiences and attitudes of a generalizable

sample of military spouses on a range of topics, including employment, health

and well-being, and satisfaction with military life.

How did military

spouses who worked

part time characterize

their financial well

-

being?

How satisfied with

military life are military

spouses who worked

part time

?

Agency Comments

How GAO Did This

Study

Page 9 GAO-24-106263 Military Spouse Employment

To examine whether military spouse and service member characteristics and

military spouses’ perspectives about their health and well-being were associated

with their part-time or full-time employment status, we calculated descriptive

statistics and conducted quasi-binomial logistic regressions using the 2021

survey data.

19

Our analyses included military spouses who were legally married

to active-duty members of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force

(including Space Force) because those were the service branches included in

DOD’s survey. Our analyses did not include military spouses married to

members of the Coast Guard, which is within the Department of Homeland

Security. Additionally, since we sought to provide information on the military

spouse part-time workforce overall, we did not examine characteristics and

experiences of military spouses by service branch.

In our regression model, we accounted for demographic factors of employed

military spouses and service members, including age, gender, and race.

Additionally, we accounted for military experiences (e.g., military moves and

deployments) and military spouses’ attitudes about their employment, family’s

health and financial well-being, and military life. For the complete list of

characteristics included in our model, see appendix I. Associations we identified

were statistically significant at least at the 95 percent confidence level in our

regression model.

To consider the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on military spouses’

health and financial well-being, we analyzed available data on these topics using

the 2019 and 2021 DOD survey data. We then assessed whether our

conclusions differed depending on whether the data were from before (2019) or

during (2021) the pandemic. We did not identify any substantial differences within

the scope of our analyses.

To focus on employment issues outside of military service, our analysis included

only military spouses who were civilians. We did not include military spouses who

were active-duty service members themselves.

All percentage estimates in this report have a margin of error of plus or minus 10

percentage points or fewer.

To calculate the number of military spouses employed by DOD, we analyzed

DOD administrative data on civilian personnel for calendar years 2021 and 2022,

the most recent full years of data at the time of our review.

20

We determined that the DOD survey and administrative data were reliable for our

purposes. To assess whether the data were reliable, we interviewed DOD

officials about the agency’s processes for collecting and maintaining these data

and any potential data limitations relevant to our planned analyses. We also

conducted electronic tests for missing data, outliers, and obvious errors.

To describe the potential benefits and challenges of working part time, we

conducted five virtual discussion groups with a non-generalizable sample of 17

military spouses, including spouses of enlisted service members and officers in

any military service branch. We interviewed one of these 17 military spouses

individually rather than as part of one of our discussion groups due to scheduling

challenges. We selected discussion group participants by disseminating a short

online survey to collect information on their employment experiences. We

selected military spouses who said they (1) were married to a current or former

active-duty service member, (2) worked part time at some point while their

spouse was on active duty, (3) were not currently serving on active duty

themselves, and (4) had at least one child.

21

We also sought demographic

variation across our groups.

22

To characterize the views of these military spouses throughout this report, we

defined modifiers (e.g., “nearly all”) to quantify participants’ views as follows:

Page 10 GAO-24-106263 Military Spouse Employment

• “Nearly all” represents 14 to 17 participants,

• “Many” represents nine to 13 participants,

• “Several” represents six to eight participants,

• “Some” represents three to five participants, and

• “A few” represents two participants.

We interviewed representatives of three military service organizations—which we

selected based on their prior published work on military spouse employment

issues—to obtain examples of challenges related to part-time employment for

military spouses.

To obtain background information on the topic, we reviewed relevant peer-

reviewed literature and literature produced by non-academic, professional

organizations, including military service organizations and business groups, from

the past 10 years.

To obtain DOD’s perspectives on employment opportunities and challenges for

military spouses, we interviewed an official from DOD’s Office of Military

Community and Family Policy, which provides military spouse employment

assistance, among other services.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2022 to February 2024 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those

standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient,

appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence

obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on

our audit objectives.

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

For more information, contact: John D. Sawyer, Director, Education, Workforce,

Chuck Young, Managing Director, Public Affairs, [email protected], (202) 512-

4800.

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, Congressional Relations,

[email protected], (202) 512-4400.

Staff Acknowledgments: Meeta Engle (Assistant Director), Justin Gordinas

(Analyst in Charge), James Ashley, James Bennett, Tinae Bluitt, Denise Cook,

Morgan Jones, Christy Ley, Serena Lo, Cynthia Nelson, Afsana Oreen, Raquel

Qualls-Hampton, Paras Sharma, Meg Sommerfeld, and William Stupski.

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, Twitter, and YouTube. Subscribe to our

RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

This work of the United States may include copyrighted material, details at

https://www.gao.gov/copyright.

List of Addressees

GAO Contact

Information

Page 11 GAO-24-106263 Military Spouse Employment

Table 1: Variables Included in Regression Analysis of Employed Military Spouses (Part Time

or Full Time), 2021

Dependent variable: Likelihood of part-time employment among employed military

spouses

Demographic characteristics of military spouses and service members

Age, military spouse

Career field, military spouse

Child(ren) in household

Gender, both

Highest education level, both

Pay grade, service member

Race and/or ethnicity, both

Total household income

Service members' military experiences

Household relocated due to a change in the service member’s military base

Number of deployments for the service member since September 11, 2001

Military spouses’ attitudes on…

Needing to find a job that allows them to work more hours

Personality changes, if any, in their spouse after their spouse returned home from deployment

Satisfaction with military life

Their family’s financial well-being

Their mental health

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense (DOD) 2021 Survey of Active Duty Spouses data. | GAO-24-106263

1

DOD’s survey includes data on spouses of active-duty members of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps,

and Air Force (including Space Force). Based on our analysis of the 2021 survey data, we estimate

that about 546,000 military spouses were civilians. However, we could only estimate the

employment status of about 540,000 military spouses—based on how many reported their

employment status in the survey. Throughout our report, we rounded our estimated numbers of

military spouses to the nearest thousand individuals. All percentages we estimate from the 2021

survey data have a margin of error of plus or minus 10 percentage points or fewer.

2

This employment does not account for any unpaid work that military spouses may perform, such

as caring for children or other family members or volunteer work.

3

DOD estimated the same percentage of employed military spouses (32 percent) worked part time

in 2019 based on its previous survey.

4

Using the 2021 survey data, we conducted a regression analysis to account for demographic

characteristics and other factors that might be associated with employed military spouses working

either part time or full time. We reported on factors that we found to be statistically significant at

least at the 95 percent confidence level in our regression model.

5

Similar percentages of military spouses also reported being self-employed in DOD’s previous

survey in 2019, which was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

6

We calculated this number based on how many military spouses DOD identified in its monthly

administrative data on civilian employment over the course of 2021. In contrast, the 73,000 military

spouses who worked in federal, state, or local government positions that we discussed in the

preceding paragraph is a survey-based estimate of how many military spouses worked in

government at a single point in time in 2021 rather than over the course of the entire year.

7

To characterize the views of military spouses throughout this report, we defined modifiers (e.g.,

“nearly all”) to quantify participants’ views as follows: “Nearly all” represents 14 to 17 participants,

“many” represents nine to 13 participants, “several” represents six to eight participants, “some”

represents three to five participants, and “a few” represents two participants.

8

We previously identified similar child care challenges for military families, including frequent

moves, non-traditional work hours, and deployments. See GAO, Military Child Care: DOD Efforts to

Provide Affordable, Quality Care for Families, GAO-23-105518 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 2, 2023).

Appendix I: Variables

Included in Regression

Analys

is

Endnotes

Page 12 GAO-24-106263 Military Spouse Employment

9

We previously reported that frequent military moves and difficulty transferring occupational

licenses pose challenges for military spouses pursuing careers. See GAO, DOD Should Continue

Assessing State Licensing Practices and Increase Awareness of Resources, GAO-21-193

(Washington, D.C.: Jan. 27, 2021).

10

We previously estimated in 2015 that full-time workers were about 2.6 times more likely than part-

time workers to be eligible for a retirement savings program offered by their employer, after

controlling for various characteristics of individual workers such as age, education, gender, and

occupation. See GAO, Retirement Security: Federal Action Could Help State Efforts to Expand

Private Sector Coverage, GAO-15-556 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2015).

11

The President signed an executive order in June 2023 that, in part, directed certain federal

agencies to identify strategies for eliminating barriers to employment in the federal civil service for

military spouses. See Exec. Order No. 14,100, 88 Fed. Reg. 39,111 (June 15, 2023).

12

Compared to prior years, the 2021 survey was shorter and covered different topics. According to

DOD officials, the 2021 survey was modified because the Office of Management and Budget

requested a shorter survey as well as the addition of questions related to COVID-19 and food

security, among other topics.

13

In 2021, DOD’s mental health index ranged from 0 to 12, with higher scores representing higher

incidence of mental health issues. We categorized this range into 0-2 (low), 3-8 (moderate), and 9-

12 (high). We also found that in 2019 the average mental health scores for military spouses were

not statistically different based on part-time versus full-time employment.

14

For the list of the characteristics included in our regression model, see appendix I.

15

The CFPB Financial Well-Being Scale does not set parameters for “good” or “bad” scores, but it

can be used to establish benchmarks to analyze individuals’ financial well-being, according to

CFPB. We categorized scores based on ranges DOD used in its analysis of the 2021 survey data.

16

Even after controlling for various characteristics of individual military spouses and their service

member spouse, we did not find a difference in the reported satisfaction of military spouses who

worked part time compared to those who worked full time.

17

DOD, Office of People Analytics, Results From the 2021 Active Duty Spouse Survey, Report No.

2023-045 (Alexandria, VA: Feb. 9, 2023).

18

A defined benefit pension is an employer-sponsored retirement plan that typically provides a

benefit for the life of the participant, based on a formula specified in the plan that accounts for

factors such as an employee’s salary history and years of service. In contrast, a defined

contribution plan is an employer-sponsored, account-based plan, such as a 401(k), that allows

individuals to accumulate tax-advantaged retirement savings in an individual account based on

employee or employer contributions and the investment returns (gains and losses) earned on the

account. The military retirement system includes both a defined benefit and a defined contribution

component. See GAO, Military Pensions: Servicemembers Need Better Information to Support

Retirement Savings Decisions, GAO-19-631 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 19, 2019).

19

A quasi-binomial logistic regression can be used to estimate the probability of an outcome when

there is too much variability in the data for a traditional probability model (e.g., logistic regression)

to produce accurate estimates.

20

We only discussed the 2021 DOD administrative data in our report because they were from the

same year as the 2021 survey data on the broader military spouse population that we analyzed.

21

We selected military spouses that had at least one child based, in part, on our background

interviews with military service organizations. Officials from these organizations noted that military

spouses with children are often limited in the hours they can work because they may face

challenges finding affordable child care or may be responsible for taking their children to and from

school, for example.

22

We sought to accommodate the schedules of all military spouses who applied to participate and

met our selection criteria. However, we could potentially be missing the perspectives of military

spouses who have less flexible work schedules if they chose not to apply to participate or did not

respond to our meeting invitation due to concerns about their availability.